Randomized Personalized Trial for Stress Management Compared to Standard of Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants, Recruitment and Consent

2.3. Baseline Period

2.4. Intervention Period

2.4.1. Stress Management Techniques

2.4.2. Randomization

2.4.3. Intervention

2.4.4. Participant Report

2.4.5. Post-Intervention Observation Period

2.5. Primary Outcome

2.6. Secondary Outcomes

2.7. Analysis

2.7.1. Sample Size Calculation

2.7.2. Primary Analysis

2.7.3. Secondary Analyses

3. Results

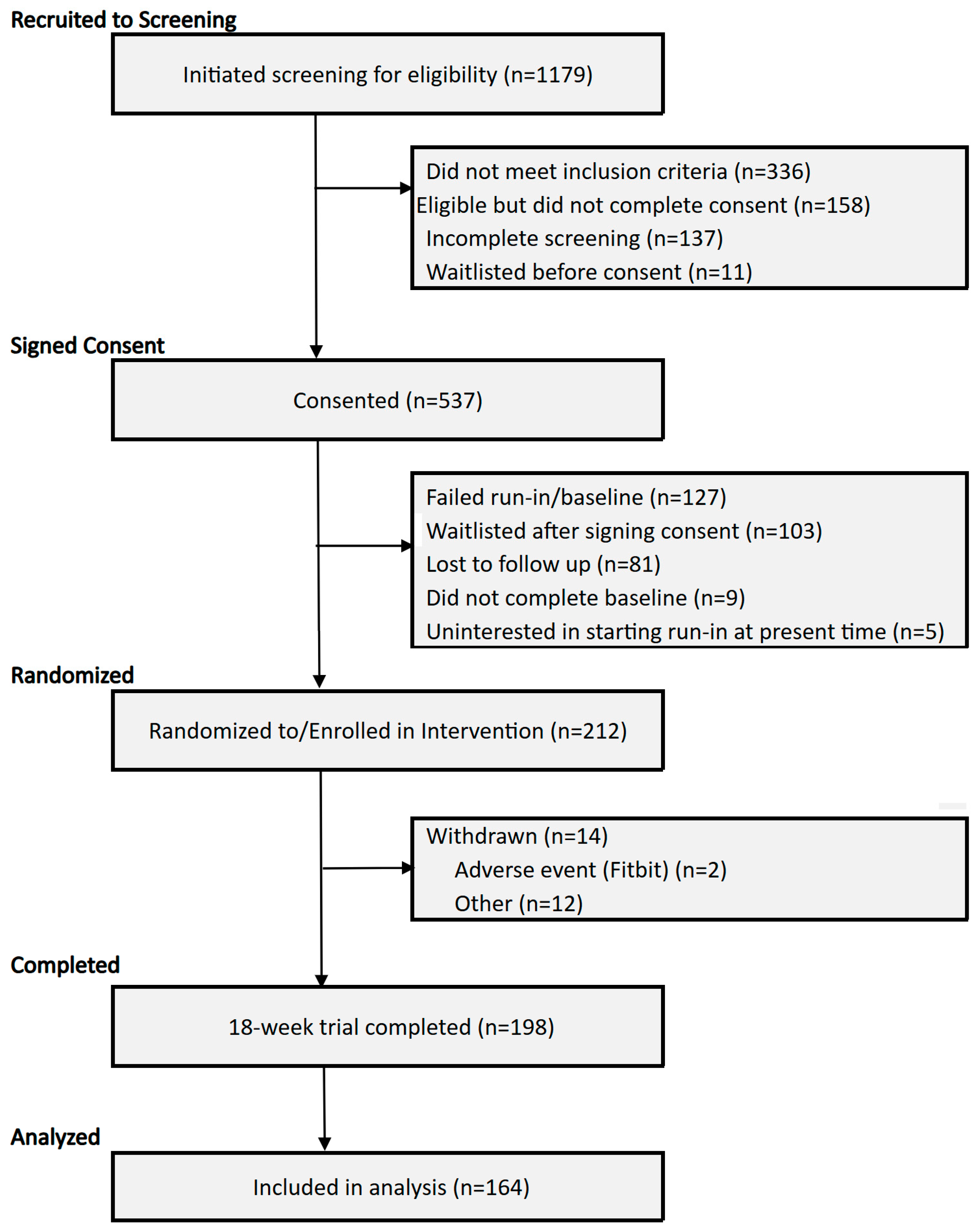

3.1. Enrollment and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Perceived Stress and EMA Measures

3.3. Stress Management Interventions

3.4. Recommendation for Stress Management

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis—Comparison of Self-Report Measures by Compliance with Personalized Trial Recommendations

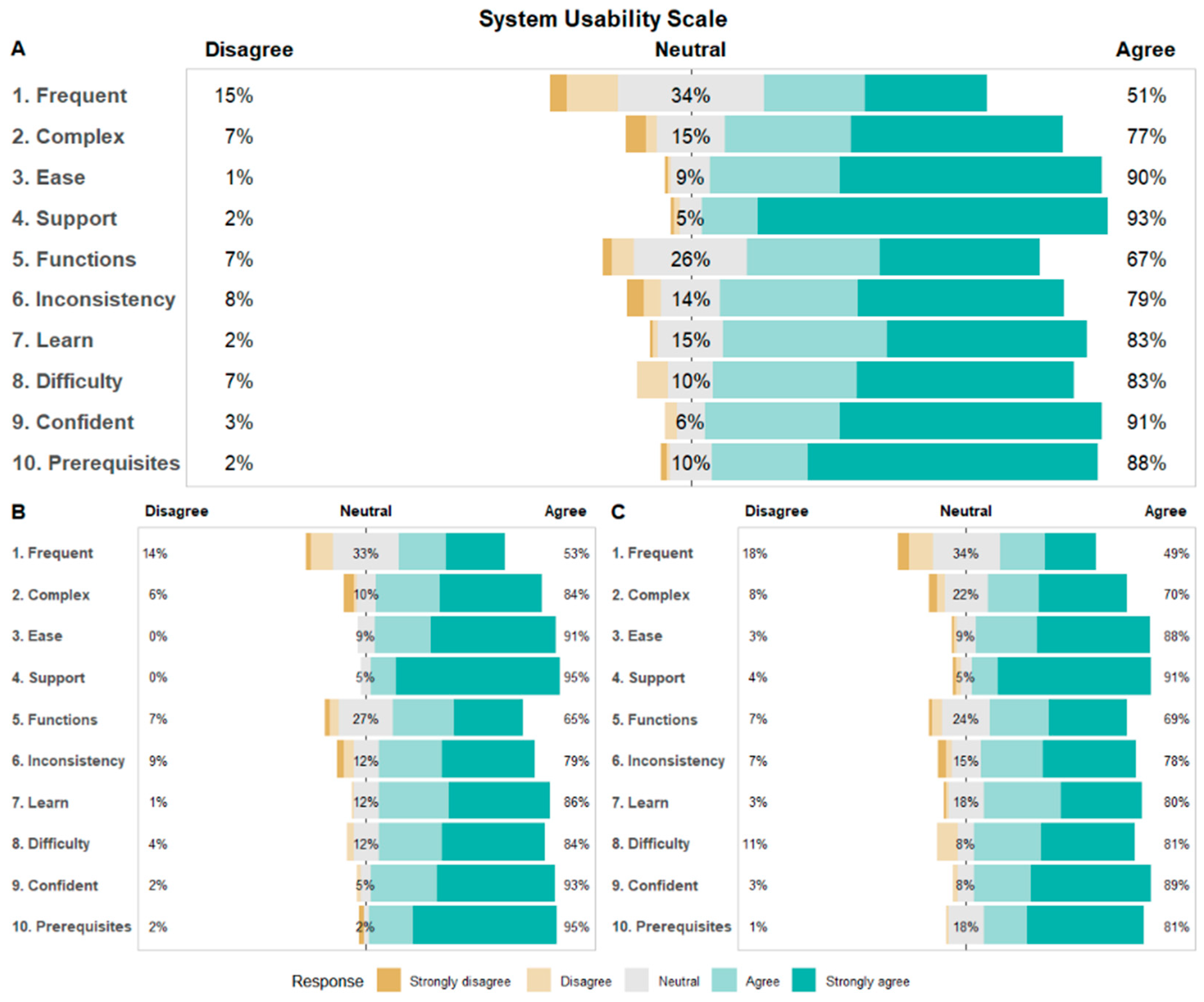

3.6. System Usability Scale (SUS) and Participant Satisfaction

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMA | Ecological Momentary Assessments |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| GLMM | Generalized Linear Mixed Models |

| mHealth | Mobile Health |

References

- Association, A.P. Stress in America: Stress and current events. In Stress in America™ Survey; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale, J.E. Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, G.N. Psychological stress and heart disease: Fact or folklore? Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarino, V.; Bremner, J.D. Stress and cardiovascular disease: An update. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Cui, R. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Dimsdale, J.E. The effect of psychosocial stress on sleep: A review of polysomnographic evidence. Behav. Sleep Med. 2007, 5, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick, J.D.; Horn, R.S.; Quick, J.C. Health consequences of stress. In Job Stress; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, S.; Sibinga, E.M.; Gould, N.F.; Rowland-Seymour, A.; Sharma, R.; Berger, Z.; Sleicher, D.; Maron, D.D.; Shihab, H.M. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Thompson, D.R.; Ski, C.F. Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 86, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehli, I.; Burns, R.D.; Bai, Y.; Ziegenfuss, D.H.; Block, M.E.; Brusseau, T.A. Mind–body physical activity interventions and stress-related physiological markers in educational settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Norman, D.; Schmid, C.; Sim, I.; Kravitz, R.L. Personalized data science and personalized (N-of-1) trials: Promising paradigms for individualized health care. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L.H.; Dallery, J. The family of single-case experimental designs. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, R.L.; Duan, N. Conduct and implementation of personalized trials in research and practice. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, K.; Cheung, K.; Friel, C.; Suls, J. Introducing data sciences to N-of-1 designs, statistics, use-cases, the future, and the moniker ‘N-of-1’ Trial. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selker, H.P.; Dulko, D.; Greenblatt, D.J.; Palm, M.; Trinquart, L. The use of N-of-1 trials to generate real-world evidence for optimal treatment of individuals and populations. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 7, e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrett, E.; Williamson, E.; Brack, K.; Beaumont, D.; Perkins, A.; Thayne, A.; Shakur-Still, H.; Roberts, I.; Prowse, D.; Goldacre, B. Statin treatment and muscle symptoms: Series of randomised, placebo controlled n-of-1 trials. BMJ 2021, 372, n135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, T.R.; Monjed, A.; Zou, G.Y.; Hegele, R.A.; McDonald, C.G.; Mahon, J.L. N-of-1 (single-patient) trials for statin-related myalgia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, J.P.; Wootton, S.H.; Holder, T.; Molony, D. A scoping review of randomized trials assessing the impact of n-of-1 trials on clinical outcomes. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohart, A.; O’hara, M.; Leitner, L.; Wertz, F.; Stern, E.; Schneider, K.; Greening, T. Recommended principles and practices for the provision of humanistic psychosocial services: Alternative to mandated practice and treatment guidelines. Retrieved Novemb. 2003, 1, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gabler, N.B.; Duan, N.; Vohra, S.; Kravitz, R.L. N-of-1 trials in the medical literature: A systematic review. Med. Care 2011, 49, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A.M.; Miller, D.; D’Angelo, S.; Perrin, A.; Wiener, R.; Greene, B.; Romain, A.-M.N.; Arader, L.; Chandereng, T.; Kuen Cheung, Y. Protocol for randomized personalized trial for stress management compared to standard of care. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1233884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Watt, I.S. Patient involvement in treatment decision-making: The case for a broader conceptual framework. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 63, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L.; Mor, M.K.; Haas, G.L.; Gordon, A.J.; Cashy, J.P.; Schaefer, J.H., Jr.; Hausmann, L.R. The role of primary care experiences in obtaining treatment for depression. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.; Leonhart, R.; Wills, C.E.; Simon, D.; Härter, M. The impact of patient participation on adherence and clinical outcome in primary care of depression. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 65, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, S.; Medvedev, O.N. Perceived stress scale (PSS). In Handbook of Assessment in Mindfulness Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1849–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, L.; Liu, Y.; Dallery, J. Ecological momentary assessment: A systematic review of validity research. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2022, 45, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, M.L.; Kubiak, T. Ecological momentary assessment in behavioral medicine. In The Handbook of Behavioral Medicine; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 429–446. [Google Scholar]

- Mengelkoch, S.; Moriarity, D.P.; Novak, A.M.; Snyder, M.P.; Slavich, G.M.; Lev-Ari, S. Using ecological momentary assessments to study how daily fluctuations in psychological states impact stress, well-being, and health. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, A.M.; Chiuzan, C.; Friel, C.P.; Miller, D.; Rodillas, J.; Duer-Hefele, J.; Cheung, Y.K.; Davidson, K.W. Protocol for a personalized (N-of-1) trial for testing the effects of a mind–body intervention on sleep duration in middle-aged women working in health care. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2024, 41, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S.; Ryu, G.W.; Choi, M. Methodological strategies for ecological momentary assessment to evaluate mood and stress in adult patients using mobile phones: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.P.; Turner, J.A.; Romano, J.M.; Fisher, L.D. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain 1999, 83, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; D’Angelo, S.; Ahn, H.; Chandereng, T.; Miller, D.; Perrin, A.; Romain, A.-M.N.; Scatoni, A.; Friel, C.P.; Cheung, Y.-K. A Series of Personalized Virtual Light Therapy Interventions for Fatigue: Feasibility Randomized Crossover Trial for N-of-1 Treatment. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e45510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.J.; D’Angelo, S.; Kaplan, M.; Tashnim, Z.; Miller, D.; Ahn, H.; Falzon, L.; Dominello, A.J.; Foroughi, C.; Chandereng, T.; et al. A Series of Virtual Interventions for Chronic Lower Back Pain: A Feasibility Pilot Study for a Series of Personalized (N-of-1) Trials. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.J.; Chandereng, T.; Ahn, H.; Slotnick, S.; Miller, D.; Perrin, A.; Rodillas, J.; Friel, C.P.; Goodwin, A.M.; Cheung, Y.K. A Series of Personalized Melatonin Supplement Interventions for Poor Sleep: Feasibility Randomized Crossover Trial for Personalized N-of-1 Treatment. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e58192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A retrospective. J. Usability Stud. 2013, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.R. The system usability scale: Past, present, and future. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schork, N.J. Accommodating serial correlation and sequential design elements in personalized studies and aggregated personalized studies. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 2022, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidou, I.; Aristeidis, L.; Lambrinos, L. A gamified app for supporting undergraduate students’ mental health: A feasibility and usability study. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221109059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Khan, S.R.; Islam, N.N.; Rezwan-A-Rownok, M.; Zaman, S.R.; Zaman, S.R. A mobile application for mental health care during COVID-19 pandemic: Development and usability evaluation with system usability scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Information System, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam, 25–27 January 2021; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beukering, M.; Velu, A.; Van Den Berg, L.; Kok, M.; Mol, B.W.; Frings-Dresen, M.; De Leeuw, R.; Van Der Post, J.; Peute, L. Usability and usefulness of a mobile health app for pregnancy-related work advice: Mixed-methods approach. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, E.; Suh, J.; Bin Morshed, M.; McDuff, D.; Rowan, K.; Hernandez, J.; Abdin, M.I.; Ramos, G.; Tran, T.; Czerwinski, M.P. Design of digital workplace stress-reduction intervention systems: Effects of intervention type and timing. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Oh, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Baik, S. Smart stress care: Usability, feasibility and preliminary efficacy of fully automated stress management application for employees. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G. N of 1 randomized trials: A commentary. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 76, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, P.B.; Bittlinger, M.; Kimmelman, J. Individualized therapy trials: Navigating patient care, research goals and ethics. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravitz, R.L.; Duan, N.; Niedzinski, E.J.; Hay, M.C.; Subramanian, S.K.; Weisner, T.S. What Ever Happened to N-of-1 Trials? Insiders’ Perspectives and a Look to the Future. Milbank Q. 2008, 86, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, D.; Quake, S.R.; McCabe, E.R.; Chng, W.J.; Chow, E.K.; Ding, X.; Gelb, B.D.; Ginsburg, G.S.; Hassenstab, J.; Ho, C.-M. Enabling technologies for personalized and precision medicine. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, R.L.; Schmid, C.H.; Marois, M.; Wilsey, B.; Ward, D.; Hays, R.D.; Duan, N.; Wang, Y.; MacDonald, S.; Jerant, A. Effect of mobile device–supported single-patient multi-crossover trials on treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawksworth, O.; Chatters, R.; Julious, S.; Cook, A.; Biggs, K.; Solaiman, K.; Quah, M.C.; Cheong, S.C. A methodological review of randomised n-of-1 trials. Trials 2024, 25, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Jaeschke, R.; McGinn, T.; Rennie, D.; Meade, M.; Cook, D. N-of-1 randomized controlled trials: Study design. In Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature; American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Keller, J.L.; Jaeschke, R.; Rosenbloom, D.; Adachi, J.D.; Newhouse, M.T. The n-of-1 randomized controlled trial: Clinical usefulness: Our three-year experience. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 112, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, E.B. N-of-1 trials: A new future? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikles, C.J.; Yelland, M.; Glasziou, P.P.; Del Mar, C. Do individualized medication effectiveness tests (n-of-1 trials) change clinical decisions about which drugs to use for osteoarthritis and chronic pain? Am. J. Ther. 2005, 12, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewning, B.; Bylund, C.L.; Shah, B.; Arora, N.K.; Gueguen, J.A.; Makoul, G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, L.; McGraw, S. Participation in medical decision making: The patients’ perspective. Med. Decis. Mak. 2007, 27, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swar, B.; Hameed, T.; Reychav, I. Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golman, R.; Hagmann, D.; Loewenstein, G. Information avoidance. J. Econ. Lit. 2017, 55, 96–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, M.L.; Bylund, C.L.; Chewning, B.; Makoul, G. The impact of patient participation in health decisions within medical encounters: A systematic review. Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 36, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Ahn, H.; Miller, D.; Monane, R.; Butler, M.J. Personalized Feedback for Personalized Trials: Construction of Summary Reports for Participants in a Series of Personalized Trials for Chronic Lower Back Pain. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 10–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, F.; Lazarus, R.S. Active coping processes, coping dispositions, and recovery from surgery. Biopsychosoc. Sci. Med. 1973, 35, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, M.; Dutton, S.; Imel, Z.E.; Hill, P.L. Real-world stress and control: Integrating ambulatory physiological and ecological momentary assessment technologies to explain daily wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1438422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kershaw, K.N. Feasibility of using ecological momentary assessment and continuous heart rate monitoring to measure stress reactivity in natural settings. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.M.; Mendes, W.B. A large-scale study of stress, emotions, and blood pressure in daily life using a digital platform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105573118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total Sample | Personalized Arm 1 a (N = 53) | Personalized Arm 2 b (N = 53) | Standard-of-Care Arm 3 (N = 106) | p Value c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.1 (12.4) | 42.1 (12.2) | 40.0 (12.9) | 41.1 (12.3) | 0.686 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.608 | |||||

| Female | 154 (72.6%) | 39 (73.5%) | 42 (79.2%) | 73 (68.9%) | ||

| Male | 57 (26.9%) | 14 (26.4%) | 11 (20.8%) | 32 (30.2%) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Race, n (%) | 0.314 | |||||

| Asian | 31 (14.6%) | 7 (13.2%) | 7 (13.2%) | 17 (16.0%) | ||

| Black | 29 (13.7%) | 9 (17.0%) | 5 (9.4%) | 15 (14.2%) | ||

| Mixed | 8 (3.8%) | 1 (1.9%) | 5 (9.4%) | 2 (1.9%) | ||

| Other | 19 (9.0%) | 4 (7.5%) | 4 (7.5%) | 11 (10.4%) | ||

| White | 122 (57.5%) | 30 (56.6%) | 31 (58.5%) | 61 (57.5%) | ||

| Declined/Unknown | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.468 | |||||

| Hispanic | 36 (17.0%) | 6 (11.3%) | 12 (22.6%) | 18 (17.0%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 174 (82.1%) | 47 (88.7%) | 40 (75.5%) | 87 (82.1%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Score, mean (SD) | 25.0 (3.9) | 24.4 (3.5) | 25.7 (3.7) | 25.0 (4.1) | 0.986 | |

| Baseline EMA Stress, mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.7) | 4.3 (2.0) | 4.3 (1.6) | 4.0 (1.6) | 0.101 | |

| Outcome | Change Between Follow-Up and Baseline Periods; Mean (SD) | Welch’s Two-Sample t-Test p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personalized (Arms 1 and 2); N = 84 | Standard-of-Care (Arm 3); N = 80 | ||

| EMA Stress | −0.50 (1.8) | −0.31 (1.7) | 0.496 |

| Weekly Stress * | −0.12 (0.3) | −0.14 (0.3) | 0.780 |

| EMA Pain | −0.09 (1.6) | 0.10 (1.2) | 0.397 |

| EMA Fatigue | −0.73 (1.8) | −0.68 (1.7) | 0.878 |

| EMA Mood | 0.58 (1.4) | 0.54 (1.3) | 0.856 |

| EMA Confidence | 0.35 (1.3) | 0.68 (1.3) | 0.100 |

| EMA Concentration | 0.26 (1.5) | 0.48 (1.4) | 0.346 |

| Selected Intervention | Personalized Trials; N(%) | Standard of Care; N(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 (N = 42) | Arm 2 (N = 39) | Arm 3 (N = 73) | |

| Mindfulness meditation | 9 (21.4%) | 14 (35.9%) | 23 (31.5%) |

| Yoga | 10 (23.8%) | 8 (20.5%) | 13 (17.81%) |

| Brisk walking | 23 (54.8%) | 17 (43.6%) | 37 (50.7%) |

| Recommended Intervention | |||

| Mindfulness meditation | 18 (42.9%) | 10 (25.6%) | N/A |

| Yoga | 6 (14.3%) | 14 (35.9%) | |

| Brisk walking | 18 (42.9%) | 15 (38.5%) | |

| Selected Intervention | Recommended Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness Meditation (N = 28) | Yoga (N = 20) | Brisk Walking (N = 33) | |

| Mindfulness meditation (N = 23) | 12 (42.9%) | 4 (20.0%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Yoga (N = 18) | 5 (17.9%) | 8 (40.0%) | 5 (15.1%) |

| Brisk walking (N = 40) | 11 (39.3%) | 8 (40.0%) | 21 (63.6%) |

| Outcome | Standard-of-Care | Personalized Trial Non-Complier | p-Value | Personalized Trial Complier | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMA Stress | REF | 0.08 (0.035) | 0.825 | −0.66 (0.34) | 0.049 |

| Weekly Stress | REF | −0.02 (0.07) | 0.787 | −0.04 (0.07) | 0.546 |

| EMA Pain | REF | −0.19 (0.29) | 0.505 | −0.20 (0.28) | 0.466 |

| EMA Fatigue | REF | 0.13 (0.35) | 0.714 | −0.24 (0.34) | 0.481 |

| EMA Mood | REF | 0.03 (0.28) | 0.928 | 0.14 (0.27) | 0.594 |

| EMA Confidence | REF | −0.31 (0.26) | 0.238 | −0.15 (0.25) | 0.568 |

| EMA Concentration | REF | −0.37 (0.29) | 0.206 | 0.02 (0.28) | 0.929 |

| Measure | Values, n (%) | All Participants (N = 155) | Personalized Trial Arm (N = 81) | Standard-of-Care Arm (N = 74) | p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD; Range) | Mean (SD; Range) | Mean (SD; Range) | |||

| System Usability Scale overall score | 155 (73) | 81.31 (13.97; 25–100) | 82.69 (13.01; 40–100) | 79.8 (14.88; 25–100) | 0.20 |

| System Usability Scale individual items b | |||||

| 1. I think that I would like to use this system frequently. | 155 (73) | 2.59 (1.13; 0–4) | 2.67 (1.1; 0–4) | 2.51 (1.16; 0–4) | 0.40 |

| 2. I did not find the system unnecessarily complex. c | 155 (73) | 3.14 (1.07; 0–4) | 3.25 (1.03; 0–4) | 3.03 (1.1; 0–4) | 0.20 |

| 3. I thought the system was easy to use. | 155 (73) | 3.48 (0.74; 0–4) | 3.54 (0.65; 2–4) | 3.41 (0.83; 0–4) | 0.25 |

| 4. I do not think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this system. c | 155 (73) | 3.70 (0.69; 0–4) | 3.78 (0.52; 2–4) | 3.62 (0.82; 0–4) | 0.17 |

| 5. I found the various functions in this system were well integrated. | 155 (73) | 2.95 (1.01; 0–4) | 2.9 (1.02; 0–4) | 3 (0.99; 0–4) | 0.54 |

| 6. I did not think there was too much inconsistency in this system. c | 155 (73) | 3.14 (1.05; 0–4) | 3.14 (1.06; 0–4) | 3.15 (1.04; 0–4) | 0.94 |

| 7. I would imagine that most people would learn to use this system very quickly. | 155 (73) | 3.26 (0.81; 0–4) | 3.36 (0.75; 1–4) | 3.16 (0.86; 0–4) | 0.13 |

| 8. I did not find the system very awkward to use. c | 155 (73) | 3.25 (0.91; 1–4) | 3.32 (0.83; 1–4) | 3.18 (0.98; 1–4) | 0.33 |

| 9. I felt very confident using the system. | 155 (73) | 3.48 (0.73; 1–4) | 3.49 (0.71; 1–4) | 3.47 (0.76; 1–4) | 0.86 |

| 10. I did not need to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this system. c | 155 (73) | 3.52 (0.80; 0–4) | 3.63 (0.77; 0–4) | 3.39 (0.82; 1–4) | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Goodwin, A.M.; Chandereng, T.; Ahn, H.; Miller, D.; Slotnick, S.; Perrin, A.; Cheung, Y.K.; Davidson, K.W.; Butler, M.J. Randomized Personalized Trial for Stress Management Compared to Standard of Care. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010023

Goodwin AM, Chandereng T, Ahn H, Miller D, Slotnick S, Perrin A, Cheung YK, Davidson KW, Butler MJ. Randomized Personalized Trial for Stress Management Compared to Standard of Care. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoodwin, Ashley M., Thevaa Chandereng, Heejoon Ahn, Danielle Miller, Stefani Slotnick, Alexandra Perrin, Ying Kuen Cheung, Karina W. Davidson, and Mark J. Butler. 2026. "Randomized Personalized Trial for Stress Management Compared to Standard of Care" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010023

APA StyleGoodwin, A. M., Chandereng, T., Ahn, H., Miller, D., Slotnick, S., Perrin, A., Cheung, Y. K., Davidson, K. W., & Butler, M. J. (2026). Randomized Personalized Trial for Stress Management Compared to Standard of Care. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010023