Uncovering Sex and Gender Differences in Sarcoidosis: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

2.1.1. Search Strategy

2.1.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Original clinical studies (randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective observational studies)

- Multicentric or monocentric study design

- Enrolment of patients with an established diagnosis of sarcoidosis

- Full-text availability

- Reporting data on biological sex, gender, and/or gender-related clinical outcomes

- No age restrictions were applied

- Case reports

- Editorials

- Narrative reviews or systematic reviews

- Pre-print articles

- Studies not reporting outcomes relevant to sex- or gender-related differences

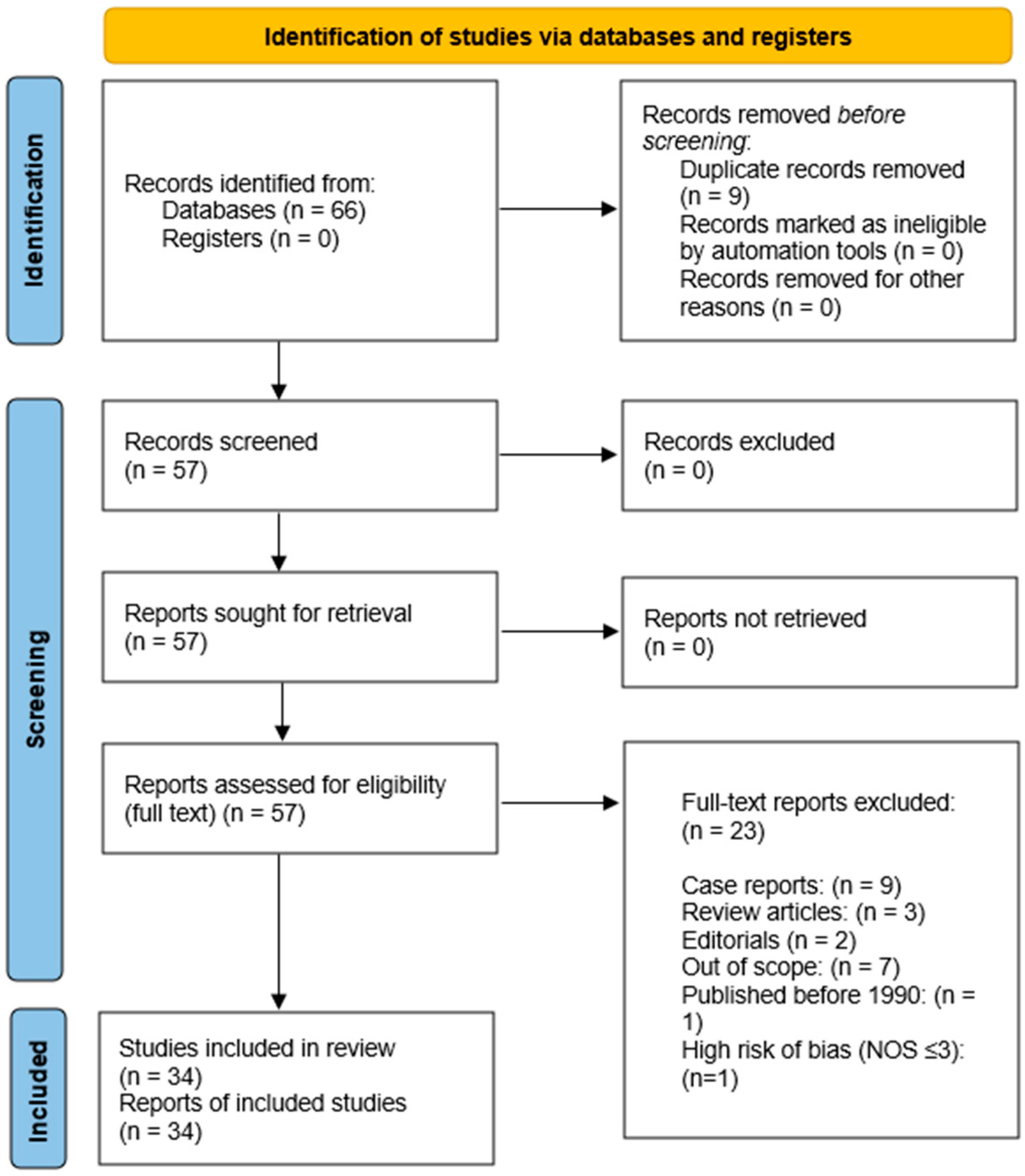

2.1.3. Study Selection Process

2.1.4. Data Extraction

- Study design

- Sample size

- Age and sex distribution

- Clinical presentation

- Quality of life measures

- Illness perception outcomes

2.1.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.1.6. Data Synthesis

- Biological sex and disease presentation

- Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life

2.2. Protocol Registration

3. Results

3.1. Biological Sex and Disease Presentation

3.1.1. Sex Differences in Age at Disease Onset

3.1.2. Sex Differences in Extrapulmonary Organ Involvement

Skin Involvement

Ocular Involvement

Cardiac Involvement

Other Organ Involvement

3.1.3. Sex Differences in Pulmonary Sarcoidosis

3.2. Gender Differences in Illness Perception and Quality of Life

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | N | Population | Main Study Domain | Outcomes Assessed | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lundkvist et al., 2022 [34] | Sweden | Retrospective observational, multicentric | 1429 | Adults with pulmonary sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Age at diagnosis, radiological stage, extrapulmonary manifestations | Male sex was associated with younger age at diagnosis and more frequent radiological stage II, whereas female sex was associated with skin and salivary gland involvement. |

| Lill et al., 2014/2016 [35] | Estonia | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 230 | Sarcoidosis outpatients | Biological sex and disease presentation | FEV1, DLCO, FVC, extrapulmonary involvement | Female sex was associated with older age, lower smoking prevalence, greater extrapulmonary and musculoskeletal involvement, lower FEV1 and DLCO, and higher FVC % predicted. |

| Ungprasert et al., 2017 [36] | USA | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 345 | Incident sarcoidosis cases | Biological sex and disease presentation | Age, pulmonary and extrapulmonary involvement, ACE, calcium | Female sex was associated with older age at diagnosis and higher frequency of uveitis and cutaneous involvement, whereas male sex was associated with more frequent respiratory symptoms. |

| Haraldsdóttir et al., 2021 [37] | Iceland | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 418 | Tissue verified sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Incidence, age, smoking | Female sex was associated with older age at diagnosis, whereas incidence rates were similar between sexes. |

| Varron et al., 2012 [38] | France | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 100 | Late onset and younger sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Clinical phenotype, survival, treatment | Female sex was associated with higher frequency of late onset sarcoidosis, with more frequent asthenia, uveitis, and skin lesions in older patients. |

| Dumas et al., 2016 [39] | USA | Prospective observational, multicentric | 377 | Female nurses with sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Prevalence and incidence | Female sex showed increasing sarcoidosis incidence with age, with markedly higher prevalence and incidence among Black women. |

| Yanardag et al., 2003 [40] | Turkey | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 170 | Cutaneous sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Skin phenotypes and lung involvement | Female sex showed marked predominance in cutaneous sarcoidosis, with erythema nodosum as the most frequent lesion. |

| Liu et al., 2017 [41] | Taiwan | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 38 | Biopsy proven cutaneous sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Demographics, comorbidities | Female sex was strongly predominant and associated with older age and facial involvement. |

| Grunewald & Eklund, 2007 [42] | Sweden | Prospective observational, monocentric | 150 | Löfgren syndrome | Biological sex and disease presentation | EN, ankle arthritis, outcome | Female sex was associated with higher frequency of erythema nodosum, whereas male sex was associated with isolated ankle arthritis. |

| Soheilian et al., 2004 [43] | Iran | Prospective observational, monocentric | 544 | Uveitis patients | Biological sex and disease presentation | Etiology and anatomy | Female sex was associated with a higher frequency of sarcoidosis among patients with intermediate uveitis. |

| Kitamei et al., 2009 [44] | Japan | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 1240 | Intraocular inflammation | Biological sex and disease presentation | Etiology, age, sex | Female sex predominated among sarcoidosis related uveitis, whereas male sex was associated with younger onset. |

| Chung et al., 2007 [45] | Taiwan | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 60 | Sarcoidosis with uveitis | Biological sex and disease presentation | CT, uveitis pattern | Female sex showed marked predominance with peak onset in the sixth decade and predominant posterior segment involvement. |

| Ohara et al., 1992 [46] | Japan | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 159 | Systemic sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Type of intraocular lesions | Ocular involvement was highly prevalent in both sexes, with iritis as the most frequent manifestation. |

| Lobo et al., 2003 [47] | UK | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 75 | Sarcoid uveitis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Visual outcome | Severe visual loss was more frequent in panuveitis and multifocal choroiditis than in anterior uveitis. |

| Williamson et al., 2025 [48] | USA | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 455 | Cardiac sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Symptoms, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), arrhythmias, hospitalizations, survival | Female sex was associated with more severe symptoms at presentation, whereas survival and arrhythmic outcomes were similar between sexes. |

| Martusewicz Boros et al., 2016 [49] | Poland | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 1375 | Biopsy proven sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | MRI confirmed cardiac involvement | Male sex was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of cardiac sarcoidosis. |

| Kalra et al., 2021 [50] | USA | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 324 | Suspected cardiac sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), arrhythmias, death | Female sex was associated with fewer ventricular arrhythmias and less extensive LGE, while mortality did not differ between sexes. |

| Iso et al., 2023 [51] | Japan | Retrospective observational, multicentric | 512 | Cardiac sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Ventricular arrhythmias, LVEF, survival | Male sex was independently associated with a higher risk of potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias. |

| Duvall et al., 2023 [52] | USA | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 252 | Cardiac sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Heart failure (HF), arrhythmias, LVAD, transplant, death | Female sex was associated with more frequent symptomatic heart failure, whereas male sex was independently associated with higher arrhythmic risk. |

| Ahmed et al., 2024 [53] | USA | Retrospective observational, multicentric | 760 | Cardiac sarcoidosis with ICD | Biological sex and disease presentation | Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), Acute kidney injury (AKI), Sudden cardiac death (SCD) | Male sex was associated with higher ICD utilization and a higher risk of sudden cardiac death, whereas female sex was independently associated with a lower adjusted risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and acute kidney injury. |

| Nakasuka et al., 2023 [54] | Japan | Retrospective observational, multicentric | 430 | Cardiac sarcoidosis with CRT | Biological sex and disease presentation | Mortality, HF death, arrhythmias, BNP, LVEF | Female sex was independently associated with better ventricular arrhythmia free and cardiac adverse event free survival after CRT, while heart failure death free survival was similar between sexes. |

| Judson et al., 2012 [55] | USA | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 1774 | Tertiary sarcoidosis clinic patients | Biological sex and disease presentation | Organ distribution, treatment | Male sex was associated with more lung and cardiac involvement, whereas female sex was associated with skin, ocular, hepatic, and lymph node involvement. |

| Brito Zerón et al., 2016 [56] | Spain | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 175 | Consecutive sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | 2014 WASOG organ involvement | Female sex was associated with a higher frequency of cutaneous and musculoskeletal involvement and a lower frequency of hypercalcaemia, whereas male sex was associated with higher pulmonary involvement. |

| Salari et al., 2014 [57] | Iran | Cross sectional, monocentric | 30 | Musculoskeletal sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Joint, bone, muscle involvement | Female sex predominated markedly and was associated with a high frequency of sarcoidal arthropathy. |

| Westney et al., 2007 [58] | USA | Cross sectional, monocentric | 165 | African American sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | Scadding stage, comorbid illness | Female sex was associated with a higher burden of chronic comorbid illnesses, whereas male sex showed a trend toward more severe chest radiographic stages. |

| Sharp et al., 2023 [59] | USA | Retrospective observational, monocentric | 602 | Sarcoidosis with PFTs | Biological sex and disease presentation | FEV1, FVC, DLCO | Male sex was associated with a higher prevalence of obstructive lung disease, whereas female sex was associated with a higher prevalence of restrictive impairment. |

| Krell et al., 2012 [60] | USA | Prospective observational, monocentric | 518 | Biopsy proven sarcoidosis | Biological sex and disease presentation | DLCO, airflow limitation | Female sex and smoking were independently associated with a greater reduction in DLCO, with the most pronounced impairment observed in female smokers. |

| Bardakci et al., 2024 [61] | Turkey | Prospective observational, monocentric | 189 | Pulmonary sarcoidosis | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | SF 36, FAS, FSS, spirometry, ACE | Female sex was associated with significantly lower SF 36 scores and higher fatigue severity. |

| Hinz et al., 2012 [62] | Germany | Cross sectional, multicentric | 1197 | Sarcoidosis society members | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | HADS, dyspnoea, comorbidities | Female sex was associated with higher depression scores in univariate analysis. |

| Dudvarski Ilić et al., 2009 [63] | Serbia | Prospective observational, monocentric | 202 | Biopsy proven sarcoidosis | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | SHQ | Women had significantly lower emotional, physical and total SHQ scores before therapy and lower physical scores after treatment. |

| De Vries et al., 1999 [64] | The Netherlands | Cross sectional, multicentric | 1026 | Sarcoidosis society members | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | WHOQoL 100, symptom checklist, medication use | Women reported a higher symptom burden, lower physical and psychological quality of life, and higher use of analgesics, NSAIDs and ophthalmic treatments, whereas men more frequently used oral corticosteroids. |

| Gwadera et al., 2021 [65] | Poland | Prospective observational, monocentric | 75 | Non smoking sarcoidosis | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | SHQ | Women showed significantly lower total and physical SHQ scores despite no sex differences in lung function or activity. |

| Bourbonnais et al., 2010 [66] | USA | Cross sectional, monocentric | 221 | Biopsy proven sarcoidosis | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | SF 36, SHQ, PFT, 6MWT, Borg | Women had significantly lower HRQoL across all domains; predictors differed by sex. |

| Bączek et al., 2025 [67] | UK | Retrospective observational, multicentric | 1071 | Pulmonary sarcoidosis | Gender differences in illness perception and quality of life | Age, symptoms, comorbidities, lung function, treatment | Women were older at diagnosis and reported more fatigue and higher ESR, whereas men showed higher rates of lymphopenia, elevated ACE, arrhythmia and methotrexate use; male sex and non white ethnicity were independently associated with initiation of immunosuppressive treatment. |

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 6MWT | 6-min walking test |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| HRQL | Health-related quality of life |

| IL | interleukin |

| ICD | implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| ILD | Interstitial lung disease |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MHT | menopausal hormone therapy |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trial |

References

- Xu, D.; Tao, X.; Fan, Y.; Teng, Y. Sarcoidosis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waly, Y.M.; Sharafeldin, A.-B.K.; Akhtar, M.U.; Chilmeran, Z.; Fredericks, S. A Review of Sarcoidosis Etiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1558049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, A.; Pisani, M.; Glassberg, M.K.; Bourjeily, G.; D’Ambrosio, C. Sex and Gender in Lung Disease and Sleep Disorders: A State-of-the-Art Review. Chest 2022, 162, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, R.K.; Cullen, K.M. Sarcoidosis: Key Disease Aspects and Update on Management. Clin. Med. 2025, 25, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miedema, J.R.; Bonella, F.; Buschulte, K.; Culver, D.A.; Jeny, F.; Obi, O.N.; Rivera, N.V.; Spagnolo, P.; Veltkamp, M.; Wijsenbeek, M. Sarcoidosis: A State-of-the-Art Review. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 2501324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belperio, J.A.; Fishbein, M.C.; Abtin, F.; Channick, J.; Balasubramanian, S.A.; Lynch Iii, J.P. Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: A Comprehensive Review: Past to Present. J. Autoimmun. 2024, 149, 103107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Kouranos, V.; Singh-Curry, V.; El Jammal, T.; Rosenbach, M. Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis. J. Autoimmun. 2024, 149, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungprasert, P.; Ryu, J.H.; Matteson, E.L. Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Sarcoidosis. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 3, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’alessandro, M.; Pianigiani, T.; Bergantini, L.; Cameli, P.; Bargagli, E.; Balestro, E.; Börner, E.; Bonella, F. Online Survey on Existing Sarcoidosis Registries and Biobanks: An ERN Lung Initiative. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2024, 41, e2024063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melani, A.S.; Simona, A.; Armati, M.; d’Alessandro, M.; Bargagli, E. A Comprehensive Review of Sarcoidosis Diagnosis and Monitoring for the Pulmonologist. Pulm. Ther. 2021, 7, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belperio, J.A.; Shaikh, F.; Abtin, F.; Fishbein, M.C.; Saggar, R.; Tsui, E.; Lynch, J.P. Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis with a Focus on Cardiac, Nervous System, and Ocular Involvement. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 37, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.S.; Pereira, I.A.; Sztajnbok, F.; Neto, N.S.R. Sarcoidosis: A General Overview. Adv. Rheumatol. 2024, 64, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, A.K. Treatment of Sarcoidosis: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 545413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, O.; Suzuki, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Kudo, A. Incidence and Baseline Characteristics of Relapse or Exacerbation in Patients with Pulmonary Sarcoidosis in Japan. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2021, 38, e2021026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, J.; Grutters, J.C.; Arkema, E.V.; Saketkoo, L.A.; Moller, D.R.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Sarcoidosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeyre, D.; Brauner, M.; Bernaudin, J.-F.; Carbonnelle, E.; Duchemann, B.; Rotenberg, C.; Berger, I.; Martin, A.; Nunes, H.; Naccache, J.-M.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: A Review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1150751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.; Yadav, D.; Puranik, N.; Guleria, R.; Jin, J.-O. Sarcoidosis: Causes, Diagnosis, Clinical Features, and Treatments. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouser, E.D.; Maier, L.A.; Wilson, K.C.; Bonham, C.A.; Morgenthau, A.S.; Patterson, K.C.; Abston, E.; Bernstein, R.C.; Blankstein, R.; Chen, E.S.; et al. Diagnosis and Detection of Sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, e26–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vender, R.J.; Aldahham, H.; Gupta, R. The Role of PET in the Management of Sarcoidosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2022, 28, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régis, C.; Benali, K.; Rouzet, F. FDG PET/CT Imaging of Sarcoidosis. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2023, 53, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.; McDermott, M.; McManus, G.; Franciosi, A.N.; Keane, M.P.; McGrath, E.E.; McCarthy, C.; Murphy, D.J. Meta-Analysis of [18F]FDG-PET/CT in Pulmonary Sarcoidosis. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossides, M.; Darlington, P.; Kullberg, S.; Arkema, E.V. Sarcoidosis: Epidemiology and Clinical Insights. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 293, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkema, E.V.; Cozier, Y.C. Sarcoidosis Epidemiology: Recent Estimates of Incidence, Prevalence and Risk Factors. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hena, K.M. Sarcoidosis Epidemiology: Race Matters. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 537382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, A.G.; Henriksen, A.H.; Sorger, H.; Naustdal, T.; Nilsen, T.I.L.; Romundstad, P.R.; Langhammer, A.; Romundstad, S. Prevalence, Incidence, and Mortality Associated with Sarcoidosis over Three Decades in the HUNT Study in Norway. Respir. Med. 2025, 241, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedahmed, M.I.; Baugh, A.D.; Albirair, M.T.; Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; McCulloch, C.E.; Whooley, M.A.; Koth, L.L.; Arjomandi, M. Epidemiology of Sarcoidosis in U.S. Veterans from 2003 to 2019. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2023, 20, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Lower, E.E.; Li, H.; Farhey, Y.; Baughman, R.P. Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Bone Sarcoidosis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2017, 47, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, A.; Bellenghi, M.; Ferroni, E.; Mangia, C.; Marconi, M.; Rizza, P.; Borghini, A.; Martini, L.; Luciani, M.N.; Ortona, E.; et al. Recommendations for the Application of Sex and Gender Medicine in Preclinical, Epidemiological and Clinical Research. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajcsanyi, L.S.; Jochimsen, M.A.; Kindler-Röhrborn, A.; Hinney, A. Redesigning Medicine: Integrating Sex and Gender for Better Health Outcomes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025; Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, D.; Chitnis, T.; Kaiser, U.B.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Rexrode, K.M.; Pennell, P.B.; Goldstein, J.M.; O’Neal, M.A.; LeBoff, M.; Behn, M.; et al. Clinical Advances in Sex- and Gender-Informed Medicine to Improve the Health of All: A Review. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Artiles, R.; Gebhard, C.E.; Gebhard, C. Integrating Gender Medicine into Modern Healthcare: Progress and Barriers. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 55, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.-J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L.; et al. Sex and Gender: Modifiers of Health, Disease, and Medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundkvist, A.; Kullberg, S.; Arkema, E.V.; Cedelund, K.; Eklund, A.; Grunewald, J.; Darlington, P. Differences in Disease Presentation between Men and Women with Sarcoidosis: A Cohort Study. Respir. Med. 2022, 191, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lill, H.; Kliiman, K.; Altraja, A. Factors Signifying Gender Differences in Clinical Presentation of Sarcoidosis among Estonian Population. Clin. Respir. J. 2016, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungprasert, P.; Crowson, C.S.; Matteson, E.L. Influence of Gender on Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of Sarcoidosis: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study 1976–2013. Lung 2017, 195, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraldsdóttir, S.Ó.; Jonasson, J.G.; Jorundsdottir, K.B.; Hannesson, H.J.; Gislason, T.; Gudbjornsson, B. Sarcoidosis in Iceland: A Nationwide Study of Epidemiology, Clinical Picture and Environmental Exposure. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00550-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varron, L.; Cottin, V.; Schott, A.-M.; Broussolle, C.; Sève, P. Late-Onset Sarcoidosis: A Comparative Study. Medicine 2012, 91, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, O.; Abramovitz, L.; Wiley, A.S.; Cozier, Y.C.; Camargo, C.A. Epidemiology of Sarcoidosis in a Prospective Cohort Study of U.S. Women. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanardağ, H.; Pamuk, O.N.; Karayel, T. Cutaneous Involvement in Sarcoidosis: Analysis of the Features in 170 Patients. Respir. Med. 2003, 97, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-L.; Tsai, W.-C.; Lee, C.-H. Cutaneous Sarcoidosis: A Retrospective Case Series and a Hospital-Based Case-Control Study in Taiwan. Medicine 2017, 96, e8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, J.; Eklund, A. Sex-Specific Manifestations of Löfgren’s Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheilian, M.; Heidari, K.; Yazdani, S.; Shahsavari, M.; Ahmadieh, H.; Dehghan, M. Patterns of Uveitis in a Tertiary Eye Care Center in Iran. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2004, 12, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamei, H.; Kitaichi, N.; Namba, K.; Kotake, S.; Goda, C.; Kitamura, M.; Miyazaki, A.; Ohno, S. Clinical Features of Intraocular Inflammation in Hokkaido, Japan. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009, 87, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-M.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liu, Y.-T.; Chang, S.-C.; Liu, H.-N.; Hsu, W.-H. Uveitis with Biopsy-Proven Sarcoidosis in Chinese—A Study of 60 Patients in a Uveitis Clinic over a Period of 20 Years. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2007, 70, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, K.; Okubo, A.; Sasaki, H.; Kamata, K. Intraocular Manifestations of Systemic Sarcoidosis. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 1992, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, A.; Barton, K.; Minassian, D.; du Bois, R.M.; Lightman, S. Visual Loss in Sarcoid-Related Uveitis. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2003, 31, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K.A.; Davison, J.M.; Rosenbaum, A.N.; Chareonthaitawee, P.; Kolluri, N.; Bois, J.P.; Abou Ezzeddine, O.F.; Schirger, J.A.; Kapa, S.; Siontis, K.C.; et al. Sex Differences in Cardiac Sarcoidosis. IJC Heart Vasc. 2025, 61, 101777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martusewicz-Boros, M.M.; Boros, P.W.; Wiatr, E.; Kempisty, A.; Piotrowska-Kownacka, D.; Roszkowski-Śliż, K. Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Is It More Common in Men? Lung 2016, 194, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, R.; Malik, S.; Chen, K.-H.A.; Ogugua, F.; Athwal, P.S.S.; Elton, A.C.; Velangi, P.S.; Ismail, M.F.; Chhikara, S.; Markowitz, J.S.; et al. Sex Differences in Patients with Suspected Cardiac Sarcoidosis Assessed by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, e009966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso, T.; Maeda, D.; Matsue, Y.; Dotare, T.; Sunayama, T.; Yoshioka, K.; Nabeta, T.; Naruse, Y.; Kitai, T.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. Sex Differences in Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Patients with Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Heart 2023, 109, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvall, C.; Pavlovic, N.; Rosen, N.S.; Wand, A.L.; Griffin, J.M.; Okada, D.R.; Tandri, H.; Kasper, E.K.; Sharp, M.; Chen, E.S.; et al. Sex and Race Differences in Cardiac Sarcoidosis Presentation, Treatment and Outcomes. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Jamil, Y.; Ramphul, K.; Mactaggart, S.; Bilal, M.; Singh Dulay, M.; Shi, R.; Azzu, A.; Okafor, J.; Memon, R.A.; et al. Sex Disparities in Cardiac Sarcoidosis Patients Undergoing Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakasuka, K.; Ishibashi, K.; Hattori, Y.; Mori, K.; Nakajima, K.; Nagayama, T.; Kamakura, T.; Wada, M.; Inoue, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; et al. Sex-Related Differences in the Prognosis of Patients with Cardiac Sarcoidosis Treated with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2022, 19, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, M.A.; Boan, A.D.; Lackland, D.T. The Clinical Course of Sarcoidosis: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment in a Large White and Black Cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2012, 29, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Sellarés, J.; Bosch, X.; Hernández, F.; Kostov, B.; Sisó-Almirall, A.; Lopez Casany, C.; Santos, J.M.; Paradela, M.; Sánchez, M.; et al. Epidemiologic Patterns of Disease Expression in Sarcoidosis: Age, Gender and Ethnicity-Related Differences. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2016, 34, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salari, M.; Rezaieyazdi, Z. Prevalence and Clinical Picture of Musculoskeletal Sarcoidosis. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e17918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westney, G.E.; Habib, S.; Quarshie, A. Comorbid Illnesses and Chest Radiographic Severity in African-American Sarcoidosis Patients. Lung 2007, 185, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, M.; Psoter, K.J.; Balasubramanian, A.; Pulapaka, A.V.; Chen, E.S.; Brown, S.-A.W.; Mathai, S.C.; Gilotra, N.A.; Chrispin, J.; Bascom, R.; et al. Heterogeneity of Lung Function Phenotypes in Sarcoidosis: Role of Race and Sex Differences. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2023, 20, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, W.; Bourbonnais, J.M.; Kapoor, R.; Samavati, L. Effect of Smoking and Gender on Pulmonary Function and Clinical Features in Sarcoidosis. Lung 2012, 190, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardakci, M.I.; Albayrak, G.A. Quality of Life, Fatigue and Markers in Sarcoidosis: A Section from Turkey. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2024, 41, e2024049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Brähler, E.; Möde, R.; Wirtz, H.; Bosse-Henck, A. Anxiety and Depression in Sarcoidosis: The Influence of Age, Gender, Affected Organs, Concomitant Diseases and Dyspnea. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2012, 29, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dudvarski-Ilić, A.; Mihailović-Vucinić, V.; Gvozdenović, B.; Zugić, V.; Milenković, B.; Ilić, V. Health Related Quality of Life Regarding to Gender in Sarcoidosis. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 837–840. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, J.; Van Heck, G.L.; Drent, M. Gender Differences in Sarcoidosis: Symptoms, Quality of Life, and Medical Consumption. Women Health 1999, 30, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwadera, Ł.; Białas, A.J.; Górski, W.; Iwański, M.A.; Miłkowska-Dymanowska, J.; Górski, P.; Piotrowski, W.J. Gender Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life Measured by the Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, J.M.; Samavati, L. Effect of Gender on Health Related Quality of Life in Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2010, 27, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bączek, K.K.; Cheng, S.L.; Amanda, G.; Achaiah, A.; Sesé, L.; Chaudhuri, N. Exploring Gender and Ethnic Disparities in Sarcoidosis: Insights from the British Thoracic Society UK Interstitial Lung Disease Registry. BMJ Open Resp. Res. 2025, 12, e003449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehara, M.; Sachs, M.C.; Kullberg, S.; Grunewald, J.; Blomberg, A.; Arkema, E.V. Reproductive and Hormonal Risk Factors for Sarcoidosis: A Nested Case–Control Study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciarra, F.; Campolo, F.; Franceschini, E.; Carlomagno, F.; Venneri, M.A. Gender-Specific Impact of Sex Hormones on the Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.P.; Liu, J.A.; Seddu, K.; Klein, S.L. Sex Hormone Signaling and Regulation of Immune Function. Immunity 2023, 56, 2472–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagts, C.; Ascoli, C.; Jacobson, J.R. Immunopathogenesis of Sarcoidosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 149, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, K.; Miura, K.; Ishiwata, T.; Takahashi, F.; Yoshioka, M.; Minakata, K.; Murakami, A.; Sasaki, S.; Iwakami, S.; Annoura, T.; et al. Sex Hormones Alter Th1 Responses and Enhance Granuloma Formation in the Lung. Respiration 2011, 81, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehara, M.; Kullberg, S.; Bixo, M.; Sachs, M.C.; Grunewald, J.; Arkema, E.V. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Sarcoidosis: A Population-Based Nested Case–Control Study in Sweden. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 39, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Flora, M.S.; Rahman, A.U. Influence of Estrogen Exposure on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Bangladeshi Women: A Case-Control Study Scenario. J. Health Res. 2021, 36, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patasova, K.; Dehara, M.; Mantel, Ä.; Bixo, M.; Arkema, E.V.; Holmqvist, M. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and the Risk of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Systemic Sclerosis: A Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 3563–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kale, T.; Yoo, L.; Kroeger, E.; Iqbal, A.; Kane, S.; Shihab, S.; Conley, S.; Kamp, K. Menopause and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 3443–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungaro, L.; Costanzini, A.; Manza, F.; Barbalinardo, M.; Gentili, D.; Guarino, M.; Caputo, F.; Zoli, G.; De Giorgio, R.; Caio, G. Impact of Female Gender in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Narrative Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, K.; Troll, W.; Callhoff, J.; Strangfeld, A.; Ohrndorf, S.; Mucke, J. Sex- and Gender-Related Differences in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Scoping Review. Rheumatol. Int. 2025, 45, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusbaum, J.S.; Mirza, I.; Shum, J.; Freilich, R.W.; Cohen, R.E.; Pillinger, M.H.; Izmirly, P.M.; Buyon, J.P. Sex Differences in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Epidemiology, Clinical Considerations, and Disease Pathogenesis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, M.A.; Thomeer, M.J.; Gosselink, R.; Wuyts, W.A.; Van Herck, E.; Bouillon, R.; Demedts, M.G.; Decramer, M. Hypogonadism in Male Outpatients with Sarcoidosis. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 2502–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Kullberg, S.; Garman, L.; Pezant, N.; Ellinghaus, D.; Vasila, V.; Eklund, A.; Rybicki, B.A.; Iannuzzi, M.C.; Schreiber, S.; et al. Sex Differences in the Genetics of Sarcoidosis across European and African Ancestry Populations. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1132799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, F.; Arnberg, F.K.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Larsson, H.; Brikell, I.; Chang, Z.; Andreassen, O.A.; Lichtenstein, P.; et al. Sex Differences in Clinically Diagnosed Psychiatric Disorders over the Lifespan: A Nationwide Register-Based Study in Sweden. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2024, 47, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; López-de-Andrés, A.; Del Barrio, J.L.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Valero-de-Bernabé, M.; Jiménez-García, R. Gender Differences in the Prevalence and Characteristics of Pain in Spain: Report from a Population-Based Study. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, E.J.; Fillingim, R.B. Sex Differences in Pain: A Brief Review of Clinical and Experimental Findings. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athnaiel, O.; Cantillo, S.; Paredes, S.; Knezevic, N.N. The Role of Sex Hormones in Pain-Related Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, J.M.; Bennett, D.L. Addressing the Gender Pain Gap. Neuron 2021, 109, 2641–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Failla, M.D.; Beach, P.A.; Atalla, S.; Dietrich, M.S.; Bruehl, S.; Cowan, R.L.; Monroe, T.B. Gender Differences in Pain Threshold, Unpleasantness, and Descending Pain Modulatory Activation Across the Adult Life Span: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Pain 2024, 25, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Enkh-Amgalan, N.; Zorigt, G.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Chen, H.-J.; Yang, H.-Y. Gender Differences and Burden of Chronic Conditions: Impact on Quality of Life among the Elderly in Taiwan. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pianigiani, T.; Perea, B.; Dilroba, A.; Fanella, A.; Milli, C.; Postiferi, S.; Rubegni, L.; Bergantini, L.; D’Alessandro, M.; Cameli, P.; et al. Uncovering Sex and Gender Differences in Sarcoidosis: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010024

Pianigiani T, Perea B, Dilroba A, Fanella A, Milli C, Postiferi S, Rubegni L, Bergantini L, D’Alessandro M, Cameli P, et al. Uncovering Sex and Gender Differences in Sarcoidosis: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010024

Chicago/Turabian StylePianigiani, Tommaso, Beatrice Perea, Akter Dilroba, Asia Fanella, Clarissa Milli, Sara Postiferi, Leonardo Rubegni, Laura Bergantini, Miriana D’Alessandro, Paolo Cameli, and et al. 2026. "Uncovering Sex and Gender Differences in Sarcoidosis: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010024

APA StylePianigiani, T., Perea, B., Dilroba, A., Fanella, A., Milli, C., Postiferi, S., Rubegni, L., Bergantini, L., D’Alessandro, M., Cameli, P., & Bargagli, E. (2026). Uncovering Sex and Gender Differences in Sarcoidosis: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010024