Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome: A Mini Review of the Clinical Manifestations, Investigation, and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

3. Genetic Pathogenesis and Molecular Basis of Disease

4. Clinical Features

4.1. Pulmonary Manifestations

4.2. Renal Manifestations

4.3. Cutaneous Manifestations

5. Clinical Investigation

5.1. Diagnostic Criteria (European BHD Consortium)

- Major Criterion: >5 fibrofolliculomas/trichodiscomas with at least one confirmed histologically.

- Minor Criteria:

- Basally located bilateral pulmonary cysts with no other known cause.

- Early-onset (<50 years), multifocal, or bilateral renal cancer.

- First-degree relative with confirmed BHD syndrome.

5.2. Differential Diagnosis

- Emphysema: apical pulmonary cysts in tobacco smokers.

- Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC): facial angiofibromas, renal angiomyolipomas, and cortical tubers.

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): diffuse pulmonary cysts in females, associated with TSC or sporadic.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): nodulocystic pulmonary disease in young adult smokers.

5.3. Genetic Testing

- Recurrent primary spontaneous pneumothorax and/or familial cases.

- Multiple bilateral pulmonary cysts, particularly in the lower lung zones.

- Bilateral or multifocal renal neoplasia.

- Familial or early onset (less than 45 years of age) RCC.

- Multiple cutaneous papules clinically consistent with fibrofolliculoma/trichodiscoma with at least one histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma.

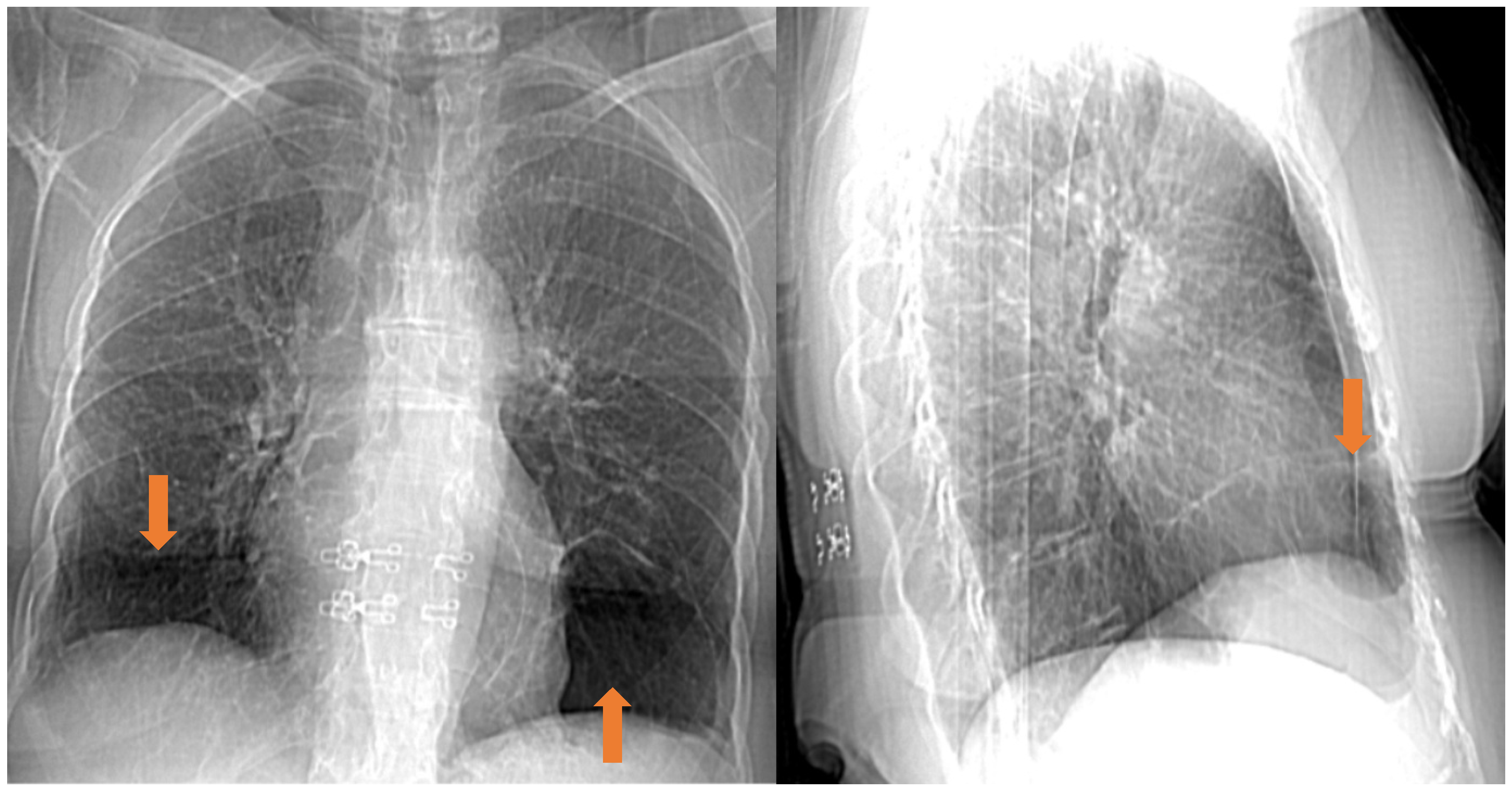

5.4. Radiological Features

5.5. Histopathological Features

6. Clinical Management

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nickerson, M.L.; Warren, M.B.; Toro, J.R.; Matrosova, V.; Glenn, G.; Turner, M.L.; Duray, P.; Merino, M.; Choyke, P.; Pavlovich, C.P.; et al. Mutations in a Novel Gene Lead to Kidney Tumors, Lung Wall Defects, and Benign Tumors of the Hair Follicle in Patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, A.R.; Hogg, G.R.; Dubé, W.J. Hereditary Multiple Fibrofolliculomas with Trichodiscomas and Acrochordons. Arch. Dermatol. 1977, 113, 1674–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Hong, S.B.; Sharma, N.; Warren, M.B.; Nickerson, M.L.; Iwamatsu, A.; Esposito, D.; Gillette, W.K.; Hopkins, R.F., 3rd; Hartley, J.L.; et al. Folliculin Encoded by the Bhd Gene Interacts with a Binding Protein, FNIP1, and AMPK, and is Involved in AMPK and mTOR Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15552–15557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kang, H.C.; Ganeshan, D.; Morani, A.; Gautam, R.; Choyke, P.L.; Kundra, V. The Abcs of Bhd: An In-Depth Review of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 209, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, J.S.; Rutt, V.; Oakley, A.M. Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, S.K.; Giraud, S.; Kahnoski, K.; Chen, J.; Motorna, O.; Nickolov, R.; Binet, O.; Lambert, D.; Friedel, J.; Lévy, R.; et al. Clinical and Genetic Studies of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 39, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantoan Ritter, L.; Annear, N.M.P.; Baple, E.L.; Ben-Chaabane, L.Y.; Bodi, I.; Brosson, L.; Cadwgan, J.E.; Coslett, B.; Crosby, A.H.; Davies, D.M.; et al. mTOR Pathway Diseases: Challenges and Opportunities from Bench to Bedside and the mTOR Node. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinlein, O.K.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Ruzicka, T.; Sattler, E.C. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: An Underdiagnosed Genetic Tumor Syndrome. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2018, 16, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orphanet. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Yngvadottir, B.; Richman, L.; Andreou, A.; Woodley, J.; Luharia, A.; Lim, D.; Maher, E.R.; Marciniak, S.J. Inherited Predisposition to Pneumothorax: Estimating the Frequency of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome from Genomics and Population Cohorts. Thorax 2025, 80, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, E.C.; Steinlein, O.K. Delayed Diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Due to Marked Intrafamilial Clinical Variability: A Case Report. BMC Med. Genet. 2018, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Mu, J.; Jiang, R.; Sharma, L.; Jie, Z. A Familial Case of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Complicated with Lung Cancer: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1581786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, J.; Pan, Z. Differential Diagnosis and a Novel Mutation in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Insights from 2 Cases. Am. J. Case Rep. 2025, 26, e947530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercent, A.; Ba, I.; Tchernitchko, D. Limited Diagnostic Utility of Prdm10 Analysis in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Experience in 313 Consecutive Patients. Clin. Genet. 2025, 108, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, K.; Corradetti, M.N.; Guan, K.L. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR Pathway in Human Disease. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daccord, C.; Good, J.M.; Morren, M.A.; Bonny, O.; Hohl, D.; Lazor, R. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 200042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakur, A.; Stewart, G.D.; Sadler, T.J.; Babar, J.L.; Warren, A.Y.; Scullion, S.; Ashok, A.H.; Karia, S.; Chipurovski, I.; Whitworth, J.; et al. Pulmonary Cysts as a Diagnostic Indicator of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome in Patients with Renal Neoplasm. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, J.D.; van de Beek, I.; Johannesma, P.C.; van Werkum, M.H.; van der Wel, T.; Wessels, E.M.; Gille, H.; Houweling, A.C.; Postmus, P.E.; Smit, H.J.M. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome in Apparent Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax Patients; Results and Recommendations for Clinical Practice. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, T.K.; Burns, M.; Scott, B.L.; Kucera, J.A.; Mullenix, P.S. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome—A Rare Cause of Recurrent Pneumothoraces in a Midshipman. Mil. Med. 2025, usaf318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatah, F.H.; Watson, J.T. Recurrent Spontaneous Pneumothorax as a Manifestation of the Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus 2025, 17, e84890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbar, B.; Alvord, W.G.; Glenn, G.; Turner, M.; Pavlovich, C.P.; Schmidt, L.; Walther, M.; Choyke, P.; Weirich, G.; Hewitt, S.M.; et al. Risk of Renal and Colonic Neoplasms and Spontaneous Pneumothorax in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2002, 11, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Van Denhove, A.; Guillot-Pouget, I.; Giraud, S.; Isaac, S.; Freymond, N.; Calender, A.; Pacheco, Y.; Devouassoux, G. Multiple Spontaneous Pneumothoraces Revealing Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2011, 28, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasumi, H.; Baba, M.; Hasumi, Y.; Furuya, M.; Yao, M. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Clinical and Molecular Aspects of Recently Identified Kidney Cancer Syndrome. Int. J. Urol. 2016, 23, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.Y.; Wang, X.T.; Zhang, H.Z.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ye, S.B.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.S.; Fang, R.; et al. GPNMB Expression Identifies FLCN-Associated Eosinophilic Renal Tumors with Heterogeneous Clinicopathologic Spectrum and Gene Expression Profiles. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2025, 49, 1158–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.A.; Dunlop, E.A.; Champion, J.D.; Doubleday, P.F.; Claessens, T.; Jalali, Z.; Seifan, S.; Perry, I.A.; Giles, P.; Harrison, O.; et al. Characterizing the Tumor Suppressor Activity of FLCN in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Cell Models through Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis. Oncogene 2025, 44, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Dasari, S.; Warren, R.R.; Shen, W.; Urban, R.M.; Stanton, M.L.; Lohse, C.M.; Holdren, M.A.; Hoenig, M.F.; Pitel, B.A.; et al. Renal Neoplasia in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Integrated Histopathologic, Bulk, and Single-cell Transcriptomic Analysis. Eur. Urol. 2025, 88, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, O.; Ohmori, T.; Miike, K.; Tanigawa, S.; Wilan Krisna, L.A.; Calcagnì, A.; Ballabio, A.; Kubota, Y.; Schmidt, L.S.; Linehan, W.M.; et al. Folliculin Deletion in the Mouse Kidney Results in Cystogenesis of the Loops of Henle Via Aberrant TFEB Activation. Am. J. Pathol. 2025, 195, 1643–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.R.; Glenn, G.; Duray, P.; Darling, T.; Weirich, G.; Zbar, B.; Linehan, M.; Turner, M.L. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: A Novel Marker of Kidney Neoplasia. Arch. Dermatol. 1999, 135, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirwani, S.; Ghattas, S.; Wilson, N.; Hunt, S.; Callaway, A.; Side, L.; Bate, J. Multiple Early Onset Atypical Cutaneous Fibrous Histiocytomas in Multilocus Inherited Neoplasia Allele Syndrome Involving TP53 and FLCN Genes. J. Med. Genet. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, S.; Chuki, E.; Veeraraghavan, P.; Jedlinski-Obrzut, M.; Bukhari, K.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J.; Gubbi, S. Thyroid Carcinoma in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Case Series and Review of Literature. Thyroid 2025, 35, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, A.M.; Hassan, F.; Dawkins, A.A.; Dueber, J.C.; Allison, D.B.; Bocklage, T.J. Oncocytic Thyroid Tumours with Pathogenic FLCN Mutations Mimic Oncocytic Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma on Fine-Needle Aspiration. Cytopathology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custode, B.M.; Annunziata, F.; Dos Santos Matos, F.; Schiano, V.; Maffia, V.; Lillo, M.; Colonna, R.; De Cegli, R.; Ballabio, A.; Pastore, N. Folliculin Depletion Results in Liver Cell Damage and Cholangiocarcinoma through MiT/TFE Activation. Cell Death Differ. 2025, 32, 1460–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercent, A.; Tchernitchko, D. Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome and Multiple Myeloma? Intern. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, F.; Sakamoto, T.; Kai, H.; Usui, T.; Kawanishi, K.; Matsuoka, R.; Ishitsuka, K.; Makishima, K.; Suma, S.; Maruyama, Y.; et al. Multiple Myeloma in a Patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Intern. Med. 2025, 64, 2764–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menko, F.H.; van Steensel, M.A.; Giraud, S.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Richard, S.; Ungari, S.; Nordenskjöld, M.; Hansen, T.V.; Solly, J.; Maher, E.R. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, D.; Zou, W.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, C.; Min, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, B.; Ye, M.; et al. A Rapid NGS Strategy for Comprehensive Molecular Diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome in Patients with Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.; Guo, T.; Basit, A.; Liu, L.; Luo, H. Clinical and Genetic Investigations of Five Chinese Families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1613154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geilswijk, M.; Genuardi, M.; Woodward, E.R.; Nightingale, K.; Huber, J.; Madsen, M.G.; Liekelema-van der Heij, D.; Lisseman, I.; Marlé-Ballangé, J.; McCarthy, C.; et al. ERN GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Surveillance and Management of People with Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.P.; Gross, B.H.; Holloway, B.J.; Seely, J.; Stark, P.; Kazerooni, E.A. Thoracic CT Findings in Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 196, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Cha, Y.K.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.H. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Characteristic CT Findings Differentiating It from Other Diffuse Cystic Lung Diseases. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 23, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterclova, M.; Doubkova, M.; Doubek, M.; Macek, M. The Necessity of Geneticist and Pulmonologist Collaboration in the Treatment of Monogenic Interstitial Lung Diseases in Adults. Breathe 2025, 21, 240255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Kobayashi, E.; Hayashi, T.; Iwabuchi, C.; Ishiko, A.; Kishikawa, S.; Tsuboshima, K.; Kurihara, M.; Takahashi, K.; et al. A Collaborative Study to Disseminate the Clinical Practice of Diagnosing and Managing Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome in Japan. Respir. Investig. 2025, 63, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel, L.; van Hulst, R.A.; van Hest, L.; van Moorselaar, R.; Boerrigter, B.G.; Franken, S.M.; Wolthuis, R.; Dubbink, H.J.; Marciniak, S.J.; Gupta, N.; et al. Recommendations on Scuba Diving in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2023, 17, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulle, M.; Puri, H.; Asaf, B.; Bishnoi, S.; Bhardwaj, D.; Kumar, A. Re-do VATS for Recurrent Pneumothorax in a Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Patient. Multimed. Man. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangeria, S.; Asaf, B.B.; Bishnoi, S.; Pulle, M.V.; Puri, H.V.; Kumar, A. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Presenting as Recurrent Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax: VATS. Indian J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2025, 41, 1092–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, B.G.; das Posses Bridi, G.; Heiden, G.I.; Salge, J.M.; Queiroz, D.S.; Ribeiro Carvalho, C.R.; de Carvalho, C.R.F. Mechanisms of Exercise Limitation and Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Patients with Cystic Lung Diseases. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2025, 19, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, L.; Metwalli, A.R.; Middelton, L.A.; Marston Linehan, W. Diagnosis and Management of BHD-Associated Kidney Cancer. Fam. Cancer 2013, 12, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Li, C.; Xu, D.; Xu, L. Successful Treatment of Advanced Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome-Associated Renal Cell Carcinoma with Sarcomatoid Dedifferentiation Using Anlotinib Combined with PD-1 Inhibitor after First-Line Therapy Failure: A Case Report. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 23, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.S.M.; Medina, A.; Esmail, R.; Trestrail, T.; Rivera, F.C. Long-Term Outcomes After Kidney Transplantation in a Recipient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome. Case Rep. Transplant. 2025, 2025, 5889953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R. Anesthetic Management for Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Case. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2025, 19, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatashima, N.; Takahashi, K.; Dozono, J.; Kida, H.; Matsuba, S. Tailored Anesthetic Management in a Patient with Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome: Navigating the Risk of Pneumothorax and Renal Dysfunction in a Case Report. Cureus 2025, 17, e85115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Burgos, A.; Acosta, E.H.; Márquez, F.V.; Mendiola, M.; Herrera-Ceballos, E. Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome in a Patient with Melanoma and a Novel Mutation in the FCLN gene. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013, 52, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, G.; Cannarozzo, G.; Sannino, M.; Pieri, L.; Fusco, I.; Negosanti, F. Fibrofolliculomas in Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome Treated with a CO2 and Dye Laser Combination: A Case Report and Literature Review. Dermatol. Rep. 2025, 17, 10066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ntinidi, C.; Tomos, I.; Matthaiou, A.M.; Bizymi, N.; Liapikou, A. Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome: A Mini Review of the Clinical Manifestations, Investigation, and Management. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120583

Ntinidi C, Tomos I, Matthaiou AM, Bizymi N, Liapikou A. Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome: A Mini Review of the Clinical Manifestations, Investigation, and Management. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120583

Chicago/Turabian StyleNtinidi, Christina, Ioannis Tomos, Andreas M. Matthaiou, Nikoleta Bizymi, and Adamantia Liapikou. 2025. "Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome: A Mini Review of the Clinical Manifestations, Investigation, and Management" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120583

APA StyleNtinidi, C., Tomos, I., Matthaiou, A. M., Bizymi, N., & Liapikou, A. (2025). Birt–Hogg–Dubé Syndrome: A Mini Review of the Clinical Manifestations, Investigation, and Management. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120583