This Discussion synthesizes the multivariate and univariate patterns documented in the Results through the lens of archeological and technological questions. The following subsections are organized around five interpretive themes: (4.1) geochemical interpretation of raw pigment compositions and their implications for material selection; (4.2) universal and pigment-specific discriminating elements and what they reveal about geological vs. cultural factors controlling compositional variation; (4.3) shelter-specific signatures and within-shelter heterogeneity as evidence for multiple painting episodes and technological complexity; (4.4) insights into pigment technology and raw material procurement; (4.5) methodological considerations, limitations, and future directions; and (4.6) archaeological and technological implications.

4.1. Geochemical Interpretation of Pigment Compositions

The elemental data from pXRF, prior to any transformation or statistical treatment, provide a foundational understanding of the materials present in pigmented rock surfaces at Albarracín. However, critical interpretation requires acknowledging that these measurements capture composite signals integrating substrate contribution (dominant, due to pXRF penetration depth of 1–5 mm exceeding pigment thickness of <50 μm by orders of magnitude) with genuine pigment composition. By comparing the pigment compositions (

Table S1) with those of the underlying rock substrates of the shelters (

Table S2), we identify elements showing clear enrichment in pigments relative to substrate baselines (signatures consistent with intentional addition or mineral selection).

Potential pigment materials are proposed based on key elemental indicators: Fe enrichment for iron oxides; Mn enrichment for manganese oxide minerals; P enrichment for phosphate-rich components potentially including bone-derived materials; Al-Si associations for aluminosilicate clay mineral phases (likely of the kaolinite group, though Si/Al ratios exceed pure kaolinite stoichiometry due to quartz substrate contribution); and Ca-S covariation for gypsum. Elements tracking substrate levels closely (particularly Ba, Sr-Si-Mg triad, Ti) are interpreted as primarily geological in origin, enabling robust site discrimination but limiting direct ‘recipe’ interpretation.

These interpretations remain necessarily tentative, as pXRF provides elemental composition but cannot definitively identify crystalline phases or distinguish between mineralogically distinct materials with similar elemental ratios. Mineralogical confirmation requires complementary techniques such as X-ray diffraction or Raman spectroscopy (see

Section 4.5).

Relationship between visual color and inferred composition: Although no quantitative colorimetric measurements were acquired, the visual color categories correspond logically to the elemental patterns observed. Red pigments show systematic Fe enrichment consistent with iron oxide chromophores (hematite/goethite); inter-shelter Fe variability (0.64%–2.14%) likely corresponds to perceptible color differences, with higher Fe concentrations typically producing deeper, more saturated reds. Black pigments divide into Mn-enriched samples (consistent with dark manganese oxides, pyrolusite/manganite) and Mn-poor samples (consistent with carbon-based blacks, whether charcoal or bone char, both producing deep blacks through light absorption rather than mineral pigmentation). White pigments show Ca-S-Al-Si associations consistent with gypsum and aluminosilicate clay minerals (white to cream-colored depending on iron impurity content). Quantitative colorimetric analysis combined with mineralogical identification represents an important future research direction for establishing precise color-composition relationships and detecting subtle within-category hue variations.

Ceja de Piezarrodilla: The paintings at this shelter are characterized by complex recipes and layering. Most black and all black-over-white samples show high Mn (0.33%–2.11%) relative to the substrate (<LOD), supporting the use of manganese oxides like pyrolusite as chromophores. In blacks lacking Mn presence (samples 14 and 15), the use of teruelite —a rare, ferroan variety of dolomite known for its high Fe content (approximately 10% iron substitution in the magnesium site) and characteristic dark brown to black coloration— may be considered (Mg contents of ca. 0.4% in the paintings vs. <LOD in the rock substrate and the rest of the samples), although carbon-based materials like charcoal cannot be ruled out, as they are not detectable by XRF. P concentrations (0.14–1.01%) exceed substrate levels (<LOD) in several instances, indicating the use of hydroxyapatite (Ca

5(PO

4)

3(OH)), likely from bone. Al and Si levels (up to 3.19% and 36.44%, respectively) suggest aluminosilicate clay mineral binders, likely of the kaolinite group, with clear enrichments over substrate (Al 1.63%, Si 13.83%) indicating deliberate addition, while high Ca and S contents largely track the substrate (mean S content in paintings 8.95% vs. 9.09% in substrate), pointing to gypsum from geological sources rather than recipes. These findings align with previous reports by Orera Clemente et al. [

11], who identified an anhydrite-gypsum crust associated with a calcite flowstone at this site. Their scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX) analyses confirmed that black pigments contained manganese oxides, presumably pyrolusite and/or manganite, with additional presence of charcoal and iron oxides (perhaps magnetite, Fe

3O

4).

Hoya de Navarejos II, III, IV, and V: The shelters at Hoya de Navarejos share a common materials base. In Hoya de Navarejos III, the white, pale red, and gray pigments are dominated by Ca (~17.35%) minerals. The white pigments show dramatic enrichment in S (mean 5.06% vs. 1.02% in rock substrate), confirming that gypsum was the principal white component. The subtle red and gray tones appear to be achieved by adding small quantities of iron oxides (hematite) and manganese oxides (pyrolusite), respectively. Black pigments at this shelter vary from Mn-rich (2.11%), indicative of pyrolusite, to Mn-absent (<LOD) with P (0.06–0.29%), suggesting bone char or charcoal. The samples from Hoya de Navarejos IV and V, though fewer, fit this pattern. The red pigments from shelter V are defined by their Fe content (mean 1.2%), an enrichment over the substrate rock (0.96%), supporting their classification as hematite-rich ochres.

Cabras Blancas: The pigment samples from Cabras Blancas, all classified as white-over-black, are remarkably homogeneous and geochemically distinct from their substrate. The substrate here is calcareous (17.82% Ca), yet the white pigment layer is significantly enriched in Ca to an average of 23.26%. This enrichment, coupled with higher S content, indicates gypsum as a primary material. The consistent presence of low but detectable Si (~3.7%) and Al (~1.1%) suggests an aluminosilicate clay mineral component, possibly of the kaolinite group, used as a binder or extender in the gypsum paste. However, the observed Si/Al ratio (~3.4) substantially exceeds the stoichiometric ratio for pure kaolinite (~1.18 by weight), indicating significant excess silica from the quartz-rich

Rodeno sandstone substrate. This exemplifies the challenge of mineral identification from pXRF elemental ratios alone: while the Al-Si association is consistent with clay minerals, the quantitative ratios reflect mixed pigment-substrate signals rather than pure mineral composition. The low P (0–0.023%) content and absence of Mn imply carbon-based blacks beneath (i.e., charcoal), not bone char. These results correspond with findings by Orera Clemente et al. [

28], who used Raman spectroscopy and SEM-EDX to conclude that the pigment employed for the white paintings was gypsum. Regarding the black background, they noted that —based on SEM-EDX data— the composition of the black patina on which the paintings were made could be associated with the use of charcoal, although a biological origin could not be ruled out.

Prado Navazo: This shelter stands out for its extensive use of phosphate-based white: elevated P (mean ~0.45%) in conjunction with Ca strongly suggests the use of hydroxyapatite, likely in the form of calcined bone (bone ash), which would have been systematically mixed with a clay mineral (aluminosilicates consistent with kaolinite-group minerals, inferred from Si and Al) base and, in some samples, with gypsum—evidenced by significant Ca and S levels (up to 5.55%). However, low S contents (0.62–0.641%) in other white samples indicate either variability in recipes or substrate influence. The black pigments are less distinct chemically, with a composition largely mirroring the associated whites but with a slight increase in Ti, possibly indicating the use of Ti-bearing minerals or a different clay source. These could be charcoal-based, except for sample 55, in which the Mg content (0.54%) would be compatible with the use of teruelite as a chromophore.

Tío Campano: The three red samples from Tío Campano provide a clear signature for iron-based ochre. They possess the highest mean Fe concentration (2.14%) across all analyzed shelters, enriched over substrate (1.10%). This iron enrichment, combined with significant levels of Si (mean 9.78%) and Al (mean 2.36%), is highly characteristic of ferruginous clay, entirely consistent with the use of local Keuper system materials (hematite mixed with kaolinite-group clay minerals) for creating red pigments. The presence of Ca and S (1.07% in paints vs. 0.21% in substrate) suggests that gypsum may have been mixed in, perhaps to adjust the paint’s consistency or hue.

La Cocinilla del Obispo: The white and pale red pigments are again primarily composed of Ca and S, consistent with a gypsum base, with red shades likely achieved by adding small amounts of iron oxides (e.g., Keuper clays with hematite). Notably, sample 80 is also rich in Ti (0.22%) and K (1.22%), suggesting the use of a different, perhaps more micaceous or feldspar-rich, clay source compared to other sites. The single black sample (77) is distinguished by its elevated Mn (0.56%), supporting the interpretation of a manganese oxide pigment (pyrolusite), which appears to have been mixed into a gypsum paste, given the high Ca and S content.

Casa Forestal I, II, and V: The rock substrate at shelters I and II is Ca-rich (14.25%–18.40%), differing in Si content (11.15% and 5.56%, respectively), while at shelter V it is Ca-poor (0.32%) and Si-rich (41.31%), necessitating separate analysis of the white pigments. White pigments at shelters I and V are enriched in Ca, P, and S compared to the substrate, suggesting hydroxyapatite and gypsum, while those at shelter II are rich in Si and Al, indicating an aluminosilicate clay mineral base (likely kaolinite-group). The red pigments at Casa Forestal II are distinguished by a modest but consistent increase in Fe (mean 0.64%) compared to the rock (0.35%) and the whites (mean 0.35%), supporting the hypothesis of hematite addition to the base clay recipe.

These interpretations align with and extend earlier chemical analyses of Albarracín rock art. As Beltrán Martínez [

41] noted in 1968: “The chemical analyses conducted to date have only allowed us to verify the extreme degree of fossilization of the pigments and to determine the presence of iron, aluminum, and manganese. These consist of ochres and manganese and iron oxides, plus kaolin for white, in addition to hematite, limonite, sanguine, and charcoal” [tr.]. Our pXRF analyses confirm and substantially expand upon these early observations, providing quantitative data that reveals the complexity and variability of pigment recipes across the Albarracín shelters, while also identifying materials not previously reported, such as phosphate-based compounds from bone processing.

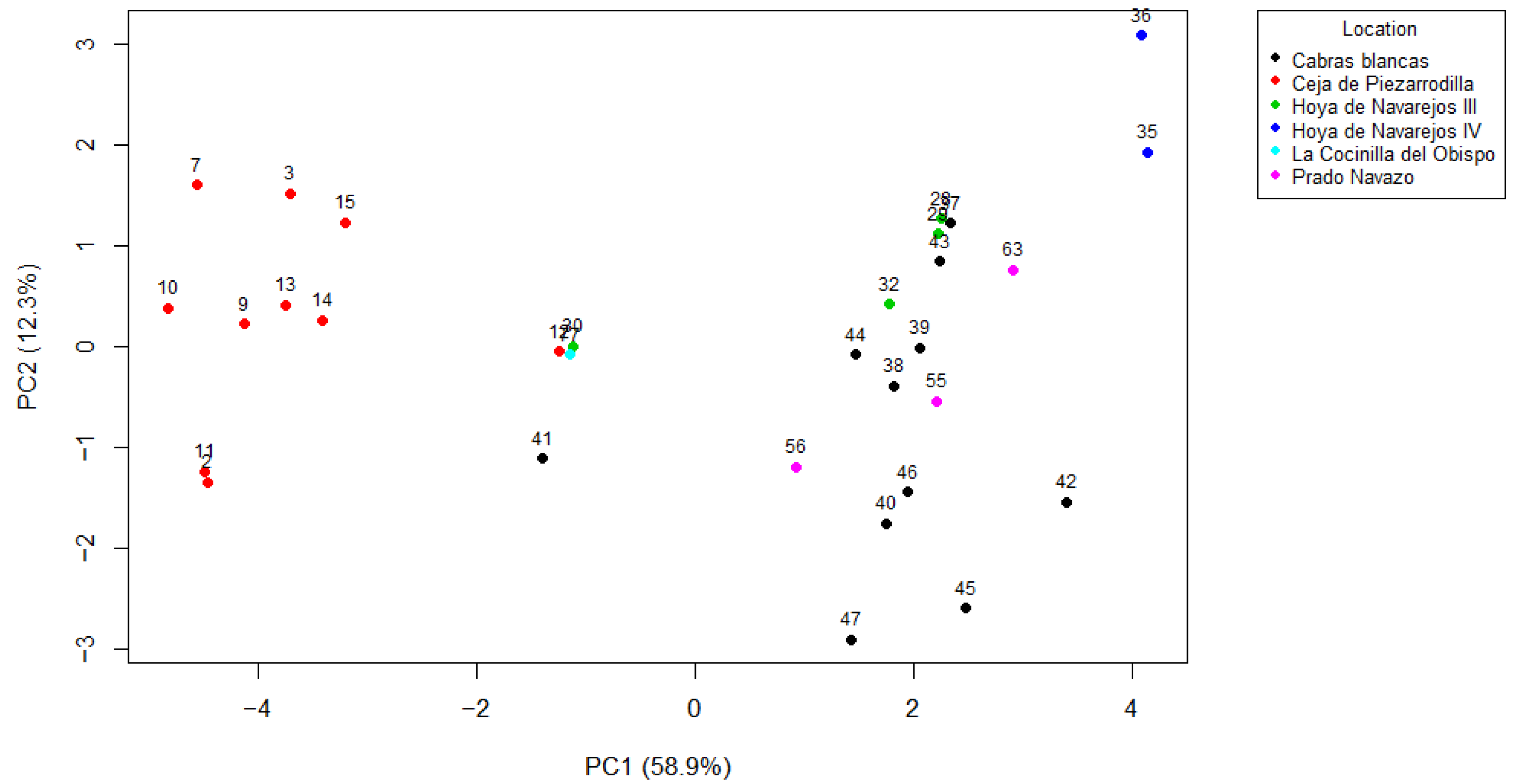

4.2. Universal and Pigment-Specific Discriminating Elements

The dominance of substrate-derived elements in multivariate discrimination must be interpreted carefully in an archeological context. The 92.6%–100% classification accuracies achieved by LDA reflect the strength of geological signatures, not necessarily the fidelity of pigment recipe reconstruction. In fact, the largest effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 8.0) invariably correspond to substrate-driven elements (Ba, Sr-Si-Mg), while elements with unambiguous pigment origins (Fe in reds, Mn in blacks where strongly elevated above substrate, P in suspected bone-char materials) show somewhat smaller but still very large effects (d = 2.87–7.50). This hierarchical pattern demonstrates that site discrimination is primarily a geological phenomenon enabling provenance fingerprinting and authentication of painted surfaces, while archaeological interpretation of technological choices must focus on secondary signals—elements clearly enriched in pigments over substrate, and compositional heterogeneity within shelters reflecting multiple painting episodes, diverse raw material sources, or varied preparation techniques.

Barium emerges as the sole element with universal discriminatory power across all pigment types, ranking as the top or second discriminator in each dataset (

Tables S9, S17 and S25). Its consistently extreme effect sizes in pairwise comparisons (the largest observed for any element) align with regional geological variations in the Hercynian materials of the Iberian Range [

42]. This pattern indicates that Ba primarily reflects substrate-derived signals rather than intentional additions, as confirmed by comparable concentrations in unpainted rock surfaces (

Table S2).

The dominance of Ba as a discriminator in the Albarracín sandstone substrates contrasts markedly with Levantine rock art sites on calcareous supports, where Roldán García et al. [

18] reported calcium as the overwhelmingly dominant element in all EDXRF spectra from Saltadora (Valltorta gorge, Castellón) due to the limestone bedrock contribution. In that limestone environment, the calcium signal from the substrate complicated pigment-substrate discrimination and required trace element analysis (Mn, As, Pb) to differentiate between pigment sources. At Albarracín, the relatively low calcium concentrations combined with the sandstone matrix allow barium’s more subtle geological variations to emerge as the primary discriminator—a pattern that would be masked in calcareous environments.

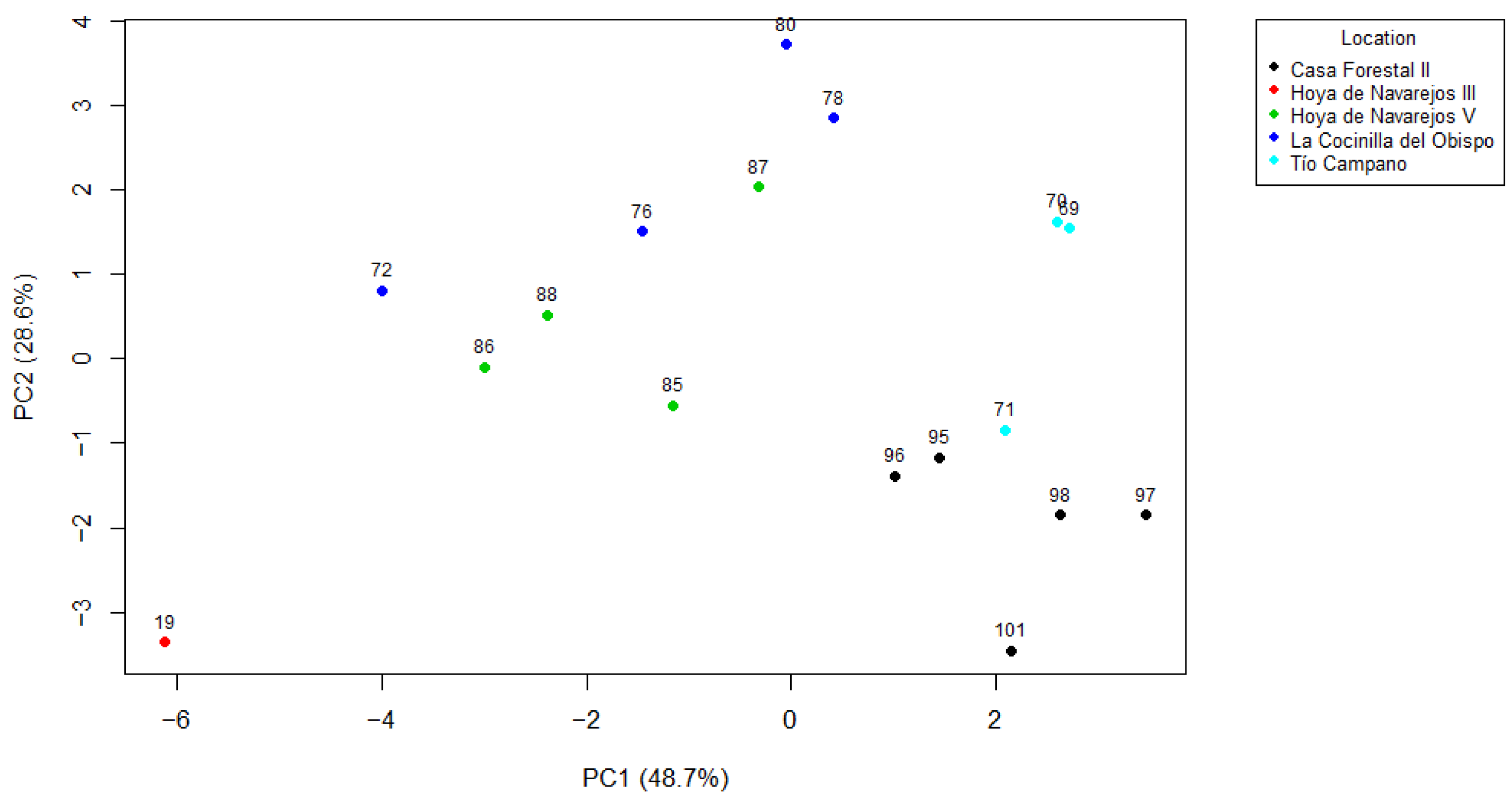

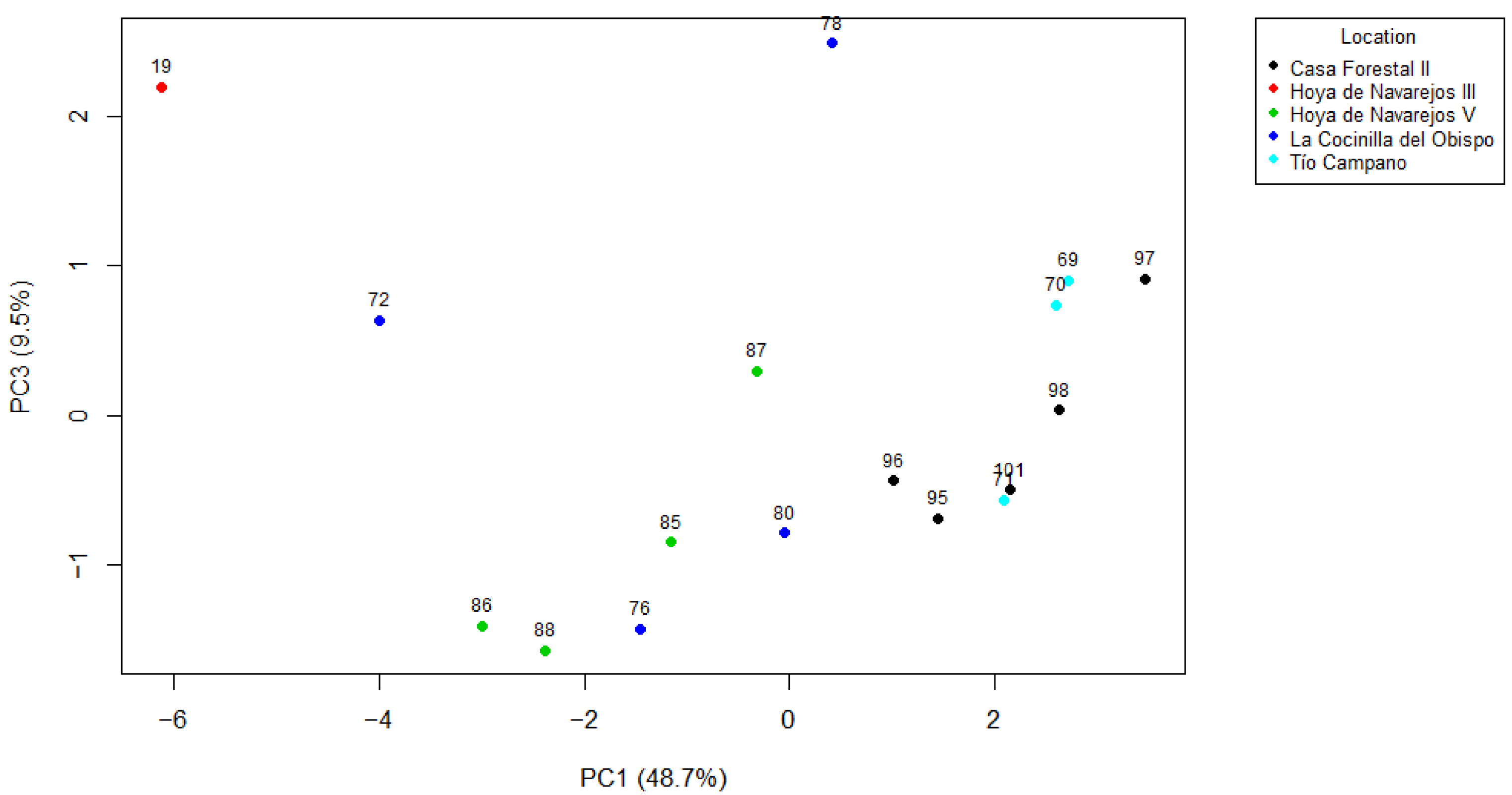

Other discriminators are markedly pigment-specific, reflecting chromophore selection and preparation. For red pigments, Fe dominates discrimination (

Table S25), with raw concentrations confirming hematite (α-Fe

2O

3)/goethite (Fe(OH)O) as the principal chromophore, consistent with identifications in prior studies of Levantine art [

11,

43]. The substantial inter-shelter Fe variation—Tío Campano showing approximately threefold higher mean Fe than Casa Forestal II (

Table S26)—suggests exploitation of different ochre sources with varying iron oxide content. The two red pigment samples falling outside standard classification—Hoya de Navarejos III (sample 19) and Cocinilla del Obispo (sample 78)—merit interpretive consideration despite their borderline outlier status. Sample 19 corresponds to a light-toned, pinkish (rather than red) depiction, with the compositional difference likely resulting from varied pigment load or density compared to other motifs on the same panel (Hoya de Navarejos III 20–25). The dimensions, execution technique, and morphology all indicate synchronous creation during a single stylistic phase, as confirmed by consistent readings from other sampling points on the same figure. In contrast, Cocinilla del Obispo 78 exhibits both coloration and morphological differences from other zoomorphic motifs in its shelter, strongly suggesting a distinct pigment composition derived from an alternate raw material source. These cases illustrate how statistical outliers can reflect genuine technological variability—whether through intentional recipe modification within a single painting episode or exploitation of different ochre deposits.

The Tío Campano samples, while not formal outliers, warrant specific discussion due to their distinctive characteristics. All three samples share strong internal compositional similarity despite originating from different figures, supporting synchronous panel execution. Their emergence as a well-defined cluster completely separate from other red pigments underscores both their tonal and stylistic distinctiveness within the Sierra de Albarracín corpus. These figures diverge substantially from the more common formal criteria of regional zoomorphic depictions, exhibiting a non-naturalistic stylistic tendency that suggests exclusion from the Levantine tradition sensu stricto. The chemical homogeneity within this atypical stylistic group demonstrates that compositional clustering can successfully identify culturally or chronologically distinct painting episodes, even when visual assessment alone might prove ambiguous.

Manganese distinguishes black pigments (

Table S17), but its distribution reveals technological heterogeneity both between and within shelters. Elevated Mn in specific samples (exceeding 0.5% and reaching >2% in some cases;

Table S1) indicates pyrolusite use, while Mn-absent or trace-level samples from the same shelters and across Hoya de Navarejos IV, Cabras Blancas, and Prado Navazo suggest carbon-based alternatives (see

Section 4.3).

White pigments generally lack a clear chromophore discriminator, instead relying on the Sr-Si-Mg triad (

Table S9), which exhibits identical statistical behavior across analyses—a hallmark of covariant substrate, suggesting minerals like celestite (SrSO

4) and dolomite/teruelite (CaMg(CO

3)

2) in the local sandstones (

Table S2).

Secondary patterns include the Zr-P-S triad in black pigments (

Table S17), potentially tracing apatite or zircon accessories, and ubiquitous S and Cl across all samples, including substrates (

Tables S1 and S2). The sulfur distribution shows site-specific patterns: at Ceja de Piezarrodilla, elevated S values in pigments align with high substrate levels, indicating geological origin. Conversely, at La Cocinilla del Obispo, anomalously high S in specific pigment samples against a low substrate background suggests Liesegang banding—periodic precipitation patterns concentrating sulfates such as gypsum (CaSO

4·2H

2O) in localized zones. Chlorine, showing more uniform distribution, likely derives from atmospheric deposition of Ebro Valley aerosols, as documented in regional geochemical surveys [

44].

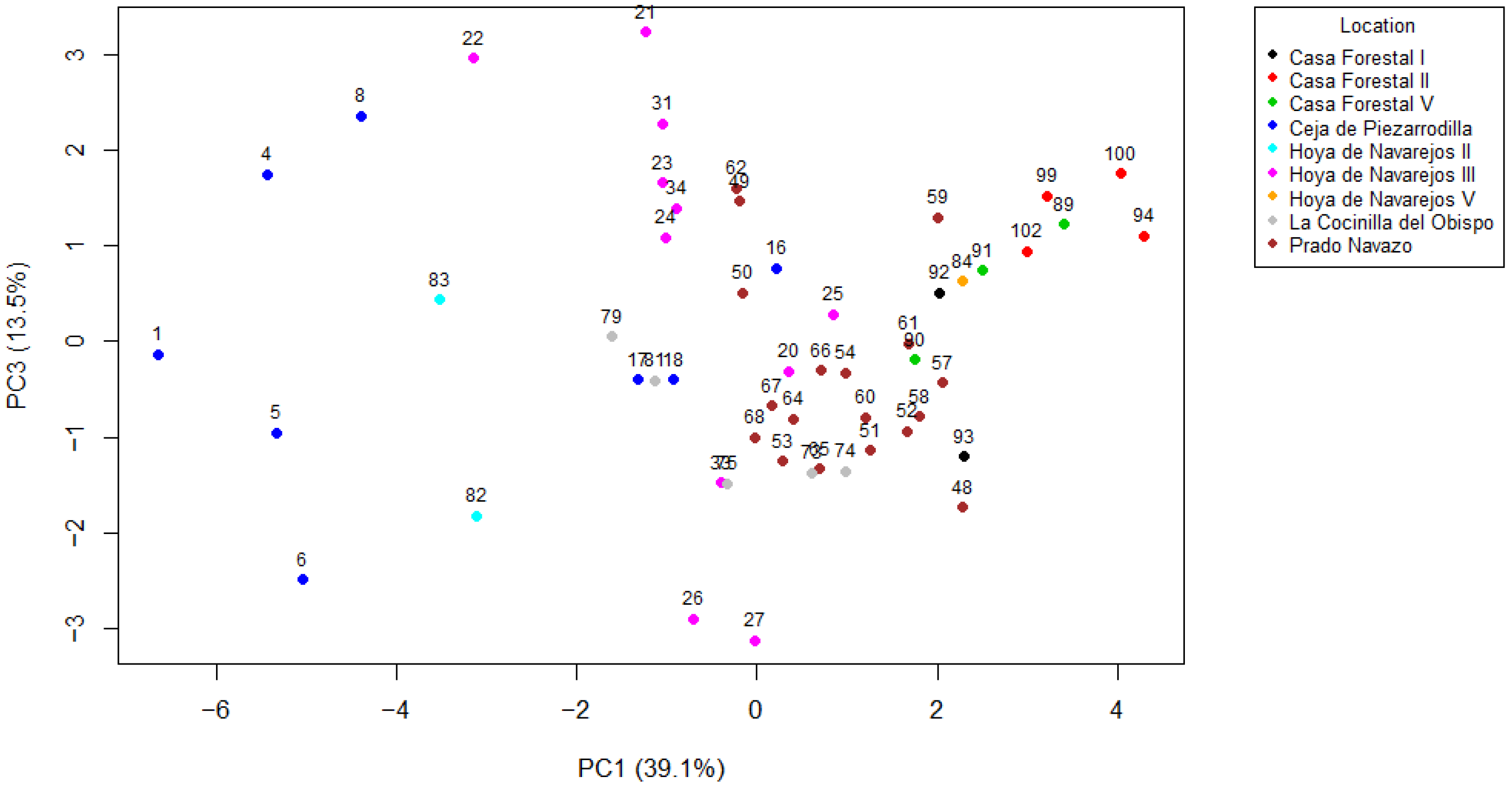

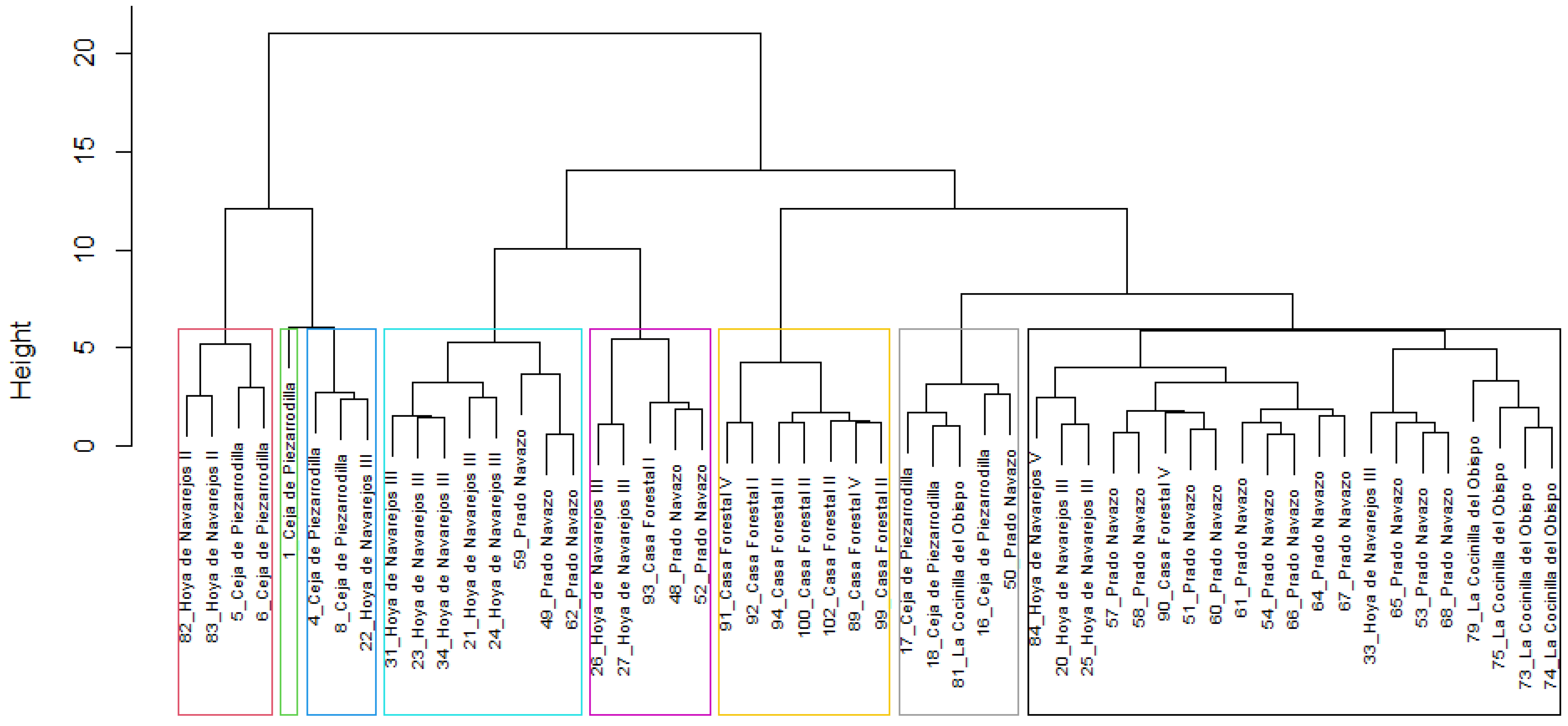

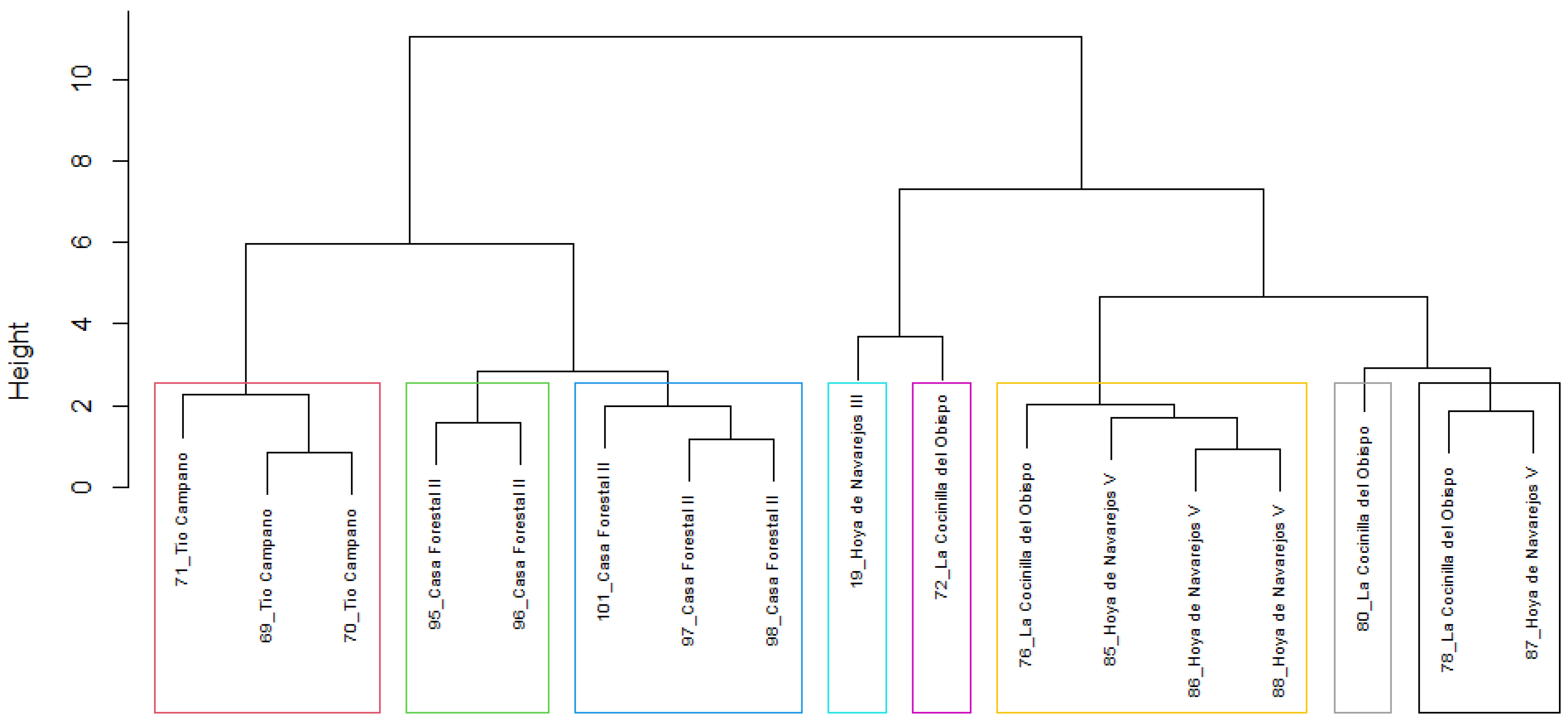

4.3. Shelter-Specific Signatures and Cross-Color Consistencies

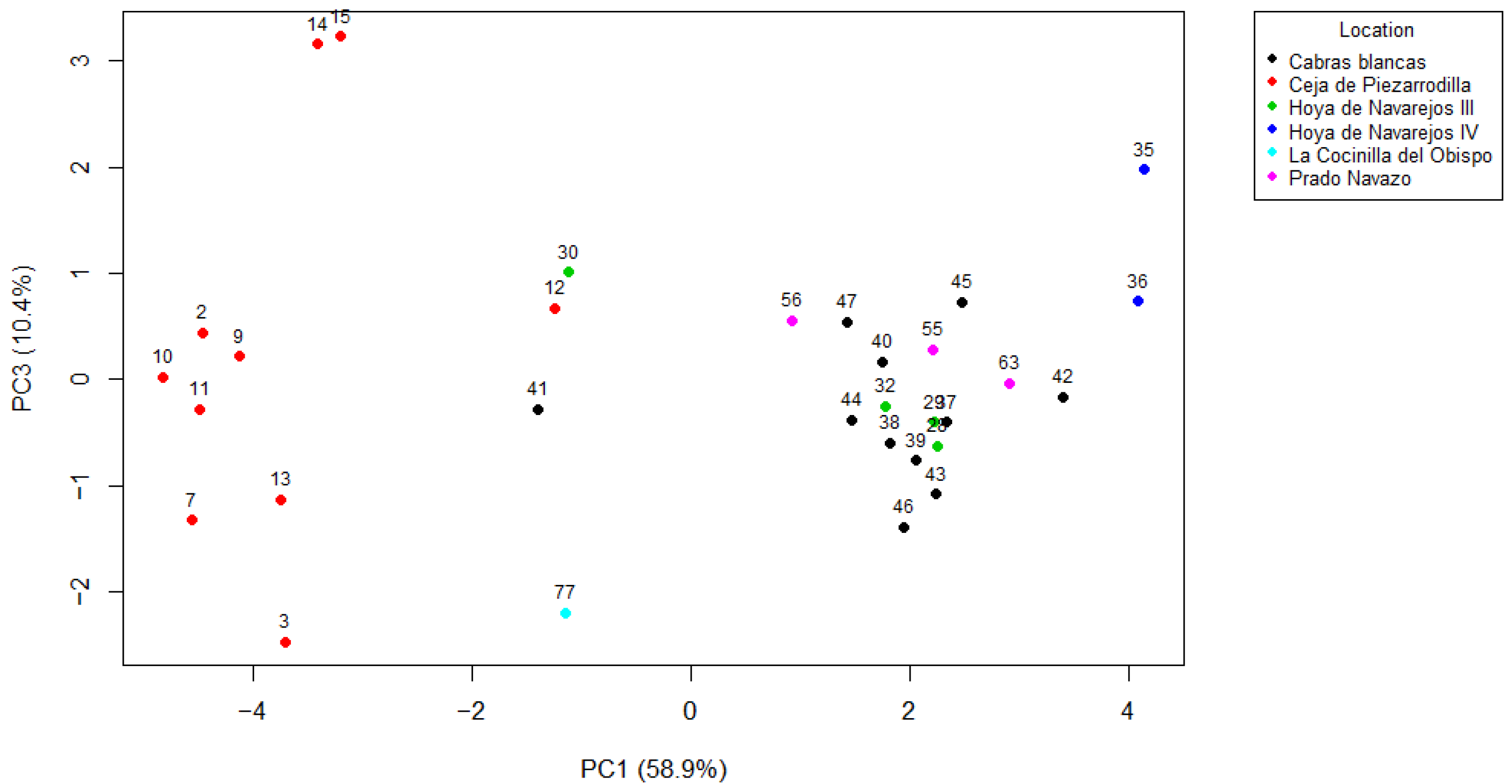

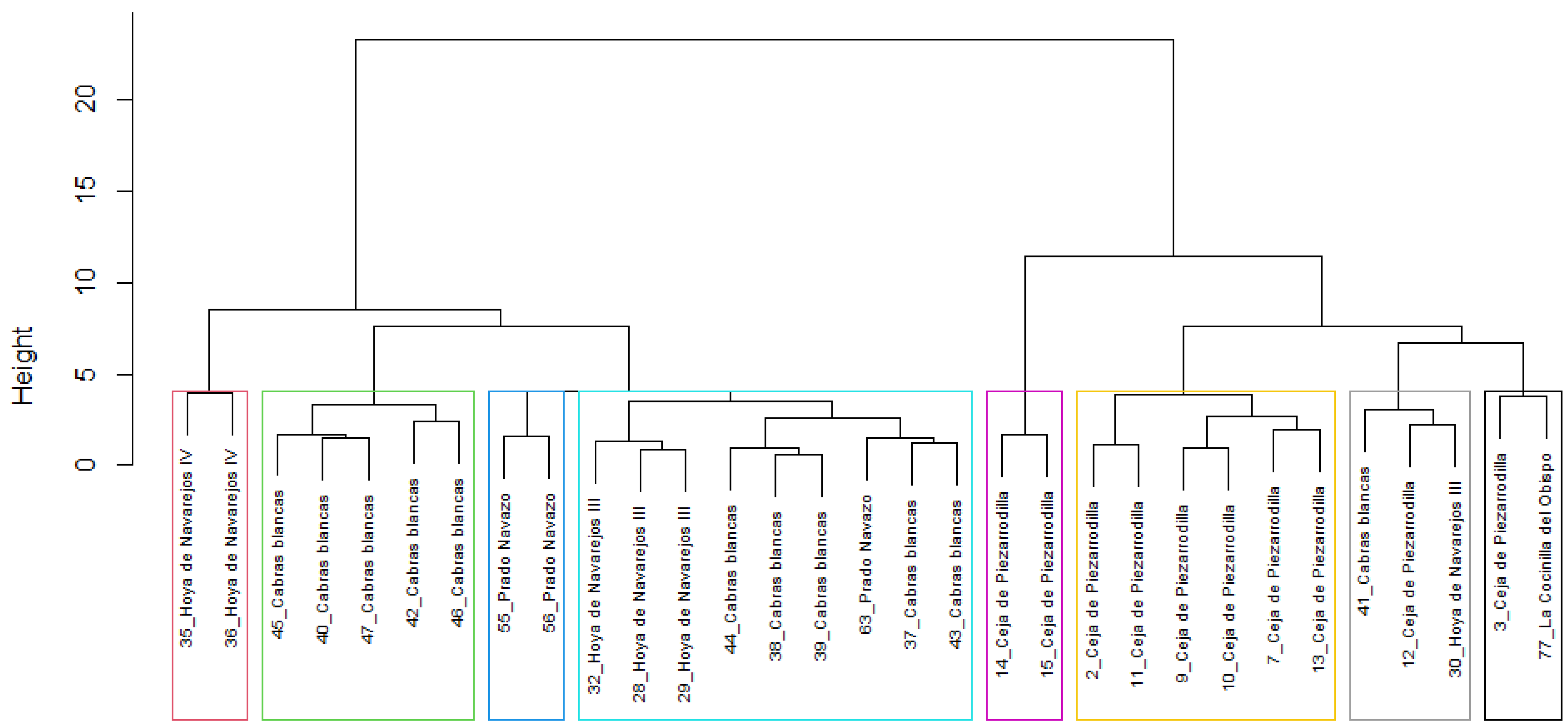

Pairwise Euclidean distances (

Tables S8, S16 and S24) and HCA reveal shelter clusters that vary by pigment color, indicating that geological signatures are modulated by anthropogenic choices. Four shelters provided sufficient samples (

n ≥ 3) for multiple colors, enabling cross-color comparisons: Ceja de Piezarrodilla, Hoya de Navarejos III, and Prado Navazo (white and black/black-over-white); Casa Forestal II (white and red).

Ceja de Piezarrodilla emerges as the most chemically complex shelter, exhibiting the highest diversity across white (

Table 2) and black (

Table 5) pigments. The shelter contains: high-Mn blacks indicating pyrolusite use, moderate-Mn layered samples, and Mn-absent blacks suggesting carbon-based alternatives—all coexisting within a single decorated panel. This heterogeneity—reflected in lower LDA accuracy (62.5% for white)—persists despite proximity to Hoya de Navarejos II and IV (distances 2.76 and 3.85, respectively), suggesting either localized substrate variability or multiple painting phases with different technologies.

The interpretation of white pigment outliers at this shelter merits particular attention. Sample 1, located at a contact zone between different chromatic elements, likely reflects a combined signal from white horns and overlying black repaint, explaining its distinct cluster identity. More intriguing is sample 5, corresponding to white horns, which shows the closest compositional similarity to a stylized human representation from Hoya de Navarejos II rather than to other white bovine figures with twisted-perspective horns (such as those from Hoya de Navarejos III or Prado del Navazo). These evident thematic and morphological differences—despite chemical correspondence—suggest that pigment recipes were not strictly determined by subject matter or style, but may reflect the use of different geological raw material sources even among morpho-stylistically similar representations.

Hoya de Navarejos III shows moderate consistency across colors (

Tables S8 and S16), yet exhibits the same internal technological heterogeneity as Ceja de Piezarrodilla—the shelter contains the highest single Mn value in a black pigment and Mn-free black samples (

Table S1), documenting deliberate material choices rather than simple substrate influence. Casa Forestal II displays color-dependent divergence: tight clustering for white (single cluster) but moderate diversity in red, with Fe levels that contrast markedly with Tío Campano’s, implying distinct ochre sources.

The black-over-white and white-over-black samples, concentrated in Ceja de Piezarrodilla (n = 5) and Cabras Blancas (n = 11), show distinct patterns. Ceja de Piezarrodilla black-over-white samples contain moderate Mn, suggesting Mn-based black pigment beneath the white overlayer. In contrast, Cabras Blancas white-over-black samples show negligible Mn and P, indicating different black pigment technology or more complete coverage by the white overlayer.

Overall, PERMANOVA confirms location as the primary variance driver (

Table 3,

Table 6 and

Table 9), explaining 49%–68% of compositional differences—values indicative of strong geological control tempered by pigment type and technological choices.

4.4. Insights into Pigment Technology and Raw Material Procurement

The pigment-specific discriminators illuminate prehistoric technological repertoires with unexpected complexity. Red pigments uniformly implicate Fe-rich ochres, but substantial inter-shelter Fe variation (

Table S26) suggests exploitation of diverse sources, possibly from local ferricretes, as inferred from similar variability in Cantabrian rock art [

45]. The absence of correlated As or Hg (

Table S1) excludes the use of iron arsenopirite or cinnabar admixtures.

Black pigments reveal a dual technology that transcends shelter boundaries: Mn-oxide-based pigments occur at Ceja de Piezarrodilla, Hoya de Navarejos III, and La Cocinilla del Obispo, versus Mn-absent alternatives found at Hoya de Navarejos IV, Cabras Blancas, Prado Navazo, and remarkably, within the same shelters showing Mn-rich samples (Hoya de Navarejos III and Ceja de Piezarrodilla,

Table S1). This within-shelter coexistence of Mn-rich and Mn-poor blacks represents the clearest evidence for technological diversity. The P association in low-Mn samples, when exceeding substrate baselines (

Table S2), is consistent with bone-derived materials, as P would derive from hydroxyapatite in calcined bone [

46]. However, the identification of bone char based on phosphorus enrichment alone requires explicit consideration of alternative P sources. Substrate-derived phosphorus from accessory apatite minerals in the sandstones cannot be entirely excluded, though the selective enrichment in specific pigment samples rather than uniform distribution argues against substrate as the primary source. Post-depositional contamination from guano represents another possibility, though sampling avoided visibly contaminated areas, and the spatial pattern (P elevation in specific motifs rather than diffuse across panels) favors original pigment composition. Diagenetic phosphorus mobilization from organic matter decomposition typically produces diffuse enrichment rather than the localized patterns observed here.

On balance, the bone-derived materials hypothesis remains the most parsimonious interpretation given: (1) clear P enrichment above substrate baselines, (2) co-enrichment with Ca consistent with hydroxyapatite, (3) ethnographic parallels documenting bone char use in prehistoric contexts, and (4) the functional association with Mn-poor blacks (substitution where manganese oxides are unavailable). Nevertheless, definitive confirmation requires complementary techniques—Raman spectroscopy to identify carbon species and distinguish bone char from vegetal charcoal, or SEM-EDS to detect bone microstructure. Pending such analyses, P-enriched pigments are interpreted as “consistent with possible bone-derived materials” rather than confirmed bone char.

The technological duality within Ceja de Piezarrodilla—encompassing high-Mn mineral blacks, low-Mn carbon-based pigments (possibly including bone char), and the anomalous high-Mn white—indicates either episodic use of different recipes or complex stratigraphic relationships.

This dual black pigment technology parallels findings by Roldán García et al. [

18] at Saltadora (Valltorta gorge, Castellón), where EDXRF analysis on calcareous substrates identified manganese oxides with barium as a trace element in black deer figures, with Mn-Ba correlation suggesting romanechite or hollandite minerals. However, subsequent work at Cova Remigia [

25] and Cingle de la Mola Remigia [

47] identified carbon-based blacks via Raman spectroscopy—charcoal without detectable phosphorus or manganese via EDXRF. The phosphorus enrichment we document in low-Mn blacks at Albarracín is consistent with bone char rather than simple charcoal, potentially representing a third black pigment technology within the Levantine tradition. The fundamental substrate difference (sandstone at Albarracín vs. limestone at Saltadora/Cova Remigia, where calcium dominates all EDXRF spectra) explains why our discrimination patterns differ from those coastal sites.

The exceptional white pigment with 2.108% Mn (Ceja de Piezarrodilla sample 1) warrants special consideration. Possible explanations include sampling of a palimpsest where white was applied over manganese-rich black, with pXRF penetrating both layers, or diagenetic Mn precipitation forming dendrites or coatings subsequently covered by white pigment. The co-occurrence with P (1.010%) suggests a possible association with organic materials.

White pigments generally derive from substrate-like materials, likely aluminosilicate clay minerals or calcitic components (high Al-Si), with no evidence of exotic additives (e.g., Sn, Sb < LOD). The Sr-Si-Mg triad’s perfect covariance confirms natural geological origin rather than deliberate mixing.

4.5. Methodological Considerations, Limitations, and Future Directions

The multivariate pXRF analysis of 102 pigment samples from 11 shelters in the Albarracín Cultural Park reveals systematic geochemical patterns that reflect the complex interplay between substrate geology, pigment composition, and post-depositional processes. While the penetration depth of pXRF (typically 1–5 mm for major elements in siliceous matrices) captures a composite signal from both the thin pigment layer (often <50 μm) and the underlying rock substrate, the resulting datasets enable robust discrimination among shelters and provide unexpected insights into prehistoric technological choices. The centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation and subsequent multivariate analyses (PCA, LDA, HCA) consistently demonstrate large between-shelter variances, with effect sizes (

Tables S9, S17 and S25) that far exceed those typically reported in archaeometric studies of rock art [

48,

49]. The correlation between effect size magnitude and element type—with substrate-derived elements showing the most extreme values—confirms that geological variation drives much of the observed discrimination, though pigment-specific patterns remain detectable as secondary signals.

The CLR approach effectively mitigated compositional constraints, revealing covariant groups (e.g., Sr-Si-Mg) that standard analyses might misattribute. However, the composite signals limit pure recipe reconstruction; future synchrotron μ-XRF or LA-ICP-MS could isolate surface layers [

50]. Small sample sizes for some shelter-color combinations (e.g.,

n = 1 for Hoya de Navarejos V white, La Cocinilla del Obispo black) constrain generalizability, though bootstrap validation (94.1–100.0% accuracy) affirms robustness for adequately sampled locations.

For heritage management, the 92.6%–100% LDA accuracies enable fingerprinting for authentication, particularly valuable for UNESCO-listed Levantine art vulnerable to looting. High diversity at Ceja de Piezarrodilla flags this shelter for priority investigation regarding differential deterioration risks. The variable sulfur distributions—from substrate-derived to localized diagenetic enrichments via Liesegang banding (

Tables S1 and S2)—combined with widespread chlorine presence from atmospheric deposition, underscore the complex deterioration pathways affecting these paintings. While Cl contamination warrants atmospheric monitoring amid climate-driven increases in Saharan dust transport to Iberia [

51], the site-specific sulfur patterns require targeted conservation strategies. These findings advocate integrated geoarchaeometric protocols for prioritizing interventions in similar open-air sites [

52].

The case of Ceja de Piezarrodilla’s black pigment samples 14 and 15 illustrates how differential preservation can generate statistically significant compositional outliers. These samples, from the bovine’s hindquarters, represent the only portion unaffected by whitish biofilm that has progressively covered the figure’s anterior section [

9]. Their chemical distinctiveness likely reflects the purest signal of original pigment composition, while anterior samples yield composite signals from pigment, substrate, and biological overgrowth. This demonstrates that ‘outliers’ in rock art pXRF datasets may paradoxically preserve the most faithful record of original technological choices, with ‘typical’ samples potentially representing degraded or contaminated states. Such preservation-driven chemical variation underscores the importance of integrating taphonomic assessment with geochemical analysis when interpreting compositional patterns.

Several methodological limitations constrain the interpretive scope of this study. First, pXRF provides elemental composition but cannot identify mineral phases; all mineral identifications (pyrolusite, hematite, gypsum, kaolinite-group clays, hydroxyapatite) remain provisional hypotheses based on characteristic elemental associations rather than definitive structural identification. Portable X-ray diffraction (pXRD) would provide the necessary phase identification to validate or refute these interpretations. Second, the composite signal geometry limits recipe reconstruction; while elements clearly enriched above substrate baselines document genuine technological choices, the absolute proportions of pigment versus substrate contributions remain uncertain. Surface-sensitive techniques (confocal Raman microscopy, synchrotron μ-XRF) could provide layer-resolved analysis. Third, the absence of quantitative colorimetry precludes statistical correlation between elemental composition and visual color properties; future studies incorporating spectrophotometric L*a*b* measurements could establish whether subtle compositional variations correlate with perceptible hue differences within color categories. Fourth, carbon-based pigments (charcoal, bone char) are invisible to XRF; Raman spectroscopy is required to identify carbon species and distinguish vegetal charcoal from bone char based on characteristic spectral features. Fifth, small sample sizes for some shelter-color combinations limit the generalizability of conclusions for those specific groups. Sixth, the substrate characterization (n = 9 measurements per shelter) provides representative rather than exhaustive coverage; localized substrate heterogeneity within shelters may contribute additional variance not captured by our sampling design.

These limitations notwithstanding, the systematic patterns documented here provide a robust foundation for targeted follow-up studies. Future research directions include: (1) pXRD for definitive mineral phase identification; (2) Raman spectroscopy for carbon speciation and organic binder identification; (3) quantitative colorimetry combined with elemental/mineralogical data; (4) where conservation permits, targeted micro-sampling for surface-sensitive laboratory techniques providing layer-resolved analysis.

4.6. Implications for Understanding Prehistoric Painting Practices

The extraordinary effect sizes observed (

Tables S11, S19 and S27) represent some of the largest reported in archeological chemistry, indicating that between-shelter variance overwhelmingly dominates within-shelter variance. While this enables excellent site discrimination, it simultaneously suggests that geological overprinting may partially obscure anthropogenic signals. The relationship between effect size and element type provides insight: substrate-derived elements (Ba, Sr-Si-Mg group) yield the most extreme values, while elements clearly associated with intentional pigment use (Fe in red, Mn in black, where intentionally added) show large but less extreme effects.

The technological complexity revealed (particularly the dual black pigment technologies at Ceja de Piezarrodilla and Hoya de Navarejos III) suggests more sophisticated painting practices than previously recognized. The coexistence of manganese-based and carbon-based black pigments within single shelters may reflect diachronic changes in raw material availability or cultural preferences, or work by different artist groups with distinct technological traditions. The black-over-white samples further indicate deliberate layering strategies, though the chemical penetration of pXRF complicates interpretation of intentionality versus superimposition.

The persistence of shelter-specific signatures across different pigment colors, exemplified by Ceja de Piezarrodilla’s consistent heterogeneity and the Casa Forestal complex’s relative homogeneity, confirms that local geology exerts primary control on chemical profiles. However, the documented technological choices (selective use of manganese oxides versus carbon-based materials, variable iron oxide sources, and complex layering) demonstrate that cultural factors significantly modulate these geological baselines.

The compositional heterogeneity observed within individual shelters carries significant archeological implications. At Ceja de Piezarrodilla, the coexistence of Mn-rich black pigments (samples 2, 3, 6: >0.33% Mn) and Mn-poor alternatives (samples 14, 15: <0.2% Mn) within the same decorated panel indicates either: (1) multiple episodic painting events with evolving material preferences over time, (2) parallel workshop traditions with distinct technological knowledge operating contemporaneously, or (3) functional differentiation of pigment types for specific applications. The similar pattern at Hoya de Navarejos III reinforces this interpretation. Conversely, the relative homogeneity at Casa Forestal suggests a more coordinated raw material procurement strategy, possibly reflecting single painting episodes or standardized workshop practices.

The specific enrichment patterns documented (Fe in reds exceeding substrate baselines by factors of 1.5–6×, Mn in specific blacks reaching concentrations 10–20× above detection limits where substrate Mn is consistently <LOD) cannot be attributed to layer thickness variations alone and document genuine technological choices. These findings challenge assumptions about technological homogeneity in Levantine art production and indicate that Albarracín rock art represents sophisticated technological systems rather than opportunistic use of immediately available materials.