Sonographic and Clinical Progression of Adenomyosis and Coexisting Endometriosis: Long-Term Insights and Management Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

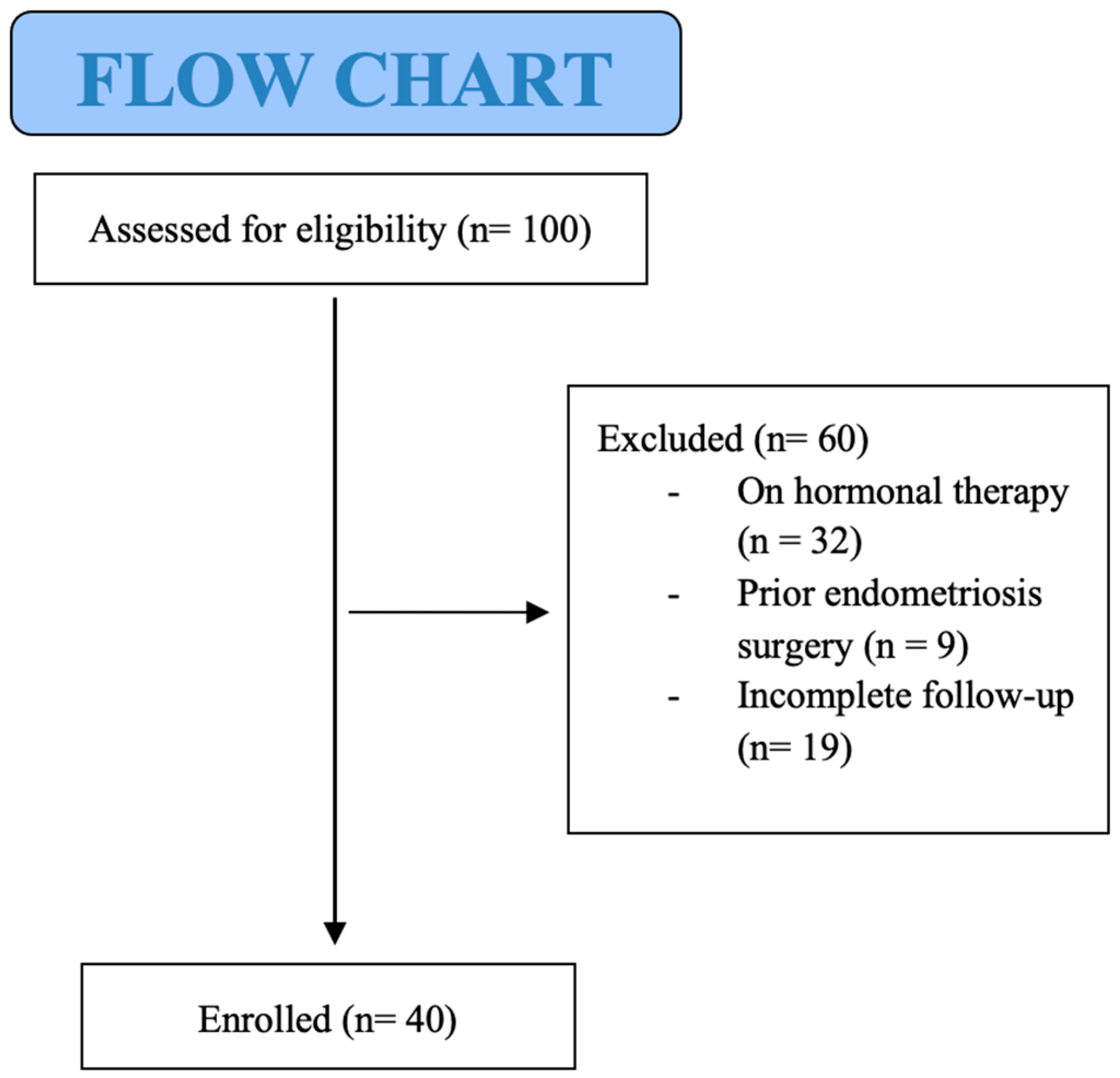

2. Materials and Methods

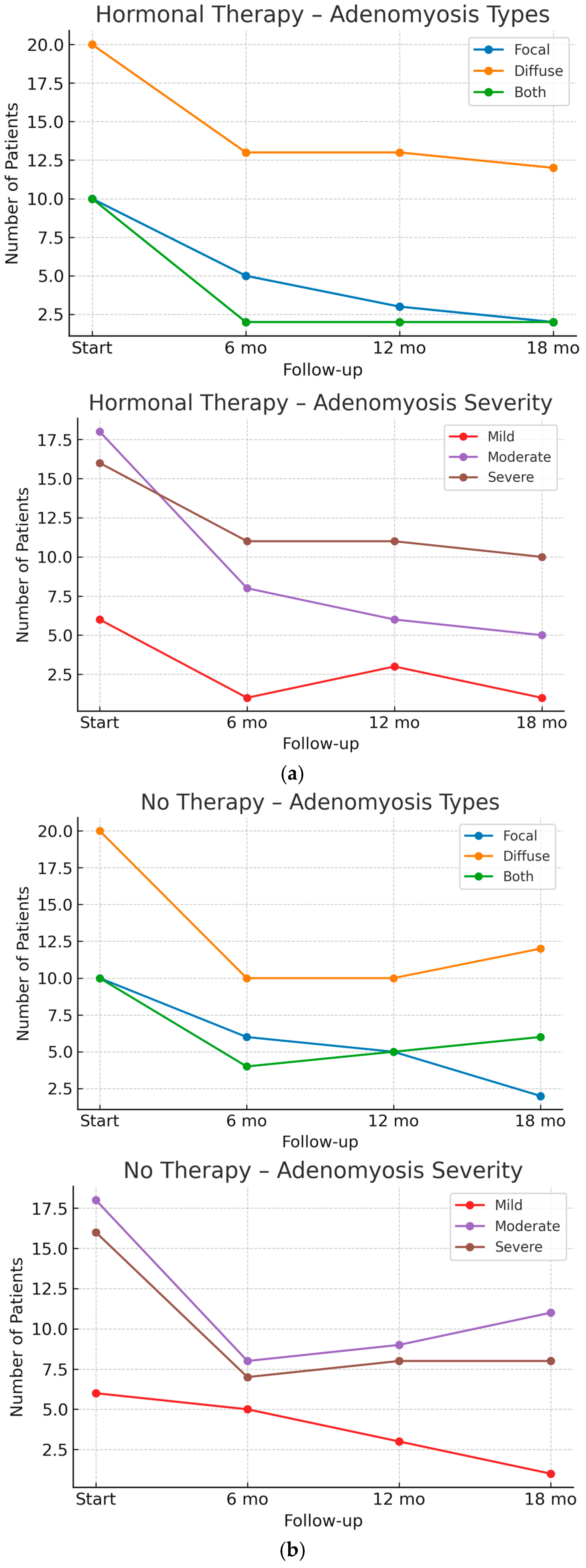

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| 1 | Chronic Pelvic Pain |

| DE | Deep Endometriosis |

| FUP | Follow Up |

| HMB | Heavy Menstrual Bleeding |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NA | Not Applicable |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| PBAC | Pictorial Blood loss Analysis Chart |

| RVS | rectovaginal septum |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TVS | Transvaginal Sonography |

| US | Ultrasound |

| USL | Uterosacral ligament |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Hudelist, G.; Keckstein, J.; Wright, J.T. The migrating adenomyoma: Past views on the etiology of adenomyosis and endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exacoustos, C.; Morosetti, G.; Conway, F.; Camilli, S.; Martire, F.G.; Lazzeri, L.; Piccione, E.; Zupi, E. New sonographic classification of adenomyosis: Do type and degree of adenomyosis correlate to severity of symptoms? J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, T.; Dueholm, M.; Leone, F.P.; Valentin, L.; Rasmussen, C.K.; Votino, A.; Van Schoubroeck, D.; Landolfo, C.; Installé, A.J.; Guerriero, S.; et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: A consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol 2015, 46, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, M.J.; Van den Bosch, T.; de Leeuw, R.A.; Dueholm, M.; Exacoustos, C.; Valentin, L.; Hehenkamp, W.J.K.; Groenman, F.; De Bruyn, C.; Rasmussen, C.; et al. Consensus on revised definitions of Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) features of adenomyosis: Results of modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parazzini, F.; Bertulessi, C.; Pasini, A.; Rosati, M.; Di Stefano, F.; Shonauer, S.; Vicino, M.; Aguzzoli, L.; Trossarelli, G.F.; Massobrio, M.; et al. Determinants of short-term recurrence rate of endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 121, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Parazzini, F.; Oldani, S.; Panazza, S.; Bramante, T.; Crosignani, P.G. Adenomyosis at hysterectomy: A study on frequency distribution and patient characteristics. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; d’Abate, C.; Schettini, G.; Cimino, G.; Ginetti, A.; Colombi, I.; Cannoni, A.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Adenomyosis and Adolescence: A Challenging Diagnosis and Complex Management. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazot, M.; Daraï, E. Role of transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyendecker, G.; Bilgicyildirim, A.; Inacker, M.; Stalf, T.; Huppert, P.; Mall, G.; Böttcher, B.; Wildt, L. Adenomyosis and endometriosis: Revisiting their association and further insights into the mechanisms of auto-traumatisation. An MRI study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 291, 917–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, L.; Andersson, K.L.; Angioni, S.; Arena, A.; Arena, S.; Bartiromo, L.; Berlanda, N.; Bonin, C.; Candiani, M.; Centini, G.; et al. How to Manage Endometriosis in Adolescence: The Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club Approach. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Buffo, C.; Bandini, V.; Cipriani, S.; Chiaffarino, F.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, M.D.E. Prevalence of adenomyosis in symptomatic adolescents and young women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. FS Rev. 2025, 6, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, P.E.; Critchley, H.O.D.; Lumsden, M.A.; Campbell-Brown, M.; Douglas, A.; Murray, G.D. Menorrhagia I: Measured blood loss, clinical features, and outcome in women with heavy periods: A survey with follow-up data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Palumbo, M.; Reppuccia, S.; Iorio, G.G.; Nocita, E.; Monaco, G.; Iacobini, F.; Soreca, G.; Exacoustos, C. Evaluation of menstrual blood loss (MBL) by self-perception and pictorial methods and correlation to uterine myometrial pathology. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, G.; Fruscalzo, A.; Youssef, Y.; Kheil, M.; Tawil, T.; Nehme, J.; Pirtea, P.; Guani, B.; Afaneh, H.; Ayoubi, J.M.; et al. Adenomiosi: An Updated Review on Diagnosis and Classification. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exacoustos, C.; Lazzeri, L.; Martire, F.G.; Russo, C.; Martone, S.; Centini, G.; Piccione, E.; Zupi, E. Ultrasound findings of adenomyosis in adolescents: Type and grade of the disease. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, S.; Condous, G.; van den Bosch, T.; Valentin, L.; Leone, F.P.; Van Schoubroeck, D.; Exacoustos, C.; Installé, A.J.; Martins, W.P.; Abrao, M.S.; et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: A consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Holsbeke, C.; Van Calster, B.; Guerriero, S.; Savelli, L.; Paladini, D.; Lissoni, A.A.; Czekierdowski, A.; Fischerova, D.; Zhang, J.; Mestdagh, G.; et al. Endometriomas: Their ultrasound characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 35, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosens, I.; Gordts, S.; Habiba, M.; Benagiano, G. Uterine Cystic Adenomyosis: A Disease of Younger Women. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015, 28, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapron, C.; Vannuccini, S.; Santulli, P.; Abrão, M.S.; Carmona, F.; Fraser, I.S.; Gordts, S.; Guo, S.-W.; Just, P.-A.; Noel, J.-C.; et al. Diagnosing adenomyosis: An integrated clinical and imaging. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannuccini, S.; Meleca, C.; Toscano, F.; Mertino, P.; Pampaloni, F.; Fambrini, M.; Bruni, V.; Petraglia, F. Adenomyosis diagnosis among adolescents and young women with dysmenorrhoea and heavy menstrual bleeding. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2024, 48, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar, J.L.; Vara, J.; Usandizaga, C.; Ajossa, S.; Pascual, M.A.; Guerriero, S. Transvaginal ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing adenomyosis: A systematic review and head-to-head meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 16, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, M.; Guo, S.W.; Benagiano, G. Adenomyosis and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: Review of the Evidence. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- d’Otreppe, J.; Patino-García, D.; Piekos, P.; de Codt, M.; Manavella, D.D.; Courtoy, G.E.; Orellana, R. Exploring the Endocrine Mechanisms in Adenomyosis: From Pathogenesis to Therapies. Endocrines 2024, 5, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetera, G.E.; Merli, C.E.M.; Facchin, F.; Viganò, P.; Pesce, E.; Caprara, F.; Vercellini, P. Non-response to first-line hormonal treatment for symptomatic endometriosis: Overcoming tunnel vision. A narrative review. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Frisch, E.H.; Falcone, T. From Diagnosis to Fertility: Optimizing Treatment of Adenomyosis for Reproductive Health. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gruber, T.M.; Mechsner, S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: The Origin of Pain and Subfertility. Cells 2021, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- As-Sanie, S.; Till, S.R.; Schrepf, A.D.; Griffith, K.C.; Tsodikov, A.; Missmer, S.A.; Clauw, D.J.; Brummett, C.M. Incidence and predictors of persistent pelvic pain following hysterectomy in women with chronic pelvic pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 568.e1–568.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, D.; Raffone, A.; Renzulli, F.; Sanna, G.; Raspollini, A.; Bertoldo, L.; Maletta, M.; Lenzi, J.; Rovero, G.; Travaglino, A.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Central Sensitization in Women with Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 73–80.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentles, A.; Goodwin, E.; Bedaiwy, Y.; Marshall, N.; Yong, P.J. Nociplastic Pain in Endometriosis: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dedes, I.; Kolovos, G.N.; Mueller, M.D. Non surgical Treatment of Adenomyosis. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2024, 13, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Endo-metriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.M.; Samy, A.; Atwa, K.; Ghoneim, H.M.; Lotfy, M.; Saber Mohammed, H.; Abdellah, A.M.; El Bahie, A.M.; Aboelroose, A.A.; El Gedawy, A.M.; et al. The role of levonorgestrel intra-uterine system in the management of adenomyosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 99, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercorio, A.; Della Corte, L.; Dell’Aquila, M.; Pacella, D.; Bifulco, G.; Giampaolino, P. Adenomyosis: A potential cause of surgical failure in treating dyspareunia in rectovaginal septum endometriosis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 168, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignali, M.; Belloni, G.M.; Pietropaolo, G.; Barbasetti Di Prun, A.; Barbera, V.; Angioni, S.; Pino, I. Effect of Dienogest therapy on the size of the endometrioma. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, A.; Nguyen, D.B.; Smith, J.P.; Mansour, F.W.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Zakhari, A. Medical Management of Ovarian Endometriomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 143, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martire, F.G.; Costantini, E.; D’Abate, C.; Schettini, G.; Sorrenti, G.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Endometriosis and Ade-nomyosis: From Pathogenesis to Follow-Up. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Epis, M.; Casarin, J.; Bordi, G.; Gisone, E.B.; Cattelan, C.; Rossetti, D.O.; Ciravolo, G.; Gozzini, E.; Conforti, J.; et al. Long-term therapy with dienogest or other oral cyclic estrogen-progestogen can reduce the need for ovari. Women’s Health 2024, 20, 17455057241252573. [Google Scholar]

- Etrusco, A.; Barra, F.; Chiantera, V.; Ferrero, S.; Bogliolo, S.; Evangelisti, G.; Oral, E.; Pastore, M.; Izzotti, A.; Venezia, R.; et al. Current Medical Therapy for Adenomyosis: From Bench to Bedside. Drugs 2023, 83, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercan, R.; Benlioglu, C.; Aksakal, G.E. Critical appraisal and narrative review of the literature in IVF/ICSI patients with adenomyosis and endometriosis. Front. Reprod. Health 2024, 6, 1525705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borghese, G.; Doglioli, M.; Orsini, B.; Raffone, A.; Neola, D.; Travaglino, A.; Rovero, G.; Del Forno, S.; de Meis, L.; Locci, M.; et al. Progression of adenomyosis: Rate and associated factors. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2024, 167, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlov, S.; Sladkevicius, P.; Jokubkiene, L. Evaluating the development of endometriosis and adenomyosis lesions over time: An ultrasound study of symptomatic women. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2024, 103, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnez, J.; Stratopoulou, C.A.; Dolmans, M.M. Endometriosis and adenomyosis: Similarities and differences. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 92, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Waseem, S.; Luo, L. Advances in the diagnosis and management of endometriosis: A comprehensive review. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 266, 155813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottolina, J.; Villanacci, R.; D’Alessandro, S.; He, X.; Grisafi, G.; Ferrari, S.M.; Candiani, M. Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Modern Concepts of Their Clinical Outcomes, Treatment, and Management. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Jia, S.; Leng, J. Pregnancy outcomes in women with infertility and coexisting endometriosis and adenomyosis after laparoscopic surgery: A long-term retrospective follow-up study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulisano, M.; Gulino, F.A.; Incognito, G.; Cimino, M.; Dilisi, M.; Di Stefano, A.; D’urso, V.; Cannone, F.; Martire, F.G.; Palumbo, M. Role of hysteroscopy on infertility: The eternal dilemma. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 50, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Ou, H.T.; Wu, M.H.; Yen, C.F.; Taiwan Endometriosis Society Adenomyosis Consensus Group. Expert Consensus on the Management of Adenomyosis: A Modified Delphi Method Approach by the Taiwan Endometriosis Society. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2025, 14, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; AlAshqar, A.; El Sabeh, M.; Miyashita-Ishiwata, M.; Reschke, L.; Brennan, J.T.; Fader, A.; Borahay, M.A. Diet and Nutrition in Gynecological Disorders: A Focus on Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Patients Characteristics | Total Study Population (n = 40) ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 38.5 ± 4.2 SD |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 20.2 ± 2.1 SD |

| Age at Menarche | 12.6 ± 1.5 SD |

| Pregnancy History | 0.8 ± 0.3 SD |

| Parity | 17/40 (42.5%) |

| Nulliparity | 23/40 (57.5%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Dysmenorrhea | 32/40 (80%) |

| Dyspareunia | 18/40 (45%) |

| Dysuria | 7/40 (17.5%) |

| Dyschezia | 8/40 (20%) |

| HMB (PBAC > 100) | 30/40 (75%) |

| Chronic Pelvic Pain | 16/40 (40%) |

| Other Symptoms (headaches, bowel irregularities, leukorrhea, mood changes, urinary tract infections) | 9/40 (22.5%) |

| Types Of Adenomyosis | |

| Focal Adenomyosis | 10/40 (25%) |

| Diffuse Adenomyosis | 20/40 (50%) |

| Both (Focal + Diffuse Adenomyosis) | 10/40 (25%) |

| Internal Myometrium | 13/40 (32.5%) |

| External Myometrium | 20/40 (50%) |

| Both (Internal + External Myometrium) | 7/40 (17.5%) |

| Mild Degree | 6/40 (15%) |

| Moderate Degree | 18/40 (45%) |

| Severe Degree | 16/40 (40%) |

| Us Findigns Of Endometriosis | |

| Endometrioma | 5/40 (12.5%) |

| Bowel Endometriosis | 4/40 (10%) |

| Bladder Endometriosis | 2/40 (5%) |

| Deep Endometriosis USL | 16/40 (40%) 13/40 (32.5%) |

| RVS | 3/40 (7.5%) |

| Symptoms | n | Focal Type | Diffuse Type | Both (Focal + Diffuse Type) | Internal Myometrium | External Myometrium | Both (Internal + External Myometrium | Mild Degree | Moderate Degree | Severe Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysmenorrhea | 32 | 9 (28.1%) | 20 (62.5%) | 3 (9.4%) | 12 (37.5%) | 18 (56.3%) | 2 (6.3%) | 5 (15.6%) | 15 (46.9%) | 12 (37.5%) |

| HMB (PBAC > 100) | 30 | 10 (33.3%) | 16 (53.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 13 (43.3%) | 10 (33.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | 6 (20%) | 15 (50%) | 9 (30%) |

| Dyspareunia | 18 | 7 (38.9%) | 9 (50%) | 2 (11.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | 10 (55.6%) | 1 (5.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | 11 (61.1%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Chronic Pelvic Pain | 16 | 4 (25%) | 9 (56.3%) | 3 (18.7%) | 6 (37.5%) | 8 (50%) | 2 (12.5%) | 4 (25%) | 6 (37.5%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| a | ||||||||

| Ultrasound Endometriosis Findings | at Starting FUP (n = 18) | 6 Months FUP (n = 9) | 12 Months FUP (n = 9) | 18 Months FUP (n = 9) | ||||

| Not on Therapy | On Hormonal Therapy | |||||||

| n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | |

| DEEP ENDOMETRIOSIS | ||||||||

| RVS | 3 | 12.3 ± 3.2 | 2 | 12.1 ± 4.1 | 2 | 12.9 ± 2.6 | 2 | 12.2 ± 3.5 |

| USL bilateral | 13 | 7.1 ± 3.5 | 8 | 7.9 ± 2.4 | 8 | 8.1 ± 4.1 | 8 | 7.4 ± 3.2 |

| ENDOMETRIOMA | 5 | 38.4 ± 11.1 | 3 | 31.9 ± 10.6 * | 3 | 20.7 ± 7.9 ** | 3 | 18.5 ± 8.1 *** |

| BOWEL ENDOMETRIOSIS | 4 | 15.2 ± 3.3 | 1 | 16.1 ± NA | 1 | 15.3 ± NA | 1 | 15.8 ± NA |

| BLADDER ENDOMETRIOSIS | 2 | 10.4 ± 2.8 | 1 | 11.2 ± NA | 1 | 10.6 ± NA | 1 | 10.4 ± NA |

| b | ||||||||

| Ultrasound Endometriosis Findings | At Starting FUP (n = 18) | 6 Months FUP (n = 9) | 12 Months FUP (n = 9) | 18 Months FUP (n = 9) | ||||

| Not on Therapy | Not on Therapy | |||||||

| n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | n | Max Diameter (mm) Mean ± SD | |

| DEEP ENDOMETRIOSIS | ||||||||

| RVS | 3 | 12.3 ± 3.2 | 1 | 12.5 ± NA | 1 | 12.8 ± NA | 1 | 12.5 ± NA |

| USL bilateral | 13 | 7.1 ± 3.5 | 5 | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 5 | 7.6 ± 2.8 | 5 | 7.5 ± 3.7 |

| ENDOMETRIOMA | 5 | 38.4 ± 11.1 | 2 | 38.9 ± 10.4 | 2 | 39.1 ± 7.6 | 2 | 40.2 ± 9.1 |

| BOWEL ENDOMETRIOSIS | 4 | 15.2 ± 3.3 | 3 | 15.7 ± 1.2 | 3 | 15.5 ± 2.9 | 3 | 15.4 ± 3.7 |

| BLADDER ENDOMETRIOSIS | 2 | 10.4 ± 2.8 | 1 | 10.8 ± NA | 1 | 10.7 ± NA | 1 | 10.2 ± NA |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | At Starting (n = 40) | 6 Months FUP (n = 40) | 12 Months FUP (n = 40) | 18 Months FUP (n = 40) | ||||

| n | VAS Mean ± SD Presence n (%) | n | VAS Mean ± SD Presence n (%) | n | VAS Mean ± SD Presence n (%) | n | VAS Mean ± SD Presence n (%) | |

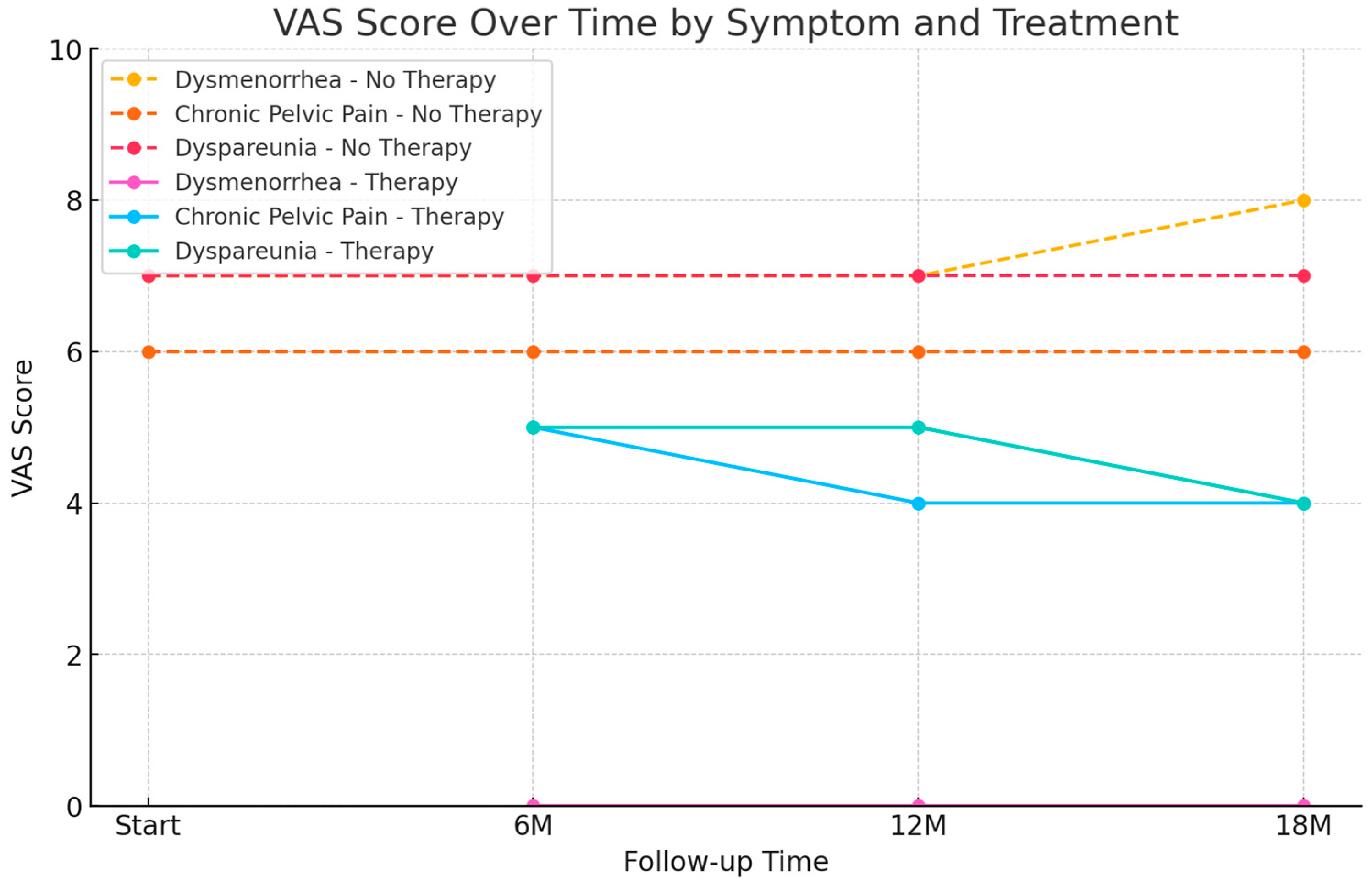

| DYSMENORRHEA | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 32 | VAS 7 ± 1.8 SD | 12 | VAS 7 ± 1.8 SD | 12 | VAS 7 ± 1.8 SD | 12 | VAS 8 ± 0.7 SD |

| Therapy | 0 | 20 | VAS 0 * | 20 | VAS 0 | 20 | VAS 0 | |

| CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 16 | VAS 6 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 6 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 6 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 6 ± 1.2 SD |

| Therapy | 0 | 10 | VAS 5 ± 1.5 SD | 10 | VAS 4 ± 1.5 SD | 10 | VAS 4 ± 1.5 SD | |

| HMB | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 30 | 75% | 10 | 100% | 10 | 100% | 10 | 100% |

| Therapy | 0 | 20 | 0% * | 20 | 0% | 20 | 0% | |

| DYSPAREUNIA | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 18 | VAS 7 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 7 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 7 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 7 ± 1.2 SD |

| Therapy | 0 | 12 | VAS 5 ± 0.6 SD | 12 | VAS 5 ± 0.6 SD | 12 | VAS 4 ± 0.6 SD | |

| DYSCHEZIA | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 8 | VAS 6 ± 1.3 SD | 2 | VAS 6 ± 1.3 SD | 2 | VAS 6 ± 1.3 SD | 2 | VAS 6 ± 1.3 SD |

| Therapy | 0 | 6 | VAS 5 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 5 ± 1.2 SD | 6 | VAS 5 ± 1.2 SD | |

| DYSURIA | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 7 | VAS 6 ± 1.1 SD | 3 | VAS 6 ± 1.1 SD | 3 | VAS 6 ± 1.1 SD | 3 | VAS 6 ± 1.1 SD |

| Therapy | 0 | 4 | VAS 4 ± 0.7 SD | 4 | VAS 4 ± 0.7 SD | 4 | VAS 4 ± 0.7 SD | |

| OTHER SYMPTOMS | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 9 | VAS 6 ± 1.0 SD | 3 | VAS 6 ± 1.0 SD | 3 | VAS 6 ± 1.0 SD | 3 | VAS 6 ± 1.0 SD |

| Therapy | 0 | 6 | VAS 4 ± 0.8 SD | 6 | VAS 4 ± 0.8 SD | 6 | VAS 4 ± 0.8 SD | |

| SIDE EFFECTS | ||||||||

| No Therapy | 0 | / | 0 | / | 0 | / | 0 | / |

| Therapy | 0 | / | 3 | / | 7 | / | 9 | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martire, F.G.; d’Abate, C.; Costantini, E.; De Bonis, M.; Sorrenti, G.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Lazzeri, L. Sonographic and Clinical Progression of Adenomyosis and Coexisting Endometriosis: Long-Term Insights and Management Perspectives. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110538

Martire FG, d’Abate C, Costantini E, De Bonis M, Sorrenti G, Centini G, Zupi E, Lazzeri L. Sonographic and Clinical Progression of Adenomyosis and Coexisting Endometriosis: Long-Term Insights and Management Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(11):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110538

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartire, Francesco Giuseppe, Claudia d’Abate, Eugenia Costantini, Maria De Bonis, Giuseppe Sorrenti, Gabriele Centini, Errico Zupi, and Lucia Lazzeri. 2025. "Sonographic and Clinical Progression of Adenomyosis and Coexisting Endometriosis: Long-Term Insights and Management Perspectives" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 11: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110538

APA StyleMartire, F. G., d’Abate, C., Costantini, E., De Bonis, M., Sorrenti, G., Centini, G., Zupi, E., & Lazzeri, L. (2025). Sonographic and Clinical Progression of Adenomyosis and Coexisting Endometriosis: Long-Term Insights and Management Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(11), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110538