Towards a Personalized Vestibular Assessment in Older Patients with Cochlear Implant

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Vestibular Evaluation

- •

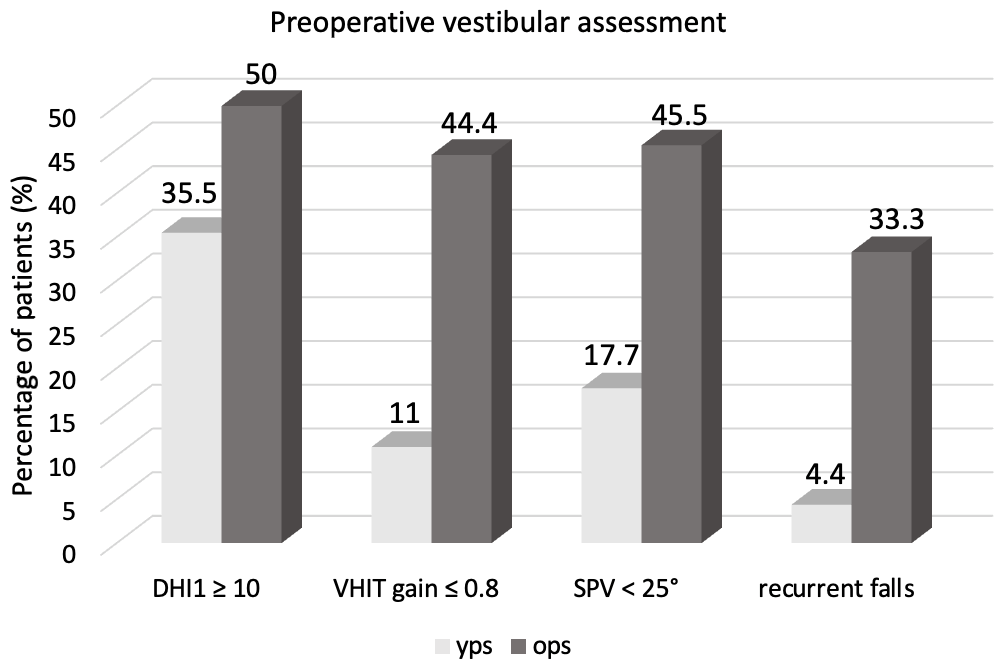

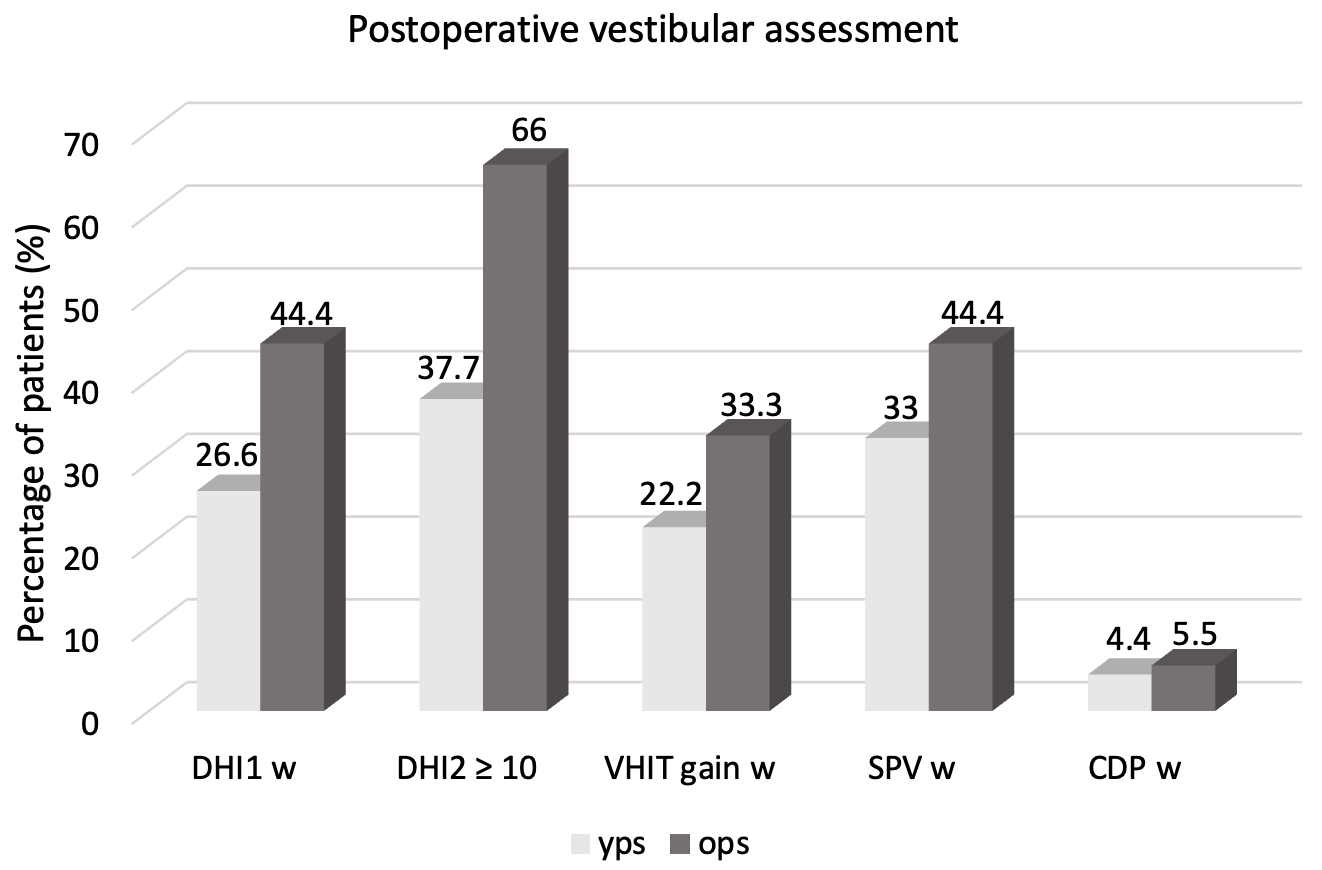

- The Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) (Italian version by Nola et al. [16]) was administered 24–48 h before surgery (DHI0), 24–48 h after surgery (DHI1), and one month after surgery (before CI activation) (DHI2) to evaluate the pre, peri, and postoperative dizziness, respectively [9,16]. It consists of 25 multiple choice questions (“yes”—4 points, “sometimes”—2 points, and “no”—0 points), which provide a total score from 0 (no handicaps) to 100 (the greatest ailment imaginable). Values are considered normal (<10), borderlines (10–16), mild (18–34), moderate (36–52), and severe (≥54).

- •

- Recurrent falls: Each patient was interviewed regarding the presence of recurrent falls in their daily life, providing a choice of 3 answers: “yes” (4 points), “sometimes” (2 points), and “no” (0 points).

- •

- Vestibular assessment was performed 24–48 h before surgery and one month after surgery (before CI activation), including:

- -

- Clinical examination to assess the presence of spontaneous and/or positional nystagmus and to perform the head-shaking test (HST) and clinical head impulse test (HIT).

- -

- Video head impulse test (VHIT) using a VOG device (ICS Impulse, GN Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark) to measure the gain of VOR (Vestibular–Oculomotor Reflex) for both the horizontal canals. It was performed with the patient sitting upright and fixating a visual target in front of him when the clinician generated head impulses by moving it abruptly and unpredictably in the horizontal plane. We considered normal VOR gain > 0.8 and normal gain asymmetry < 20% [9,17].

- -

- Bitermic caloric stimulation by the Fitzgerald–Hallpike technique (ICS Aircal Air Caloric Sprinkler Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark). It was performed in a conventional manner (air-flow of 0.8 L/min at temperatures of 50 °C and 24 °C for 60 s, in the dark, in supine position with the head raised at 30°). Nystagmus amplitude was calculated by the system as slow phase velocity (SPV) and measured in °/s. The Jongkee’s formula was used to quantify the asymmetry between the sides. Results were expressed as unilateral weakness (UW normal < 15%) and directional preponderance degree (DP normal < 15%). Bilateral hyporeflexia was defined by the sum of the maximal peak velocities of the slow phase caloric-induced nystagmus for stimulation with warm and cold water on each side (SPV) < 25°/s [9,18].

- -

- Computed Dynamic Posturography (CDP) (Equitest, Neurocom Int. Inc., Clackamas, OR, USA) was performed with the patient standing on a dual footplate enclosed by a visual surround in six balance conditions (eyes open/closed; visual surround steady/rotated; platform steady/rotated—Sensory Organization Test (SOT)) as previously described [19]. For each test, we considered the Composite Equilibrium Score (CES) showing the weighted average of the different conditions and Sensory Analysis (SA) showing the contribution of the different sensorial afferences (somatosensory, visual, vestibular, and visual-preference). We considered normal CES and SA to be >70 [9,19].

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, P.Z.; O’Malley, J.T.; de Gruttola, V.; Liberman, M.C. Age-Related Hearing Loss Is Dominated by Damage to Inner Ear Sensory Cells, Not the Cellular Battery That Powers Them. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 6357–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, S.; Kamenov, K.; Cieza, A. The world report on hearing, 2021. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 242–242A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, J.W.; Adams, J.K.; Wilkerson, B.J. The use of cochlear implantation in the elderly. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 27, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, S.S.; Goldstein, M.R.; Morris, S.A.; Jacob, A. Cochlear implant outcomes in the very elderly. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohloff, K.; Koopmann, M.; Wei, D.; Rudack, C.; Savvas, E. Cochlear Implantation in the Elderly: Does Age Matter? Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.J.; Moran, M.; O’Leary, S.J. Outcomes After Cochlear Implantation in the Very Elderly. Otol. Neurotol. 2016, 37, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovin, B.D.; Gorelik, D.; Lin, K.F.; Vrabec, J.T. Vestibular Hypofunction Screening in Older Cochlear Implant Candidates. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 171, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, F.C.; Petrus, L.; Martins, W.R.; Silva, I.M.C.; Lima, J.A.O.; Santos, N.M.D.S.; Turri-Silva, N.; Bahmad, F., Jr. The effect of cochlear implant surgery on vestibular function in adults: A meta-analysis study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 947589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picciotti, P.M.; Di Cesare, T.; Rodolico, D.; Di Nardo, W.; Galli, J. Clinical and Instrumental Evaluation of Vestibular Function Before and After Cochlear Implantation in Adults. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shen, T.; Cao, S.; Liu, Z.; Pang, W.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Presbycusis: Pathology, Signal Pathways, and Therapeutic Strategy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2410413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, M.J.; Batuecas, Á.; Cenjor, C.; Ferrán, S.; Gómez, J.R.; Lorenzo, A.I.; Marco, J.; Matiñó, E.; Morant, A.; Morera, C.; et al. Presbycusis and balance disorders in the elderly. Bibliographical review of ethiopathogenic aspects, consequences on quality of life and positive effects of its treatment. Acta Otorrinolaringol. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 74, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.R.; Akinsola, O.; Chaudhari, A.M.W.; Bigelow, K.E.; Merfeld, D.M. Measuring Vestibular Contributions to Age-Related Balance Impairment: A Review. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 635305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, K. The Aging Vestibular System: Dizziness and Imbalance in the Elderly. Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 82, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, Y.; Van de Berg, R.; Wuyts, F.; Walther, L.; Magnusson, M.; Oh, E.; Sharpe, M.; Strupp, M. Presbyvestibulopathy: Diagnostic criteria Consensus document of the classification committee of the Bárány Society. J. Vestib. Res. 2019, 29, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, S.; Yamasoba, T. Dizziness and Imbalance in the Elderly: Age-related Decline in the Vestibular System. Aging Dis. 2014, 6, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nola, G.; Mostardini, C.; Salvi, C.; Ercolani, A.P.; Ralli, G. Validity of Italian adaptation of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) and evaluation of the quality of life in patients with acute dizziness. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2010, 30, 190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Picciotti, P.M.; Rolesi, R.; Rossi, G.; Tizio, A.; Sergi, B.; Galli, J. Caloric Test, and Qualitative and Quantitative vHIT Analysis in Vestibular Schwannoma. Otol. Neurotol. 2025, 46, e215–e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, A.; Maihoub, S.; Tamás, L.; Szirmai, Á. A possible objective test to detect benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The 477 role of the caloric and video-head impulse tests in the diagnosis. J. Otol. 2022, 17, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picciotti, P.M.; Fiorita, A.; Di Nardo, W.; Quaranta, N.; Paludetti, G.; Maurizi, M. VEMPs and dynamic posturography after intra- 479 tympanic gentamycin in Menière’s disease. J. Vestib. Res. 2005, 15, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciotti, P.M.; Di Cesare, T.; Libonati, F.A.; Libonati, G.A.; Paludetti, G.; Galli, J. Presbycusis and pres-byvestibulopathy: Balance improvement after hearing loss restoration. Hear. Balance Commun. 2024, 22, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Y.; Merfeld, D.M.; Horak, F.B.; Redfern, M.S.; Manor, B.; Westlake, K.P.; Holstein, G.R.; Smith, P.F.; Bhatt, T.; Bohnen, N.I.; et al. Aging, Vestibular Function, and Balance: Proceedings of a National Institute on Aging/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Workshop. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhai, S. Aging and the peripheral vestibular system. J. Otol. 2018, 13, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayas, M.; Muzaffar, J.; Phillips, V.; Smith, M.E.; Borsetto, D.; Bance, M.L. Effect of Cochlear Implantation on Air Conduction and Bone Conduction Elicited Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials—A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaslin, D.L.; Jacobson, G.P.; Grantham, S.L.; Piker, E.G.; Verghese, S. The influence of unilateral saccular impairment on functional balance performance and self-report dizziness. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2011, 22, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Di Cesare, T.; Picciotti, P.M.; Di Nardo, W.; Rodolico, D.; Galli, J. Towards a Personalized Vestibular Assessment in Older Patients with Cochlear Implant. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020081

Di Cesare T, Picciotti PM, Di Nardo W, Rodolico D, Galli J. Towards a Personalized Vestibular Assessment in Older Patients with Cochlear Implant. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020081

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Cesare, Tiziana, Pasqualina Maria Picciotti, Walter Di Nardo, Daniela Rodolico, and Jacopo Galli. 2026. "Towards a Personalized Vestibular Assessment in Older Patients with Cochlear Implant" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020081

APA StyleDi Cesare, T., Picciotti, P. M., Di Nardo, W., Rodolico, D., & Galli, J. (2026). Towards a Personalized Vestibular Assessment in Older Patients with Cochlear Implant. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020081