Influence of Pigment Composition and Painting Technique on Soiling Removal from Wall Painting Mock-Ups Using an UV Nanosecond Nd:YAG Laser

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. Pigment Tablets

2.2.2. Fresco and Secco Painting Mock-Ups

2.2.3. Artificial Aging of the Paint Mock-Ups

2.3. Laser Application

2.4. Analytical Techniques

- The mineralogical composition of the pigments, calcitic lime putty, coarse and fine silica, marble powder, and soot was analysed using X-ray diffraction (XRD, XPert PRO PANalytical B.V., Almelo, The Netherlands) according to the random-powder method. Analyses were performed using Cu-Kα radiation, a Ni filter, 45 kV voltage, and 40 mA intensity. The exploration range was 3–60° 2θ and the goniometer speed was 0.05° 2θ s−1. The oriented aggregate method was also used to properly identify the presence of phyllosilicates in the GE pigment [46]. The mineral phases were identified using the X’Pert HighScore software (version 4.9.0.27512).

- The elemental composition of the soot and pigments was determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with an Olympus Vanta C Handheld XRF analyser (Hamburg, Germany) in “GeoChem” mode, using 3-beams working at 40, 10, and 50 kV. The total measurement time was 60 s: 20 s for each beam. Element recognition was obtained by means of the suppliers database. The equipment was used to identify chemical elements of atomic number greater than 12. As no specific calibration was applied apart from the default calibration of the equipment, the composition obtained is semi-quantitative.

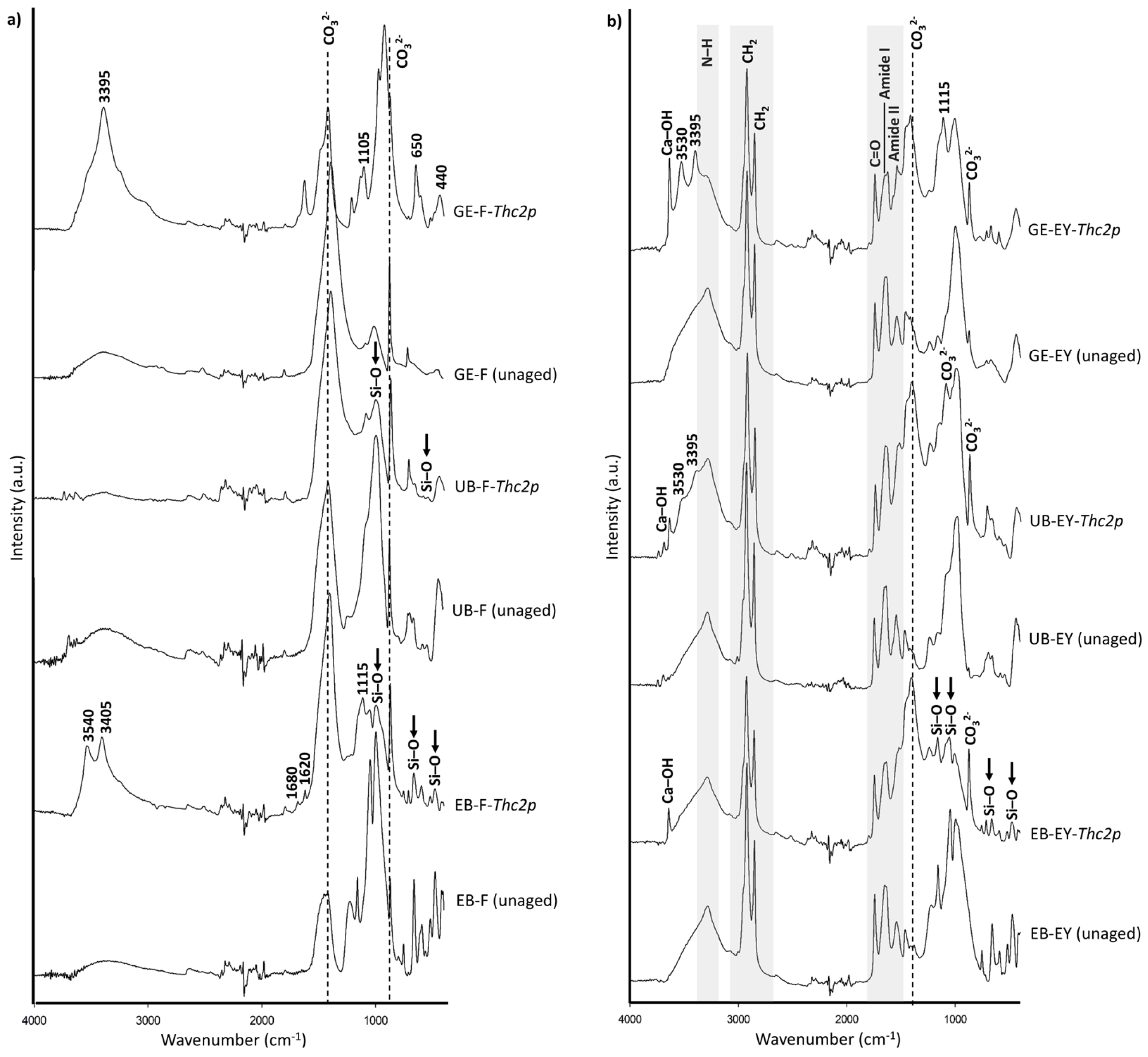

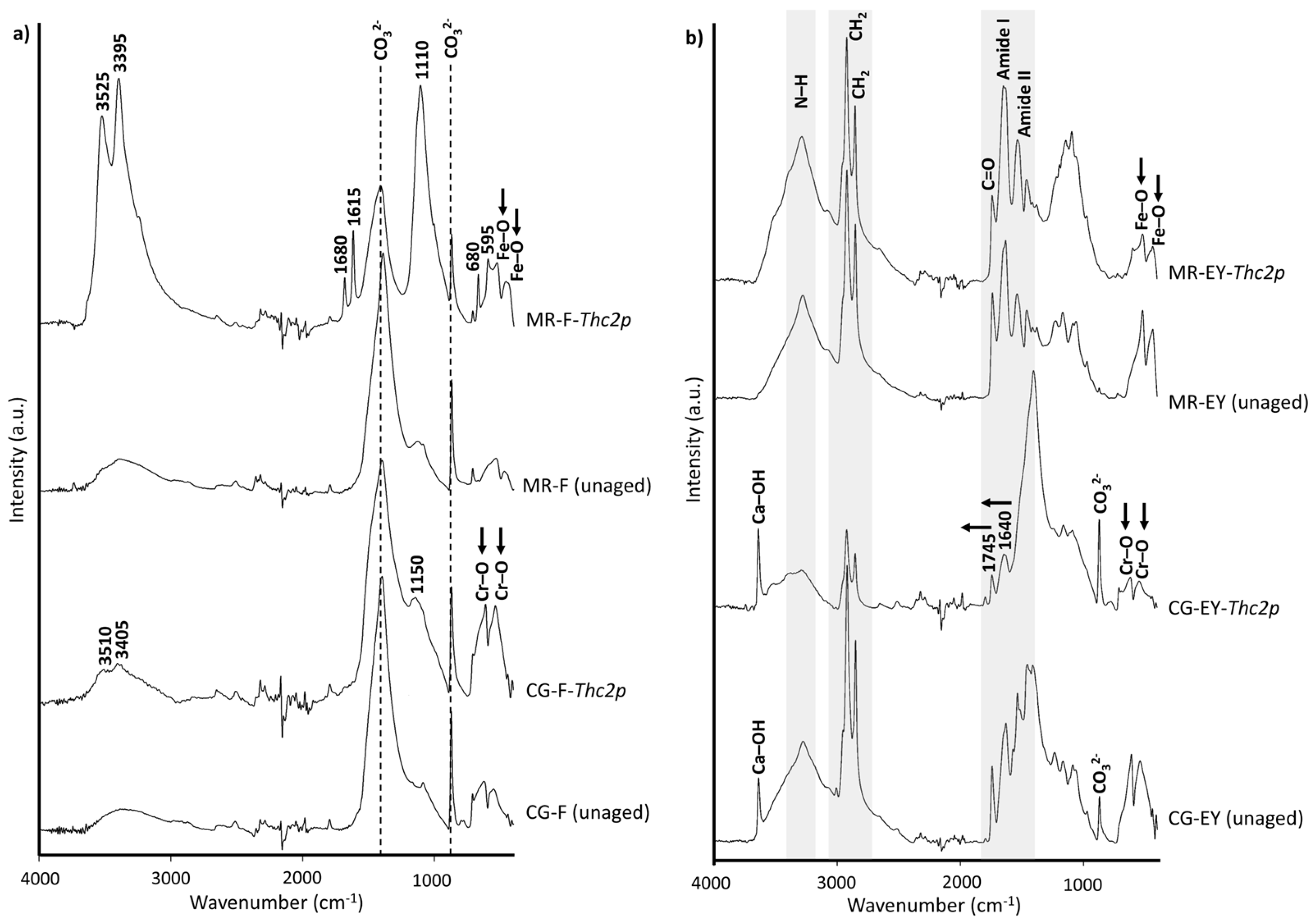

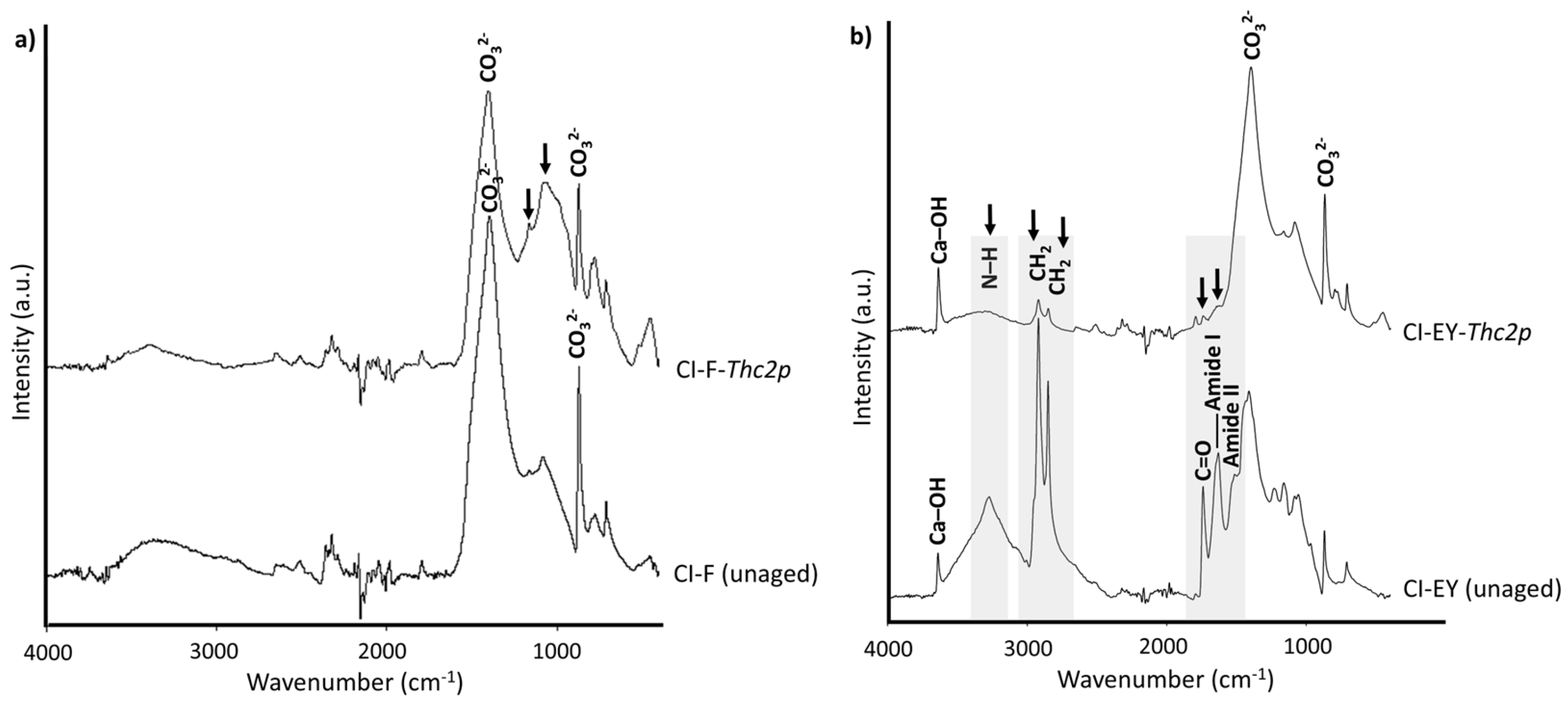

- The molecular composition of the pigments and soot was obtained by Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier–Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), using a Thermo Nicolet 6700 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at a 2 cm−1 resolution over 32 scans in the mid infrared spectral region (400–4000 cm−1).

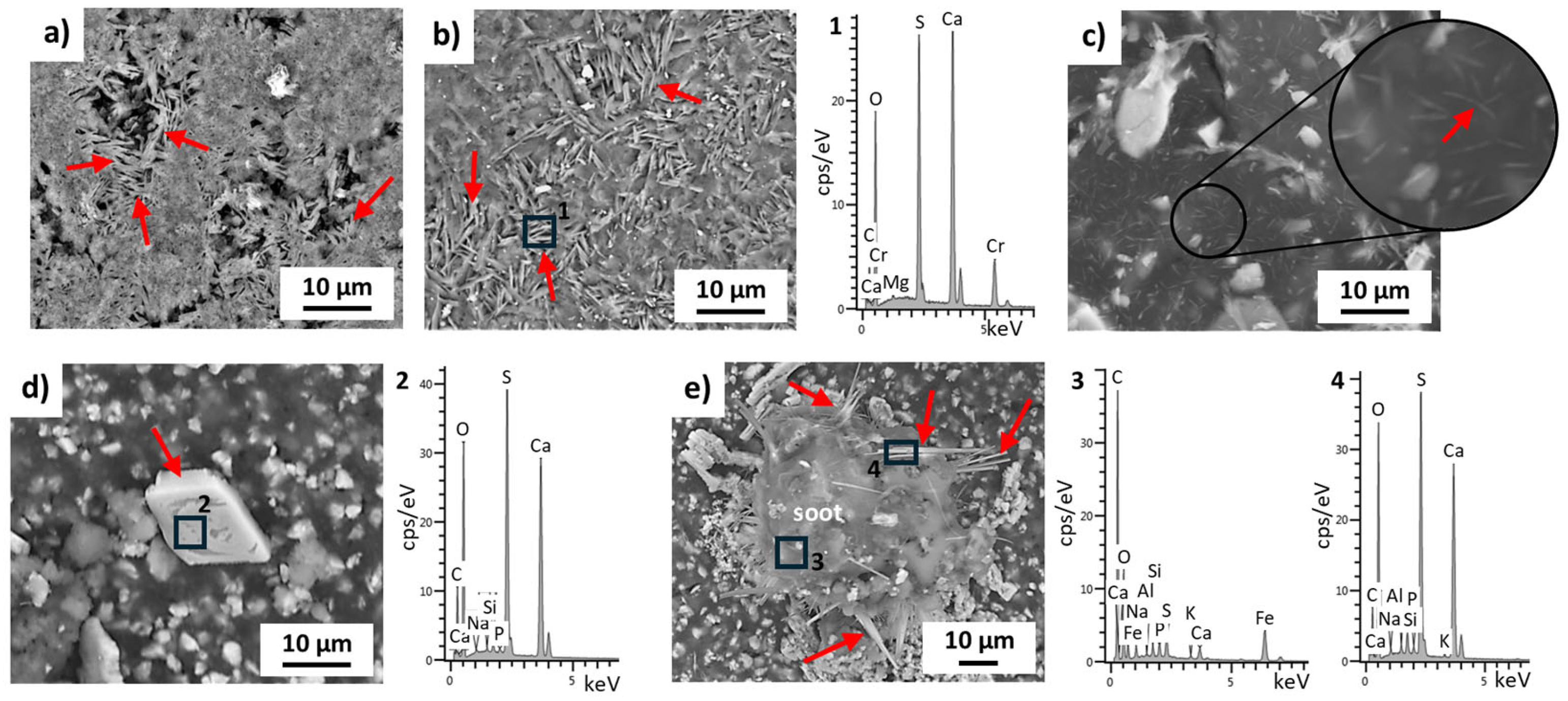

- Soot was studied using a FEI Quanta 200 environmental scanning electron microscopy (Hillsboro, OR, USA) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) in both secondary (SE)- and backscattered electron (BSE)-detection modes. Observation conditions included a working distance of ~10 mm, accelerating potential of 20 kV, and specimen current of ~60 mA.

- The specimen’s morphology was examined using a Nikon SMZ 1000 stereomicroscope (Melville, NY, USA).

- The colour was characterized by colour spectrophotometry using CIELAB and CIELCH colour spaces [47], measuring L* (lightness), a* and b* (colour coordinates), C*ab (chroma), and h (hue) by means of a Minolta CM-700d spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan). L* represents lightness, varying from 0 (black) to 100 (white). The other two parameters are chromaticity coordinates: a* goes from red to green (where +a* is red and -a* is green) and b* from yellow to blue (+b* is yellow and -b* is blue). C*ab is calculated according to the following formula: C*ab = (a2 + b2)1/2 and h is calculated by means of the expression h = tan [1 − (a*/b*)].The measurements were made in the specular component excluded (SCE) mode, for a spot diameter of 8 mm, using illuminant D65 at an observer angle of 10°. A total of five measurements were made on unaged paint mock-ups and artificially aged mock-ups (before and after radiation). ΔL*, Δa*, Δb*, ΔC*ab, and ΔH* and colour difference (ΔE*ab = [ ΔL*2 + Δa*2 + Δb*2]1/2) were calculated between the non-irradiated and the irradiated areas following [48].

- The molecular composition was obtained by ATR-FTIR, using the same equipment and conditions described above.

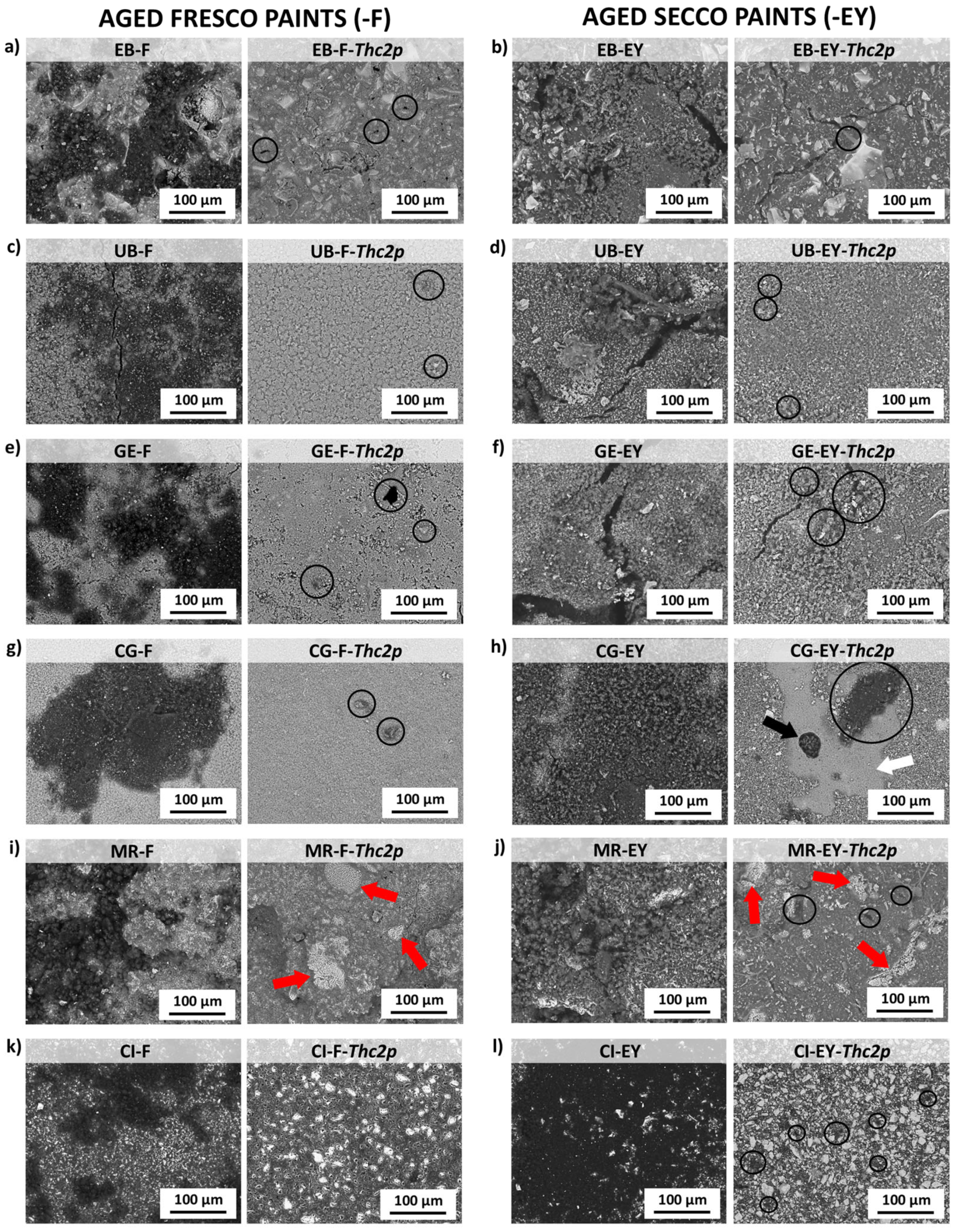

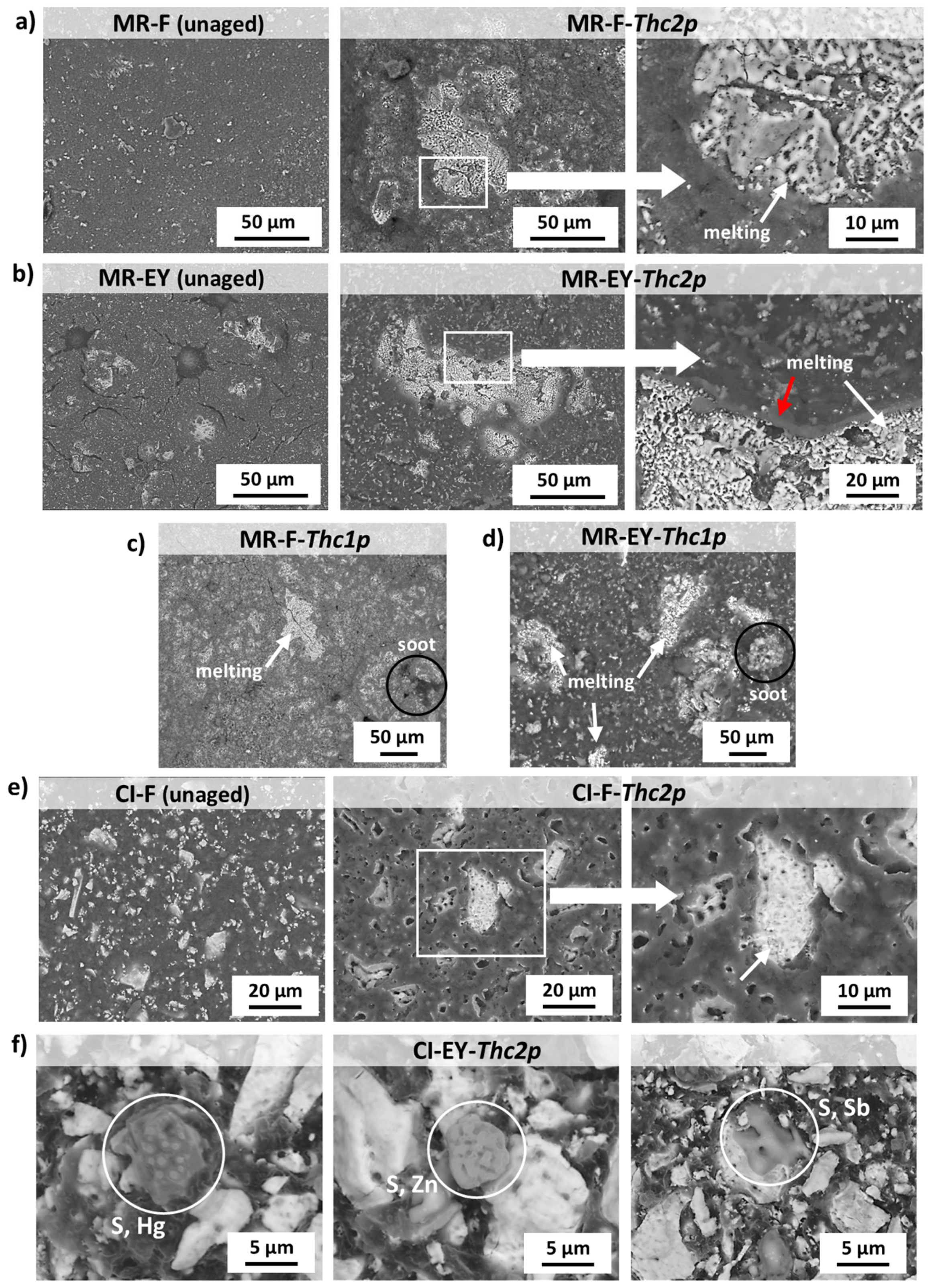

- The painting mock-ups’ micromorphology and elemental composition were studied using a FEI Quanta200 environmental scanning electron microscope (Hillsboro, OR, USA) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) in both secondary (SE) and backscattered electron (BSE) detection modes. Observation conditions included a working distance of ~10 mm, accelerating potential of 20 kV, and specimen current of ~60 mA.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical and Mineralogical Composition of the Raw Materials (Pigments, Lime Putty, Aggregates, and Soot)

3.2. Determination of the Damage Thresholds: Pigments and Unaged Painting Mock-Ups

3.2.1. Determination of the Pigment Tablet Damage Thresholds (Thps)

3.2.2. Determination of the Damage Thresholds for Unaged Painting Mock-Ups (Thm)

3.3. Determination of the Fluence Required for Cleaning Artificially Aged Painting Mock-Ups (Thc)

3.4. Cleaning Effectiveness on Soot Removal

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of the Pigment Composition

4.2. Influence of the Painting Technique

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Venegas García, C.; Barrainkua Legid, A. La Conservación de Pintura Mural; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, A. Decoupling trends of emissions across EU regions and the role of environmental policies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.; Cardell, C.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Burgos-Cara, A.; Elert, K. Effect of proteinaceous binder on pollution-induced sulfation of lime-based tempera paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 123, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, N.; Borgioli, L.; Adrover Gracia, I. Pigmenti Nell’arte Dalla Preistoria Alla Rivoluzione Industriale; II Prato: Saonara, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Urosevic, M.; Yebra-Rodríguez, A.; Sebastián-Pardo, E.; Cardell, C. Black soiling of an architectural limestone during two-year term exposure to urban air in the city of Granada (S Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 414, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, P.; Carrizo, L.; Thomachot-Schneider, C.; Gibeaux, S.; Alonso, F.J. Influence of surface finish and composition on the deterioration of building stones exposed to acid atmospheres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horemans, B.; Cardell, C.; Bencs, L.; Kontozova-Deutsch, V.; De Wael, K.; Van Grieken, R. Evaluation of airborne particles at the Alhambra monument in Granada, Spain. Microchem. J. 2011, 99, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Russa, M.F.; Fermo, P.; Comité, V.; Belfiore, C.M.; Barca, D.; Cerioni, A.; De Santis, M.; Barbagallo, L.F.; Ricca, M.; Ruffolo, S.A. The Oceanus statue of the Fontana di Trevi (Rome): The analysis of black crust as a tool to investigate the urban air pollution and its impact on the stone degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 593–594, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, V.; Miani, A.; Ricca, M.; La Russa, M.; Pulimeno, M.; Fermo, P. The impact of atmospheric pollution on outdoor cultural heritage: An analytic methodology for the characterization of the carbonaceous fraction in black crusts present on stone surfaces. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Roy, K.; Barman, P.; Rabha, S.; Bora, H.K.; Khare, P.; Konwar, R.; Saikia, B.K. Chemical and toxicological studies on black crust formed over historical monuments as a probable health hazard. J. Hazard Mater. 2024, 464, 132939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallmann, T.R.; Harley, R.A. Evaluation of mobile source emission trends in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D14305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calparsoro, E.; Maguregui, M.; Giakoumaki, A.; Morillas, H.; Madariaga, J.M. Evaluation of black crust formation and soiling process on historical buildings from the Bilbao metropolitan area (north of Spain) using SEM-EDS and Raman microscopy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 9468–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS principles for the preservation and conservation-restoration of wall paintings. In Proceedings of the 14th ICOMOS General Assembly, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 2–4 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, T.; Pozo, S.; Paz, M. Sulphur and oxygen isotope analysis to identify sources of sulphur in gypsum-rich black crusts developed on granites. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482–483, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, M.; Pironti, C.; Comité, V.; Bergomi, A.; Fermo, P.; Bontempo, L.; Camin, F.; Proto, A.; Motta, O. A multi-analytical approach for the identification of pollutant sources on black crust samples: Stable isotope ratio of carbon, sulphur, and oxygen. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P.; Biscontin, G. Origin, characteristics and morphology of weathering crusts on Istria stone in Venice. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravelaki, P.V.; Zafiropulos, A.V.; Kilikoglou, V.; Kalaitzaki, M.; Fotakis, C. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy as a diagnostic technique for the laser cleaning of marble. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 1997, 52, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouli, P.; Oujja, M.; Castillejo, M. Practical issues in laser cleaning of stone and painted artefacts: Optimisation procedures and side effects. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2012, 106, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmus, J.F.; Murphy, C.G.; Munk, W.H. Studies on the interaction of laser radiation with art artifacts. In Developments in Laser Technology II: Proceedings of the SPIE 0041, San Diego, CA, USA, 1 March 1974; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA. [CrossRef]

- Gaetani, M.C.; Santamaria, U. The laser cleaning of wall paintings. J. Cult. Herit. 2000, 1, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekede, L. Lasers: A preliminary study of their potential for the cleaning and uncovering of wall paintings. In Lacona I, Laser in the Conservation of Artworks; Kautek, W., Konig, E., Eds.; Mayer & Comp: Vienna, Austria, 1997; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dragasi, E.; Minos, N.; Pouli, P.; Fotakis, C.; Zanini, A. Laser cleaning studies on wall paintings; a preliminary study of various laser cleaning regimes. In Lacona VI, Laser in the Conservation of Artworks; Nimmrichter, J., Kautek, W., Schreiner, M., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brygo, F.; Dutouquet, C.; Le Guern, F.; Oltra, R.; Semerok, A.; Weulersse, J.M. Laser fluence, repetition rate and pulse duration effects on paint ablation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouli, P.; Selimis, A.; Georgiou, S.; Fotakis, C. Recent studies of laser science in paintings conservation and research. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Torres, R.; Martín, M.; Castillejo, M.; Sánchez-Cortés, S.; Domingo, C.; García-Ramos, J.V.; Sánchez-Cortés, S. Spectroscopic Analysis of Pigments and Binding Media of Polychromes by the Combination of Optical Laser-Based and Vibrational Techniques. Appl. Spectrosc. 2001, 55, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teule, R.; Scholten, H.; van den Brink, O.F.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Zafiropulos, V.; Hesterman, R.; Castillejo, M.; Martín, M.; Ullenius, U.; Larsson, I.; et al. Controlled UV laser cleaning of painted artworks: A systematic effect study on egg tempera paint samples. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo, M.; Martín, M.; Oujja, M.; Rebollar, E.; Domingo, C.; García-Ramos, J.V.; Sánchez-Cortés, S. Effect of wavelength on the laser cleaning of polychromes on wood. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo, M.; Martín, M.; Oujja, M.; Santamaría, J.; Silva, D.; Torres, R.; Manousaki, A.; Zafiropulos, V.; Brink, O.F.v.D.; Heeren, R.M.; et al. Evaluation of the chemical and physical changes induced by KrF laser irradiation of tempera paints. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon Sobott, R.J.; Heinze, T.; Neumeister, K.; Hildenhagen, J. Laser interaction with polychromy: Laboratory investigations and on-site observations. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordalo, R.; Morais, P.J.; Gouveia, H.; Young, C. Laser cleaning of easel paintings: An overview. Laser Chem. 2006, 2006, 90279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspard, S.; Oujja, M.; Moreno, P.; Méndez, C.; García, A.; Domingo, C.; Castillejo, M. Interaction of femtosecond laser pulses with tempera paints. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 2675–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oujja, M.; Pouli, P.; Fotakis, C.; Castillejo, M.; Domingo, C. Analytical Spectroscopic Investigation of Wavelength and Pulse Duration Effects on Laser-Induced Changes of Egg-Yolk-Based Tempera Paints. Appl. Spectrosc. 2010, 64, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounos, G.; Selimis, A.; Georgiou, S.; Rebollar, E.; Castillejo, M.; Bityurin, N. Dependence of ultraviolet nanosecond laser polymer ablation on polymer molecular weight: Poly(methyl methacrylate) at 248 nm. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 114323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Herguedas, L.; Jiménez-Desmond, D.; Ricci, C.; Zenucchini, F.; Rivas, T.; Cardell, C.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S. Influence of pulse duration on the effects induced by three Nd:YAG lasers operating at 1064 nm to tempera paintings mock-ups. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 76, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Herguedas, L.; Rivas, T.; Ramil, A.; Jiménez-Desmond, D.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S. Susceptibility of different pigments to irradiation by two lasers with different pulse duration and wavelength. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 706, 163581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, A.; Hill, A.E.; Fourrier, T.; Burgio, L.; Clark, R.J.H. The effects of UV laser light radiation on artists’ pigments. J. Cult. Herit. 2000, 1, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappé, M.; Hildenhagen, J.; Dickmann, K.; Bredol, M. Laser irradiation of medieval pigments at IR, VIS and UV wavelengths. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, S.; Salimbeni, R. Advances in laser cleaning of artwork and objects of historical interest: The optimized pulse duration approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofini, D.; Cacciari, I.; Siano, S. Multi-pulse laser irradiation of cadmium yellow paint films: The influence of binding medium and particle aggregates. Measurement 2018, 118, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. Materiales y Técnicas del Arte; Hermann Blume Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Desmond, D.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Arizzi, A. The fresco wall painting techniques in the Mediterranean area from Antiquity to the present: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Desmond, D.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Arizzi, A.; López-Martínez, T. Physico-Chemical Compatibility of an Aqueous Colloidal Dispersion of Silica Nano-Particles as Binder for Chromatic Reintegration in Wall Paintings. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovesan, R.; Mazzoli, C.; Maritan, L.; Cornale, P. Fresco and lime-paint: An experimental study and objective criteria for distinguishing between these painting techniques. Archaeometry 2012, 54, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Rivas, T.; Dionísio, A.; Barral, D.; Cardell, C. Effect of a SO2 rich atmosphere on tempera paint mock-ups. Part 1: Accelerated aging of smalt and Lapis Lazuli-based paints. Minerals 2020, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindley, G.W.; Brown, G. Crystal Structures of Clay Minerals and Their X-Ray Identification; Mineralogical Society: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11664-4:2008(E)/CIE S 014-4/E:2007; Colorimetry-Part 4: CIE 1976 L* a* b* Colour Space. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Mokrzycki, W.; Tatol, M. Color difference Delta E-A survey Colour difference ∆E-A survey. Mach. Graph. Vis. 2011, 20, 383–411. [Google Scholar]

- Riederer, J. Egyptian Blue. In Artists Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; West Fitzhugh, E., Ed.; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Plesters, J. Ultramarine Blue, Natural and Artificial. In Artists Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; Roy, A., Ed.; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 1993; Volume 2, pp. 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Grissom, C.A. Green Earth. In Artists Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; Feller, R.L., Ed.; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 1986; Volume 1, pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Baitimirova, M.; Katkevics, J.; Baumane, L.; Bakis, E.; Viksna, A. Characterization of functional groups of airborne particulate matter. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 49, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senesi, N.; Milano, T.M.; Sposito, G. Molecular and metal chemistry of leonardite humic acid in comparison to typical soil humic acids. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Peat Production and Use—Peat 90, Jyväskylä, Finland, 1 August 1990; pp. 412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Senesi, N.; Steelink, C. Application of ESR spectroscopy to the study of humic substances. In Humic Substrances II: In Search of Structure, Chichester; Hayes, M.H.B., MacCarthy, P., Malcolm, R.L., Swift, R.S., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 373–408. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Carrasco, L.; Torrens-Martín, D.; Morales, L.M.; Martínez-Ramírez, S. Infrared spectroscopy in the analysis of building and construction materials. In Infrared Spectroscopy: Materials Science, Engineering and Technology; Theophanides, T., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Derrick, M.R.; Stulik, D.; Landry, J.M. Scientific Tools for Conservation. In Infrared Spectroscopy in Conservation Science; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nodari, L.; Ricciardi, P. Non-invasive identification of paint binders in illuminated manuscripts by ER-FTIR spectroscopy: A systematic study of the influence of different pigments on the binders’ characteristic spectral features. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, R.; Prati, S.; Quaranta, M.; Joseph, E.; Kendix, E.; Galeotti, M. Attenuated total reflection micro FTIR characterisation of pigment-binder interaction in reconstructed paint films. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 392, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, C.W.; Matori, K.A.; Lim, W.F.; Schmid, S.; Zainuddin, N.; Wahab, Z.A.; Alassan, Z.N.; Zaid, M.H.M. Effects of Calcination on the Crystallography and Nonbiogenic Aragonite Formation of Ark Clam Shell under Ambient Condition. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 1, 2914368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgines, M.; Chen, J.J.; Bouillon, C. Overview about the use of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to study cementitious materials. In Materials Characterisation VI: Computational Methods and Experiments; Brebbia, C.A., Klemm, A., Eds.; WIT Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 77, pp. 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayabaş, A.; Yildirim, E. New approaches with ATR-FTIR, SEM, and contact angle measurements in the adaptation to extreme conditions of some endemic Gypsophila L. taxa growing in gypsum habitats. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 270, 120843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genestar, C.; Palou, J. SEM-FTIR spectroscopic evaluation of deterioration in an historic coffered ceiling. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 384, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirtit, P.; Appolonia, L.; Casoli, A.; Ferrari, R.P.; Laurenti, E.; Amisano Canesi, A.; Chiari, G. Spectrochemical and structural studies on a Roman sample of Egyptian blue. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1995, 51, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, M.M.; Martins, I.; Bruno, S.M.; Vaz, P.D.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A.; Rudić, S.; Nolasco, M.M. Shedding Light on Cuprorivaite, the Egyptian Blue Pigment: Joining Neutrons and Photons for a Computational Spectroscopy Study. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 4961–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Chervonnyi, A.D. Infrared Spectroscopy of Minerals and Related Compounds; Springer International Publishing: New York, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.L.; Lane, M.D.; Dyar, M.D.; Brown, A.J. Reflectance and emission spectroscopy study of four groups of phyllosilicates: Smectites, kaolinite-serpentines, chlorites and micas. Clay Miner. 2008, 43, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanost, A.; Gimat, A.; de Viguerie, L.; Martinetto, P.; Giot, A.C.; Clémancey, M.; Blondin, G.; Gaslain, F.; Glanville, H.; Walter, P.; et al. Revisiting the identification of commercial and historical green earth pigments. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 584, 124035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, R.; Pagnin, L.; Anghelone, M.; Moretto, L.M.; Orsega, E.F.; Schreiner, M. Pigment and Binder Concentrations in Modern Paint Samples Determined by IR and Raman Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7401–7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.L.; Xu, H.B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.H. Reductive conversion of hexavalent chromium in the preparation of ultra-fine chromia powder. J. Phys. Chem. Sol. 2006, 67, 2589–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Qin, X.F.; Meng, Y.F.; Guo, Z.L.; Yang, L.X.; Ming, Y.F. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2013, 16, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, W.; El Aref, M.; Gaupp, R. Spectroscopic characterization of iron ores formed in different geological environments using FTIR, XPS, Mössbauer spectroscopy and thermoanalyses. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 136, 1816–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrichs, T.; Drotleff, A.M.; Ternes, W. Determination of heat-induced changes in the protein secondary structure of reconstituted livetins (water-soluble proteins from hen’s egg yolk) by FTIR. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legan, L.; Retko, K.; Peeters, K.; Knez, F.; Ropret, P. Investigation of proteinaceous paint layers, composed of egg yolk and lead white, exposed to fire-related effects. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahur, S.; Teearu, A.; Leito, I. ATR-FT-IR spectroscopy in the region of 550–230 cm−1 for identification of inorganic pigments. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010, 75, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Jiménez-Desmond, D.; De Villalobos, L.; Mato, A.; Dionísio, A.; Rivas, T.; Cardell, C. SO2-Induced Aging of Hematite- and Cinnabar-Based Tempera Paint Mock-Ups: Influence of Binder Type/Pigment Size and Composition. Minerals 2023, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, A.; Colombini, M.P.; Nevin, A.; Melessanaki, K.; Pouli, P.; Fotakis, C. Multianalytical Study of Laser Pulse Duration Effects in the IR Laser Cleaning of Wall Paintings from the Monumental Cemetery of Pisa. Laser Chem. 2006, 2006, 39046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Papanikolaou, A.; Philippidis, A.; Melessanaki, K.; Rivas, T.; Pouli, P. Cleaning of gypsum-rich black crusts on granite using a dual wavelength Q-Switched Nd:YAG laser. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 226, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, P.; Giorgi, R.; Chelazzi, D. The degradation of wall paintings and stone: Specific ion effects. Curr. Opin. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2016, 23, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.M.; Ferro, M.C.; Gaspar, G.; Fernandes, A.J.S.; Valente, M.A.; Costa, F.M. Laser-Induced Hematite/Magnetite Phase Transformation. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 7187–7193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettens, R.J.; Feller, R.L.; Chase, W.T. Vermilion and Cinnabar. In Artists Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; Roy, A., Ed.; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 1993; Volume 2, pp. 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Loredo, J.; Luque Cabal, C.; Garcia Iglesias, J. Conditions of formation of mercury deposits from the Cantabrian zone (Spain). Bull. Minéralogie 1988, 111, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Desmond, D.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S.; Arizzi, A. Outdoor durability of nano-sized silica-based chromatic reintegrations. Influence of exposure conditions and pigment composition. Dye. Pigment. 2025, 235, 112651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Visual Appearance | Suppliers Code | Pigment Code | Suppliers pigment Composition | Authors Pigment Composition by XRD | Semi-Quantitative Elemental Composition by XRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #100601 Egyptian blue | EB | Cuprorivaite | Cuprorivaite, CaCuSi4O10 Quartz, SiO2 | >1: Si, Cu, Ca <1: Al |

| #45010 Ultramarine blue, synthetic | UB | Sodium aluminium sulpho-silicate and kaolinite | Lazurite, Na3Ca(Al3Si3O12)S Sodalite, Na8Al6Si6O24Cl2 Nepheline, Na,K(Al4Si4O16) Kaolinite, Al2Si2O5(OH)4 | >1: Si, S, Al <1: Fe |

| #11010 Green Verona earth | GE | Celadonite | Glauconite, (K,Na)(Fe3+,Al,Mg)2(Si,Al)4O10(OH)2 Celadonite, K(Mg,Fe)Fe3+Si4O10(OH)2 Muscovite, KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 Calcite, CaCO3 Clinochlore, (Mg,Fe2+)5Al(Si3Al)O10(OH)8 Albite, NaAlSi3O8 Montmorillonite, (Na,Ca)0,3(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2·nH2O Kaolinite, Al2Si2O5(OH)4 | >1: Si, Ca, Fe, Mg, Al, Ti <1: Mn |

| #44200 Chromium oxide green | CG | Chrome (III) oxide | Eskolaite, Cr2O3 | >1: Cr, Mg, Al <1: Ca, Mn |

| #48289 Iron oxide red | MR | Synthetic iron (III) oxide | Hematite, Fe2O3 | >1: Fe, Mg <1: Al, Mn, Cl, Ca |

| #10624 Cinnabar, chien t’ou | CI | Cinnabar | Cinnabar, HgS | >1: Hg, S, Si <1: Mo, Th, Rb, Nb, Sb, Ba, P, Fe, Al |

| Pigment Nature | Pigment ID | Thp | Unaged Samples | Thm | Aged Samples | Thc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot Size (cm) | Energy per Pulse (J/pulse) | Fluence (J/cm2) | Spot Size (cm) | Energy per Pulse (J/pulse) | Fluence (J/cm2) | Spot Size (cm) | Energy per Pulse (J/pulse) | Fluence (J/cm2) | ||||

| Silicate | EB | 0.510 | 0.030 | 0.147 | EB-F | 0.300 | 0.030 | 0.424 | EB-F | 0.300 | 0.020 | 0.283 |

| EB-EY | 0.350 | 0.030 | 0.321 | EB-EY | 0.350 | 0.020 | 0.214 | |||||

| UB | 0.450 | 0.012 | 0.075 | UB-F | 0.300 | 0.016 | 0.221 | UB-F | 0.300 | 0.010 | 0.141 | |

| UB-EY | 0.390 | 0.030 | 0.251 | UB-EY | 0.390 | 0.020 | 0.161 | |||||

| GE | 0.540 | 0.013 | 0.055 | GE-F | 0.300 | 0.030 | 0.424 | GE-F | 0.300 | 0.015 | 0.212 | |

| GE-EY | 0.330 | 0.018 | 0.210 | GE-EY | 0.330 | 0.016 | 0.187 | |||||

| Oxide | CG | 0.480 | 0.013 | 0.070 | CG-F | 0.480 | 0.023 | 0.127 | CG-F | 0.480 | 0.023 | 0.127 |

| CG-EY | 0.480 | 0.021 | 0.116 | CG-EY | 0.480 | 0.022 | 0.122 | |||||

| MR | 0.570 | 0.007 | 0.027 | MR-F | 0.450 | 0.012 | 0.075 | MR-F | 0.450 | 0.028 | 0.176 | |

| MR-EY | 0.450 | 0.008 | 0.047 | MR-EY | 0.450 | 0.032 | 0.201 | |||||

| Sulphide | CI | 0.570 | 0.007 | 0.027 | CI-F | 0.570 | 0.004 | 0.014 | CI-F | 0.420 | 0.016 | 0.115 |

| CI-EY | 0.570 | 0.004 | 0.016 | CI-EY | 0.420 | 0.014 | 0.101 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Desmond, D.; D’Ayala, K.; Andrés-Herguedas, L.; Barreiro, P.; Dionísio, A.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S. Influence of Pigment Composition and Painting Technique on Soiling Removal from Wall Painting Mock-Ups Using an UV Nanosecond Nd:YAG Laser. Minerals 2026, 16, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010010

Jiménez-Desmond D, D’Ayala K, Andrés-Herguedas L, Barreiro P, Dionísio A, Pozo-Antonio JS. Influence of Pigment Composition and Painting Technique on Soiling Removal from Wall Painting Mock-Ups Using an UV Nanosecond Nd:YAG Laser. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Desmond, Daniel, Kateryna D’Ayala, Laura Andrés-Herguedas, Pablo Barreiro, Amélia Dionísio, and José Santiago Pozo-Antonio. 2026. "Influence of Pigment Composition and Painting Technique on Soiling Removal from Wall Painting Mock-Ups Using an UV Nanosecond Nd:YAG Laser" Minerals 16, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010010

APA StyleJiménez-Desmond, D., D’Ayala, K., Andrés-Herguedas, L., Barreiro, P., Dionísio, A., & Pozo-Antonio, J. S. (2026). Influence of Pigment Composition and Painting Technique on Soiling Removal from Wall Painting Mock-Ups Using an UV Nanosecond Nd:YAG Laser. Minerals, 16(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010010