Management Strategies for Isolated Orbital Floor Fractures: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes and Surgical Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

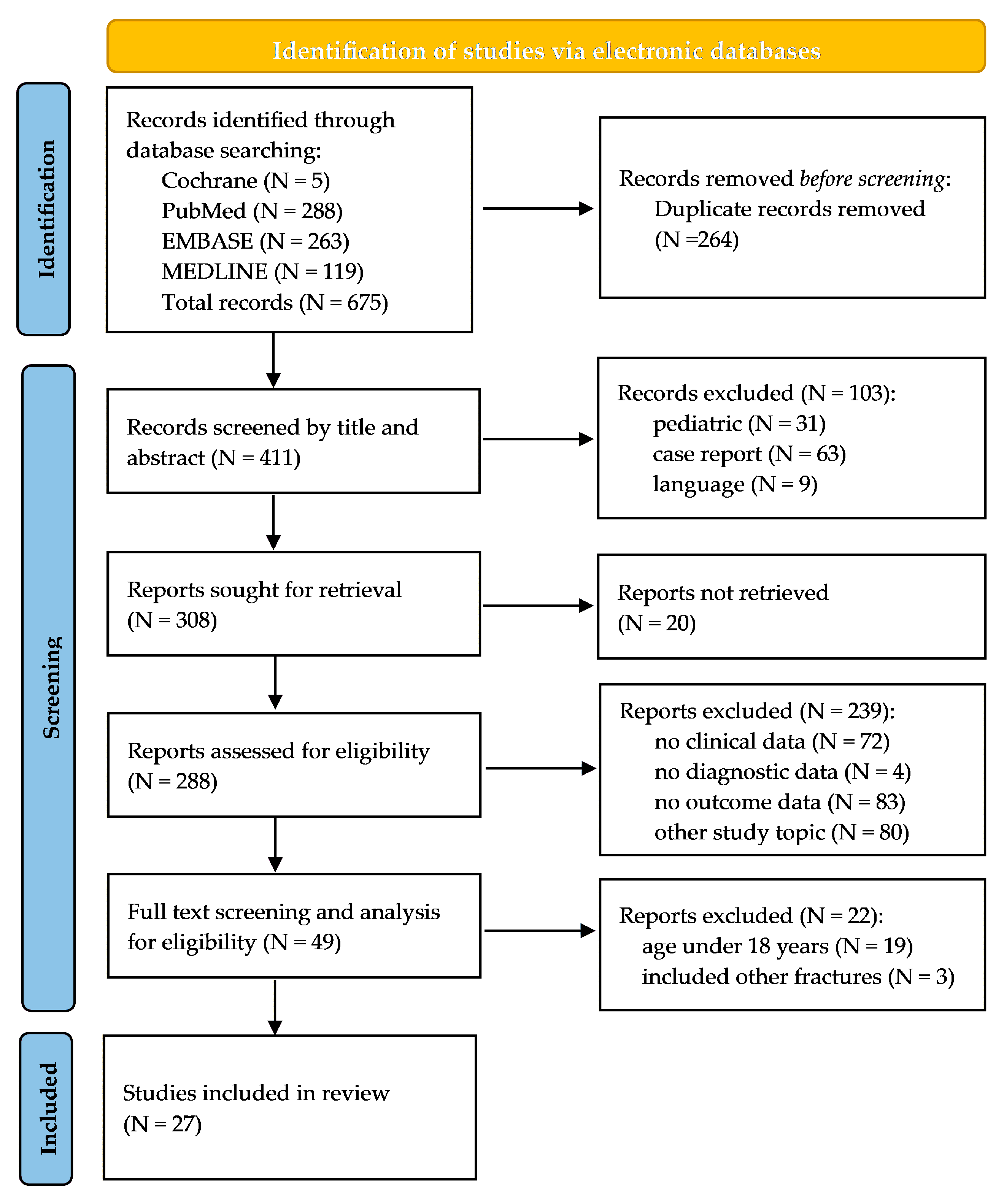

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| d | days |

| GWs | gunshot wounds |

| JBI | the Joanna Briggs Institute |

| m | months |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MVAs | motor vehicle accidents |

| No | number |

| NR | not reported |

| PDS | polydioxanone sheets |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| w | weeks |

| y | years |

Appendix A

| Source | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | |||||||||||

| Yano et al. (2010) [25] | |||||||||||

| Scolozzi et al. (2009) [26] | |||||||||||

| Ikeda et al. (1999) [27] | |||||||||||

| Prabhu et al. (2021) [28] | |||||||||||

| Fernandes et al. (2007) [29] | |||||||||||

| Scawn et al. (2016) [30] | |||||||||||

| Gugliotta et al. (2023) [31] | |||||||||||

| Worthington (2010) [32] | |||||||||||

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | |||||||||||

| O’Connell et al. (2015) [34] | |||||||||||

| Shah et al. (2013) [35] | |||||||||||

| Ishida et al. (2016) [36] | |||||||||||

| Ploder et al. (2003) [37] | |||||||||||

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] * | |||||||||||

| Soejima et al. (2013) [39] | |||||||||||

| Polligkeit et al. (2013) [40] | |||||||||||

| Homer et al. (2019) [41] | |||||||||||

| Abdelazem et al. (2020) [42] | |||||||||||

| Persons & Wong (2002) [43] | |||||||||||

| Jin et al. (2007) [44] | |||||||||||

| Ethunandan & Evans (2011) [45] | |||||||||||

| Al-Qattan & Al-Qattan (2021) [46] | |||||||||||

| Karthik et al. (2019) [47] | |||||||||||

| Sigron et al. (2020) [48] * | |||||||||||

| Emodi et al. (2018) [49] | |||||||||||

| Cheong et al. (2010) [50] |

References

- Antoun, J.S.; Lee, K.H. Sports-Related Maxillofacial Fractures Over an 11-Year Period. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; You, S.H.; Sohn, I.A. Analysis of orbital bone fractures: A 12-year study of 391 patients. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2009, 20, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigi, B.; Khandwala, M.; Gupta, D. Management of pure orbital floor fractures: A proposed protocol to prevent unnecessary or early surgery. Orbit 2014, 33, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, G.D.; Soon Ang, G.; Kempster, R.; Beigi, B. A review of the management of orbital floor fractures with a suggested management. CME J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 7, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, L.; Bauer, R.J.; Buchman, S.R. A current 10-year retrospective survey of 199 surgically treated orbital floor fractures in a nonurban tertiary care center. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, L.B.; Mainka, T.; Herrera-Vizcaino, C.; Verboket, R.; Sader, R. Orbital floor fractures: Epidemiology and outcomes of 1594 reconstructions. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahlieli, O.; Bar-Droma, E.; Zagury, A.; Turner, M.D.; Yoffe, B.; Shacham, R.; Bar, T. Endoscopic Intraoral Plating of Orbital Floor Fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnstine, M.A. Clinical recommendations for repair of isolated orbital floor fractures: An evidence-based analysis. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carinci, F.; Zollino, I.; Arduin, L.; Brunelli, G.; Pagliaro, F.; Cenzi, R. Midfacial fractures: A scoring method and validation on 117 patients. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2008, 34, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgouli, T.; Pountos, I.; Chang, B.Y.P.; Giannoudis, P.V. Prevalence of ocular and orbital injuries in polytrauma patients. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2011, 37, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.; Tan, Y. Assessment of internal orbital reconstructions for pure blowout fractures: Cranial bone grafts versus titanium mesh. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malara, P.; Malara, B.; Drugacz, J. Characteristics of maxillofacial injuries resulting from road traffic accidents—A 5-year review of the case records from Department of Maxillofacial Surgery in Katowice, Poland. Head Face Med. 2006, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchel, P.; Rahal, A.; Seto, I.; Iizuka, T. Reconstruction of orbital floor fracture with polyglactin 910/polydioxanon patch (Ethisorb): A retrospective study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 63, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.; Moos, K.F.; El-Attar, A. Ten years of mandibular fractures: An analysis of 2137 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1985, 59, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmäl, F.; Basel, T.; Grenzebach, U.H.; Thiede, O.; Stoll, W. Preseptal transconjunctival approach for orbital floor fracture repair: Ophthalmologic results in 209 patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006, 126, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducic, Y.; Verret, D.J. Endoscopic transantral repair of orbital floor fractures. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2009, 140, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermer, R.W.; Orban, R.E. Repair of orbital floor fractures with absorbable gelatin film. J. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma 1995, 1, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palavalli, M.H.; Huayllani, M.T.; Gokun, Y.; Lu, Y.; Janis, J.E. Surgical approaches to orbital fractures: A practical and systematic review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2023, 11, e4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, H.; Nakano, M.; Anraku, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Ishida, H.; Murakami, R.; Hirano, A. A consecutive case review of orbital blowout fractures and recommendations for comprehensive management. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 124, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosse, E.M.; Ferguson, A.W.; Lymburn, E.G.; Gilmour, C.; MacEwen, C.J. Blow-out fractures: Patterns of ocular motility and effect of surgical repair. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 48, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everhard-Halm, Y.S.; Koornneef, L.; Zonneveld, F.W. Conservative therapy frequently indicated in blow-out fractures of the orbit. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 1991, 135, 1226–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Pansell, T.; Alinasab, B.; Westermark, A.; Beckman, M.; Abdi, S. Ophthalmologic Findings in Patients with Non-Surgically Treated Blowout Fractures. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2012, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews: Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. In Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yano, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshimoto, H.; Mimasu, R.; Hirano, A. Linear-type orbital floor fracture with or without muscle involvement. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2010, 21, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolozzi, P.; Momjian, A.; Heuberger, J.; Andersen, E.; Broome, M.M.; Terzic, A.M.; Jaques, B.M. Accuracy and predictability in use of ao three-dimensionally preformed titanium mesh plates for posttraumatic orbital reconstruction: A pilot study. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2009, 20, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K.; Suzuki, H.; Oshima, T.; Takasaka, T. Endoscopic endonasal repair of orbital floor fracture. Arch. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 1999, 125, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.S.; Hemal, K.; Runyan, C.M. Outcomes in Orbital Floor Trauma: A Comparison of Isolated and Zygomaticomaxillary-Associated Fractures. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2021, 32, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, R.; Fattahi, T.; Steinberg, B.; Schare, H. Endoscopic Repair of Isolated Orbital Floor Fracture with Implant Placement. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1449–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scawn, R.L.; Lim, L.H.; Whipple, K.M.; Dolmetsch, A.; Priel, A.; Korn, B.M.; Kikkawa, D.O.M. Outcomes of Orbital Blow-Out Fracture Repair Performed beyond 6 Weeks after Injury. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 32, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliotta, Y.; Roccia, F.; Demo, P.G.; Rossi, M.B. Characteristics and surgical management of pure trapdoor fracture of the orbital floor in adults: A 15-year review. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 27, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, J.P. Isolated posterior orbital floor fractures, diplopia and oculocardiac reflexes: A 10-year review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 48, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, W.; Seidel, D.; Bredehorn-Mayr, T.; Eckert, A.W. Reconstruction of isolated orbital floor fractures with a prefabricated titanium mesh. Klin. Monbl. Augenheilkd. 2014, 231, 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, J.E.; Hartnett, C.; Hickey-Dwyer, M.; Kearns, G.J. Reconstruction of orbital floor blow-out fractures with autogenous iliac crest bone: A retrospective study including maxillofacial and ophthalmology perspectives. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.A.; Shipchandler, T.Z.; Sufyan, A.S.; Nunery, W.R.; Lee, H.B.H. Use of fracture size and soft tissue herniation on computed tomography to predict diplopia in isolated orbital floor fractures. Am. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Med. Surg. 2013, 34, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Kitaguchi, Y.; Kakizaki, H. Orbital floor thickness in adult patients with isolated orbital floor fracture lateral to the infraorbital nerve. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2016, 27, e638–e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploder, O.; Oeckher, M.; Klug, C.; Voracek, M.; Wagner, A.; Burggasser, G.; Baumann, A.; Czerny, C. Follow-up study of treatment of orbital floor fractures: Relation of clinical data and software-based CT-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 32, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigron, G.R.; Barba, M.; Chammartin, F.; Msallem, B.; Berg, B.-I.; Thieringer, F.M. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (Blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soejima, K.; Shimoda, K.; Kashimura, T.; Yamaki, T.; Kono, T.; Sakurai, H.; Nakazawa, H. Endoscopic transmaxillary repair of orbital floor fractures: A minimally invasive treatment. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2013, 47, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polligkeit, J.; Grimm, M.; Peters, J.P.; Cetindis, M.; Krimmel, M.; Reinert, S. Assessment of indications and clinical outcome for the endoscopy-assisted combined subciliary/transantral approach in treatment of complex orbital floor fractures. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 41, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, N.; Glass, L.R.; Lee, N.G.; Lefebvre, D.R.; Sutula, F.C.; Freitag, S.K.; Yoon, M.K. Assessment of Infraorbital Hypesthesia Following Orbital Floor and Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures Using a Novel Sensory Grading System. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 35, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelazem, M.H.; Erdogan, Ö.; Awad, T.A. A modified endoscopic technique for the repair of isolated orbital floor fractures. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2020, 43, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persons, B.L.; Wong, G.B. Transantral endoscopic orbital floor repair using resorbable plate. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2002, 13, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.R.; Yeon, J.Y.; Shin, S.O.; Choi, Y.; Lee, D. Endoscopic versus external repair of orbital blowout fractures. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2007, 136, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethunandan, M.; Evans, B.T. Linear trapdoor or “white-eye” blowout fracture of the orbit: Not restricted to children. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 49, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qattan, M.M.; Al-Qattan, Y.M. “Trap Door” Orbital Floor Fractures in Adults: Are They Different from Pediatric Fractures? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthik, R.; Cynthia, S.; Vivek, N.; Saravanan, C.; Prashanthi, G. Intraoperative Findings of Extraocular Muscle Necrosis in Linear Orbital Trapdoor Fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 1229.e1–1229.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigron, G.R.; Rüedi, N.; Chammartin, F.; Meyer, S.; Msallem, B.; Kunz, C.; Thieringer, F.M. Three-dimensional analysis of isolated orbital floor fractures pre-and post-reconstruction with standard titanium meshes and “hybrid” patient-specific implants. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emodi, O.; Nseir, S.; Shilo, D.; Srouji, H.D.; Rachmiel, A.D. Antral wall approach for reconstruction of orbital floor fractures using anterior maxillary sinus bone grafts. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2018, 29, e421–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, E.C.; Chen, C.T.; Chen, Y.R. Broad application of the endoscope for orbital floor reconstruction: Long-term follow-up results. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalloo, R.; Lucchesi, L.R.; Bisignano, C.; Castle, C.D.; Dingels, Z.V.; Fox, J.T.; Hamilton, E.B.; Liu, Z.; Roberts, N.L.S.; Sylte, D.O.; et al. Epidemiology of facial fractures: Incidence, prevalence and years lived with disability estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study. Inj. Prev. 2020, 26, i27–i35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Xie, L.; Li, Z. Global, regional, and national burdens of facial fractures: A systematic analysis of the global burden of Disease 2019. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; He, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D. Global, regional, and national burden of incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for facial fractures from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, S.; Committeri, U.; Barone, S.; Gentile, D.; Arena, A.; Salzano, G.; Bonavolontà, P.; Abbate, V.; Romano, A.; Dell’Aversana Orabona, G.; et al. Epidemiological analysis of patients with isolated blowout fractures of the orbital floor: Correlation between demographic characteristics and fracture area. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2024, 52, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeschl, P.W.; Baumann, A.; Dorner, G.; Russmueller, G.; Seemann, R.; Fabian, F.; Ewers, R. Functional outcome after surgical treatment of orbital floor fractures. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 16, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, P.; Mehanna, D.; Cronin, A. White-eyed blowout fracture: Another look: Case Report. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2009, 21, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasileiro, B.F.; van Sickels, J.E.; Cunningham, L.L. Oculocardiac reflex in an adult with a trapdoor orbital floor fracture: Case report, literature review, and differential diagnosis. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucoli, M.; Arcuri, F.; Cavenaghi, R.; Benech, A. Analysis of complications after surgical repair of orbital fractures. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2011, 22, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.R.; Lee, L.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Chien, K.H. Early intervention in orbital floor fractures: Postoperative ocular motility and diplopia outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Canto, A.J.; Linberg, J.V. Comparison of orbital fracture repair performed within 14 days versus 15 to 29 days after trauma. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 24, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, A.; Ewers, R. Use of the preseptal transconjunctival approach in orbit reconstruction surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 59, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhim, C.H.; Scholz, T.; Salibian, A.; Evans, G.R.D. Orbital Floor Fractures: A Retrospective Review of 45 Cases at a Tertiary Health Care Center. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2010, 3, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, P.M.; Monje, F.; Morillo, A.J.; Junquera, L.M.; González, C.; Barbón, J.J. Porous polyethylene implants in orbital floor reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002, 109, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.H.; Kim, J.G.; Moon, J.H.; Cho, J.H. Clinical analysis of surgical approaches for orbital floor fractures. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2008, 10, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakibuchi, M.; Fukazawa, K.; Fukuda, K.; Yamada, N.; Matsuda, K.; Kawai, K.; Tomofuji, S.; Sakagami, M. Combination of transconjunctival and endonasal-transantral approach in the repair of blowout fractures involving the orbital floor. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2004, 57, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakakibara, S.; Hashikawa, K.; Terashi, H.; Tahara, S. Reconstruction of the Orbital Floor with Sheets of Autogenous Iliac Cancellous Bone. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Converse, J.M.; Smith, B.; Obear, M.F.; Wood-Smith, D. Orbital blowout fractures: A ten-year survey. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1967, 39, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Abramson, M. Membranous vs. Endochondral Bone Autografts. Arch. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 1974, 99, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Bartlett, S.P.; Yaremchuk, M.J.; Fallon, M.; Grossman, R.F.; Whitaker, L.A. The effect of rigid fixation on the survival of onlay bone grafts: An experimental study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 86, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Hubschman, S.; Goldberg, R. Resorbable Implants for Orbital Fractures: A Systematic Review. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 81, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.A.; Brady, J.M.; Cutright, D.E. Degradation rates of oral resorbable implants (polylactates and polyglycolates): Rate modification with changes in PLA/PGA copolymer ratios. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1977, 11, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, E.; Messo, E. Use of nonresorbable alloplastic implants for internal orbital reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.K.; Ellis, E. Biomaterials for reconstruction of the internal orbit. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 1280–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, C.W. Alloplast materials in orbital repair. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1967, 63, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polley, J.W.; Ringler, S.L. The use of teflon in orbital floor reconstruction following blunt facial trauma: A 20-year experience. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1987, 79, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghaus, A. Porous Polyethylene in Reconstructive Head and Neck Surgery. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1985, 111, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, M.; Flemming, W.R.; Sauer, B.W. Early tissue infiltrate in porous polyethylene implants into bone: A scanning electron microscope study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1975, 9, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.J.; Iliff, N.T.; Manson, P.N. Use of medpor porous polyethylene implants in 140 patients with facial fractures. J. Craniofacial Surg. 1993, 4, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, W.R.; Wellisz, T. Scientific foundations: The natural history of alloplastic implants in orbital floor reconstruction: An animal model. J. Craniofacial Surg. 1994, 5, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consorti, G.; Betti, E.; Catarzi, L. Customized and Navigated Primary Orbital Fracture Reconstruction: Computerized Operation Neuronavigated Surgery Orbital Recent Trauma (CONSORT) Protocol. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seen, S.; Young, S.; Lang, S.S.; Lim, T.-C.; Amrith, S.; Sundar, G. Orbital implants in orbital fracture reconstruction: A ten-year series. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2020, 14, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.A.; Aum, J.H.; Kang, D.H.; Gu, J.H. Change of the orbital volume ratio in pure blow-out fractures depending on fracture location. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2013, 24, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msallem, B.; Sharma, N.; Cao, S.; Halbeisen, F.S.; Zeilhofer, H.-F.; Thieringer, F.M. Evaluation of the dimensional accuracy of 3D-printed anatomical mandibular models using FFF, SLA, SLS, MJ, and BJ printing technology. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D.M.; Chance, D.; Schmitt, S.; Mathis, J. An opinion survey of reported benefits from the use of stereolithographic models. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1999, 57, 1040–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.; Schreurs, R.; Dubois, L.; Maal, T.J.; Gooris, P.J.; Becking, A.G. The advantages of advanced computer-assisted diagnostics and three-dimensional preoperative planning on implant position in orbital reconstruction. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakiewicz, M.; Elgalal, M.; Piotr, L.; Broniarczyk-Loba, A.; Stefanczyk, L. Treatment with individual orbital wall implants in humans—1-year ophthalmologic evaluation. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 39, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerer, R.M.; Ellis, E.; Aniceto, G.S.; Schramm, A.; Wagner, M.E.; Grant, M.P.; Cornelius, C.-P.; Strong, E.B.; Rana, M.; Chye, L.T.; et al. A prospective multicenter study to compare the precision of posttraumatic internal orbital reconstruction with standard preformed and individualized orbital implants. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 44, 1485–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Jeong, W.S.; Park, T.; Choi, J.W.; Koh, K.S.; Oh, T.S. The accuracy of patient specific implant prebented with 3D-printed rapid prototype model for orbital wall reconstruction. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, R.; Metzger, M.C.; Zizelmann, C.; Weyer, N.; Schmelzeisen, R. Individually preformed titanium mesh implants for a true-to-original repair of orbital fractures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y.J.; Wang, B.F.; Che, L.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, G.Y. Clinical effects of 3-D printing-assisted personalized reconstructive surgery for blowout orbital fractures. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2017, 255, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.G.T.; Campbell, D.I.; Clucas, D.M. Rapid Prototyping Technology in Orbital Floor Reconstruction: Application in Three Patients. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2014, 7, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, A.B.; Campbell, A.A.; Petris, C.; Kazim, M. Low-Cost 3D Printing Orbital Implant Templates in Secondary Orbital Reconstructions. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 33, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, S.F.; Evans, P.L.; Bocca, A.; Patton, D.; Sugar, A.; Baxter, P. Customized titanium reconstruction of post-traumatic orbital wall defects: A review of 22 cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 40, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msallem, B.; Beiglboeck, F.; Honigmann, P.; Jaquiéry, C.; Thieringer, F. Craniofacial Reconstruction by a Cost-Efficient Template-Based Process Using 3D Printing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legocki, A.T.; Duffy-Peter, A.; Scott, A.R. Benefits and limitations of entry-level 3-dimensional printing of maxillofacial skeletal models. JAMA Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, E.B.; Fuller, S.C.; Wiley, D.F.; Zumbansen, J.; Wilson, M.D.; Metzger, M.C. Preformed vs. Intraoperative Bending of Titanium Mesh for Orbital Reconstruction. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2013, 149, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, M.C.; Schön, R.; Weyer, N.; Rafii, A.; Gellrich, N.-C.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Strong, B.E. Anatomical 3-dimensional Pre-bent Titanium Implant for Orbital Floor Fractures. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 1863–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Bandopadhyay, M.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Biswas, S.; Saha, A.; Balkrishna, U.M.; Nair, V. Clinical evaluation of neurosensory changes in the infraorbital nerve following surgical management of zygomatico-maxillary complex fractures. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZC54–ZC58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquiéry, C.; Aeppli, C.; Cornelius, P.; Palmowsky, A.; Kunz, C.; Hammer, B. Reconstruction of orbital wall defects: Critical review of 72 patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 36, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Study Design | Patients [No.] | Patient Age, Mean and Range [y] | Sex, Male/Female [No.] | Year of Observation | Average/Range of Follow-Up Duration | Treatment Conservatively/Surgical [No.] | Average Time to Intervention | Surgical Approach | Method of Reconstruction (No. of Cases) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | retrospective | 5 | 36.6, 24–47 | 5/0 | NR | 2–12 m | 0/5 | 2 w | endoscopic transmaxillary | Titanium mesh implant (Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland) |

| Yano et al. (2010) [25] | retrospective | 2 | 24.3, 18.8 | 2/0 | 2002–2007 | NR | 0/2 | 9 d | subciliary | Bone graft |

| Scolozzi et al. (2009) [26] | prospective | 7 | 41.5, 21–71 | 5/2 | 05.2007–01.2008 | 6 w–9 m | 0/7 | NR | transconjunctival | Titanium mesh (MatrixORBITAL, Synthes, Switzerland) |

| Ikeda et al. (1999) [27] | retrospective | 6 | 31.5, 26–38 | 5/1 | 09.1994–06.1997 | 6 m | 0/6 | 2 w (2) 3 w (4) | endoscopic endonasal | Balloon catheter |

| Prabhu et al. (2021) [28] | retrospective | 75 | 37.9 | NR | 2012–2019 | 20 w | 0/75 | 3–14 d | Transconjunctival (49), transcutaneous (23), prior laceration (3) | NR |

| Fernandes et al. (2007) [29] | prospective | 10 | 37.3, 19–47 | 7/3 | 06.2005–12.2005 | 12.7 w 1–26 w | 0/10 | 10.9 d, 3–36 d | endoscopic transmaxillary | Medpor® implant |

| Scawn et al. (2016) [30] | retrospective | 10 | 55.1, 25–80 | NR | 04.2008–01.2014 | 8 m, 6 w–56 m | 0/10 | 7 w–21 y | transconjunctival | Medpor® implant (8), Nylon Foil (2) |

| Gugliotta et al. (2023) [31] | retrospective | 18 | 25.3, 18–47 | 12/6 | 01.2006–12.2020 | 6 m | 0/18 | 3.8 d, 0–17 | transconjunctival, subciliary | Lyoplant® |

| Worthington (2010) [32] | retrospective | 5 | 21.2, 19–23 | 5/0 | 1997–2007 | 3.7 m, 2–6 m | 0/5 | 24–48 h | NR | Titanium mesh |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | prospective | 10 | 26–83 | 8/2 | 06.2011–11.2013 | 6 m | 0/10 | NR | subciliary (3), transconjunctival (4), mediopalpebral (2), transmaxillary (1) | Titanium mesh (Matrix MIDFACE, Synthes, Switzerland) |

| O’Connell et al. (2015) [34] | retrospective | 20 | 29, 19–57 | 18/2 | 10 years | 26 m, 2–120 m | 0/20 | 11 d, 5–19 d | subciliary | Autogenous iliac crest bone |

| Shah et al. (2013) [35] | retrospective | 56 | NR | NR | 03.2009–03.2012 | 6 w | 16/40 | 12 d, 1–37 d | NR | NR |

| Ishida et al. (2016) [36] | retrospective | 5 | 39.6, 19–67 | 3/2 | 03.2005–04.2016 | NR | 2/3 | NR | NR | NR |

| Ploder et al. (2003) [37] | retrospective | 30 | 45.3, 22–70 | 22/8 | 01.2000–12.2001 | 12 w | 10/20 | 5.6 d, 2.1–9.1 d | endoscopic endonasal (11), endoscopic endonasal & transconjunctival (9) | Balloon catheter (11), balloon catheter & Ethisorb® patch (9) |

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] * | retrospective | 30 | 51.2, 20–91 | 15/15 | 05.2016–11.2018 | 6 m | 0/30 | 4.1 ± 3.1 d (13) 4.2 ± 5.2 d (17) | mid-eyelid (28), transconjunctival (1), laceration (1) | Titanium conventional (13) & preformed titanium mesh implant (17), (MatrixMIDFACE, Synthes, Switzerland or MODUS OPS 1.5, Medartis, Switzerland) |

| Soejima et al. (2013) [39] | retrospective | 30 | 19–75 | 21/9 | 06.2006–11.2011 | 6 m | 0/30 | 13.9 d, 10.3–17.5 d | endoscopic transmaxillary | Balloon catheter |

| Polligkeit et al. (2013) [40] | prospective | 13 | 43.2, 18–82 | 7/6 | 02.2009–08.2012 | NR | 0/13 | 9.4 d, 3.6–15.2 d | combined endoscopic transmaxillary, subciliary | PDS™ sheets (7), preformed titanium implants (3), (MatrixORBITAL Synthes, Switzerland) Ethisorb® patch (3) |

| Homer et al. (2019) [41] | retrospective | 22 | 47.1 | 16/6 | 01.2015–04.2016 | 21 m | 14/8 | NR | NR | NR |

| Abdelazem et al. (2020) [42] | prospective | 5 | 31 | 4/1 | NR | 3 m | 0/5 | NR | endoscopic transmaxillary | Titanium mesh implant (Stryker, USA) |

| Persons & Wong (2002) [43] | retrospective | 5 | 18–41 | 4/1 | NR | 3 m–1 y | 0/5 | NR | endoscopic transmaxillary | LactoSorb® |

| Jin et al. (2007) [44] | retrospective | 45 | 30 | 76/24% | 1992–2004 | 3 m–4 y | 0/45 | 0–7 (4), 8–14 (26), 15–21 (8), >22 (7) | endoscopic endonasal (1), transmaxillary (16), external (28) | Balloon catheter, Medpor® implant |

| Ethunandan & Evans (2011) [45] | retrospective | 3 | 21–53 | 2/1 | NR | 5.1 m | 0/3 | 12.3 d | transcutaneous, transconjunctival | MacroPore® implant |

| Al-Qattan & Al-Qattan (2021) [46] | retrospective | 7 | 35, 25–50 | 7/0 | 20 y | 11 m, 6–16 m | 0/7 | <2 d | infraorbital | Titanium mesh |

| Karthik et al. (2019) [47] | retrospective | 3 | 24–29 | 2/1 | 06.2012–01.2017 | 12 m | 0/3 | <6 d | subciliary, endoscopic endonasal | NR |

| Sigron et al. (2020) [48] * | retrospective | 22 | 49.8, 20–83 | 12/10 | 05.2016–11.2018 | 6 m | 0/22 | 4.1 ± 3.1 d (12) 2.8 ± 2.5 d (10) | mid-eyelid, transconjunctival, transcaruncular | Freehand (12) & pre-bent patient-specific titanium mesh implant (10), (MatrixMIDFACE, Synthes, Switzerland or MODUS OPS 1.5, Medartis, Switzerland) |

| Emodi et al. (2018) [49] | retrospective | 9 | 32.7, 24–48 | 7/2 | 2008–2016 | 1–3 y | 0/9 | 1–4 d | combined transmaxillary and midtarsal (4), subciliary (3), infraorbital (2) + intraoral | Maxillary antral bone grafts |

| Cheong et al. (2010) [50] | retrospective | 13 | 21.15, 18–38 | 9/7 | 04.1998–06.2008 | 27.5 m, 4 m–10 y | 0/13 | 1–5 d (6), 8–11 d (2), 23–95 (4), 5 y (1) | endoscopic transmaxillary | Titanium micromesh (7) Medpor® implant (5), NR (1) |

| Source | Mean Duration [min] | Method of Reconstruction | Surgical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | 60–120 | titanium mesh implant | endoscopic transmaxillary |

| Fernandes et al. (2007) [29] | 70–80 | Medpor implant | endoscopic transmaxillary |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | 82 | balloon catheter | transmaxillary |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | 79 | PDS sheets | subciliary, transconjunctival, mediopalpebral, wound |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | 110 | preformed titanium mesh implant | |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | 76 | others | combination |

| Sigron et al. (2020) [48] | 99.8 ± 28.9 | freehand bent titanium mesh implant | mid-eyelid, transconjunctival, transcaruncular |

| Sigron et al. (2020) [48] | 57.3 ± 23.4 | pre-bent patient-specific titanium mesh implant | mid-eyelid, transconjunctival, transcaruncular |

| Source | Location | Assault [No.] | MVAs [No.] | Work [No.] | Sport [No.] | Blunt Trauma [No.] | Fall [No.] | GWs [No.] | Others [No.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | Israel | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yano et al. (2010) [25] | Japan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ikeda et al. (1999) [27] | Japan | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prabhu et al. (2021) [28] | USA | 26 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| Fernandes et al. (2007) [29] | USA | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gugliotta et al. (2023) [31] | Italy | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Worthington (2010) [32] | New Zealand | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | Germany | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| O’Connell et al. (2015) [34] | Ireland | 8 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ishida et al. (2016) [36] | Japan | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Ploder et al. (2003) [37] | Austria | 12 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] | Switzerland | 9 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Soejima et al. (2013) [39] | Japan | 12 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdelazem et al. (2020) [42] | Egypt | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethunandan & Evans (2011) [45] | United Kingdom | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Al-Qattan & Al-Qattan (2021) [46] | Saudi Arabia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Karthik et al. (2019) [47] | India | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Assault | MVAs | Work | Sport | Blunt trauma | Fall | GWs | Others | ||

| TOTAL [No.] | 268 | 94 | 37 | 3 | 51 | 21 | 58 | 1 | 3 |

| TOTAL [%] | 35.1 | 13.8 | 1.1 | 19.0 | 7.9 | 21.6 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Source | Patients [No.] | Preoperative Enophthalmos [No.] | Postoperative Enophthalmos [No.] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Scolozzi et al. (2009) [26] | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Ikeda et al. (1999) [27] | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Prabhu et al. (2021) [28] | 75 | 36 | 7 |

| Scawn et al. (2016) [30] | 10 | 7 | 0 |

| O’Connell et al. (2015) [34] | 20 | 2 | 1 |

| Ishida et al. (2016) [36] | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] | 30 | 6 | 1 |

| Soejima et al. (2013) [39] | 30 | 4 | 1 |

| Polligkeit et al. (2013) [40] | 13 | 2 | 0 |

| Jin et al. (2007) [44] | 17 (endoscopic) | 4 | 0 |

| Jin et al. (2007) [44] | 28 (external) | 10 | 3 |

| Karthik et al. (2019) [47] | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Cheong et al. (2010) [50] | 13 | 8 | 0 |

| TOTAL [No.] | 262 | 88 | 13 |

| TOTAL [%] | 33.6 | 5.0 | |

| Persistence rate after surgery [%] | 14.8 | ||

| Resolution rate after surgery [%] | 85.2 |

| Source | Patients [No.] | Preoperative Diplopia [No.] | Postoperative Diplopia [No.] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| Yano et al. (2010) [25] | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Scolozzi et al. (2009) [26] | 7 | 5 | 1 |

| Prabhu et al. (2021) [28] | 75 | 38 | 13 |

| Fernandes et al. (2007) [29] | 10 | 9 | 0 |

| Scawn et al. (2016) [30] | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| Worthington (2010) [32] | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Reich et al. (2014) [33] | 10 | 10 | 3 |

| O’Connell et al. (2015) [34] | 20 | 19 | 3 |

| Shah et al. (2013) [35] | 56 | 19 | 4 |

| Ishida et al. (2016) [36] | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Ploder et al. (2003) [37] | 30 | 18 | 1 |

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] | 30 | 19 | 8 |

| Soejima et al. (2013) [39] | 30 | 30 | 2 |

| Polligkeit et al. (2013) [40] | 13 | 8 | 6 |

| Abdelazem et al. (2020) [42] | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Persons & Wong (2002) [43] | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Jin et al. (2007) [44] | 17 (endoscopic) | 15 | 7 |

| Jin et al. (2007) [44] | 28 (external) | 22 | 13 |

| Ethunandan & Evans (2011) [45] | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Al-Qattan & Al-Qattan (2021) [46] | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Karthik et al. (2019) [47] | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Emodi et al. (2018) [49] | 9 | 5 | 0 |

| Cheong et al. (2010) [50] | 13 | 7 | 2 |

| TOTAL [No.] | 398 | 262 | 66 |

| TOTAL [%] | 65.8 | 16.6 | |

| Persistence rate after surgery [%] | 25.2 | ||

| Resolution rate after surgery [%] | 74.8 |

| Source | Patients [No.] | Preoperative Hypoesthesia [No.] | Postoperative Hypoesthesia [No.] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Yano et al. (2010) [25] | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ikeda et al. (1999) [27] | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Scawn et al. (2016) [30] | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] | 30 | 14 | 7 |

| Homer et al. (2019) [41] | 22 | 7 | 2 |

| Ethunandan & Evans (2011) [45] | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| TOTAL [No.] | 78 | 36 | 14 |

| TOTAL [%] | 46.2 | 17.9 | |

| Persistence rate after surgery [%] | 38.9 | ||

| Resolution rate after surgery [%] | 61.1 |

| Source | Patients [No.] | Preoperative Motility Restriction [No.] | Postoperative Motility Restriction [No.] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nahlieli et al. (2007) [7] | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Yano et al. (2010) [25] | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Ikeda et al. (1999) [27] | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Prabhu et al. (2021) [28] | 75 | 45 | 23 |

| Scawn et al. (2016) [30] | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Sigron et al. (2021) [38] | 30 | 14 | 4 |

| Polligkeit et al. (2013) [40] | 13 | 7 | 4 |

| Abdelazem et al. (2020) [42] | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Ethunandan & Evans (2011) [45] | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Karthik et al. (2019) [47] | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| TOTAL [No.] | 156 | 86 | 33 |

| TOTAL [%] | 55.1 | 21.2 | |

| Persistence rate after surgery [%] | 38.4 | ||

| Resolution rate after surgery [%] | 61.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miran, B.; Toneatti, D.J.; Schaller, B.; Kalaitsidou, I. Management Strategies for Isolated Orbital Floor Fractures: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes and Surgical Approaches. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233024

Miran B, Toneatti DJ, Schaller B, Kalaitsidou I. Management Strategies for Isolated Orbital Floor Fractures: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes and Surgical Approaches. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiran, Bayad, Daniel J. Toneatti, Benoît Schaller, and Ioanna Kalaitsidou. 2025. "Management Strategies for Isolated Orbital Floor Fractures: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes and Surgical Approaches" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233024

APA StyleMiran, B., Toneatti, D. J., Schaller, B., & Kalaitsidou, I. (2025). Management Strategies for Isolated Orbital Floor Fractures: A Systematic Review of Clinical Outcomes and Surgical Approaches. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233024