Dopaminergic Genetic Variation and Trait Impulsivity: The Role of COMT rs4680 in Mixed Behavioral and Substance Addictions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Measures

2.3. Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Translational Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Luan, S.; Wu, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, W.; Hertwig, R. Impulsivity is a stable, measurable, and predictive psychological trait. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2321758121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Roige, S.; Jennings, M.V.; Thorpe, H.H.A.; Mallari, J.E.; van der Werf, L.C.; Bianchi, S.B.; Huang, Y.; Lee, C.; Mallard, T.T.; Barnes, S.A.; et al. CADM2 is implicated in impulsive personality and numerous other traits by genome- and phenome-wide association studies in humans and mice. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.R.; Potenza, M.N. Addictions and Personality Traits: Impulsivity and Related Constructs. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2014, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y.H.C.; Potenza, M.N. Gambling Disorder and Other Behavioral Addictions: Recognition and Treatment. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnet, J. Neurobiological underpinnings of reward anticipation and outcome evaluation in gambling disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economidou, D.; Theobald, D.; Robbins, T.; Everitt, B.J.; Dalley, J.W. Norepinephrine and Dopamine Modulate Impulsivity on the Five-Choice Serial Reaction Time Task Through Opponent Actions in the Shell and Core Sub-Regions of the Nucleus Accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.J.; Waterhouse, B.D.; Gao, W.-J. New perspectives on catecholaminergic regulation of executive circuits: Evidence for independent modulation of prefrontal functions by midbrain dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanis, N.C.; van Os, J.; Avramopoulos, D.; Smyrnis, N.; Evdokimidis, I.; Stefanis, C.N. Effect of COMT Val158Met Polymorphism on the Continuous Performance Test, Identical Pairs Version: Tuning Rather Than Improving Performance. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1752–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumontheil, I.; Roggeman, C.; Ziermans, T.; Peyrard-Janvid, M.; Matsson, H.; Kere, J.; Klingberg, T. Influence of the COMT genotype on working memory and brain activity changes during development. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, N.P.; Robbins, T.W. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresco, S.B. Prefrontal dopamine and behavioral flexibility: Shifting from an “inverted-U” toward a family of functions. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilder, R.; Volavka, J.; Lachman, H.; Grace, A.A. The Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Polymorphism: Relations to the Tonic–Phasic Dopamine Hypothesis and Neuropsychiatric Phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1943–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabant, E.M.; Hariri, A.R.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Munoz, K.E.; Mattay, V.S.; Kolachana, B.S.; Egan, M.F.; Weinberger, D.R. Catechol O-methyltransferase Val158Met Genotype and Neural Mechanisms Related to Affective Arousal and Regulation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Xue, G.; Chen, C.; Lu, Z.-L.; Chen, C.; Lei, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, B.; Moyzis, R.K.; et al. COMT Val158Met polymorphism interacts with stressful life events and parental warmth to influence decision making. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscutti, A.; Pigoni, A.; Delvecchio, G.; Lazzaretti, M.; Mandolini, G.M.; Girardi, P.; Ferro, A.; Sala, M.; Abbiati, V.; Cappucciati, M.; et al. The Influence of 5-HTTLPR, BDNF Rs6265 and COMT Rs4680 Polymorphisms on Impulsivity in Bipolar Disorder: The Role of Gender. Genes 2022, 13, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeiro-De-Souza, M.G.; Stanford, M.S.; Bio, D.S.; Machado-Vieira, R.; Moreno, R.A. Association of the COMT Met158 allele with trait impulsivity in healthy young adults. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013, 7, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, C.B.; Hansen, A.; Hughes, R.L.; McNerney, M.W. Dimensions of Craving Interact with COMT Genotype to Predict Relapse in Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder Six Months after Treatment. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.J.; Tunbridge, E.M. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): A gene contributing to sex differences in brain function, and to sexual dimorphism in the predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 3037–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Xie, T.; Ramsden, D.B.; Ho, S.L. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase down-regulation by estradiol. Neuropharmacology 2003, 45, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacht, J.P. COMT val158met moderation of dopaminergic drug effects on cognitive function: A critical review. Pharmacogenom. J. 2016, 16, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recław, R.; Chmielowiec, K.; Suchanecka, A.; Boroń, A.; Chmielowiec, J.; Strońska-Pluta, A.; Kowalski, M.T.; Masiak, J.; Trybek, G.; Grzywacz, A. The Influence of Genetic Polymorphic Variability of the Catechol-O-methyltransferase Gene in a Group of Patients with a Diagnosis of Behavioural Addiction, including Personality Traits. Genes 2024, 15, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimber, M.; Schott, B.H.; Wendler, F.; Seidenbecher, C.I.; Behnisch, G.; Macharadze, T.; Bäuml, K.H.; Richardson-Klavehn, A. Prefrontal dopamine and the dynamic control of human long-term memory. Transl. Psychiatry 2011, 1, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, R.H.; Sparling, M.B.; Ryan, L.M.; Xu, K.; Salazar, A.M.; Goldman, D.; Warden, D.L. Association of COMT Val158Met Genotype With Executive Functioning Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 17, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, R.; D’Esposito, M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, e113–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, C.; Botto, A.; Silva, J.R.; Jiménez, J.P.; Luyten, P. Vulnerability or Sensitivity to the Environment? Methodological Issues, Trends, and Recommendations in Gene–Environment Interactions Research in Human Behavior. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humińska-Lisowska, K.; Chmielowiec, K.; Chmielowiec, J.; Strońska-Pluta, A.; Bojarczuk, A.; Dzitkowska-Zabielska, M.; Łubkowska, B.; Spieszny, M.; Surała, O.; Grzywacz, A. Association Between the rs4680 Polymorphism of the COMT Gene and Personality Traits among Combat Sports Athletes. J. Hum. Kinet. 2023, 89, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmijewski, P.; Leońska-Duniec, A.; Stuła, A.; Sawczuk, M. Evaluation of the Association of COMT Rs4680 Polymorphism with Swimmers’ Competitive Performance. Genes 2021, 12, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humińska-Lisowska, K. Dopamine in Sports: A Narrative Review on the Genetic and Epigenetic Factors Shaping Personality and Athletic Performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloyelis, Y.; Asherson, P.; Mehta, M.A.; Faraone, S.V.; Kuntsi, J. DAT1 and COMT effects on delay discounting and trait impulsivity in male adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 2414–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Azevedo, J.N.; Carvalho, C.; Serrão, M.P.; Coelho, R.; Figueiredo-Braga, M.; Vieira-Coelho, M.A. Catechol-O-methyltransferase activity in individuals with substance use disorders: A case control study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, T.M.; Linden, D.E.; Heerey, E.A. COMT val158met predicts reward responsiveness in humans. Genes Brain Behav. 2012, 11, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdejo-García, A.; Lawrence, A.J.; Clark, L. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008, 32, 777–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, R.; Conrod, P.J.; Poline, J.B.; Lourdusamy, A.; Banaschewski, T.; Barker, G.J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Büchel, C.; Byrne, M.; Cummins, T.D.R.; et al. Adolescent impulsivity phenotypes characterized by distinct brain networks. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbeil, O.; Corbeil, S.; Dorval, M.; Carmichael, P.-H.; Giroux, I.; Jacques, C.; Demers, M.-F.; Roy, M.-A. Problem Gambling Associated with Aripiprazole: A Nested Case-Control Study in a First-Episode Psychosis Program. CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulietti, F.; Filipponi, A.; Rosettani, G.; Giordano, P.; Iacoacci, C.; Spannella, F.; Sarzani, R. Pharmacological Approach to Smoking Cessation: An Updated Review for Daily Clinical Practice. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2020, 27, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, C.S.; Bramen, J.; Cohen, M.S.; London, E.D.; Olmstead, R.E.; Gan, J.J.; Costello, M.R.; Shulenberger, S.; Mandelkern, M.A.; Brody, A.L. Effect of Bupropion Treatment on Brain Activation Induced by Cigarette-Related Cues in Smokers. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Grant, J.E.; Adson, D.E.; Shin, Y.C. Double-blind naltrexone and placebo comparison study in the treatment of pathological gambling. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrobus, M.R.; Brazier, J.; Callus, P.; Herbert, A.J.; Stebbings, G.K.; Day, S.H.; Kilduff, L.P.; Bennett, M.A.; Erskine, R.M.; Raleigh, S.M.; et al. Concussion-Associated Gene Variant COMT rs4680 Is Associated With Elite Rugby Athlete Status. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2023, 33, e145–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotypes | Observed (Expected) | Allele Freq | χ2 (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMT rs4680 | ||||

| Mixed addiction n = 128 | A/A | 38 (35.6) | p (A) = 0.53 q (G) = 0.47 | 0.727 (0.3939) |

| G/A | 59 (63.8) | |||

| G/G | 31 (28.6) | |||

| control n = 181 | A/A | 59 (55.2) | p (A) = 0.55 q (G) = 0.45 | 1.272 (0.2594) |

| G/A | 82 (89.5) | |||

| G/G | 40 (36.2) | |||

| COMT rs4680 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypes | Alleles | ||||

| A/A n (%) | G/A n (%) | G/G n (%) | A n (%) | G n (%) | |

| Mixed addiction n = 128 | 38 (29.69%) | 59 (46.09%) | 31 (24.22%) | 135 (52.73%) | 121 (47.26%) |

| Control n = 181 | 59 (32.60%) | 82 (45.30%) | 40 (22.10%) | 200 (55.25%) | 162 (44.75%) |

| χ2 (p value) | 0.3590 0.8357 | 0.3819 (0.5366) | |||

| BIS-11 Scale | Mixed Addictions | Control | Z | (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS-AI | 19.52 ± 4.34 | 17.51 ± 3.57 | 4.386 | 0.0001 # |

| BIS-MI | 26.00 ± 4.83 | 23.45 ± 4.15 | 4.806 | 0.0001 # |

| BIS-NI | 27.72 ± 4.83 | 27.15 ± 4.11 | 1.159 | 0.2465 |

| BIS-11 Total | 73.23 ± 12.00 | 68.01 ± 9.82 | 4.160 | 0.0001 # |

| Comorbid Substance Dependence n (%) | BIS-AI Scale M; Yes vs. No [Z; p-Value] | BIS-MI Scale M; Yes vs. No [Z; p-Value] | BIS-NI Scale M; Yes vs. No [Z; p-Value] | BIS-11 Total Scale M; Yes vs. No [Z; p-Value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates 27 (21%) | 20.15 vs. 19.35 [1.297; p = 0.1947] | 26.74 vs. 25.80 [0.821; p = 0.4119] | 27.78 vs. 27.70 [0.245; p = 0.8062] | 74.63 vs. 72.85 [0.902; p = 0.3669] |

| Cannabinole 93 (73%) | 19.68 vs. 19.09 [−0.706; p = 0.4804] | 26.40 vs. 24.94 [−1.622; p = 0.1047] | 27.86 vs. 27.34 [−0.834; p = 0.4043] | 73.94 vs. 71.34 [−1.406; p = 0.1597] |

| Cocaine 12 (9%) | 20.50 vs. 19.41 [−0.789; p = 0.4302] | 27.25 vs. 25.87 [−0.965; p = 0.3347] | 27.08 vs. 27.78 [0.298; p = 0.7654] | 74.83 vs. 73.06 [−0.768; p = 0.4422] |

| Sedatives and sleeping pills 15 (12%) | 20.33 vs. 19.41 [1.148; p = 0.2509] | 26.20 vs. 25.97 [0.067; p = 0.9468] | 27.13 vs. 27.80 [−0.115; p = 0.9086] | 73.67 vs. 73.17 [0.293; p = 0.7698] |

| Stimulants 96 (75%) | 19.14 vs. 20.66 [−1.731; p = 0.0835] | 25.85 vs. 26.44 [−0.572; p = 0.5671] | 27.47 vs. 28.47 [−1.197; p = 0.2314] | 72.46 vs. 75.53 [−1.310; p = 0.1903] |

| Hallucinogenic 13 (10%) | 19.23 vs. 19.55 [0.406; p = 0.6846] | 26.85 vs. 25.90 [−0.560; p = 0.5754] | 29.15 vs. 27.56 [−1.183; p= 0.2367] | 75.23 vs. 73.00 [−0.513; p = 0.6081] |

| primary schools 64 (50%) vs. secondary 59 (46%) and higher 5 (4%) education | 20.09 vs. 18.94 [−1.315; p= 0.1884] | 26.08 vs. 25.92 [−0.396; p = 0.6924] | 28.02 vs. 27.42 [−0.577; p = 0.5642] | 74.19 vs. 72.27 [−0.715; p = 0.4747] |

| BIS-11 | Group | COMT rs4680 | ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/A n = 97 M ± SD | A/G n = 141 M ± SD | G/G n = 71 M ± SD | Factor | F (p-Value) | η2 | Power (alfa = 0.05) | ||

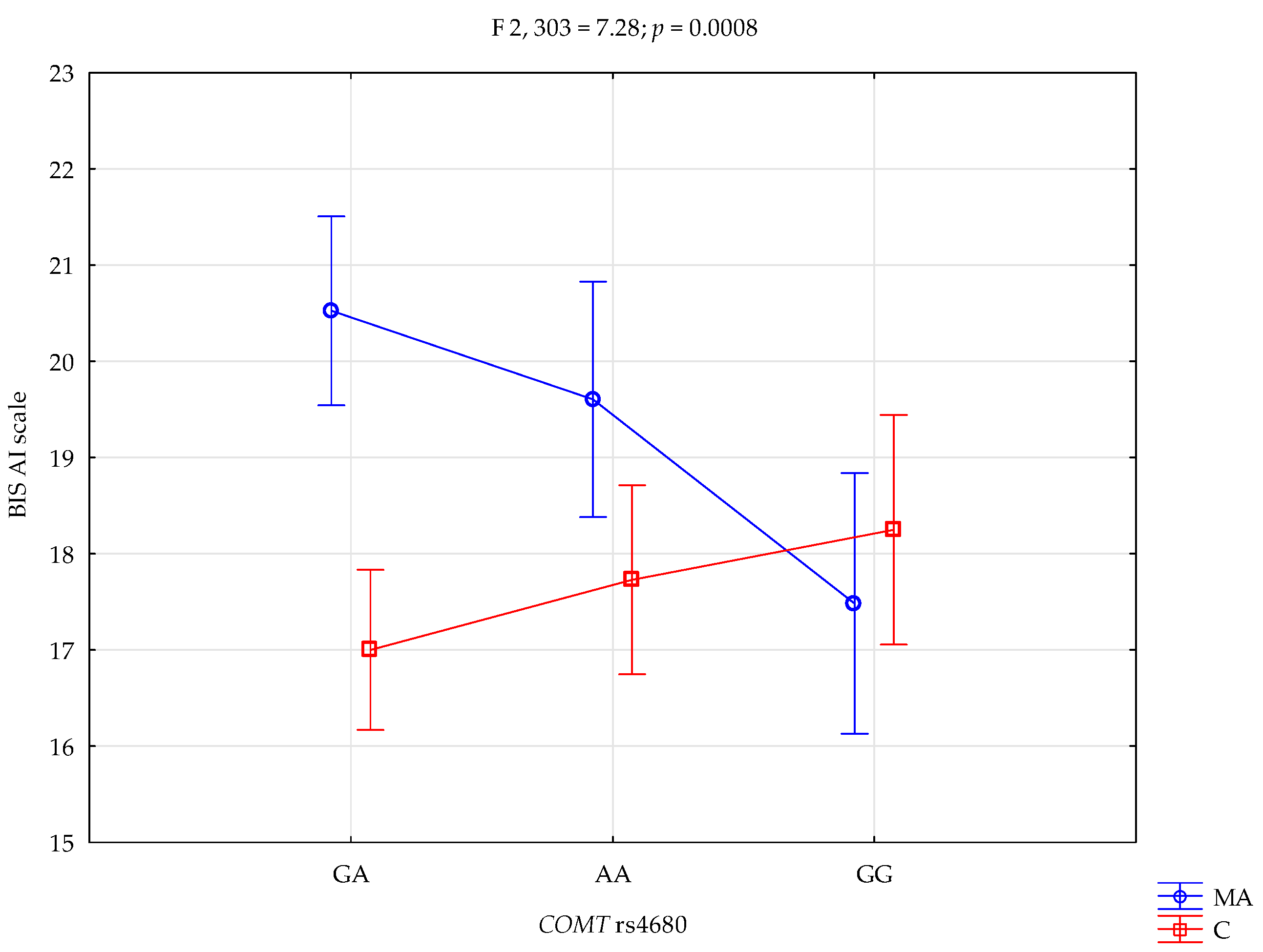

| BIS-AI | Mixed addictions (MA); n = 128 | 19.61 ± 3.72 | 20.53 ± 4.04 | 17.48 ± 4.97 | intercept MA/control COMT rs4680 MA/control × COMT | F1,303 = 6424.47 (p < 0.0001) *# F1,303 = 11.29 (p < 0.0001) *# F2,303 = 1.36 (p = 0.2588) F2,303 = 7.28 (p = 0.0008) *# | 0.955 0.036 0.009 0.046 | 1.000 0.918 0.292 0.935 |

| Control; n = 181 | 17.73 ± 3.41 | 17.00 ± 3.50 | 18.25 ± 3.86 | |||||

| BIS-MI | Mixed addictions (MA); n = 128 | 26.21 ± 5.00 | 26.42 ± 4.59 | 24.94 ± 5.07 | intercept MA/control COMT rs4680 MA/control × COMT | F1,303 = 8612.50 (p < 0.0001) *# F1,303 = 18.04 (p < 0.0001) *# F2,303 = 0.02 (p = 0.9822) F2,303 = 2.32 (p = 0.1001) | 0.966 0.056 0.0001 0.015 | 1.000 0.988 0.053 0.469 |

| Control; n = 181 | 23.27 ± 4.42 | 23.13 ± 3.86 | 24.37 ± 4.27 | |||||

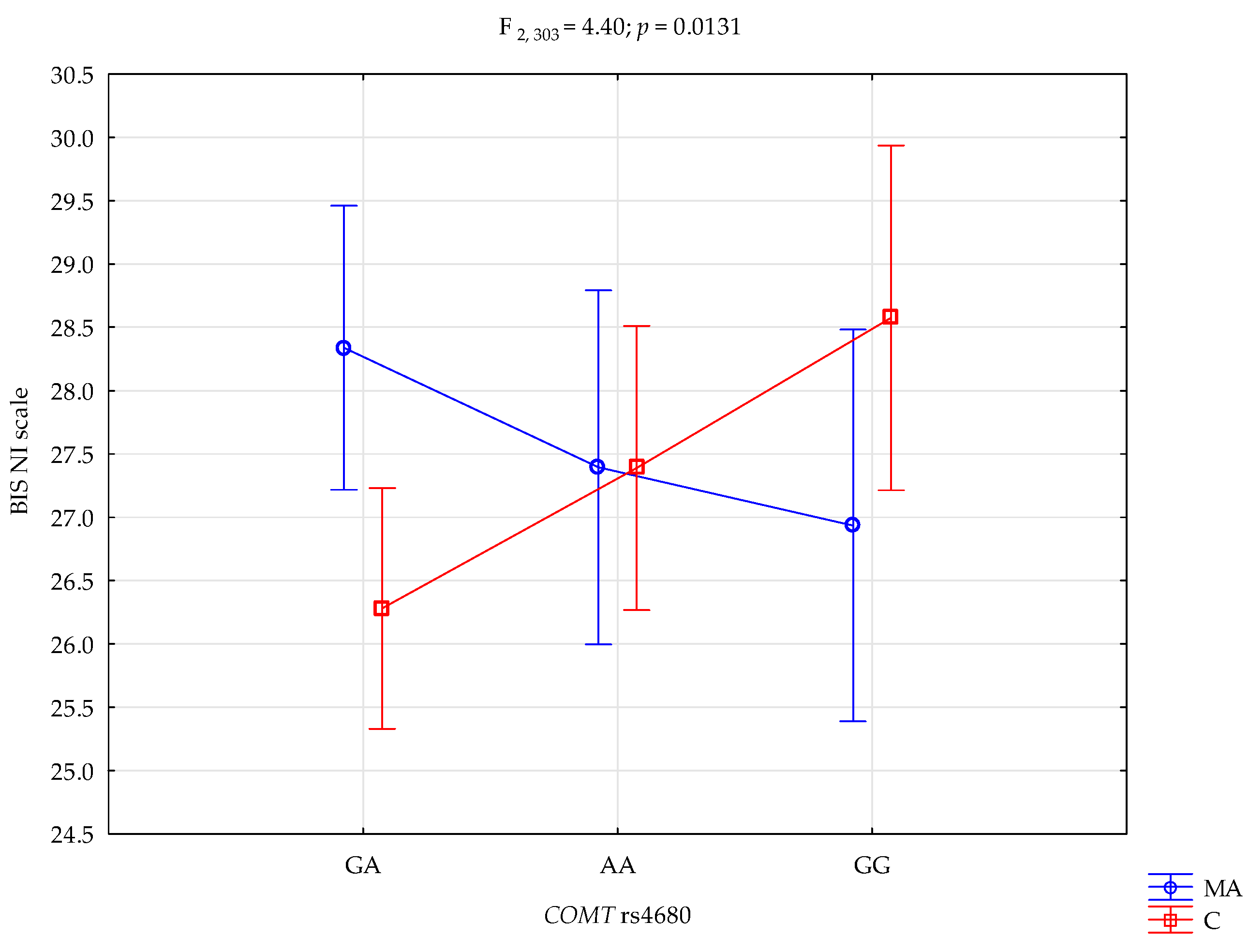

| BIS-NI | Mixed addictions (MA); n = 128 | 27.39 ± 4.80 | 28.34 ± 4.42 | 26.94 ± 5.56 | intercept MA/control COMT rs4680 MA/control × COMT | F1,303 = 10941.17 (p < 0.0001) *# F1,303 = 0.07 (p = 0.7882) F2,303 = 0.25 (p = 0.7811) F2,303 = 4.40 (p = 0.0131) * | 0.973 0.0002 0.001 0.028 | 1.000 0.058 0.089 0.756 |

| Control; n = 181 | 27.39 ± 4.51 | 26.28 ± 3.79 | 28.57 ± 3.74 | |||||

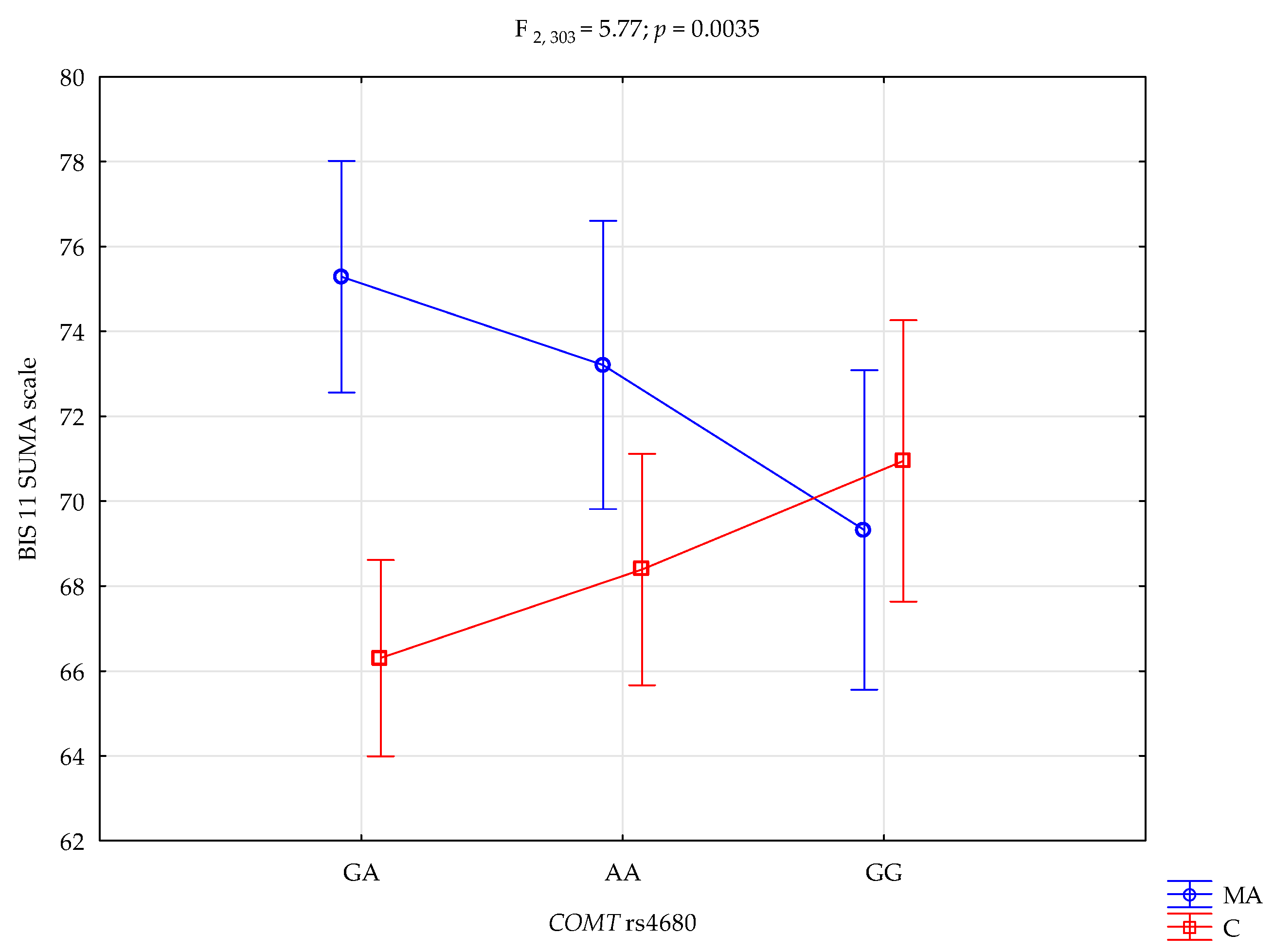

| BIS-11 Total | Mixed addictions (MA); n = 128 | 73.21 ± 11.34 | 75.29 ± 10.76 | 69.32 ± 14.25 | intercept MA/control COMT rs4680 MA/control × COMT | F1,303 = 12202.32 (p < 0.0001) *# F1,303 = 10.09 (p = 0.0016) *# F2,303 = 0.10 (p = 0.9017) F2,303 = 5.77 (p = 0.0035) *# | 0.976 0.032 0.0007 0.037 | 1.000 0.886 0.066 0.867 |

| Control; n = 181 | 68.39 ± 10.84 | 66.30 ± 8.94 | 70.95 ± 9.46 | |||||

| COMT rs4680 and BIS-AI | ||||||

| {1} M = 20.52 | {2} M = 19.60 | {3} M = 17.48 | {4} M = 17.00 | {5} M = 17.73 | {6} M = 18.25 | |

| Mixed addiction A/A {1} | 0.2492 | 0.0004 * | 0.0001 * | 0.0001 * | 0.0040 * | |

| Mixed addiction A/G {2} | 0.0229 * | 0.0006 * | 0.0192 * | 0.1195 | ||

| Mixed addiction G/G {3} | 0.5497 | 0.7734 | 0.4040 | |||

| Control A/A {4} | 0.2661 | 0.0918 | ||||

| Control A/G {5} | 0.5071 | |||||

| Control G/G {6} | ||||||

| COMT rs4680 and BIS-NI | ||||||

| {1} M = 28.34 | {2} M = 27.39 | {3} M = 26.93 | {4} M = 26.28 | {5} M = 27.39 | {6} M = 28.57 | |

| Mixed addiction A/A {1} | 0.3006 | 0.1495 | 0.0062 * | 0.2400 | 0.7926 | |

| Mixed addiction A/G {2} | 0.6650 | 0.1957 | 0.9957 | 0.2350 | ||

| Mixed addiction G/G {3} | 0.4785 | 0.6403 | 0.1187 | |||

| Control A/A {4} | 0.1388 | 0.0070 * | ||||

| Control A/G {5} | 0.1873 | |||||

| Control G/G {6} | ||||||

| COMT rs4680 and BIS-11 Total | ||||||

| {1} M = 75.29 | {2} M = 73.21 | {3} M = 69.32 | {4} M = 66.30 | {5} M = 68.39 | {6} M = 70.95 | |

| Mixed addiction A/A {1} | 0.3489 | 0.0120 * | 0.0001 * | 0.0005 * | 0.0476 * | |

| Mixed addiction A/G {2} | 0.1323 | 0.0011 * | 0.0303 * | 0.3493 | ||

| Mixed addiction G/G {3} | 0.179810 | 0.6931 | 0.5234 | |||

| Control A/A {4} | 0.2522 | 0.0244 * | ||||

| Control A/G {5} | 0.2413 | |||||

| Control G/G {6} | ||||||

| β (p) | BIS-AI Scale | BIS-MI Scale | BIS-NI Scale | BIS-11 Total Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | 15.52 [8.55, 22.48] p = 0.00002 *# | 23.73 [15.54, 31.93] p < 0.00001 *# | 26.21 [18.20, 34.21] p < 0.00001 *# | 65.12 [45.64, 84.59] p < 0.00001 *# |

| MA/C β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | 4.53 [0.04, 9.02] p = 0.04807 * | 1.36 [−3.93, 6.64] p = 0.61399 | 3.01 [−2.15, 8.17] p = 0.25158 | 9.06 [−3.50, 21.62] p = 0.15689 |

| Age β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | −0.13 [−0.42, 0.16] p = 0.39128 | −0.18 [−0.53, 0.17] p = 0.3127 | −0.13 [−0.47, 0.21] p = 0.46919 | −0.43 [−1.26, 0.40] p = 0.31022 |

| COMT rs4680 [A/A] β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | 2.49 [−0.50, 5.48] p = 0.10177 | 0.66 [−2.86, 4.17] p = 0.71380 | 3.27 [−0.16, 6.70] p = 0.06138 | 6.63 [−1.72, 14.98] p = 0.11903 |

| COMT rs4680 [G/G] β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | 5.07 [1.74, 8.40] p = 0.00289 *# | 3.92 [0.01, 7.83 ] p = 0.04932 * | 5.54 [1.72, 9.36] p = 0.00457 *# | 14.29 [4.99, 23.58] p = 0.00269 *# |

| MA/C * Age β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | −0.01 [−0.19, 0.17] p = 0.90513 | 0.09 [−0.12, 0.30] p = 0.40640 | −0.01 [−0.22, 0.20] p = 0.92503 | 0.07 [−0.44, 0.57] p = 0.79599 |

| MA/C * COMT rs4680 [A/A] β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | −1.63 [−3.64, 0.38] p = 0.11121 | −0.43 [−2.79, 1.93] p = 0.71809 | −2.04 [−4.34, 0.27] p = 0.08337 | −4.21 [−9.82, 1.41] p = 0.14134 |

| MA/C * COMT rs4680 [G/G] β [−95% CI, +95% CI] p value | −3.86 [−6.06, −1.65] p = 0.00066 *# | −2.70 [−5.30, −0.11] p = 0.04133 * | −3.28 [−5.82, −0.75] p = 0.01134 *# | −9.74 [−15.91, −3.57] p = 0.00208 *# |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zdunek, G.; Recław, R.; Suchanecka, A.; Chmielowiec, K.; Larysz, D.; Kuczak-Wójtowicz, M.; Łosińska, K.; Chmielowiec, J.; Grzywacz, A. Dopaminergic Genetic Variation and Trait Impulsivity: The Role of COMT rs4680 in Mixed Behavioral and Substance Addictions. Life 2025, 15, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121836

Zdunek G, Recław R, Suchanecka A, Chmielowiec K, Larysz D, Kuczak-Wójtowicz M, Łosińska K, Chmielowiec J, Grzywacz A. Dopaminergic Genetic Variation and Trait Impulsivity: The Role of COMT rs4680 in Mixed Behavioral and Substance Addictions. Life. 2025; 15(12):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121836

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdunek, Gabriela, Remigiusz Recław, Aleksandra Suchanecka, Krzysztof Chmielowiec, Dariusz Larysz, Marta Kuczak-Wójtowicz, Kinga Łosińska, Jolanta Chmielowiec, and Anna Grzywacz. 2025. "Dopaminergic Genetic Variation and Trait Impulsivity: The Role of COMT rs4680 in Mixed Behavioral and Substance Addictions" Life 15, no. 12: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121836

APA StyleZdunek, G., Recław, R., Suchanecka, A., Chmielowiec, K., Larysz, D., Kuczak-Wójtowicz, M., Łosińska, K., Chmielowiec, J., & Grzywacz, A. (2025). Dopaminergic Genetic Variation and Trait Impulsivity: The Role of COMT rs4680 in Mixed Behavioral and Substance Addictions. Life, 15(12), 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121836