GDM-Related Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders in the Mothers and Their Progeny, and the Underlying Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Women with GDM

| Study Design | Sample Size (GDM vs. non-GDM) | Diagnostic Criteria | Main Effects Odd Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Outcome Assessment | Timing of Outcome Assessment | Influencing Factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A prospective cohort study | 229 vs. 1220 | WHO criteria | Depression scores ↑ at both 1-month and 3-month postpartum | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | 1-month and 3-month postpartum | Higher glucose levels during pregnancy | [10] |

| A pilot study | 382 vs. 366 | WHO criteria | Rate of depression ↑ during pregnancy | Montogomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale | During pregnancy | [19] | |

| A prospective cohort study | 105 vs. 108 | International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group criteria (IADPSG) | Depression scores and rate of developing depression ↑ during pregnancy; No association at 2 and 4 weeks after delivery | EPDS | After the second trimester At 2 and 4 weeks after delivery | [14] | |

| A longitudinal observational study | 795 (early 474 + late 321) vs. 1346 | IADPSG | Prevalence of depression/anxiety ↑ in early GDM than late GDM and control; Early GDM was significantly associated with depression 1.84 (1.37–2.47) and anxiety 1.36 (1.03–1.79) | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | Early GDM was detected in the first trimester, and late GDM during 24–28 gestational weeks (GW) | Diagnostic time | [34] |

| A longitudinal study | 77 vs. 103 | IADPSG | The incidence of depression symptoms in the 2nd trimester ↑; The incidence of depression and anxiety symptomatology -- from 2nd to 3rd trimester | Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | During pregnancy | Glycemic control Gestational weeks | [35] |

| A prospective longitudinal observational pilot study | 35 (15 insulin treatment + 20 diet management) vs. 20 | IADPSG | Depression score -- among three groups; Anxiety score ↑ in GDM-insulin group vs. control; Stress -- between GDM-insulin and GDM-diet groups | Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDS); STAI | During 24–34 GW At > 36 GW | GDM management (insulin vs. diet) | [25] |

| A population-based cohort study | 12,140 vs. 314,583 | International Classification of Diseases, version 9/10 (ICD-9, ICD-10) | Prevalence of depression -- Prevalence of anxiety -- | During pregnancy and the first year postpartum | [27] | ||

| A cross-sectional analysis | 425 vs. 1747 | ICD-9 | Depression scores -- | PHQ-9 | Postpartum | [20] | |

| A prospective cohort study | 150 vs. 916 | Finnish Gestational Diabetes Study | Risk of developing depression ↑ 1.70 (1.00–2.89) | EPDS | During third trimester of pregnancy 8 weeks after delivery | BMI in the first trimester Maternal age at delivery | [12] |

| A retrospective cohort study | 29,200 vs. 29,200 | Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines | Risk of depression ↑ during pregnancy 1.82 (1.28–2.59); No significant difference in the first year postpartum; An 8% increased risk of depression beyond first year postpartum | During 24 weeks gestation up to delivery; In the first year postpartum; Beyond 1 year postpartum | Time of outcome assessment | [18] | |

| A prospective longitudinal study | 50 vs. 50 | Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society criteria | Anxiety score ↑ in the third trimester Anxiety score -- before delivery and at 6 weeks postpartum | STAI | At the beginning of the third trimester; Antepartum; 6 weeks postpartum | Time of outcome assessment | [26] |

| A cross sectional case control study | 30 vs. 30 | IADPSG | Cognitive functions ↓ | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) Trail Making Test | During 32–36 GW | [30] | |

| A prospective cohort study | 1292 vs. 204,171 | ICD-10 | Risk of dementia ↑ 1.67 (1.03–2.69) | ICD-10 | At 38–73 years of age | Physical activity | [32] |

| Multivariable Mendelian Randomization | Finnish Gestational Diabetes Study | No significant causal relationship between GDM and maternal Alzheimer’s disease or dementia | [33] |

3.2. Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders in GDM Progeny

3.2.1. Abnormal Neurodevelopment in Fetuses and Neonates

3.2.2. Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring

3.3. Neuropsychiatric Disorders in GDM Offspring

3.4. Influencing Factors

| Reference | Country | GDM Diagnostic Criteria | Study Design | Sample Size (GDM vs. non-GDM) | Age of Children | Outcomes Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Influencing Factors | Covariate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | Sweden | Clinical diagnosis | Registry cohort | 21,325 vs. 2,326,033 | 6–29 years | Risk of ID, ASD, and ADHD ↑ the strongest associations with ID during 27–30 GW | Time of diagnosis | child sex, birth year, parental education/income/immigration/psychiatric history, birthplace, maternal age, parity, smoking, PCOS and pre-pregnancy BMI |

| [99] | USA | Clinical diagnosis | Retrospective cohort | 1417 vs. 13,063 | 1.0–6.3 years | non-Hispanic White: Risk of learning disorder, ASD, ID, and speech/language disorders ↑ other races/ethnicities: Risk of neurodevelopmental disorders -- | Races | maternal age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, prepregnancy BMI, smoking during pregnancy, preexisting chronic conditions, mental health status, substance use, polycystic ovarian syndrome, birth year, and offspring sex |

| [66] | Norway | WHO1999 | Prospective cohort | 72 vs. 194 | 7 years | Neurodevelopment disorders (motor skills, executive functions, perception, memory, language, social skills and possible emotional/behavioral problems)-- | birthweight, child sex, age at follow-up, and maternal socioeconomic status | |

| [59] | Multinational | Clinical diagnosis | Meta-analysis | 1–39 years | Risk of ID -- | parental age, SES, smoking, BMI, HDP, birth weight, gestational age, and parental psychiatric disorders | ||

| [84] | Spain | Carpenter-Coustan | Prospective cohort | 68 vs. 169 | 0.5 & 1.5 years | Language score ↓ Motor skills and Cognition -- | Obesity Dietary management | maternal age, education, employment status, marital status, pre-pregnancy smoking status, primiparity, child’s sex, pre-pregnancy BMI (except when it was the independent variable), gestational weeks at delivery, and intervention groups |

| [89] | India | Carpenter-Coustan | Prospective cohort | 32 vs. 483 | 9.7 years | Learning/language scores ↑ | child’s age, sex, gestation, neonatal weight and head circumference, as well as maternal age, parity, BMI, parents’ socioeconomic status, education level, and rural/urban residence | |

| [56] | Denmark | WHO1999 | Registry cohort | 4286 vs. 501,045 | 15–16 years | Academic performance ↓ | Birth weight | maternal age, parity, conception mode, hypertensive disorders, delivery mode, smoking, nationality, residence, cohabitation, education, offspring sex, birth weight, gestational age/weight cerebral palsy |

| [67] | Japan | IADPSG | Prospective cohort | 2161 vs. 79,543 | 0.5–4 years | Male: Neurodevelopmental delays (problem-solving ability, fine motor skills, and personal and social skills)↓ Female: Neurodevelopmental delays -- | Gender | child’s sex, maternal primiparity, breastfeeding at 6 months, low birth weight, maternal education level, and maternal smoking during pregnancy |

| [82] | India | IADPSG | Cross-sectional | 52 vs. 52 | 3.5 months | Motor skills ↓ Mental developmental score ↓ | GDM management | maternal age, pre-pregnancy weight, infant weight, length, head circumference, and their Z-scores |

| [83] | Israel | Clinical diagnosis | Prospective cohort | 32 vs. 57 | 5–12 years | Motor skill ↓ Attention deficits ↑ Cognition -- | Antidiabetic medications Maternal glycemia control | age, birth order, socioeconomic status, gestational age, and parental education level |

| [68] | Sweden | ACOG | Registry cohort | 25,035 vs. 290,792 | 6–29 years | Diagnosed at 26 GW or earlier: Risk of ASD ↑1.63 (1.35–1.97) Diagnosed after 26 GW: Risk of ASD -- 0.98 (0.84–1.15) | Time of diagnosis Gestational age at birth | maternal age, parity, education, household income, race/ethnicity, history of comorbidity, child sex, and—in a subgroup—prepregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and smoking during pregnancy. |

| [70] | USA | Clinical diagnosis | Registry cohort | 2544 vs. 36,266 | 0–8 years | Risk of ASD ↑ GDM only: 1.30 (0.80–2.09) Obesity and GDM: 2.53 (1.72–3.73) | Obesity | maternal age at birth, prepregnancy BMI, maternal race, and year of the child’s birth |

| [71] | China | self-report | Case-control | 67 vs. 554 | Mean 4 years | Male: Risk of ASD ↑ 3.67 (1.16–11.65) Female: Risk of ASD -- | Gender | child sex, gestational age, mode of delivery, parity, maternal education level, and further included prenatal multivitamin use, folic acid intake in the first three months of pregnancy, and assisted reproduction |

| [65] | Canada | Clinical diagnosis | Prospective cohort | 221 vs. 2612 | 1.5–7 years | Language score ↓ | Education | maternal prepregnancy BMI, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, age, residence, education, monthly income, parity, smoking history, fetal sex, birth weight, delivery mode, and gestational age |

| [101] | USA | Carpenter-Coustan | Retrospective cohort | 29,534 vs. 295,304 | ≥4 years (median 4.9) | Requiring medication: Risk of ADHD ↑ 1.26 (1.14–1.41) Not requiring medication: Risk of ADHD -- 0.93 (0.86–1.01) | Antidiabetic medications | maternal age at delivery, parity, education, race/ethnicity, household income, maternal history of ADHD, maternal history of comorbidity (cancer or heart, lung, kidney, liver diseases), birth year, and child sex |

| [76] | Multinational | Clinical diagnosis | Meta-analysis | 515 vs. 984,499 | 4 years–adolescence | Risk of ADHD ↑1.64 (1.25–5.56) | Birth weight | |

| [79] | China | IADPSG | Prospective cohort | 419 vs. 2841 | 1.5 & 3 years | Risk of autistic traits ↑ 1.49 (1.11–2.00) ADHD symptoms-- | pre-pregnancy BMI, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, maternal age, place of residence, educational level, average monthly income, parity, smoking history, fetal sex, birth weight, delivery mode, and gestational age at birth | |

| [73] | Finland | Clinical diagnosis | Registry cohort | 101,696 vs. 543,347 | ≤11 years | Risk of ASD and ADHD -- | birth year, sex, perinatal problems, number of fetuses, mode of delivery, maternal age, parity, marital status, country of birth, smoking history, maternal psychiatric disorders, and systemic inflammatory diseases | |

| [58] | China | Carpenter-Coustan | Registry cohort | 90,200 vs. 777,946 | 7–12 years | Risk of ASD, ADHD, and development delay ↑ Cerebral palsy and epilepsy -- | Birth weight | parental age, birth year, child sex, family income, urbanization level, maternal hypertensive disorders, and preterm delivery. |

| [75] | USA | Clinical diagnosis | Prospective cohort | 216 vs. 2163 | Mean 4.1 years | Female: Risk of ASD -- Male: Risk of ASD ↑ 3.26 (1.58–6.41) | Maternal depression | maternal race, ethnicity, age at delivery, pre-pregnancy BMI category, child-assigned sex at birth, gestational age category, and age at CBCL assessment. |

| [100] | USA | Carpenter-Coustan | Retrospective cohort | 42,420 vs. 389,854 | 5–25 years | Requiring medications: Risk of depression and anxiety ↑ Not requiring medications: Risk of depression and anxiety -- | Antidiabetic medications | maternal age at delivery, parity, education level, race/ethnicity, household income, maternal history of psychiatric disorders, pre-pregnancy medical comorbidity, smoking during pregnancy, pre-pregnancy body mass index, birth year, and child sex |

| [96] | Canada | Clinical diagnosis | Registry cohort | 81,325 vs. 1,989,148 | 0–16 years | Risk of cerebral palsy -- | maternal age, parity, socioeconomic characteristics (income, drug benefit receipt, residence), infant’s sex, birth year, pregestational hypertension, gestational hypertensive disorders, start of prenatal care, and congenital malformations |

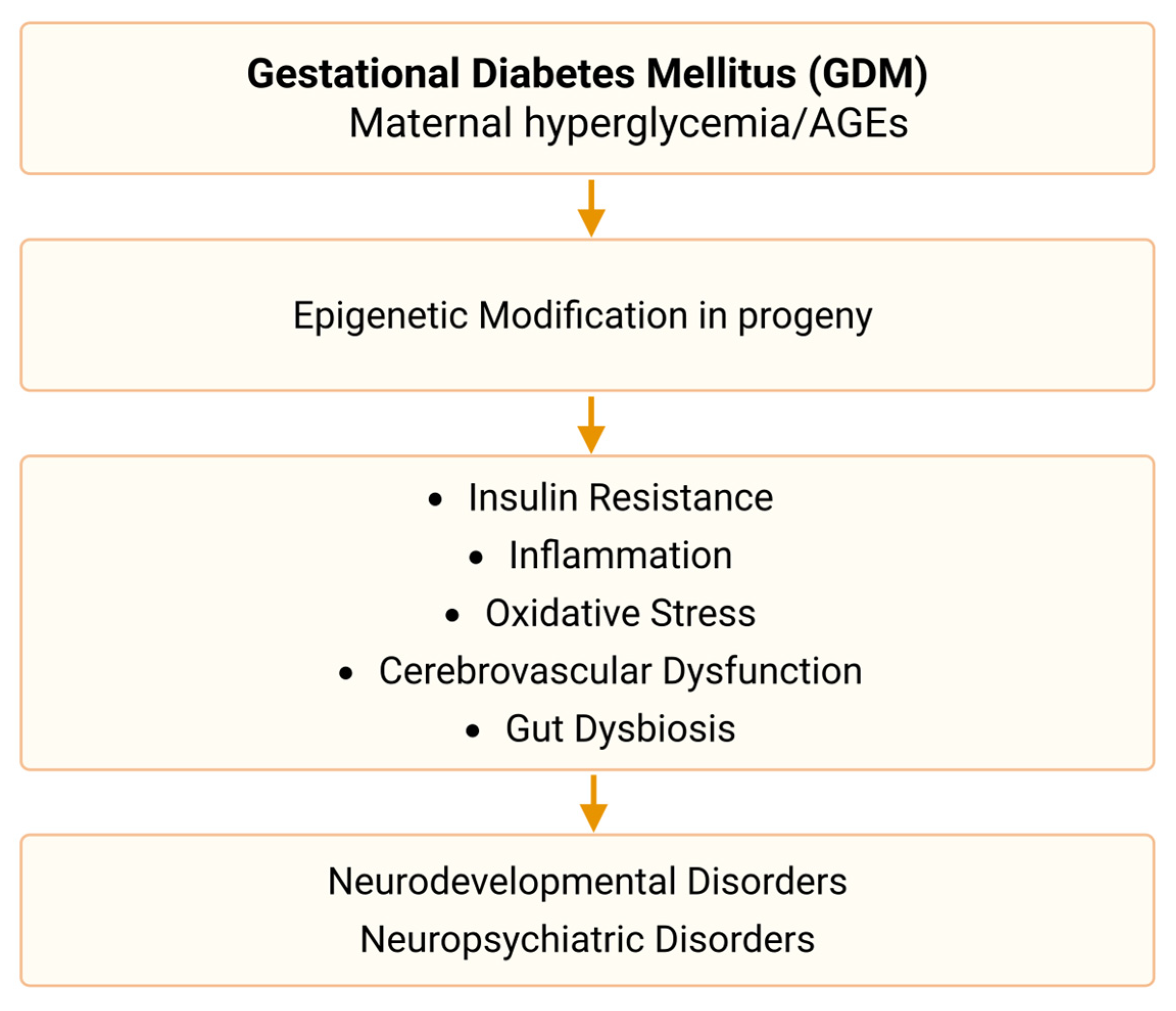

3.5. Mechanisms

3.6. Intervention

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moon, J.H.; Jang, H.C. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Diagnostic Approaches and Maternal-Offspring Complications. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautzky-Willer, A.; Winhofer, Y.; Kiss, H.; Falcone, V.; Berger, A.; Lechleitner, M.; Weitgasser, R.; Harreiter, J. Gestational diabetes mellitus (Update 2023). Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2023, 135, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, B.E.; Gabbe, S.G.; Persson, B.; Lowe, L.P.; Dyer, A.R.; Oats, J.J.; Buchanan, T.A. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovitz, Z.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Haddad, L. Fetal Brain Development: Regulating Processes and Related Malformations. Life 2022, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhaye, J.; Knoblich, J.A. Brain organoids: An ensemble of bioassays to investigate human neurodevelopment and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaso, A.; Adams, J.; Peng, W.; Sibbritt, D. The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health 2021, 18, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H. Protecting the mental health of women in the perinatal period. Lancet Psychiatr. 2015, 2, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, S.; Salve, H.R.; Goswami, K.; Sagar, R.; Kant, S. Burden of common mental disorders among pregnant women: A systematic review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2018, 36, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafa, A.; Dong, J.Y. Gestational diabetes and risk of postpartum depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, J.K.L.; Lee, A.H.; Pham, N.M.; Tang, L.; Pan, X.F.; Binns, C.W.; Sun, X. Gestational diabetes and postnatal depressive symptoms: A prospective cohort study in Western China. Women Birth 2019, 32, e427–e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OuYang, H.; Chen, B.; Abdulrahman, A.M.; Li, L.; Wu, N. Associations between Gestational Diabetes and Anxiety or Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 9959779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruohomaki, A.; Toffol, E.; Upadhyaya, S.; Keski-Nisula, L.; Pekkanen, J.; Lampi, J.; Voutilainen, S.; Tuomainen, T.; Heinonen, S.; Kumpulainen, K.; et al. The association between gestational diabetes mellitus and postpartum depressive symptomatology: A prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Spyropoulou, A.C.; Kalogerakis, Z.; Vousoura, E.; Moraitou, M.; Zervas, I.M. Association between gestational diabetes and perinatal depressive symptoms: Evidence from a Greek cohort study. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2017, 18, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Endo, M.; Ohashi, K. Depression and diet-related distress among Japanese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Nurs. Health Sci. 2023, 25, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, A.M.; Dunne, F.P.; Lydon, K.; Conneely, S.; Sarma, K.; McGuire, B.E. Diabetes in pregnancy: Worse medical outcomes in type 1 diabetes but worse psychological outcomes in gestational diabetes. QJM Int. J. Med. 2017, 110, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dame, P.; Cherubini, K.; Goveia, P.; Pena, G.; Galliano, L.; Facanha, C.; Nunes, M.A. Depressive Symptoms in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The LINDA-Brazil Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 7341893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, H.; Ye, W.; Lyu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Li, R.; Xu, Y. Effect of Gestational Diabetes on Postpartum Depression-like Behavior in Rats and Its Mechanism. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, R.; Rahme, E.; Da Costa, D.; Dasgupta, K. Association between gestational diabetes mellitus and depression in parents: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 1827–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasha, K.; Hussain, A.; Khan, A.K. Prevalence of depression among subjects with and without gestational diabetes mellitus in Bangladesh: A hospital based study. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2015, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, J.G.; Russo, J.; Gavin, A.R.; Melville, J.L.; Katon, W.J. Diabetes and depression in pregnancy: Is there an association? J. Women’s Health 2011, 20, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, X.; Qiang, W.; Lu, M.; Jiang, M.; Hou, Y.; Gu, Y.; Tao, F.; Zhu, B. A longitudinal cohort study of gestational diabetes mellitus and perinatal depression. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinberg, K.; Yisaschar-Mekuzas, Y. Assessing Mental Health Conditions in Women with Gestational Diabetes Compared to Healthy Pregnant Women. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Yan, X.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Wei, S.; Chen, J.; Wu, F.; Chen, J.; Zhao, M.; Luo, C. A correlation analysis on the postpartum anxiety disorder and influencing factors in puerperae with gestational diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1202884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, A.L.; Sevenhuysen, G.; Harvey, D.; Salamon, E. Stress and anxiety in women with gestational diabetes during dietary management. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.E.; Ogden, K.J.; Radford, A.; Ingram, E.R.; Campbell, J.E.; Dennis, A.; Corbould, A.M. Exploring the psychological wellbeing of women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): Increased risk of anxiety in women requiring insulin. A Prospective Longitudinal Observational Pilot Study. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2023, 11, 2170378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniells, S.; Grenyer, B.F.; Davis, W.S.; Coleman, K.J.; Burgess, J.A.; Moses, R.G. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Is a diagnosis associated with an increase in maternal anxiety and stress in the short and intermediate term? Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beka, Q.; Bowker, S.; Savu, A.; Kingston, D.; Johnson, J.A.; Kaul, P. Development of Perinatal Mental Illness in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, 350–355.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, F.E.; Ozyazar, M.; Pala, A.S.; Elmali, A.D.; Yilmaz, B.; Uygunoglu, U.; Bozluolcay, M.; Tuten, A.; Bingol, A.; Hatipoglu, E. Evaluation of cognitive functions in gestational diabetes mellitus. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2015, 123, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, S.; Deng, X.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Li, E. Cognitive Dysfunction of Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Perinatal Period. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 2302379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Yerrabelli, D.; Sagili, H.; Sahoo, J.P.; Gaur, G.S.; Kumar, A. Relationship between advanced glycated end products and maternal cognition in gestational diabetes: A case control study. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 7806–7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Contreras, D.C.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Lawn, R.B.; Mitsunami, M.; Purdue-Smithe, A.C.; Zhang, C.; Oken, E.; Chavarro, J.E. Lifetime history of gestational diabetes and cognitive function in parous women in midlife. Diabetologia 2025, 68, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, D.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, F.; Xie, W. Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with greater incidence of dementia during long-term post-partum follow-up. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 295, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; Liu, J.; Chan, K.H.K. Evaluating the Causal Effects of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, Heart Disease, and High Body Mass Index on Maternal Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: Multivariable Mendelian Randomization. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 833734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemavathy, S.; Deepa, M.; Uma, R.; Gowri, R.; Pradeepa, R.; Hannah, W.; Shivashri, C.; Subashini, R.; Mohaneswari, D.; Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie, Y.; et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus in South Asia. Prim. Care Diabetes 2025, 19, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, A.; Fekonja, U.; Pongrac Barlovic, D. Prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in women with gestational diabetes: A longitudinal cohort study. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutic, M.; Matijas, M.; Stefulj, J.; Brekalo, M.; Nakic Rados, S. Gestational diabetes mellitus and peripartum depression: A longitudinal study of a bidirectional relationship. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, M.C.; Mappa, I.; Pietrolucci, M.E.; Lu, J.L.A.; Antonio, F.D.; Rizzo, G. Fetal brain development in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Perinat. Med. 2024, 52, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, A.; Sever, B. Changes in fetal intracranial anatomy during maternal pregestational and gestational diabetes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleroglu, F.Y.; Ocal, A.; Bakirci, I.T.; Cetin, A. Does diabetes mellitus affect the development of fetal brain structures and spaces including corpus callosum, subarachnoid space, insula, and parieto-occipital fissure? J. Clin. Ultrasound 2023, 51, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, K.; Schleger, F.; Kiefer-Schmidt, I.; Fritsche, L.; Kummel, S.; Bocker, M.; Heni, M.; Weiss, M.; Haring, H.-U.; Preissl, H.; et al. Gestational Diabetes Impairs Human Fetal Postprandial Brain Activity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 4029–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, R.; Tanacan, A.; Serbetci, H.; Agaoglu, Z.; Haksever, M.; Ozkavak, O.O.; Karagoz, B.; Kara, O.; Sahin, D. The impact of gestational diabetes on the development of fetal frontal lobe: A case-control study from a tertiary center. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2024, 52, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabani Zanjani, M.; Nasirzadeh, R.; Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Yoonesi Asl, L.; Alemzadeh, S.A.; Askari, S. Fetal cerebral hemodynamic in gestational diabetic versus normal pregnancies: A Doppler velocimetry of middle cerebral and umbilical arteries. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2014, 114, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Xue, L.; Yu, M.; Deng, Z.; Lei, X.; Chen, G. Abnormal neonatal brain microstructure in gestational diabetes mellitus revealed by MRI texture analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappler, M.; Volleritsch, N.; Hammerl, M.; Pellkofer, Y.; Griesmaier, E.; Gizewski, E.R.; Kaser, S.; Kiechl-Kohlendorfer, U.; Neubauer, V. Microstructural Brain Development and Neurodevelopmental Outcome of Very Preterm Infants of Mothers with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Neonatology 2023, 120, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.C.; Xing, Q.N.; Shang, H.L.; Zhu, P.Y.; Zhang, X.A. Brain Development in Infants of Mothers with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2020, 44, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.M.; Alves, J.M.; Chow, T.; Clark, K.A.; Luo, S.; Toga, A.W.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A. Selective morphological and volumetric alterations in the hippocampus of children exposed in utero to gestational diabetes mellitus. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021, 42, 2583–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Hsu, E.; Lawrence, K.E.; Adise, S.; Pickering, T.A.; Herting, M.M.; Buchanan, T.; Page, K.A.; Thompson, P.M. Associations among prenatal exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus, brain structure, and child adiposity markers. Obesity 2023, 31, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, J.M.; Garrett, A.J.; Schneider, L.A.; Hodyl, N.A.; Goldsworthy, M.R.; Coat, S.; Rowan, J.A.; Hague, W.M.; Pitcher, J.B. Reduced Cortical Excitability, Neuroplasticity, and Salivary Cortisol in 11–13-Year-Old Children Born to Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. EBioMedicine 2018, 31, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Semeia, L.; Veit, R.; Luo, S.; Angelo, B.C.; Chow, T.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Preissl, H.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A.; et al. Exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus in utero impacts hippocampal functional connectivity in response to food cues in children. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.A.; Luo, S.; Wang, X.; Chow, T.; Alves, J.; Buchanan, T.A.; Xiang, A.H. Children Exposed to Maternal Obesity or Gestational Diabetes Mellitus During Early Fetal Development Have Hypothalamic Alterations That Predict Future Weight Gain. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Angelo, B.C.; Chow, T.; Monterosso, J.R.; Thompson, P.M.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A. Associations Between Exposure to Gestational Diabetes Mellitus In Utero and Daily Energy Intake, Brain Responses to Food Cues, and Adiposity in Children. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.L.B.; Sauder, K.A.; Tregellas, J.R.; Legget, K.T.; Gravitz, S.L.; Ringham, B.M.; Glueck, D.H.; Johnson, S.L.; Dabelea, D. Exposure to maternal diabetes in utero and offspring eating behavior: The EPOCH study. Appetite 2017, 116, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Gao, P.; Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Lin, Z.; Huang, F.; Zhu, L.; Lu, Y.; et al. Neonatal Circulating Amino Acids and Lipid Metabolites Mediate the Association of Maternal Gestational Diabetes Mellitus with Offspring Neurodevelopment at 1 Year. Nutrients 2025, 17, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Luo, C.; Zhou, J.; Liang, X.; Wen, J.; Huang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Association between maternal diabetes and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 202 observational studies comprising 56.1 million pregnancies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, S.; Dalman, C.; Karlsson, H.; Gardner, R. Association of maternal diabetes with neurodevelopmental disorders: Autism spectrum disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldarskard, G.F.; Spangmose, A.L.; Henningsen, A.A.; Wiingreen, R.; Mortensen, E.L.; Gundersen, T.W.; Jensen, R.B.; Knorr, S.; Damm, P.; Forman, J.L.; et al. Academic Performance in Adolescents Born to Mothers with Gestational Diabetes-A National Danish Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4554–e4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, Y.; Marks, D.J.; Grossman, B.; Yoon, M.; Loudon, H.; Stone, J.; Halperin, J.M. Exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus and low socioeconomic status: Effects on neurocognitive development and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.R.; Yu, T.; Lien, Y.J.; Chou, Y.Y.; Kuo, P.L. Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders and maternal diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2023, 65, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damtie, Y.; Dachew, B.A.; Ayano, G.; Tadesse, A.W.; Betts, K.; Alati, R. The risk of intellectual disability in offspring of diabetic mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2025, 192, 112115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Y.; Celis, C.; Acurio, J.; Escudero, C. Language Impairment in Children of Mothers with Gestational Diabetes, Preeclampsia, and Preterm Delivery: Current Hypothesis and Potential Underlying Mechanisms: Language Impartment and Pregnancy Complications. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1428, 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Xie, J.; Jiao, X.C.; Ma, S.S.; Liu, Y.; Yin, W.J.; Tao, R.X.; Hu, H.L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.X.; et al. Maternal Glycemia During Pregnancy and Early Offspring Development: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 2279–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, I.; Dalloul, M.; Hausser, J.; Vaday, D.; Gilboa, E.; Wang, L.; Hittelman, J.; Hoepner, L.; Fordjour, L.; Chitamanni, P.; et al. Role of one-carbon nutrient intake and diabetes during pregnancy in children’s growth and neurodevelopment: A 2-year follow-up study of a prospective cohort. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Espinola, F.J.; Berglund, S.K.; Garcia-Valdes, L.M.; Segura, M.T.; Jerez, A.; Campos, D.; Moreno-Torres, R.; Rueda, R.; Catena, A.; Perez-Garcia, M.; et al. Maternal Obesity, Overweight and Gestational Diabetes Affect the Offspring Neurodevelopment at 6 and 18 Months of Age—A Follow Up from the PREOBE Cohort. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornoy, A.; Wolf, A.; Ratzon, N.; Greenbaum, C.; Dulitzky, M. Neurodevelopmental outcome at early school age of children born to mothers with gestational diabetes. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 1999, 81, F10–F14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, G.; Boivin, M.; Seguin, J.R.; Perusse, D.; Tremblay, R.E. Gestational diabetes hinders language development in offspring. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e1073–e1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolseth, A.J.; Kulseth, S.; Stafne, S.N.; Morkved, S.; Salvesen, K.A.; Evensen, K.A.I. Physical health and neurodevelopmental outcome in 7-year-old children whose mothers were at risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Ito, S.; Miyashita, C.; Umazume, T.; Cho, K.; Watari, H.; Ito, Y.; Saijo, Y.; Kishi, R. Neurodevelopmental delay up to the age of 4 years in infants born to women with gestational diabetes mellitus: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J. Diabetes Investig. 2022, 13, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, A.H.; Wang, X.; Martinez, M.P.; Walthall, J.C.; Curry, E.S.; Page, K.; Buchanan, T.A.; Coleman, K.J.; Getahun, D. Association of maternal diabetes with autism in offspring. JAMA 2015, 313, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Surveill. Summ. 2012, 61, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, N.; Anixt, J.; Manning, P.; Ping, I.L.D.; Marsolo, K.A.; Bowers, K. Maternal metabolic risk factors for autism spectrum disorder-An analysis of electronic medical records and linked birth data. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, C.; Zou, M.Y.; Feng, F.M.; Liang, S.M.; Chen, W.X.; Wu, L.J. Association between maternal gestational diabetes mellitus and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2023, 25, 818–823. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Luan, S.; Liu, C. Association of maternal diabetes with autism spectrum disorders in offspring: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Norstedt, G.; Schalling, M.; Gissler, M.; Lavebratt, C. The Risk of Offspring Psychiatric Disorders in the Setting of Maternal Obesity and Diabetes. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, V.; Urquizu, X.; Valverde, M.; Macias, M.; Carmona, A.; Esteve, E.; Escribano, G.; Pons, N.; Gimenez, O.; Girones, T.; et al. Influence of Maternal Diabetes on the Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring in the Prenatal and Postnatal Periods. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuffrey, L.C.; Morales, S.; Jacobson, M.H.; Bosquet Enlow, M.; Ghassabian, A.; Margolis, A.E.; Lucchini, M.; Carroll, K.N.; Crum, R.M.; Dabelea, D.; et al. Association of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Perinatal Maternal Depression with Early Childhood Behavioral Problems: An Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Study. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1595–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Liu, G.; Han, B.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X. The association of maternal diabetes with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, R.A.; Avraam, D.; Guxens, M.; Julvez, J.; Harris, J.R.; Nader, J.T.; Cadman, T.; Elhakeem, A.; Strandberg-Larsen, K.; Marroun, H.E.; et al. Is maternal diabetes during pregnancy associated with neurodevelopmental, cognitive and behavioural outcomes in children? Insights from individual participant data meta-analysis in ten birth cohorts. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daraki, V.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Koutra, K.; Georgiou, V.; Kampouri, M.; Kyriklaki, A.; Vafeiadi, M.; Papavasiliou, S.; Kogevinas, M.; Chatzi, L. Effect of parental obesity and gestational diabetes on child neuropsychological and behavioral development at 4 years of age: The Rhea mother-child cohort, Crete, Greece. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2017, 26, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Deng, F.; Yan, S.; Huang, K.; Wu, X.; Tao, X.; Wang, S.; Tao, F. Gestational diabetes mellitus, autistic traits and ADHD symptoms in toddlers: Placental inflammatory and oxidative stress cytokines do not play an intermediary role. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 134, 105435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Ruiz, A.; Cerdo, T.; Jordano, B.; Torres-Espinola, F.J.; Escudero-Marin, M.; Garcia-Ricobaraza, M.; Bermudez, M.G.; Garcia-Santos, J.A.; Suarez, A.; Campoy, C. Maternal weight, gut microbiota, and the association with early childhood behavior: The PREOBE follow-up study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.Y.L.; Gao, L.; Hsieh, M.H.; Kjerpeseth, L.J.; Avelar, R.; Banaschewski, T.; Chan, A.H.Y.; Coghill, D.; Cohen, J.M.; Gissler, M.; et al. Maternal diabetes and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring in a multinational cohort of 3.6 million mother-child pairs. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersain, R.; Mishra, D.; Juneja, M.; Kumar, D.; Garg, S. Comparison of Neurodevelopmental Status in Early Infancy of Infants of Women with and Without Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Indian J. Pediatr. 2023, 90, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornoy, A.; Ratzon, N.; Greenbaum, C.; Wolf, A.; Dulitzky, M. School-age children born to diabetic mothers and to mothers with gestational diabetes exhibit a high rate of inattention and fine and gross motor impairment. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 14, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saros, L.; Lind, A.; Setanen, S.; Tertti, K.; Koivuniemi, E.; Ahtola, A.; Haataja, L.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Vahlberg, T.; et al. Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes mellitus, and diet in association with neurodevelopment of 2-year-old children. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 94, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijas, H.; Vaarasmaki, M.; Saarela, T.; Keravuo, R.; Raudaskoski, T. A follow-up of a randomised study of metformin and insulin in gestational diabetes mellitus: Growth and development of the children at the age of 18 months. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 122, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertti, K.; Eskola, E.; Ronnemaa, T.; Haataja, L. Neurodevelopment of Two-Year-Old Children Exposed to Metformin and Insulin in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2015, 36, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Peng, C.; Geng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Hou, X.; Liu, L. Emotional Prosodies Processing and Its Relationship with Neurodevelopment Outcome at 24 Months in Infants of Diabetic Mothers. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 861432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paavilainen, E.; Nyman, A.; Niinikoski, H.; Nikkinen, H.; Veijola, R.; Vaarasmaki, M.; Tossavainen, P.; Ronnemaa, T.; Tertti, K. Metformin Versus Insulin for Gestational Diabetes: Cognitive and Neuropsychological Profiles of Children Aged 9 years. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2023, 44, e642–e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veena, S.R.; Krishnaveni, G.V.; Srinivasan, K.; Kurpad, A.V.; Muthayya, S.; Hill, J.C.; Kiran, K.N.; Fall, C.H.D. Childhood cognitive ability: Relationship to gestational diabetes mellitus in India. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2134–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, A.R.; Kuhlmann, N.; Bryce, C.A.; Greba, Q.; Campanucci, V.A.; Howland, J.G. Chronic maternal hyperglycemia induced during mid-pregnancy in rats increases RAGE expression, augments hippocampal excitability, and alters behavior of the offspring. Neuroscience 2015, 303, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, B.; Odero, G.; Rozbacher, S.; Stevenson, M.; Kereliuk, S.M.; Pereira, T.J.; Dolinsky, V.W.; Kauppinen, T.M. Exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus induces neuroinflammation, derangement of hippocampal neurons, and cognitive changes in rat offspring. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, K.; Ren, J.; Luo, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, C.; Tan, C.; Lv, P.; Sun, X.; Sheng, J.; Liu, X.; et al. Intrauterine hyperglycemia impairs memory across two generations. Transl. Psychiatr. 2021, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.M.; Smith, A.; Chow, T.; Negriff, S.; Carter, S.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A. Prenatal Exposure to Gestational Diabetes Mellitus is Associated with Mental Health Outcomes and Physical Activity has a Modifying Role. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.M.; Yunker, A.G.; DeFendis, A.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A. Prenatal exposure to gestational diabetes is associated with anxiety and physical inactivity in children during COVID-19. Clin. Obes. 2021, 11, e12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, J.M.; Goldsworthy, M.R.; Hague, W.M.; Coat, S.; Pitcher, J.B. Cortical Plasticity and Interneuron Recruitment in Adolescents Born to Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Rosella, L.C.; Oskoui, M.; Watson, T.; Yang, S. In utero Exposure to Maternal Diabetes and the Risk of Cerebral Palsy: A Population-based Cohort Study. Epidemiology 2023, 34, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Tan, X.; Wei, Y.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Cai, X.; et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Rats Induce Anxiety-Depression-Like Behavior in Offspring: Association with Neuroinflammation and NF-kappaB Pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 12047–12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.G.; Woodside, B.; Kiss, A.C.I. Effects of maternal mild hyperglycemia associated with snack intake on offspring metabolism and behavior across the lifespan. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 276, 114483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Seamans, M.; Nianogo, R.; Janzen, C.; Fei, Z.; Chen, L. Gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in young offspring: Does the risk differ by race and ethnicity? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2024, 6, 101217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, A.H.; Lin, J.C.; Chow, T.; Martinez, M.P.; Negriff, S.; Page, K.A.; McConnell, R.; Carter, S.A. Types of diabetes during pregnancy and risk of depression and anxiety in offspring from childhood to young adulthood. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, A.H.; Wang, X.; Martinez, M.P.; Getahun, D.; Page, K.A.; Buchanan, T.A.; Feldman, K. Maternal Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1 Diabetes, and Type 2 Diabetes During Pregnancy and Risk of ADHD in Offspring. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2502–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Su, T.; Yang, L.; Xi, L.; Wang, H.J.; Ji, Y. Maternal Glycemia and Its Pattern Associated with Offspring Neurobehavioral Development: A Chinese Birth Cohort Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Persson, M.; Wang, R.; Dalman, C.; Lee, B.K.; Karlsson, H.; Gardner, R.M. Random capillary glucose levels throughout pregnancy, obstetric and neonatal outcomes, and long-term neurodevelopmental conditions in children: A group-based trajectory analysis. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fallin, M.D.; Riley, A.; Landa, R.; Walker, S.O.; Silverstein, M.; Caruso, D.; Pearson, C.; Kiang, S.; Dahm, J.L.; et al. The Association of Maternal Obesity and Diabetes with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Obel, C.L.; Li, F.; Li, J. Five-Minute Apgar Score and the Risk of Mental Disorders During the First Four Decades of Life: A Nationwide Registry-Based Cohort Study in Denmark. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 796544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, A.; Yang, Z.; Tamashiro, R.; Isik, O.; Landau, R.; Miles, C.H.; Ungern-Sternberg, B.S.V.; Whitehouse, A.; Li, G.; Pennell, C.E.; et al. Mode of delivery and behavioral and neuropsychological outcomes in children at 10 years of age. J. Perinat. Med. 2024, 52, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orri, M.; Pingault, J.B.; Turecki, G.; Nuyt, A.M.; Tremblay, R.E.; Cote, S.M.; Geoffroy, M.C. Contribution of birth weight to mental health, cognitive and socioeconomic outcomes: Two-sample Mendelian randomisation. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2021, 219, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, C.; Marino, C.; Nosarti, C.; Vieno, A.; Visentin, S.; Simonelli, A. Association of Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Small for Gestational Age Status with Childhood Cognitive Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Leung, G.M.; Lam, H.S.; Schooling, C.M. Gestational age and adolescent mental health: Evidence from Hong Kong’s ‘Children of 1997’ birth cohort. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Tashiro, S.; Liu, P.J. Effects of Dietary Approaches and Exercise Interventions on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, S.H.; van Zanden, J.J.; Hoogenberg, K.; Lutgers, H.L.; Klomp, A.W.; Korteweg, F.J.; van Loon, A.J.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.R.; van den Berg, P.P. New diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus and their impact on the number of diagnoses and pregnancy outcomes. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.J.; Dai, R.X.; Tian, C.Q.; Hu, C.L. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 1 year in offspring of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornoy, A.; Reece, E.A.; Pavlinkova, G.; Kappen, C.; Miller, R.K. Effect of maternal diabetes on the embryo, fetus, and children: Congenital anomalies, genetic and epigenetic changes and developmental outcomes. Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2015, 105, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faleschini, S.; Doyon, M.; Arguin, M.; Lepage, J.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Van Lieshout, R.J.; Perron, P.; Bouchard, L.; Hivert, M.F. Maternal Hyperglycemia in Pregnancy and Offspring Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors. Matern. Child Health J. 2023, 27, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.H.; Song, Y.F.; Yao, Y.M.; Yin, J.; Wang, D.G.; Gao, L.P. Retardation of fetal dendritic development induced by gestational hyperglycemia is associated with brain insulin/IGF-I signals. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2014, 37, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, F.V.; Segabinazi, E.; de Meireles, A.L.F.; Mega, F.; Spindler, C.F.; Augustin, O.A.; Salvalaggio, G.D.S.; Achaval, M.; Kruse, M.S.; Coirini, H.; et al. Severe Uncontrolled Maternal Hyperglycemia Induces Microsomia and Neurodevelopment Delay Accompanied by Apoptosis, Cellular Survival, and Neuroinflammatory Deregulation in Rat Offspring Hippocampus. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 39, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Gao, Y.M. Hyperglycemic condition disturbs the proliferation and cell death of neural progenitors in mouse embryonic spinal cord. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spauwen, P.J.; van Eupen, M.G.; Kohler, S.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Verhey, F.R.; van der Kallen, C.J.; Sep, S.J.S.; Koster, A.; Schaper, N.C.; Dagnelie, P.C.; et al. Associations of advanced glycation end-products with cognitive functions in individuals with and without type 2 diabetes: The maastricht study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Petroianu, G.; Adem, A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, L.; Niu, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Maternal Diabetes-Induced Suppression of Oxytocin Receptor Contributes to Social Deficits in Offspring. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 634781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, C.A.; Piroli, G.G.; Lawrence, R.C.; Wrighten, S.A.; Green, A.J.; Wilson, S.P.; Sakai, R.R.; Kelly, S.J.; Wilson, M.A.; Mott, D.D.; et al. Hippocampal Insulin Resistance Impairs Spatial Learning and Synaptic Plasticity. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3927–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Moore, E.; Meiri, N.; Quon, M.J.; Alkon, D.L. Brain insulin receptors and spatial memory. Correlated changes in gene expression, tyrosine phosphorylation, and signaling molecules in the hippocampus of water maze trained rats. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 34893–34902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C.M.; Mohamed Yusof, N.I.S.; Abdul Aziz, S.H.; Mohd Fauzi, F. Maternal Cognitive Impairment Associated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus-A Review of Potential Contributing Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Fusco, S.; Grassi, C. Brain Insulin Resistance and Hippocampal Plasticity: Mechanisms and Biomarkers of Cognitive Decline. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, A.; Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Han, T.; Zhang, H.; Baker, P.N. Metformin administration during pregnancy attenuated the long-term maternal metabolic and cognitive impairments in a mouse model of gestational diabetes. Aging 2020, 12, 14019–14036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, M.E.; Marka, N.; Lunos, S.; Nagel, E.M.; Gonzalez Villamizar, J.D.; Nathan, B.; Ramel, S. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 as early predictors of growth, body composition, and neurodevelopment in preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2024, 44, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmazer, E.; Solak, N. Correlation between inflammatory markers and insulin resistance in pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 35, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, A.S. Inflammatory Markers in Older Women with a History of Gestational Diabetes and the Effects of Weight Loss. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 5172091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Money, K.M.; Barke, T.L.; Serezani, A.; Gannon, M.; Garbett, K.A.; Aronoff, D.M.; Mirnics, K. Gestational diabetes exacerbates maternal immune activation effects in the developing brain. Mol. Psychiatr. 2018, 23, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Apaijai, N.; Oo, T.T.; Suntornsaratoon, P.; Charoenphandhu, N.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Gestational diabetes mellitus, not obesity, triggers postpartum brain inflammation and premature aging in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neuroscience 2024, 559, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorska-Ciebiada, M.; Saryusz-Wolska, M.; Borkowska, A.; Ciebiada, M.; Loba, J. Serum levels of inflammatory markers in depressed elderly patients with diabetes and mild cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magaki, S.; Mueller, C.; Dickson, C.; Kirsch, W. Increased production of inflammatory cytokines in mild cognitive impairment. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.U.; Chung, S.W.; Kim, Y.D.; Maeng, L.S. Relationship between the hs-CRP as non-specific biomarker and Alzheimer’s disease according to aging process. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 12, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, M.; Hiden, U.; Desoye, G.; Froehlich, J.; Hauguel-de Mouzon, S.; Jawerbaum, A. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 3061–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Ren, J.; Ma, L. Changes in Oxidative Stress Markers in Pregnant Women of Advanced Maternal Age with Gestational Diabetes and Their Predictive Value for Neurodevelopmental Impact. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4003–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemse, N.; Chhetri, S.; Joshi, S. Beneficial effects of dietary omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on offspring brain development in gestational diabetes mellitus. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2024, 202, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Kakongoma, N.; Hua, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; He, S.; Gu, H.; Shi, J.; Hu, W. DNA methylation and expression profiles of placenta and umbilical cord blood reveal the characteristics of gestational diabetes mellitus patients and offspring. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.S.; Zou, K.X.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, Y.S.; Sheng, J.Z.; Huang, H.F.; Ding, G.L. Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals the Effect of Maternal Gestational Diabetes on Fetal Mouse Hippocampi. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 748862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, C.G.; Cox, B.; Fore, R.; Jungius, J.; Kvist, T.; Lent, S.; Miles, H.E.; Salas, L.A.; Rifas-Shiman, S.; Starling, A.P.; et al. Maternal Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Newborn DNA Methylation: Findings From the Pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics Consortium. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canouil, M.; Khamis, A.; Keikkala, E.; Hummel, S.; Lobbens, S.; Bonnefond, A.; Delahaye, F.; Tzala, E.; Mustaniemi, S.; Vaarasmaki, M.; et al. Epigenome-Wide Association Study Reveals Methylation Loci Associated with Offspring Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Exposure and Maternal Methylome. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 1992–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Pineda, T.; Pena-Montero, N.; Fragoso-Bargas, N.; Gutierrez-Repiso, C.; Lima-Rubio, F.; Suarez-Arana, M.; Sanchez-Pozo, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Molina-Vega, M.; Picon-Cesar, M.J.; et al. Epigenetic marks associated with gestational diabetes mellitus across two time points during pregnancy. Clin. Epigenet. 2023, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Pineda, T.M.; Pena-Montero, N.; Gutierrez-Repiso, C.; Lima-Rubio, F.; Sanchez-Pozo, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Molina-Vega, M.; Picon-Cesar, M.J.; Morcillo, S. Epigenome wide association study in peripheral blood of pregnant women identifies potential metabolic pathways related to gestational diabetes. Epigenetics 2023, 18, 2211369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Cardenas, A.; Perron, P.; Hivert, M.F.; Bouchard, L.; Greenwood, C.M.T. Detecting cord blood cell type-specific epigenetic associations with gestational diabetes mellitus and early childhood growth. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.J.; Huang, R.; Zheng, T.; Du, Q.; Yang, M.N.; Xu, Y.J.; Liu, X.; Tao, M.Y.; He, H.; Fang, F.; et al. Genome-Wide Placental Gene Methylations in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, Fetal Growth and Metabolic Health Biomarkers in Cord Blood. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 875180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Yan, S. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of fetal hemodynamic parameters in pregnant women with diabetes mellitus in the third trimester of pregnancy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatihoglu, E.; Aydin, S.; Karavas, E.; Kantarci, M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Early Hemodynamic Changes in Fetus. J. Med. Ultrasound. 2021, 29, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B.; Scuteri, A.; Black, S.E.; Decarli, C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Iadecola, C.; Launer, L.J.; Laurent, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Nyenhuis, D.; et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2011, 42, 2672–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biete, M.; Vasudevan, S. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Impacts on fetal neurodevelopment, gut dysbiosis, and the promise of precision medicine. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1420664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, J.; Shi, W.; Du, N.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, P.; Zhang, F.; Jia, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dysbiosis of maternal and neonatal microbiota associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gut 2018, 67, 1614–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Tam, W.H.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Xu, W.; Yan, S.; Qin, B.; Lin, L.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, J.; et al. Maternal gestational diabetes mellitus associates with altered gut microbiome composition and head circumference abnormalities in male offspring. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1192–1206e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, Q.; Shan, D.; Pan, X.; Hu, Y. Unraveling the role of the gut microbiome in pregnancy disorders: Insights and implications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1521754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagadeesan, G.; Das, T.K.; Mendoza, J.M.; Alrousan, G.; Blasco-Conesa, M.P.; Thangaraj, P.; Ganesh, B.P. Effects of Prebiotic Phytocompound Administration in Gestational Diabetic Dams and Its Influence on Offspring Cognitive Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, M.; Zhao, J.H.; Ruan, B. Altered gut microbiota profile in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 104, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Carrozzino, D.; Fraticelli, F.; Fulcheri, M.; Vitacolonna, E. Quality of Life in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 7058082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yu, H.; Ke, X.; Eyles, D.; Sun, R.; Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Lin, L.; McGrath, J.J.; Lu, J.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency worsens maternal diabetes induced neurodevelopmental disorder by potentiating hyperglycemia-mediated epigenetic changes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1491, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taousani, E.; Savvaki, D.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Mintziori, G.; Theodoridou, A.; Koukou, Z.; Goulis, D.G. The effects of exercise on anxiety symptoms in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A pilot study. Hormones 2025, 24, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Huang, J. Effect of high-quality nursing on blood glucose level, psychological state, and treatment compliance of patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 13084–13092. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Chung, C. Effects of nursing intervention programs for women with gestational diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2021, 27, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Luo, Y. Influence of mHealth-Based Lifestyle Interventions on Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression of Women with Gestational Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2024, 33, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Pu, J.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Tang, J. GDM-Related Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders in the Mothers and Their Progeny, and the Underlying Mechanisms. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010019

Yan Z, Pu J, Li D, Liu M, Xu Z, Tang J. GDM-Related Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders in the Mothers and Their Progeny, and the Underlying Mechanisms. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zhijin, Jianhong Pu, Dawei Li, Mingxing Liu, Zhice Xu, and Jiaqi Tang. 2026. "GDM-Related Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders in the Mothers and Their Progeny, and the Underlying Mechanisms" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010019

APA StyleYan, Z., Pu, J., Li, D., Liu, M., Xu, Z., & Tang, J. (2026). GDM-Related Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders in the Mothers and Their Progeny, and the Underlying Mechanisms. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010019