Pulmonary Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Inborn Errors of Immunity

| WARNING SIGNS IN CHILDREN |

| 1. ≥4 new ear infections within 1 year |

| 2. ≥2 serious sinus infections within 1 year |

| 3. ≥2 months on antibiotics with little effect |

| 4. ≥2 cases of pneumonia within 1 year |

| 5. Failure of an infant to gain weight or grow normally |

| 6. Recurrent, deep skin, or organ abscesses |

| 7. Persistent thrush in mouth or fungal infection on skin |

| 8. Need for intravenous antibiotics to clear infections |

| 9. ≥2 deep-seated infections including septicemia |

| 10. A family history of PID |

| WARNING SIGNS IN ADULTS |

| 1. ≥2 new ear infections within 1 year |

| 2. ≥2 new sinus infections within 1 year, in the absence of allergy. |

| 3. 1 case of pneumonia per year for >1 year |

| 4. Chronic diarrhea with weight loss |

| 5. Recurrent viral infections (colds, herpes, warts, condyloma) |

| 6. Recurrent need for intravenous antibiotics to clear infections. |

| 7. Recurrent, deep abscesses of the skin or internal organs |

| 8. Persistent thrush or fungal infection on skin or elsewhere |

| 9. Infection with normally harmless tuberculosis-like bacteria |

| 10. A family history of PID |

3. The Spectrum of Pulmonary Manifestations

3.1. Infectious Complications

3.2. Noninfectious Complications

4. Diagnostics and Medical Monitoring

4.1. Medical Imaging

4.2. Immunological Assessment

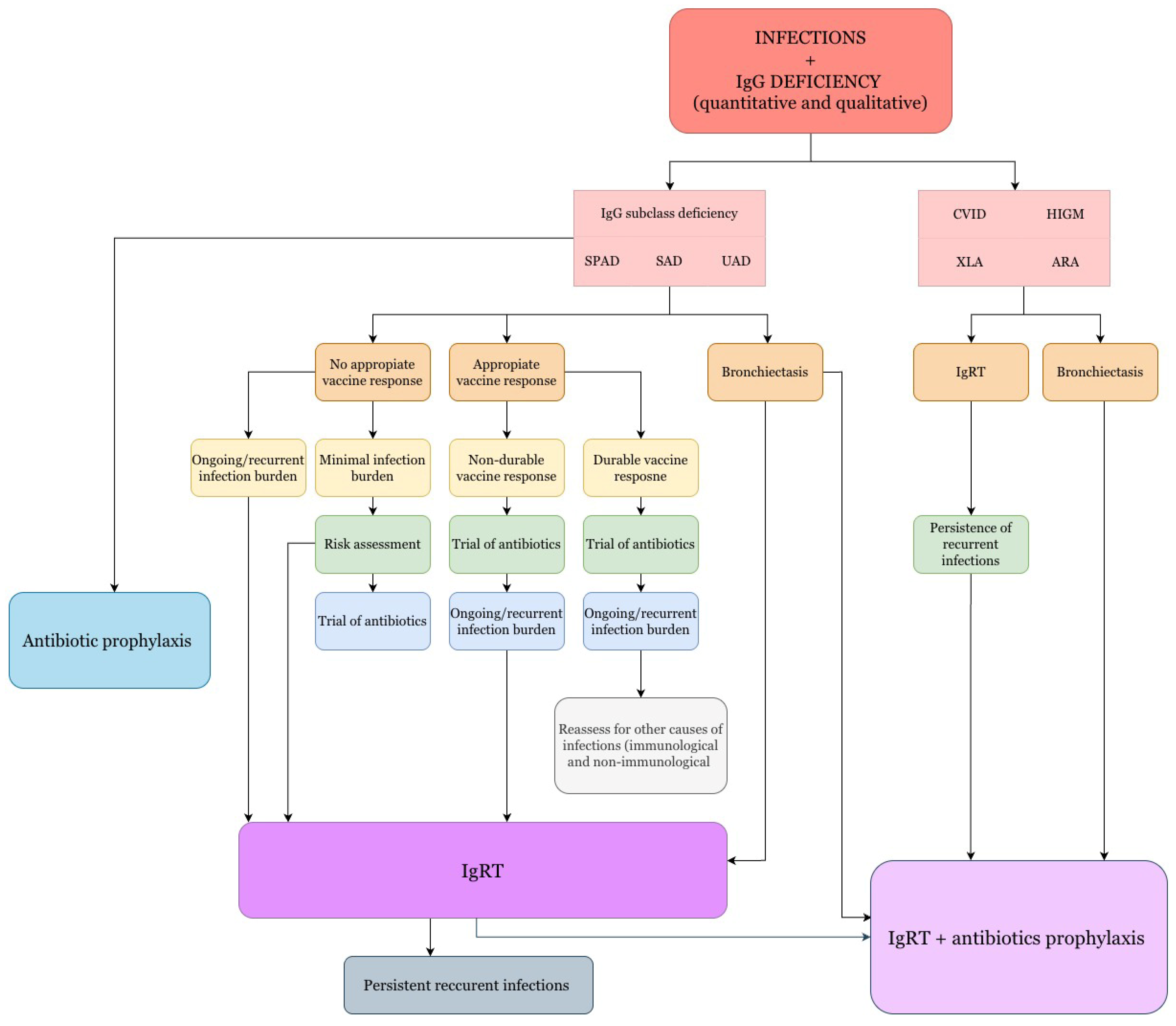

5. Therapeutic Management

- •

- IgG < 200 mg/dL: All patients (except children, who may have physiological hypogammaglobulinemia without severe infections);

- •

- IgG levels 200–500 mg/dL: When deficiency is identified and associated with recurrent infections;

- •

- IgG > 500 mg/dL: When there is a deficiency in the production of antibodies against antigens and severe or recurrent infections [108].

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACWY | Meningococcal conjugate vaccine (serogroups A, C, W, Y) |

| ADA | Adenosine Deaminase Deficiency |

| AD-HIES | Autosomal Dominant Hyper-IgE Syndrome (Job syndrome) |

| AH50 | Alternative Hemolytic Complement Activity |

| AIOLOS | IKZF3, member of the IKAROS family of zinc-finger proteins |

| ALPS-V | Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome, type V (CTLA4 haploinsufficiency) |

| AR | Autosomal Recessive |

| AR-HIES | Autosomal Recessive Hyper-IgE Syndrome |

| ARHGEF1 | Rho Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor 1 |

| AT | Ataxia-Telangiectasia |

| BACH2 | BTB Domain And CNC Homolog 2 |

| BTB Domain | Broad-Complex, Tramtrack, Bric-a-brac Domain (protein–protein interaction) |

| BTK | Bruton Tyrosine Kinase |

| CARD11 | Caspase Recruitment Domain Family Member 11 |

| CCR2 | C-C Chemokine Receptor 2 |

| CD3/CD4/CD8/CD19/CD16/56 | Cluster of Differentiation cell markers (lymphocyte subsets) |

| CF | Cystic Fibrosis |

| CH50 | Total Hemolytic Complement Activity |

| CHH | Cartilage–Hair Hypoplasia |

| CID | Combined Immunodeficiency |

| CNC | Cap’n’collar (transcription factor domain family) |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| CGD | Chronic Granulomatous Disease |

| COPA | Coatomer Protein Complex Subunit Alpha |

| COPG1 | Coatomer Protein Complex Subunit Gamma-1 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CRACR2A | Calcium Release Activated Channel Regulator 2A |

| CSF2R | Colony Stimulating Factor 2 Receptor |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 |

| CVID | Common Variable Immunodeficiency |

| DGS | DiGeorge Syndrome |

| DKCA/DKCB7 | Proteins Related to Dyskeratosis Congenita |

| DN | Dominant Negative |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| DOCK8 | Dedicator of Cytokinesis 8 |

| DPP9 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase 9 |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr Virus |

| Es. | Especially |

| FLT3L | FMS-like Tyrosine Kinase 3 Ligand |

| GATA | Guanine/Adenine/Thymine/Adenine motif |

| GATA2 | GATA Binding Protein 2 |

| GIMAP6 | GTPase of Immunity-Associated Protein 6 |

| GINS | Japanese acronym go-ichi-ni-san (5-1-2-3) |

| GINS4 | GINS Complex Subunit 4 |

| GLILD | Granulomatous-Lymphocytic Interstitial Lung Disease |

| GOF | Gain-of-Function |

| GTP | Guanosine-5′-Triphosphate |

| HCK GOF | Hematopoietic Cell Kinase Gain-of-Function |

| HELIOS | IKZF2, member of the IKAROS family of zinc-finger proteins (ICHAD syndrome) |

| HIES | Hyper-IgE Syndrome |

| HIGM | Hyper-IgM Syndrome |

| HLH | Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| HRCT | High-Resolution Computed Tomography |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex Virus |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| ICHAD | Immunodeficiency, Centromeric Instability, Facial Anomalies |

| IEI | Inborn Errors of Immunity |

| IFN-I | Type I Interferon |

| IgA | Immunoglobulin A |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IgGSD | IgG Subclass Deficiency |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| IKAROS | IKZF1, member of the IKAROS family of zinc-finger proteins |

| IKZF1 | IKAROS Family Zinc Finger 1 |

| IKZF2 | IKAROS Family Zinc Finger 2 |

| IKZF3 | IKAROS Family Zinc Finger 3 |

| IL-21 | Interleukin-21 |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| IL6ST | Interleukin-6 Signal Transducer |

| IUIS | International Union of Immunological Societies |

| IVC | Intravenous (Immunoglobulin therapy context) |

| iRHOM2 | Inactive Rhomboid Protein 2 |

| ITCH | Itchy E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase |

| LD | Linear Dichroism |

| LRBA | Lipopolysaccharide-Responsive and Beige-Like Anchor Protein |

| LTT | Lymphocyte Transformation Test |

| MAC | Mycobacterium Avium Complex |

| MD2 | Myeloid Differentiation Factor 2 |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MHC class I | Major Histocompatibility Complex class I |

| MSMD | Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Disease |

| NBS | Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome |

| NBT | Nitroblue Tetrazolium Test |

| NCK | Non-Catalytic Region of Tyrosine Kinase |

| NCKAP1L | NCK-Associated Protein 1-Like |

| NEMO | NF-κB Essential Modulator |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor κB (Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells) |

| NFAT5 | Nuclear Factor of Activated T Cells 5 |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NK | Natural Killer Cells |

| PCV13 | 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine |

| PCV20 | 20-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine |

| PID | Primary Immunodeficiency |

| PPSV23 | 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCID | Severe Combined Immunodeficiency |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| Tdap | Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis Vaccine |

| TLA | Three-Letter Acronym |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cell |

| TST | Tuberculin Skin Test |

| VZV | Varicella Zoster Virus |

| XLA | X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia |

References

- Gutierrez, M.J.; Nino, G.; Sun, D.; Restrepo-Gualteros, S.; Sadreameli, S.C.; Fiorino, E.K.; Wu, E.; Vece, T.; Hagood, J.S.; Maglione, P.J.; et al. The Lung in Inborn Errors of Immunity: From Clinical Disease Patterns to Molecular Pathogenesis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 150, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odineal, D.D.; Gershwin, M.E. The Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of Autoimmunity in Selective IgA Deficiency. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, C.; Aksentijevich, I.; Bousfiha, A.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Hambleton, S.; Klein, C.; Morio, T.; Picard, C.; Puel, A.; Rezaei, N.; et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2024 Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J. Hum. Immun. 2025, 1, e20250003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E. Future of Therapy for Inborn Errors of Immunity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 63, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Palacín, P.; de Gracia, J.; González-Granado, L.I.; Martín, C.; Rodríguez-Gallego, C.; Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Lung ID-Signal Group. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases in Lung Disease: Warning Signs, Diagnosis and Management. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: An Expanding Universe | Science Immunology. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/sciimmunol.abb1662 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bousfiha, A.A.; Jeddane, L.; Moundir, A.; Poli, M.C.; Aksentijevich, I.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Hambleton, S.; Klein, C.; Morio, T.; Picard, C.; et al. The 2024 Update of IUIS Phenotypic Classification of Human Inborn Errors of Immunity. J. Hum. Immun. 2025, 1, e20250002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.E.; David, C. Inborn Errors of Immunity and Autoimmune Disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 1602–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Esmaeilbeig, M.; Askarisarvestani, A.; Alyasin, S.; Nabavizadeh, S.H. The Prevalence of Allergic Manifestations in Inborn Errors of Immunity: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Immunol. 2025, 26, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiri, A.; Masetti, R.; Conti, F.; Tignanelli, A.; Turrini, E.; Bertolini, P.; Esposito, S.; Pession, A. Inborn Errors of Immunity and Cancer. Biology 2021, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Yadegar, A.; Mardani, M.; Ayati, A.; Abolhassani, H.; Rezaei, N. Organ-Based Clues for Diagnosis of Inborn Errors of Immunity: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11, e833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napiórkowska-Baran, K. Evaluation of the Asthmatic Patient for Primary and Secondary Immunodeficiencies and Importance of Vaccinations in Asthma. In Asthma—Diagnosis, Management and Comorbidities; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Leading the Mission to Cure Primary Immunodeficiency (PI). Available online: https://info4pi.org/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Aranda, C.S.; Guimarães, R.R.; de Gouveia-Pereira Pimentel, M. Combined Immunodeficiencies. J. Pediatr. 2021, 97, S39–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijaro, J.R.; Turner, D.; Pham, Q.; Wherry, E.J.; Lefrançois, L.; Farber, D.L. Cutting Edge: Tissue-Retentive Lung Memory CD4 T Cells Mediate Optimal Protection to Respiratory Virus Infection. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 5510–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.L.; Bickham, K.L.; Thome, J.J.; Kim, C.Y.; D’Ovidio, F.; Wherry, E.J.; Farber, D.L. Lung Niches for the Generation and Maintenance of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.; Muskat, K.; Tippalagama, R.; Sette, A.; Burel, J.; Lindestam Arlehamn, C.S. Classical CD4 T Cells as the Cornerstone of Antimycobacterial Immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2021, 301, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadbudhe, A.M.; Meshram, R.J.; Tidke, S.C. Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) and Its New Treatment Modalities. Cureus 2023, 15, e47759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K.; Govindaraj, G. Infections in Inborn Errors of Immunity with Combined Immune Deficiency: A Review. Pathogens 2023, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funato, N. Craniofacial Phenotypes and Genetics of DiGeorge Syndrome. J. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, G.; Yazdani, R. Predominantly Antibody Deficiencies. Immunol. Genet. J. 2018, 1, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuzzo, G.; Barbieri, A.; Tinazzi, E.; Veneri, D.; Argentino, G.; Moretta, F.; Puccetti, A.; Lunardi, C. Autoimmunity and Infection in Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID). Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskiewicz, A.; Niu, J.; Chang, C. Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome: A Disorder of Immune Dysregulation. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, R.; Barzaghi, F.; Roncarolo, M.-G. From IPEX Syndrome to FOXP3 Mutation: A Lesson on Immune Dysregulation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1417, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickey, D.; Camacho, J.V.; Khan, A.; Kaufman, D. Immunodeficiency: Quantitative and Qualitative Phagocytic Cell Defects. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2024, 45, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanini, L.L.S.; Prader, S.; Siler, U.; Reichenbach, J. Modern Management of Phagocyte Defects. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 28, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglione, P.J.; Simchoni, N.; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Toll-like Receptor Signaling in Primary Immune Deficiencies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1356, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, T.M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Moncada-Velez, M.; Covill, L.E.; Zhang, P.; Alavi Darazam, I.; Bastard, P.; Bizien, L.; Bucciol, G.; et al. Respiratory Viral Infections in Otherwise Healthy Humans with Inherited IRF7 Deficiency. J. Exp. Med. 2022, 219, e20220202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, C.J.A.; Mohamad, S.M.B.; Young, D.F.; Skelton, A.J.; Leahy, T.R.; Munday, D.C.; Butler, K.M.; Morfopoulou, S.; Brown, J.R.; Hubank, M.; et al. Human IFNAR2 Deficiency: Lessons for Antiviral Immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 307ra154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, A.A.; Goldbach-Mansky, R. Genetically Defined Autoinflammatory Diseases. Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coss, S.L.; Zhou, D.; Chua, G.T.; Aziz, R.A.; Hoffman, R.P.; Wu, Y.L.; Ardoin, S.P.; Atkinson, J.P.; Yu, C.-Y. The Complement System and Human Autoimmune Diseases. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 137, 102979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M. Overview of Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes. Blood Res. 2022, 57, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekrvand, S.; Abolhassani, H.; Yazdani, R.; Doffinger, R. Chapter 10—Phenocopies of Inborn Errors of Immunity. In Inborn Errors of Immunity; Aghamohammadi, A., Abolhassani, H., Rezaei, N., Yazdani, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 317–344. ISBN 978-0-12-821028-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzi, N.; Jamee, M.; Bakhtiyari, M.; Rafiemanesh, H.; Zainaldain, H.; Tavakol, M.; Rezaei, A.; Kalvandi, M.; Zian, Z.; Mohammadi, H.; et al. Bronchiectasis in Common Variable Immunodeficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owayed, A.; Al-Herz, W. Sinopulmonary Complications in Subjects With Primary Immunodeficiency. Respir. Care 2016, 61, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devonshire, A.L.; Makhija, M. Approach to Primary Immunodeficiency. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naporowski, P.; Witkowska, D.; Lewandowicz-Uszyńska, A.; Gamian, A. Bacterial, viral and fungal infections in primary immunodeficiency patients. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej 2018, 72. 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabiber, E.; Ilki, A.; Gökdemir, Y.; Vatansever, H.M.; Olgun Yıldızeli, Ş.; Ozen, A. Microbial Isolates and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns in Adults with Inborn Errors of Immunity: A Retrospective Longitudinal Analysis of Sputum Cultures. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 186, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamemi, S.; Jabri, M.A.; Abdalla, E.; Al-Busaidi, I.; Al-Zeedy, K.; Al Yazidi, L. Causes of Mortality in Patients with Inborn Errors of Immunity: An 18-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2025, 25, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costagliola, G.; Consolini, R. Primary Immunodeficiencies: Pathogenetic Advances, Diagnostic and Management Challenges. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöyhönen, L.; Bustamante, J.; Casanova, J.-L.; Jouanguy, E.; Zhang, Q. Life-Threatening Infections Due to Live-Attenuated Vaccines: Early Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity. J. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 39, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenier, P.A.; Brun, A.L.; Longchampt, E.; Lipski, M.; Mellot, F.; Catherinot, E. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases of Adults: A Review of Pulmonary Complication Imaging Findings. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 4142–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plebani, A.; Bondioni, M.P. How Primary Immune Deficiencies Impact the Lung in Childrens. Pediatr. Respir. J. 2024, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, T.J.; Richards, J.C.; Olson, A.L.; Groshong, S.D.; Gelfand, E.W.; Lynch, D.A. Pulmonary Manifestations of Common Variable Immunodeficiency. J. Thorac. Imaging 2018, 33, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperlich, J.M.; Grimbacher, B.; Soetedjo, V. Predictive Factors for and Complications of Bronchiectasis in Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. J. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 42(3), 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, S.E.; Stark, J.M. Pulmonary Manifestations of Immunodeficiency and Immunosuppressive Diseases Other than Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvator, H.; Mahlaoui, N.; Catherinot, E.; Rivaud, E.; Pilmis, B.; Borie, R.; Crestani, B.; Tcherakian, C.; Suarez, F.; Dunogue, B.; et al. Pulmonary Manifestations in Adult Patients with Chronic Granulomatous Disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, U.; Routes, J.M.; Soler-Palacín, P.; Jolles, S. The Lung in Primary Immunodeficiencies: New Concepts in Infection and Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, R.; Abolhassani, H.; Asgardoon, M.; Shaghaghi, M.; Modaresi, M.; Azizi, G.; Aghamohammadi, A. Infectious and Noninfectious Pulmonary Complications in Patients With Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 27, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, M.; Bredius, R.G.M.; van der Burg, M. Future Perspectives of Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Immunity. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrnbecher, T.; Russo, A.; Rohde, G. A Survey of Diagnosis and Therapy of Inborn Errors of Immunity among Practice-Based Physicians and Clinic-Based Pneumologists and Hemato-Oncologists. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1597635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauracher, A.A.; Henrickson, S.E. Leveraging Systems Immunology to Optimize Diagnosis and Treatment of Inborn Errors of Immunity. Front. Syst. Biol. 2022, 2, 910243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Approach to Diagnosing Inborn Errors of Immunity—Rheumatic Disease Clinics. Available online: https://www.rheumatic.theclinics.com/article/S0889-857X(23)00061-3/abstract (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Grumach, A.S.; Goudouris, E.S. Inborn Errors of Immunity: How to Diagnose Them? J. Pediatr. 2021, 97, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.; Ilangovan, G.; Balaganesan, H. Comparative Study of X-ray and High Resolution Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Disease. Int. J. Contemp. Med. Surg. Radiol. 2020, 5(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, K.; Nakamoto, K.; Doi, K.; Kurokawa, N.; Saraya, T.; Ishii, H. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in a Patient with Hyper-IgE Syndrome. Respirol. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e0887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverino, E.; Goeminne, P.C.; McDonnell, M.J.; Aliberti, S.; Marshall, S.E.; Loebinger, M.R.; Murris, M.; Cantón, R.; Torres, A.; Dimakou, K.; et al. European Respiratory Society Guidelines for the Management of Adult Bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Lewis, S.; Wlodarski, M.W. DNA Repair Syndromes and Cancer: Insights Into Genetics and Phenotype Patterns. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 570084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jończyk-Potoczna, K.; Potoczny, J.; Szczawińska-Popłonyk, A. Imaging in Children with Ataxia-Telangiectasia—The Radiologist’s Approach. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 988645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M.J.; Gennery, A.R. Radiation-Sensitive Severe Combined Immunodeficiency: The Arguments for and against Conditioning before Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation—What to Do? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, L.A.; Wisner, E.L.; Gipson, K.S.; Sorensen, R.U. Bronchiectasis in Primary Antibody Deficiencies: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintalib, H.M.; van de Ven, A.; Jacob, J.; Davidsen, J.R.; Fevang, B.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Malphettes, M.; van Montfrans, J.; Maglione, P.J.; Milito, C.; et al. Diagnostic Testing for Interstitial Lung Disease in Common Variable Immunodeficiency: A Systematic Review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1190235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzami, B.; Mohayeji Nasrabadi, M.A.; Abolhassani, H.; Olbrich, P.; Azizi, G.; Shirzadi, R.; Modaresi, M.; Sohani, M.; Delavari, S.; Shahkarami, S.; et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Respiratory Complications in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 505–511.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gracia, J.; Vendrell, M.; Alvarez, A.; Pallisa, E.; Rodrigo, M.-J.; de la Rosa, D.; Mata, F.; Andreu, J.; Morell, F. Immunoglobulin Therapy to Control Lung Damage in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004, 4, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, Z.A.; Abramova, I.; Aldave, J.C.; Al-Herz, W.; Bezrodnik, L.; Boukari, R.; Bousfiha, A.A.; Cancrini, C.; Condino-Neto, A.; Dbaibo, G.; et al. X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA): Phenotype, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Challenges around the World. World Allergy Organ. J. 2019, 12, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzio, S.F.; Palmeira, P.; Moraes-Vasconcelos, D.; Rangel-Santos, A.; de Oliveira, J.B.; Andrade, L.E.C.; Carneiro-Sampaio, M. A Critical Review on the Standardization and Quality Assessment of Nonfunctional Laboratory Tests Frequently Used to Identify Inborn Errors of Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 721289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, B.; Gupta, S. Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Indian J. Pediatr. 2016, 83, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Morena, M.T. Clinical Phenotypes of Hyper-IgM Syndromes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016, 4, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladomenou, F.; Gaspar, B. How to Use Immunoglobulin Levels in Investigating Immune Deficiencies. Arch. Dis. Child.—Educ. Pract. Ed. 2016, 101, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.R.; van der Burgh, A.C.; Peeters, R.P.; van Hagen, P.M.; Dalm, V.A.S.H.; Chaker, L. Determinants of Serum Immunoglobulin Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 664526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solanki, A.S.; Sharma, N.; Thadani, D. Pattern of Serum Protein Electrophoresis: Advances in Laboratory Medicine. J. Med. Evid. 2025, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S.; Borrell, R.; Zouwail, S.; Heaps, A.; Sharp, H.; Moody, M.; Selwood, C.; Williams, P.; Phillips, C.; Hood, K.; et al. Calculated Globulin (CG) as a Screening Test for Antibody Deficiency. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 177, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzer, U.; Sack, U.; Fuchs, I. Flow Cytometry in the Diagnosis and Follow Up of Human Primary Immunodeficiencies. EJIFCC 2019, 30, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tofighi Zavareh, F.; Mirshafiey, A.; Yazdani, R.; Keshtkar, A.A.; Abolhassani, H.; Bagheri, Y.; Rezaei, A.; Delavari, S.; Rezaei, N.; Aghamohammadi, A. Lymphocytes Subsets in Correlation with Clinical Profile in CVID Patients without Monogenic Defects. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 17, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrón-Ruiz, L.; López-Herrera, G.; Vargas-Hernández, A.; Mogica-Martínez, D.; García-Latorre, E.; Blancas-Galicia, L.; Espinosa-Rosales, F.J.; Santos-Argumedo, L. Lymphocytes and B-Cell Abnormalities in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID). Allergol. Immunopathol. 2014, 42, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayani, I.; Susmiati; EWinarti; Sulistyawati, W. The Correlation between CD4 Count Cell and Opportunistic Infection among HIV/AIDS Patients. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1569, 032066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.T.; Söderström, A.; Jørgensen, C.S.; Larsen, C.S.; Petersen, M.S.; Bernth Jensen, J.M. Diagnostic Vaccination in Clinical Practice. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 717873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.K. Application of Vaccine Response in the Evaluation of Patients with Suspected B-Cell Immunodeficiency: Assessment of Responses and Challenges with Interpretation. J. Immunol. Methods 2022, 510, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázár-Molnár, E.; Peterson, L.K. Clinical Utility of the Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay, an in Vitro Functional Readout of the Adaptive Immune Response. J. Immunol. Methods 2025, 537, 113819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezahosseini, O.; Møller, D.L.; Knudsen, A.D.; Sørensen, S.S.; Perch, M.; Gustafsson, F.; Rasmussen, A.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Nielsen, S.D. Use of T Cell Mediated Immune Functional Assays for Adjustment of Immunosuppressive or Anti-Infective Agents in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 567715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Kelly, D.F.; Pollard, A.J.; Trück, J. Polysaccharide-Specific B Cell Responses to Vaccination in Humans. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orange, J.S.; Ballow, M.; Stiehm, E.R.; Ballas, Z.K.; Chinen, J.; De La Morena, M.; Kumararatne, D.; Harville, T.O.; Hesterberg, P.; Koleilat, M.; et al. Use and Interpretation of Diagnostic Vaccination in Primary Immunodeficiency: A Working Group Report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, S1–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farruggia, P. Immune Neutropenias of Infancy and Childhood. World J. Pediatr. 2016, 12, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, J.P.; Westerbeek, E.A.M.; van der Klis, F.R.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; van Elburg, R.M. Transplacental Transport of IgG Antibodies to Preterm Infants: A Review of the Literature. Early Hum. Dev. 2011, 87, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turczyńska, K.; Siebert, J. Immunolog kliniczny potrzebny od zaraz? Forum Med. Rodz. 2020, 14, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yang, W.; Lau, Y. NGS Data Analysis for Molecular Diagnosis of Inborn Errors of Immunity. Semin. Immunol. 2024, 74–75, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal Singh, S.; Dammeijer, F.; Hendriks, R.W. Role of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase in B Cells and Malignancies. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egg, D.; Rump, I.C.; Mitsuiki, N.; Rojas-Restrepo, J.; Maccari, M.-E.; Schwab, C.; Gabrysch, A.; Warnatz, K.; Goldacker, S.; Patiño, V.; et al. Therapeutic Options for CTLA-4 Insufficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamee, M.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Sharifinejad, N.; Zaki-Dizaji, M.; Matloubi, M.; Hasani, M.; Baris, S.; Alsabbagh, M.; Lo, B.; Azizi, G. Comprehensive Comparison between 222 CTLA-4 Haploinsufficiency and 212 LRBA Deficiency Patients: A Systematic Review. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021, 205, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, L.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Holland, S.M. Germline GATA2 Mutation and Bone Marrow Failure. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 32, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.K.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Huh, H.J.; Kang, J.-M.; Kim, Y.-J.; Yoo, K.H.; Ahn, K.; Cho, H.K.; Peck, K.R.; et al. Flow Cytometry for the Diagnosis of Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases: A Single Center Experience. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2020, 12, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Arora, K.; Shandilya, J.; Vignesh, P.; Suri, D.; Kaur, G.; Rikhi, R.; Joshi, V.; Das, J.; Mathew, B.; et al. Flow Cytometry for Diagnosis of Primary Immune Deficiencies-A Tertiary Center Experience From North India. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lye, S.J. The Immune Potential of Decidua-Resident CD16+CD56+ NK Cells in Human Pregnancy. Hum. Immunol. 2021, 82, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pac, M.; Mikołuć, B.; Pietrucha, B.; Wolska-Kuśnierz, B.; Piątosa, B.; Michałkiewicz, J.; Gregorek, H.; Bernatowska, E. Clinical and Immunological Analysis of Patients with X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: Single Center Experience. Central Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 3, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlollahi, M.R.; Pourpak, Z.; Hamidieh, A.A.; Movahedi, M.; Houshmand, M.; Badalzadeh, M.; Nourizadeh, M.; Mahloujirad, M.; Arshi, S.; Nabavi, M.; et al. Clinical, Laboratory, and Molecular Findings for 63 Patients With Severe Combined Immunodeficiency: A Decade’s Experience. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 27, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, A.; Jindal, A.K.; Suri, D.; Vignesh, P.; Gupta, A.; Saikia, B.; Minz, R.W.; Banday, A.Z.; Tyagi, R.; Arora, K.; et al. Clinical and Genetic Profile of X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: A Multicenter Experience From India. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 612323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisco, A.; Ortega-Villa, A.M.; Mystakelis, H.; Anderson, M.V.; Mateja, A.; Laidlaw, E.; Manion, M.; Roby, G.; Higgins, J.; Kuriakose, S.; et al. Reappraisal of Idiopathic CD4 Lymphocytopenia at 30 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1680–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmer, T.; Neuenhahn, M.; Held, J.; Rasch, S.; Schmid, R.M.; Huber, W. Comparison of 1,3-β-d-Glucan with Galactomannan in Serum and Bronchoalveolar Fluid for the Detection of Aspergillus Species in Immunosuppressed Mechanical Ventilated Critically Ill Patients. J. Crit. Care 2016, 36, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezzo, A.; Cavaliere, F.M.; Milito, C.; Bilotta, C.; Iacobini, M.; Quinti, I. Intravenous Immunoglobulin Replacement Treatment Reduces in Vivo Elastase Secretion in Patients with Common Variable Immune Disorders. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, A.; Bangs, C.; Shillitoe, B.; Edgar, J.D.; Burns, S.O.; Thomas, M.; Alachkar, H.; Buckland, M.; McDermott, E.; Arumugakani, G.; et al. Bronchiectasis and Deteriorating Lung Function in Agammaglobulinaemia despite Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 191, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronchiectasis and Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy. Available online: https://www.aaaai.org/allergist-resources/ask-the-expert/answers/2023/bronchiectasis (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Baris, S.; Ercan, H.; Cagan, H.H.; Ozen, A.; Karakoc-Aydiner, E.; Ozdemir, C.; Bahceciler, N.N. Efficacy of Intravenous Immunoglobulin Treatment in Children with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 21, 514–521. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Pattanaik, D.; Krishnaswamy, G. Common Variable Immune Deficiency and Associated Complications. Chest 2019, 156, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugham, V.B.; Rayi, A. Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barahona Afonso, A.F.; João, C.M.P. The Production Processes and Biological Effects of Intravenous Immunoglobulin. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, P.D.; Smith, L.; Usher, J.; Donati, M.; Johnston, S.L.; Gompels, M.M.; Unsworth, D.J. False Interpretation of Diagnostic Serology Tests for Patients Treated with Pooled Human Immunoglobulin G Infusions: A Trap for the Unwary. Clin. Med. 2015, 15, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, J.; Kyle, B.D. Clinical False Positives Resulting from Recent Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy: Case Report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condino-Neto, A.; Costa-Carvalho, B.T.; Grumach, A.S.; King, A.; Bezrodnik, L.; Oleastro, M.; Leiva, L.; Porras, O.; Espinosa-Rosales, F.J.; Franco, J.L.; et al. Guidelines for the Use of Human Immunoglobulin Therapy in Patients with Primary Immunodeficiencies in Latin America. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2014, 42, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, B.M.; Kleine Budde, I.; de Vries, E.; Ten Berge, I.J.M.; Bredius, R.G.M.; van Deuren, M.; van Dissel, J.T.; Ellerbroek, P.M.; van der Flier, M.; van Hagen, P.M.; et al. Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy Versus Antibiotic Prophylaxis as Treatment for Incomplete Primary Antibody Deficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 41, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikos, A.; Albur, M.; Gompels, M.; Barnaby, C.L.; Allan, S.; Johnston, S. Antibiotic Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Respiratory Tract Infections in Antibody Deficient Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Pract. 2020, 7–8, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofael, S.; Leboreiro Babe, C.; Davrandi, M.; Kondratiuk, A.L.; Cleaver, L.; Ahmed, N.; Atkinson, C.; McHugh, T.; Lowe, D.M. Antibiotic Resistance, Bacterial Transmission and Improved Prediction of Bacterial Infection in Patients with Antibody Deficiency. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, A.F.; Holland, S.M. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Primary Immunodeficiencies. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 9, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler-Laporte, G.; Smyth, E.; Amar-Zifkin, A.; Cheng, M.P.; McDonald, E.G.; Lee, T.C. Low-Dose TMP-SMX in the Treatment of Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Shrivastava, M.; Whiteway, M.; Jiang, Y. Candida Albicans Targets That Potentially Synergize with Fluconazole. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olum, R.; Baluku, J.B.; Kazibwe, A.; Russell, L.; Bongomin, F. Tolerability of Oral Itraconazole and Voriconazole for the Treatment of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Gerriets, V. Acyclovir. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ganciclovir and Valganciclovir: An Overview—UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ganciclovir-and-valganciclovir-an-overview (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Pecoraro, A.; Crescenzi, L.; Galdiero, M.R.; Marone, G.; Rivellese, F.; Rossi, F.W.; de Paulis, A.; Genovese, A.; Spadaro, G. Immunosuppressive Therapy with Rituximab in Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2019, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessarin, G.; Baronio, M.; Gazzurelli, L.; Rossi, S.; Chiarini, M.; Moratto, D.; Giliani, S.C.; Bondioni, M.P.; Badolato, R.; Lougaris, V. Rituximab Monotherapy Is Effective as First-Line Treatment for Granulomatous Lymphocytic Interstitial Lung Disease (GLILD) in CVID Patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbsky, J.W.; Hintermeyer, M.K.; Simpson, P.M.; Feng, M.; Barbeau, J.; Rao, N.; Cool, C.D.; Sosa-Lozano, L.A.; Baruah, D.; Hammelev, E.; et al. Rituximab and Antimetabolite Treatment of Granulomatous and Lymphocytic Interstitial Lung Disease in Common Variable Immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 704–712.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.Y.; Betschel, S.; Grunebaum, E. Monitoring Patients with Uncomplicated Common Variable Immunodeficiency: A Systematic Review. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S.; Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Quinti, I.; Soler-Palacín, P.; Agostini, C.; Florkin, B.; Couderc, L.-J.; Brodszki, N.; Jones, A.; Longhurst, H.; et al. Screening Protocols to Monitor Respiratory Status in Primary Immunodeficiency Disease: Findings from a European Survey and Subclinical Infection Working Group. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017, 190, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Jimenez, O.; Restrepo-Gualteros, S.; Nino, G.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Sullivan, K.E.; Fuleihan, R.L.; Gutierrez, M.J. Respiratory Comorbidities Associated with Bronchiectasis in Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency in the USIDNET Registry. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43(8), 2208–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobh, A.; Bonilla, F.A. Vaccination in Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016, 4, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, F.A. Update: Vaccines in Primary Immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, M.S.B.; Yildiz, R.; Keskin, G.; Altiner, S. Vaccination against Respiratory Tract Pathogens in Primary Immune Deficiency Patients Receiving Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy. Tuberk Toraks 2024, 72, 202401813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, V.H.D.; Upton, J.E.M.; Derfalvi, B.; Hildebrand, K.J.; McCusker, C. Inborn Errors of Immunity (Primary Immunodeficiencies). Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2025, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A. Vaccination in Patients with Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders. Immunol. Genet. J. 2020, 3, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, C.; Upton, J.; Warrington, R. Primary Immunodeficiency. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyts, I.; Bousfiha, A.; Duff, C.; Singh, S.; Lau, Y.L.; Condino-Neto, A.; Bezrodnik, L.; Ali, A.; Adeli, M.; Drabwell, J. Primary Immunodeficiencies: A Decade of Progress and a Promising Future. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 625753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estirado, A.D.; García, G.S.; Aragonés, J.H.; Colino, C.G.; Seoane-Reula, E.; Fernández, C.M. Outcomes and Impact of Multidisciplinary Team Care on Immunologic and Hemato-Oncologic Pediatric Patients. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2023, 51, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israni, M.; Nicholson, B.; Mahlaoui, N.; Obici, L.; Rossi-Semerano, L.; Lachmann, H.; Hayward, G.; Avramovič, M.Z.; Guffroy, A.; Dalm, V.; et al. Current Transition Practice for Primary Immunodeficiencies and Autoinflammatory Diseases in Europe: A RITA-ERN Survey. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía González, M.A.; Quijada Morales, P.; Escobar, M.Á.; Juárez Guerrero, A.; Seoane-Reula, M.E. Navigating the Transition of Care in Patients with Inborn Errors of Immunity: A Single-Center’s Descriptive Experience. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1263349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshko, D.; Kulbachinskaya, E.; Korsunskiy, I.; Kondrikova, E.; Pulvirenti, F.; Quinti, I.; Blyuss, O.; Dunn Galvin, A.; Munblit, D. Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adults with Primary Immunodeficiencies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1929–1957.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.S.; Henrickson, S.E. Defining and Targeting Patterns of T Cell Dysfunction in Inborn Errors of Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 932715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviano, G.; Chiesa, R.; Feuchtinger, T.; Vickers, M.A.; Dickinson, A.; Gennery, A.R.; Veys, P.; Todryk, S. Adoptive T Cell Therapy Strategies for Viral Infections in Patients Receiving Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cells 2019, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Type of Immunodeficiency | Key Cells/Systems Affected | Typical Pathogens | Main Pulmonary Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humoral (antibody-related) | B lymphocytes, antibodies (IgG, IgA, IgM) | Encapsulated bacteria: Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Viruses: Enteroviruses | Recurrent otitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, pneumonia; gastrointestinal infections |

| Cellular (T-cell) | T lymphocytes | Opportunistic bacteria: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Staphylococcus spp., Mycobacterium spp., Listeria spp. Viruses: CMV, HSV, VZV; Fungi: Candida spp., Pneumocystis jirovecii | Disseminated viral and fungal infections, Opportunistic bacterial infections, chronic diarrhea, growth failure |

| Phagocytic defects | Neutrophils, macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus, Serratia marcescens, Aspergillus spp. | Skin/soft-tissue abscesses, liver and lung infections |

| Complement deficiency—terminal pathway (C5–C9) | Terminal complement components | Neisseria meningitidis | Recurrent meningitis, sepsis |

| Complement deficiency—classical pathway (C1q, C2, C4) | Classical complement proteins | S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae | Recurrent respiratory infections |

| Complement deficiency—C3 | Central element of all pathways | S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae | Severe purulent infections |

| Defects in intrinsic/innate immunity | Neutrophils, macrophages, NK cells, TLR signaling, IFN-I pathway | Bacteria: pyogenic bacteria (streptococci, staphylococci), mycobacteria (M. bovis BCG, atypical), Salmonella Viruses: herpesviruses (HSV, EBV, CMV), respiratory viruses (influenza, SARS-CoV-2) Fungi: Candida (selected defects) | Severe recurrent bacterial, viral, and fungal infections from early childhood |

| Diseases of immune dysregulation | Treg, cytotoxic T cells, NK cells | Often EBV | Autoimmunity (cytopenias, IBD), lymphoproliferation, HLH |

| Combined immunodeficiencies with syndromic features | T and B lymphocytes | Encapsulated bacteria: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae Viruses: VZV, EBV, HSV, CMV Opportunistic fungi: Pneumocystis jirovecii | Recurrent infections, dysmorphic features, congenital heart/skin/bone defects, malignancy |

| Autoinflammatory disorders | Monocytes, neutrophils, inflammasomes | None (sterile inflammation) | Recurrent fever attacks, rashes, arthritis/serositis, risk of amyloidosis |

| Bone marrow failure | Hematopoietic stem cells (all blood cell lines) | Opportunistic bacteria: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. Fungi: Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., Pneumocystis jirovecii Viruses: CMV, HSV, VZV, EBV | Pancytopenia with anemia, neutropenia, infections, cancer predisposition |

| Phenocopies of IEI | Autoantibodies or somatic mutations | Pathogens as in the corresponding genetic IEI (e.g., mycobacteria, fungi, viruses) | IEI-like symptoms, typically adult onset |

| PULMONARY INVOLVEMENT | ASSOCIATED INBORN ERRORS OF IMMUNITY |

|---|---|

| Asthma | CHH, CVID, DOCK8 deficiency, SIgAD, SIgMD, STAT6 GOF |

| Bronchiectasis | ARHGEF1 deficiency, Bloom syndrome, CF, CGD, CHH, CVID, defects of antigen presentation, GIMAP6 deficiency, HIES, IgGSD, IL6ST partial deficiency, NCKAP1L deficiency, NFATC1 deficiency, PAD, PCD, PGM3 deficiency, PGM3 deficiency, SRP19/SRPRA deficiency, STAT6 GOF, TRAF3 haploinsufficiency |

| Bronchitis | CVID, DPP9 deficiency, defects of antigen presentation, IgG3 deficiency, IgG4 deficiency, SIgAD, XLA |

| Chronic cough & pleurisy | CVID, SIgAD, XLA |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | NFKB1 deficiency |

| Granulomas | RHOH deficiency, CVID |

| Interstitial lung disease | AR STING-associated vasculopathy, infantile-onset (SAVI), COPA Syndrome, CTLA4 haploinsufficiency (ALPS-V), ITCH deficiency (early onset), STAT5B deficiency, STAT6 GOF |

| Lung abscesses | AD-HIES STAT3 deficiency (Job syndrome), AR-HIES, ZNF341 deficiency |

| Organizing pneumonia or bronchiolitis obliterans | CID, CVID, DGS, PAD, WAS, XLP |

| Pneumatoceles | AD-HIES STAT3 deficiency (Job syndrome), AR-HIES, IL6ST partial deficiency, ZNF341 deficiency, iRHOM deficiency |

| Pneumonia | ADA deficiency, AIOLOS deficiency, AR STING-associated vasculopathy, infantile-onset (SAVI), AT, BACH2 deficiency, CARD11 deficiency (es. Pneumocystis jirovecii), CGD, CID, complement deficiency, COPG1 deficiency, CRACR2A deficiency, CVID, defects of antigen presentation, DPP9 deficiency, FLT3L deficiency, GIMAP6 Deficiency, GINS4 deficiency, HELIOS deficiency, iRHOM deficiency, IKAROS deficiency, IKZF2 DN (ICHAD syndrome), IL-21 deficiency, IL6 receptor deficiency, IL6ST partial deficiency, IRF4 multimorphic mutation (early onset with Pneumocystis jirovecii), ITCH deficiency (early onset), Kabuki syndrome (type 1 and 2), MD2 deficiency, MHC class I deficiency, NBS, NCKAP1L deficiency, NEMO deficiency, NFAT5 haploinsufficiency, NFATC1 deficiency (early onset), NFKB1 deficiency, NFKB2 deficiency, PAD, PCD, PGM3 deficiency, PLAID, PRIM1, PU1 deficiency, RAC2 deficiency, RASGRP1 deficiency, reduced serum Ig-G2 level, SASH3 deficiency, SIgAD, SLC19A1/PCFT deficiency causing hereditary folate malabsorption, SRP19 / SRPRA deficiency, STAT5B deficiency, STAT6 GOF, TLR3 deficiency (severe pulmonary influenza), TRAF3 haploinsufficiency, TWEAK deficiency, WAS, X-linked HIGM, XLA, ZNF341 deficiency |

| Progressive polycystic lung disease | CCR2 |

| Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis | CCR2, CSF2R deficiency, GATA2 deficiency, SLC7A7 deficiency |

| Pulmonary aspergilosis | AD-HIES STAT3 deficiency (Job syndrome), IL6ST partial deficiency |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | DKCA, DKCB7, HCK GOF, Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome type 2 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | GIMAP6 deficiency, PSMB9 deficiency (G156D) |

| Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis | NLRP1 GOF |

| Susceptibility to mycobacteria | MSMD |

| Vasculitis of lungs with pulmonary hypertension | GIMAP6 deficiency |

| IEI DIAGNOSTICS | REMARKS | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical manifestations | General symptoms:

Pulmonary manifestation (especially in combination with at least one of the mentioned):

| |

| Laboratory tests | ASSESSMENT OF HUMORAL IMMUNITY:

ASSESSMENT OF CELLULAR IMMUNITY:

ASSESSMENT OF PHAGOCYTIC CELLS:

ASSESSMENT OF THE COMPLEMENT SYSTEM:

| Proteinogram:

Secondary immunodeficiencies should be excluded. |

| Imaging tests |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

| PULMONARY COMPLICATIONS MONITORING | REMARKS | |

| Clinical indicators |

| |

| Laboratory tests |

| Indications and frequency determined individually |

| Imaging tests |

|

|

| Microbiological testing |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Napiorkowska-Baran, K.; Cofta, S.; Treichel, P.; Tykwinska, M.; Lis, K.; Matyja-Bednarczyk, A.; Szymczak, B.; Szota, M.; Slawatycki, J.; Kulakowski, M.; et al. Pulmonary Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights. Life 2025, 15, 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121838

Napiorkowska-Baran K, Cofta S, Treichel P, Tykwinska M, Lis K, Matyja-Bednarczyk A, Szymczak B, Szota M, Slawatycki J, Kulakowski M, et al. Pulmonary Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights. Life. 2025; 15(12):1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121838

Chicago/Turabian StyleNapiorkowska-Baran, Katarzyna, Szczepan Cofta, Paweł Treichel, Marta Tykwinska, Kinga Lis, Aleksandra Matyja-Bednarczyk, Bartłomiej Szymczak, Maciej Szota, Jozef Slawatycki, Michal Kulakowski, and et al. 2025. "Pulmonary Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights" Life 15, no. 12: 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121838

APA StyleNapiorkowska-Baran, K., Cofta, S., Treichel, P., Tykwinska, M., Lis, K., Matyja-Bednarczyk, A., Szymczak, B., Szota, M., Slawatycki, J., Kulakowski, M., & Bartuzi, Z. (2025). Pulmonary Manifestations of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Insights. Life, 15(12), 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121838