Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography for the Evaluation of Pigmented Skin Lesions of the Genital Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

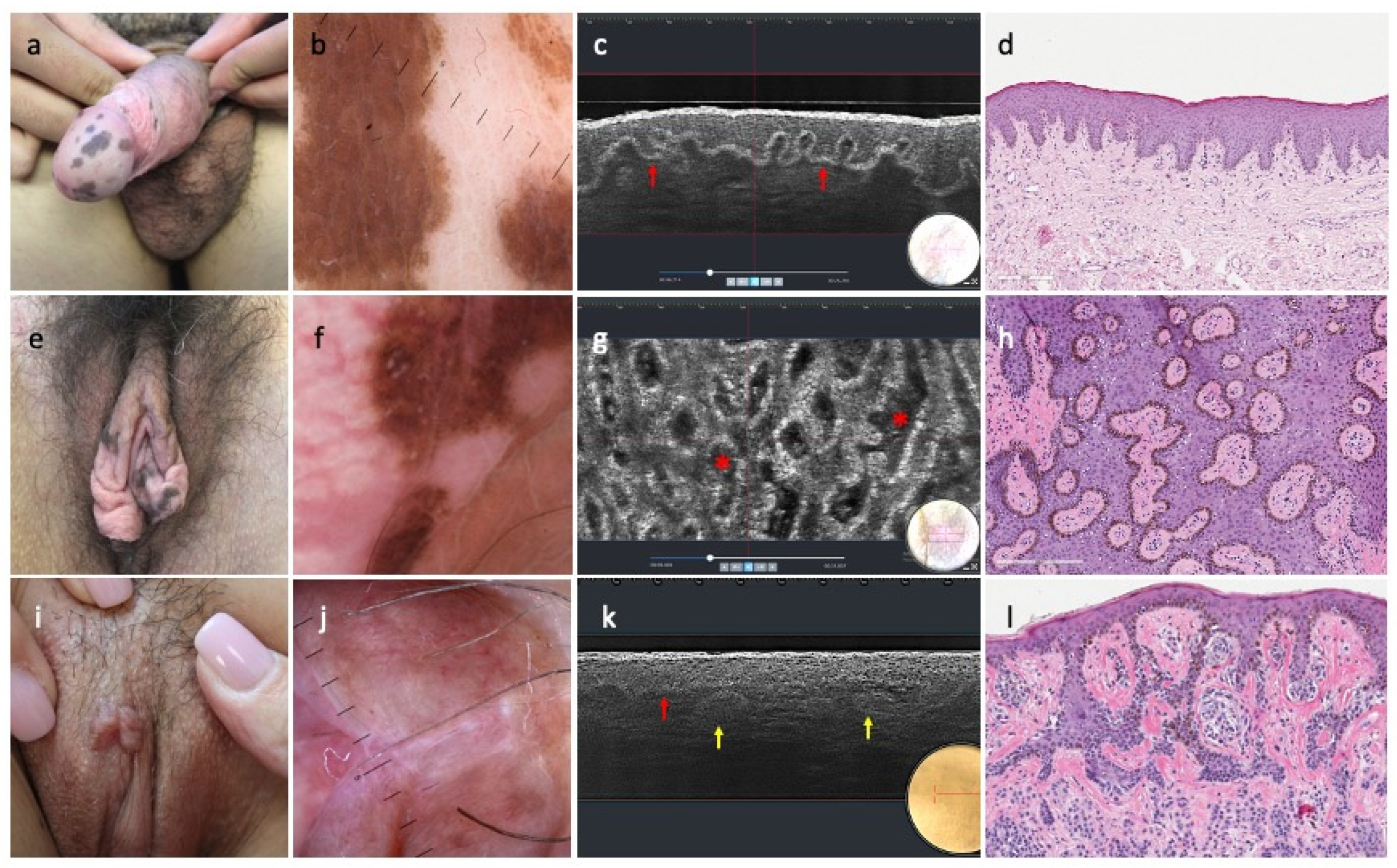

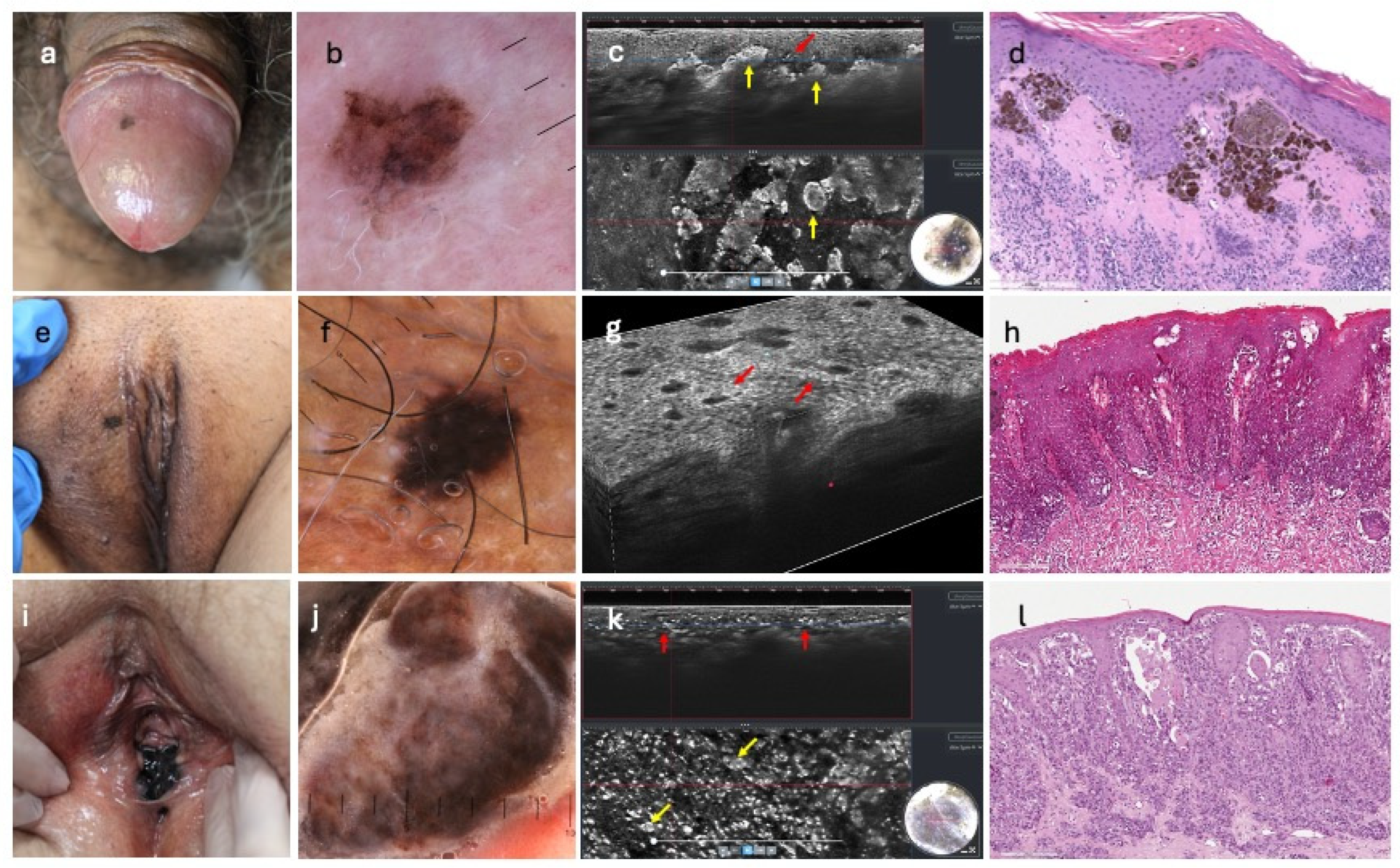

3.1. LC-OCT Vertical Features of Benign PGLs

3.2. LC-OCT Horizontal Mode

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

3.4. Diagnostic Performance of Dermoscopy and LC-OCT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC-OCT | Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography |

References

- Hosler, G.A.; Moresi, J.M.; Barrett, T.L. Nevi with site-related atypia: A review of melanocytic nevi with atypical histologic features based on anatomic site. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2008, 35, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfan, G.; Bıyık Özkaya, D. Genital pigmented lesions. J. Urol. Surg. 2023, 10, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-Ferreira, C.; Ravni, E.; Bourgea, C.; Cinotti, E.; Tognetti, L.; Perrot, J.; Skowron, F. Pigmented genital lesions: A prospective cross-sectional study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e550–e552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, B. Pigmented lesions of the vulva: Vulvar diseases. Dermatol. Clin. 1992, 10, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, M.; Joura, E.; Vieira-Baptista, P.; Van Beurden, M.; Bevilacqua, F.; Bleeker, M.C.G.; Bornstein, J.; Carcopino, X.; Chargari, C.; E Cruickshank, M.; et al. The european society of gynaecological oncology (ESGO), the international society for the study of vulvovaginal disease (ISSVD), the european college for the study of vulval disease (ECSVD) and the european federation for colposcopy (EFC) consensus statements on pre-invasive vulvar lesions. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 830–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronger-Savle, S.; Julien, V.; Duru, G.; Raudrant, D.; Dalle, S.; Thomas, L. Features of pigmented vulval lesions on dermoscopy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 164, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.; Simionescu, O.; Argenziano, G.; Braun, R.; Cabo, H.; Eichhorn, A.; Kirchesch, H.; Malvehy, J.; Marghoob, A.A.; Puig, S.; et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented lesions of the mucosa and the mucocutaneous junction: Results of a multicenter study by the international dermoscopy society (IDS). Arch. Dermatol. 2011, 147, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascalis, A.; Perrot, J.L.; Tognetti, L.; Rubegni, P.; Cinotti, E. Review of dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy features of the mucosal melanoma. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, V.; Cappilli, S.; Di Stefani, A.; Ricci, C.; Perino, F.; Di Nardo, L.; Longo, C.; Peris, K. Confocal assessment of pigmented-mucosal lesions: A monocentric, retrospective evaluation of lip and genital area. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacarrubba, F.; Borghi, A.; Verzì, A.E.; Corazza, M.; Stinco, G.; Micali, G. Dermoscopy of genital diseases: A review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.M.; Lee, K.G.; Choi, W.; Cheong, S.H.; Myung, K.B.; Hahn, H.J. An updated review of mucosal melanoma: Survival meta-analysis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 11, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, K.; Ortner, V.K.; Wenande, E.; Sahu, A.; Paasch, U.; Haedersdal, M. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography in dermato-oncology: A literature review towards harmonized histopathology-integrated terminology. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latriglia, F.; Ogien, J.; Tavernier, C.; Fischman, S.; Suppa, M.; Perrot, J.-L.; Dubois, A. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT) for skin imaging in dermatology. Life 2023, 13, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Levecq, O.; Azimani, H.; Siret, D.; Barut, A.; Suppa, M.; del Marmol, V.; Malvehy, J.; Cinotti, E.; Rubegni, P.; et al. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for high-resolution noninvasive imaging of skin tumors. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogien, J.; Daures, A.; Cazalas, M.; Perrot, J.-L.; Dubois, A. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for three-dimensional skin imaging. Front. Optoelectron. 2020, 13, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Cassalia, F.; Mazza, M.; Del Fiore, P.; Ferrera, N.; Malvehy, J.; Trilli, I.; Rivas, A.C.; Cazzato, G.; Ingravallo, G.; et al. Advancements in Diagnosis of Neoplastic and Inflammatory Skin Diseases: Old and Emerging Approaches. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deußing, M.; Schuh, S.; Thamm, J.; Winkler, D.; Schneider, S.; Nau, T.; Darsow, U.; Schnabel, V.; Ulrich, M.; Nguyen, L.; et al. S1 guideline for imaging diagnostics for skin diseases. J. Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, S.; Kuo, Y.; Pathak, G.; Agarwal, P.; Horgan, A.; Parikh, P.; Deshmukh, F.; Rao, B.K. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography for the diagnosis of skin tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Zeinaty, P.; Suppa, M.; Del Marmol, V.; Tavernier, C.; Dauendorffer, J.; Lebbé, C.; Baroudjian, B. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC-OCT): A novel tool of cutaneous imaging for non-invasive diagnosis of pigmented lesions of genital area. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, e1081–e1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowowiejska, J.; Ordon, A.J.; Purpurowicz, P.; Argenziano, G.; Piccolo, V. Many faces of melanoma: A comparison between cutaneous, mucosal, acral, nail, and ocular malignancy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2025, 38, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Amaral, T.; Peris, K.; Hauschild, A.; Arenberger, P.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Bastholt, L.; Bataille, V.; Brochez, L.; del Marmol, V.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment—Update. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 215, 115153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.G.; Bagwan, I.; Board, R.E.; Capper, S.; Coupland, S.E.; Glen, J.; Lalondrelle, S.; Mayberry, A.; Muneer, A.; Nugent, K.; et al. Ano-uro-genital mucosal melanoma UK national guidelines. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 135, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giorgi, V.; Gori, A.; Salvati, L.; Scarfì, F.; Maida, P.; Trane, L.; Silvestri, F.; Portelli, F.; Venturi, F.; Covarelli, P.; et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. Arch. Dermatol. 2020, 156, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palla, M.; Ferrara, G.; Caracò, C.; Scarfì, F.; Maida, P.; Trane, L.; Silvestri, F.; Portelli, F.; Venturi, F.; Covarelli, P.; et al. Where reflectance confocal microscopy provides the greatest benefit for diagnosing skin cancers: The experience of the national cancer institute of naples. Cancers 2025, 17, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, A.; Star, P.; Guitera, P. Advances in the use of reflectance confocal microscopy in melanoma. Melanoma Manag. 2018, 5, MMT04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Valdés, S.; Bustos, S.; Donoso, F.; Caussade, M.-C.; Antunez-Lay, A.; Droppelmann, K.; Uribe, P.; Pellacani, G.; Abarzúa-Araya, A.; Navarrete-Dechent, C. Reflectance confocal microscopy reduces biopsies in adults and children: A prospective real-life study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscarella, E.; Ronchi, A.; Scharf, C.; Briatico, G.; Tancredi, V.; Longo, C.; Balato, A.; Argenziano, G. Limits of reflectance confocal microscopy in melanoma diagnosis. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deußing, M. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography in melanocytic tumors. Dermatologie 2025, 76, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soglia, S.; Pérez-Anker, J.; Albero, R.; Alós, L.; Berot, V.; Castillo, P.; Cinotti, E.; Del Marmol, V.; Fakih, A.; García, A.; et al. Understanding the anatomy of dermoscopy of melanocytic skin tumours: Correlation in vivo with line-field optical coherence tomography. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Anker, J.; Soglia, S.; Lenoir, C.; Albero, R.; Alos, L.; García, A.; Alejo, B.; Cinotti, E.; Cano, C.O.; Habougit, C.; et al. Criteria for melanocytic lesions in LC-OCT. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 2005–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Anker, J.; Puig, S.; Alos, L.; Albero, R.; Alos, L.; García, A.; Alejo, B.; Cinotti, E.; Cano, C.O.; Habougit, C.; et al. Morphological evaluation of melanocytic lesions with three-dimensional line-field confocal optical coherence tomography: Correlation with histopathology and reflectance confocal microscopy. A pilot study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2222–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, S.; Ruini, C.; Perwein, M.K.E.; Daxenberger, F.; Gust, C.; Sattler, E.C.; Welzel, J. Line-field confocal optical coherence tomography: A new tool for the differentiation between nevi and melanomas? Cancers 2022, 14, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Anker, J.; Soglia, S.; Puig, S.; García, A.; Albero, R.; Alejo, B.; Cinotti, E.; Cano, C.O.; Habougit, C.; Skowron, F.; et al. Melanocytic clefting is associated with melanoma on LC-OCT. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribe, A. Melanocytic lesions of the genital area with attention given to atypical genital nevi. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2008, 35, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, A.M.; Merkel, E.A.; Zhang, B.; Bubley, J.A.; Verzì, A.E.; Lee, C.Y.; Gerami, P. A clinical, histologic, and follow-up study of genital melanosis in men and women. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuestas, D.; Perafan, A.; Forero, Y.; Bonilla, J.; Velandia, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Motta, A.; Herrera, H.; Rolon, M. Angiokeratomas, not everything is fabry disease. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, F.L.; ten Eikelder, M.L.G.; van Geloven, N.; Kapiteijn, E.H.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Hughes, G.; Nooij, L.S.; Jozwiak, M.; Tjiong, M.Y.; de Hullu, J.M.; et al. Evaluation of treatment, prognostic factors, and survival in 198 vulvar melanoma patients: Implications for clinical practice. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tot. | Melanoses | Nevi | Melanomas | Angiokeratomas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 88 | n = 56 | n = 21 | n = 10 | n = 9 | |

| F | 65 (74%) | 37 (66%) | 14 (67%) | 10 (100%) | 2 (22%) |

| M | 23 (26%) | 19 (34%) | 7 (33%) | - | 7 (78%) |

| Labia majora | 17/37 (46%) | 5/14 (36%) | - | - | |

| Labia minora | 8/37 (21%) | 4/14 (29%) | 5/10 (50%) | - | |

| Clitoris | 1/37 (3%) | 2/14 (14%) | - | - | |

| Pubis | 7/37 (19%) | 1/14 (7%) | 5/10 (50%) | 2/9 (22%) | |

| Perianal | 4/37 (11%) | 2/14 (14%) | - | - | |

| Glans penis | 3/19 (16%) | 2/7 (29%) | - | - | |

| Prepuce | 3/19 (16%) | 1/7 (14%) | - | - | |

| Penis | 9/19 (47%) | 3/7 (43%) | - | 1/9 (11%) | |

| Pubis | - | - | - | - | |

| Scrotum | 4/19 (21%) | 1/7 (14%) | - | 6/9 (67%) | |

| Melanoses | Nevi | Angiokeratomas | Melanomas | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 56 | n = 21 | n = 9 | n = 10 | ||

| Epidermis | |||||

| Regular epidermis | 43 (77) | 16 (76) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Irregular epidermis (broadening, dyskeratosis) | 10 (18) | 5 (24) | 7 (78) | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| Pagetoid spread | 3 (5) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| Atypical nests | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | <0.001 |

| CEJ and Upper/Mid-Dermis | |||||

| Flat | 9 (16) | 3 (14) | 9 (100) | 5 (50) | <0.001 |

| Undulated | 47 (84) | 18 (86) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | <0.001 |

| Continuous | 56 (100) | 21 (100) | 9 (100) | 7 (70) | <0.001 |

| Atypical cells at DEJ | 12 (21) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| Melanocytic Nests at CEJ and Papillary Dermis | |||||

| Dense | 0 (0) | 14 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Dense and sparse | 0 (0) | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| Discohesive | 0 (0) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 3 (30) | <0.001 |

| Circular/Ovoidal Dark Spaces | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Plump Bright Cells | 14 (25) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 0.08 |

| Melanoses | Nevi | Angiokeratomas | Melanomas | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 56 | n = 21 | n = 9 | n = 10 | ||

| Epidermis | |||||

| Honeycomb pattern | 43 (77) | 16 (76) | 9 (100) | 5 (50) | 0.09 |

| Cobblestone pattern | 10 (18) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 0.05 |

| Disarray (broadening and atypical keratinocytes) | 3 (5) | 4 (19) | 7 (78) | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| Pagetoid spread of atypical cells | 3 (5) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| CEJ and Upper/Mid-Dermis | |||||

| Ringed pattern | 36 (64) | 13 (62) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | 0.003 |

| Draped pattern | 14 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| Meshwork pattern | 4 (7) | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 0.001 |

| Clod pattern | 0 (0) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Nonspecific pattern | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0.46 |

| Papillae | |||||

| Edged | 37(66) | 7(33) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | 0.74 |

| Non-edged | 17(30) | 2(10) | 0 (0) | 6 (60) | 0.02 |

| Mixed | 2(4) | 2(10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Distribution of Papillae | |||||

| Homogeneous | 44(79) | 9(43) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| Nonhomogenous | 12(21) | 2(10) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| Melanocytic Nests at CEJ and Papillary Dermis | |||||

| Dense | 0 (0) | 14 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Dense and sparse | 0 (0) | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| Discohesive | 0 (0) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 3 (30) | <0.001 |

| Circular/Ovoidal Dark Spaces | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Plump Bright Cells | 14 (25) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 0.10 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Accuracy (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoses | LC-OCT | 89.4 (78.5–95.0) | 100 (91.2–100.0) | 93.8 |

| Dermoscopy | 83.9 (72.2–91.3) | 100 (91.2–100.0) | 90.6 | |

| AGN | LC-OCT | 50.0 (18.9–73.3) | 100 (95.8–100.0) | 96.9 |

| Dermoscopy | 16.7 (6.3–54.7) | 95.6 (88.8–98.2) | 90.6 | |

| Common Nevi | LC-OCT | 100 (84.5–100.0) | 100 (95.1–100.0) | 100 |

| Dermoscopy | 86.7 (65.4–95.0) | 100 (95.1–100.0) | 97.9 | |

| Angiokeratomas | LC-OCT | 100 (70.1–100.0) | 100 (95.8–100.0) | 100 |

| Dermoscopy | 88.9 (56.5–98.0) | 100 (95.8–100.0) | 98.9 | |

| Melanomas | LC-OCT | 100 (72.2–100.0) | 89.5 (81.3–94.4) | 90.6 |

| Dermoscopy | 70.0 (39.7–89.2) | 82.6 (73.2–89.1) | 81.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cappilli, S.; Palmisano, G.; Cinotti, E.; Boussingault, L.; Pellegrino, L.; Tognetti, L.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Pérez-Anker, J.; Perrot, J.-L.; Santoro, A.; et al. Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography for the Evaluation of Pigmented Skin Lesions of the Genital Area. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233023

Cappilli S, Palmisano G, Cinotti E, Boussingault L, Pellegrino L, Tognetti L, Fragomeni SM, Pérez-Anker J, Perrot J-L, Santoro A, et al. Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography for the Evaluation of Pigmented Skin Lesions of the Genital Area. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233023

Chicago/Turabian StyleCappilli, Simone, Gerardo Palmisano, Elisa Cinotti, Lucas Boussingault, Luca Pellegrino, Linda Tognetti, Simona Maria Fragomeni, Javiera Pérez-Anker, Jean-Luc Perrot, Angela Santoro, and et al. 2025. "Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography for the Evaluation of Pigmented Skin Lesions of the Genital Area" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233023

APA StyleCappilli, S., Palmisano, G., Cinotti, E., Boussingault, L., Pellegrino, L., Tognetti, L., Fragomeni, S. M., Pérez-Anker, J., Perrot, J.-L., Santoro, A., Garganese, G., Zannoni, G. F., Suppa, M., Peris, K., & Di Stefani, A. (2025). Line-Field Confocal Optical Coherence Tomography for the Evaluation of Pigmented Skin Lesions of the Genital Area. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233023