Lingyuanfructus: The First Fossil Angiosperm with Naked Seeds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

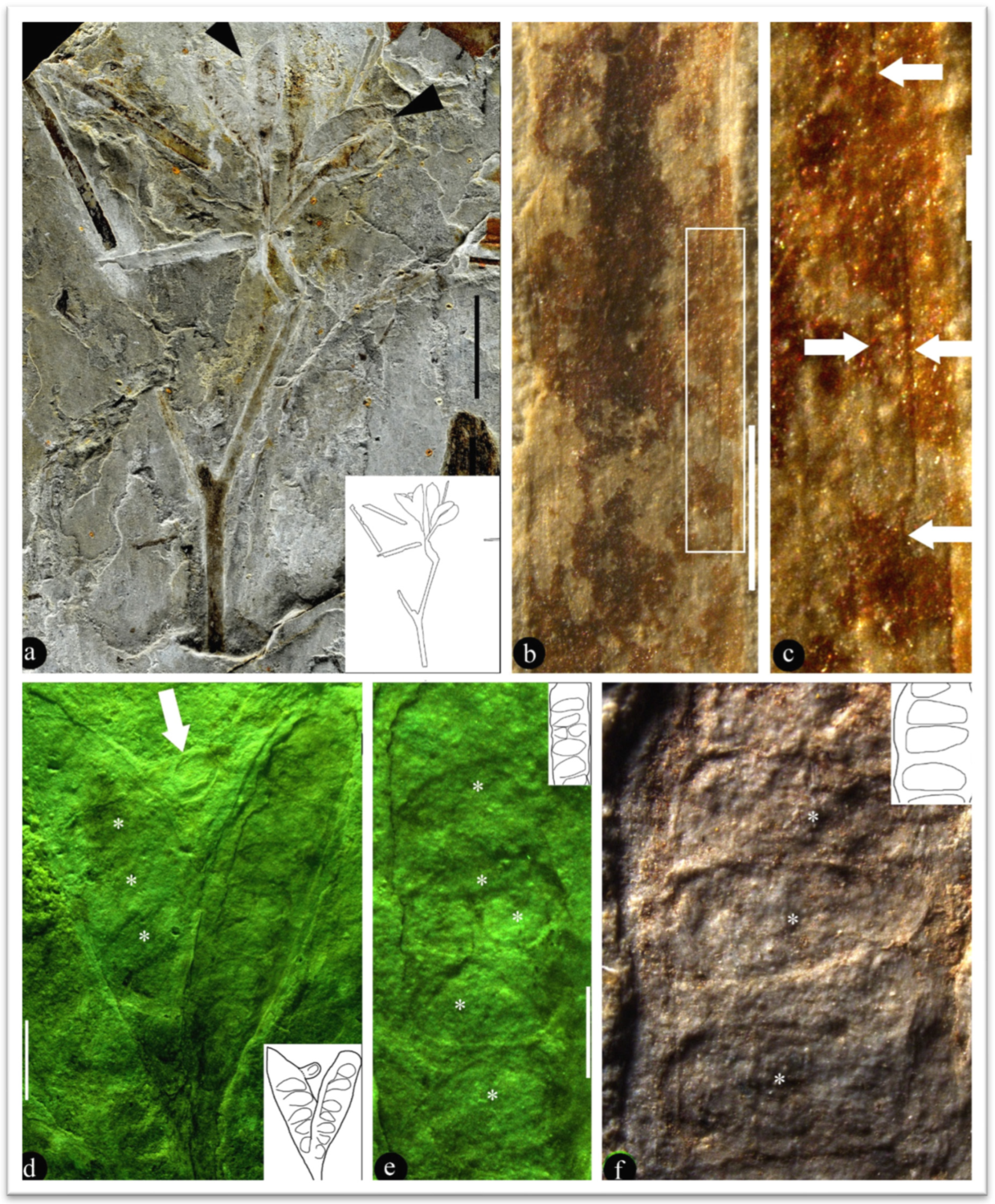

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- Duan, S. The oldest angiosperm—A tricarpous female reproductive fossil from western Liaoning Province, NE China. Sci. China D 1998, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Dilcher, D.L.; Zheng, S.; Zhou, Z. In search of the first flower: A Jurassic angiosperm, Archaefructus, from Northeast China. Science 1998, 282, 1692–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, G.; Ji, Q.; Dilcher, D.L.; Zheng, S.; Nixon, K.C.; Wang, X. Archaefructaceae, a new basal angiosperm family. Science 2002, 296, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, Q.; Friis, E.M. Sinocarpus decussatus gen. et sp. nov., a new angiosperm with basally syncarpous fruits from the Yixian Formation of Northeast China. Plant Syst. Evol. 2003, 241, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Q.; Friis, E.M. Angiosperm leaves associated with Sinocarpus infructescences from the Yixian Formation (Mid-Early Cretaceous) of NE China. Plant Syst. Evol. 2006, 262, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. The Dawn Angiosperms; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Diez, J.B.; Pole, M.; Garcia-Avila, M.; Liu, Z.-J.; Chu, H.; Hou, Y.; Yin, P.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Du, K.; et al. An unexpected noncarpellate epigynous flower from the Jurassic of China. eLife 2018, 7, e38827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, D.D.; Remizowa, M.V.; El, E.S.; Rudall, P.J.; Bateman, R.M. Supposed Jurassic angiosperms lack pentamery, an important angiosperm-specific feature. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiro, M.; Doyle, J.A.; Hilton, J. How deep is the conflict between molecular and fossil evidence on the age of angiosperms? New Phytol. 2019, 223, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.M. Hunting the snark: The flawed search for mythical Jurassic angiosperms. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Pedersen, K.R.; von Balthazar, M.; Grimm, G.W.; Crane, P.R. Monetianthus mirus gen. et sp. nov., a Nymphaealean flower from the Early Cretaceous of Portugal. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 170, 1086–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Criterion is a touchstone in study of early angiosperms. Open J. Plant Sci. 2021, 6, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Pedersen, K.R.; Crane, P.R. Fossil evidence of water lilies (Nymphaeales) in the Early Cretaceous. Nature 2001, 410, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelord, D. A theory of angiosperm evolution. Evolution 1952, 6, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, G.L.J. Variation and Evolution in Plants; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, G.L. Why are there so many species of flowering plants? Bioscience 1981, 31, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, G.L. Seeds, seedlings, and the origin of angiosperms. In Origin and Early Evolution of Angiosperms; Beck, C.B., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Arber, E.A.N.; Parkin, J. On the origin of angiosperms. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. Bot. 1907, 38, 29–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeuse, A.D.J. Sixty-five years of theories of the multiaxial flower. Acta Biotheory 1972, 21, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, R. The origin of flowers. New Sci. 1964, 22, 494–496. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, R. A new theory of the angiosperm flower: I. The gynoecium. Kew Bull. 1962, 16, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilcher, D.L.; Crane, P.R. Archaeanthus: An early angiosperm from the Cenomanian of the Western Interior of North America. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1984, 71, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canright, J.E. The comparative morphology and relationships of the Magnoliaceae. III. Carpels. Am. J. Bot. 1960, 47, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.-J.; Liu, W.; Liao, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Hu, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y. Stepping out of the shadow of Goethe: For a more scientific plant systematics. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2020, 55, 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Sun, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, X. Unique Jurassic ovaries shed a new light on the nature of carpels. Plants 2024, 13, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. How the ovules get enclosed in magnoliaceous carpels. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X. Floral ontogeny of Illicium lanceolatum (Schisandraceae) and its implications on carpel homology. Phytotaxa 2019, 416, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.; Wang, X. Pre-carpels from the Middle Triassic of Spain. Plants 2022, 11, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, D.J.; Hill, T.A.; Gasser, C.S. Regulation of ovule development. Plant Cell 2004, 16, S32–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.; Kramer, E.M. The evolution of reproductive structures in seed plants: A re-examination based on insights from developmental genetics. New Phytol. 2012, 194, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Crane, P.R.; Herendeen, P.S.; Leslie, A.B.; Ichinnorov, N.; Takahashi, M.; Herrera, F. Diversity and homologies of corystosperm seed-bearing structures from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2019, 17, 997–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.L.; Nemhauser, J.L.; Zambryski, P.C. TOUSLED participates in apical tissue formation during gynoecium development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Buzgo, M.; Soltis Pamela, S.; Soltis Douglas, E. Floral developmental morphology of Amborella trichopoda (Amborellaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2004, 165, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, A. Studies in flower structure: VII. On the gynaeceum of Reseda, with a consideration of paracarpy. Ann. Bot. 1942, 6, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Li, H.; Bowe, M.; Liu, Y.; Taylor, D.W. Early Cretaceous Archaefructus eoflora sp. nov. with bisexual flowers from Beipiao, Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2004, 78, 883–896. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-J.; Wang, X. A novel angiosperm from the Early Cretaceous and its implications on carpel-deriving. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 92, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z.-J.; Wang, X. A novel angiosperm including various parts from the Early Cretaceous sheds new light on flower evolution. Hist. Biol. 2021, 33, 2706–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. A Dichocarpum-like angiosperm from the Early Cretaceous of China. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 90, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Friis, E.M.; Crane, P.R.; Pedersen, K.R. The Early Flowers and Angiosperm Evolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S.; Yang, F.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, Q. Standard Sections of Tuchengzi Stage and Yixian Stage and Their Stratigraphy, Palaeontology and Tectonic-Volcanic Actions; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y. 40Ar/39Ar dating of the lower Yixian Fm, Liaoning Province, northeastern China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1998, 43, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.-J.; Zheng, S.-L.; Yang, F.-L.; Li, Z.-T.; Zheng, Y.-J. Stratigraphic sequence of the Yixian Formation of Yixian-Beipiao region, Liaoning—A study and establishment of stratotype of the Yixian stage. J. Stratigr. 2003, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-L.; Zhang, L.-J.; Zheng, S.-L.; Ren, D.; Zheng, Y.-J.; Ding, Q.-H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.-T.; Yang, F.-L. The age of the Yixianian stage and the boundary of Jurassic-Cretaceous—The establishment and study of stratotype of the Yixianian stage. Geol. Rev. 2005, 51, 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Ren, D.; Wang, Y. First discovery of angiospermous pollen from Yixian Formation. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2000, 74, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, D.-H.; Sun, C.-L.; Sun, Y.-W.; Zhang, L.-D.; Peng, Y.-D.; Chen, S.-W. New knowledge on Yixian Formation. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2005, 26, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Li, S.; Jiang, B. New evidence for Cretaceous age of the feathered dinosaurs of Liaoning: Zircon U-Pb SHRIMP dating of the Yixian Formation in Sihetun, northeast China. Cretac. Res. 2007, 28, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rasnitsyn, A.P.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Some hatchet wasps (Hymenoptera, Evaniidae) from the Yixian Formation of western Liaoning, China. Cretac. Res. 2007, 28, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J. Cretaceous stratigraphy of northeast China: Non-marine and marine correlation. Cretac. Res. 2007, 28, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Zhang, H.; Renne, P.R.; Fang, Y. High-precision 40Ar/39Ar age constraints on the basal Lanqi Formation and its implications for the origin of angiosperm plants. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 279, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Ji Sa Lu, J.; You, H.; Yuan, C. On the geological age of Daohugou biota. Geol. Rev. 2005, 51, 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X. On the Lower Cretaceous in Yixian County of Jinzhou City, Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2011, 85, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilcher, D.L.; Sun, G.; Ji, Q.; Li, H. An early infructescence Hyrcantha decussata (comb. nov.) from the Yixian Formation in northeastern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9370–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Q. A preliminary study of the Jehol flora from the western Liaoning. Palaeoworld 1999, 11, 7–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Zheng, S.; Dilcher, D.; Wang, Y.; Mei, S. Early Angiosperms and Their Associated Plants from Western Liaoning, China; Shanghai Technology and Education Press: Shanghai, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Zhou, Z. A new Mesozoic Ginkgo from western Liaoning, China and its evolutionary significance. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2004, 131, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Q.; Wu, S.-Q.; Friis, E.M. Angiosperms. In The Jehol Biota; Chang, M.-M., Chen, P.-J., Wang, Y.-Q., Wang, Y., Miao, D.-S., Eds.; Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2003; pp. 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, X.-T. Reconsiderations on two characters of early angiosperm Archaefructus. Palaeoworld 2012, 21, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, X. Flower buds confirmed in the Early Cretaceous of China. Biology 2024, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, P.B.; Takaso, T. Seed cone structure in conifers in relation to development and pollination: A biological approach. Can. J. Bot. 2002, 80, 1250–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, G. Cordaianthus duquesnensis sp. nov., anatomically preserved ovulate cones from the Upper Pennsylvanian of Ohio. Am. J. Bot. 1982, 69, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. On the origin of outer integument. China Geol. 2022, 5, 777–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. New observation on seed/ovule position in the fruit of Archaeanthus and its systematic implications. China Geol. 2021, 4, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Fu, X.; Liu, Z.-J.; Wang, X. A new angiosperm genus from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation, Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2013, 87, 916–925. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Hou, Y.; Yin, P.; Diez, J.B.; Pole, M.; García-Ávila, M.; Wang, X. Micro-CT results exhibit ovules enclosed in the ovaries of Nanjinganthus. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Diez, J.B.; Pole, M.; García-Ávila, M.; Wang, X. Nanjinganthus is an angiosperm, isn’t it? China Geol. 2020, 3, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, Q. Taiyuanostachya: An abominable angiosperm from the Early Permian of China. J. Biotechnol. Biomed. 2023, 6, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lei, Y.; Fu, Q. Yuzhoua juvenilis: Another angiosperm seen in the Early Permian. Life 2025, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Duan, S.; Geng, B.; Cui, J.; Yang, Y. Schmeissneria: A missing link to angiosperms? BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. Schmeissneria: An angiosperm from the Early Jurassic. J. Syst. Evol. 2010, 48, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (Byng J. W.; Chase, M.W.; Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Fay, M.F.; Judd, W.S.; Mabberley, D.J.; Sennikov, A.N.; Soltis, D.E.; Soltis, P.S.; Stevens, P.F.). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Pedersen, K.R. Canrightia resinifera gen. et sp. nov., a new extinct angiosperm with Retimonocolpites-type pollen from the Early Cretaceous of Portugal: Missing link in the eumagnoliid tree? Grana 2011, 50, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Grimm, G.W.; Mendes, M.M.; Pedersen, K.R. Canrightiopsis, a new Early Cretaceous fossil with Clavatipollenites-type pollen bridge the gap between extinct Canrightia and extant Chloranthaceae. Grana 2015, 54, 184–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Lu, A.-M.; Tang, Y.-C.; Chen, Z.-D.; Li, D.-Z. Synopsis of a new “polyphyletic-polychronic-polytopic” system of the angiosperms. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 2002, 40, 289–322. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-J.; Wang, X. A perfect flower from the Jurassic of China. Hist. Biol. 2016, 28, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X. Lingyuanfructus: The First Fossil Angiosperm with Naked Seeds. Life 2025, 15, 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121827

Wang X. Lingyuanfructus: The First Fossil Angiosperm with Naked Seeds. Life. 2025; 15(12):1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121827

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xin. 2025. "Lingyuanfructus: The First Fossil Angiosperm with Naked Seeds" Life 15, no. 12: 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121827

APA StyleWang, X. (2025). Lingyuanfructus: The First Fossil Angiosperm with Naked Seeds. Life, 15(12), 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121827