Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes for Women Without Male Partners Undergoing Fertility Care via Intrauterine Insemination: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Outcomes

2.3. IUI Protocol

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. IUI Outcomes

3.3. Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raja, N.S.; Russell, C.B.; Moravek, M.B. Assisted reproductive technology: Considerations for the nonheterosexual population and single parents. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddleston, A.; Ray, K.; Bacani, R.; Staggs, J.; Anderson, R.M.; Vassar, M. Inequities in Medically Assisted Reproduction: A Scoping Review. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 30, 2373–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpinello, O.J.; Jacob, M.C.; Nulsen, J.; Benadiva, C. Utilization of fertility treatment and reproductive choices by lesbian couples. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 1709–1713.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirubarajan, A.; Patel, P.; Leung, S.; Park, B.; Sierra, S. Cultural competence in fertility care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people: A systematic review of patient and provider perspectives. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG. ACOG committee opinion no. 749: Marriage and family building equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and gender nonconforming individuals. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Access to fertility treatment irrespective of marital status, sexual orientation, or gender identity: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, I.; Balet, R.; Grudzinskas, J.G. Intrauterine donor insemination in single women and lesbian couples: A comparative study of pregnancy rates. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 15, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johal, J.K.; Gardner, R.M.; Vaughn, S.J.; Jaswa, E.G.; Hedlin, H.; Aghajanova, L. Pregnancy success rates for lesbian women undergoing intrauterine insemination. F S Rep. 2021, 2, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrande, T.; Kristjansdottir, B.H.; Tsiartas, P.; Hadziosmanovic, N.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A. Live birth, cumulative live birth and perinatal outcome following assisted reproductive treatments using donor sperm in single women vs. women in lesbian couples: A prospective controlled cohort study. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordqvist, S.; Sydsjö, G.; Lampic, C.; Åkerud, H.; Elenis, E.; Skoog, S.A. Sexual orientation of women does not affect outcome of fertility treatment with donated sperm. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; McCracken, M.; Dominguez, L.V.; Zhang, A.; Johal, J.; Aghajanova, L. The impact of estradiol supplementation on endometrial thickness and intrauterine insemination outcomes. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 24, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicchieri, F.; Silva, A.B.; Silva, A.C.J.S.R.E.; Navarro, P.A.A.S.; Ferriani, R.A.; Reis, R.M.D. Prognostic factors in intrauterine insemination cycles. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2018, 22, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starosta, A.; Gordon, C.E.; Hornstein, M.D. Predictive factors for intrauterine insemination outcomes: A review. Fertil. Res. Pract. 2020, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malchau, S.S.; Loft, A.; Henningsen, A.K.; Nyboe Andersen, A.; Pinborg, A. Perinatal outcomes in 6,338 singletons born after intrauterine insemination in Denmark, 2007 to 2012: The influence of ovarian stimulation. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 1110–1116.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, L.; Cai, C.; Yan, G.; Sun, H. Clinical and neonatal outcomes of intrauterine insemination with frozen donor sperm. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2018, 64, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, C.P.; Marconi, N.; McLernon, D.J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Maheshwari, A. Outcomes of pregnancies using donor sperm compared with those using partner sperm: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2021, 27, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diego, D.; Medline, A.; Shandley, L.M.; Kawwass, J.F.; Hipp, H.S. Donor sperm recipients: Fertility treatments, trends, and pregnancy outcomes. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Comadran, M.; Urresta Avila, J.; Saavedra Tascon, A.; Jimenez, R.; Sola, I.; Brassesco, M.; Carreras, R.; Checa, M.A. The impact of donor insemination on the risk of preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 182, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.N.; Walker, M.; Tessier, J.L.; Millar, K.G. Increased incidence of preeclampsia in women conceiving by intrauterine insemination with donor versus partner sperm for treatment of primary infertility. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 177, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990–2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 2278–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, H.A.; Ashmead, R.; Farmer, A.; Kim, Y.H.; Shellhaas, C.; Oza-Frank, R.; Jackson, R.D.; Costantine, M.M.; Lynch, C.D. Association of Prepregnancy Body Mass Index with Risk of Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2218986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Women Without Male Partners (n = 149 *) | Reference: Women with Male Partners (n = 2265 *) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42 [37, 44] | 38 [35, 41] | <0.0001 |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 [21.1, 31.1] | 24.2 [21.8, 27.5] | 0.35 |

| Cycle type | <0.0001 | ||

| Clomiphene citrate | 41 (27.5) | 883 (39.0) | |

| Letrozole | 42 (28.2) | 919 (40.6) | |

| Natural cycle | 49 (32.9) | 270 (11.9) | |

| Gonadotropins | 17 (11.4) | 182 (8.0) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||

| Caucasian | 26 (50.0) | 236 (26.9) | |

| Asian American | 9 (17.3) | 465 (53.0) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 8 (15.4) | 60 (6.8) | |

| African American | 3 (5.8) | 13 (1.5) | |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (1.9) | 6 (0.7) | |

| Other | 3 (5.8) | 51 (5.8) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3.8) | 47 (5.4) | |

| Infertility Diagnosis | |||

| Male factor | 0 (0.0) | 162 (18.5) | 0.001 |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 7 (13.5) | 229 (26.1) | 0.04 |

| PCOS | 0 (0.0) | 62 (7.1) | 0.05 |

| Ovulatory dysfunction | 1 (1.9) | 84 (9.6) | 0.08 |

| Endometriosis | 0 (0.0) | 30 (3.4) | 0.41 |

| Uterine factor | 1 (1.9) | 23 (2.6) | 1.00 |

| Tubal disease | 0 (0.0) | 21 (2.4) | 0.63 |

| Recurrent pregnancy loss | 0 (0.0) | 32 (3.6) | 0.25 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.7) | 1.00 |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1.00 |

| Unexplained | 0 (0.0) | 289 (33.0) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline antral follicle count (n) | 9 [6, 15] | 11 [5, 17] | 0.12 |

| Cycle day at trigger | 12 [11, 13] | 12 [11, 14] | 0.39 |

| Endometrial thickness at trigger (mm) | 7.8 [7.1, 8.9] | 8.0 [7.0, 9.0] | 0.59 |

| Presence of trilaminar pattern at trigger | 102 [82.9] | 1593 [79.1] | 0.30 |

| Size of leading follicle at trigger (mm) | 19 [17, 21] | 19 [17, 21] | 0.55 |

| Sperm concentration (millions/mL) | 45.4 [32.0, 71.2] | 46.3 [19.8, 100.1] | 0.90 |

| Percent motility (%) | 50 [39, 58] | 85 [70, 92] | <0.0001 |

| Total motile sperm count (millions) | 10.4 [6.8, 17.2] | 18.5 [6.5, 45.2] | <0.0001 |

| Women Without Male Partners (n = 149) | Reference: Women with Male Partners (n = 2265) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive βhCG | 18 (12.1) | 316 (14.9) | 0.52 |

| Clinical pregnancy | 17 (11.4) | 282 (12.5) | 0.56 |

| Biochemical miscarriage | 1(5.6) | 28(8.9) | 0.30 |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.3) | 1.00 |

| Clinical miscarriage | 5(27.8) | 94(29.8) | 0.50 |

| Live birth | 12 (8.1) | 186 (8.2) | 0.95 |

| Multiple pregnancy (twins) | 1(5.9) | 8(2.8) | 0.23 |

| Number of IUI cycles completed | 2 [1, 4] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.05 |

| Number of IUI cycles until pregnancy | 2 [1, 5] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.07 |

| Number of IUI cycles until live birth | 2 [2, 4] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.26 |

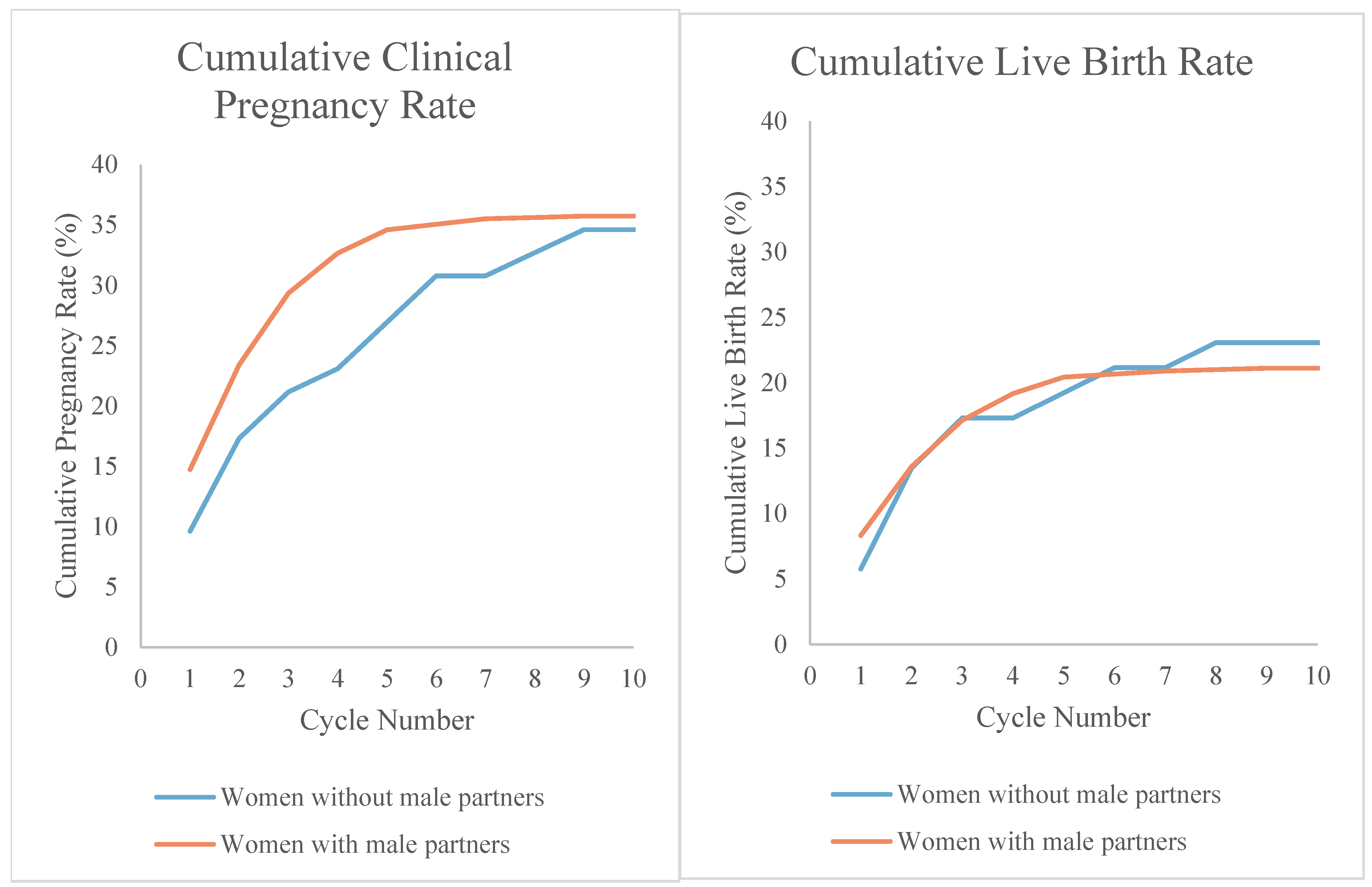

| Cumulative pregnancy rate: | 11 (21.2) | 257 (29.3) | 0.21 |

| Cycle 1 | 9.6 | 14.8 | 0.30 |

| Cycle 2 | 17.3 | 23.3 | 0.31 |

| Cycle 3 | 21.2 | 29.3 | 0.21 |

| Cycle 4 | 23.1 | 32.6 | 0.15 |

| Cycle 5 | 26.9 | 34.6 | 0.26 |

| Cumulative live birth rate: | |||

| Cycle 1 | 5.8 | 8.3 | 0.79 |

| Cycle 2 | 13.5 | 13.6 | 0.99 |

| Cycle 3 | 17.3 | 17.1 | 0.97 |

| Cycle 4 | 17.3 | 19.2 | 0.74 |

| Cycle 5 | 19.2 | 20.4 | 0.84 |

| Pregnancy Outcomes | Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy rate per cycle a | 1.11 | 0.61, 2.02 | 0.73 |

| Clinical miscarriage b | 0.75 | 0.15, 3.76 | 0.73 |

| Live birth c | 1.47 | 0.74, 3.09 | 0.31 |

| Rate Ratio (RR) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

| Cumulative pregnancy rate | 0.96 | 0.60, 1.55 | 0.87 |

| Neonatal Outcomes d | Adjusted Mean Difference | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

| Gestational age at delivery (days) | −0.9 | −7.6, 5.9 | 0.80 |

| Birthweight (grams) | 148.0 | −190.9, 487.0 | 0.39 |

| Women Without Male Partners (n = 18) | Reference: Women with Male Partners (n = 316) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy complications | |||

| Any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | 3 (16.7) | 23 (7.3) | 0.16 |

| Gestational hypertension | 0 (0.0) | 9 (2.9) | 0.27 |

| Pre-eclampsia without severe features | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.2) | 0.19 |

| Pre-eclampsia with severe features | 2 (11.1) | 6 (1.9) | 0.06 |

| Eclampsia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | -- |

| HELLP syndrome | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.05 |

| Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Placenta disorder (abruption, previa, accreta spectrum) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (1.0) | 0.20 |

| Gestational diabetes | 2 (11.1) | 34 (10.8) | 1.00 |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 14 (4.4) | 1.00 |

| Cesarean section | 4 (22.2) | 56 (17.8) | 0.54 |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||

| Gestational age at delivery (days) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 269.5 ± 10.3 | 270.9 ± 13.5 | 0.67 |

| Median [IQR] | 273 [262, 275] | 274 [266, 279] | 0.31 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | 2 (16.7) | 15 (8.1) | 0.27 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3200 [2530, 3600] | 3140 [2807, 3445] | 0.69 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 2 (16.7) | 18 (9.7) | 0.35 |

| Very low birth weight (<1500 g) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 1.00 |

| Neonate’s sex | 0.79 | ||

| Female | 6 (50.0) | 92 (49.5) | |

| Male | 5 (41.7) | 83 (44.6) | |

| Unknown | 1 (8.3) | 11 (5.9) | |

| Apgar score at 1 min | 8 [8, 9] | 8 [8, 9] | 0.25 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | 9 [9, 9] | 9 [9, 9] | 0.94 |

| NICU admissions | 0 (0.0) | 20 (10.8) | 0.61 |

| Neonatal morbidity | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| Congenital anomaly | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.3) | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.Y.; McCracken, M.; Zhang, A.; Dominguez, L.V.; Aghajanova, L. Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes for Women Without Male Partners Undergoing Fertility Care via Intrauterine Insemination: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120589

Zhang WY, McCracken M, Zhang A, Dominguez LV, Aghajanova L. Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes for Women Without Male Partners Undergoing Fertility Care via Intrauterine Insemination: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120589

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wendy Y., Megan McCracken, Amy Zhang, Lisandra Veliz Dominguez, and Lusine Aghajanova. 2025. "Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes for Women Without Male Partners Undergoing Fertility Care via Intrauterine Insemination: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120589

APA StyleZhang, W. Y., McCracken, M., Zhang, A., Dominguez, L. V., & Aghajanova, L. (2025). Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes for Women Without Male Partners Undergoing Fertility Care via Intrauterine Insemination: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120589