Abstract

This review synthesizes the corpus of archaeometric and analytical investigations focused on mortar-based materials, including wall paintings, plasters, and concrete, in the Roman Regio X and neighboring territories of northeastern Italy from the mid-1970s to the present. Organized into three principal categories—wall paintings and pigments, structural and foundational mortars, and flooring preparations—the analysis highlights the main methodological advances and progress in petrographic microscopy, mineralogical analysis, and mechanical testing of ancient mortars. Despite extensive case studies, the review identifies a critical need for systematic, statistically robust, and chronologically anchored datasets to fully reconstruct socio-economic and technological landscapes of this provincial region. This work offers a programmatic research agenda aimed at bridging current gaps and fostering integrated understandings of ancient construction technologies in northern Italy. The full forms of the abbreviations used throughout the text to describe the analytical equipment are provided at the end of the document in the “Abbreviations” section.

1. Introduction

The study of ancient mortars has emerged as a vital discipline in archeology, offering critical insights into the technological capabilities of past civilizations. Through mortar analysis, researchers can reconstruct historical building techniques, establish both relative and absolute chronologies of architectural structures, and determine the provenance and trade routes of raw materials [1]. This interdisciplinary approach not only enhances our understanding of construction practices but also sheds light on broader socio-economic frameworks and cultural interactions.

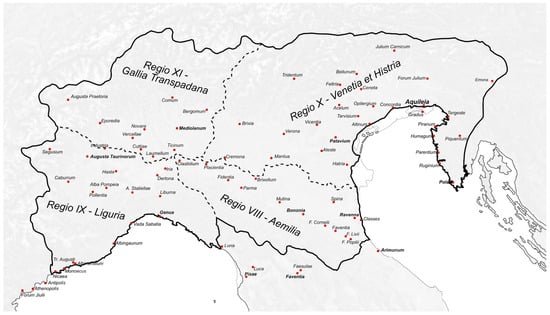

This review aims to present a comprehensive overview of archaeometric studies focused on mortar analysis in northeastern Italy, corresponding approximately to the ancient Roman Regio X—Venetia et Histria and the neighboring territory. In antiquity, this region extended from the modern-day Italian regions of eastern Lombardy to the Venetian Lagoon, comprising the Friuli-Venezia Giulia and most of the Trentino-Alto Adige regions, together with portions of Slovenia and the Istrian Peninsula (Figure 1). Historically, this area has demonstrated a distinctive cultural identity and construction tradition, evident in its masonry, flooring systems, and wall finishes [2,3,4,5,6]. These features also reflect the particular characteristics of mortar-based materials used for construction of decorative purposes, thus offering an overview of the studies conducted on different mortar typologies in what is one of the main “peripheral realities” within the Roman Empire.

Figure 1.

The ancient Roman regions in northern Italy, with the main ancient towns indicated.

Archaeometry of mortar-based materials in northeastern Italy began in the mid-1970s. One of the first studies conducted was the analytical piece of work by L. Kociszewski in 1977, which focused on some Roman and medieval plaster samples (to which were also added fragments of mosaic preparations) found during the excavations on Torcello (the northern lagoon of Venice), conducted by Polish researchers from the University of Warsaw [7]. Eight mortar samples, dated to the Roman period and others dated from the Early Medieval period, were analyzed using Transmitted Light Optical Microscopy (TL-OM) on thin sections and Chemical Dissolution (CD).

Shortly afterward, L. Lazzarini published the results on the analyses on some fragments of Roman plaster found in excavations at the Giardini Eremitani in Padua [8], where pigments and preparatory mortar samples (tectorium) were analyzed using TL-OM on thin sections and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD).

Only ten years later, new archaeometric studies were published, such as those by B. D’Ambrosio and S. Sfrecola on the plasters recovered from the excavations at Milan’s Santa Maria alla Porta, where through stereomicroscope in reflected light numerous wall paintings and stucco samples were analyzed [9,10]. Another study was published by G. Alessandrini and collaborators on the wall painting fragments from the excavations of the imperial villa at Sirmione on Lake Garda [11], analyzed using TL-OM on thin sections.

In can be noted that, between the 1970s and 1990s, research has mainly focused on wall painting fragments, which have been the subject of significantly more analytical and archaeometric studies than other types of mortars, such as structural ones. This is due to both the historical, artistic, and cultural value of Roman painting and the continued interest of the scholarly community.

In the following decades, there has been a noticeable increase in publications specifically focused on mortar-based materials. The available bibliography is mainly composed of a series of case studies, primarily published as appendix in the framework of larger archeological projects, and more rarely as independent research studies. These studies have seldom been incorporated into broader syntheses. However, since the 1990s, research on mortars, plasters, and concretes in the region has started to expand, with growing attention also being paid to mortar-based materials different from wall paintings.

This review is therefore organized into three main categories of mortar-based materials found in this region as follows: (1) wall paintings and pigments, which have the longest research tradition; (2) structural and foundational mortars, which have only recently become a focus of investigation; and (3) floor preparation layers, which remain underrepresented in the literature and are often only addressed within the framework of conservation efforts related to mosaics and site restoration.

2. Archaeometry of Wall Paintings and Pigments

Since the early 1990s, analytical research on Roman wall plasters in northern Italy has been primarily driven by R. Bugini and L. Folli, starting with their pioneering studies on the wall paintings from the western hall of the Republican sanctuary of Brescia/Brixia [12,13]. In the following decades, the Lombardy region (in the western portion related to the ancient Regio IX—Gallia Transpadana) became the primary focus of investigations on Roman wall paintings. Their research gradually expanded to include a wide range of sites across the region, including Cremona, Milan/Mediolanum, Calvatone/Bedriacum, Civitate Camuno, and Desenzano del Garda [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The main adopted techniques adopted include TL-OM on thin sections, XRD and, more recently, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) and Scanning Electron Microscopy-Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) for pigments. To date, this research encompasses more than 150 samples from contexts of varying chronology. To this body of work, two additional studies can be added, detailed as follows: one concerning further analyses of wall paintings from the western hall of the sanctuary in Brescia [25], and the other on new analyses on the fragments from the imperial villa (so-called Grotte di Catullo) in Sirmione on Lake Garda [26].

The increase in the study of wall paintings during the 1990s, though often fragmentary and found in fill layers during archeological excavations, closely mirrors the broader trajectory of Roman wall painting research in northern Italy, which, due to the highly fragmentary nature of the material, has only recently emerged as a fully developed field of study [27,28].

Since the early 2000s, a number of archaeometric studies began to emerge in other areas of northern Italy, particularly in the eastern regions.

In the modern-day Veneto region, a significant leap forward was made thanks to numerous contributions by G.A. Mazzocchin and collaborators from Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, published over the past two decades. The majority of case studies come from the main Roman urban sites in Veneto, such as Vicenza, Verona, Concordia Sagittaria, Montegrotto Terme, Padova, together with minor sites (Rocca di Manerba) [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. In this case, the focus has been on the characteristics of the pigments rather than the preparatory mortars, which have been analyzed primarily using spectroscopic techniques, such as FT-IR and Raman Spectroscopy (Raman), and to a lesser extent, using TL-OM, SEM-EDS, or XRD.

This main group can also include studies conducted at other sites, including the wall paintings from the cryptoporticus of the Capitolium in Verona [37] (pp. 641–642), with a predominantly petrographic approach using OM-TL, and more recently, from Negrar in Valpolicella near Verona [38], adopting multi-analytical methods for the study of both mortars and pigments, via OM-TL, XRD, SEM-EDS, and Raman.

There have been fewer in-depth studies on the analytical characteristics of wall paintings in Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Worth mentioning are two short notes from the early 1990s published in the exhibition catalog Roman Aquileia. Public and Private Life (1991), which reported on petrographic and mineralogical analyses of a small number of wallpainting fragments recovered from Roman houses beneath the medieval baptistery in Aquileia [39,40], and a study of pigments from the wall paintings found in a Roman Villa near Pordenone and Trieste [30]. In recent years, a renewed wave of studies focused primarily on the center of Aquileia has, for the first time, analyzed a significant corpus of wall painting fragments attributed to different archeological periods, ranging from the Late Republican era to the Early Imperial age. By concentrating on the preparatory characteristics of the mortars, as well as pigments, these multi-analytical studies have highlighted important evolutions in wall painting preparation techniques. Such findings can provide valuable clues for potential chronological framing in the absence of other stratigraphic or stylistic data, relying primarily on OM-TL analyses of the mortars and the surface layers of the intonachino [41,42,43,44].

South of Regio X, in the Emilia Romagna region (Regio VII—Aemilia), research has largely been coordinated by P. Baraldi and collaborators, whose work has seen considerable expansion in the past decade. The sites investigated include Bresciello/Brixellum, Cattolica near Rimini, Claterna near Bologna, Castelfranco Emilia near Modena, Faenza/Faventia, Forlì, Modena/Mutina, Montegibbio near Modena, Parma, Piacenza/Placentia, Ravenna, Reggio Emilia, and Rimini/Ariminum [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. A particular case is [53], where the focus shifts to the pigments used for making the preparatory drawing for mosaics. In all the latter cases, the main focus has been on the characteristics of the pigments rather than the preparatory mortars, which have been analyzed coupling TL-OM, SEM–EDS, Raman, and FT–IR, XRD, and Colorimetry. Other techniques such as XRPD, Thermogravimetry and Differential Thermal Analysis (TGA/DTA), and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) were used in other studies.

Beyond Lombardy, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and Emilia, research in the Trentino-Alto Adige region has been more limited, with studies by [54] primarily focused on pigment characterization, and [55,56], who also included plaster layers from Isera.

In Slovenia, plaster fragments from the Roman site of Emona (modern Ljubljana) [57], Celje [58], and villae rusticae near Mošnje and Školarice [59,60,61] have also been analyzed using TL-OM, XRD, SEM-EDS, FT-IR together with Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP).

In summary, older studies tend to focus primarily—or even exclusively—on the painted surfaces, while the petrographic and compositional features of the preparatory layers (tectorium) have only come under closer scrutiny in more recent years. The notable exception to this is the work of R. Bugini, L. Folli, and colleagues, who, since the earliest studies of the 1990s, emphasized the technical aspects of the mortars by investigating the preparatory mortar layers. In recent years, the growing interest in preparatory mortars of ancient Roman wall paintings of the considered territory is also reflected in various contributions addressing the nature and provenance of raw materials, particularly the sands used in preparatory mortars of wall paintings [62], even introducing statistical multivariate methods to manage data from Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) analyses [63], the geological origin and sources of spathic calcite clasts used in intonachino [64,65,66], the characteristics of monocrystalline aggregates [67], and the role of clay in wall painting preparations [68,69,70].

3. Archaeometry of Structural Mortars and Concretes

Interest in the study of structural mortars, compared to that devoted to wall paintings, has been largely neglected until relatively recent years, with most significant contributions emerging only after the 2000s. One of the earliest examples—almost pioneering in nature—is the work of O.-H. Lamprecht, who, in 1984, analyzed a concrete sample from an unspecified structure in the imperial villa at Sirmione [71] (pp. 64–65) using Mechanical Compression Tests (MCT).

From the 1990s to the present, research on bedding and structural mortars has remained extremely limited. Analytical data, often presented as appendices in broader studies on building materials and construction techniques, are generally fragmented and based on isolated case studies, with restricted sampling from individual ancient monuments. Among these are the archaeometric investigations of bedding mortars via XRD in the brick foundations of the Republican walls of Modena [72]. Other examples of analyses on bedding mortars, primarily investigated via TL-OM on thin section and/or XRD, investigated the wall joints of the cryptoporticus of the Capitolium in Verona [37], (pp. 640–641) and the foundational concrete and opus caemeticium of the amphitheaters of Como [73,74] and Padova [75,76]. Wall mortars from various structures were analyzed with the same approach in urban and suburban sites and villas, as those in Desenzano [77], Ravenna [78], Milan [79], Egna-Kahn near Bozen [80], and the Doss Penede sites north of Lake Garda [81]. A vault in opus caementicium from the Republican sanctuary in Brescia was also analyzed [12].

Different from wall and structural mortars, studies of linings, and mortars for hydraulic infrastructures (such as aqueducts and cisterns) are even more limited; [82] studied the linings of Roman aqueducts near Brescia.

A notable leap in this field has occurred since the second decade of the 2000s, with a series of research initiatives led by the University of Padova. In particular, compositional and technological characterizations of mortar-based materials from the theater and amphitheater of ancient Patavium (Padova) have been carried out using advanced archaeometric methods, including TL-OM on thin sections, XRD on bulk mortars and separated binders, SEM-EDS, combined with MCT [83,84,85]. For the first time in the considered region, 14C Radiocarbon Dating and Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) methods were even applied for the dating of mortar samples from Roman and Late Antique buildings of Patavium [84,86]. Analytical investigations made it possible to identify a distinctive type of local volcanic pozzolan, likely sourced from the Euganean Hills volcanic district, used to enhance the mechanical properties of the structural mortars in the buildings under study.

Ongoing investigations, developed with the same approach, have extended to Roman structures and villas from Montegrotto (ancient Fons Aponi) and Mutteron dei Frati in Bibione near Venice (see reports on these sites in [87]). Of particular significance is the discovery of Phlegraean volcanic pozzolans in an underwater Roman construction in the Venice Lagoon, representing the first such evidence for this region of such long trade of imported materials for mortar production ([88], revising preliminary analyses in [89]).

In recent years, special attention has also been directed to Aquileia, a key urban center in Roman northern Italy that had previously been almost entirely overlooked in studies of this kind. The only earlier data came from a few unpublished analyses of mortar samples taken from structures near the river port, conducted by R. Bugini and L. Folli and briefly mentioned in [3] (pp. 36–38) and notes 60,63. More recently, extensive structural analyses have been undertaken on a significant dataset of mortars from Aquileia (over 300 samples), primarily through research initiatives promoted by the University of Padova. These studies have targeted various contexts: structural mortars of the High Imperial theater [90], the amphitheater [91], the Late Antique baths [92,93], and further case studies such as the domus of Tito Macro [94], the Republican Urban walls [94,95,96], the episcopal complex, and riverbank constructions, detailed in a recent monograph [95] and in a report in [87], including reviews focusing on the hydraulic properties of these mortars [96]. Analytical techniques used in this research involve OM-TL on thin sections, XRD on bulk mortars and separated binders, SEM-EDS, and, in certain cases, Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (SS-NMR). Statistical multivariate methods, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), were employed to identify groups of mortars useful for reconstructing building phases, while geochemical techniques like XRF and Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) were used to trace the provenance of imported volcanic pozzolans.

Collectively, this body of research has significantly advanced our understanding of the technological and production-specific features of northern Italian craftsmanship. For the first time, these studies have documented the procurement and the combined use of local and imported volcanic pozzolans in construction, a practice previously undocumented for these geographic and cultural contexts.

Beyond Italy, research has also intensified in recent years. In Slovenia and Croatia, systematic studies have been undertaken, including work on binder mixtures from a rustic villa near Mošnje [59] and Školarice [97], analyzed with multi-analytical procedures including TL-OM, XRD, SEM-EDS, FT-IR, TGA/DTA.

4. Archaeometry of Pavements and Floor Preparations

To conclude, some data should also be mentioned regarding the mortars and concrete used in floor preparation screeds, which have been mostly analyzed within the context of diagnostics aimed at guiding conservation and restoration interventions on ancient mosaics and sectilia. A few examples can be found in the literature (e.g., [98,99,100,101]). Only a few samples were analyzed using TL-OM, mainly for diagnostic purposes aimed at guiding restoration interventions.

On the other hand, few studies have focused specifically on the analysis of floor preparation layers with the goal of gaining a deeper understanding of ancient construction techniques in this sector of construction. Relevant case studies include the analyses of mosaics from Faenza [102], Montegrotto near Padova [103], Montegibbio near Modena [47,50], and Mosnje and Školarice in Slovenia [59,60,97]. As observed for wall plasters, an important core of work has been carried out through the research of R. Bugini and L. Folli, primarily focused on sites in Lombardy, including Brescia [104], Cremona [105], Desenzano del Garda [77], Milan [79,106]. A synthesis of the characteristics of preparatory layers of Roman mosaics in Lombardy is offered in [107,108]. A single study was dedicated to mosaic preparations in Aquileia [109].

The analyses by the authors primarily relied on TL-OM of thin sections, aiming to identify and distinguish the number and composition of the preparatory layers of the floors, mainly mosaics, that were studied. In more comprehensive works, efforts have been made to compare analytical data with references in Latin technical literature—particularly the writings of Vitruvius and Pliny—on floor making techniques [106,108,109]. In some cases, the analyses have enabled scholars to reconstruct aspects of workforce organization on construction sites and to delineate construction phases based on compositional similarities in the materials used for floor bedding layers ([102], especially p. 311; [103] (pp. 430–432)).

More recently, comprehensive diachronic studies, promoted by the University of Padova on the already mentioned site of Aquileia, have highlighted important shifts in the preparatory traditions of ancient pavements, in particular mosaics, over time. As well as wall paintings, these studies have proven valuable in offering chronological insights into ancient floor constructions offering tools for dating the pavements based on the making technique [91,110,111].

However, the overview presented here shows that in Regio X and northern Italy, the archaeometric study and characterization of mortar-based materials used in floor preparation remains limited, with most attention directed toward mosaics. For other types of pavements, archaeometric research is still significantly underdeveloped.

5. Conclusive Remarks

From the perspective of analytical techniques and the depth of investigation, it is evident that, particularly in past decades, the study of wallpaintings, and especially of pigments, received the most attention. This is reflected not only in the higher number of case studies examined, but also in the array of techniques employed, which frequently included spectroscopic and chemical instrumentation aimed at material analysis. In contrast, the study of samples from structural, hydraulic, or flooring preparation mortars saw more limited sampling and a characterization process primarily based on petrographic techniques (TL-OM), sometimes supported by mineralogical analyses such as XRD. Only in more recent years, especially the most recent, a significant deepening in the study of structural mortars has been observed (Table 1). This shift has involved the adoption of chemical, microchemical, and high-resolution geochemical techniques aimed at a more precise understanding of production technology and the provenance of raw materials. There has also been growing interest in analytical methods for material dating.

Table 1.

Summary table of the cases mentioned in the text.

Under a diachronic perspective, the state-of-the-art overview presented here demonstrates how interest in the mortar-based materials used in antiquity within Regio X and the surrounding territories has grown significantly only over the past two decades, in parallel with the development of new and increasingly meticulous investigative protocols. Research directions are diverse and may take a technical-typological approach (examining characteristics of pozzolanic mortars, plasters, and pigments, as well as types of raw materials employed), a contextual-functional approach (using mortar analysis to distinguish construction phases), or a geographical-territorial focus (analyzing local technical traditions or raw material procurement zones). While early investigations were often relegated to appendices of archeological reports tied to systematic excavations, more recent studies have gained autonomy as independent scientific works. These are frequently multi-analytical in nature and often include the analysis of significant datasets, offering a more coherent and comprehensive picture of ancient technologies, construction traditions, and the provenance of raw materials. However, few systematic studies have been carried out to investigate the distribution, chronology, and functional characteristics of a large statistical sample of mortar-based materials within the clearly defined spatial context of a single ancient urban center [95]. This approach allows for a meaningful contextualization of findings within the broader social, economic, and artisanal landscape. Recent analytical syntheses, such as those by R. Bugini with L. Folli and collaborators, or by P. Baraldi and collaborators, based primarily on wall painting samples from sites in Lombardy and Emilia, constitute significant contributions in this direction (e.g., [20,26,49]). Along the same lines are several diachronic studies focusing on mosaics from the Lombardy area, previously mentioned [105,107,108].

However, these latter studies, although certainly commendable for providing a fundamental summary of the current state of research on the specific topics, were developed retrospectively, compiling data from analyses conducted over many years rather than from a programmatic research plan. As a result, sometimes key aspects are missing, like the diachronic dimension, that in many cases remains limited; for example, many of the samples come from undated contexts or lack representation from the middle to late Imperial period. Thus, for Northern Italy, there is a clear need for comprehensive syntheses and programmatic projects that integrate the scattered data from years of research with a specific task that will enable for broader historical and socio-economic interpretations. Only through the intensive, multifaceted investigation of a single or multiple ancient center can we hope to achieve a statistically robust and diachronically complete understanding of mortar-based production techniques and tradition within a specific region. This is the scope driven by the present study, which aims to establish a reliable foundation for reconstructing the technological evolution of mortar-based materials in key urban sites of Roman Regio X and neighboring territories.

In light of these considerations, it is to be hoped that future research will increasingly adopt interdisciplinary and systematic approaches, capable of integrating high-resolution archaeometric analyses with a solid historical, functional, and territorial understanding of archeological contexts. Only through targeted investigations, based on statistically significant datasets and clearly defined chronological frameworks, can the current fragmentation of data be overcome, enabling a more comprehensive reconstruction of the technological evolution of mortars in relation to the socio-economic and cultural dynamics of ancient urban centers. This perspective opens a promising and innovative research path, not only for the specific geographical and chronological context considered, but more broadly within the overall landscape of studies on ancient construction materials. Such a methodological direction has the potential to provide more robust and comparable interpretive tools, significantly advancing the discipline on a global scale.

Funding

This research was financed from the project Trade and Use of Volcanic Pozzolans in the Roman World: A Natural Material for the Production of Eco-Sustainable Concrete of Antiquity (Principal investigator: Simone Dilaria, BIRD 2023—Integrated Budget for the Departmental Research of the Department of Cultural Heritage of the University of Padova; project code BIRD230232/23).

Data Availability Statement

The data other than those reported in the text are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations for analytical techniques are adopted in this manuscript:

| CD | Chemical Dissolution |

| DRIFTS | Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GR | Granulometry |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| (LA)ICP-MS | (Laser-Ablation) Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| MIP | Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry |

| MCT | Mechanical Compression Test |

| OSL | Optically Stimulated Luminescence |

| Raman | Raman Spectroscopy |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning Electron Microscopy-Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy |

| SS-NMR | Solid State-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| TGA/DTA | Thermogravimetry and Differential Thermal Analysis |

| TL-OM | Transmitted Light Optical Microscopy |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction/Powder Diffraction |

| XRF | X-Ray Fluorescence |

References

- Gliozzo, E.; Pizzo, A.; La Russa, M.F. Mortars, plasters and pigments—Research questions and sampling criteria. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, A. Edilizia Rurale Romana. Materiali e Tecniche Costruttive Nella Pianura Padana (II sec. a.C.–IV sec. d.C.); Flos Italiae, Documenti di archeologia della Cisalpina Romana, 4; All’insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Portulano, B.; Urban, M. Materiali e Tecniche Murarie nel Basso e Medio Friuli in Età Romana; Varie dal passato 3; Editreg: Trieste, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Previato, C. Aquileia. Materiali, Forme e Sistemi Costruttivi Dall’età Repubblicana Alla Tarda Età; Antenor Quaderni, 32; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Didonè, A. Pittura Romana Nella Regio X. Contesti e Sistemi Decorativi; Antenor Quaderni, 49; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ghedini, F.; Bueno, M.; Novello, M.; Rinaldi, F. (Eds.) I Pavimenti Romani di Aquileia. Contesti, Tecniche, Repertorio Decorativo; Antenor Quaderni, 37, 1–2; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kociszewski, L. Esami fisico chimici dei campioni delle malte di Torcello. In Torcello, Scavi 1961–1962; Leciejewicz, L., Tabaczyńska, E., Tabaczyński, S., Eds.; Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte Monografie, III; Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte: Rome, Italy, 1977; pp. 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini, L. Analisi chimico mineralogiche su alcuni frammenti di affresco romano da piazza Eremitani in Padova. Archeol. Veneta 1978, 1, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, B.; Sfrecola, S. Intonaci dipinti: Analisi applicate ai materiali. In Santa Maria Alla Porta: Uno Scavo nel Centro Storico di Milano; Cerasa Mori, A., Ed.; Studi Archeologici, 5; Istituto universitario di Bergamo: Bergamo, Italy, 1986; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, B.; Sfrecola, S. Stucchi: Analisi mineralogico petrografiche. In Santa Maria Alla Porta: Uno Scavo nel Centro Storico di Milano; Cerasa Mori, A., Ed.; Studi Archeologici, 5; Istituto universitario di Bergamo: Bergamo, Italy, 1986; p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini, G.; Bolla, M.; Bugini, R.; Roffia, E. Characterization of plasters from the Roman Villa of Sirmione (Brescia–Italy). In Role of Chemistry in Archaeology, Proceedings of the 1st International Colloquium, Hyderabad, India, 15–18 September 1991; Ganorkar, M.C., Rama Rao, N., Eds.; Birla Institute of Scientific Research: Hyderabad, India, 1992; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Santuario repubblicano, aula occidentale: Analisi dei materiali lapidei e dei prodotti di degrado. In Carta Archeologica Della Lombardia, V Brescia. la Città; Rossi, F., Ed.; Franco Cosimo Panini: Modena, Italy, 1996; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Materials and Making Techniques of Roman Republican Wall Paintings (Capitolium, Brescia, Italy). In Roman Wall Painting. Materials, Techniques, Analysis and Conservation, Proceedings of the International Workshop, Fribourg, Switzerland, 7–9 March 1996; Bearat, H., Fuchs, M., Maggetti, M., Paunier, D., Eds.; University of Fribourg: Fribourg, Switzerland, 1997; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Brescia. Via Musei, casa Pallaveri. Indagini tecniche sui materiali del santuario tardorepubblicano. Notiziario Della Soprintendenza Archeologica. Della Lombardia, 1992–1993 1996, 1992–1993, 105–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Confronto di intonaci romani in area lombarda. In Atti del II Congresso Nazionale di Archeometria; Bologna, 29 January–1 February 2002; D’Amico, C., Ed.; Pàtron: Bologna, Italy, 2002; pp. 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Indagini scientifiche sugli intonaci romani. In Dalle Domus Alla Corte Regia. S. Giulia di Brescia. Gli Scavi dal 1980 al 1992; Brogiolo, G.P., Morandini, F., Rossi, F., Eds.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2005; pp. 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Il santuario romano. Caratteristiche degli intonaci e degli strati pittorici. In Il Santuario di Minerva. Un Luogo di Culto a Breno tra Protostoria ed età Romana; Rossi, F., Ed.; Arbor Sapientiae: Milan, Italy, 2010; pp. 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Critères pour la comparaison des enduits peints romains de la Lombardie. ArcheoSciences 2013, 37, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Materiali da costruzione e metodologia di messa in opera nel santuario repubblicano di Brescia. In Un Luogo per gli dei. L’area del Capitolium di Brescia; Rossi, F., Ed.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2014; pp. 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Vaudan, D. Les pigments vert et rouge d’une peinture murale d’époque romaine républicaine (Brescia, Italie). In Art et Chimie, la Couleur, Proceedings of the Actes du Congrès, Paris, France, 15 September 1998; Goupy, J., Mohen, J., Eds.; CNRS: Paris, Italy, 2000; pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R. Composizione degli intonaci. In L’area Archeologica del Monastero Maggiore di Milano: Una Nuova Lettura Alla luce Delle Recenti Indagini; Blockley, P., Cecchini, N., Pagani, C., Eds.; Quaderni del Civico Museo Archeologico di Milano, 4; Civico Museo Archeologico: Milan, Italy, 2012; pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Ceresa Mori, A.; Folli, L.; Pagani, C. Relationship between plaster coats in Roman wall paintings (Milan Italy). In Antike Malerei Zwischen Lokalstil und Zeitstil, Akten des XI. Internationalen Kolloquiums der Aipma—Association Internationale Pour la Peinture Murale Antique; Ephesos, 13–17 September 2010; Zimmermann, N., Ed.; Austrian Academy of Sciences: Vienna, Austria, 2014; pp. 543–549. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Mariani, E.; Pitcher, L. Features of Roman ceiling plasters from Cremona (Italy). In ISA 2012, Proceedings of the 39th International Symposium on Archaeometry, Leuven, Belgium, 28 May–1 June 2012; Scott, R.B., Braekmans, D., Carremans, M., Degryse, P., Eds.; Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 2014; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Mariani, E.; Pagani, C. Pigment composition and applying methods in Roman wall painting of Lombardy (2nd Century BCE–4th Century CE). In Context and Meaning, Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference of the Association Internationale pour la Peinture Murale Antique, Athens, Greece, 16–20 September 2010; Moormann, E.M., Mol, S.T.A.M., Eds.; Babesch Supplements, 31; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2017; pp. 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Meucci, C. Analisi degli strati pittorici di frammenti di intonaci dipinti. In Nuove Ricerche sul Capitolium di Brescia. Scavi, Studi e Restauri; Rossi, F., Ed.; ET: Milan, Italy, 2002; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Roffia, E.; Bugini, R.; Biondelli, D.; Folli, L. Le pitture murali della villa romana detta “Le Grotte di Catullo” (Sirmione). In Sulle Pitture Murali. Riflessioni, Conoscenze, Interventi, Proceedings of the Conference, Bressanone, Italy, 12–15 July 2005; Biscontin, G., Driussi, G., Eds.; Scienza e Beni Culturali, Vol. XXI; Arcadia: Venezia, Italy, 2005; pp. 755–761. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori, M.; Scagliarini, D. (Eds.) TECT 1. Un Progetto per la Conoscenza Della Pittura Parietale Romana Nell’Italia Settentrionale; Antenor Quaderni, 34; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori, M.; Scagliarini, D.; Didonè, A.; Helg, R.; Malgieri, A.; Salvo, G.; Coralini, A. (Eds.) TECT 2. La Pittura Frammentaria di età Romana: Metodi di Catalogazione e Studio dei Reperti; Atti della giornata di studio (Padova, 20 March 2014); Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Agnoli, F.; Mazzocchin, S.; Colpo, I. Analysis of pigments from Roman wall paintings found in Vicenza. Talanta 2003, 61, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Agnoli, F.; Salvadori, M. Analysis of Roman age wall paintings found in Pordenone, Trieste and Montegrotto. Talanta 2004, 64, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Rudello, D.; Murgia, E. Analysis of Roman wall paintings found in Verona. Ann. Chim. 2007, 97, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Del Favero, M.; Tasca, G. Analysis of pigments from Roman wall paintings found in the “Agro Centuriato” of Julia Concordia (Italy). Ann. Chim. 2007, 97, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Baraldi, P.; Barbante, C. Isotopic analysis of lead present in the cinnabar of Roman wall paintings from the Xth Regio “Venetia et Histria” by ICP MS. Talanta 2008, 74, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Vianello, A.; Minghelli, S.; Rudello, D. Analysis of Roman wall paintings from the thermae of “Iulia Concordia”. Archaeometry 2010, 52, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; Mazzocchin, S.; Rudello, D. Analisi dei pigmenti e degli strati preparatori di pitture parietali romane provenienti da Padova. Archeol. Veneta 2011, XXXIII/2010, 176–191. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchin, G.A.; De Lorenzi Pezzolo, A.; Vianello, A. Spectroscopic analysis of wall paintings from Rocca Manerba. Sci. Cà Foscari 2013, 2, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- De Vecchi, G. Analisi delle pietre e dei materiali edilizi. In L’area del Capitolium di Verona: Ricerche Storiche e Archeologiche; Cavalieri Manasse, G., Ed.; Arbor Sapientiae: Verona, Italy, 2008; pp. 637–643. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Sbrolli, C.; Mosimann, F.S.; Favero, A.; Secco, M.; Santello, L.; Salvadori, M. Production technique and multi analytical characterization of a paint plastered ceiling from the Late Antique villa of Negrar (Verona, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallecchi, P. Caratteristiche composizionali. In Aquileia Romana. Vita Pubblica e Privata; Catalogo della mostra (Aquileia, 07/1991–11/1991); Verzár-Bass, M., Ed.; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 1991; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Turco, R. La tecnica esecutiva degli intonaci dipinti. In Aquileia Romana. Vita Pubblica e Privata; Verzár-Bass, M., Ed.; Catalogo della mostra (Aquileia, 07/1991–11/1991); Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 1991; pp. 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Sbrolli, C. I frammenti di intonaco dipinto. In L’anfiteatro di Aquileia. Ricerche D’archivio e Nuove Indagini di Scavo; Scavi di Aquileia V; Basso, P., Ed.; SAP Libri: Quingentole, Italy, 2018; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, L.; Dilaria, S.; Salvadori, M.; Secco, M.; Oriolo, F.; Artioli, G.; Addis, A.; Rubinich, M. Tectoria e pigmenti nella pittura tardoantica di Aquileia: Uno studio archeometrico. In Nuovi Dati per la Conoscenza Della Pittura Antica, Proceedings of the Atti del I colloquio AIRPA—Associazione Italiana Ricerche e Pittura Antica, Aquileia, Italy, 16–17 June 2017; Salvadori, M., Fagioli, F., Sbrolli, C., Eds.; AIRPA, 1; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Sebastiani, L.; Salvadori, M.; Secco, M.; Oriolo, F.; Artioli, G. Caratteristiche dei pigmenti e dei tectoria ad Aquileia: Un approccio archeometrico per lo studio di frammenti di intonaco provenienti da scavi di contesti residenziali aquileiesi (II sec. a.C.–V sec. d.C.). In La Peinture Murale Antique Méthodes et Apports D’une Approche Technique; Louvain la Neuve, 21 April 2017; Cavalieri, M., Tomassini, P., Eds.; AIRPA, 3; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2021; pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S. La tecnica dell’affresco romano ad Aquileia: Un preliminare confronto tra la fonte vitruviana e il dato archeologico. In Pittura, Luce, Colore. Atti del IV Colloquio dell’Associazione Italiana Ricerche Pittura Antica; Urbino, 17–19 June 2021; Santucci, A., Ed.; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2023; pp. 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi, P.; Bonazzi, A.; Giordani, N.; Paccagnella, F.; Zannini, P. Analytical characterization of Roman plasters of the “domus Farini” in Modena. Archaeometry 2006, 48, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, P.; Baraldi, C.; Curina, R.; Tassi, L.; Zannini, P. A micro-Raman archaeometric approach to Roman wall paintings. Vib. Spectrosc. 2007, 43, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, P. I materiali e le tecniche decorative della villa urbana rustica di Montegibbio. In L’Insediamento di Montegibbio. Una ricerca Interdisciplinare per L’archeologia; Sassuolo, 7 February 2009; Guandalini, F., Labate, D., Eds.; Quaderni di Archeologia dell’Emilia Romagna, 26; All’Insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2010; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi, P.; Zannini, P.; Guandalini, F.; Ferrari, G. Indagini archeometriche su pitture murali dall’insediamento di Montegibbio. In Atti del VII Congresso Nazionale di Archeometria; Modena, 22–24 February 2012; Vezzalini, G., Zannini, P., Eds.; Pàtron: Bologna, Italy, 2012; pp. 980–988. [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi, P.; Tassi, L.; Zannini, P.; Baraldi, C.; Ferrari, G. Da Placentia ad Ariminum. Tecniche e materiali della pittura murale romana nelle domus della Octava Regio. Sci. Dell’antichità 2019, 25, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lugli, S.; Levi, S.T.; Nardelli, E.; Marchetti Dori, S. Dai mosaici agli intonaci: Caratteristiche e provenienza dei materiali da costruzione e delle ceramiche dell’abitato romano di Montegibbio. In L’insediamento di Montegibbio: Una Ricerca Interdisciplinare per L’archeologia; Sassuolo, 7 February 2009; Guandalini, F., Labate, D., Eds.; Quaderni di Archeologia dell’Emilia Romagna, 26; All’Insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2010; pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lugli, G.E.; Tirelli, G.; Baraldi, P.; Lugli, S. Picta fragmenta. Archeometria della pittura parietale da Mutina e territorio. In Nuovi Dati per la Conoscenza della Pittura Antica, Proceedings of the Atti del I Colloquio AIRPA, Aquileia, Italy, 16–17 June 2017; Salvadori, M., Fagioli, F., Sbrolli, C., Eds.; AIRPA, 1; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nannini, M.; Baraldi, P.; Zannini, P.; Stoppioni, L. Indagini Archeometriche su lacerti di pittura murale da Cattolica (Rimini). In Atti del VII Congresso Nazionale di Archeometria; Modena, 22–24 February 2012; Vezzalini, G., Zannini, P., Eds.; Pàtron: Bologna, Italy, 2012; pp. 1002–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi, P.; Bracci, S.; Cristoferi, E.; Fiorentino, S.; Vandini, M.; Venturi, E. Pigment characterization of drawings and painted layers under 5th–7th centuries wall mosaics from Ravenna (Italy). J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 21, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghelli, S.; Baraldi, P.; Zannini, P.; Guaitoli, M.T. Analyses of Roman wall paintings, Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Trento. In Atti del VII Congresso Nazionale di Archeometria; Modena, 22–24 February 2012; Vezzalini, G., Zannini, P., Eds.; Pàtron: Bologna, Italy, 2012; pp. 989–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Finotti, F.; Zandonai, F. I colori degli affreschi della Villa Romana di Isera. Ann. Museo Civ. Rovereto Sez. Archeol. Storia Sci. Nat. 2006, 21, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, P.; Canali, M.; Maurina, B. Archaeometric Characterization of Wall Paintings from Isera and Ventotene Roman Villas. Heritage 2022, 5, 3316–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, M.; Lesar Kikelj, M.; Zupanek, B.; Kramar, S. Wall paintings from the Roman Emona (Ljubljana, Slovenia): Characterization of mortar layers and pigments. Archaeometry 2016, 58, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, M.; Lesar Kikelj, M.; Kuret, J.; Kramar, S. Mortar type identification for the reconstruction purposes of the fragmented Roman wall paintings (Celje, Slovenia). Mater. Technol. 2015, 49, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, S.; Lux, J.; Mirtič, B. Analysis of selected samples of mortars and other construction materials from Object 2 of the Roman villa near Mošnje. Varst. Spomenikov 2008, 44, 190–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kramar, S.; Zalar, V.; Urosevic, M.; Körner, W.; Mauko, A.; Mirtič, B.; Lux, J.; Mladenović, A. Mineralogical and microstructural studies of mortars from the bath complex of the Roman villa rustica near Mošnje (Slovenia). Mater. Charact. 2011, 62, 1042–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, M.; Zanier, K.; Lux, J.; Kramar, S. Pigment analysis of Roman wall paintings from two villae rusticae in Slovenia. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2016, 16, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, N.; Mazzocchin, G.A. The provenance of sand in mortars from Roman villas in NE Italy: A chemical mineralogical approach. Open Miner. J. 2009, 3, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzi Pezzolo, A.; Colombi, M.; Mazzocchin, G.A. Where did Roman masons get their material from? A preliminary DRIFTS/PCA investigation on mortar aggregates from X Regio buildings in Veneto area (NE Italy). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 28798–28807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Calcite crystals as mortar aggregate in northern Italy. In Proceedings of the 11th Meeting of the European Union of Geosciences, Strasbourg, France, 8–12 April 2001; Strasbourg Scientific Research: Strasbourg, France, 2001; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Ubicazione delle cave di pietra da calce utilizzata come materia prima degli intonaci romani nella Lombardia occidentale. Arqueología de la Arquitectura 2016, 13, e049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilaria, S.; Salvadori, M. Marmo e calcite spatica nell’intonaco aquileiese. In Pareti Dipinte. Dallo Scavo Alla Valorizzazione, Proceedings of the Atti del XIV Convegno internazionale AIPMA, Napoli, Italy, 9–13 September 2019; Coralini, A., Giulierini, P., Sampaolo, V., Sirano, F., Eds.; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2024; pp. 557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Monomineralic aggregates in mortars: Examples from Lombardy (Northern Italy). In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress for Applied Mineralogy, Trondheim, Norway, 1–5 August 2011; Broekmans, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Rampazzi, L. Argille negli intonaci di rivestimento parietale. In Un Luogo per gli Dei. L’area del Capitolium di Brescia; Rossi, F., Ed.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2014; pp. 285–286. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Corti, C.; Folli, L.; Rampazzi, L. Unveiling the use of Creta in Roman plasters: Analysis of clay wall paintings from Brixia (Italy). Archaeometry 2017, 59, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugini, R.; Corti, C.; Folli, L.; Rampazzi, L. Roman wall paintings: Characterisation of plaster coats made of clay mud. Heritage 2021, 4, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, H.-O. Opus Caementitium. Bautechnik der Römer, 1st ed.; Beton-Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, U.; Gotti, E.; Tognon, G. Nota tecnica: Malte prelevate da mura antiche dallo scavo della Banca Popolare di Ravenna. In Fortificazioni antiche in Italia. Età repubblicana; Atlante tematico di topografia antica, 9/2000; Quilici, L., Quilici Gigli, S., Eds.; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Roma, Italy, 2001; pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Studio petrografico di malte e pietre. In Novum Comum 2050, Proceedings of the Atti del Convegno Celebrativo Della Fondazione di Como Romana, Como, Italy, 8–9 November 1991; Luraschi, G., Ed.; Società Archeologica Comense: Como, Italy, 1993; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Studio petrografico di malte e pietre dell’edificio romano di via Vitani. In Carta Archeologica Della Lombardia, III. Como. La Città Murata e la Convalle; Uboldi, M., Ed.; Franco Cosimo Panini: Modena, Italy, 1993; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Biscontin, G.; Bakolas, A.; Zendri, E.; Zancanaro, D. Studio di tecnologie delle malte dell’Arena di Padova. In Dal Sito Archeologico All’archeologia del Costruito. Conoscenza, Progetto e Conservazione; Bressanone, 3–6 July 1996; Biscontin, G., Driussi, G., Eds.; Scienza e Beni Culturali, XII; Arcadia Ricerche: Padova, Italy, 1996; pp. 613–623. [Google Scholar]

- Baccelle Scudeler, L.; De Vecchi, G. Tessitura e composizione degli aggregati presenti nella malta dell’opus caementicium nell’anfiteatro romano di Padova. In Gli Edifici per Spettacoli Nell’italia Romana, I; Tosi, G., Ed.; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2003; pp. 961–968. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Le malte. In Dalla Villa Romana All’abitato Altomedievale. Scavi Archeologici in Località Faustinella S. Cipriano a Desenzano; Roffia, E., Ed.; ET: Milan, Italy, 2007; pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Marrocchino, E.; Telloli, C.; Novara, P.; Vaccaro, C. Petro archaeometric characterization of historical mortars in the city of Ravenna (Italy). In Proceeding of the IMEKO TC 4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Trento, Italy, 22–24 October 2020; Athena SrL: Vicenza, Italy, 2020; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Milano, Via Birsa, scavi del 1959 (Via Birsa 1959). Le malte. In L’area Archeologica di Via Birsa. Un Quartiere del Palazzo Imperiale Alla luce Delle Recenti Indagini; Fedeli, A.M., Pagani, C., Eds.; Quaderni del Civico Museo Archeologico e del Civico Gabinetto Numismatico di Milano, 5; Silvana editore: Milan, Italy, 2016; pp. 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, C. Analisi delle malte del sito archeologico di Egna Kahn. In Archäologie der Römerzeit in Südtirol. Beiträge und Forschungen, Archeologia Romana in Alto Adige. Studi e Contributi; dal Ri, L., di Stefano, S., Eds.; Verlag: Bolzano, Italy, 2002; pp. 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mattuzzi, I.; Matteazzi, M. Analisi archeometriche su campioni di malta da Area 1000, Progetto Doss Penede. In Archeologia di un Insediamento D’Altura Nell’Area Altogardesana (Nago Torbole, TN) tra Protostoria ed età Romana; Scavi e ricerche 2019–2021; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2022; pp. 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Analisi scientifiche sulle malte. In Antichi Acquedotti del Territorio Bresciano; Botturi, G., Pareccini, R., Eds.; ET: Milan, Italy, 1991; pp. 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetto, J.; Pettenò, E.; Previato, C.; Trivisonno, F.; Veronese, F.; Volpin, M. Il teatro romano di Padova. Orizzonti. Rassegna Di Archeologia 2021, XXII, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanová, P.; Vedovetto, P.; Dilaria, S.; Secco, M.; Ricci, G.; Brogiolo, G.P. The Late Antique Suburban Complex of Santa Giustina in Padua (North Italy): New Datings and New Interpretations of Some Architectural Elements. Hortus Artium Mediev. 2023, 28, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, J.; Previato, C.; Secco, M. Il teatro romano di Padova. In Architetture e Sistemi Costruttivi dei Teatri e Degli Anfiteatri Antichi in Area Adriatica, Proceedings of the Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Padova, Italy, 14–15 December 2023; Bonetto, J., Ghiotto, A.R., Marchet, B., Eds.; Costruire nel Mondo Antico, 9—Archeologia delle Città Adriatiche, 1; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2025; pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M.; Polymeris, G.S.; Panzeri, L.; Tsoutsoumanos, E.; Ricci, G.; Secco, M.; Martini, M.; Artioli, G.; Dilaria, S.; Galli, A. Analysis Probes and Statistical Parameters Affecting the OSL Ages of Mortar Samples; A Case Study from Italy. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 214, 111298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, J., Previato, C., Dilaria, S., Eds.; Costruire nel mondo antico 11. In Proceedings of the 7th Historic Mortars Conference (HMC 2025), International Conference, Padova, Italy, 2–4 September 2025; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Ricci, G.; Secco, M.; Beltrame, C.; Costa, E.; Giovanardi, T.; Bonetto, J.; Artioli, G. Vitruvian binders in Venice: First evidence of Phlegraean pozzolans in an underwater Roman construction in the Venice Lagoon. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrame, C.; Medas, S.; Mozzi, P.; Ricci, G. Roman ‘Well-cisterns’, Navigational Routes, and Landscape Modifications in the Venice Lagoon and Northeastern Adriatic. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2023, 52, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilaria, S.; Ghiotto, A.R.; Secco, M.; Furlan, G.; Giovanardi, T.; Zorzi, F.; Bonetto, J. Early exploitation of Neapolitan pozzolan (pulvis puteolana) in the Roman theatre of Aquileia, Northern Italy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilaria, S.; Secco, M. Analisi archeometriche sulle miscele leganti (malte e calcestruzzi). In L’anfiteatro di Aquileia. Ricerche D’archivio e Nuove Indagini di Scavo; SAP libri: Quingentole, Italy, 2018; pp. 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Secco, M.; Rubinich, M.; Bonetto, J.; Artioli, G. High-performing mortar-based materials from the Late Imperial baths of Aquileia: An outstanding example of Roman building tradition in Northern Italy. Geoarchaeology 2022, 37, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinich, M.; Bonetto, J.; Cadario, M.; Dilaria, S.; Martinelli, N. Le ‘Grandi Terme’ di Aquileia: Nuovi dati dai sondaggi geognostici sui metodi costruttivi e sulla cronologia di costruzione. Orizzonti 2024, XXV, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilaria, S. Le miscele leganti: Malte e calcestruzzi. In Aquileia. Fondi Cossar. 2. La Domus di Tito Macro e le Mura. 2.1 L’età Repubblicana e Imperiale; Bonetto, J., Furlan, G., Previato, C., Eds.; Scavi di Aquileia II; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2023; pp. 566–585. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S. Archeologia e Archeometria Delle Miscele Leganti di Aquileia Romana e Tardoantica (II sec. a.C.–VI sec. d.C.); Costruire nel mondo antico, 8; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Secco, M.; Bonetto, J.; Ricci, G.; Artioli, G. Making ancient mortars hydraulic: How to parametrize type and crystallinity of reaction products in different recipes. In Conservation and Restoration of Historic Mortars and Masonry Structures; HMC 2022; RILEM Bookseries 42; Bokan Bosiljkov, V., Padovnik, A., Turk, T., Eds.; Rilem: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baragona, A.J.; Zanier, K.; Franková, D.; Anghelone, M.; Weber, J. Archaeometric Analysis of Mortars from the Roman Villa Rustica at Školarice (Slovenia). Ann. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2022, 32, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, C.; Donati, F.; Mambelli, R.; Racagni, P. Studio della struttura e dei materiali presenti nei vari strati di due pavimenti musivi nella zona archeologica di Ravenna. In Mosaico e restauro musivo; Fiori, C., Mambelli, R., Eds.; C.N.R.: Faenza, Italy, 1988; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, C. Analisi dei materiali dell’Asaroton Oecon di Aquileia. In Il Mosaico ‘Non Spazzato’. Studio e Restauro Dell’Asaroton di Aquileia; Nel cuore del mosaico, 3; Edizioni del Girasole: Ravenna, Italy, 2012; pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Clementini, M.; Maioli, M.G.; Carbonara, E.; Macchiarola, M. Piazza Ferrari a Rimini: Il mosaico del triclinio nella “Domus del Chirurgo”. Un intervento tra restauro e manutenzione. In Atti del XV Colloquio dell’Associazione Nazionale per lo Studio e la Conservazione del Mosaico; Aquileia, 4–7 February 2009; Angelelli, C., Salvetti, C., Eds.; AISCOM: Tivoli, Italy, 2010; pp. 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnini, A.; Fratini, F.; Galeotti, M.; Marchesi, M.; Martinelli, C.; Porcinai, S. Restauro, analisi e musealizzazione di una porzione di mosaico di età augustea da Bononia. In Atti del XX Colloquio dell’Associazione Nazionale per lo Studio e la Conservazione del Mosaico; Roma, 19–22 March 2014; Angelelli, C., Paribeni, C., Eds.; AISCOM: Tivoli, Italy, 2015; pp. 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri, C. I mosaici della domus di Palazzo Pasolini a Faenza. In Atti del III Colloquio dell’Associazione Nazionale per lo Studio e la Conservazione del Mosaico; Bordighera, 6–10 December 1995; Guidobaldi, F., Guidobaldi, A.G., Eds.; AISCOM: Bordighera, Italy, 1996; pp. 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Maritan, L.; Mazzoli, C.; Pompermaier, A.; Basso, P.; Zanovello, P. Le malte dei pavimenti di età imperiale del complesso di Via Neroniana (Montegrotto Terme a Padova): Indagini preliminari. In Innovazioni Tecnologiche per i Beni Culturali in Italia; Caserta, 16–18 February 2005; D’Amico, C., Ed.; Pàtron: Bologna, Italy, 2006; pp. 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Folli, L.; Bugini, R. Indagini sui materiali lapidei. Notiziatio Della Soprintendenza Archeologica Della Lombardia 1998, 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Mapelli, M.; Pitcher, L.P. First study on Roman mortar pavements from Cremona (Lombardy—Northern Italy). In Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium of Archaeometry, Siena, Italy, 12–16 May 2008; Turbanti-Memmi, E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Portulano, B.; Roffia, E. The analytical approach to the Roman mosaics: A case study in Northern Italy. In XI International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics; Bursa, 16–20 October 2009; Sahi, M., Ed.; Ege Yayinlari: Istanbul, Turkey, 2012; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L.; Ceresa, A. Features of two Roman mosaic floors from Milan (1st–4th centuries CE). In Atti del XII Colloquio AIEMA; Venezia, 11–15 September 2012; Travabene, G., Ed.; Scripta: Venezia, Italy, 2015; pp. 489–492. [Google Scholar]

- Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Caratteristiche di pavimenti romani e delle loro malte. In Atti del VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeometria; Pavia, 15-18/02/2010; Ricciardi, M.P., Basso, E., Eds.; Pàtron Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Portulano, B.; Bugini, R.; Folli, L. Caratteri stratigrafici di mosaici romani di Aquileja. In I Mosaici. Cultura, Tecnologia, Conservazione; Bressanone, 2–5 July 2002; Biscontin, G., Driussi, G., Eds.; Scienza e Beni Culturali, XVIII; Arcadia: Venezia, Italy, 2002; pp. 637–646. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, M.; Dilaria, S.; Addis, A.; Bonetto, J.; Artioli, G.; Salvadori, M. Evolution of the Vitruvian recipes over 500 years of floor making techniques: The case studies of Domus delle Bestie Ferite and Domus di Tito Macro (Aquileia, Italy). Archaeometry 2018, 60, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, C.; Dilaria, S.; Mazzoli, C.; Salvadori, M. Making Roman mosaics in Aquileia (I BC–IV AD): Technology, materials, style and workshop practices. Two case studies from Domus delle Bestie Ferite. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Classical Archaeology—AIAC, Cologne/Bonn, Germany, 22–26 May 2018; Thomas, R., Ed.; Propylaeum: Cologne, Germany, 2021; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, J.; Artioli, G.; Secco, M.; Addis, A. L’uso delle polveri pozzolaniche nei grandi cantieri della Gallia Cisalpina in età romana repubblicana: I casi di Aquileia e Ravenna. In Arqueología de la Construcción V. Man-Made Materials, Engineering and Infrastructure, Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on the Archaeology of Roman Construction, Oxford, UK, 11–12 April 2015; De Laine, J., Camporeale, S., Pizzo, A., Eds.; Editorial CSIC Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S. Appendice: Analisi archeometriche dei calcestruzzi idraulici fondazionali. In Aquileia. Fondi Cossar. 2. La Domus di Tito Macro e le Mura. 2.1 L’età Repubblicana e Imperiale; Bonetto, J., Furlan, G., Previato, C., Eds.; Scavi di Aquileia II; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2023; pp. 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Secco, M.; Bonetto, J.; Artioli, G. Technical analysis on materials and characteristics of mortar-based compounds in Roman and Late Antique Aquileia (Udine, Italy): A preliminary report. In Proceedings of the 5th Historic Mortars Conference HMC2019, Pamplona, Spain, 19–21 June 2019; Álvarez, J.I., Fernández, J.M., Navarro, Í., Durán, A., Sirera, R., Eds.; Rilem: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 665–679. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).