Blockchain-Based Batch Authentication and Symmetric Group Key Agreement in MEC Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Contributions

- (1)

- A unified “Authentication–Negotiation” security architecture is proposed. To overcome the limitations of traditional schemes that isolate authentication from negotiation, a tightly coupled protocol framework is designed. By reusing the parameters from the chameleon-hash authentication phase for the subsequent group key agreement, the protocol achieves joint optimization of communication and computation, reducing overall system overhead.

- (2)

- A lightweight chameleon-hash primitive tailored for MEC is constructed. A specific chameleon hash function based on elliptic curves is developed. By leveraging its trapdoor collision property for efficient signature aggregation, the computational complexity of batch verification is reduced from linear to near-constant time, thereby addressing efficiency bottlenecks in high-concurrency scenarios.

- (3)

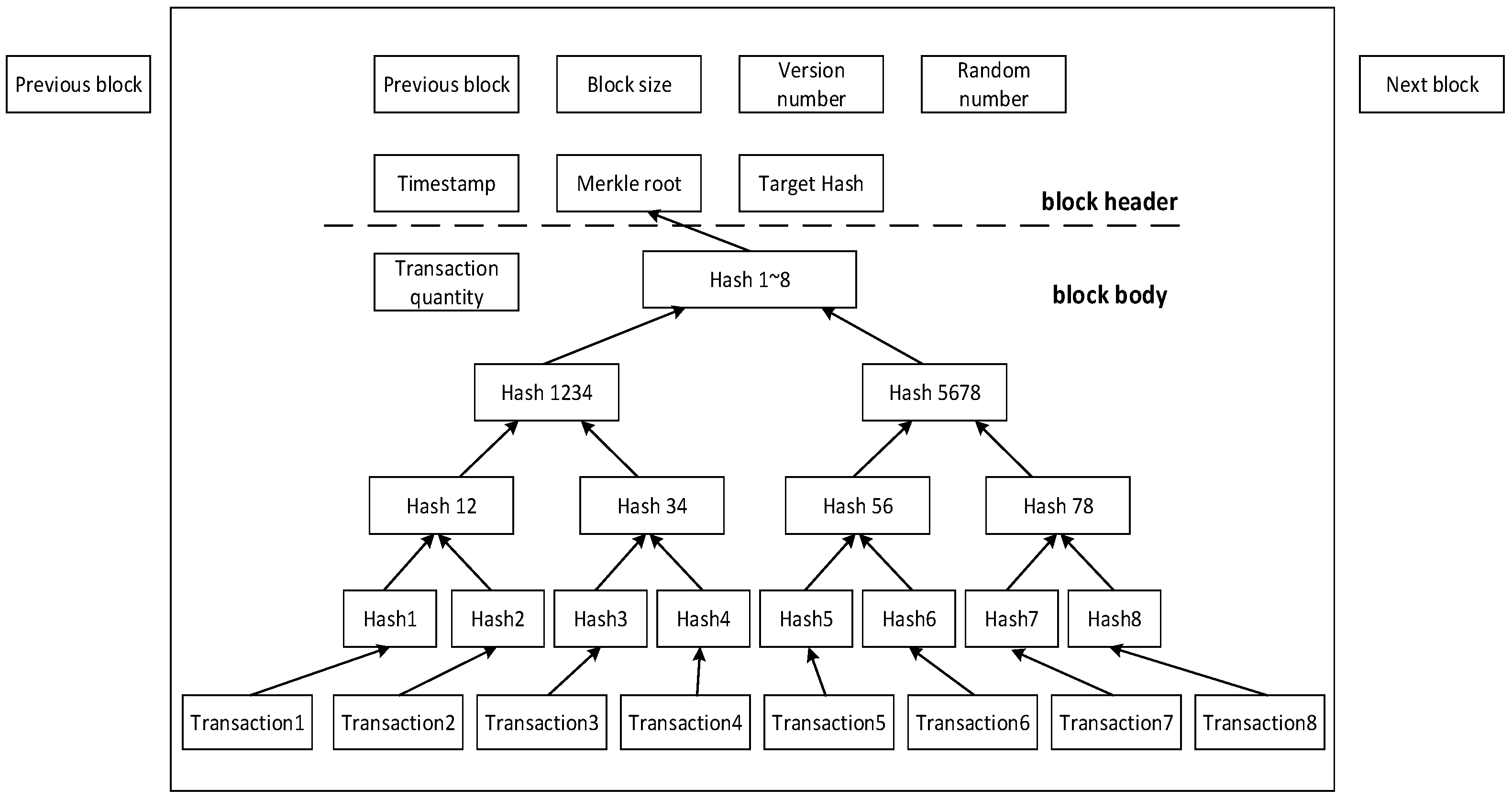

- A Merkle Tree-based mechanism against internal attacks is designed. Merkle Trees are applied to session key verification in an innovative way. This mechanism enables terminals to independently validate the correctness of keys, thus providing a theoretical guarantee against internal tampering attacks by semi-trusted ES and filling a security gap in existing schemes.

1.4. Organization

2. System Model and Protocol

2.1. Blockchain Technology Overview

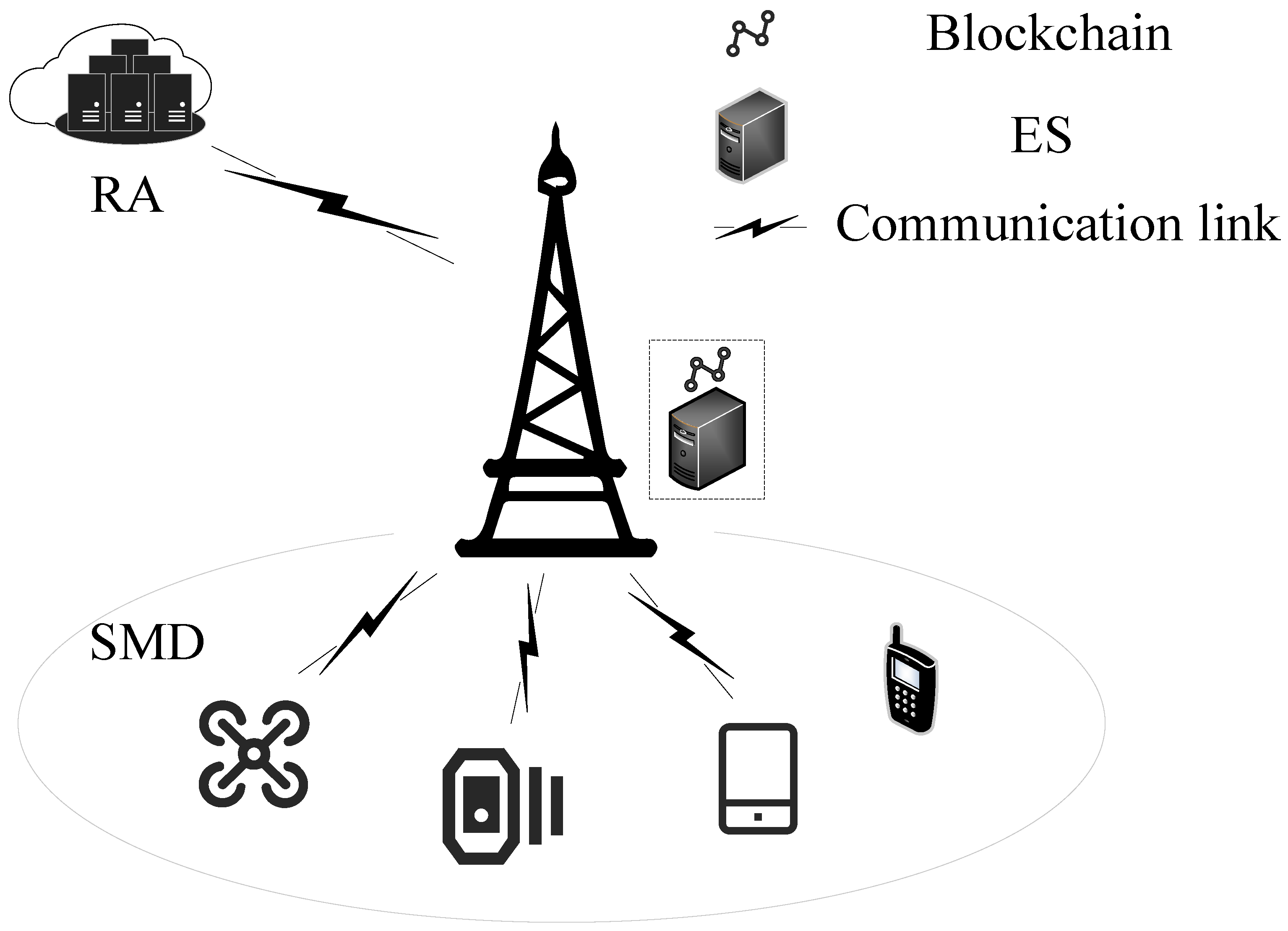

2.2. System Model

- (1)

- RA: The RA is a fully trusted entity deployed on the cloud server and trusted by all participants. Its primary responsibilities include registering and updating both SMDs and ESs, as well as maintaining the integrity of the data stored on the blockchain.

- (2)

- ES: The ES is a semi-trusted entity equipped with moderate storage and computational capabilities. The permissioned blockchain is located at the edge layer. The ES follows an honest-but-curious model, meaning that it correctly executes the key agreement protocol but may attempt to infer or leak user privacy information.

- (3)

- SMD: The SMD represents the user entities in the MEC system, such as UAVs, smartphones, and smartwatches. An SMD may connect to multiple ESs, but it typically selects the nearest one for authentication.

- (4)

- BC: The BC operates as a permissioned blockchain, which stores device identity information and key materials. Smart contracts are employed to manage key materials—recording, updating, and revoking them as necessary—thereby serving as a trusted and secure container for key management operations.

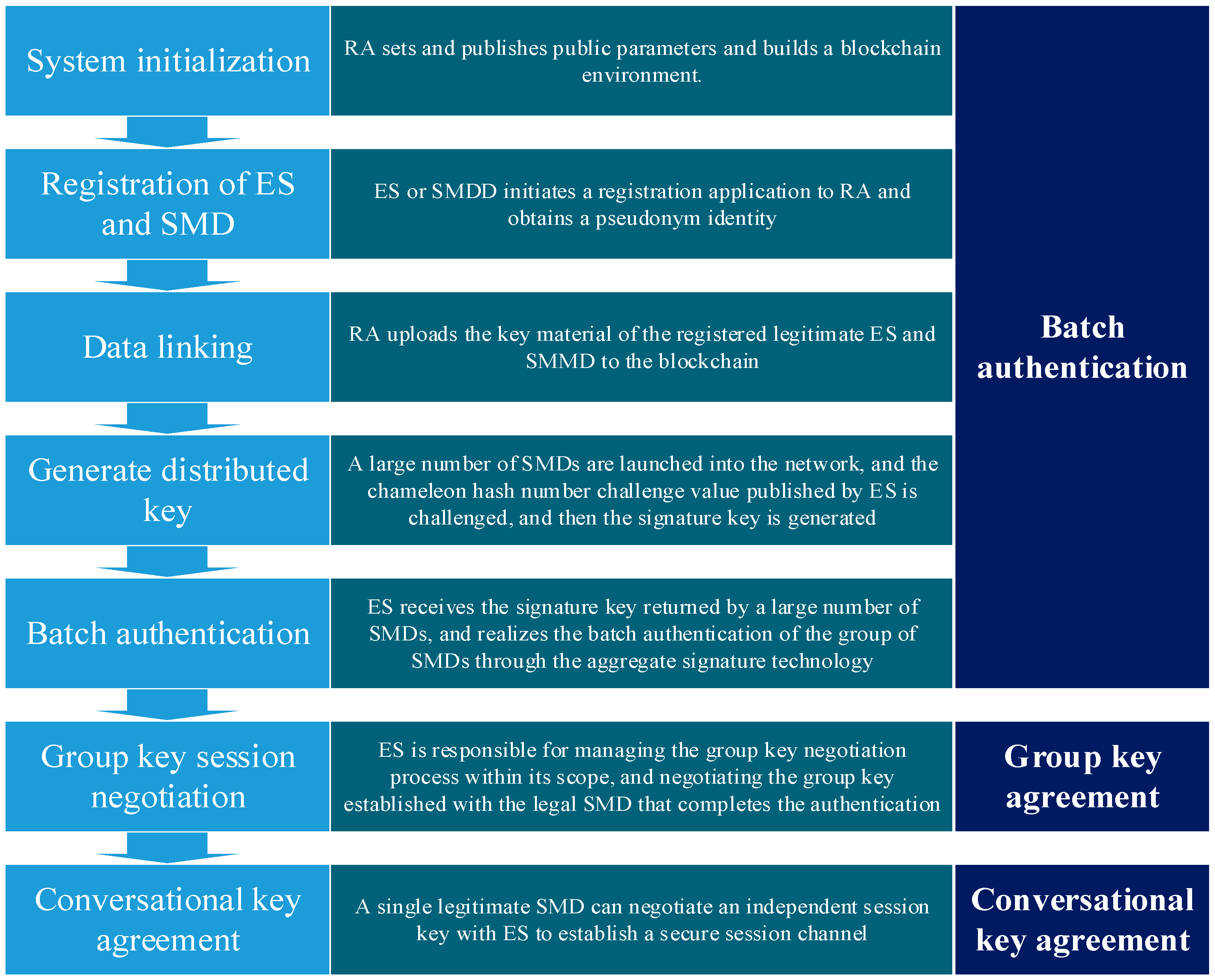

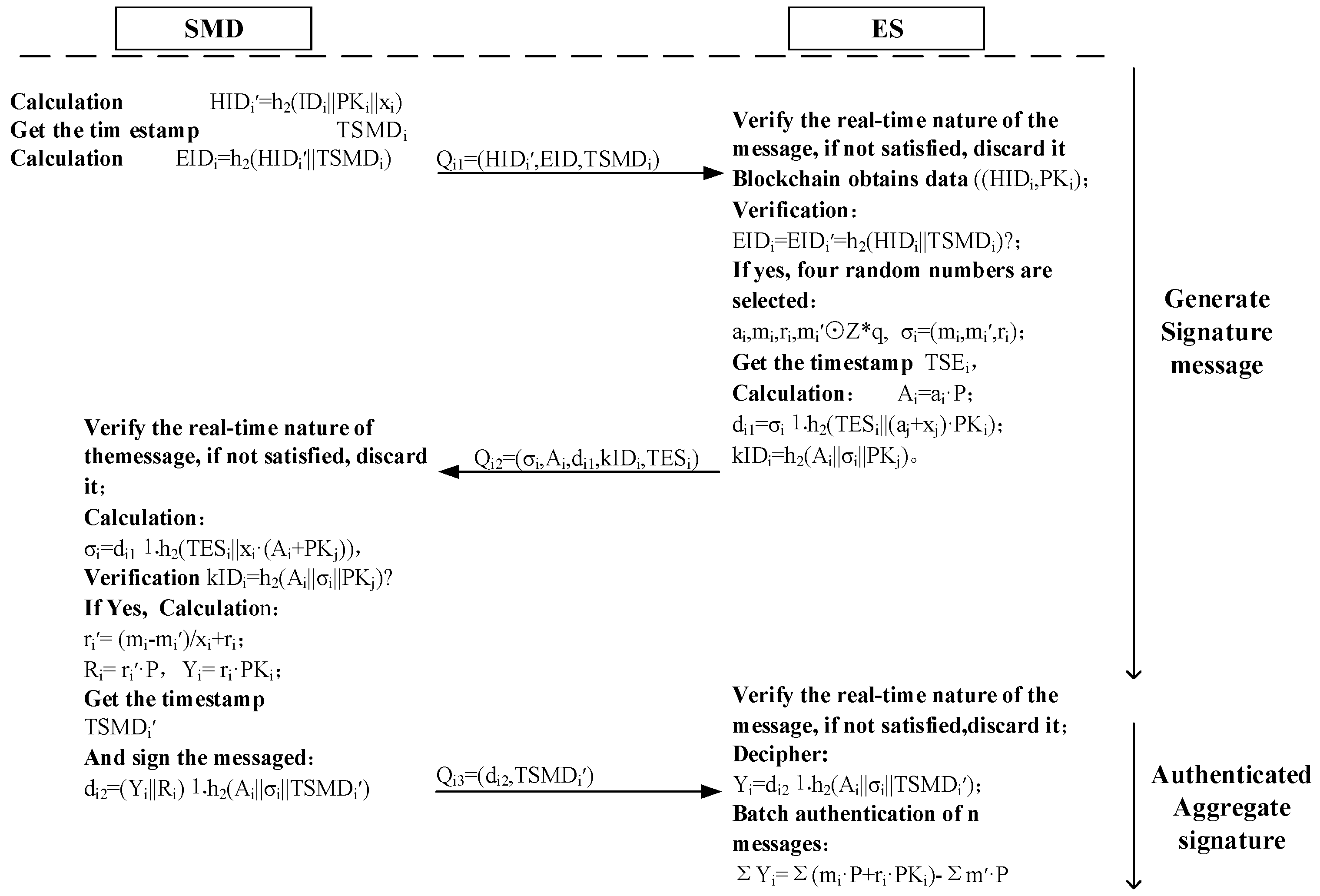

2.3. Batch Authentication Protocol in MEC

2.3.1. System Initialization Phase

2.3.2. Registration Phase of ES and SMD

- (1)

- -

- Upon receiving , the RA selects a random number and computes , , and ;

- -

- The RA then computes , and . Then the RA securely stores ;

- -

- The RA calculates , and sends the message to the SMD.

- (2)

- -

- Upon receiving M1, the SMD computes , , then verifies whether . If the verification succeeds, the SMD securely stores .

2.3.3. Data On-Chain Phase

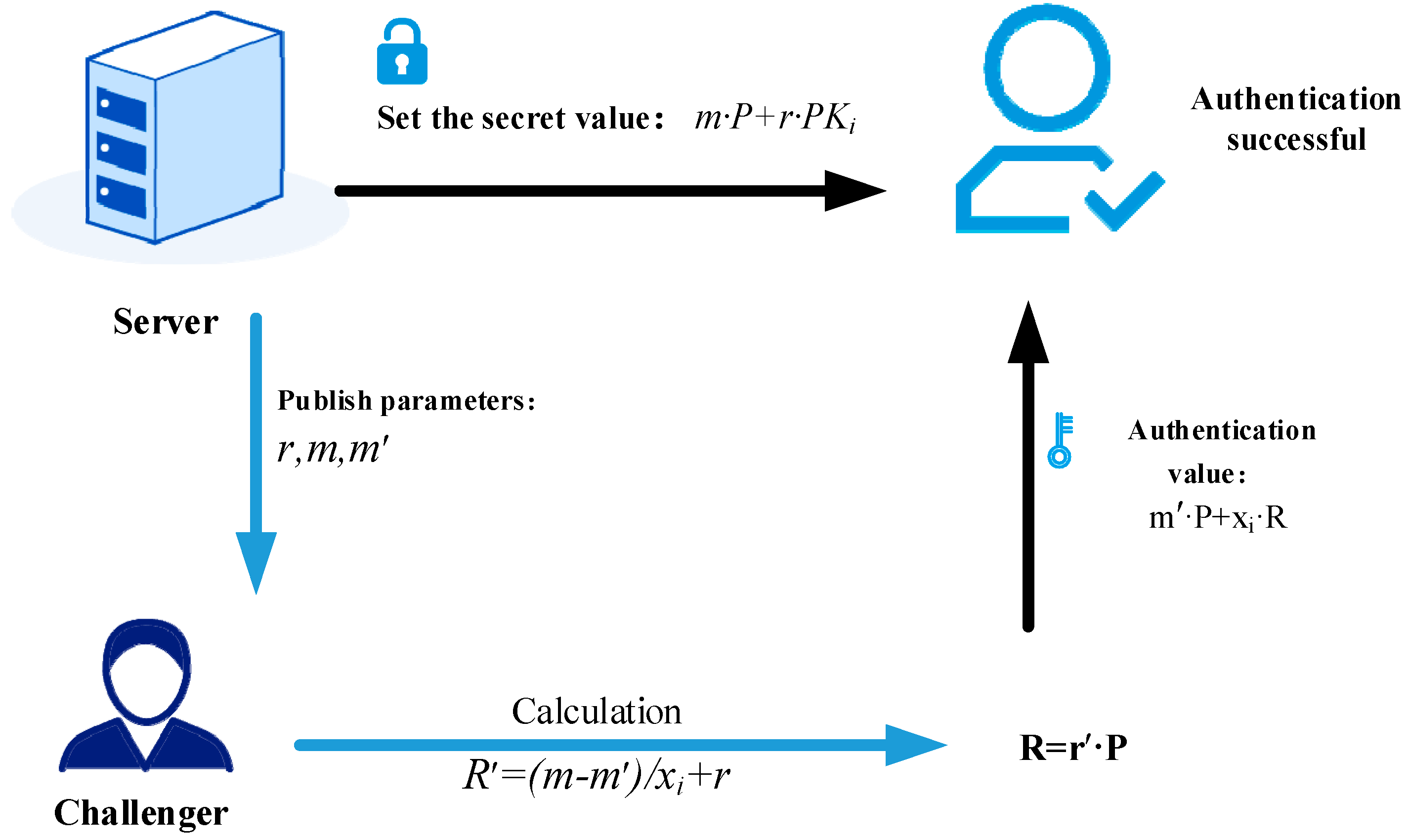

2.3.4. Distributed Key Generation Phase

- (1)

- -

- The SMD computes , then obtains the current timestamp and calculates ;

- -

- Next, the SMD sends to the ES.

- (2)

- -

- The ES first verifies the timeliness of the message by checking whether the relation holds, where is the preset time threshold and T is the current timestamp of the ES. All subsequent time verifications are performed in the same manner. The ES then uses to query the blockchain and retrieve the corresponding data tuple (, ), after which it computes and verifies . If the verification fails, the ES discards the message and rejects the request. Otherwise, the ES selects four random numbers , records them as , and then computes ;

- -

- To safeguard data communication across the public channel, the ES must perform encryption on the transmitted data. The ES obtains the current timestamp , then computes and the verification value ;

- -

- The ES sends message to the SMD.

- (3)

- -

- The SMD first checks the timeliness of the received message. If the time condition is not satisfied, the data is discarded. Otherwise, the SMD decrypts and computes the data ;

- -

- The SMD computes and verifies whether holds. If the verification succeeds, the SMD proceeds to compute and . Then, the SMD calculates ;

- -

- Similarly, the SMD encrypts the data before transmission. The SMD obtains the current timestamp and computes ;

- -

- The SMD sends the data to the ES.

2.3.5. Batch Authentication Phase

- (1)

- The ES uses to verify the timeliness of the message. If the condition is not satisfied, the message is discarded. Otherwise, the ES decrypts the message ;

- (2)

- The ES performs batch authentication on the n signatures. It verifies whether the equation holds. If the equation is satisfied, the ES accepts the n signatures; otherwise, it rejects the n;

- (3)

- At this point, the ES completes the batch authentication of the SMDs.

- (1)

- First, according to the computation of the challenge value , it can be derived:

- (2)

- Then, the following equation can be derived:

- (3)

- So:

2.3.6. Group Key Agreement Phase

- (1)

- Negotiation Process for a New Terminal Joining the Session GroupIn the scenario where v new SMDs join the session group for group key agreement:

- (1)

- -

- Assume there are k SMDs currently in the group (if no existing SMDs are in the group, then k = 0), and n SMDs want to join the group. The ES selects a random number for each , computes , and the group key ;

- -

- Subsequently, the ES obtains the timestamp , encrypts , and computes , where i = 1, 2, …, k + n;

- -

- The ES computes the signature on the message and broadcasts message to nearby SMDs.

- (2)

- -

- verifies the timeliness of the message, if it is not satisfied, the message is discarded. Otherwise, the SMD decrypts and computes ;

- -

- The SMD verifies the signature, computes , and if equation holds, accepts as the group key.

- (2)

- The negotiation process for existing terminals leaving the session groupAssume that from a session group containing k SMDs, u members are preparing to leave. The process of updating the group key is similar to the key agreement process when new members join the session group; therefore, the description here will be simplified accordingly:

- (1)

- -

- Each remaining selects a random number , computes , and the group key ;

- -

- The ES obtains timestamp , computes , and signs ;

- -

- The ES broadcasts message to nearby SMDs.

- (2)

- -

- Similarly, the SMD verifies the message timeliness. If valid, it decrypts the newly received group key and verifies the correctness of the group key using the signature. If the verification succeeds, it sets as the new group key.

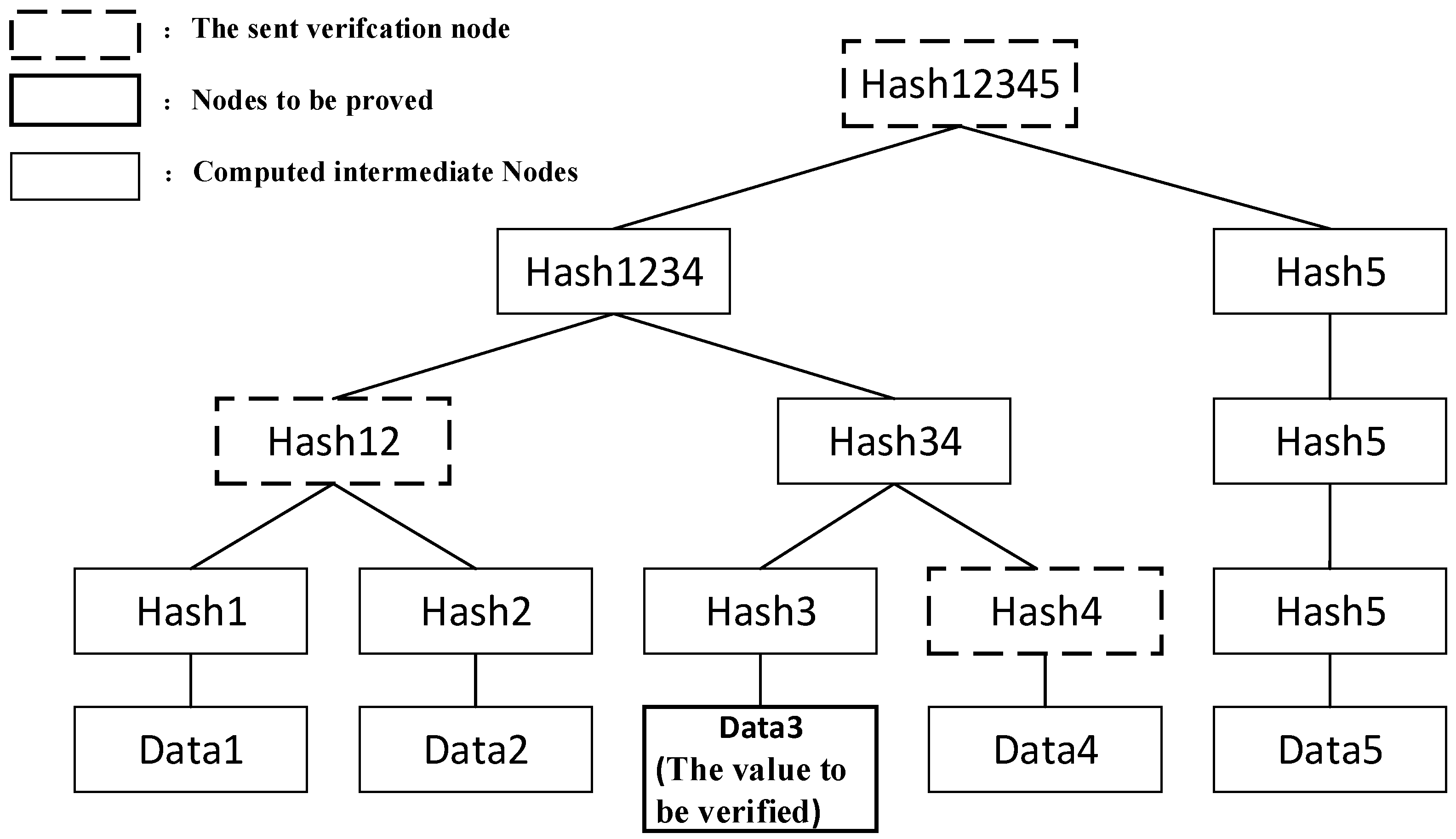

2.3.7. Session Key Agreement Phase

- (1)

- The ES computes using the random numbers and selected during the key setup phase, sets as the leaf nodes, and constructs the Merkle tree upwards to generate a Merkle root hash.

- (2)

- The ES broadcasts the root hash value and securely sends the hash values of the sibling nodes along the Merkle path to .

- (3)

- computes using (, , ) received during the setup phase, and uses this to verify the correctness of the Merkle root and the hash values of the sibling nodes at each level.

- (4)

- If the verification is correct, stores the received Merkle root and the hash values of the sibling nodes at each level.

3. Security Analysis

3.1. Informal Security Analysis

- (1)

- Mutual Authentication. Mutual authentication indicates that the SMD and the ES achieve mutual, bidirectional authentication. During the authentication process between the SMD and the ES, the SMD can authenticate the identity of the ES via the RA. Conversely, the ES authenticates the members within the group and those wishing to join by performing aggregate signature verification using the chameleon Hash algorithm, thereby authenticating the SMDs.

- (2)

- Conditional Anonymous Traceability. Conditional anonymity indicates that throughout the authentication and key agreement process, the SMD sends data anonymously, and only the RA has the authority to trace its real identity. The SMD uses the pseudonym to send messages, which are stored on the blockchain and protected by the user’s private key and a secure hash function. An adversary can only analyze the user’s real identity by solving the one-way hash function problem and breaking the user’s private key; however, the success probability of this assumption is negligible. When tracing the message source is required, the RA can decrypt and compute the SMD’s real identity . Therefore, the protocol provides conditional anonymous traceability.

- (3)

- Forward and Backward Secrecy. In the protocol proposed in this paper, the group key agreement phase only allows authenticated SMDs to participate and successfully generate the group’s public session key. Unauthenticated SMDs or adversaries cannot obtain this session key. Furthermore, the group key () generation method involves each SMD and the challenge value provided by the ES jointly participating in the computation. Whenever a new vehicle joins or an old SMD leaves, the ES issues a new challenge value and updates the group key. Any newly joined SMD, departed SMD, or adversary cannot deduce the previous key () or the subsequent key () from the current session key (). Therefore, the protocol ensures both forward and backward secrecy.

- (4)

- Resistance to Sybil Attacks. A Sybil attack refers to an adversary attempting to disrupt the normal operation of the network by creating bogus SMDs to send forged messages. In the proposed protocol, the identity of each SMD is authenticated by the ES upon completion of registration; any non-legitimized SMD will not be recognized. Furthermore, an adversary might cause a batch verification containing forged signatures to pass incorrectly by selecting specific messages and forging opposing signatures. However, in the proposed protocol, the ES provides a unique challenge value to each legitimate SMD, which prevents adversaries from forging signatures and breaks the linear relationship in the aggregate signature.

- (5)

- Resistance to Replay Attacks. A replay attack is an act where an attacker intercepts and re-sends data packets to deceive the system. The proposed protocol effectively resists replay attacks by utilizing a timestamp and hash-signature mechanism. It ensures communication freshness by checking the message timestamp for a reasonable time difference , and ensures the timestamp has not been tampered with via its inclusion in the hash. This prevents both conventional replay attacks and replay attacks where the attacker modifies the timestamp.

- (6)

- Resistance to Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) Attacks. A MitM attack is a network security threat where an attacker intercepts and potentially modifies the communication between two parties. In this protocol, the Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman key exchange between the SMD and the ES, combined with the use of cryptographic hash functions, ensures the authenticity of both parties. To forge a message, an adversary would need the private key of either the SMD or the ES, which remains confidential and is not exposed to the attacker. Therefore, the protocol can effectively resist MitM attacks.

- (7)

- Resistance to Denial-of-Service (DoS) Attacks and Scalability. The proposed protocol employs a multi-layered defense strategy to mitigate DoS threats and ensure high scalability. Firstly, the ES performs lightweight pre-filtering by verifying the freshness of timestamps TSMD and the validity of identities IDi before executing computationally intensive cryptographic operations, effectively discarding replayed or illegitimate requests at negligible cost. Secondly, the core aggregate signature mechanism establishes a significant computational asymmetry: the cost for an adversary to generate massive valid signatures is significantly higher than the ES’s cost to verify them in a batch, thereby inherently suppressing computational DoS attacks. Finally, for practical deployment, we recommend incorporating rate-limiting mechanisms (e.g., Token Bucket algorithm) based on IP or ID at the ES side to further block malicious high-frequency triggers from specific sources, ensuring system availability.

- (8)

- Resistance to Internal Server Attacks. Although our system model assumes an “honest-but-curious” semi-trusted ES, we also address the scenario where an ES becomes malicious or colludes with other entities. Firstly, the protocol adheres to the principle of data minimization; the ES acts solely as an authentication executor and does not store any long-term private keys or sensitive identity information of the SMDs. Therefore, even if an ES is compromised or colludes, it cannot leak critical credentials to compromise an SMD’s security. Secondly, relying on the permissioned blockchain architecture, only authorized ESs are registered. During authentication, the SMD strictly verifies the ES’s legitimacy using its public key . If the ES fails verification or is determined to be unreliable, the SMD will immediately abort the connection and refuse access through that ES, effectively isolating the threat from malicious servers.

- (9)

- Resistance to Blockchain-Specific Attacks and Side-Channel Threats. Addressing blockchain-specific vectors, our scheme is deployed on a permissioned consortium blockchain utilizing the Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) consensus algorithm. PBFT provides deterministic finality, inherently preventing forking issues common in public chains, and effectively resists consensus manipulation as long as malicious nodes do not exceed one-third of the total network. Regarding smart contract vulnerabilities, the contract logic in our protocol is restricted to simple key-value lookups and hash verifications without complex asset transfers, and has undergone rigorous logic testing to minimize the attack surface. Furthermore, regarding side-channel threats, our protocol design avoids conditional branching based on secret values. In the implementation, we adopt constant-time cryptographic primitives (leveraging standard configurations of the Multiprecision Integer and Rational Arithmetic C Library (MIRACL)) to eliminate timing leakages.

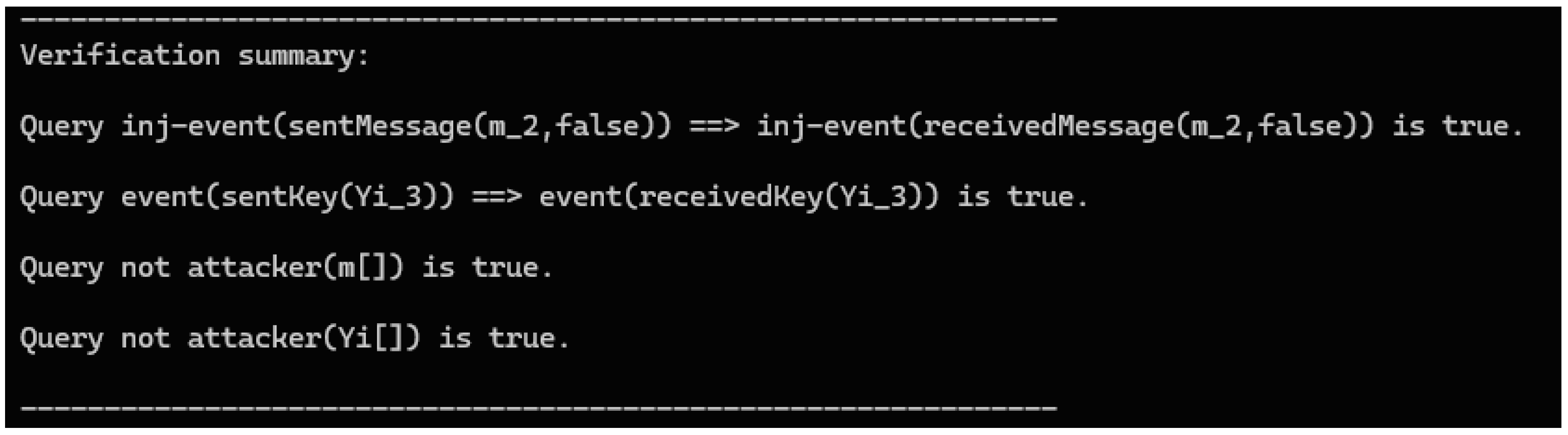

3.2. Formal Analysis Using the ProVerif Tool

3.3. Formal Analysis of GKA Phase Using BAN Logic

4. Results and Discussion

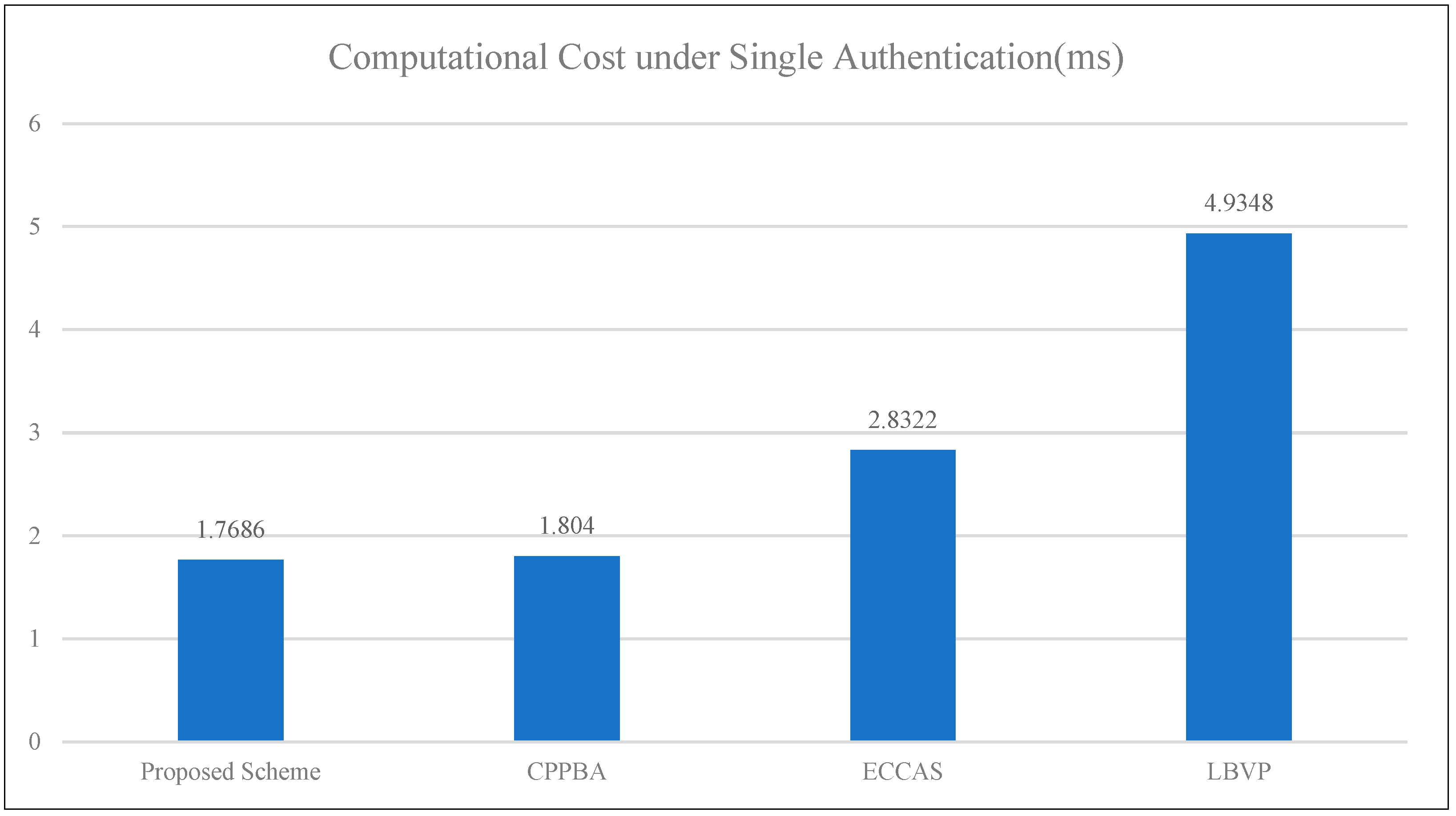

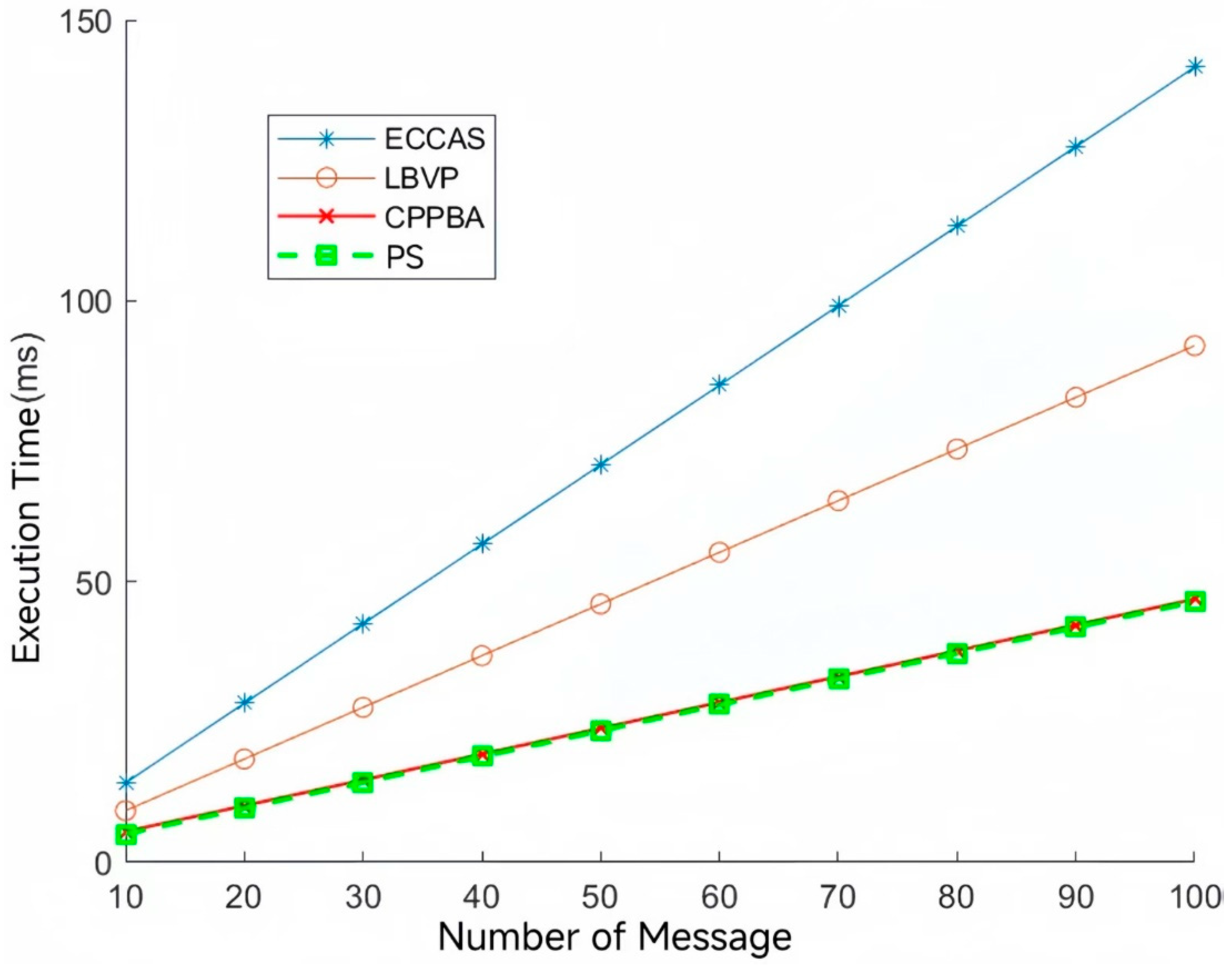

4.1. Comparative Analysis of the Computational Cost of Batch Authentication

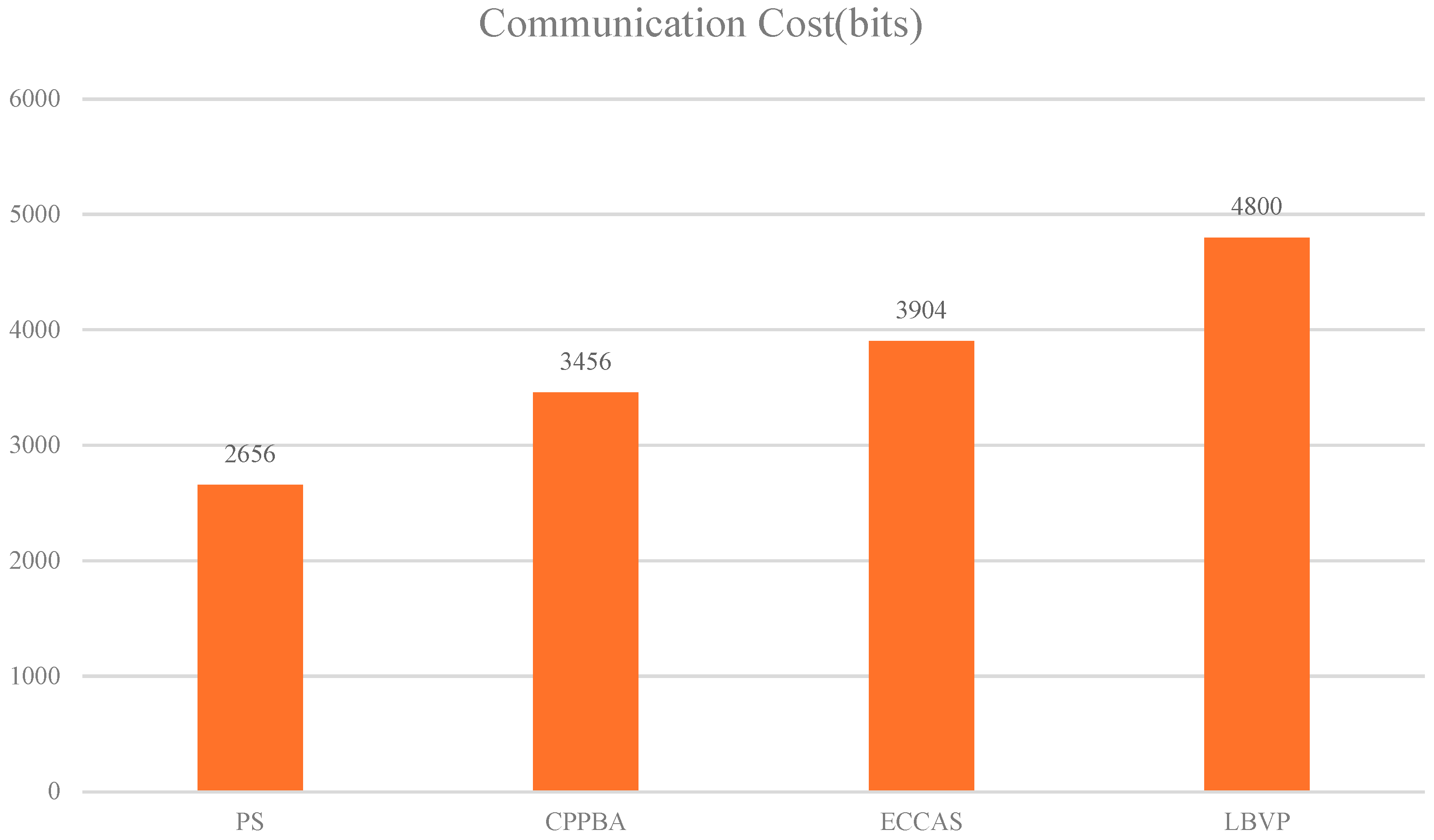

4.2. Batch Authentication Communication Cost Comparative Analysis

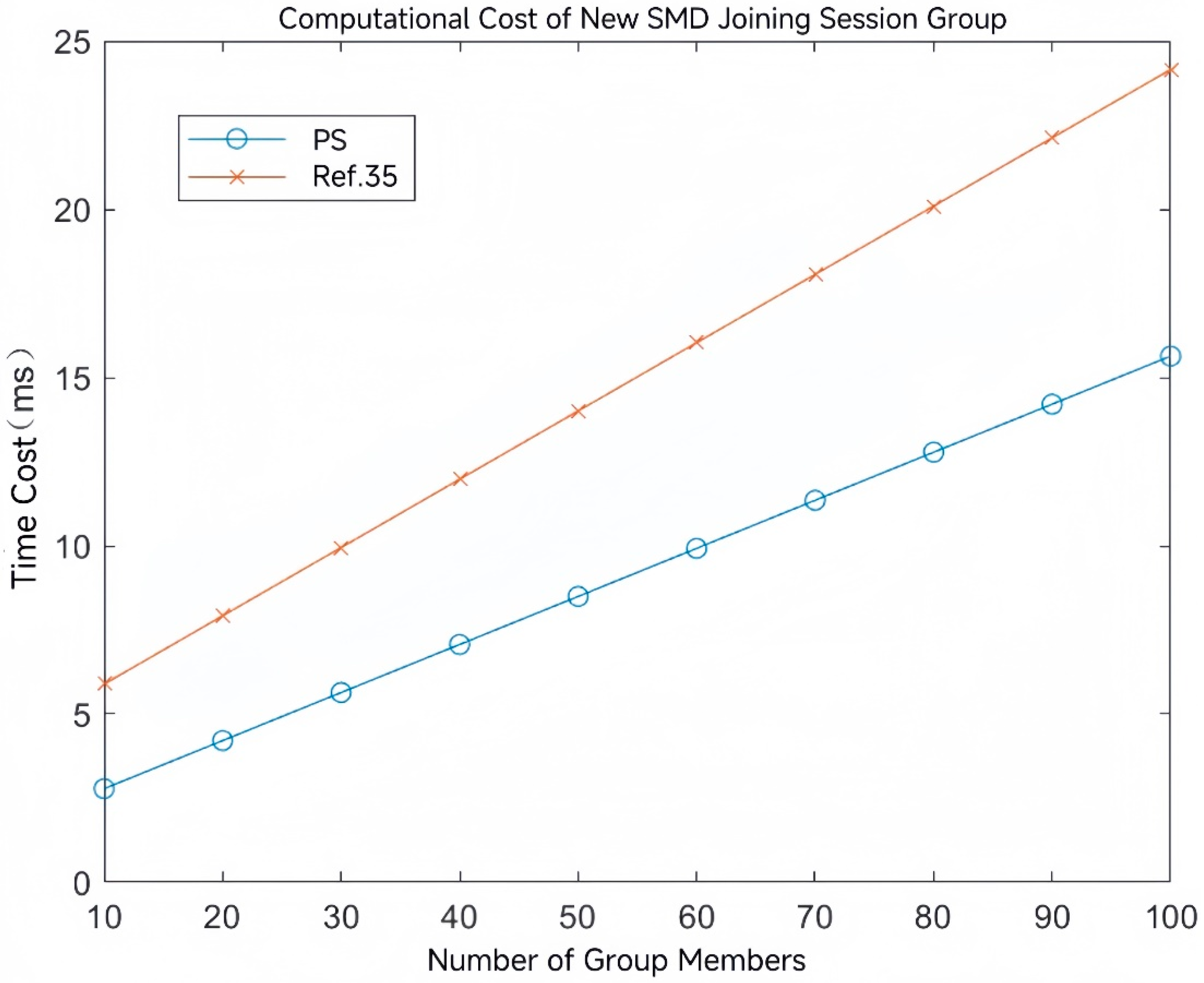

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Group Key Agreement

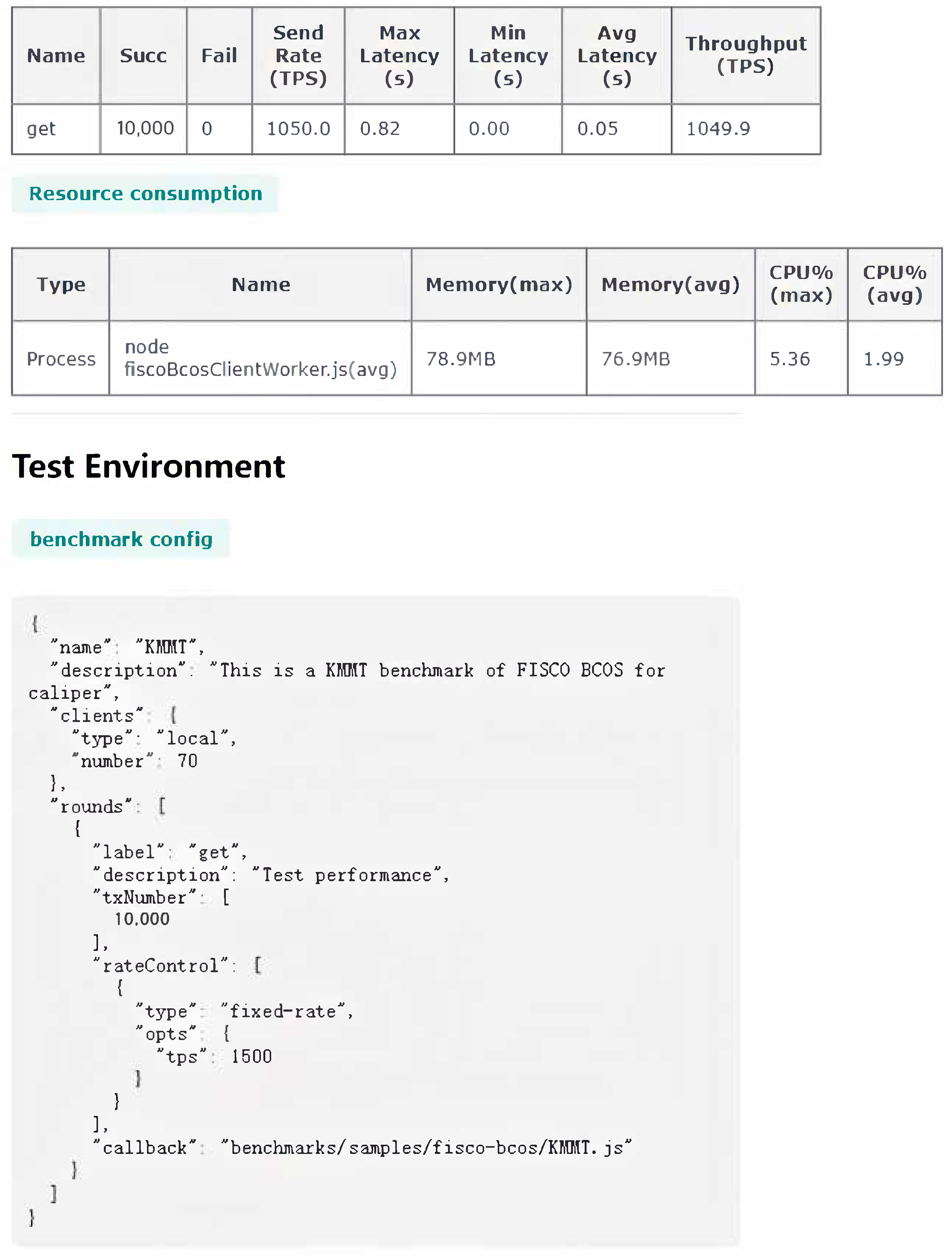

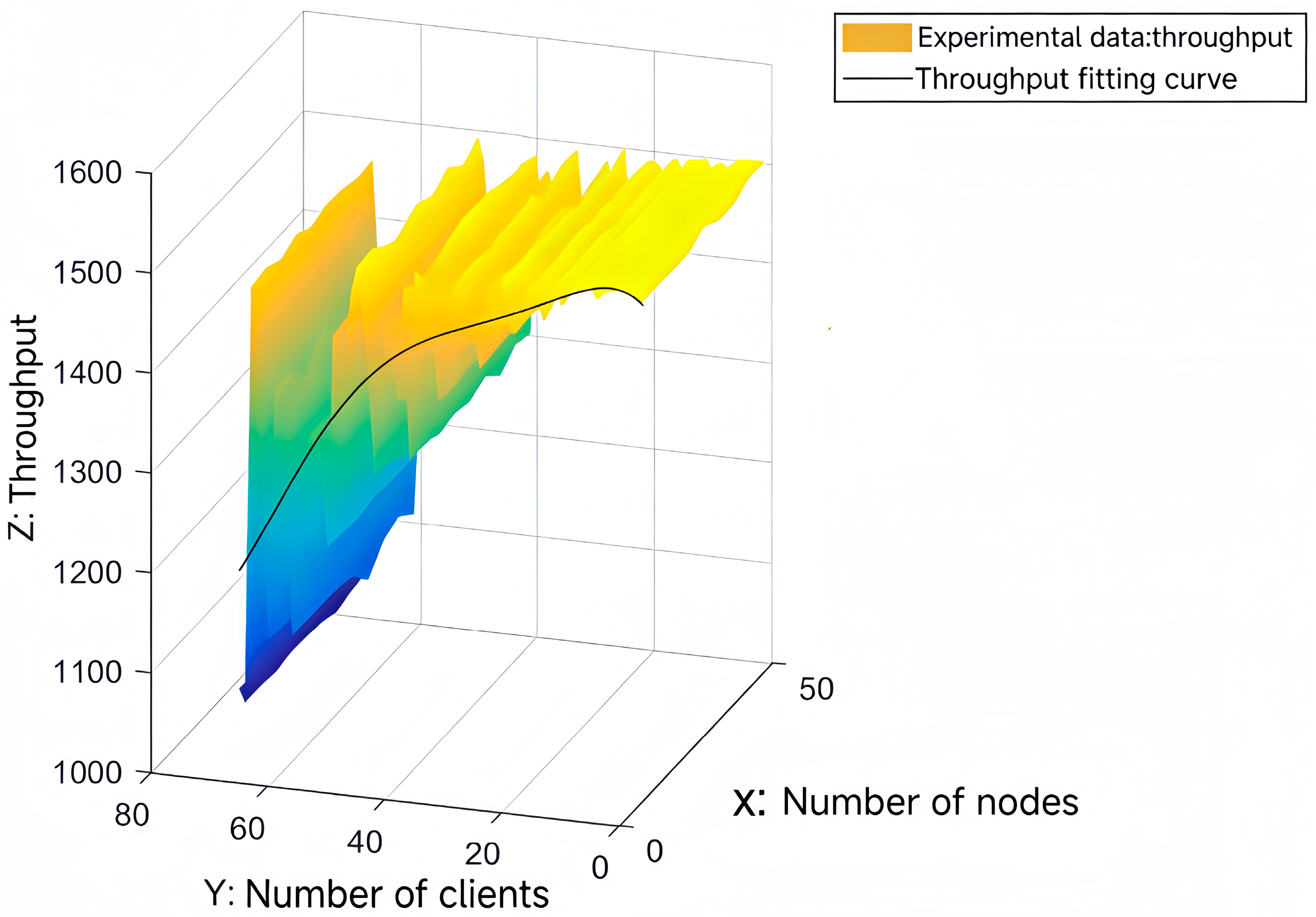

4.4. Blockchain Performance Evaluation

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scheme (Ref.) | Core Technique | Batch Auth | GKA | Decentralized Trust | Anti-Internal Attack | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refs. [21,22] | CRT/Chaotic Map | √ | √ | × | × | Relies on centralized trust models; Vulnerable to internal attacks from semi-trusted servers. |

| Ref. [23] | Distributed Collab. | √ | × | × | × | Coordination between nodes adds communication overhead; Lacks blockchain auditing. |

| Ref. [24] | BLS Threshold Sig | × | × | √ | × | Focuses on optimizing threshold signature security; Not specifically optimized for massive batch access in MEC. |

| Ref. [25] | Pairing-free Signcryption | × | √ | × | × | Efficient but lacks a blockchain trust anchor; Does not support batch verification. |

| Ref. [28] | Chameleon Hash + ABE | × | × | √ | √ | Focuses on redactable storage and fine-grained access control; Not designed for concurrent authentication. |

| Ref. [32] | Blockchain + CL-AKA | √ | √ | √ | × | Achieves lightweight privacy protection for V2V, but lacks aggregation optimization for ultra-scale batch verification. |

| Ref. [37] | Blockchain + ECC | √ | × | √ | × | Achieves decentralized authentication but lacks a subsequent group key agreement mechanism. |

| Proposed | Chameleon Hash + Merkle Tree | √ | √ | √ | √ | (Advantage) Unifies authentication and negotiation; Effectively resists internal attacks via Merkle Tree. |

Appendix B

References

- Zhang, X.; Debroy, S. Resource management in mobile edge computing: A comprehensive survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ryu, J.; Won, D. Secure and anonymous authentication scheme for mobile edge computing environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 5798–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Jia, Y.; Liu, C.; Cheng, X.; Yu, J.; Lv, W. Edge computing security: State of the art and challenges. Proc. IEEE 2019, 107, 1608–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.G.; Mosa, D.T.; Abualigah, L.; Abohany, A.A. Emerging trends in blockchain technology and applications: A review and outlook. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 6719–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichen, M.; Ammi, M.; Mihoub, A.; Almutiq, M. Blockchain for modern applications: A survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, K. zk-AuthFeed: Protecting data feed to smart contracts with authenticated zero knowledge proof. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2022, 20, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Srivastava, G.; Karimipour, H. Secure intelligent fuzzy blockchain framework: Effective threat detection in iot networks. Comput. Ind. 2023, 144, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadi, O.; Moustafa, N.; Turnbull, B.; Choo, K.-K.R. A deep blockchain framework-enabled collaborative intrusion detection for protecting IoT and cloud networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 9463–9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Tripathi, R.; Gupta, G.P.; Garg, S.; Hassan, M.M. A distributed intrusion detection system to detect DDoS attacks in blockchain-enabled IoT network. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2022, 164, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, R.; Al-Turjman, F.; Bhatla, S.; Mishra, D. Mobile edge fog, Blockchain Networking and Computing–A survey. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Technology and Networking (CICTN), Ghaziabad, India, 20–21 April 2023; pp. 808–811. [Google Scholar]

- Tanveer, M.; Alharbi, A.G.; Akhtar, M.J. A secure and resource-efficient authenticated key agreement framework for mobile edge computing. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, X. A secure anonymous identity-based scheme in new authentication architecture for mobile edge computing. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 15, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, C.; Chaurasiya, V.K. Efficient anonymous batch authentication scheme with conditional privacy in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) applications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 9670–9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, C.; Zhong, H. Efficient batch authentication scheme based on edge computing in IIoT. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 20, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.; Dakhilalian, M.; Susilo, W. Efficient chameleon hash functions in the enhanced collision resistant model. Inf. Sci. 2020, 510, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanalakshmi, P.; Anitha, R.; Anbazhagan, N.; Cho, W.; Joshi, G.P.; Yang, E. A hash-based quantum-resistant chameleon signature scheme. Sensors 2021, 21, 8417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shen, Q.; Xie, Z.; Dong, J.; Fang, Y.; Wu, Z. Efficient identity-based chameleon hash for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022–2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 3039–3043. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, K.; Sui, Z.; Zhao, J. Blockchain-based synchronized data transmission with dynamic device management for digital twin in IIoT. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, H.; Cui, J.; Li, J.; He, D. Device-side lightweight mutual authentication and key agreement scheme based on chameleon hashing for industrial internet of things. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 7895–7907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modiri, M.M.; Mohajeri, J.; Salmasizadeh, M. A novel group-based secure lightweight authentication and key agreement protocol for machine-type communication. Sci. Iran. 2022, 29, 3273–3287. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.B.; Chen, Z.; Huang, H.W.; He, X.F. Intra-group mutual authentication key agreement protocol based on Chinese remainder theorem in VANET system. J. Commun. 2022, 43, 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J.; Wang, Z.; Miao, X.; Xing, L. A secure and efficient lightweight vehicle group authentication protocol in 5G networks. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 4079092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Fan, W.; Liu, Y. Batch-assisted verification scheme for reducing message verification delay of the vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 8144–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ren, L. Adaptively secure BLS threshold signatures from DDH and co-CDH. In Annual International Cryptology Conference; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 251–284. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.R.; Moulik, S.; Thokchom, S. A novel pairing free certificateless aggregate signcryption scheme for IoMT. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 123, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, L.; Feng, Z.S. Lightweight dynamic key management scheme for UAV group. Appl. Res. Comput. 2023, 40, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Li, X.; Jiao, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, A.; Su, C.; Zheng, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, X. BAGKD: A batch authentication and group key distribution protocol for VANETs. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, D. Redactable consortium blockchain with access control: Leveraging chameleon hash and multi-authority attribute-based encryption. High-Confid. Comput. 2024, 4, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T. Research on Safe and Efficient Message Authentication Method in Vehicle Ad Hoc Network Environment. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Polytechnic University, Shaanxi, China, April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.W.; Xue, Q.S.; Sun, C.X.; Ma, H.F.; Ju, X.Z.; Cui, M.X. Batch zero-knowledge identity authentication scheme based on attribute access strategy. Appl. Res. Comput. 2023, 40, 2487–2492. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Shi, Q.; Xie, Q.; Wang, L. P2BA: A privacy-preserving protocol with batch authentication against semi-trusted RSUs in vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 3888–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Jhuang, W.L. Blockchain-based lightweight certificateless authenticated key agreement protocol for V2V communications in IoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 27744–27759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhong, H.; Cui, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L. An extensible and effective anonymous batch authentication scheme for smart vehicular networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 3462–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrala, A.K.; Bagga, P.; Das, A.K.; Kumar, N.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Lorenz, P. On the design of conditional privacy preserving batch verification-based authentication scheme for internet of vehicles deployment. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 5535–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Wang, H.Q. Dynamic Key Management of Industrial Internet Based on Blockchain. J. Comput. Res. Dev. 2023, 60, 386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.G.; Dong, G.F. Blockchain-based vehicle-to-infrastructure fast handover authentication scheme in VANET. J. Comput. Appl. 2024, 44, 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; He, D.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L. An efficient blockchain-based batch verification scheme for vehicular ad hoc networks. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; He, D.; Kumar, N.; Raymond Choo, K.-K. A provably secure and efficient identity-based anonymous authentication scheme for mobile edge computing. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 14, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, Y.; Kumar, S.V.N.S. An elliptic curve cryptography based certificate-less signature aggregation scheme for efficient authentication in vehicular ad hoc networks. Wirel. Netw. 2024, 30, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.J.; Wang, R.M.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhou, F.; Luo, X.N. A Conditional Privacy-Preserving Batch Authentication Scheme Based on Certificateless Aggregate Signature for VANETs. J. Cryptologic Res. 2023, 10, 462–475. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, H.; Cui, J.; Bolodurina, I.; Liu, L. Lbvp: A lightweight batch verification protocol for fog-based vehicular networks using self-certified public key cryptography. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 5519–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Lan, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R.Y.; Zou, C.; Wang, M.Y. Ring-based efficient batch authentication and group key agreement protocol with anonymity in Internet of vehicles. J. Commun. 2023, 44, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Meaning |

|---|---|

| q | Large prime number |

| s | System private key |

| PK | System public key |

| IDi | Identity of the i-th SMD |

| IDj | Identity of the j-th ES |

| (xi, PKi) | Private/public key pair of the i-th SMD |

| (xj, PKj) | Private/public key pair of the j-th ES |

| HIDi | Signature data of the i-th SMD |

| mi, ri, mi′ | chameleon hash function challenge random value |

| TSMDi, TESi | Timestamp |

| GSK | Group session key |

| SK | Session key shared between SMD and ES |

| hi(i = 1, 2) | Hash function |

| ⊕ | XOR encryption operation |

| || | Concatenation operator |

| Key Principal Events |

|---|

| event receivedMessage (bitstring, bool). |

| event receivedKey (point). |

| event sentMessage (bitstring, bool). |

| event sentKey (point). |

| Description of Security Objectives |

|---|

| query m: bitstring, Time: timestamp; inj-event (sentMessage(m,false)) ==> inj- event (receivedMessage (m, false)). |

| query Yi: point; event (sentKey (Yi)) ==> event (receivedKey (Yi)). |

| query attacker (m). |

| query attacker (Yi). |

| Main Verification Process |

|---|

| process |

| new IDi: bitstring; |

| new xi: bignum; |

| new xj: bignum; |

| (!SMD(IDi, xi | !ES(xj))) |

| Definitions | Description | Operation Costs (ES/Server) | Operation Costs (SMD/Mobile) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curve | Elliptic Curve Type (E/Fp) | Type-1 Pairing (p = 512 bits) | - |

| TGm | Scalar multiplication on G | 0.4420 ms | 19.9190 ms |

| TGa | Scalar addition on G | 0.0180 ms | 0.1180 ms |

| Th | Hash function | 0.0001 ms | 0.0890 ms |

| |G| | Bit length of an element in G | 1024 bits | 1024 bits |

| |GT| | Bit length of an element in GT | 1024 bits | 1024 bits |

| logq | Private Key Length (Size of Zq) | 160 bits | 160 bits |

| |T| | Timestamp length | 32 bits | 32 bits |

| |ID| | Identity length | 256 bits | 256 bits |

| Definitions | Single Request | Batch Processing | Operation Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBVP | 11TGm + 4TGa + 8Th | 2nTGm + 2nTGa + nTh | 4|G| + 4logq + 2|T| |

| ECCAS | 6TGm + 10TGa + 2Th | 3nTGm + 5nTGa + nTh | 3|G| + 5logq + |T| |

| CPPBA | 4TGm + 2TGa | (n + 2)TGm + nTGa | 3|G| + 2logq + 2|T| |

| PS 1 | 4TGm + 6Th | (n + 1)TGm + nTGa | |G| + 10logq + 3|T| |

| Cryptographic Operation | Operation Description | Execution Time/ms |

|---|---|---|

| Th | Hash Operation | 0.008 |

| Tse | Symmetric Encryption | 0.0183 |

| Tsd | Symmetric Decryption | 0.0182 |

| Tecc | Elliptic Curve Scalar Multiplication | 0.0514 |

| Tcm | Chebyshev Map | 0.0336 |

| New Device Join | New Group Key Establishment | |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed Scheme | nTh | (2k + 2n)Tecc + (4k + 4n + 1)Th |

| Ref. [42] | 4nTcm + 6nTh | 4(k + n)Tcm + (4k + 4n + 1)Th + (k + n)Tse + (k + n)Tsd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Li, J. Blockchain-Based Batch Authentication and Symmetric Group Key Agreement in MEC Environments. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122160

Deng Y, Zhang J, Liu J, Li J. Blockchain-Based Batch Authentication and Symmetric Group Key Agreement in MEC Environments. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122160

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Yun, Jing Zhang, Jin Liu, and Jinyong Li. 2025. "Blockchain-Based Batch Authentication and Symmetric Group Key Agreement in MEC Environments" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122160

APA StyleDeng, Y., Zhang, J., Liu, J., & Li, J. (2025). Blockchain-Based Batch Authentication and Symmetric Group Key Agreement in MEC Environments. Symmetry, 17(12), 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122160