Molecular-Guided Precision Oncology in Cancer of Unknown Primary: A State-of-the-Art Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Context and Evolution of CUP Management

2.1. Traditional Classification and Treatment Approaches

2.2. Early Molecular Approaches and Initial Setbacks

3. The Molecular Revolution in CUP Management

3.1. Landmark Clinical Trials

The Fudan CUP-001 Study

3.2. The CUPISCO Trial

3.3. Meta-Analysis of CUP Trials

3.4. Complementary Molecular Strategies

4. Molecular Diagnostic Technologies

4.1. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP)

4.2. Gene Expression Profiling (GEP)

4.3. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Methylation Classifiers

5. Tumor-Agnostic Therapeutic Landscape

5.1. FDA-Approved Tumor-Agnostic Therapies

5.2. Clinical Implementation Challenges

5.3. Research Challenges

6. Molecular Tumor Boards and Multidisciplinary Care

6.1. Role of Molecular Tumor Boards (MTBs)

6.2. Integration with Community Practice

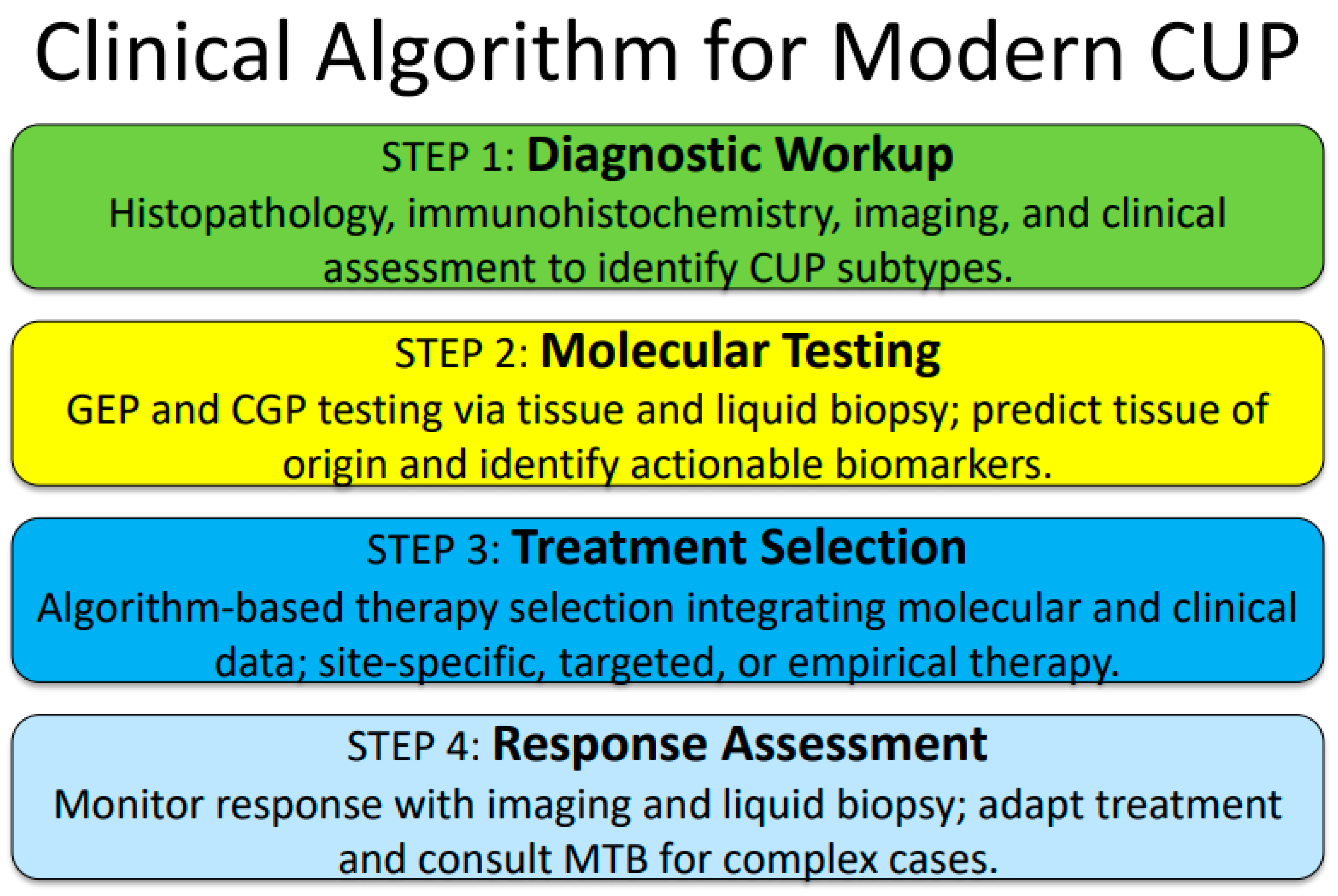

7. Clinical Algorithm for Modern CUP Management

Proposed Integrated Approach

8. Evidence Summary and Key Studies

8.1. Pivotal Clinical Trials Comparison

8.2. Biomarker Prevalence in CUP

9. Perspectives and Clinical Considerations

10. Implementation Challenges and Solutions

11. Future Directions and Research Priorities

11.1. Technological Advances

11.2. Clinical Research and Care Delivery Priorities

12. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pentheroudakis, G.; Golfinopoulos, V.; Pavlidis, N. Switching benchmarks in cancer of unknown primary: From autopsy to microarray. Eur. J. Cancer 2007, 43, 2026–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, A.C. Key Statistics for Cancers of Unknown Primary. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/cancer-unknown-primary/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Greco, F.A. Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: A New Era of Practice-Changing Approaches to Diagnosis, Staging, and Precision Therapy. JCO Oncol. Adv. 2024, 1, e2400041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.S.; Wang, K.; Gay, L.; Otto, G.A.; White, E.; Iwanik, K.; Palmer, G.; Yelensky, R.; Lipson, D.M.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Site: New Routes to Targeted Therapies. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Krishnamurthy, N.; Banks, K.C.; De, P.; Williams, K.; Williams, C.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Lippman, S.M.; Lanman, R.B.; Kurzrock, R. Utility of Genomic Analysis In Circulating Tumor DNA from Patients with Carcinoma of Unknown Primary. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Bochtler, T.; Pauli, C.; Baciarello, G.; Delorme, S.; Hemminki, K.; Mileshkin, L.; Moch, H.; Oien, K.; Olivier, T.; et al. Cancer of unknown primary: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up ☆. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Bochtler, T.; Pauli, C.; Shiu, K.-K.; Cook, N.; de Menezes, J.J.; Pazo-Cid, R.A.; Losa, F.; Robbrecht, D.G.J.; Tomášek, J.; et al. Molecularly guided therapy versus chemotherapy after disease control in unfavourable cancer of unknown primary (CUPISCO): An open-label, randomised, phase 2 study. Lancet 2024, 404, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, S.; Mo, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Hu, S.; Yang, H.; Hou, Y.; et al. Site-specific therapy guided by a 90-gene expression assay versus empirical chemotherapy in patients with cancer of unknown primary (Fudan CUP-001): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyiourou, M.; Bochtler, T.; Pauli, C.; Moch, H.; Brobeil, A.; Pantel, K.; Stenzinger, A.; Krämer, A. Rethinking cancer of unknown primary: From diagnostic challenge to targeted treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgewater, J.; van Laar, R.; Floore, A.; Van’T Veer, L. Gene expression profiling may improve diagnosis in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizazi, K.; Maillard, A.; Penel, N.; Baciarello, G.; Allouache, D.; Daugaard, G.; Van de Wouw, A.; Soler, G.; Vauleon, E.; Chaigneau, L.; et al. A phase III trial of empiric chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine or systemic treatment tailored by molecular gene expression analysis in patients with carcinomas of an unknown primary (CUP) site (GEFCAPI 04). Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Kurata, T.; Takiguchi, Y.; Arai, M.; Takeda, K.; Akiyoshi, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Onoe, T.; Mukai, H.; Matsubara, N.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial Comparing Site-Specific Treatment Based on Gene Expression Profiling with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Patients with Cancer of Unknown Primary Site. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaki, C.; Eid, M.; Bakouny, Z.; Hobeika, C.; Chehade, R.E.H.; Chebel, R.; Boussios, S.; Anthony Greco, F.; Pavlidis, N.; Rassy, E. Molecularly directed therapy in cancers of unknown primary: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 222, 115447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony Greco, F. Cancer of unknown primary site and TNM staging: A new paradigm for patient management. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, C.; Bochtler, T.; Mileshkin, L.; Baciarello, G.; Losa, F.; Ross, J.S.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Zarkavelis, G.; Yalcin, S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; et al. A Challenging Task: Identifying Patients with Cancer of Unknown Primary (CUP) According to ESMO Guidelines: The CUPISCO Trial Experience. Oncol. 2021, 26, e769–e779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q.; Yao, Q.; Feng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lai, Q.; Zhang, G.; et al. Clinical validation of a 90-gene expression test for tumor tissue of origin diagnosis: A large-scale multicenter study of 1417 patients. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiri, E.; Mueller, W.C.; Rosenwald, S.; Zepeniuk, M.; Klinke, E.; Edmonston, T.B.; Werner, M.; Lass, U.; Barshack, I.; Feinmesser, M.; et al. A Second-Generation MicroRNA-Based Assay for Diagnosing Tumor Tissue Origin. Oncol. 2012, 17, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.S.; Sokol, E.S.; Moch, H.; Mileshkin, L.; Baciarello, G.; Losa, F.; Beringer, A.; Thomas, M.; Elvin, J.A.; Ngo, N.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Origin: Retrospective Molecular Classification Considering the CUPISCO Study Design. Oncol. 2020, 26, e394–e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentheroudakis, G.; Pavlidis, N.; Fountzilas, G.; Krikelis, D.; Goussia, A.; Stoyianni, A.; Sanden, M.; St Cyr, B.; Yerushalmi, N.; Benjamin, H.; et al. Novel microRNA-based assay demonstrates 92% agreement with diagnosis based on clinicopathologic and management data in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.; Martínez-Cardús, A.; Sayols, S.; Musulén, E.; Balañá, C.; Estival-Gonzalez, A.; Moutinho, C.; Heyn, H.; Diaz-Lagares, A.; de Moura, M.C.; et al. Epigenetic profiling to classify cancer of unknown primary: A multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasan, H.S.; Wang, J.; Elaine McCartney, E.M.; Soifer, H.; Treuner, K.; Zhang, Y.; Schnabel, C.; Carty, K.; McMahon, L.; Evans, T.R.J.; et al. LBA100 CUP-ONE trial: A prospective double-blind validation of molecular classifiers in the diagnosis of cancer of unknown primary and clinical outcomes. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, S1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Arora, A.; Capanu, M.; Camacho, N.; Won, H.H.; Zehir, A.; Gao, J.; Chakravarty, D.; Schultz, N.; Klimstra, D.S.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with cancer of unknown primary in the modern era. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 3015–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Rassy, E.; Khaled, H.; Pavlidis, N. Liquid biopsy: A new diagnostic, predictive and prognostic window in cancers of unknown primary. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 105, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbiah, V.; Gouda, M.A.; Ryll, B.; Burris, H.A., III; Kurzrock, R. The evolving landscape of tissue-agnostic therapies in precision oncology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphalen, C.B.; Martins-Branco, D.; Beal, J.R.; Cardone, C.; Coleman, N.; Schram, A.M.; Halabi, S.; Michiels, S.; Yap, C.; André, F.; et al. The ESMO Tumour-Agnostic Classifier and Screener (ETAC-S): A tool for assessing tumour-agnostic potential of molecularly guided therapies and for steering drug development. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 936–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, M.A.; Janku, F.; Wahida, A.; Buschhorn, L.; Schneeweiss, A.; Abdel Karim, N.; De Miguel Perez, D.; Del Re, M.; Russo, A.; Curigliano, G.; et al. Liquid Biopsy Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (LB-RECIST). Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlander, M.G.; Ma, X.-J.; Kesty, N.C.; Bao, L.; Salunga, R.; Schnabel, C.A. Performance and Clinical Evaluation of the 92-Gene Real-Time PCR Assay for Tumor Classification. J. Mol. Diagn. 2011, 13, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadhachary, G.R.; Talantov, D.; Raber, M.N.; Meng, C.; Hess, K.R.; Jatkoe, T.; Lenzi, R.; Spigel, D.R.; Wang, Y.; Greco, F.A.; et al. Molecular Profiling of Carcinoma of Unknown Primary and Correlation with Clinical Evaluation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4442–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Jiang, J.; Du, B.; Wan, M.; Ma, X.; Chen, X.; Lin, L.; et al. New techniques to identify the tissue of origin for cancer of unknown primary in the era of precision medicine: Progress and challenges. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handorf, C.R. Gene Expression Analysis and Immunohistochemistry in Evaluation of Cancer of Unknown Primary: Time for a Patient-Centered Approach. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2011, 9, 1415–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Zhao, M.; Shady, M.; Lipkova, J.; Mahmood, F. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature 2021, 594, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurgeon, L.; Mitchell, C.; Cook, N.; Conway, A.-M. Cancer of unknown primary: The hunt for its elusive tissue-of-origin—Is it time to call off the search? Br. J. Cancer 2025, 133, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorkowski, S.W.; Dermawan, J.K.; Rubin, B.P. The practical utility of AI-assisted molecular profiling in the diagnosis and management of cancer of unknown primary: An updated review. Virchows Arch. 2024, 484, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Heimberger, A.B.; Marshall, J.; Heath, E.; Drabick, J.; Helmstetter, A.; Xiu, J.; Magee, D.; Stafford, P.; Nabhan, C.; et al. Machine learning analysis using 77,044 genomic and transcriptomic profiles to accurately predict tumor type. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, A.-M.; Pearce, S.P.; Clipson, A.; Hill, S.M.; Chemi, F.; Slane-Tan, D.; Ferdous, S.; Hossain, A.S.M.M.; Kamieniecka, K.; White, D.J.; et al. A cfDNA methylation-based tissue-of-origin classifier for cancers of unknown primary. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, J.; Conway, P.J.; Subramani, B.; Meyyappan, D.; Russell, S.; Mahadevan, D. Using cfDNA and ctDNA as Oncologic Markers: A Path to Clinical Validation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, V. Tissue-agnostic cancer therapies: Promise, reality, and the path forward. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledge, G.W.; Yoshino, T.; Xiu, J.; Helmstetter, A.; Ribeiro, J.R.; Klimov, S.; Gilg, B.; Gao, J.J.; Elton, J.; Oberley, M.J.; et al. Real-world evidence provides clinical insights into tissue-agnostic therapeutic approvals. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, M.A.; Subbiah, V. Tissue-Agnostic Cancer Therapy Approvals. Surg. Oncol. Clin. 2024, 33, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, T.A.; Yarchoan, M.; Jaffee, E.; Swanton, C.; Quezada, S.A.; Stenzinger, A.; Peters, S. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: Utility for the oncology clinic. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanale, D.; Corsini, L.R.; Pedone, E.; Randazzo, U.; Fiorino, A.; Di Piazza, M.; Brando, C.; Magrin, L.; Contino, S.; Piraino, P.; et al. Potential agnostic role of BRCA alterations in patients with several solid tumors: One for all, all for one? Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 190, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaun, G.; Borchert, S.; Metzenmacher, M.; Lueong, S.; Wiesweg, M.; Zaun, Y.; Pogorzelski, M.; Behrens, F.; Schildhaus, H.-U.; Virchow, I.; et al. Comprehensive biomarker diagnostics of unfavorable cancer of unknown primary to identify patients eligible for precision medical therapies. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 200, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, H.; Takiguchi, Y.; Minami, H.; Akiyoshi, K.; Segawa, Y.; Ueda, H.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kondoh, C.; Matsumoto, K.; Takahashi, S.; et al. Site-Specific and Targeted Therapy Based on Molecular Profiling by Next-Generation Sequencing for Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: A Nonrandomized Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, L.; Heinrich, K.; Zhang, D.; Dorman, K.; Rühlmann, K.; Hasselmann, K.; Klauschen, F.; Kumbrink, J.; Jung, A.; Rudelius, M.; et al. Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) through the lens of precision oncology: A single institution perspective. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 8225–8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphalen, C.B.; Boscolo Bielo, L.; Aftimos, P.; Beltran, H.; Benary, M.; Chakravarty, D.; Collienne, M.; Dienstmann, R.; El Helali, A.; Gainor, J.; et al. ESMO Precision Oncology Working Group recommendations on the structure and quality indicators for molecular tumour boards in clinical practice. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, J.K.; Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Jones, M.; Gakkhar, S.; Ma, Y.; Moore, R.; Mungall, A.J.; Zhao, Y.; Taylor, M.D.; Gelmon, K.; et al. Application of a Neural Network Whole Transcriptome–Based Pan-Cancer Method for Diagnosis of Primary and Metastatic Cancers. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamidipati, D.; Subbiah, V. Impact of tissue-agnostic approvals for patients with gastrointestinal malignancies. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamidipati, D.; Subbiah, V. Tumor-agnostic drug development in dMMR/MSI-H solid tumors. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.A.; Nelson, B.E.; Buschhorn, L.; Wahida, A.; Subbiah, V. Tumor-Agnostic Precision Medicine from the AACR GENIE Database: Clinical Implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2753–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, V.; Burris, H.A., III; Kurzrock, R. Revolutionizing cancer drug development: Harnessing the potential of basket trials. Cancer 2024, 130, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehnholz, S.P.; Nissan, M.H.; Zhang, H.; Kundra, R.; Nandakumar, S.; Lu, C.; Carrero, S.; Dhaneshwar, A.; Fernandez, N.; Xu, B.W.; et al. Quantifying the Expanding Landscape of Clinical Actionability for Patients with Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Thawani, R. Tumor-Agnostic Therapies in Practice: Challenges, Innovations, and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Design | Population | Molecular Strategy | Primary Endpoint | Key Results | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fudan CUP-001 Liu et al. 2024 [8] | Phase III RCT N = 182 | Unfavorable CUP First-line setting | 90-gene GEP Site-specific therapy | Progression-free survival | PFS (9.6 vs. 6.6 months) hazard ratio of 0.68 (95% CI 0.50–0.94; p = 0.017). | Practice-changing NCCN/ ESMO impact |

| CUPISCO Kramer et al. 2024 [7] | Phase II RCT N = 573 | Non-squamous unfavorable CUP Post-chemotherapy | CGP-based Tumor-agnostic therapy | Progression-free Survival | HR 0.72 (95% CI 0.56–0.92; p = 0.0079) | Tumor-agnostic validation Precision oncology |

| Hayashi et al. JCO 2019 [12] | Phase II RCT N = 150 | CUP patients Treatment-naive | Microarray, GEP-guided Site-specific therapy | Overall Survival | HR 0.79 (95% CI 0.54–1.16) p = 0.23 | Negative study Limited targeted options |

| GEFCAPI 04 Fizazi et al. 2019 [11] | Phase III RCT N = 150 | Unfavorable CUP First-line setting | 92-gene GEP Molecular profiling Tailored therapy | Overall Survival | HR 0.87 (95% CI 0.57–1.33) p = 0.52 | Negative study Pre-precision era |

| Meta-Analysis Labaki et al. 2025 [13] | Systematic Review N = 1644 | 6 prospective studies 4 RCTs included | Various molecular approaches Pooled analysis | Overall Survival | Favors molecular therapy, Statistical significance | Confirmatory evidence Practice validation |

| Platform Type | Technology | Sample Type | Key Features | Accuracy | Clinical Utility | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling (GEP) | 90-and 92-gene assays RT-PCR/NGS | FFPE tissue Fresh tissue |

| 80–90% sensitivity 85–95% specificity | Site-specific therapy guidance Treatment selection |

|

| Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) | 300+ gene NGS WES/WGS | Tissue biopsy Liquid biopsy |

| 95%+ analytical accuracy Variable actionability | Tumor-agnostic therapy Clinical trial matching |

|

| cfDNA Methylation | CUPiD classifier Methylation arrays | Plasma/serum Blood-based |

| High tissue specificity Good sensitivity | Serial monitoring Minimal invasive diagnosis |

|

| Multi-omics Integration | AI/ML algorithms Combined platforms | Multi-modal Tissue + liquid |

| Potentially superior Under development | Future precision medicine Comprehensive profiling |

|

| Agent(s) | Target/Biomarker | Mechanism | Prevalence in CUP | Approval Status | Key Efficacy Data | Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab | MSI-H/dMMR TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) | PD-1 inhibitor Immune checkpoint | 2–4% MSI-H 8–12% TMB-H | FDA-Ap | ORR 29–57% Durable responses OS benefit |

|

| Larotrectinib Entrectinib Repotrectinib | NTRK gene fusions TRK A/B/C | TRK inhibitor ATP-competitive | <1% prevalence | FDA-Ap | ORR 75–80% Tumor-agnostic efficacy CNS activity |

|

| Selpercatinib | RET alterations Fusions/mutations | Selective RET inhibitor Multi-kinase activity | 1–2% prevalence | FDA-Ap | ORR 60–85% CNS penetration Durable responses |

|

| Dabrafenib + Trametinib | BRAF V600E V600K mutations | BRAF + MEK inhibition MAPK pathway | 2–5% prevalence | FDA-Ap | ORR 46% 6-month PFS 46% Multiple histologies |

|

| Trastuzumab Deruxtecan | HER2 overexpression IHC 3+/ISH+ | ADC technology Topoisomerase I inhibitor | 5–10% prevalence | FDA-ap | ORR 37–54% Multiple solid tumors Low HER2 activity |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Subbiah, V.; Rassy, E.; Greco, F.A. Molecular-Guided Precision Oncology in Cancer of Unknown Primary: A State-of-the-Art Perspective. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020080

Subbiah V, Rassy E, Greco FA. Molecular-Guided Precision Oncology in Cancer of Unknown Primary: A State-of-the-Art Perspective. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020080

Chicago/Turabian StyleSubbiah, Vivek, Elie Rassy, and Frank A. Greco. 2026. "Molecular-Guided Precision Oncology in Cancer of Unknown Primary: A State-of-the-Art Perspective" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020080

APA StyleSubbiah, V., Rassy, E., & Greco, F. A. (2026). Molecular-Guided Precision Oncology in Cancer of Unknown Primary: A State-of-the-Art Perspective. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020080