Ocular Surface Parameters in Glaucoma Patients Treated with Topical Prostaglandin Analogs and the Importance of Switching to Preservative-Free Eye Drops—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

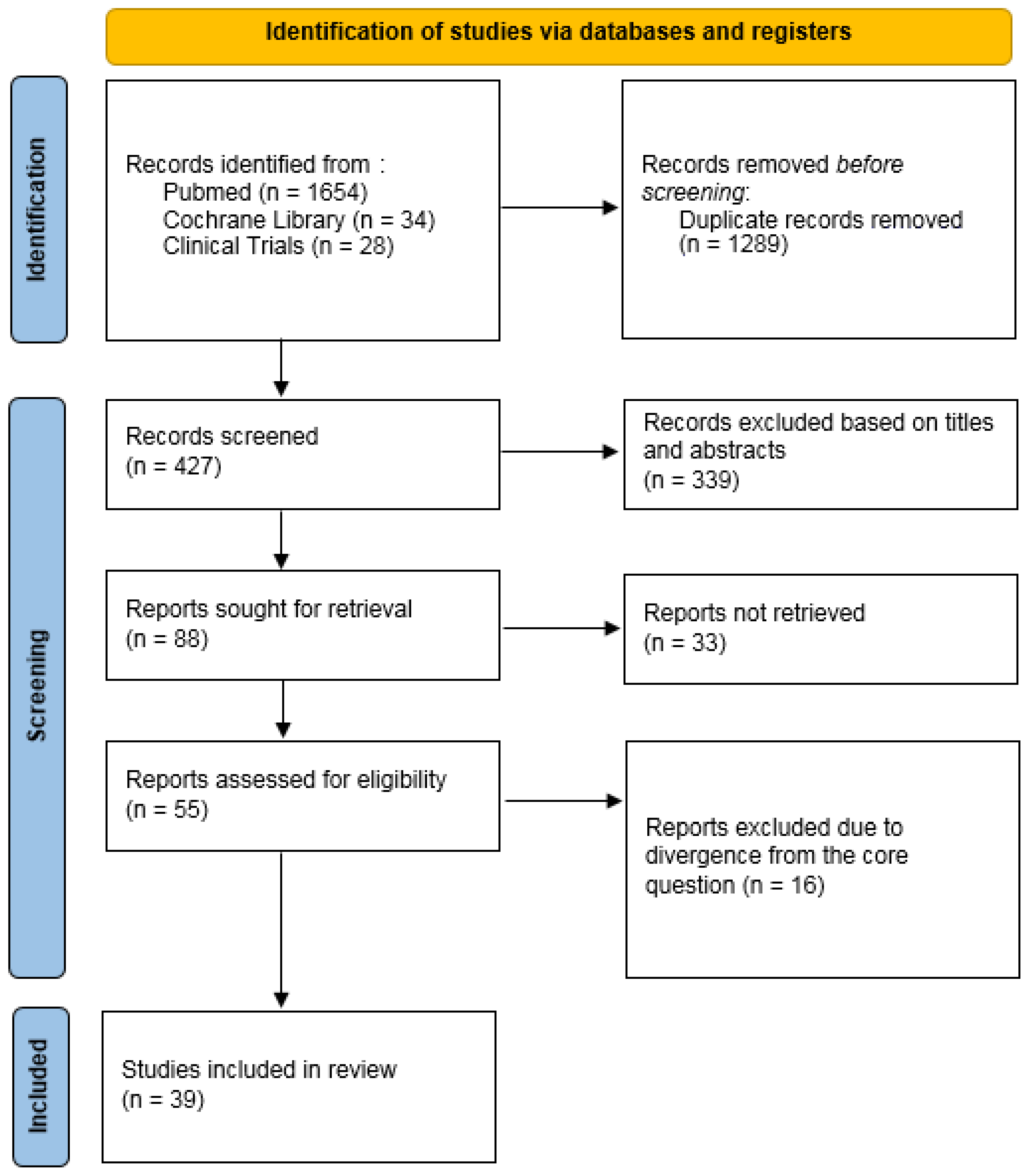

2. Materials and Methods

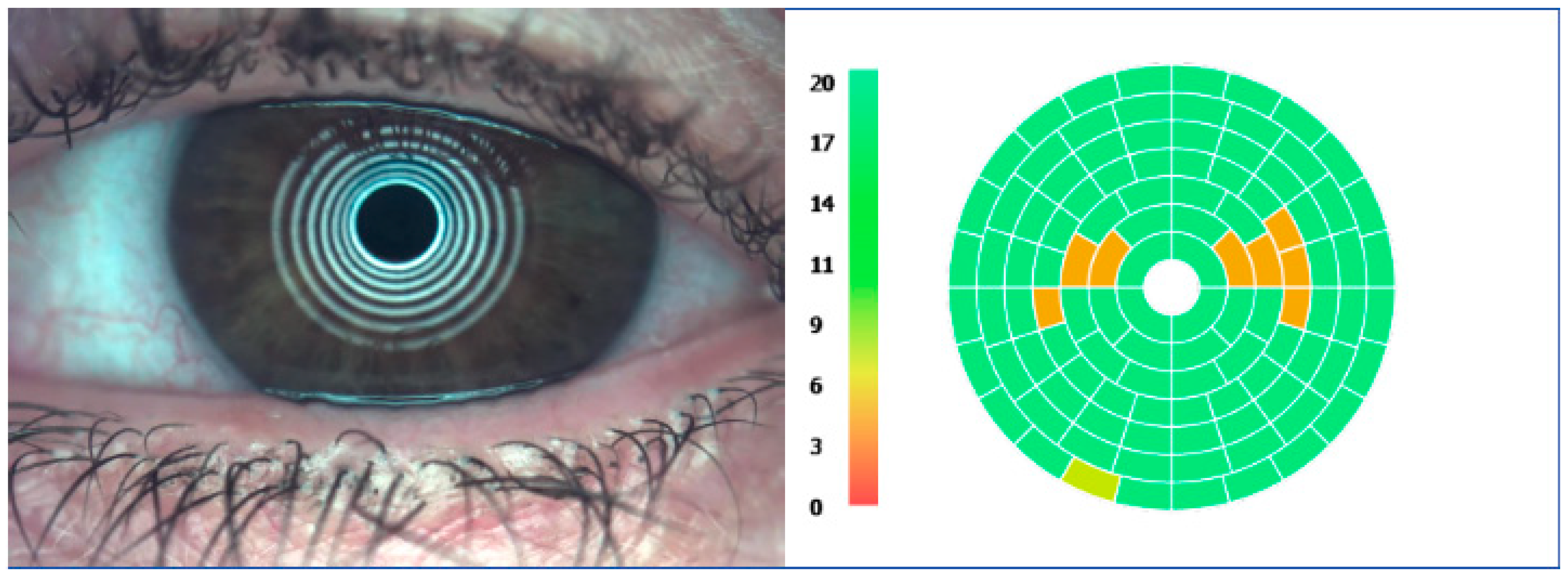

- Population—glaucoma patients;

- Intervention—pharmacotherapy with PGA eye drops;

- Comparison—correlation of ocular surface symptoms with specific substances included in eye drop formulations;

- Outcomes—quantification of adverse effects through specific diagnostic methods.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Phosphates

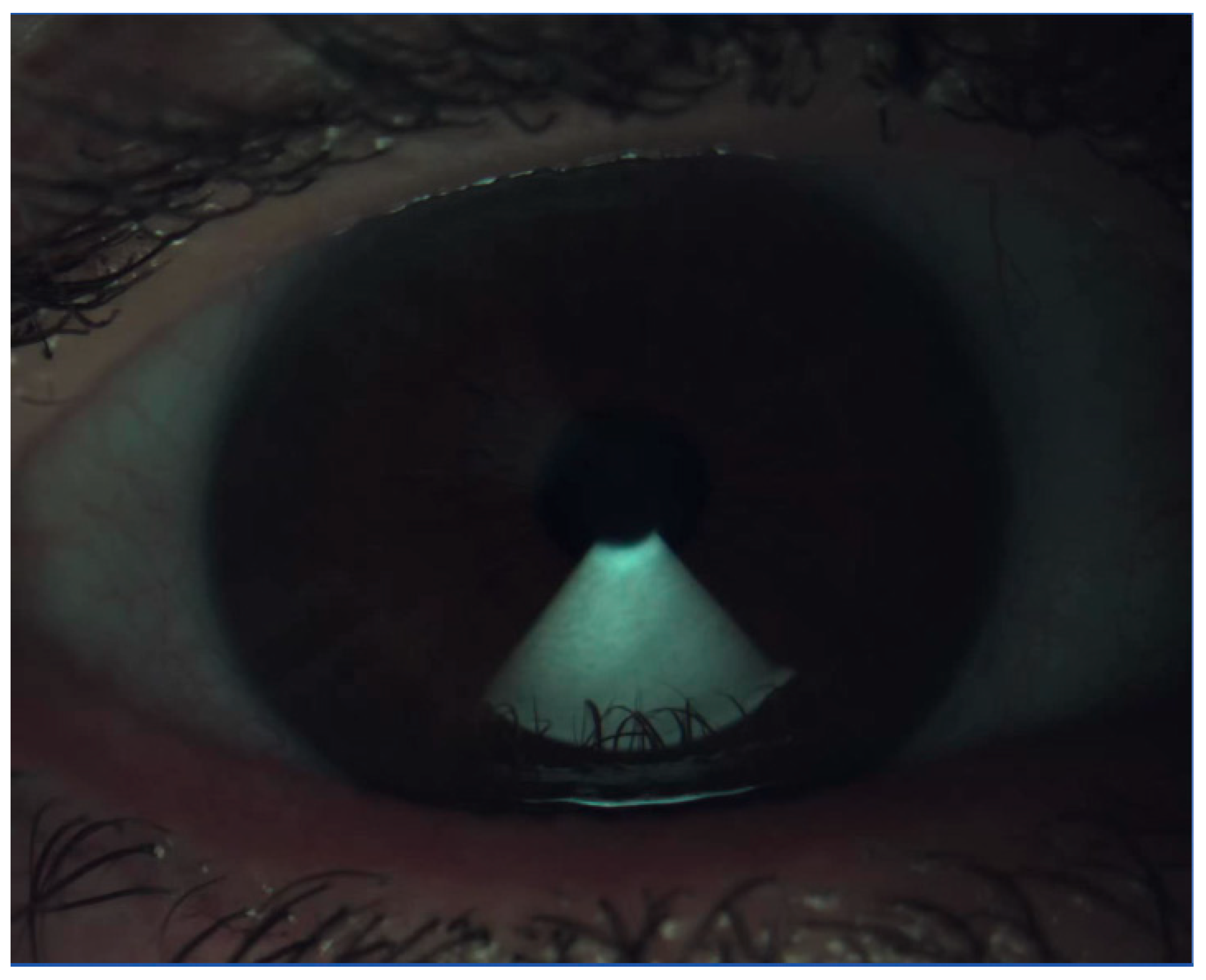

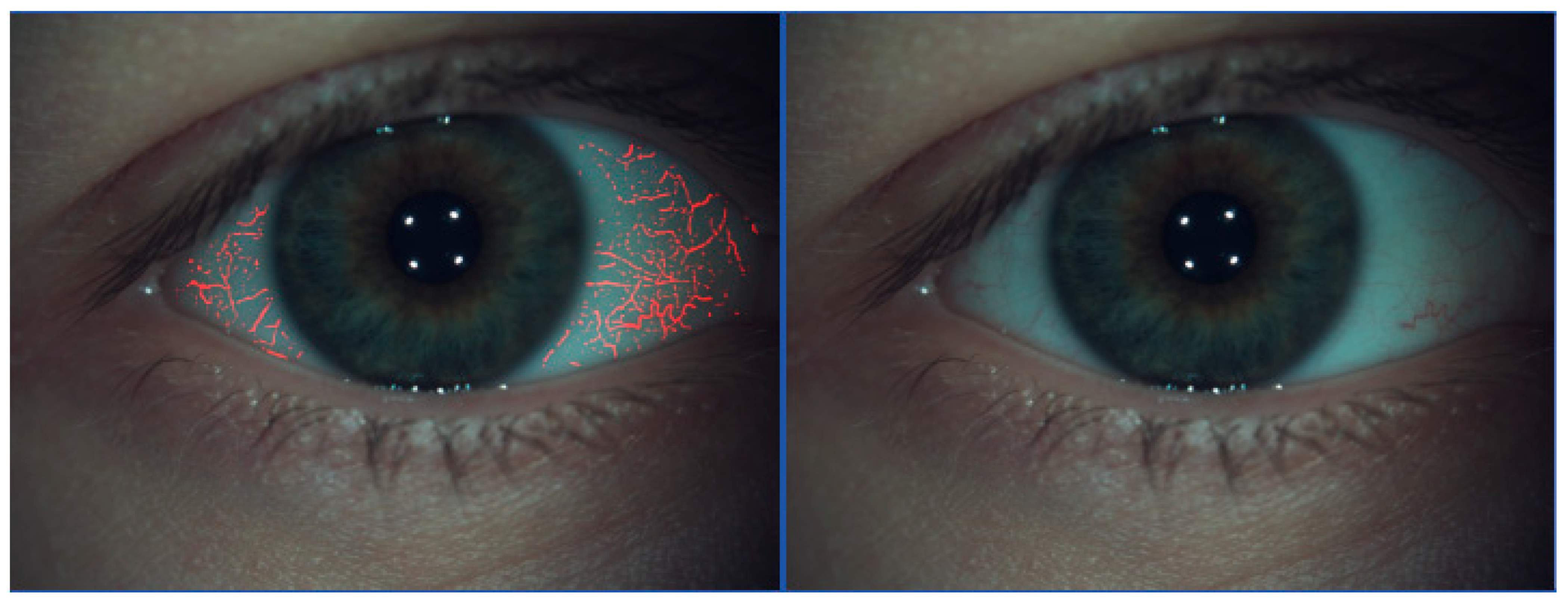

4.2. Slit-Lamp Assessment

4.3. Quantification of OSD with Scales

4.4. Tear Film Osmolarity

4.5. Other OSD Evaluation Modalities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DED | Dry Eye Disease |

| OSD | Ocular Surface Disease |

| OSDI | Ocular Surface Disease Index |

| PF | Preservative-Free |

| NITBUT | Non-invasive Tear Break-up Time |

| LIPCOF | Lid-Parallel Conjunctival Fold |

| RCT | Randomized Clinical Trial |

References

- Tan, Z.; Tung, T.-H.; Xu, S.-Q.; Chen, P.-E.; Chien, C.-W.; Jiang, B. Personality types of patients with glaucoma: A systematic review of observational studies. Medicine 2021, 100, e25914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cordeiro, M.F.; Gandolfi, S.; Gugleta, K.; Normando, E.M.; Oddone, F. How latanoprost changed glaucoma management. Acta Ophthalmol. 2023, 102, e140–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Deng, R.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of travoprost and latanoprost for the management of open-angle glaucoma given as an evening dose. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noecker, R.S.; Dirks, M.S.; Choplin, N.; Bimatoprost/Latanoprost Study Group. Comparison of latanoprost, bimatoprost, and travoprost in patients with elevated intraocular pressure: A 12-week, randomized, masked-evaluator multicenter study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 137, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uusitalo, H.; E Pillunat, L.; Ropo, A.; Phase III Study Investigators. Efficacy and safety of tafluprost 0.0015% versus latanoprost 0.005% eye drops in open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension: 24-month results of a randomized, double-masked phase III study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010, 88, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstas, A.-G.; Boboridis, K.G.; Kapis, P.; Marinopoulos, K.; Voudouragkaki, I.C.; Panayiotou, D.; Mikropoulos, D.G.; Pagkalidou, E.; Haidich, A.-B.; Katsanos, A.; et al. 24-Hour Efficacy and Ocular Surface Health with Preservative-Free Tafluprost Alone and in Conjunction with Preservative-Free Dorzolamide/Timolol Fixed Combination in Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients Insufficiently Controlled with Preserved Latanoprost Monotherapy. Adv. Ther. 2016, 34, 221–235, Erratum in Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 2572–2573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01316-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dams, I.; Wasyluk, J.; Prost, M.; Kutner, A. Therapeutic uses of prostaglandin F(2α) analogues in ocular disease and novel synthetic strategies. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2013, 104–105, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alm, A.; Grierson, I.; Shields, M.B. Side effects associated with prostaglandin analog therapy. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2008, 53 (Suppl. S1), S93–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechtner, R.D.; Godfrey, D.G.; Budenz, D.; A Stewart, J.; Stewart, W.C.; Jasek, M.C. Prevalence of ocular surface complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea 2010, 29, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucukevcilioglu, M.; Bayer, A.; Uysal, Y.; I Altinsoy, H. Prostaglandin associated periorbitopathy in patients using bimatoprost, latanoprost and travoprost. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2013, 42, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Bicket, A.K.; Marwah, S.; Stein, J.D.; Kishor, K.S.; SOURCE Consortium. Incidence of Acute Cystoid Macular Edema after Starting a Prostaglandin Analog Compared with Other Classes of Glaucoma Medications. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2024, 8, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patchinsky, A.; Petitpain, N.; Gillet, P.; Angioi-Duprez, K.; Schmutz, J.L.; Bursztejn, A.C. Dermatological adverse effects of anti-glaucoma eye drops: A review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.; Lee, B.S.; Periman, L.M. Dry eye disease: Identification and therapeutic strategies for primary care clinicians and clinical specialists. Ann. Med. 2022, 55, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stapleton, F.; Velez, F.G.; Lau, C.; Wolffsohn, J.S. Dry eye disease in the young: A narrative review. Ocul. Surf. 2023, 31, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeti, S.; Kheirkhah, A.; Yin, J.; Dana, R. Management of meibomian gland dysfunction: A review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 65, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baudouin, C.; Labbé, A.; Liang, H.; Pauly, A.; Brignole-Baudouin, F. Preservatives in eyedrops: The good, the bad and the ugly. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010, 29, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, D.W.; Alaghband, P.; Lim, K.S. Preservatives in glaucoma medication. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tu, E.Y. Balancing antimicrobial efficacy and toxicity of currently available topical ophthalmic preservatives. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 28, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Public Statement on the Use of Phosphate Buffers in Eye Drops; European Medicines Agency (EMA): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kahook, M.Y.; Rapuano, C.J.; Messmer, E.M.; Radcliffe, N.M.; Galor, A.; Baudouin, C. Preservatives and ocular surface disease: A review. Ocul. Surf. 2024, 34, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonniard, A.A.; Yeung, J.Y.; Chan, C.C.; Birt, C.M. Ocular surface toxicity from glaucoma topical medications and associated preservatives such as benzalkonium chloride (BAK). Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2016, 12, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedengran, A.; Kolko, M. The molecular aspect of anti-glaucomatous eye drops—Are we harming our patients? Mol. Asp. Med. 2023, 93, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouzeau, C.; Godefroy, D. Hyperosmolarity potentiates toxic effects of benzalkonium chloride on conjunctival epithelial cells in vitro. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Özalp, O.; Atalay, E.; Alataş, İ.Ö.; Küskü Kiraz, Z.; Yıldırım, N. Assessment of Phosphate and Osmolarity Levels in Chronically Administered Eye Drops. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 49, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jhanji, V.; Rapuano, C.J.; Vajpayee, R.B. Corneal calcific band keratopathy. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 22, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Questions and Answers on the Use of Phosphates in Eye Drops; EMA/CHMP/753373/2012; Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brott, N.R.; Zeppieri, M.; Ronquillo, Y. Schirmer Test. 2024 Feb 24. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani-Mojarrad, N.; Vianya-Estopa, M.; Martin, E.; Sweeney, L.E.; Terry, L.; Huntjens, B.; Wolffsohn, J.S.; BUCCLE Research Group. Optimizing the methodology for the assessment of bulbar conjunctival lissamine green staining. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2024, 101, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, D.O.; Ferrandez, B.; Mateo, A.; Polo, V.; Garcia-Martin, E. Meibomian Gland Changes in Open-angle Glaucoma Users Treated with Topical Medication. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2021, 98, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magno, M.; Moschowits, E.; Arita, R.; Vehof, J.; Utheim, T.P. Intraductal meibomian gland probing and its efficacy in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2021, 66, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, I.J.; Park, M.C.; Lim, H.; Lee, S.H. Aesthetic blepharoptosis correction with release of fibrous web bands between the levator aponeurosis and orbital fat. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2012, 23, e52–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, V.; Gaeta, A.; Barone, G.; Confalonieri, F.; Tredici, C.; Vinciguerra, P.; Di Maria, A. Proposing a New Classification for Managing Prostaglandin-Induced Enophthalmos in Glaucoma Patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Narang, R.; Agarwal, A. Refractive cataract surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2024, 35, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Benítez-Del-Castillo, J.M.; Loya-Garcia, D.; Inomata, T.; Iyer, G.; Liang, L.; Pult, H.; Sabater, A.L.; Starr, C.E.; Vehof, J.; et al. TFOS DEWS III: Diagnostic Methodology. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 279, 387–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Wen, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Fan, Z.; Liang, X.; Liang, L. Quantitative evaluation of lipid layer thickness and blinking in children with allergic conjunctivitis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 259, 2795–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ballesteros-Sánchez, A.; Sánchez-González, J.-M.; Borrone, M.A.; Borroni, D.; Rocha-De-Lossada, C. The Influence of Lid-Parallel Conjunctival Folds and Conjunctivochalasis on Dry Eye Symptoms with and Without Contact Lens Wear: A Review of the Literature. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2024, 13, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Altay, Y. Which factor have more adverse effect on ocular surface of patients treated with antiglaucoma drops; drug type, number of drugs or drug intensity? Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2025, 44, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashbayev, B.; Utheim, T.P.; Utheim, Ø.A.; Ræder, S.; Jensen, J.L.; Yazdani, M.; Lagali, N.; Vitelli, V.; Dartt, D.A.; Chen, X. Utility of Tear Osmolarity Measurement in Diagnosis of Dry Eye Disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pena-Verdeal, H.; Garcia-Resua, C.; Garcia-Queiruga, J.; Sabucedo-Villamarin, B.; Yebra-Pimentel, E.; Giraldez, M.J. Diurnal variations of tear film osmolarity on the ocular surface. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2022, 106, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bron, A.J.; Willshire, C. Tear Osmolarity in the Diagnosis of Systemic Dehydration and Dry Eye Disease. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abusharha, A.; Alsaqar, A.; Fagehi, R.; Alobaid, M.; Almayouf, A.; Alajlan, S.; Omaer, M.; Alahmad, E.; Masmali, A. Evaluation of Tear Film Osmolarity Among Diabetic Patients Using a TearLab Osmometer. Clin. Optom. 2021, 13, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Surico, P.L.; Saricay, L.Y.; Singh, R.B.; Kahale, F.; Romano, F.M.; Dana, R.M. Corneal Sensitivity and Neuropathy in Patients With Ocular Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Cornea 2024, 44, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree, J.R.; Tannir, S.; Tran, K.; Boente, C.S.; Ali, A.; Borschel, G.H. Corneal Nerve Assessment by Aesthesiometry: History, Advancements, and Future Directions. Vision 2024, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abusharha, A.A.B.; Pearce, E.I. The effect of low humidity on the human tear film. Cornea 2013, 32, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.-S.; Lee, Y.; Paik, H.J.; Kim, D.H. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Influence of Temperature and Humidity on Dry Eye Disease. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 37, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, W.; Woo, I.H.; Eom, Y.; Song, J.S. Short-term changes in tear osmolarity after instillation of different osmolarity eye drops in patients with dry eye. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Konstas, A.-G.; Boboridis, K.G.; Athanasopoulos, G.P.; Haidich, A.-B.; Voudouragkaki, I.C.; Pagkalidou, E.; Katsanos, A.; Katz, L.J. Changing from preserved, to preservative-free cyclosporine 0.1% enhanced triple glaucoma therapy: Impact on ocular surface disease-a randomized controlled trial. Eye 2023, 37, 3666–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gulias-Cañizo, R.; Rodríguez-Malagón, M.E.; Botello-González, L.; Belden-Reyes, V.; Amparo, F.; Garza-Leon, M. Applications of Infrared Thermography in Ophthalmology. Life 2023, 13, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, C.; Huang, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, B.; Zhuang, S.; Cao, G.; Hu, Y.; Gu, Z. Comparing the corneal temperature of dry eyes with that of normal eyes via high-resolution infrared thermography. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1526165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, H.; Huang, L.; Fang, X.; Xie, Z.; Xiao, X.; Luo, S.; Lin, Y.; Wu, H. The photothermal effect of intense pulsed light and LipiFlow in eyelid related ocular surface diseases: Meibomian gland dysfunction, Demodex and blepharitis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chung, H.S.; Rhim, J.W.; Park, J.H. Combination treatment with intense pulsed light, thermal pulsation (LipiFlow), and meibomian gland expression for refractory meibomian gland dysfunction. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 3311–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, H.; Stapleton, F.; Downie, L.E.; Chidi-Egboka, N.C.; Mingo-Botin, D.; Arnalich-Montiel, F.; Rauz, S.; Recchioni, A.; Sitaula, S.; Markoulli, M.; et al. The impact of dry eye disease on patient-reported quality of life: A Save Sight Dry Eye Registry study. Ocul. Surf. 2025, 37, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Substance Name | Type | Purpose in Formulation | Potential Adverse Effects | Treatment Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzalkonium chloride (BAK) | Preservative | Antimicrobial—dissolves cell walls and membranes |

|

|

| Cetrimonium bromide | Preservative | Antimicrobial detergent |

| |

| Polyquad® (Polyquaternium-1) | Preservative | Antimicrobial—acts on cell membranes |

| |

| Purite® (Stabilized oxychloro complex of chlorite, chlorate andchlorine dioxide) | Oxidative | Oxidation of intracellular lipids and glutathione |

| |

| SofZia® (Borate, sorbitol, propylene glycol and zinc) | Ion-buffered preservative | Maintains sterility |

| |

| Phosphate buffers | Excipient (buffer system) | pH regulation, solubility enhancement |

| |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Chelator, stabilizer | Enhances preservative efficacy |

| |

| Propylparaben | Preservative | Antimicrobial agent |

| |

| Chlorobutanol | Preservative | Antimicrobial agent |

| |

| Sodium perborate | Oxidative | Hydrolyzed into hydrogen peroxide and borate |

| |

| Octoxynol 40 | Stabilizer | Antimicrobial—cell lysis and membrane permeabilization |

| |

| Chlorhexidine | Antiseptic | Bacteriostatic |

| |

| Glycerol, Hyaluronic acid, PEG/PPG | Humectants, excipients | Moisturizing, improve drop viscosity and comfort |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wasyluk, J.; Rotuski, G.; Dubisz, M.; Różycki, R. Ocular Surface Parameters in Glaucoma Patients Treated with Topical Prostaglandin Analogs and the Importance of Switching to Preservative-Free Eye Drops—A Systematic Review. Life 2025, 15, 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121837

Wasyluk J, Rotuski G, Dubisz M, Różycki R. Ocular Surface Parameters in Glaucoma Patients Treated with Topical Prostaglandin Analogs and the Importance of Switching to Preservative-Free Eye Drops—A Systematic Review. Life. 2025; 15(12):1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121837

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasyluk, Jaromir, Grzegorz Rotuski, Marta Dubisz, and Radosław Różycki. 2025. "Ocular Surface Parameters in Glaucoma Patients Treated with Topical Prostaglandin Analogs and the Importance of Switching to Preservative-Free Eye Drops—A Systematic Review" Life 15, no. 12: 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121837

APA StyleWasyluk, J., Rotuski, G., Dubisz, M., & Różycki, R. (2025). Ocular Surface Parameters in Glaucoma Patients Treated with Topical Prostaglandin Analogs and the Importance of Switching to Preservative-Free Eye Drops—A Systematic Review. Life, 15(12), 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121837