Biofabrication of Terminalia ferdinandiana-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles and Their Anticancer Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Preparation of the Leaf and Fruit Extract

2.3. The Optimization Process of AuNPs

2.4. Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles

2.5. Antioxidant Activity Assay

2.6. Anticancer Assays

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

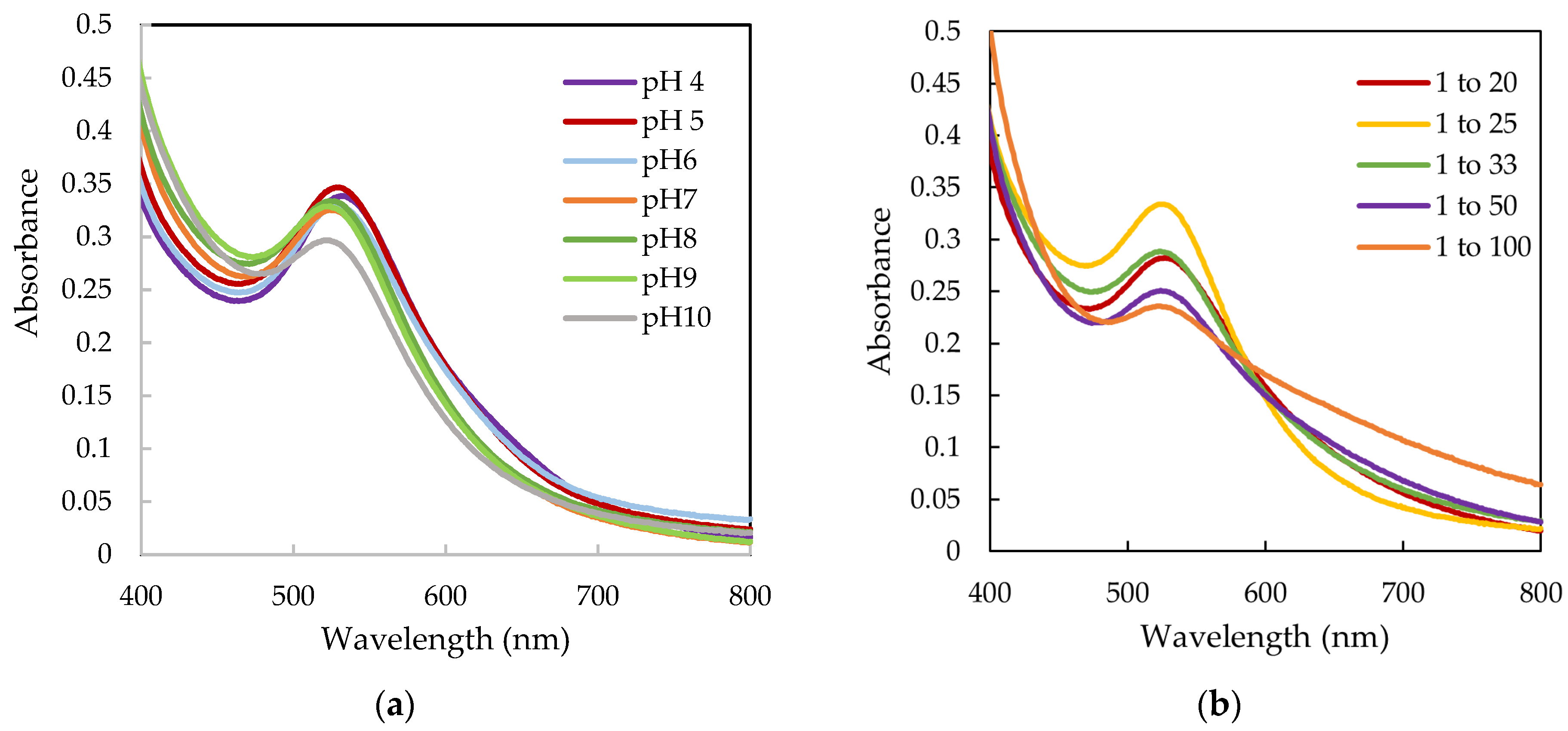

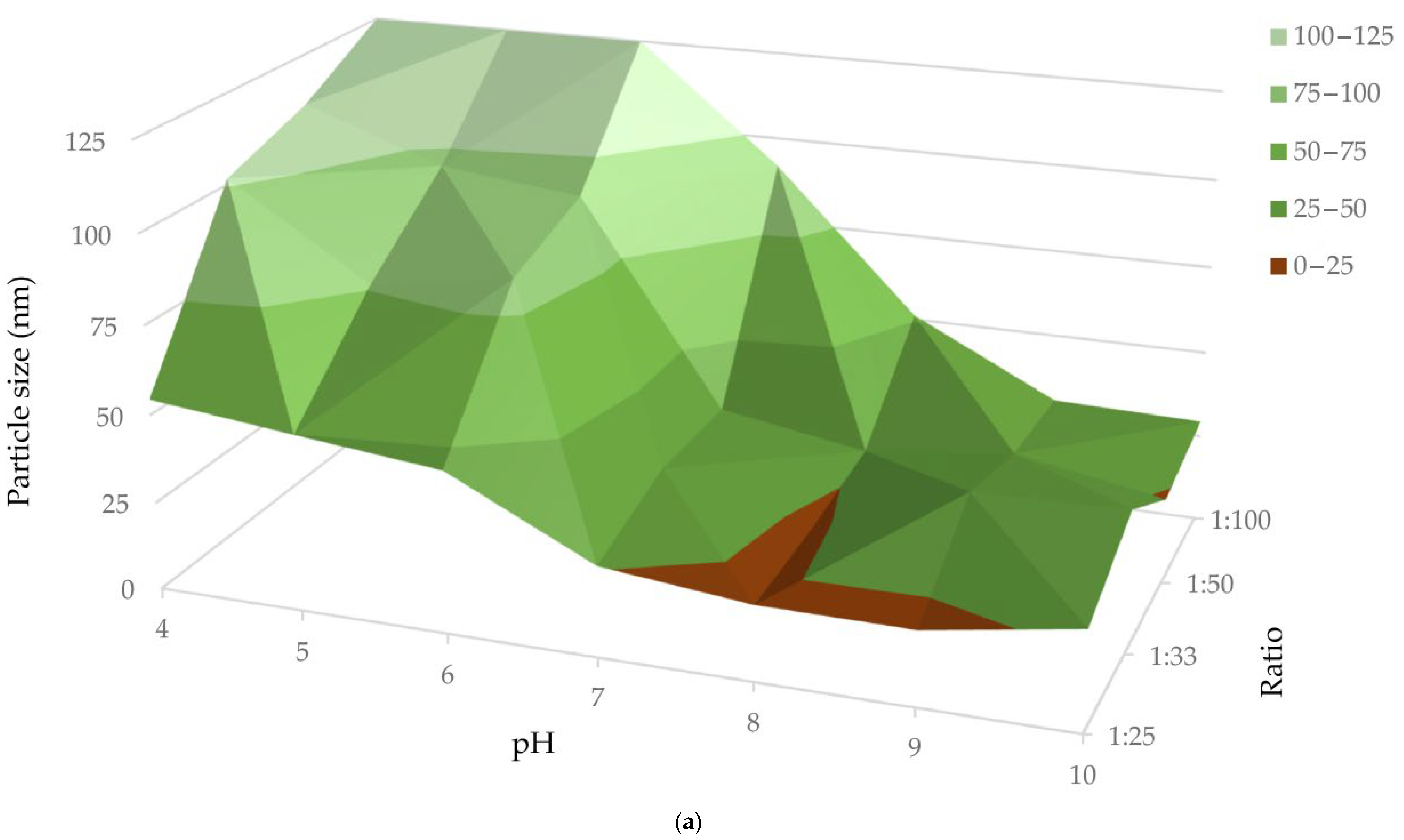

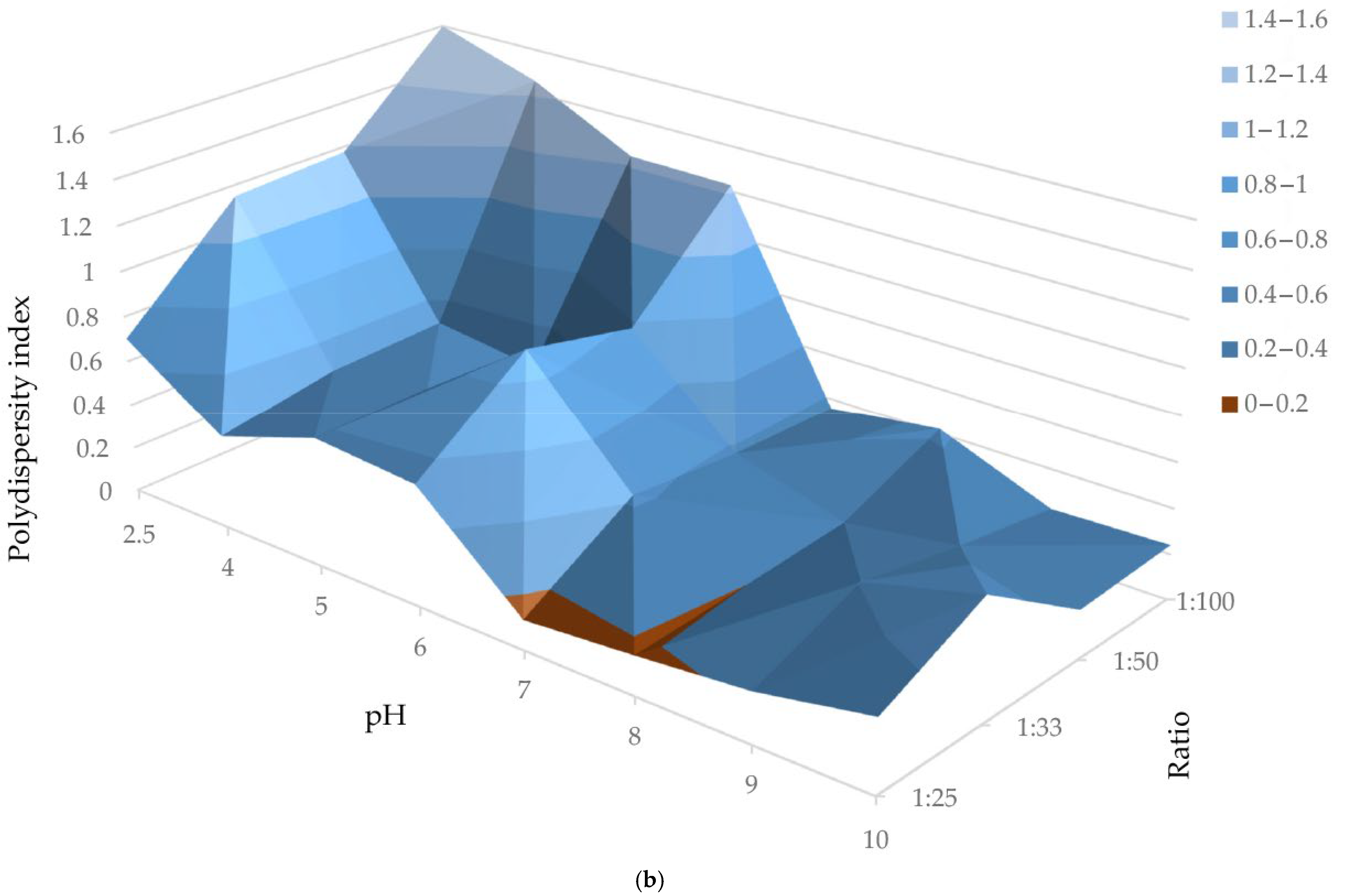

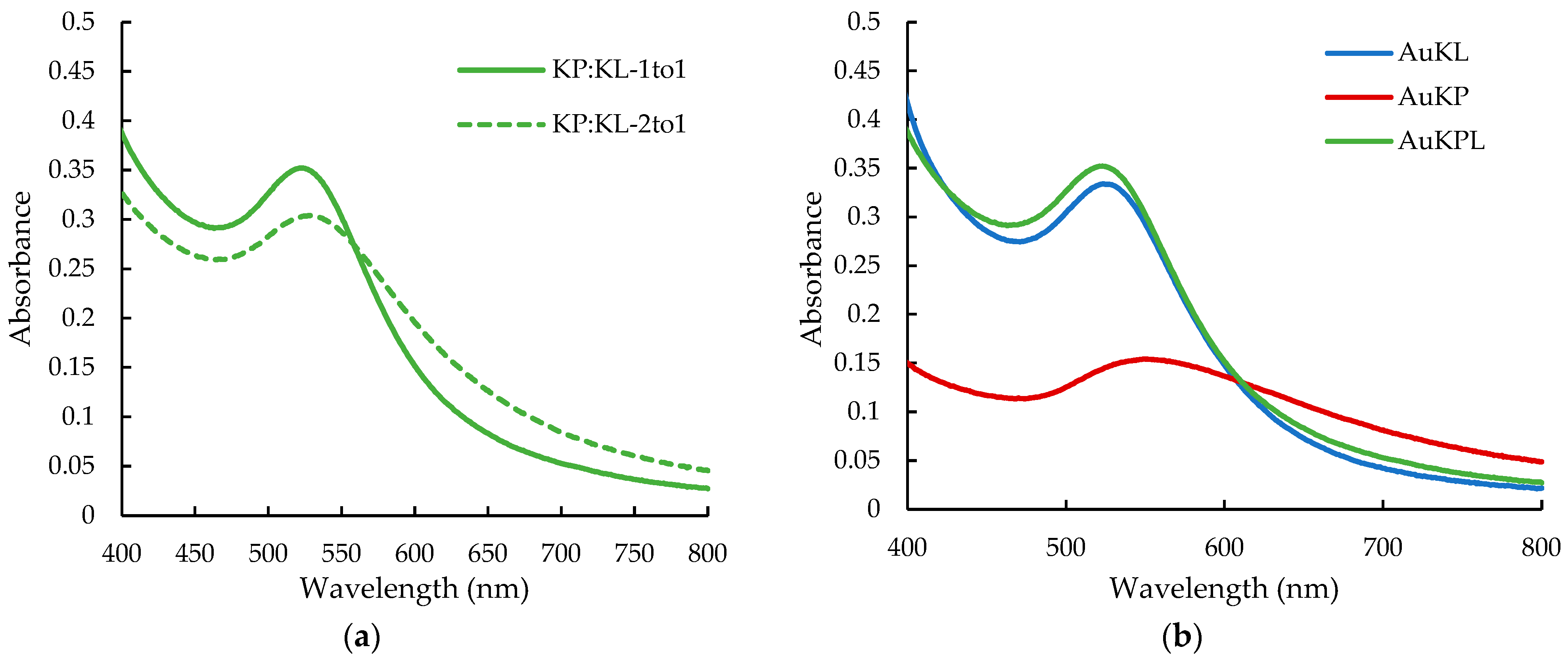

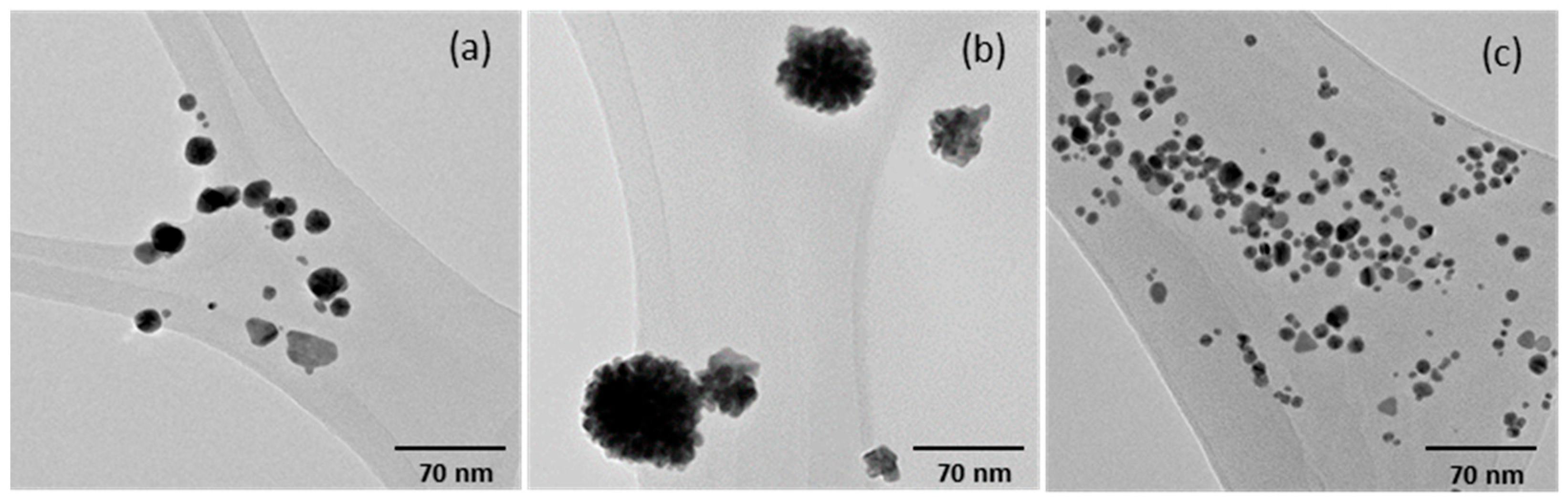

3.1. Optimization and Characterization of AuNPs

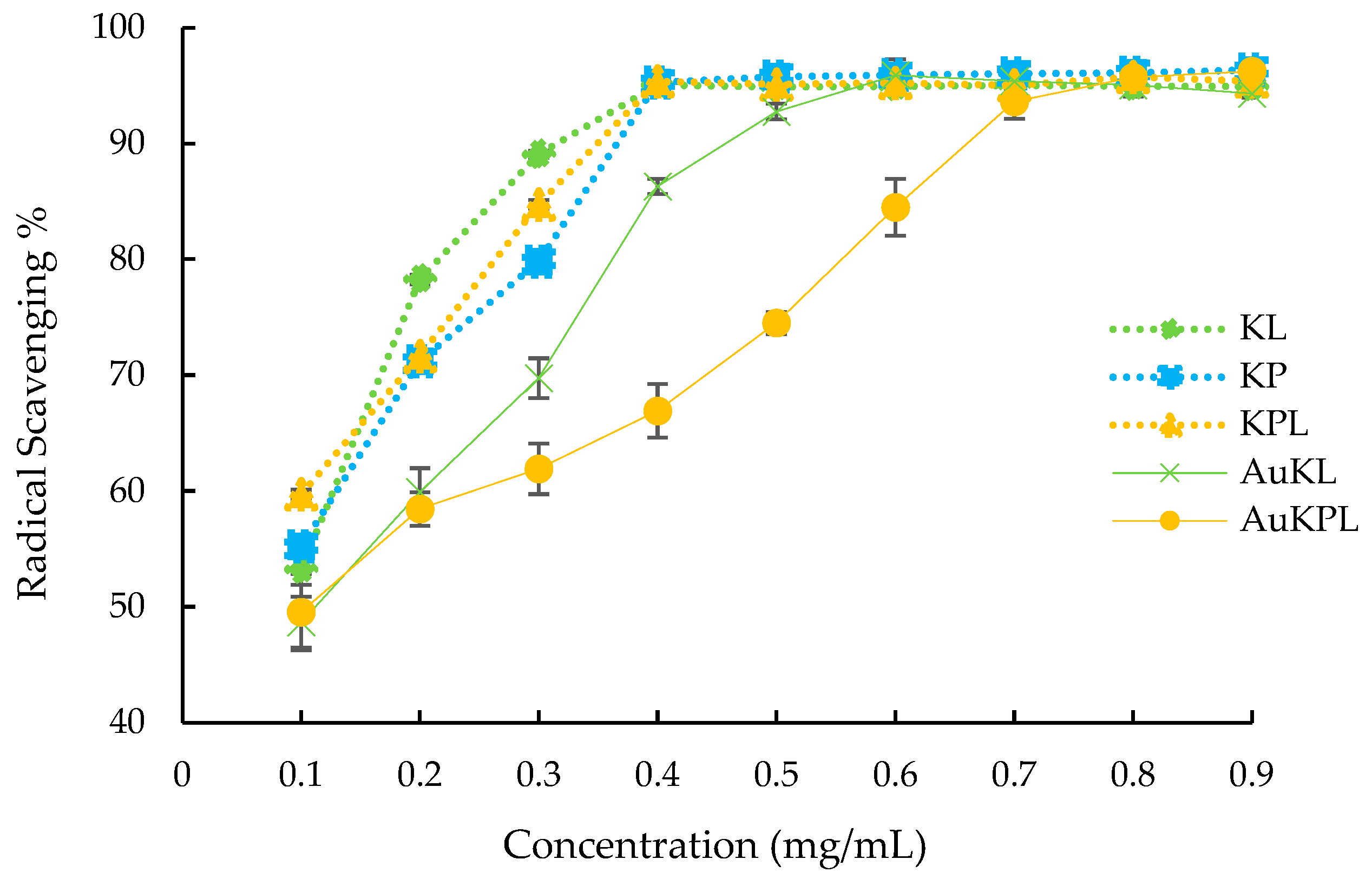

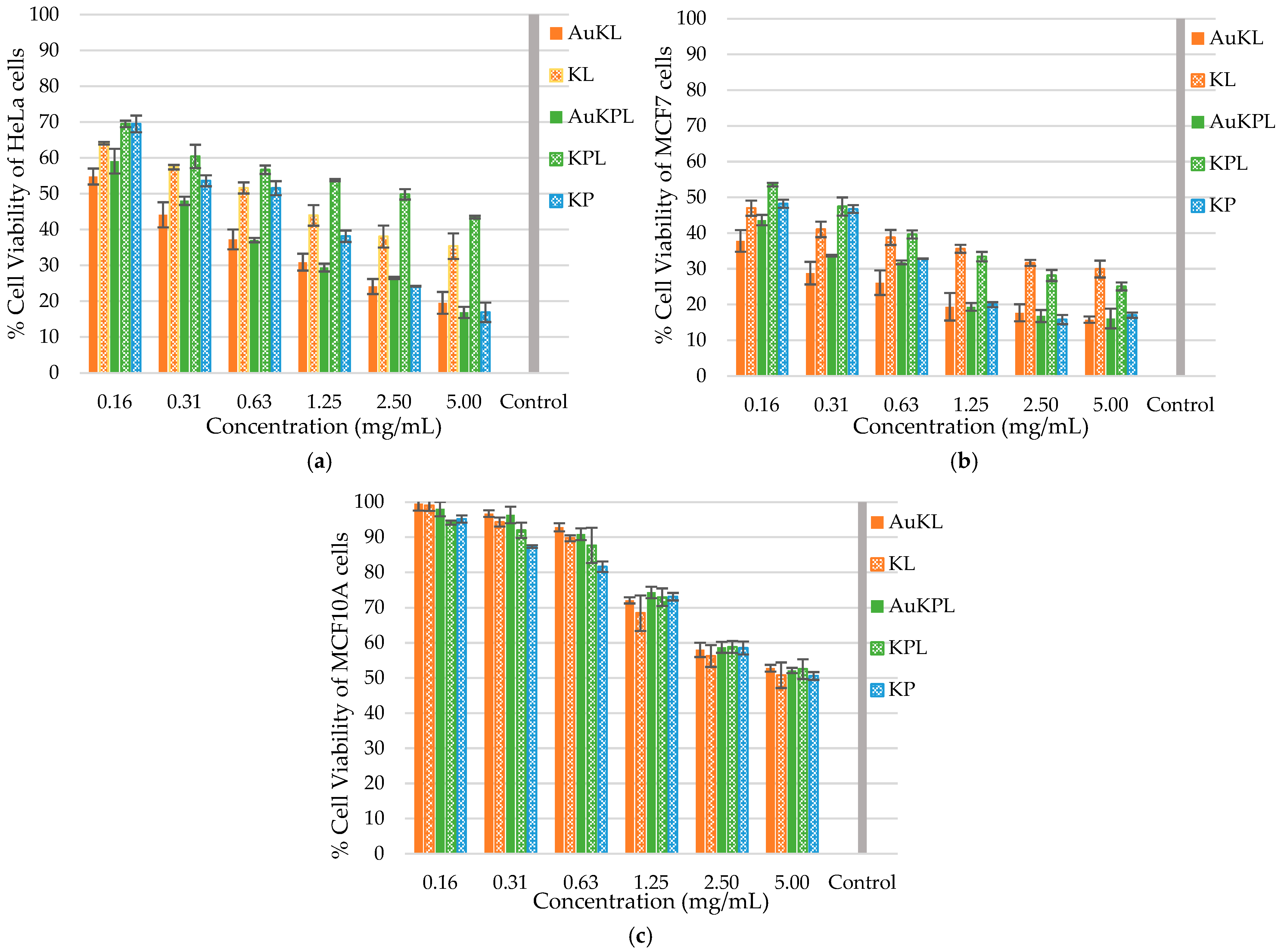

3.2. Biological Activity of AuNPs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A549 | Human lung adenocarcinoma |

| Ag | Silver |

| AgKL | Silver nanoparticles synthesized with leaf extract |

| AgKP | Silver nanoparticles synthesized with fruit extract |

| AgKPL | Silver nanoparticles synthesized with leaf and fruit extract mixture |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| Au | Gold |

| Au3+ | Metallic gold ions |

| AuKL | Gold nanoparticles synthesized with leaf extract |

| AuKP | Gold nanoparticles synthesized with fruit extract |

| AuKPL | Gold nanoparticles synthesized with leaf and fruit extract mixture |

| AuNP | Gold nanoparticles |

| CDU | Charles Darwin University |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DPPH | 2,2 diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GA-1000 | Gentamicin-amphotericin |

| HAuCl4 | Chloroauric acid |

| HeLa | Human cervical carcinoma |

| HepG2 | Human liver cancer cell line |

| HPW | High-purity water |

| KL | Leaf extract |

| KP | Fruit extract |

| KPL | Leaf and fruit extract mixture |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy |

| MCF7 | Breast cancer cell line |

| MCF10A | Normal mammalian breast cell line |

| MEBM | Mammary epithelial cell growth basal medium |

| MEM | Minimum Eagle’s medium |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| NSW | New South Wales |

| NT | Northern Territory |

| OD | Optical density |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| Qld | Queensland |

| QUT | Queensland University of Technology |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| UPLC-MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| USA | United States of America |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| UV-vis | Visible ultraviolet |

References

- Habeeb Rahuman, H.B.; Dhandapani, R.; Narayanan, S.; Palanivel, V.; Paramasivam, R.; Subbarayalu, R.; Thangavelu, S.; Muthupandian, S. Medicinal plants mediated the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 16, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, A.; Dawood, A.; Rida; Saira, F.; Malik, A.; Alkholief, M.; Ahmad, H.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Bazighifan, O. Enhancing catalytic activity of gold nanoparticles in a standard redox reaction by investigating the impact of AuNPs size, temperature and reductant concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Panda, P.K.; Pramanik, N.; Verma, S.K.; Mallick, M.A. Molecular aspect of phytofabrication of gold nanoparticle from Andrographis peniculata photosystem II and their in vivo biological effect on embryonic zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 11, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; He, C.; Kron, S.J.; Lin, W. Nanoparticle formulations of cisplatin for cancer therapy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 8, 776–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, H.K.; Dasgupta, A.K.; Sarkar, S.; Biswas, I.; Chattopadhyay, A. Dual role of nanoparticles as drug carrier and drug. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2011, 2, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Donati, S.; Fontana, L.; Porcaro, F.; Battocchio, C.; Proietti, E.; Venditti, I.; Bracci, L.; Fratoddi, I. Negatively charged gold nanoparticles as a dexamethasone carrier: Stability in biological media and bioactivity assessment in vitro. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 99016–99022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Sreedhar, B.; Banerjee, R. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated delivery of nano gold–with aferin conjugates for reversal of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tumor regression. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 2529–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Li, J.; Bo, L.; Mehta, R.; Ashby, C.R.; Wang, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, Z.-S. Nanotechnology-based delivery systems to overcome drug resistance in cancer. Med. Rev. 2024, 4, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faid, A.H.; Shouman, S.A.; Badr, Y.A.; Sharaky, M. Enhanced cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin conjugated gold nanoparticles on breast cancer model. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, Z.R.; Marín, M.J.; Russell, D.A.; Searcey, M. Active targeting of gold nanoparticles as cancer therapeutics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8774–8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, E. Gold Nanoparticles as Colorimetric Sensors for the Detection of DNA Bases and Related Compounds. Molecules 2020, 25, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwis, W.H.S.; Murthy, V.; Wang, H.; Khandanlou, R.; Mandal, P.K. Green synthesis of Terminalia ferdinandiana Exell-mediated silver nanoparticles and evaluation of antibacterial performance. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Kumar, V. A review on biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles, characterization, and its applications. Resour.-Effic. Technol. 2017, 3, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmad, M.; Swami, B.L.; Ikram, S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: A green expertise. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseingholian, A.; Gohari, S.D.; Feirahi, F.; Moammeri, F.; Mesbahian, G.; Moghaddam, Z.S.; Ren, Q. Recent advances in green synthesized nanoparticles: From production to application. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 24, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, K.S.; Husen, A. Recent advances in plant-mediated engineered gold nanoparticles and their application in biological system. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 40, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, A.K.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J.; Park, Y. Green Synthetic Nanoarchitectonics of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles Prepared Using Quercetin and Their Cytotoxicity and Catalytic Applications. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 2781–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, K.; Santhanalakshmi, J.; Viswanathan, B.; Johnpaul, M.; Srinivasan, K. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Citrus sinensis Peel Extract and Its Antibacterial Activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 79, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barai, A.C.; Paul, K.; Dey, A.; Manna, S.; Roy, S.; Bag, B.G.; Mukhopadhyay, C. Green synthesis of Nerium oleander-conjugated gold nanoparticles and study of its in vitro anticancer activity on MCF-7 cell lines and catalytic activity. Nano Converg. 2018, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Z.; Saleem, R.; Khan, R.R.M.; Liaqat, M.; Pervaiz, M.; Saeed, Z.; Muhammad, G.; Amin, M.; Rasheed, S. Green synthesis, properties, and biomedical potential of gold nanoparticles: A comprehensive review. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 59, 103271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajani, A.A.; Bordbar, A.-K.; Zarkesh Esfahani, S.H.; Razmjou, A. Gold nanoparticles as potent anticancer agent: Green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro study. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 63973–63983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Radadi, N.S. Green Biosynthesis of Flaxseed Gold Nanoparticles (Au-NPs) as Potent Anti-cancer Agent Against Breast Cancer Cells. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandanlou, R.; Murthy, V.; Saranath, D.; Damani, H. Synthesis and characterization of gold-conjugated Backhousia citriodora nanoparticles and their anticancer activity against MCF-7 breast and HepG2 liver cancer cell lines. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 3106–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandanlou, R.; Murthy, V.; Wang, H. Gold nanoparticle-assisted enhancement in bioactive properties of Australian native plant extracts, Tasmannia lanceolata and Backhousia citriodora. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 112, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S. Anticancer activity of eco-friendly gold nanoparticles against lung and liver cancer cells. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2016, 14, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.; Wurm, P.; Vemuri, R.; Brady, C.; Sultanbawa, Y. Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) as a Sustainable Indigenous Agribusiness. Econ. Bot. 2019, 74, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prema, P.; Boobalan, T.; Arun, A.; Rameshkumar, K.; Suresh Babu, R.; Veeramanikandan, V.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Balaji, P. Green tea extract mediated biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles with potent anti-proliferative effect against PC-3 human prostate cancer cells. Mater. Lett. 2022, 306, 130882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Netzel, M.E.; Tinggi, U.; Osborne, S.A.; Fletcher, M.T.; Sultanbawa, Y. Antioxidant rich extracts of Terminalia ferdinandiana inhibit the growth of foodborne bacteria. Foods 2019, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I.E.; Mohanty, S. Evaluation of the antibacterial activity and toxicity of Terminalia ferdinandia fruit extracts. Pharmacogn. J. 2011, 3, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, I.; Zabaras, D.; Dunstan, M.; Aguas, P. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic compounds in commercially grown native Australian fruits. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.; Sirdaarta, J.; Matthews, B.; Cock, I. Tannin components and inhibitory activity of Kakadu plum leaf extracts against microbial triggers of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Pharmacogn. J. 2014, 7, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, I.H.; Alsherbiny, M.A.; Chang, D.; Li, C.G.; Bhuyan, D.J. Antiproliferative effects of Australian native plums against the MCF7 breast adenocarcinoma cells and UPLC-qTOF-IM-MS-driven identification of key metabolites. Food Biosci. 2023, 54, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mashud, M.A.; Moinuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Ahmed, S.; Ahsan, G.; Reza, A.; Anwar Ratul, R.B.; Uddin, M.H.; Momin, M.A.; Hena Mostofa Jamal, M.A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Cinnamomum tamala (Tejpata) leaf and their potential application to control multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from hospital drainage water. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saki, E.; Murthy, V.; Khandanlou, R.; Wang, H.; Wapling, J.; Weir, R. Optimisation of Calophyllum inophyllum seed oil nanoemulsion as a potential wound healing agent. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Shape and size dependence of radiative, non-radiative and photothermal properties of gold nanocrystals. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2000, 19, 409–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, S.K.; Banala, R.R.; Mukherjee, S.; Uppula, P.; Gpv, S.; AV, G.R. Novel biosynthesized gold nanoparticles as anti-cancer agents against breast cancer: Synthesis, biological evaluation, molecular modelling studies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, X.J.; Park, H.R.; Dhandapani, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.J. Biologically synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Cirsium japonicum var. maackii extract and the study of anti-cancer properties on AGS gastric cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5809–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdaarta, J.; Matthews, B.; White, A.; Cock, I.E. GC-MS and LC-MS analysis of Kakadu plum fruit extracts displaying inhibitory activity against microbial triggers of multiple sclerosis. Pharmacogn. Commun. 2015, 5, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdaarta, J. Phytochemical study and anticancer potential of high antioxidant Australian native plants. Ph.D. Thesis, Griffith University, Brisbane City, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sirdaarta, J.; Matthews, B.; Cock, I.E. Kakadu plum fruit extracts inhibit growth of the bacterial triggers of rheumatoid arthritis: Identification of stilbene and tannin components. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Yu, X.; Law, W.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, R.; Dinh, X.-Q.; Ho, H.-P.; Yong, K.-T. Size dependence of Au NP-enhanced surface plasmon resonance based on differential phase measurement. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 176, 1128–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, C.; Mei, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L. Fabrication of genistein-loaded biodegradable TPGS-b-PCL nanoparticles for improved therapeutic effects in cervical cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okitsu, K.; Sharyo, K.; Nishimura, R. One-pot synthesis of gold nanorods by ultrasonic irradiation: The effect of pH on the shape of the gold nanorods and nanoparticles. Langmuir 2009, 25, 7786–7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekov, R.; Georgiev, P.; Simeonova, S.; Balashev, K. Quantifying the Blue Shift in the Light Absorption of Small Gold Nanoparticles. Comptes Rendus l’Académie Bulg. Sci. Sci. Mathématiques Nat. 2017, 70, 1237. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, S.S.; Rai, A.; Ahmad, A.; Sastry, M. Rapid synthesis of Au, Ag, and bimetallic Au core–Ag shell nanoparticles using Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf broth. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2004, 275, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.M.H.; Ismail, E.H.; El-Magdoub, F. Biosynthesis of Au nanoparticles using olive leaf extract: 1st Nano Updates. Arab. J. Chem. 2012, 5, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oćwieja, M.; Morga, M. Electrokinetic properties of cysteine-stabilized silver nanoparticles dispersed in suspensions and deposited on solid surfaces in the form of monolayers. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 297, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figat, A.M.; Bartosewicz, B.; Liszewska, M.; Budner, B.; Norek, M.; Jankiewicz, B.J. α-Amino Acids as Reducing and Capping Agents in Gold Nanoparticles Synthesis Using the Turkevich Method. Langmuir 2023, 39, 8646–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, N.C.; Shin, K. Synthesis of L-phenylalanine stabilized gold nanoparticles and their thermal stability. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006, 6, 3512–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Zare, D.; Farhangi, A.; Mehrabi, M.R.; Norouzian, D.; Tangestaninejad, S.; Moghadam, M.; Bararpour, N. Synthesis and Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles by Tryptophane. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2009, 6, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, B.; Ralević, U.; Petrović, S.; Leskovac, A.; Vasić-Anićijević, D.; Marković, M.; Vasić, V. Green synthesis and characterization of nontoxic L-methionine capped silver and gold nanoparticles. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 204, 110958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Qi, L.; Dong, P.; Qiao, J.; Hou, J.; Nie, Z.; Ma, H. Facile one-pot synthesis of L-proline-stabilized fluorescent gold nanoclusters and its application as sensing probes for serum iron. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 49, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.W. Amino acid mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and preparation of antimicrobial agar/silver nanoparticles composite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 130, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumi, G.; Demissie, T.B.; Eswaramoorthy, R.; Bogale, R.F.; Kenasa, G.; Desalegn, T. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Functionalized with Histidine and Phenylalanine Amino Acids for Potential Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24371–24386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.M.; Mendes Filho, A.d.A.; dos Santos, D.J.; dos Santos, L.T. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using modified lignin as a reducing agent. Next Mater. 2024, 2, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Mehata, M.S. Medicinal Plant Leaf Extract and Pure Flavonoid Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and their Enhanced Antibacterial Property. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathishkumar, P.; Gu, F.L.; Zhan, Q.; Palvannan, T.; Mohd Yusoff, A.R. Flavonoids mediated ‘Green’ nanomaterials: A novel nanomedicine system to treat various diseases—Current trends and future perspective. Mater. Lett. 2018, 210, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibała, A.; Żeliszewska, P.; Gosiewski, T.; Krawczyk, A.; Duraczyńska, D.; Szaleniec, J.; Szaleniec, M.; Oćwieja, M. Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Silver Nanoparticles-Effect of a Surface-Stabilizing Agent. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaby, S.N.; Yu, S.M.; Fath, K.R.; Tsiola, A.; Khalpari, O.; Banerjee, I.A. Ellagic acid promoted biomimetic synthesis of shape-controlled silver nanochains. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 225605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.-P.; Ma, B.-Y.; Wei, X.-W.; Qian, Z.-Y. The in vitro and in vivo toxicity of gold nanoparticles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzel, M.; Netzel, G.; Tian, Q.; Schwartz, S.; Konczak, I. Native Australian fruits—A novel source of antioxidants for food. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, I.; Maillot, F.; Dalar, A. Phytochemical divergence in 45 accessions of Terminalia ferdinandiana (Kakadu plum). Food Chem. 2014, 151, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Konczak, I.; Ramzan, I.; Zabaras, D.; Sze, D.M.Y. Potential Antioxidant, Antiinflammatory, and Proapoptotic Anticancer Activities of Kakadu Plum and Illawarra Plum Polyphenolic Fractions. Nutr. Cancer 2011, 63, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom, J.; Rayan, P.; Courtney, R.; McDonnell, P.A.; Cock, I.E. Terminalia ferdinandiana Exell. Kino Extracts have Anti-Giardial Activity and Inhibit CaCO2 and HeLa Cancer Cell Proliferation. Pharmacogn. Commun. 2018, 8, 60-65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhania, Z.M.; Nahar, J.; Ahn, J.C.; Yang, D.U.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, D.W.; Kong, B.M.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Rupa, E.J.; Akter, R.; et al. Terminalia ferdinandiana (Kakadu Plum)-Mediated Bio-Synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles for Enhancement of Anti-Lung Cancer and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahle, K.W.; Brown, I.; Rotondo, D.; Heys, S.D. Plant phenolics in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 698, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Gandhi, A.; Fimognari, C.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bishayee, A. Alkaloids for cancer prevention and therapy: Current progress and future perspectives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinsan, K.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Therapeutic role of alkaloids and alkaloid derivatives in cancer management. Molecules 2023, 28, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukharta, M.; Jalbert, G.; Castonguay, A. Biodistribution of ellagic acid and dose-related inhibition of lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Nutr. Cancer 1992, 18, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Yang, D.; He, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, G. Phenolic compound ellagic acid inhibits mitochondrial respiration and tumor growth in lung cancer. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 6332–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Seresht, H.; Cheshomi, H.; Falanji, F.; Movahedi-Motlagh, F.; Hashemian, M.; Mireskandari, E. Cytotoxic activity of caffeic acid and gallic acid against MCF-7 human breast cancer cells: An in silico and in vitro study. Avicenna J. Phytomedicine 2019, 9, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Verma, R. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids in the Management of Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2024, 26, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavsan, Z.; Kayali, H.A. Flavonoids showed anticancer effects on the ovarian cancer cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species, apoptosis, cell cycle and invasion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Jakstas, V.; Savickas, A.; Bernatoniene, J. Flavonoids as Anticancer Agentvs. Nutrients 2020, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Neuss, S.; Leifert, A.; Fischler, M.; Wen, F.; Simon, U.; Schmid, G.; Brandau, W.; Jahnen-Dechent, W. Size-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Gold Nanoparticles. Small 2007, 3, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Rong, H.; Lu, W.; Jiang, L. Effects of aggregation and the surface properties of gold nanoparticles on cytotoxicity and cell growth. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2012, 8, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liao, J.; Shao, X.; Li, Q.; Lin, Y. The Effect of shape on Cellular Uptake of Gold Nanoparticles in the forms of Stars, Rods, and Triangles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; Wahab, R. Size-dependent cytotoxic and molecular study of the use of gold nanoparticles against liver cancer cells. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunandan, D.; Ravishankar, B.; Sharanbasava, G.; Mahesh, D.B.; Harsoor, V.; Yalagatti, M.S.; Bhagawanraju, M.; Venkataraman, A. Anti-cancer studies of noble metal nanoparticles synthesized using different plant extracts. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2011, 2, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, M.P.; Ngabire, D.; Thi, H.H.P.; Kim, M.-D.; Kim, G.-D. Eco-friendly Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Cytotoxic Activity on Cancer Cells. J. Clust. Sci. 2017, 28, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.-M.; Lee, Y.-H.; Liang, R.-Y.; Roam, G.-D.; Zeng, Z.-M.; Tu, H.-F.; Wang, S.-K.; Chueh, P.J. Extensive evaluations of the cytotoxic effects of gold nanoparticles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 4960–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AuNPs | Zeta Potential (mV) | PDI | Hydrodynamic Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AuKL s | −80.1 | 0.17 | 21.1 |

| AuKPs | −71.8 | 0.70 | 144 |

| AuKPLs | −73.3 | 0.37 | 28.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alwis, W.H.S.; Murthy, V.; Wang, H.; Khandanlou, R.; Weir, R. Biofabrication of Terminalia ferdinandiana-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles and Their Anticancer Properties. Life 2025, 15, 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121829

Alwis WHS, Murthy V, Wang H, Khandanlou R, Weir R. Biofabrication of Terminalia ferdinandiana-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles and Their Anticancer Properties. Life. 2025; 15(12):1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121829

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlwis, Weerakkodige Hansi Sachintha, Vinuthaa Murthy, Hao Wang, Roshanak Khandanlou, and Richard Weir. 2025. "Biofabrication of Terminalia ferdinandiana-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles and Their Anticancer Properties" Life 15, no. 12: 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121829

APA StyleAlwis, W. H. S., Murthy, V., Wang, H., Khandanlou, R., & Weir, R. (2025). Biofabrication of Terminalia ferdinandiana-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles and Their Anticancer Properties. Life, 15(12), 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121829