Small Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Cisplatin-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells Increase Lactate Secretion and Alter Metabolic Pathways in Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Cell Culture and Conditioned Media Harvest from CELLine™ AD1000 Bioreactor

2.3. sEV Isolation

2.4. Nanoparticle Tracking Assay (NTA)

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.6. ExoView Platform

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Fractionation

2.9. Mass Spectrometry

2.10. Data Processing

2.11. Bioinformatics and Network Analysis

2.12. Kaplan–Meier Survival Analysis

2.13. NIR-AZA 1 Fluorophore sEV Labelling and Uptake

2.14. Lactate Secretion

2.15. Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate Assay

2.16. Tubule Formation Assay

2.17. Wound Healing Assay

2.18. Cell Proliferation

2.19. Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) Determination

2.20. Cisplatin Toxicity Assay

2.21. Statistics

3. Results

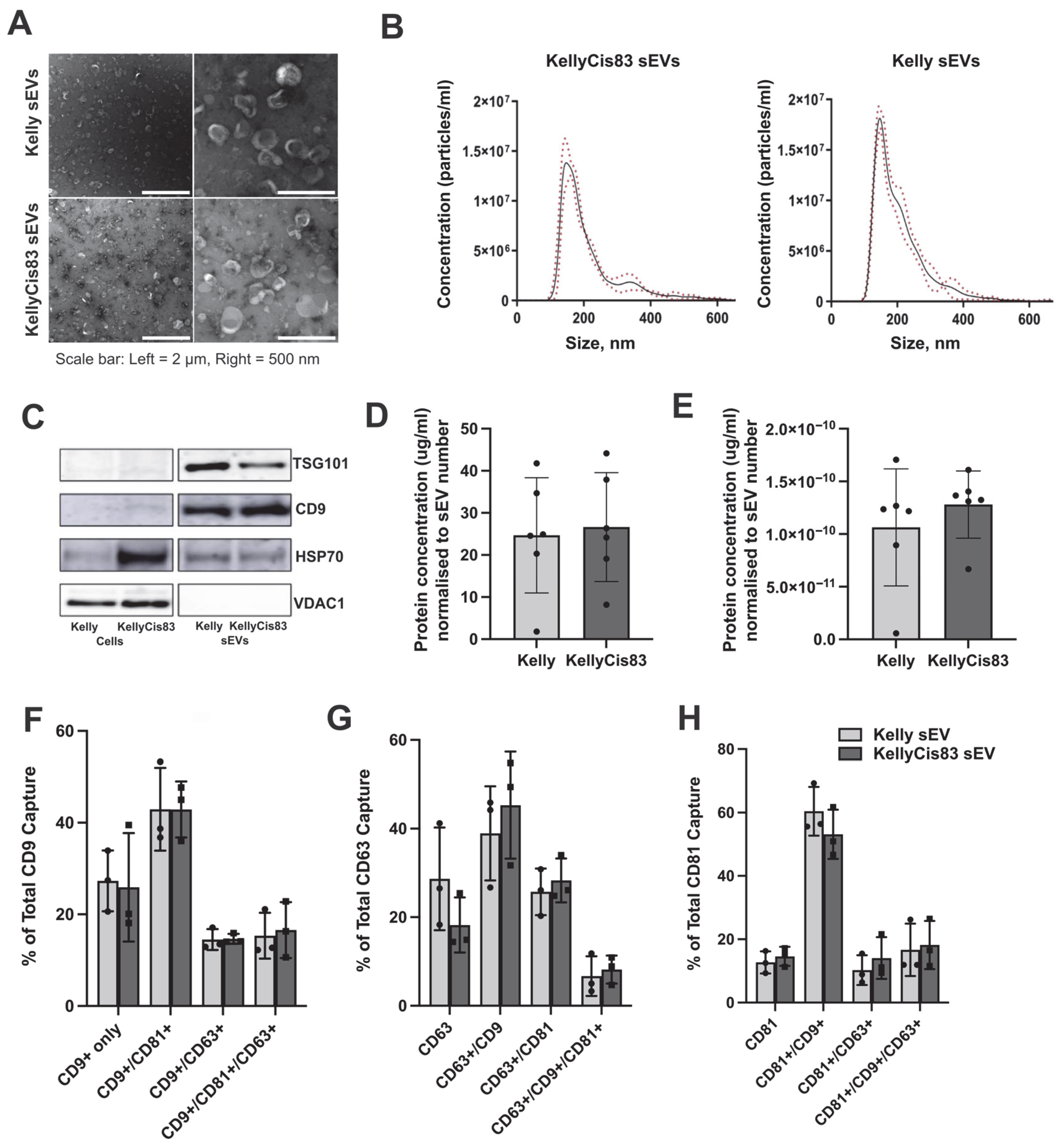

3.1. Purification and Physical Characterisation of sEVs Derived from Kelly and KellyCis83 NB Cells

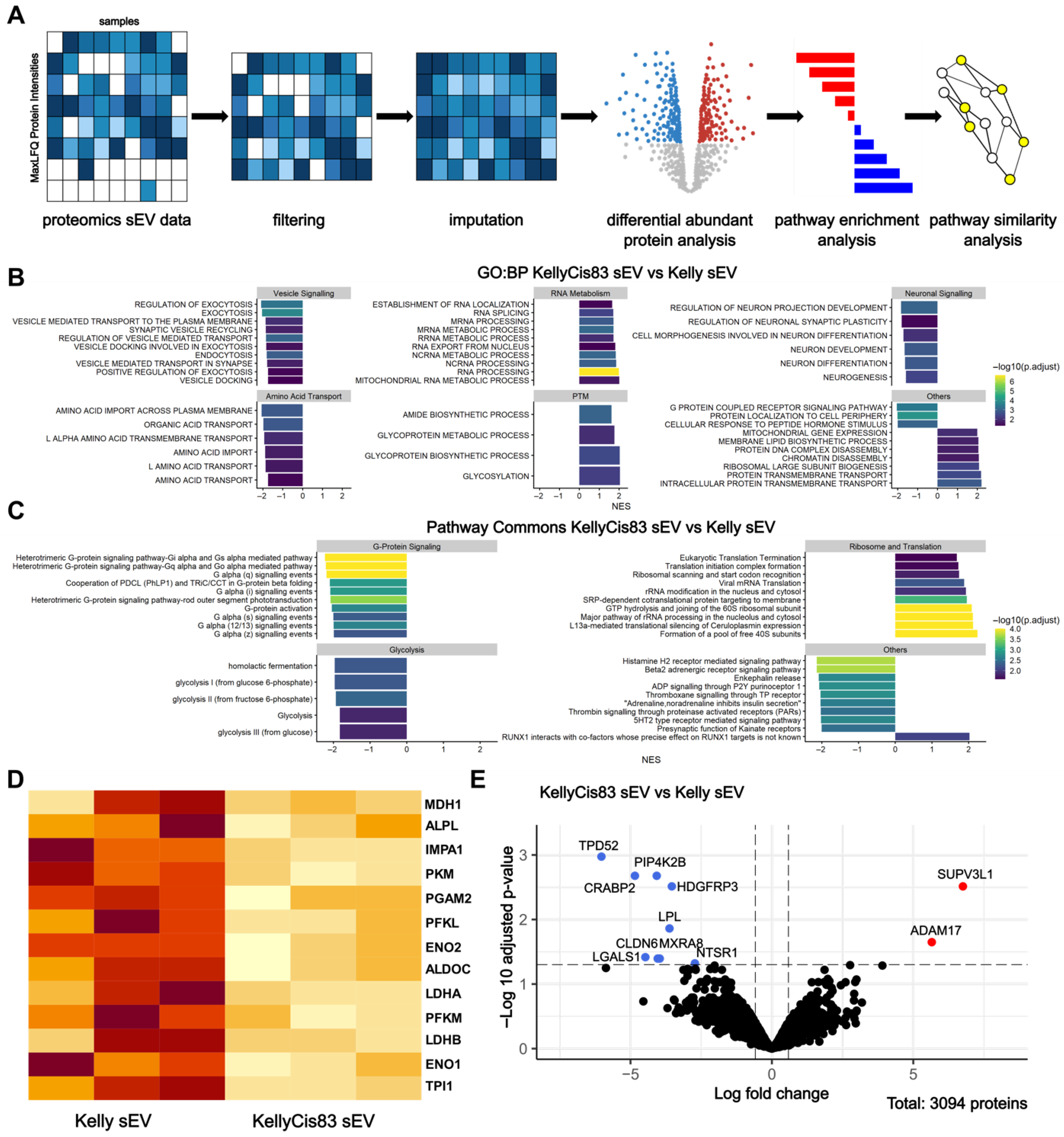

3.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis of sEV Proteome Identifies Metabolism as a Key Dysregulated Pathway in KellyCis83 sEVs

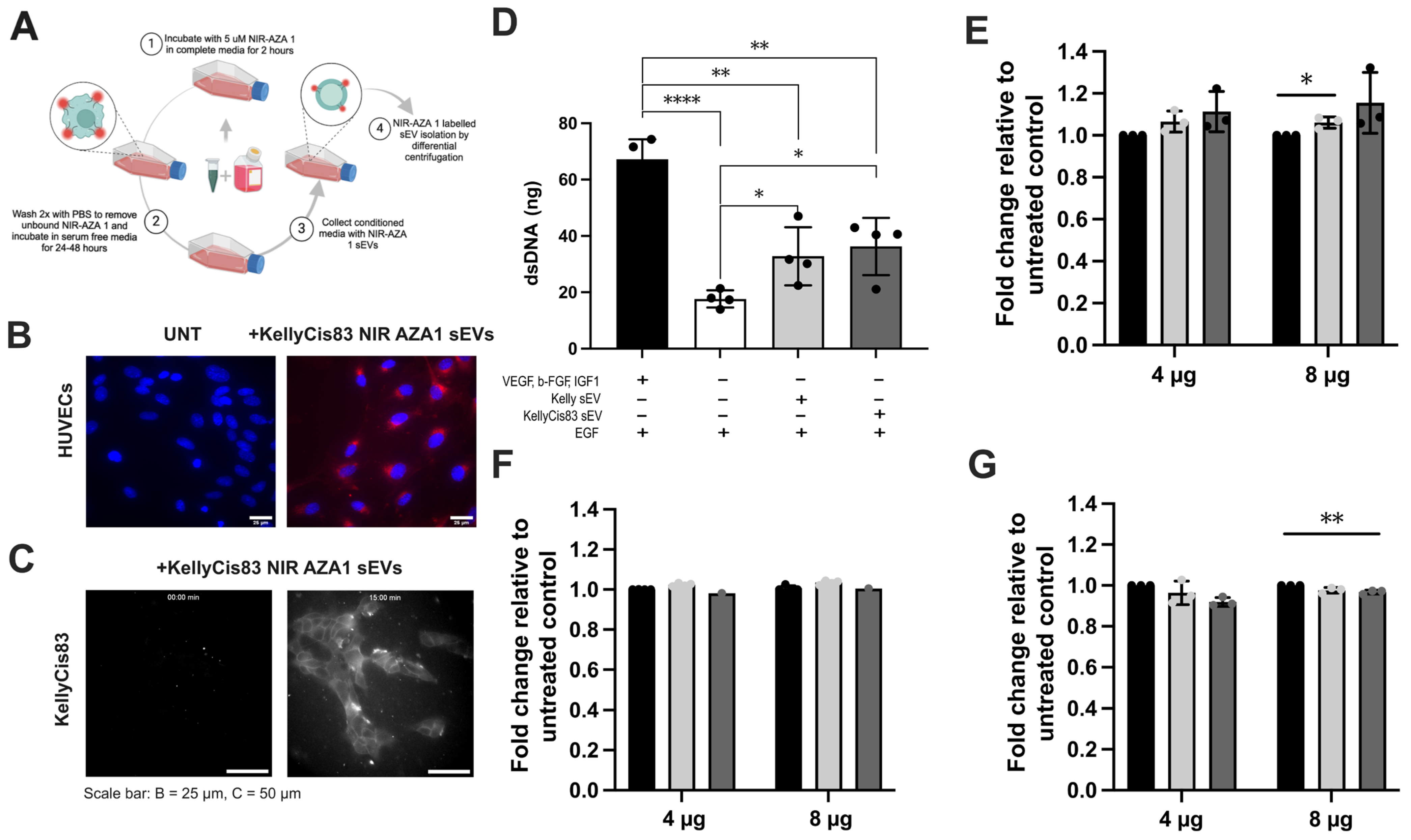

3.3. KellyCis83 sEVs Are Internalised by Cancerous and Non-Cancerous Cells

3.4. Cell Proliferation Demonstrated a Dose-Dependent Response to sEV Treatment

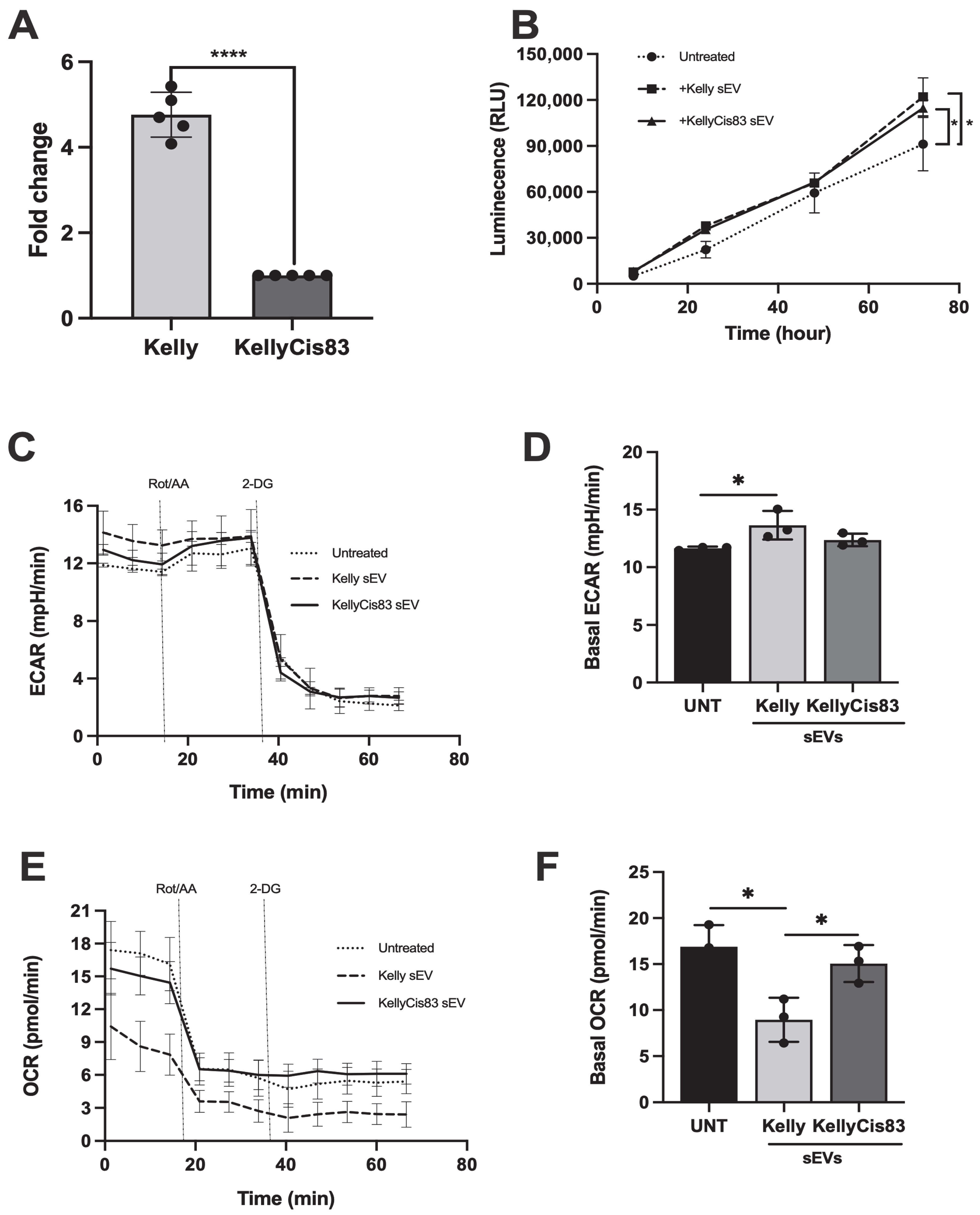

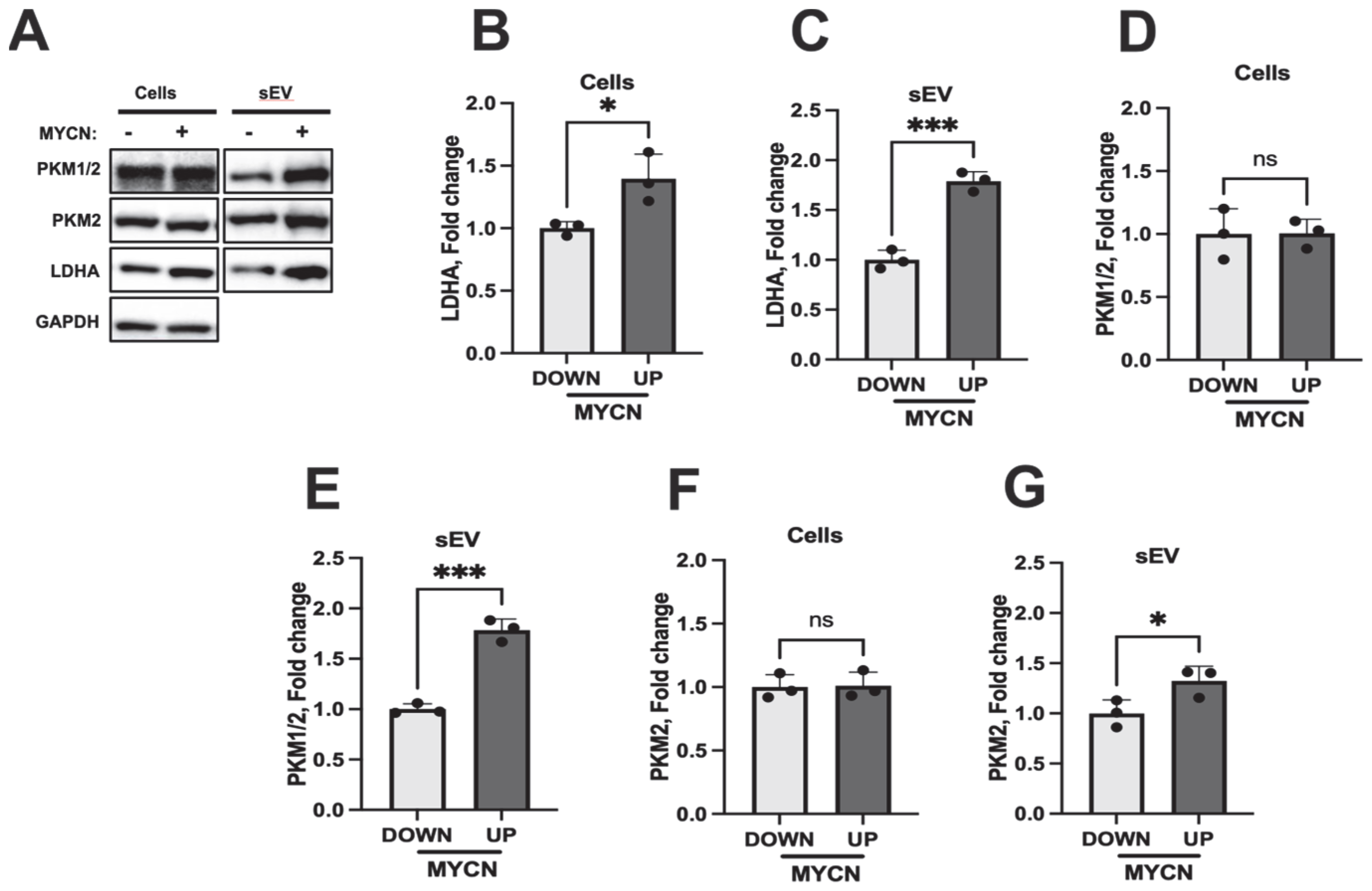

3.5. sEVs Secreted by NB Cells Increased Lactate Secretion and Altered Metabolic Pathways in HUVECs

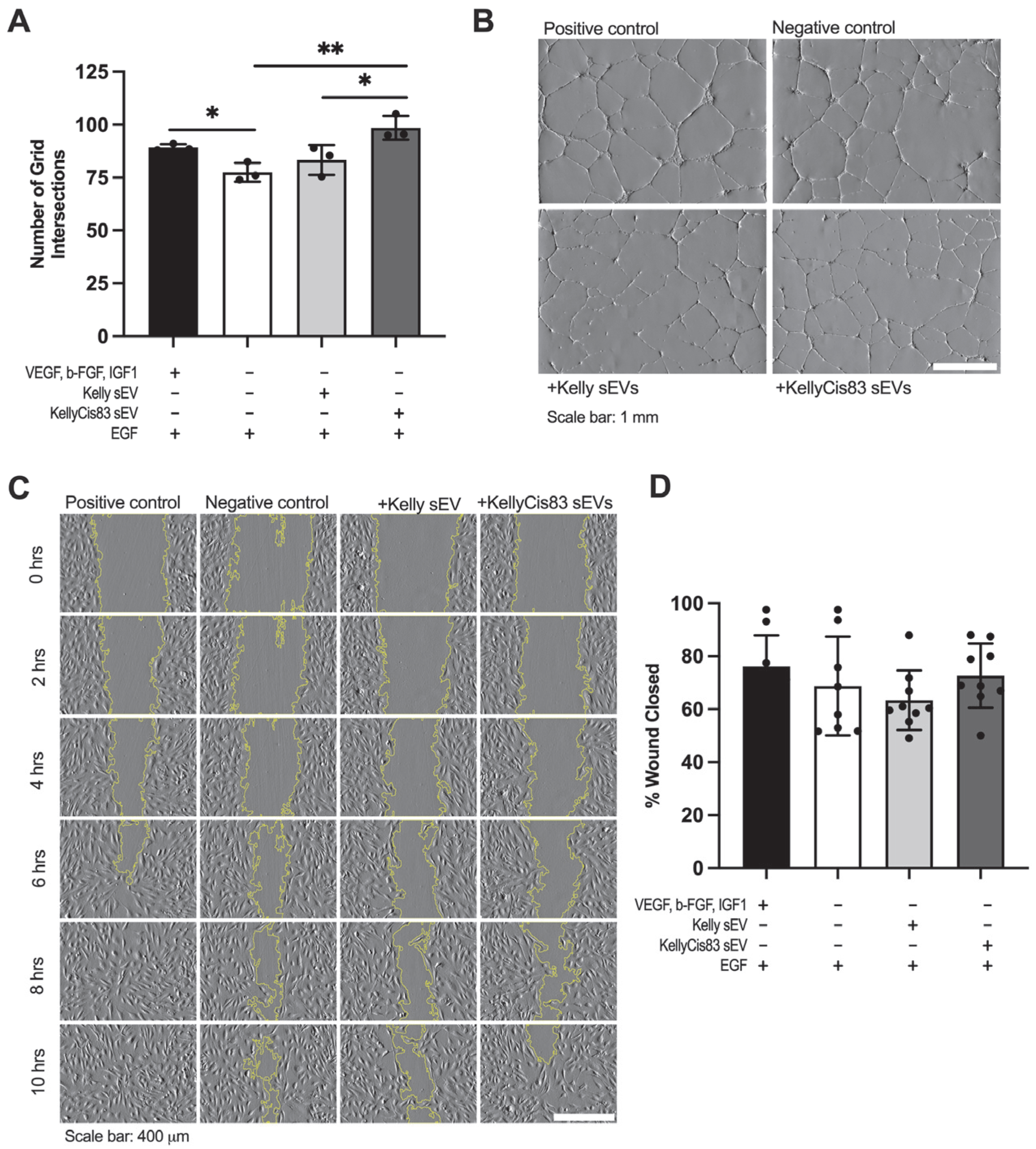

3.6. KellyCis83 sEVs Increased Anchorage-Dependent Differentiation of HUVECs

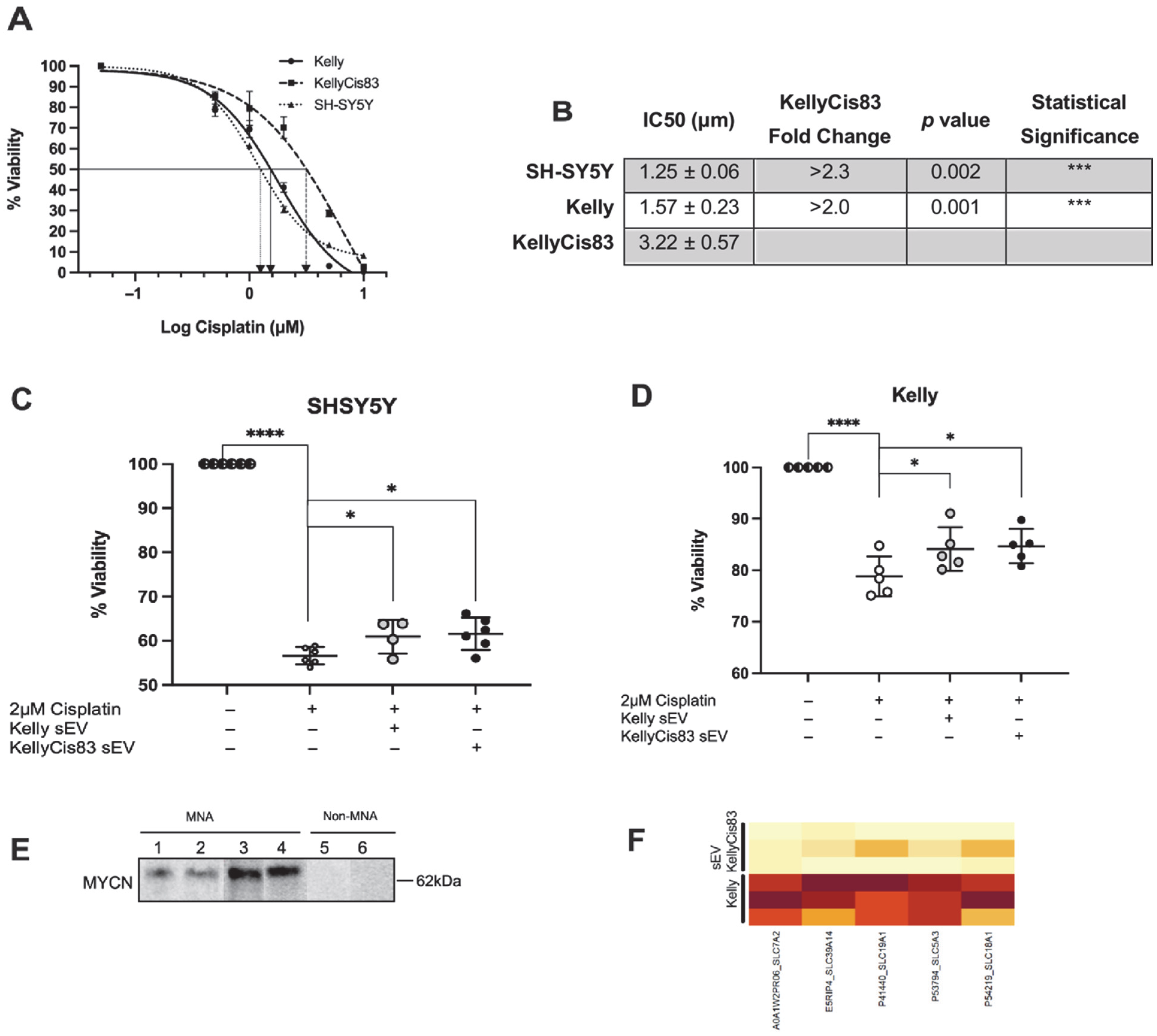

3.7. Transfer of Chemoresistance via KellyCis83 sEVs

3.8. Clinical Relevance of Proteins That Contributed to Significant Glycolysis Enrichment in Neuroblastoma

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Irwin, M.S.; Naranjo, A.; Zhang, F.F.; Cohn, S.L.; London, W.B.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Ramirez, N.C.; Pfau, R.; Reshmi, S.; Wagner, E.; et al. Revised Neuroblastoma Risk Classification System: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3229–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, C.U.; Shohet, J.M. Neuroblastoma: Molecular Pathogenesis and Therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, E.; Bayeva, N.; Stallings, R.L.; Piskareva, O. Neuroblastoma. In Epigenetic Cancer Therapy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.H.; Federico, S.M.; London, W.B.; Naranjo, A.; Irwin, M.S.; Volchenboum, S.L.; Cohn, S.L. Tailoring Therapy for Children With Neuroblastoma on the Basis of Risk Group Classification: Past, Present, and Future. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2020, 4, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willms, E.; Cabañas, C.; Mäger, I.; Wood, M.J.A.; Vader, P. Extracellular Vesicle Heterogeneity: Subpopulations, Isolation Techniques, and Diverse Functions in Cancer Progression. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; Roy, S.; Saha, P.; Chatterjee, N.; Bishayee, A. Trends in research on exosomes in cancer progression and anticancer therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, N.; Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; Pang, B.; Dong, X.; Li, Y.; Fan, T. The Emerging Role of Exosomes in Cancer Chemoresistance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 737962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, E.S.; Ginini, L.; Gil, Z. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Metabolic Reprogramming of the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells 2022, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, K.K.W.; Cho, W.C.S. Exosome secretion from hypoxic cancer cells reshapes the tumor microenvironment and mediates drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 2022, 5, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, P.; Liem, M.; Ozcitti, C.; Adda, C.G.; Ang, C.; Mathivanan, S. Exosomes from N-Myc amplified neuroblastoma cells induce migration and confer chemoresistance to non-N-Myc amplified cells: Implications of intra-tumour heterogeneity. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1597614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challagundla, K.B.; Wise, P.M.; Neviani, P.; Chava, H.; Murtadha, M.; Xu, T.; Kennedy, R.; Ivan, C.; Zhang, X.; Vannini, I.; et al. Exosome-Mediated Transfer of microRNAs Within the Tumor Microenvironment and Neuroblastoma Resistance to Chemotherapy. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, C.A.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Spiegelman, V.S.; Sundstrom, J.; Wang, H.-G. Chemotherapy-induced small extracellular vesicles prime the pre-metastatic niche to accelerate neuroblastoma metastasis. Genes. Dis. 2024, 11, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Yerneni, S.S.; Razzo, B.M.; Whiteside, T.L. Exosomes from HNSCC Promote Angiogenesis through Reprogramming of Endothelial Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1798–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Vasaikar, S.; Eskaros, A.; Kim, Y.; Lewis, J.S.; Zhang, B.; Zijlstra, A.; Weaver, A.M. EPHB2 carried on small extracellular vesicles induces tumor angiogenesis via activation of ephrin reverse signaling. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 132447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Hou, D.; Huang, Q.; Zhan, W.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; You, R.; Xie, J.; Chen, P.; et al. Exosomes derived from acute myeloid leukemia cells promote chemoresistance by enhancing glycolysis-mediated vascular remodeling. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 10602–10614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, A.; Nagayama, S.; Sumazaki, M.; Konishi, M.; Fujii, R.; Saichi, N.; Muraoka, S.; Saigusa, D.; Shimada, H.; Sakai, Y.; et al. Colorectal Cancer–Derived CAT1-Positive Extracellular Vesicles Alter Nitric Oxide Metabolism in Endothelial Cells and Promote Angiogenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskareva, O.; Harvey, H.; Nolan, J.; Conlon, R.; Alcock, L.; Buckley, P.; Dowling, P.; Henry, M.; O’Sullivan, F.; Bray, I.; et al. The development of cisplatin resistance in neuroblastoma is accompanied by epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2015, 364, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Devis-Jauregui, L.; Struck, R.; Boloix, A.; Gallagher, C.; Gavin, C.; Cottone, F.; Fernandez, A.S.; Madden, S.; Roma, J.; et al. In vivo cisplatin-resistant neuroblastoma metastatic model reveals tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4 (TNFRSF4) as an independent prognostic factor of survival in neuroblastoma. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, C.; Nolan, J.; Conlon, R.; Deneweth, L.; Gallagher, C.; Tan, Y.; Cavanagh, B.; Asraf, A.; Harvey, H.; Miller-Delaney, S.; et al. A physiologically relevant 3D collagen-based scaffold–neuroblastoma cell system exhibits chemosensitivity similar to orthotopic xenograft models. Acta Biomater. 2018, 70, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, 12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, W.; Stöhr, M.; Schürmann, J.; Wenzel, A.; Löhr, A.; Schwab, M. Conditional expression of N-myc in human neuroblastoma cells increases expression of α-prothymosin and ornithine decarboxylase and accelerates progression into S-phase early after mitogenic stimulation of quiescent cells. Oncogene 1996, 13, 803–812. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, E.; Matthias, P.; Müller, M.M.; Schaffner, W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Tomas, H.; Havli, J.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2856–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodchenkov, I.; Babur, O.; Luna, A.; Aksoy, B.A.; Wong, J.V.; Fong, D.; Franz, M.; Siper, M.C.; Cheung, M.; Wrana, M.; et al. Pathway Commons 2019 Update: Integration, analysis and exploration of pathway data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D489–D497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G. Gene Ontology Semantic Similarity Analysis Using GOSemSim; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R2 Database. Genomic Analysis and Visualization Platform. The Department of Human Genetics in the Amsterdam Medical Centre (AMC). Available online: https://hgserver1.amc.nl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi?open_page=login#loginsection (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Hertwig, F.; Thierry-Mieg, J.; Zhang, W.; Thierry-Mieg, D.; Wang, J.; Furlanello, C.; Devanarayan, V.; Cheng, J.; et al. Comparison of RNA-seq and microarray-based models for clinical endpoint prediction. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monopoli, M.P.; Zendrini, A.; Wu, D.; Cheung, S.; Sampedro, G.; Ffrench, B.; Nolan, J.; Piskareva, O.; Stalings, R.L.; Ducoli, S.; et al. Endogenous exosome labelling with an amphiphilic NIR-fluorescent probe. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 7219–7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, N.S.M.; van der Kooi, E.J.; Enciso-Martinez, A.; Lozano-Andrés, E.; Otto, C.; Wauben, M.H.M.; Tytgat, G.A.M. Extracellular Vesicles: A New Source of Biomarkers in Pediatric Solid Tumors? A Systematic Review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 887210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, J.; Feghhi, M.; Etemadi, T. A review on exosomes application in clinical trials: Perspective, questions, and challenges. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetler, D.J.; Di Florio, D.N.; Bruno, K.A.; Ikezu, T.; March, K.L.; Cooper, L.T.; Wolfram, J.; Fairweather, D. Extracellular vesicles as personalized medicine. Mol. Asp. Med. 2023, 91, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, S.; Umehara, S.; Gerbing, R.B.; Stram, D.O.; Brodeur, G.M.; Seeger, R.C.; Lukens, J.N.; Matthay, K.K.; Shimada, H. Histopathology (International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification) and MYCN Status in Patients with Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors A Report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Cancer 2001, 92, 2699–2708. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1097-0142(20011115)92:10%3C2699::AID-CNCR1624%3E3.0.CO;2-A/pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Weiss, W.A. Neuroblastoma and MYCN. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a014415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Mann, M.; Naranjo, A.H.; Van Ryn, C.; Bagatell, R.; Matthay, K.K.; London, W.B.; Irwin, M.S.; Shimada, H.; et al. Association of MYCN copy number with clinical features, tumor biology, and outcomes in neuroblastoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2017, 123, 4224–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortolici, F.; Vumbaca, S.; Incocciati, B.; Dayal, R.; Aquilano, K.; Giovanetti, A.; Rufini, S. Ionizing Radiation-Induced Extracellular Vesicle Release Promotes AKT-Associated Survival Response in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, D.; Gaude, E.; Orso, G.; Giordano, C.; Guzzo, G.; Rasola, A.; Ragazzi, E.; Caparrotta, L.; Frezza, C.; Montopoli, M. Inhibition of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase sensitizes cisplatin-resistant cells to death. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 30102–30114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colla, R.; Izzotti, A.; De Ciucis, C.; Fenoglio, D.; Ravera, S.; Speciale, A.; Ricciarelli, R.; Furfaro, A.L.; Pulliero, A.; Passalacqua, M.; et al. Glutathione-mediated antioxidant response and aerobic metabolism: Two crucial factors involved in determining the multi-drug resistance of high-risk neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 70715–70737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbats, M.A.; Giacomini, I.; Prayer-Galetti, T.; Montopoli, M. Metabolic Plasticity in Chemotherapy Resistance. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zong, X. Metabolic Symbiosis in Chemoresistance: Refocusing the Role of Aerobic Glycolysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakaneli, A.; Carregari, V.C.; Morini, M.; Eva, A.; Cangemi, G.; Chayka, O.; Makarov, E.; Bibbò, S.; Capone, E.; Sala, G.; et al. MYC regulates metabolism through vesicular transfer of glycolytic kinases. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sheng, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Han, J. Ovarian cancer derived PKR1 positive exosomes promote angiogenesis by promoting migration and tube formation in vitro. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ma, N.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, B. Exosomes derived from 5-fluorouracil-resistant colon cancer cells are enriched in GDF15 and can promote angiogenesis. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 7116–7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan-Qing, W.; Xiao, Y.; Shi-Yi, L.; Meng-Qin, Y.; Shu, X.; Dong-Yong, Y.; Ya-Jing, Z.; Yan-Xiang, C. Exosomes secreted by chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells promote angiogenesis. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, C.; Rani, S.; O’Brien, K.; O’Neill, A.; Prencipe, M.; Sheikh, R.; Webb, G.; McDermott, R.; Watson, W.; Crown, J.; et al. Docetaxel-Resistance in Prostate Cancer: Evaluating Associated Phenotypic Changes and Potential for Resistance Transfer via Exosomes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Vo, K.T.; London, W.B.; Fischer, M.; Ambros, P.F.; Nakagawara, A.; Brodeur, G.M.; Matthay, K.K.; DuBois, S.G. Identification of patient subgroups with markedly disparate rates of MYCN amplification in neuroblastoma: A report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group project. Cancer 2016, 122, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panachan, J.; Rojsirikulchai, N.; Pongsakul, N.; Khowawisetsut, L.; Pongphitcha, P.; Siriboonpiputtana, T.; Chareonsirisuthigul, T.; Phornsarayuth, P.; Klinkulab, N.; Jinawath, N.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle-Based Method for Detecting MYCN Amplification Status of Pediatric Neuroblastoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, B.H.; Hald, Ø.H.; Utnes, P.; Roth, S.A.; Løkke, C.; Flægstad, T.; Einvik, C. Exosome-like Extracellular Vesicles from MYCN-amplified Neuroblastoma Cells Contain Oncogenic miRNAs. Anticancer. Res. 2015, 35, 2521–2530. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25964525 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, M.; Rani, R. Role of LDH in tumor glycolysis: Regulation of LDHA by small molecules for cancer therapeutics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 87, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorneburg, C.; Fischer, M.; Barth, T.F.; Mueller-Klieser, W.; Hero, B.; Gecht, J.; Carter, D.R.; de Preter, K.; Mayer, B.; Christner, L.; et al. LDHA in Neuroblastoma Is Associated with Poor Outcome and Its Depletion Decreases Neuroblastoma Growth Independent of Aerobic Glycolysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 5772–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morini, M.; Raggi, F.; Bartolucci, M.; Petretto, A.; Ardito, M.; Rossi, C.; Segalerba, D.; Garaventa, A.; Eva, A.; Cangelosi, D.; et al. Plasma-Derived Exosome Proteins as Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers in Neuroblastoma Patients. Cells 2023, 12, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhto, N.; Pongphitcha, P.; Jinawath, N.; Hongeng, S.; Chutipongtanate, S. Extracellular Vesicles for Childhood Cancer Liquid Biopsy. Cancers 2024, 16, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Hu, S.; Zhang, L.; Xin, J.; Sun, C.; Wang, L.; Ding, K.; Wang, B. Tumor circulome in the liquid biopsies for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4544–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, M.; Cangelosi, D.; Segalerba, D.; Marimpietri, D.; Raggi, F.; Castellano, A.; Fruci, D.; Font de Mora, J.; Cañete, A.; Yáñez, Y.; et al. Exosomal microRNAs from Longitudinal Liquid Biopsies for the Prediction of Response to Induction Chemotherapy in High-Risk Neuroblastoma Patients: A Proof of Concept SIOPEN Study. Cancers 2019, 11, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Supplement | Concentration | GF+ | GF− |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foetal calf serum | 0.02 mL/mL | + | + |

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) | 5 ng/mL | + | + |

| Ascorbic acid | 1 μg/mL | + | + |

| Heparin | 22.5 μg/mL | + | + |

| Hydrocortisone | 0.2 μg/mL | + | + |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) | 10 ng/mL | + | - |

| Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) | 20 ng/mL | + | - |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor 165 (VEGF) | 0.5 ng/mL | + | - |

| ID | Full Name | EFS, p-Value | Expression * | OS, p-Value | Expression | Correlation with MYCN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r-Value | p-Value | ||||||

| ALDOC | Aldolase C | 2.12 × 10−10 | ⇓ | 1.95 × 10−18 | ⇓ | −0.521 | 4.84 × 10−36 |

| ALPL | Alkaline phosphatase | 2.40 × 10−5 | ⇑ | 1.17 × 10−5 | ⇑ | NS | |

| ENO1 | Enolase 1 | 4.41 × 10−10 | ⇑ | 1.83 × 10−11 | ⇑ | 0.314 | 6.89 × 10−13 |

| ENO2 | Enolase 2 | 1.47 × 10−10 | ⇓ | 3.12 × 10−18 | ⇓ | −0.321 | 1.95 × 10−13 |

| IMPA1 | Inositol(myo)-1(or 4)-monophosphatase 1 | 0.049 | ⇑ | NS | −0.275 | 4.15 × 10−10 | |

| LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A | 8.35 × 10−18 | ⇑ | 3.43 × 10−23 | ⇑ | 0.420 | 1.08 × 10−22 |

| LDHB | Lactate dehydrogenase B | 1.05 × 10−16 | ⇑ | 1.32 × 10−26 | ⇑ | 0.708 | 4.73 × 10−77 |

| MDH1 | Malate dehydrogenase 1 | 0.052 | ⇑ | 3.58 × 10−5 | ⇑ | 0.088 | 0.049 |

| PFKL | Phosphofructokinase 1(liver) | 4.77 × 10−5 | ⇓ | 6.03 × 10−7 | ⇓ | NS | |

| PFKM | Phosphofructokinase (muscle) | 5.32 × 10−7 | ⇑ | 3.34 × 10−11 | ⇑ | 0.557 | 6.67 × 10−42 |

| PGAM2 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 | 1.35 × 10−3 | ⇓ | 2.93 × 10−4 | ⇓ | −0.244 | 3.72 × 10−8 |

| PKM | Pyruvate kinase | 1.85 × 10−10 | ⇑ | 4.62 × 10−12 | ⇑ | 0.299 | 1.02 × 10−11 |

| TPI1 | Triosephosphate isomerase 1 | 1.73 × 10−11 | ⇑ | 1.41 × 10−10 | ⇑ | 0.252 | 1.18 × 10−8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frawley, T.; Ma, L.; Arifin, M.Z.; Wu, D.; Scott, A.; Cavanagh, B.; O’Shea, D.F.; Zhernovkov, V.; Liu, M.; Monopoli, M.P.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Cisplatin-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells Increase Lactate Secretion and Alter Metabolic Pathways in Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs). J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120584

Frawley T, Ma L, Arifin MZ, Wu D, Scott A, Cavanagh B, O’Shea DF, Zhernovkov V, Liu M, Monopoli MP, et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Cisplatin-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells Increase Lactate Secretion and Alter Metabolic Pathways in Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs). Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120584

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrawley, Thomas, Lin Ma, Muhammad Zainul Arifin, Dan Wu, Alysia Scott, Brenton Cavanagh, Donal F. O’Shea, Vadim Zhernovkov, Mi Liu, Marco P. Monopoli, and et al. 2025. "Small Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Cisplatin-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells Increase Lactate Secretion and Alter Metabolic Pathways in Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs)" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120584

APA StyleFrawley, T., Ma, L., Arifin, M. Z., Wu, D., Scott, A., Cavanagh, B., O’Shea, D. F., Zhernovkov, V., Liu, M., Monopoli, M. P., & Piskareva, O. (2025). Small Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Cisplatin-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells Increase Lactate Secretion and Alter Metabolic Pathways in Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs). Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120584