Preoperative Breast MRI and Histopathology in Breast Cancer: Concordance, Challenges and Emerging Role of CEM and mpMRI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria (PICOS)

- Population (P): Adult women with biopsy-proven breast cancer (IDC, ILC, DCIS).

- Index test (I): Preoperative breast MRI (conventional DCE-MRI or mpMRI including DWI ± MRS); comparative analyses with CEM when available.

- Comparator (C): Histopathology (surgical specimen or core biopsy) as the reference standard.

- Outcomes (O): Diagnostic performance (sensitivity and specificity), size concordance, effect on surgical management, neoadjuvant response (pCR) prediction.

- Study design (S): Prospective and retrospective cohorts, diagnostic accuracy studies, randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Items Extracted

- Study characteristics (Author, year of publication, study design)

- Patient demographics (Sample size, age distribution)

- Tumor characteristics (Subtype, size, stage, grade, and multifocality)

- Imaging methods (Use of MRI, supplementary imaging techniques)

- Outcomes (MRI-histopathology concordance, sensitivity, specificity, correlation coefficients and impact on surgical management)

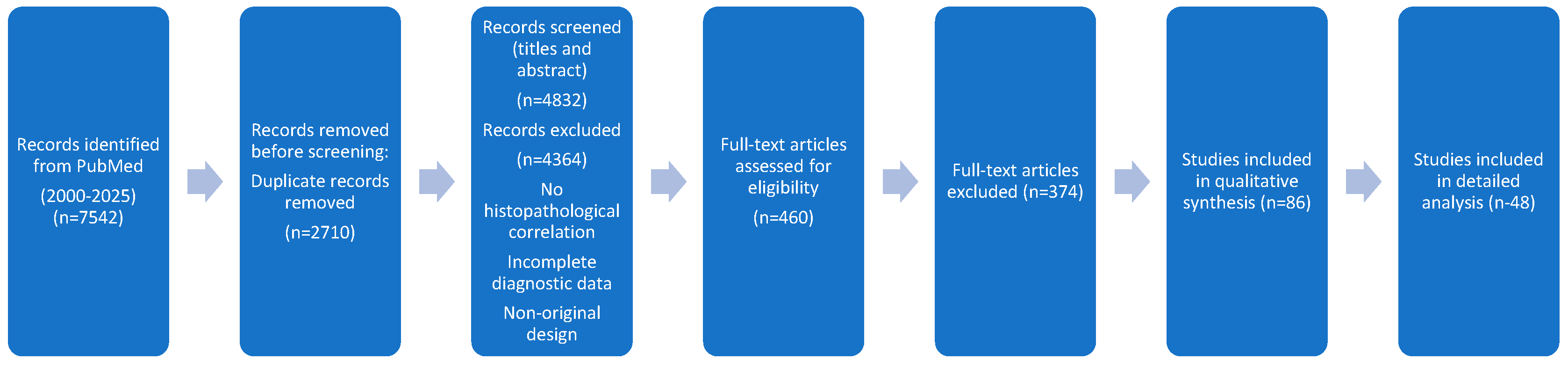

2.5. PRISMA Flow Diagram

2.6. Study Heterogeneity and Methodological Overview

3. Results

3.1. Factors Affecting Concordance Between Breast MRI and Histopathology

3.1.1. Breast Cancer Subtype

3.1.2. Tumor Size

3.1.3. Tumor Stage

3.1.4. Tumor Grade

3.1.5. Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy

3.2. MRI Diagnostic Performance: Sensitivity Considerations

3.3. Specificity Considerations

3.4. Statistical Measures of Concordance

3.5. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM)

3.6. Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI)

3.7. Light Quantitative Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Interpretation of MRI Performance

4.2. Knowledge Gaps and Controversies

4.3. Comparative Evidence with Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM)

4.4. Advances in Multiparametric MRI

4.5. Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Radiomics

4.6. Guidelines and Clinical Recommendations

4.7. Limitations of This Review

4.8. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CEM | Contrast-Enhanced Mammography |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DCE-MRI | Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| MRS | Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| IDC | Invasive Ductal Carcinoma |

| ILC | Invasive Lobular Carcinoma |

| DCIS | Ductal Carcinoma in Situ |

| pCR | Pathologic Complete Response |

| BPE | Background Parenchymal Enhancement |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| EUSOBI | European Society of Breast Imaging |

| ACR | American College of Radiology |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavaddat, N.; Antoniou, A.C.; Mooij, T.M.; Hooning, M.J.; Heemskerk-Gerritsen, B.A.; Noguès, C.; Gauthier-Villars, M.; Caron, O.; Gesta, P.; Pujol, P. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, natural menopause, and breast cancer risk: An international prospective cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 8, Erratum in Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 25. https://Doi.Org/10.1186/S13058-020-01259-W. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daly, M.B.; Pal, T.; Berry, M.P.; Buys, S.S.; Dickson, P.; Domchek, S.M.; Elkhanany, A.; Friedman, S.; Goggins, M.; Hutton, M.L.; et al. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, R.M.; Athanasiou, A.; Baltzer, P.A.T.; Camps-Herrero, J.; Clauser, P.; Fallenberg, E.M.; Forrai, G.; Fuchsjäger, M.H.; Helbich, T.H.; Killburn-Toppin, F.; et al. Breast cancer screening in women with extremely dense breasts recommendations of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI). Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 4036–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, Y.; Reig, B.; Heacock, L.; Bennett, D.L.; Heller, S.L.; Moy, L. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Screening of Breast Cancer. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 59, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peters, N.H.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.; Zuithoff, N.P.; Mali, W.P.; Moons, K.G.; Peeters, P.H. Meta-analysis of MR imaging in the diagnosis of breast lesions. Radiology 2008, 246, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardanelli, F.; Boetes, C.; Borisch, B.; Decker, T.; Federico, M.; Gilbert, F.J.; Helbich, T.; Heywang-Köbrunner, S.H.; Kaiser, W.A.; Kerin, M.J.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast: Recommendations from the EUSOMA working group. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1296–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Xu, Z.; Wei, D.; Xu, C. A meta-analysis of the association between preoperative magnetic resonance imaging and surgical outcomes in newly diagnosed breast cancer. Arch. Med. Sci. 2024, 20, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssami, N.; Ciatto, S.; Macaskill, P.; Lord, S.J.; Warren, R.M.; Dixon, J.M.; Irwig, L. Accuracy and surgical impact of magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer staging: Systematic review and meta-analysis in detection of multifocal and multicentric cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3248–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmon, E.; Alster, T.; Maly, B.; Kadouri, L.; Kleinman, T.A.; Sella, T. Preoperative MRI for Evaluation of Extent of Disease in IDC Compared to ILC. Clin. Breast Cancer 2022, 22, e745–e752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinovich, M.L.; Houssami, N.; Macaskill, P.; Sardanelli, F.; Irwig, L.; Mamounas, E.P.; von Minckwitz, G.; Brennan, M.E.; Ciatto, S. Meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting residual breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, L.M.; den Dekker, B.M.; Gilhuijs, K.G.A.; van Diest, P.J.; van der Wall, E.; Elias, S.G. MRI to assess response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer subtypes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.C.; McDonald, E.S. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the breast: Protocol optimization, interpretation, and clinical applications. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2013, 21, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhong, M.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Huang, R.; Wang, M.; Fan, W.; Dai, Z.; Chen, X. Readout-Segmented Echo-Planar Diffusion-Weighted MR Imaging Improves the Differentiation of Breast Cancer Receptor Statuses Compared with Conventional Diffusion-Weighted Imaging. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging 2022, 56, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shahraki, Z.; Ghaffari, M.; Nakhaie Moghadam, M.; Parooie, F.; Salarzaei, M. Preoperative evaluation of breast cancer: Contrast-enhanced mammography versus contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Dis. 2022, 41, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, B.K.; Lobbes, M.B.I.; Lewin, J. Contrast Enhanced Spectral Mammography: A Review. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2018, 39, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogani, J.; Mango, V.L.; Keating, D.; Sung, J.S.; Jochelson, M.S. Contrast-enhanced mammography: Past, present, and future. Clin. Imaging 2021, 69, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tagliafico, A.S.; Bignotti, B.; Rossi, F.; Signori, A.; Sormani, M.P.; Valdora, F.; Calabrese, M.; Houssami, N. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast 2016, 28, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altabella, L.; Benetti, G.; Camera, L.; Cardano, G.; Montemezzi, S.; Cavedon, C. Machine learning for multi-parametric breast MRI: Radiomics-based approaches for lesion classification. Phys. Med. Biol. 2022, 67, 15TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y. Radiomics in breast cancer: Current advances and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1134567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martina Jaincy, D.E.; Pattabiraman, V. BCDCNN: Breast cancer deep convolutional neural network for breast cancer detection using MRI images. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parekh, V.S.; Jacobs, M.A. Integrated radiomic framework for breast cancer and tumor biology using advanced machine learning and multiparametric MRI. Npj Breast Cancer 2017, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, Y.; Duan, S.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Pan, S.; Cheng, W.; Xia, L.; Qi, X. Integrative radiomics clustering analysis to decipher breast cancer heterogeneity and prognostic indicators through multiparametric MRI. Npj Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, L.R.; Oseni, T.O.; Lehman, C.D.; Bahl, M. Pre-operative MRI in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ: Is MRI useful for identifying additional disease? Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 129, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcan, L.C.; Donovan, C.A.; Srour, M.; Chung, A.; Mirocha, J.; Frankel, S.D.; Hakim, P.; Giuliano, A.E.; Amersi, F. Invasive Lobular Carcinoma-Correlation Between Imaging and Final Pathology: Is MRI Better? Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 2600–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinker, K.; Moy, L.; Sutton, E.J.; Mann, R.M.; Weber, M.; Thakur, S.B.; Jochelson, M.S.; Bago-Horvath, Z.; Morris, E.A.; Baltzer, P.A.; et al. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging with Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Mapping for Breast Cancer Detection as a Stand-Alone Parameter: Comparison with Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced and Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Investig. Radiol. 2018, 53, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Feng, L.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, N.; Xie, Y. Comparison of Contrast-Enhanced Spectral Mammography and Contrast-Enhanced MRI in Screening Multifocal and Multicentric Lesions in Breast Cancer Patients. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 4224701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khazindar, A.R.; Hashem, D.A.L.; Abusanad, A.; Bakhsh, S.I.; Bin Mahfouz, A.; El-Diasty, M.T. Diagnostic Accuracy of MRI in Evaluating Response After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy in Operable Breast Cancer. Cureus 2021, 13, e15516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gelardi, F.; Ragaini, E.M.; Sollini, M.; Bernardi, D.; Chiti, A. Contrast-Enhanced Mammography versus Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boruah, D.K.; Konwar, N.; Gogoi, B.B.; Hazarika, K.; Ahmed, H. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and Apparent diffusion coefficient mapping in the characterization of Palpable breast lesions: A prospective observational study. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2023, 54, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Majidpour, M.; Beitollahi, A. Multi-objective feature selection of radiomics and deep learning features for breast cancer subtype detection. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 6789–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimiel Naranjo, I.; Gibbs, P.; Reiner, J.S.; Lo Gullo, R.; Sooknanan, C.; Thakur, S.B.; Jochelson, M.S.; Sevilimedu, V.; Morris, E.A.; Baltzer, P.A.T.; et al. Radiomics and Machine Learning with Multiparametric Breast MRI for Improved Diagnostic Accuracy in Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mann, R.M.; Cho, N.; Moy, L. Breast MRI: State of the Art. Radiology 2019, 292, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Ruiz, C.; Saidi, L.Z.; Zambrana Aguilar, L.; Moreira Cabrera, M.; Carvia Ponsaille, C.; Vázquez Sousa, R.; Martínez Porras, C.; Murillo-Cancho, A.F. Role of MRI in the Diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, R.M.; Hoogeveen, Y.L.; Blickman, J.G.; Boetes, C. MRI compared to conventional diagnostic work-up in the detection and evaluation of invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: A review of existing literature. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 107, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pereslucha, A.M.; Wenger, D.M.; Morris, M.F.; Aydi, Z.B. Invasive Lobular Carcinoma: A Review of Imaging Modalities with Special Focus on Pathology Concordance. Healthcare 2023, 11, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.M.; Kuhl, C.K.; Moy, L. Contrast-enhanced MRI for breast cancer screening. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019, 50, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Banisi, M.K.; Ghadri, H.; Soltani, B.; Farshid, A.; Behnam, B.; Rhouholamini, A.A.; Mohammadi, A.; Hamzavi, S.F.; Azizi, A.; Deravi, N.; et al. The effect of pre-operative MRI on the in-breast tumor recurrence rate of patients with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Langenbec. Arch. Surg 2025, 410, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.M.; Gilchrist, S.; Cordiner, C.; Dixon, J.M. The role of breast MRI in newly diagnosed breast cancer: An evidence-based review. Breast 2020, 49, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, V.; Accardo, G.; Perillo, T.; Basso, L.; Garbino, N.; Nicolai, E.; Maurea, S.; Salvatore, M. Assessment and Prediction of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer: A Comparison of Imaging Modalities and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2021, 13, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, R.; Zhu, M.; Chen, X. Diagnostic performance of mammography and magnetic resonance imaging for evaluating mammographically visible breast masses. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 300060520973092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pop, C.F.; Stanciu-Pop, C.; Drisis, S.; Radermeker, M.; Vandemerckt, C.; Noterman, D.; Moreau, M.; Larsimont, D.; Nogaret, J.M.; Veys, I. The impact of breast MRI workup on tumor size assessment and surgical planning in patients with early breast cancer. Breast J. 2018, 24, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.J.; Chae, E.Y.; Shin, H.J.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, H.H. The Role of Preoperative Breast MRI in Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Investig. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2025, 29, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, L.; Brown, S.; Harvey, I.; Olivier, C.; Drew, P.; Napp, V.; Hanby, A.; Brown, J. Comparative effectiveness of MRI in breast cancer (COMICE) trial: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 375, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, N.H.; van Esser, S.; van den Bosch, M.A.; Storm, R.K.; Plaisier, P.W.; van Dalen, T.; Diepstraten, S.C.; Weits, T.; Westenend, P.J.; Stapper, G.; et al. Preoperative MRI and surgical management in patients with nonpalpable breast cancer: The MONET-randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, D.; Newitt, D.C.; Wilmes, L.J.; Jones, E.F.; Kornak, J.; Hylton, N.M. Diffusion weighted imaging for improving the diagnostic performance of screening breast MRI: Impact of apparent diffusion coefficient quantitation methods and cutoffs. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2021, 54, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shu, J. Comparative analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) metrics for the differential diagnosis of breast mass lesions. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, A.G.V.; Pires, B.S.; Calsavara, V.F.; Negrão, E.M.S.; Souza, J.A.; Graziano, L.; Guatelli, C.S.; Makdissi, F.B.; Sanches, S.M.; Tavares, M.C.; et al. Prognostic value of response evaluation based on breast MRI after neoadjuvant treatment: A retrospective cohort study. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 9520–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesio, L.; Gigli, S.; Di Pastena, F.; Giraldi, G.; Manganaro, L.; Anastasi, E.; Catalano, C. Magnetic resonance imaging tumor regression shrinkage patterns after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced breast cancer: Correlation with tumor biological subtypes and pathological response after therapy. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317694540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gültürk, İ.; Güney, B.; Özge, E.; Han, Ö.; Ata, E.S.; Gürsu, R.U.; Ulusan, M.B.; Usul, Ç. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Predicting Pathological Complete Response in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Bagcilar Med. Bull. 2025, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannachi, L.; Gangeh, M.; Tadayyon, H.; Sadeghi-Naini, A.; Gandhi, S.; Wright, F.C.; Slodkowska, E.; Curpen, B.; Tran, W.; Czarnota, G.J. Response monitoring of breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy using quantitative ultrasound, texture, and molecular features. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kuhl, C.K. Abbreviated breast MRI for screening women with dense breast: The EA1141 trial. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, J.; Greuter, M.J.W.; Vermeulen, K.M.; Brokken, F.B.; Dorrius, M.D.; Lu, W.; de Bock, G.H. Cost-effectiveness of abbreviated-protocol MRI screening for women with mammographically dense breasts in a national breast cancer screening program. Breast 2022, 61, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Battaglia, O.; Pesapane, F.; Penco, S.; Signorelli, G.; Dominelli, V.; Nicosia, L.; Bozzini, A.C.; Rotili, A.; Cassano, E. Ultrafast Breast MRI: A Narrative Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; An, Y.; Mao, G. The value of MRI for downgrading of breast suspicious lesions detected on ultrasound. BMC Med. Imaging 2023, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, V.N.; Kusumaningtyas, N.; Supit, N.I.S.H.; Sanjaya, E.; Chandra, M.; Sulay, C.B.H.; Octavius, G.S. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy of Dynamic Contrast Enhancement and Diffusion-Weighted MRI in Differentiating Benign and Malignant Non-Mass Enhancement Lesions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Poplack, S. A review of optical breast imaging: Multi-modality systems for breast cancer diagnosis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 129, 109067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 59. Bechyna, S.; Santonocito, A.; Pötsch, N.; Clauser, P.; Helbich, T.H.; Baltzer, P.A.T. Impact of Background Parenchymal Enhancement (BPE) on diagnostic performance of Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) for breast cancer diagnosis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2025, 188, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subha, S.; Amudha Bhomini, P. A Comprehensive Review of Image-Based Breast Cancer Detection Techniques: Challenges and Perspectives. Oper. Res. Forum 2025, 6, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel, M.; Baltzer, P.A.T. How to use the Kaiser score as a clinical decision rule for diagnosis in multiparametric breast MRI: A pictorial essay. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Su, S.; Ray, J.C.; Ooi, C.; Jain, M. Pathology of MRI and second-look ultrasound detected multifocal breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajnc, D.; Papp, L.; Nakuz, T.S.; Magometschnigg, H.F.; Grahovac, M.; Spielvogel, C.P.; Ecsedi, B.; Bago-Horvath, Z.; Haug, A.; Karanikas, G.; et al. Breast Tumor Characterization Using [18F]FDG-PET/CT Imaging Combined with Data Preprocessing and Radiomics. Cancers 2021, 13, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerke, O. Reporting Standards for a Bland-Altman Agreement Analysis: A Review of Methodological Reviews. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fallenberg, E.M.; Dromain, C.; Diekmann, F.; Engelken, F.; Krohn, M.; Singh, J.M.; Ingold-Heppner, B.; Winzer, K.J.; Bick, U.; Renz, D.M. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography versus MRI: Initial results in the detection of breast cancer and assessment of tumour size. Eur. Radiol. 2014, 24, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggag, M.A.; Helal, M.H.; Kamal, R.M.; E Mostafa, R.; Salama, A.I.; E Hassan, A. Could new mammography techniques be an alternative for dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI in the diagnosis and preoperative staging of breast lesions? Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2025, 56, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekirçavuşoğlu, A.F.; Kul, S.; Bekirçavuşoğlu, S.; Atasoy, D.; Erkan, M. Evaluatıon of contrast enhancement intensity, pattern, and kinetics of breast lesions on contrast-enhanced spectral mammography. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2025, 56, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, K.; Jochelson, M.S. Contrast-enhanced mammography in breast cancer screening. Eur. J. Radiol. 2022, 156, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al Ewaidat, H.; Ayasrah, M. A Concise Review on the Utilization of Abbreviated Protocol Breast MRI over Full Diagnostic Protocol in Breast Cancer Detection. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2022, 2022, 8705531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Onishi, N.; Sadinski, M.; Hughes, M.C.; Ko, E.S.; Gibbs, P.; Gallagher, K.M.; Fung, M.M.; Hunt, T.J.; Martinez, D.F.; Shukla-Dave, A.; et al. Ultrafast dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI may generate prognostic imaging markers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martinez Luque, E.; Liu, Z.; Sung, D.; Goldberg, R.M.; Agarwal, R.; Bhattacharya, A.; Ahmed, N.S.; Allen, J.W.; Fleischer, C.C. An Update on MR Spectroscopy in Cancer Management: Advances in Instrumentation, Acquisition, and Analysis. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2024, 6, e230101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hernández, M.L.; Osorio, S.; Florez, K.; Ospino, A.; Díaz, G.M. Abbreviated magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer: A systematic review of literature. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2020, 8, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mango, V.L.; Morris, E.A.; David Dershaw, D.; Abramson, A.; Fry, C.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Hughes, M.; Kaplan, J.; Jochelson, M.S. Abbreviated protocol for breast MRI: Are multiple sequences needed for cancer detection? Eur. J. Radiol. 2015, 84, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhl, C.K.; Schrading, S.; Strobel, K.; Schild, H.H.; Hilgers, R.D.; Bieling, H.B. Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): First postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection-a novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2304–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, T.; Wu, Z.; Lin, Q.; Wang, H.; Ge, Y.; Duan, S.; Fu, G.; Cui, C.; Su, X. Radiomic signatures derived from multiparametric MRI for the pretreatment prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20200287, Erratum in Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, bjr20200287c. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20200287.c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Y. Development and Validation of an MRI Radiomics-Based Signature to Predict Histological Grade in Patients with Invasive Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2022, 14, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cain, E.H.; Saha, A.; Harowicz, M.R.; Marks, J.R.; Marcom, P.K.; Mazurowski, M.A. Multivariate machine learning models for prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer using MRI features: A study using an independent validation set. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 173, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aroney, N.; Koelmeyer, L.; Elder, E.; French, J.; Spillane, A. Preoperative breast MR imaging influences surgical management in patients with invasive lobular carcinoma. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 68, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poenaru, M.-O.; Amza, M.; Toma, C.-V.; Augustin, F.-E.; Pacu, I.; Zampieri, G.; Ples, L.; Sima, R.-M.; Diaconescu, A.-S. Multicentric and Multifocal Breast Tumors—Narrative Literature Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattar, A.; Antonini, M.; Amorim, A.; Mateus, E.F.; Bagnoli, F.; Cavalcante, F.P.; Novita, G.; Mori, L.J.; Madeira, M.; Diógenes, M.; et al. PROMRIINE (PRe-operatory Magnetic Resonance Imaging is INEffective) Study: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Impact of Magnetic Resonance Imaging on Surgical Decisions and Clinical Outcomes in Women with Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2024, 31, 8021–8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Zugai, K.; Georgiadou, I.; Weiss, C.; Ast, A.; Scheffel, H. The Impact of Preoperative Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging on Surgical Planning: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Anatomia 2025, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, X.; He, Y.; He, F.; Ren, J.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, X. Tumor size and stage assessment accuracy of MRI and ultrasound versus pathological measurements in early breast cancer patients. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, K. Preoperative MRI Improves Surgical Planning and Outcomes for Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. Radiology 2020, 295, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Melvin, Z.; Lim, D.; Jacques, A.; Falkner, N.M.; Lo, G. Is staging breast magnetic resonance imaging for invasive lobular carcinoma worthwhile? ANZ J. Surg. 2024, 94, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Du, S.; Gao, S.; Zhao, R.; Liu, S.; Jiang, W.; Peng, C.; Chai, R.; Zhang, L. MRI-based tumor shrinkage patterns after early neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer: Correlation with molecular subtypes and pathological response. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pediconi, F.; Speranza, A.; Moffa, G.; Maroncelli, R.; Coppola, S.; Galati, F.; Bernardi, C.; Maccagno, G.; Pugliese, D.; Catalano, C.; et al. Contrast-enhanced mammography for breast cancer detection and diagnosis with high concentration iodinated contrast medium. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochelson, M.S.; Lobbes, M.B.I. Contrast-enhanced Mammography: State of the Art. Radiology 2021, 299, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, B.K.; Hilal, T.; Covington, M.; Zhang, N.; Kosiorek, H.E.; Lobbes, M.; Northfelt, D.W.; Pockaj, B.A. Contrast-Enhanced Spectral Mammography is Comparable to MRI in the Assessment of Residual Breast Cancer Following Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausmann, D.; Todorski, I.; Pindur, A.; Weiland, E.; Benkert, T.; Bosshard, L.; Prummer, M.; Kubik-Huch, R.A. Advanced Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Sequences for Breast MRI: Comprehensive Comparison of Improved Sequences and Ultra-High B-Values to Identify the Optimal Combination. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottat, N.A.; Badr, D.A.; Lecomte, S.; Besse-Hammer, T.; Jani, J.C.; Cannie, M.M. Assessment of diffusion-weighted MRI in predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- American College of Radiology. ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Breast; ACR: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Design | Index Test | Reference Standard | Patient Selection Bias | MRI Protocol Bias | Flow/Timing Bias | Applicability (Clinical Context) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Houssami N et al., 2008 [9] | Systematic review and meta-analysis (19 studies, 2610 patients) | Preoperative MRI for multifocal/multicentric Breast Cancer | Histopathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Carmon E et al., 2022 [10] | Prospective (183 patients) | MRI in IDC vs. ILC | Histopathology | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Marinovich ML et al., 2013 [11] | Meta-analysis (44 studies, 2050 patients) | MRI for NAT response | Surgery/pathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Janssen LM et al., 2022 [12] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | MRI to assess response after NAC | Histopathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Altabella L et al., 2022 [19] | Review/state-of-the-art | mpMRI radiomics/AI | Literature-based | N/A | N/A | N/A | High |

| He Y et al., 2024 [23] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | MRI to assess response after NAT | Histopathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Lamb, L.R. et al., 2020 [24] | Retrospective cohort study | MRI in DCIS | Histopathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Ozcan et al., 2023 [25] | Cohort (126 ILC patients) | Preop MRI impact | Surgery/pathology | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Pinker K et al., 2018 [26] | Prospective (182 patients) | DWI/ADC mapping | Histopathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Feng L et al., 2022 [27] | Prospective (132 patients) | CEM vs. MRI | Histopathology | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Khazindar AR et al., 2021 [28] | Cohort (214 patients) | MRI post-NAT | Pathology | Moderate | Low | Low | High |

| Gelardi F et al., 2022 [29] | Systematic review and meta-analysis (17 studies) | CEM vs. MRI | Histopathology | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Boruah DK et al., 2023 [30] | Prospective (102 patients) | DCE-MRI + ADC mapping | Histopathology | Moderate | Low | Low | High |

| Majidpour M et al., 2025 [31] | Computational model (400 images) | Radiomics + DL features | Histopathologic subtypes | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Daimiel Naranjo I et al., 2021 [32] | Radiomics/ML study (960 patients) | mpMRI features | Histopathology | Low | Moderate | Low | High |

| Parameter | Typical Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MRI field strength | 1.5 T: ~65%; 3 T: ~35% | Higher field strength improves signal-to-noise ratio and lesion conspicuity |

| Sample size (per study) | Median 120 (range 45–520) | Reflects predominance of single-center cohorts |

| Dominant subtype | IDC: 60–70%; ILC: 15–20%; DCIS: 10–15% | Subtype composition influences MRI–pathology concordance |

| Neoadjuvant vs. upfront surgery | NAT: ~40%; Upfront: ~60% | mpMRI/DWI more frequent in NAT studies |

| Study design | Retrospective: ~70%; Prospective: ~30% | Prospective trials and meta-analyses formed the minority |

| Tumor Subtype/Factor | MRI Sensitivity (%) | MRI–Histopathology Concordance | Diagnostic Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC) | 83–100 | High | Accurate sizing |

| Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC) | 81–98 | Moderate | Overestimation; indistinct margins |

| Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS) | 70–90 | Low–Moderate | Overestimation; false positives |

| Tumor size < 2 cm | High | High | Good correlation |

| Tumor size > 3 cm | Variable | Lower | Overestimation risk |

| Early stage (T0–T1) | Lower | Low | Missed/underestimated lesions |

| Advanced stage (T2–T3) | Higher | High | Better-defined margins improve correlation |

| Low-grade tumors | Variable | Moderate | Heterogeneous enhancement |

| High-grade tumors | High | High | Strong contrast enhancement |

| Multifocal/multicentric | High | Moderate | False positives → overtreatment risk |

| Post-mastectomy with implant | High (near implant) | High | Implant/distortion artifacts |

| Post-mastectomy with flap | Moderate | Reduced | Deep residual disease may be missed |

| Neoadjuvant—HER2+ | High | Strong (concentric shrinkage) | Good pCR prediction |

| Neoadjuvant—Luminal A | Moderate | Weaker (mixed patterns) | Residual disease underestimation |

| Modality | Reported Sensitivity (%) | Reported Specificity (%) | Key Strengths | Main Limitations | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional MRI | IDC 83–100; ILC 81–98; DCIS 70–90 | 65–85 | Highest sensitivity for invasive carcinoma; excellent for staging multifocal/multicentric disease; widely validated | Overestimation in DCIS/ILC; variable concordance with histology; higher cost; limited accessibility | Recommended selectively (ILC, dense breasts, occult primaries, neoadjuvant monitoring) |

| Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (CEM) | 85–95 | 75–88 | Comparable sensitivity to MRI; superior specificity in dense breasts; faster, cheaper, more accessible | Ionizing radiation; iodine contrast contraindications; fewer longitudinal outcome data | Promising alternative for preoperative staging and dense breasts where MRI is not feasible |

| Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) | >90 (with DWI) | 80–85 | Improves specificity without loss of sensitivity; DWI refines characterization; ultrafast or abbreviated protocols improve feasibility; radiomics predictive of grade/subtype | Requires standardized protocols; technical complexity; limited multicenter validation | Potential future standard integrating predictive biomarkers and personalized oncology |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannakaki, A.-G.; Giannakaki, M.-N.; Baroutis, D.; Koura, S.; Papachatzopoulou, E.; Marinopoulos, S.; Daskalakis, G.; Dimitrakakis, C. Preoperative Breast MRI and Histopathology in Breast Cancer: Concordance, Challenges and Emerging Role of CEM and mpMRI. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3032. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233032

Giannakaki A-G, Giannakaki M-N, Baroutis D, Koura S, Papachatzopoulou E, Marinopoulos S, Daskalakis G, Dimitrakakis C. Preoperative Breast MRI and Histopathology in Breast Cancer: Concordance, Challenges and Emerging Role of CEM and mpMRI. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3032. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233032

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannakaki, Aikaterini-Gavriela, Maria-Nektaria Giannakaki, Dimitris Baroutis, Sophia Koura, Eftychia Papachatzopoulou, Spyridon Marinopoulos, Georgios Daskalakis, and Constantine Dimitrakakis. 2025. "Preoperative Breast MRI and Histopathology in Breast Cancer: Concordance, Challenges and Emerging Role of CEM and mpMRI" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3032. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233032

APA StyleGiannakaki, A.-G., Giannakaki, M.-N., Baroutis, D., Koura, S., Papachatzopoulou, E., Marinopoulos, S., Daskalakis, G., & Dimitrakakis, C. (2025). Preoperative Breast MRI and Histopathology in Breast Cancer: Concordance, Challenges and Emerging Role of CEM and mpMRI. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3032. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233032