Performance Analysis of a MIMO System Under Realistic Conditions Using 3GPP Channel Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. System Model

2.1. Simulator

2.2. Channel Models

- 3GPP Spatial Channel Model (SCM)/SCM-Extended (SCME)

- 3GPP WINNER II Channel Model (SCM extension)

- 3GPP TR 38.901 (5G Channel Model)—2D Option [11].

- 3GPP TR 36.873—3D Channel Model for LTE

- 3GPP TR 38.901—3D Channel Model for 5G NR [11].

2.3. Paper Contribution

- Transmission antenna power.

- Carrier frequency.

- The K-factor, which essentially determines the ratio between Line-of-Sight (LOS) and Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) conditions.

- Transmit power and antenna polarization.

- MIMO antenna configuration ratio.

- Ratio of indoor to outdoor users.

- User mobility speed.

- Use of an indoor propagation model.

- User density.

- Cell size.

3. Simulation Results

- Average Cell Throughput measures how much useful data a cell delivers per unit time, averaged over all active users.

- Average UE Throughput on the other hand measures how much data a specific user receives per unit time, averaged over the simulation or measurement interval.

- Average User Spectral Efficiency (SE) is a KPI used in LTE/5G/NR systems to measure how efficiently the radio spectrum is used by each user.

- Average Cell Spectral Efficiency (CSE) measures how efficiently an entire cell uses its radio spectrum.

- Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio (SINR) is one of the most important metrics in wireless communications because it directly describes how clearly a receiver can detect the desired signal in the presence of interference and noise [33].

- : Channel vector for UE u, layer l, resource n.

- : receive filter (ZF, MMSE, etc.).

- : allocated TX power for layer l.

- : Noise variance.

- : The set of RBs/subcarriers assigned to UE u at time t.

- : Bandwidth per subcarrier.

- (): only successful transmissions count.

- : Average UE spectral efficiency (bits/s/Hz).

- : Total system or allocated bandwidth.

- is the instantaneous user throughput (bits/s) produced by the LPM at time t.

- is the system bandwidth (Hz).

- is therefore the average UE spectral efficiency (bits/s/Hz).

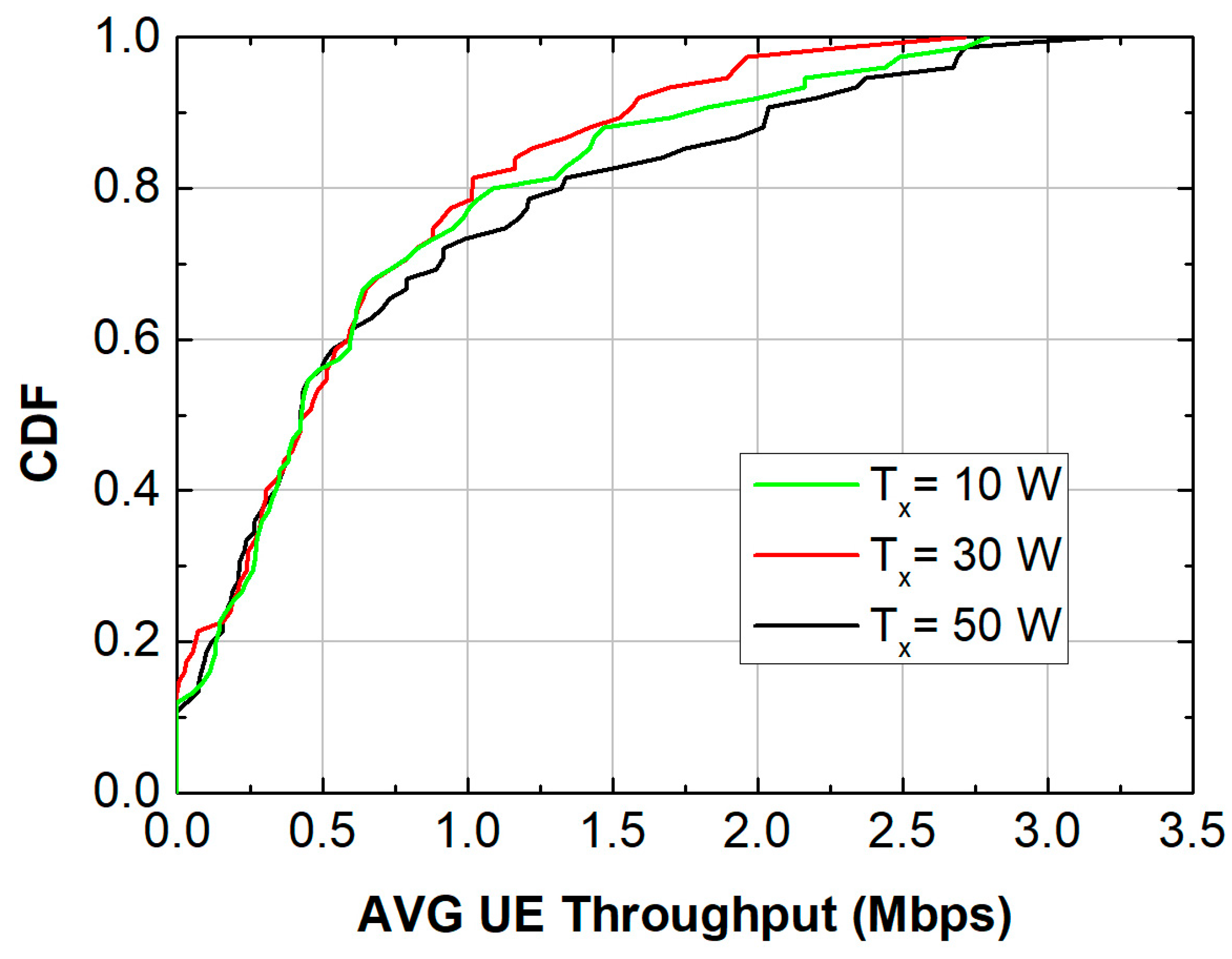

- Simulation 1: Increase Tx Power

- Simulation 2: Increasing Frequency

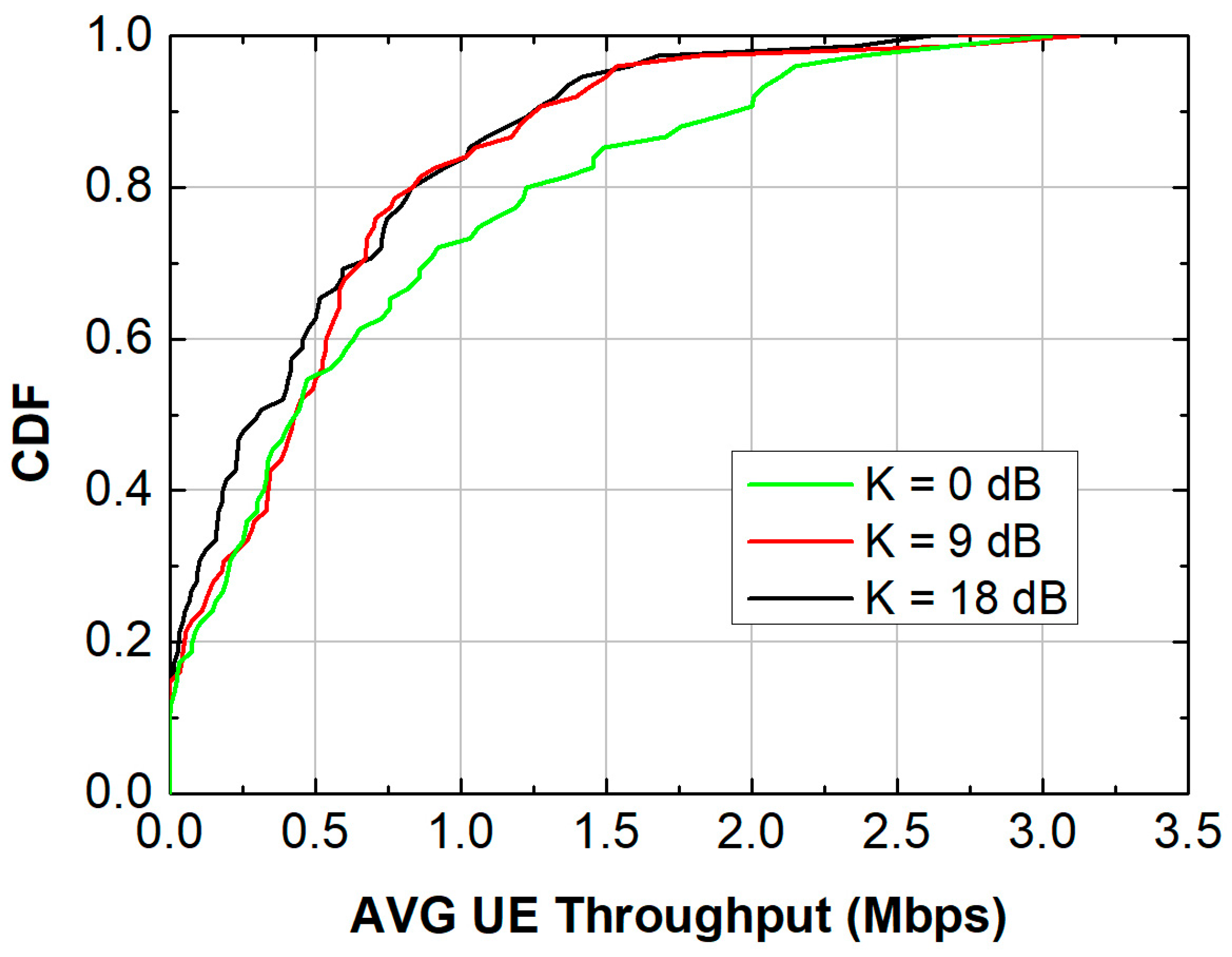

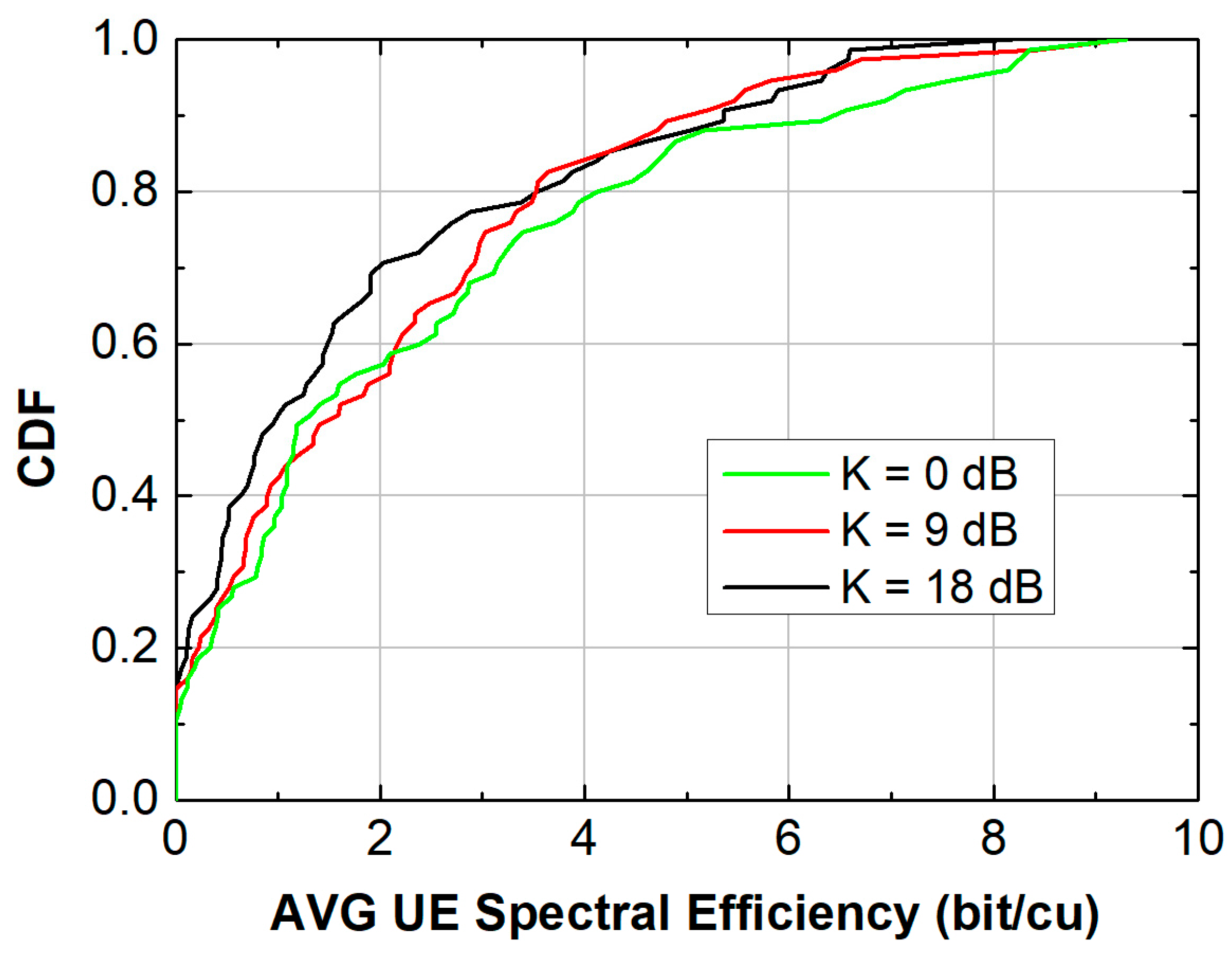

- Simulation 3: Changing K-factor

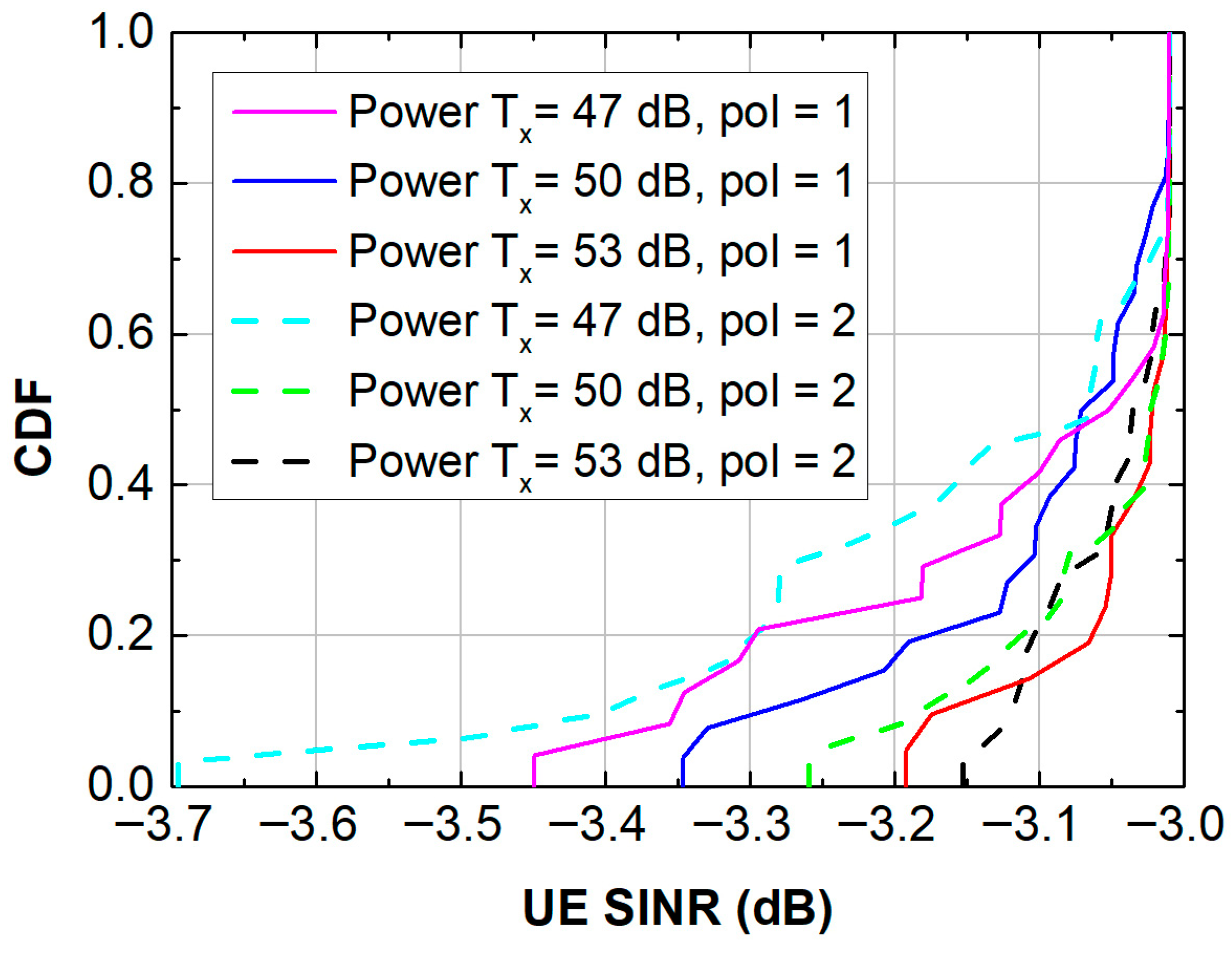

- Simulation 4: Changing Power Transmission and Antenna Polarization

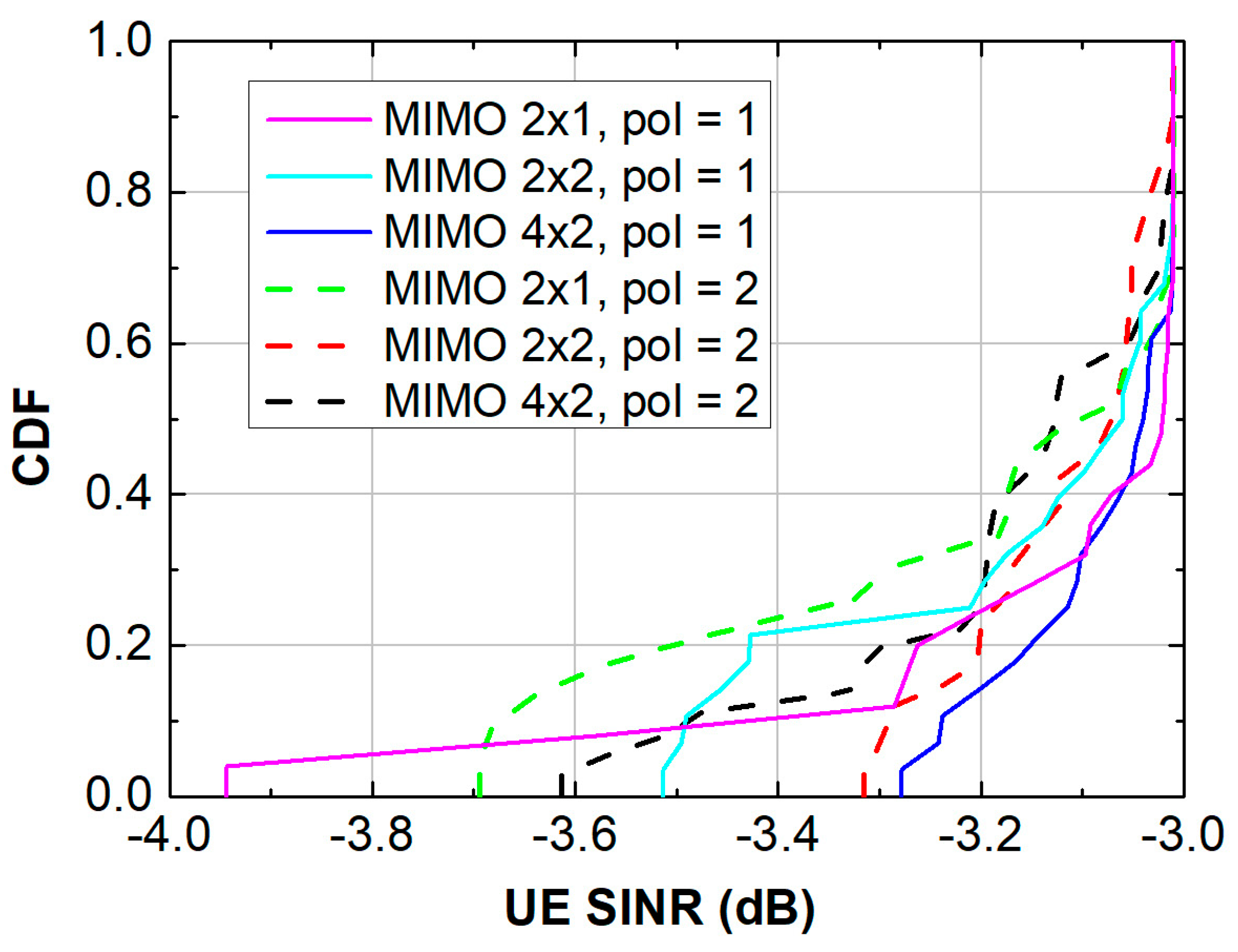

- Simulation 5: Changing Antenna Elements and Polarization

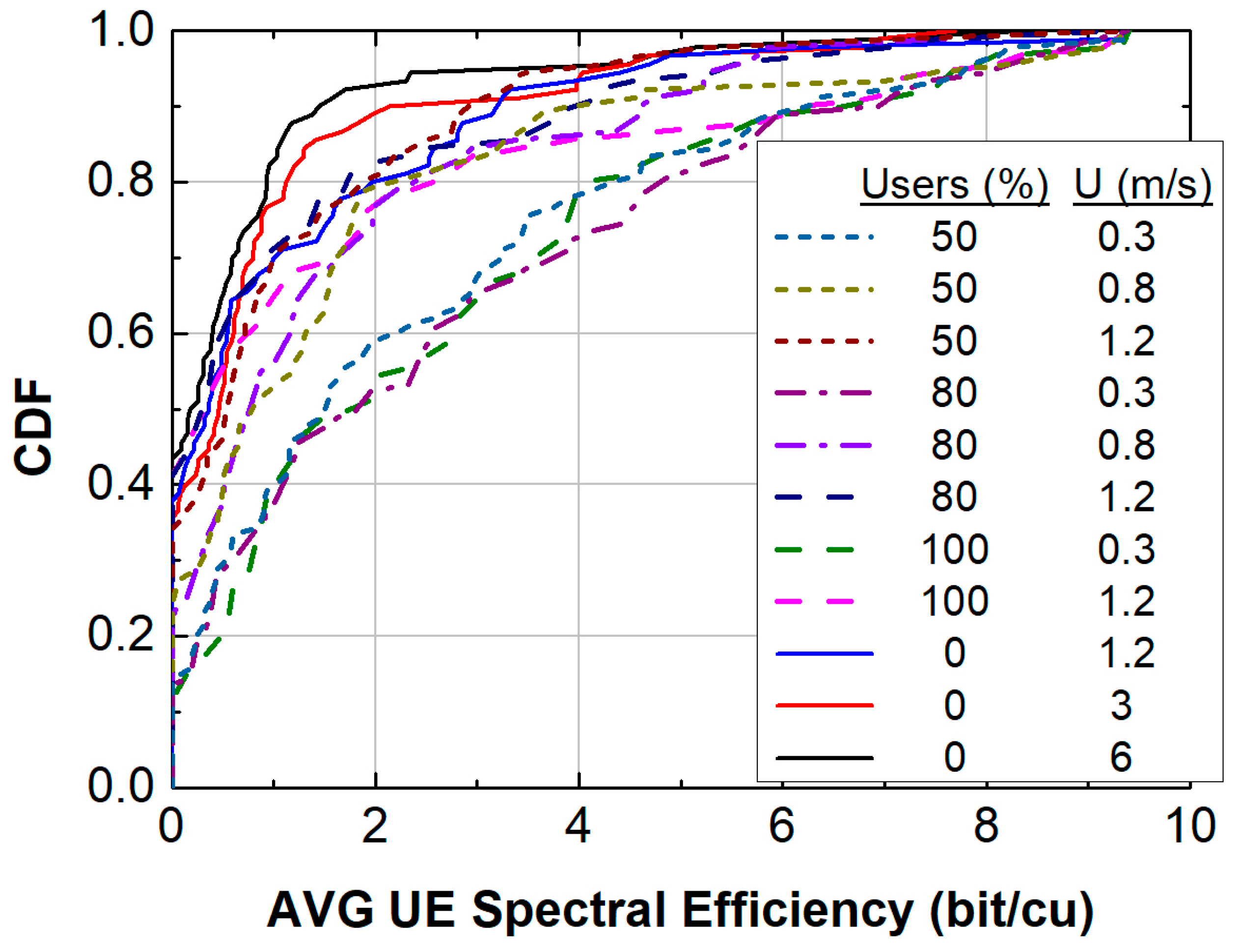

- Simulation 6: Adding Velocity to users and changing the indoor fraction

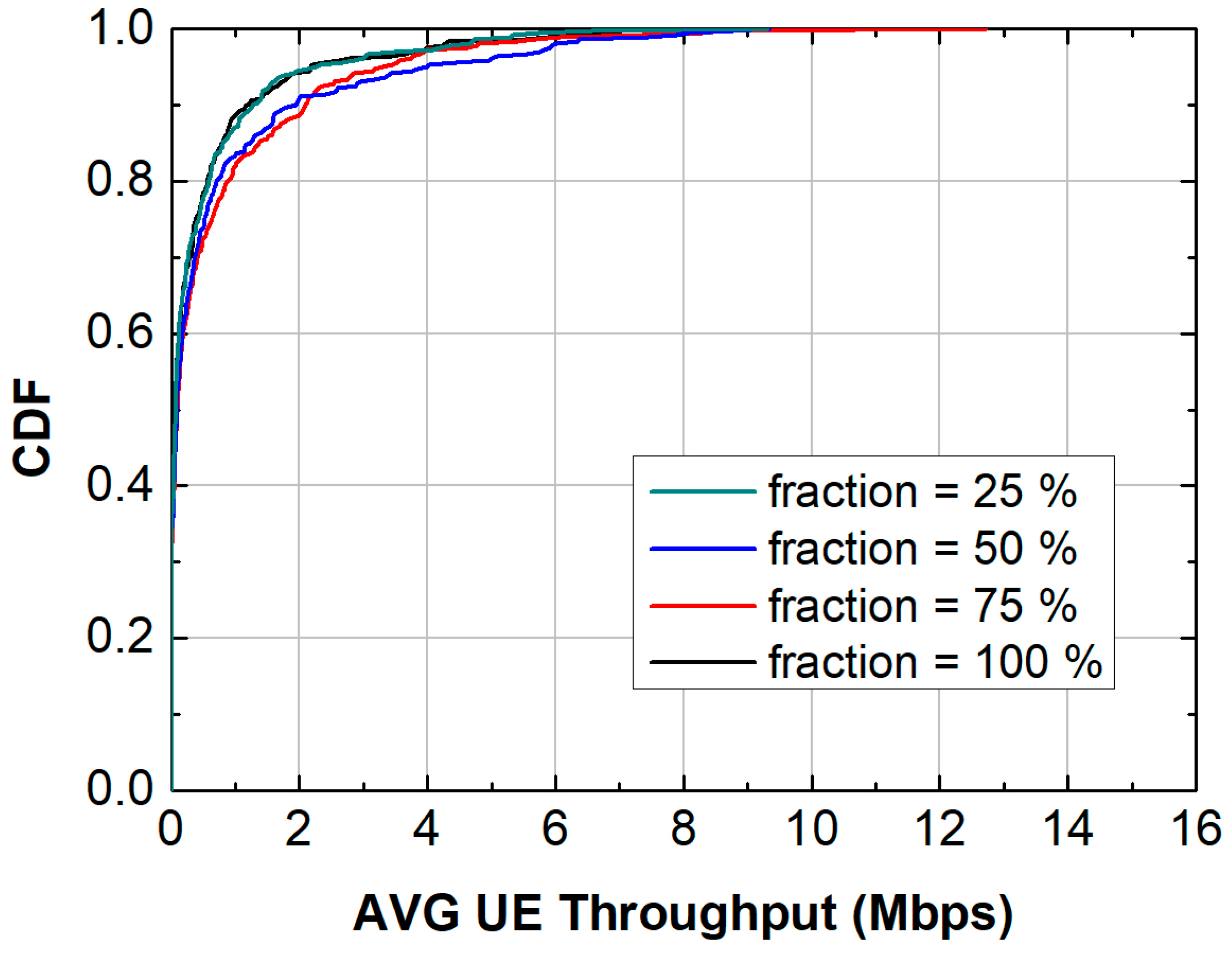

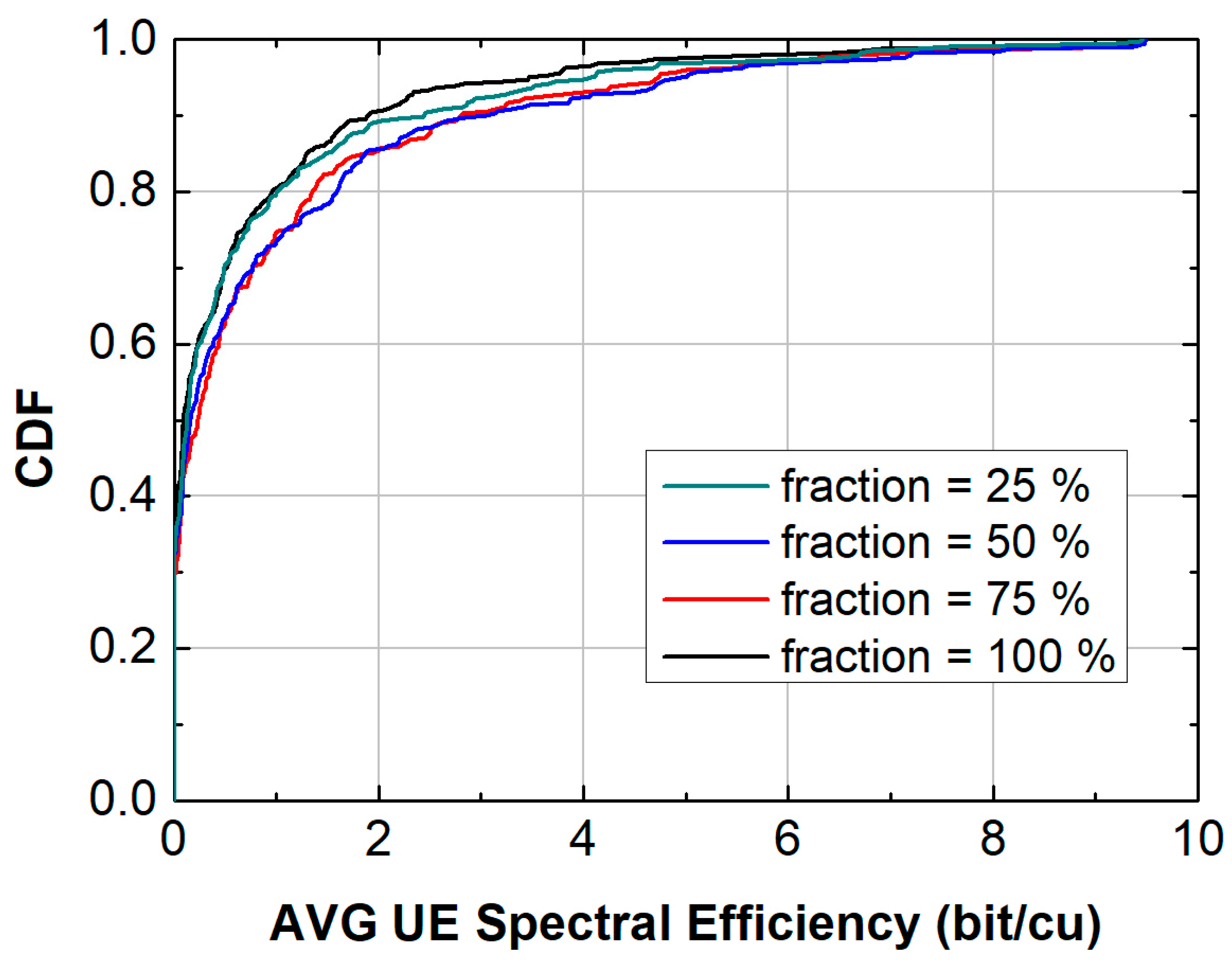

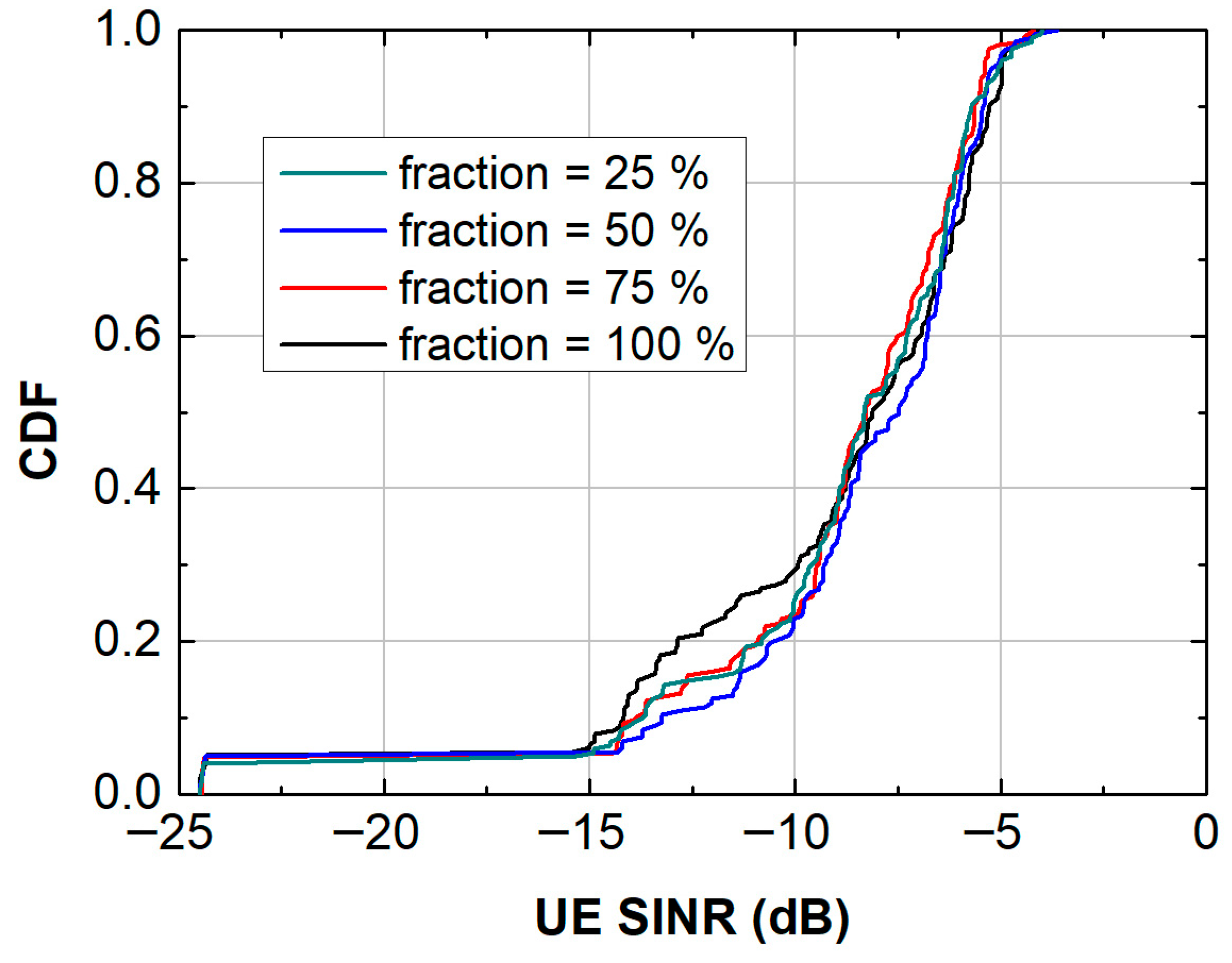

- Simulation 7: Changing our model to indoor situations

- Symmetry Measurement Approach

- Variance (σ2) of Average Spectral Efficiency

- Avg UE spectral efficiency for the i-th user or scenario;

- is the mean of all values;

- number of users or scenarios considered;

- variance, which quantifies the spread of values around the mean.

- is the variance of average UE spectral efficiency across users or scenarios

- = Avg UE spectral efficiency of the i-th user or scenario;

- is the mean value;

- number of users or scenarios considered;

- small number (e.g., 1 × 10−6) to avoid division by zero [27].

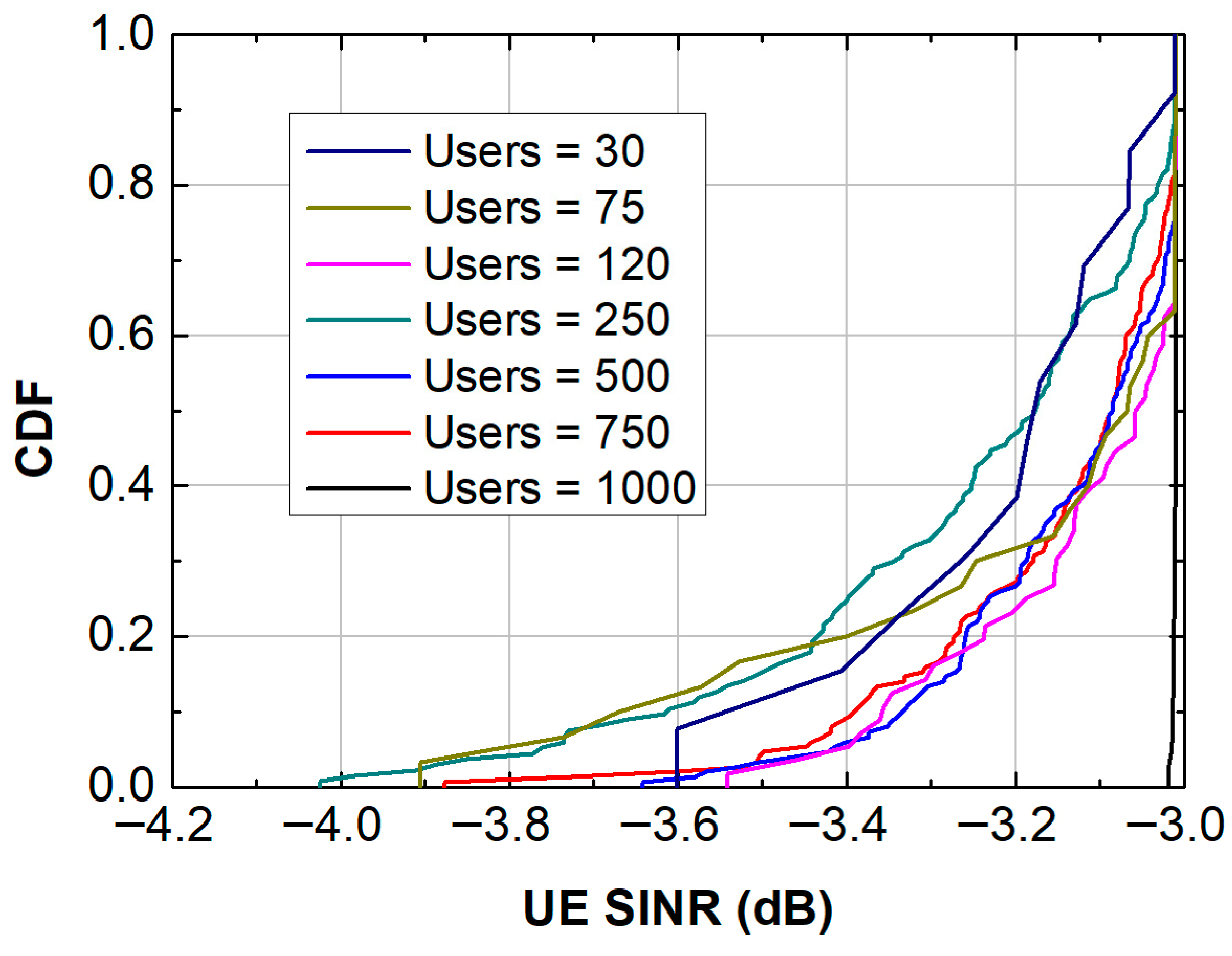

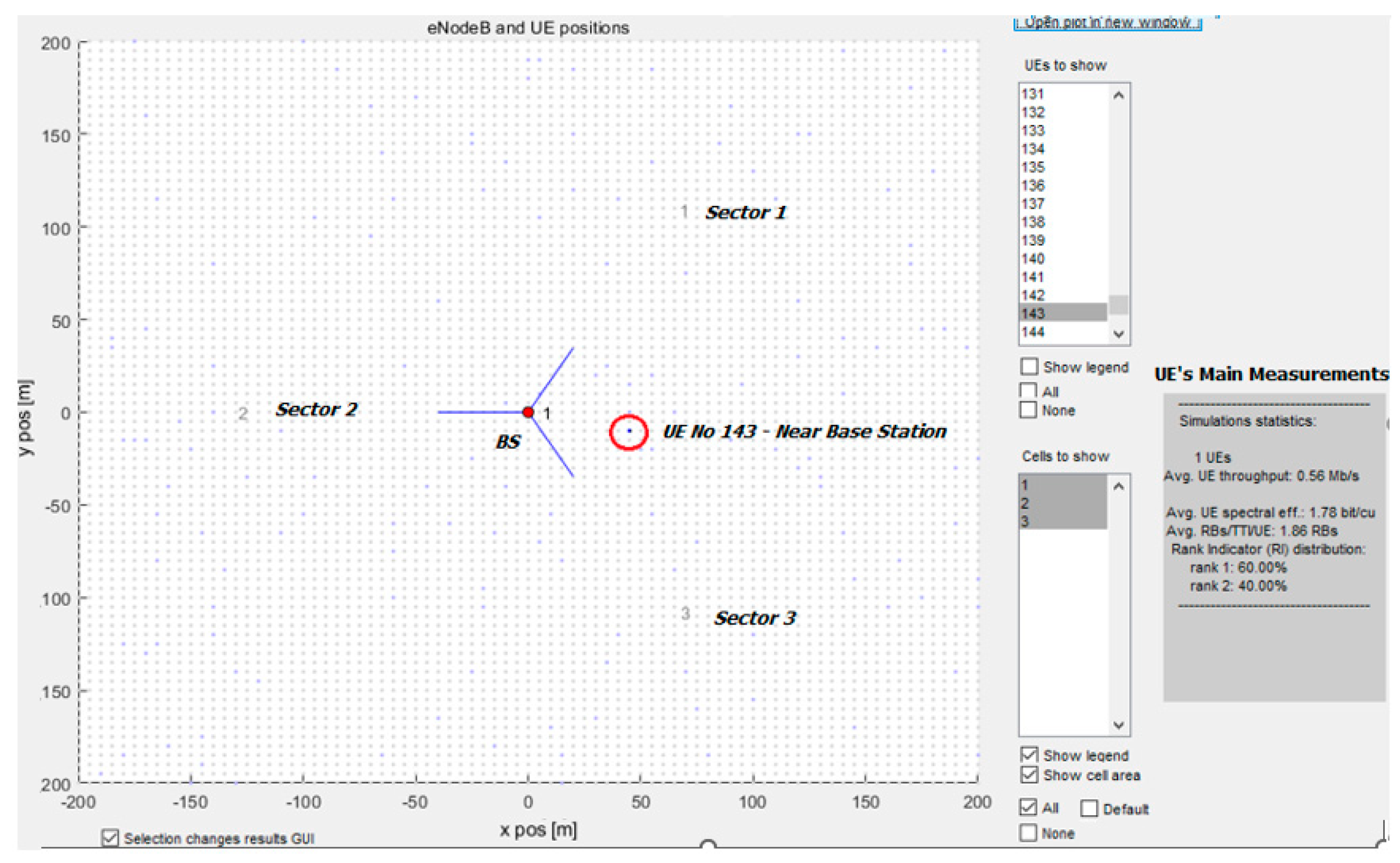

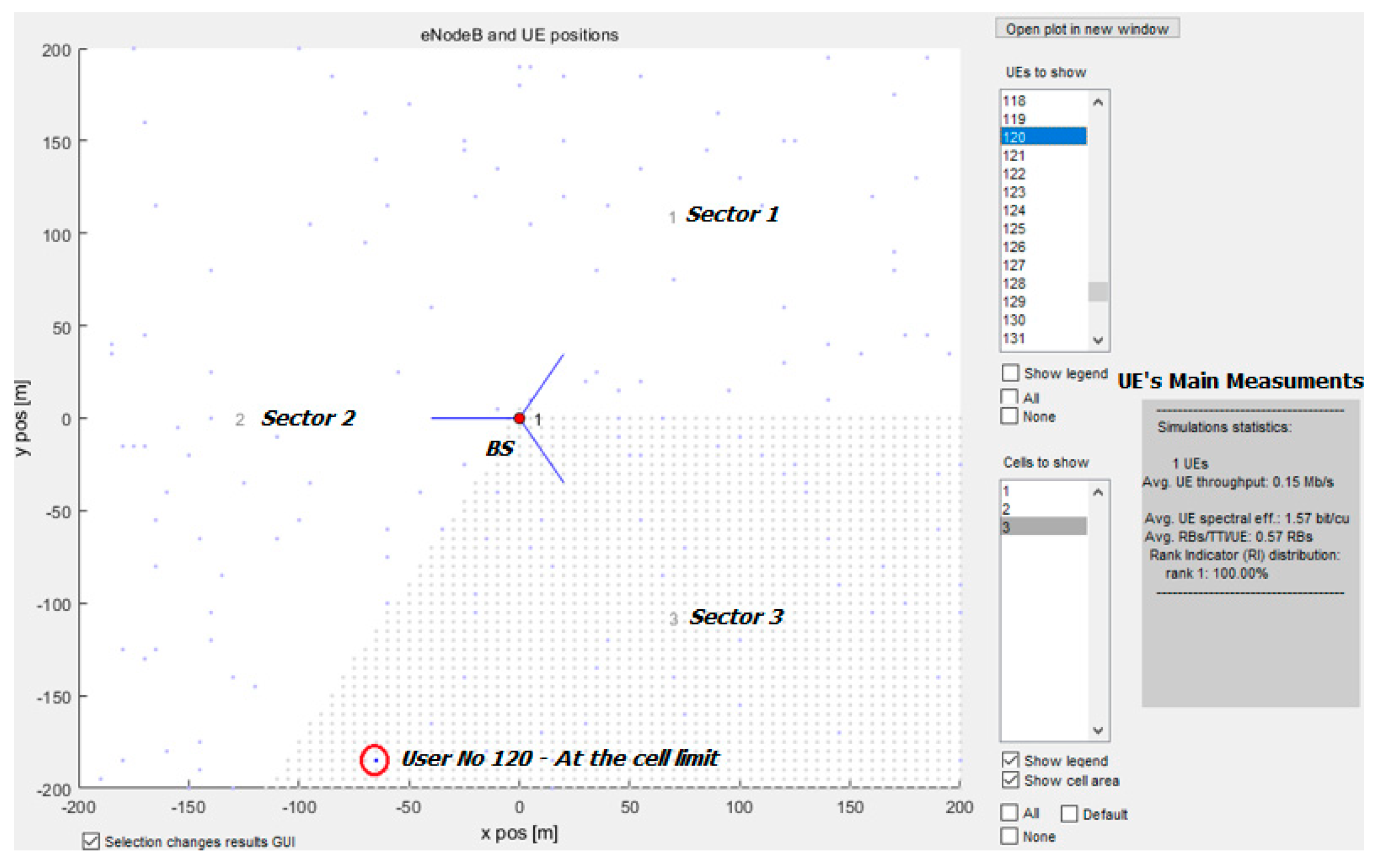

- Simulation 8: Increasing Users

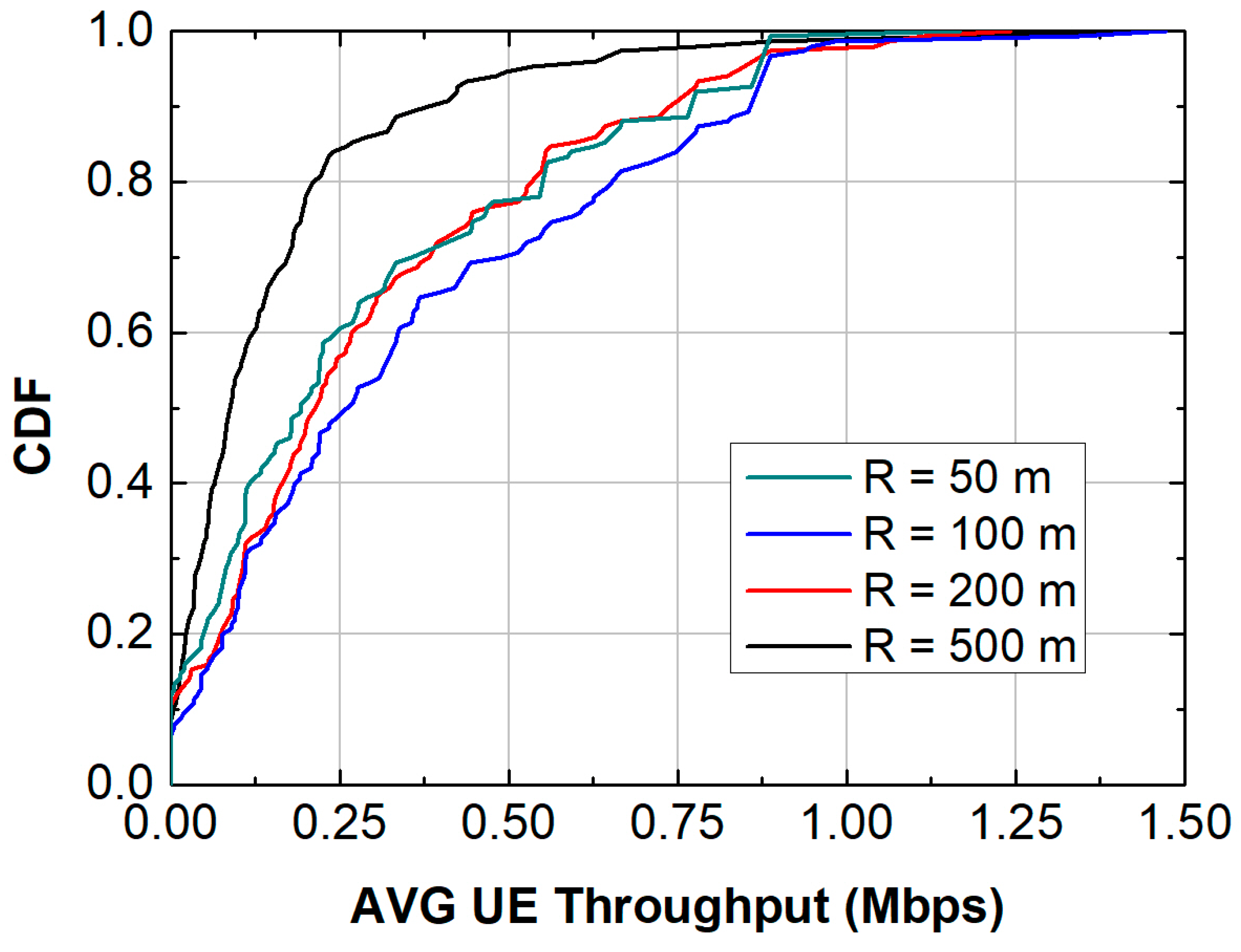

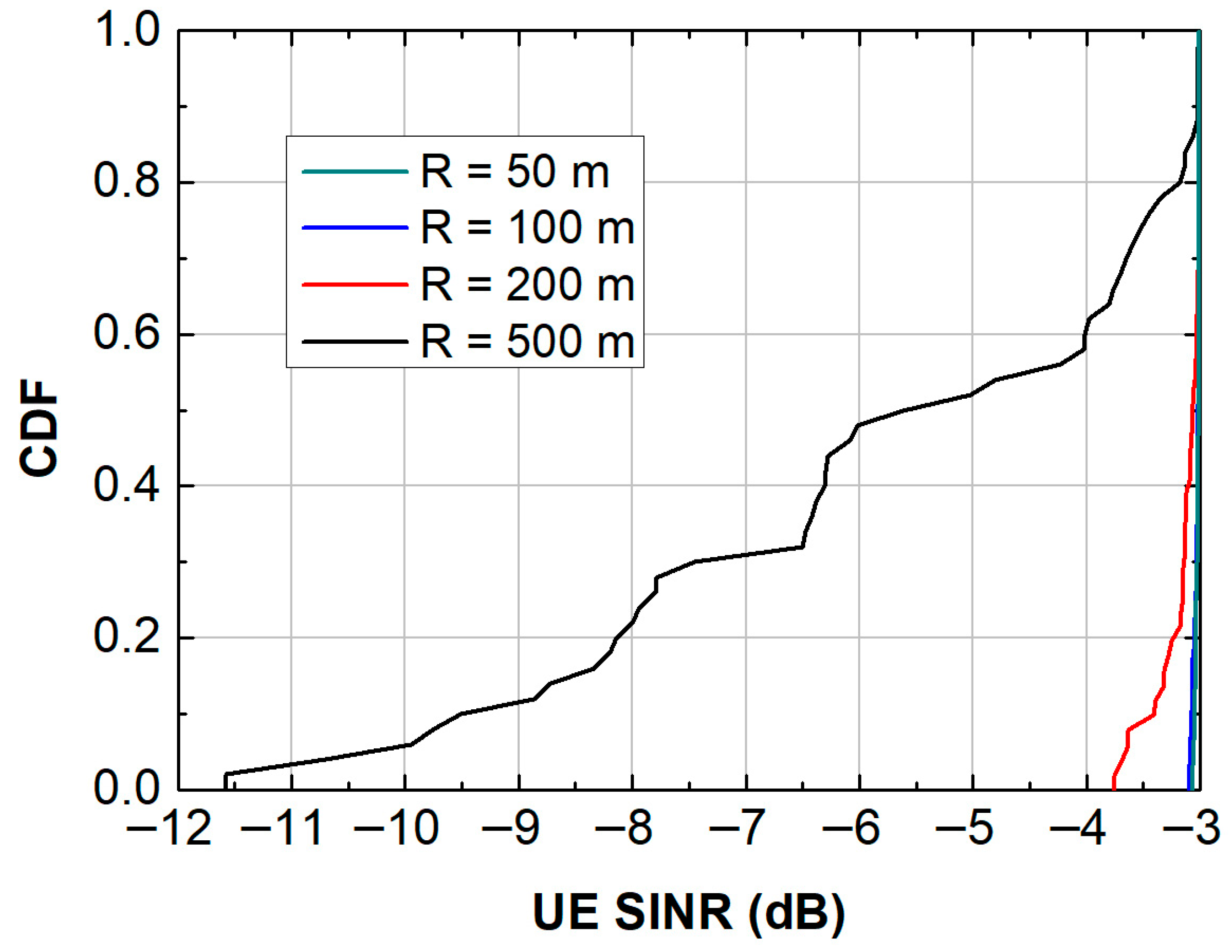

- Simulation 9: Increasing Cell Radius

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed Solyman, A.A.; Yahya, K. Evolution of wireless communication networks: From 1G to 6G and future perspective. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 2023, 3943–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.A.; Alsajri, A.; Kalakech, A.; Steiti, A. Difference between 4G and 5G networks. Babylon. J. Netw. 2023, 2023, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kaur, G. Advancements and impact of 4G communication: A technological revolution. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2019, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Hanzo, L. Fifty years of MIMO detection: The road to large-scale MIMOs. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 1941–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Srivastava, G.; Khandelwal, M.K.; Roges, R. Design Challenges and Solutions of Multiband MIMO Antenna for 5G/6G Wireless Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Prog. Electromagn. Res. B 2024, 104, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.I.; Faruk, N.; Atayero, A.A.; Oshin, M.A.; Bello, O.W.; Mutafungwa, E. Radio Access Technologies for Sustainable Deployment of 5G networks in emerging markets. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2017, 12, 14154–14172. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, K.; Haustein, T.; Barbarossa, S.; Strinati, E.C.; Clemente, A.; Destino, G.; Heath, R.W., Jr. Where, when, and how mmWave is used in 5G and beyond. IEICE Trans. Electron. 2017, 100, 790–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Yuan, S.S.A.; Huang, C.; Zhang, J.; Bader, F.; Zhang, Z.; Muhaidat, S.; Debbah, M.; Yuen, C. Electromagnetic channel modeling and capacity analysis for HMIMO communications. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025, 24, 4500–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, J.W.; Qi, Z.J.; Wu, H.T.; Shao, R.W.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Dai, L.; Cui, T.J. A physics-based perspective for understanding and utilizing spatial resources of wireless channels. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.06115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.K.; Ademaj, F.; Dittrich, T.; Fastenbauer, A.; Ramos Elbal, B.; Nabavi, A.; Nagel, L.; Schwarz, S.; Rupp, M. Flexible multi-node simulation of cellular mobile communications: The Vienna 5G System Level Simulator . EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafi, H.; Brik, B.; Frangoudis, P.A.; Ksentini, A.; Bagaa, M. Split federated learning for 6G enabled-networks: Requirements, challenges, and future directions. IEEe Access 2024, 12, 9890–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-C.; Sheen, W.-H.; Wu, M.-Y.; Yeh, T.-Y. Theory and Implementation of a Three-Dimensional Spatial Channel Model for the 3GPP TR 36.873 Long-Term Evolution System. DEStech Trans. Eng. Technol. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.X.; Hua, B.; Mao, K.; Jiang, S.; Yao, M. 3GPP TR 38.901 channel model. In the Wiley 5G Ref: The Essential 5G Reference Online; Wiley Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Salahat, E.; Kulaib, A.; Ali, N.; Shubair, R. Exploring Symmetry in Wireless Propagation Channels. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Networks and Communications (EuCNC), Oulu, Finland, 12–15 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khamayseh, Y.; Al-Qudah, R. Performance of symmetric and asymmetric links in wireless networks. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2022, 12, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviello, D.G.; Di Stasio, F.; Tuninato, R. Performance analysis of multi-user MIMO schemes under realistic 3GPP 3-D channel model for 5G mmwave cellular networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhamani, C.; Roslee, M.; Chuan, L.L.; Waseem, A.; Osman, A.F.; Jusoh, M.H. Performance Analysis of a Millimeter Wave Communication System in Urban Micro, Urban Macro, and Rural Macro Environments. Energies 2023, 16, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, F.E.; Onwuka, E.N.; Salawu, N.; Oyewobi, S.S.; Djouani, K.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. Performance of Path Loss Models over Mid-Band and High-Band Channels for 5G Communication Networks: A Review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-G.; Cho, Y.J.; Oh, T.; Lee, Y.; Chae, C.-B. Relationship between cross-polarization discrimination (XPD) and spatial correlation in indoor small-cell MIMO systems . IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 7, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdogan, Ö.; Björnson, E. Massive MIMO with dual-polarized antennas. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 1448–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Xu, P.; Guo, X. MIMO system capacity based on different numbers of antennas. Results Eng. 2022, 15, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ai, B.; Zhang, J. Downlink spectral efficiency of massive MIMO systems with mutual coupling. Electronics 2023, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Pei, Q.; Liu, F.; Li, B. A comparative measurement study of cross-layer 5G performance under different mobility scenarios. Comput. Netw. 2024, 257, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokin, G.; Volgushev, D. Model for interference evaluation in 5G millimeter-wave ultra-dense network with location-aware beamforming. Information 2023, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Hong, M. Spectral efficiency optimization for millimeter-wave multi-user MIMO systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2018, 12, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, G.V.; Mood, A.M.; Graybill, F.A.; Boes, D.C. Introduction to the Theory of Statistics, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Björnson, E.; Sanguinetti, L.; Hoydis, J.; Larsson, E.G. Massive MIMO Networks: Spectral, Energy, and Hardware Efficiency; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, X.; Lei, X.; Zhang, Y. Spectral-efficient hybrid precoding for multi-antenna multi-user mmWave massive MIMO systems with low complexity. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.A.; Lazarescu, M.T.; Quasso, R.; Lavagno, L. CUDA-Optimized GPU Acceleration of 3GPP 3D Channel Model Simulations for 5G Network Planning. Electronics 2023, 12, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhu, X.; Du, P. A Three-Dimensional Fully Polarized Millimeter-Wave Hybrid Propagation Channel Model for Urban Microcellular Environments. Electronics 2024, 13, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, T.; Ryanu, H.H.; Pramudita, A.A. Effect of antenna polarization arrangement on MIMO channel capacity. Emerg. Sci. J. 2025, 9, 1076–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liew, S.C.; Vucetic, B. Non-Uniform Linear Antenna Array Design and Optimization for Millimeter-Wave Communications. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2016, 15, 7343–7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, D.; Viswanath, P. Fundamentals of Wireless Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, S.; Taranetz, M.; Rupp, M. The Vienna LTE-Advanced Simulators: Design, Implementation and Use; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X. An Approach to Maximize the Admitted Device-to-Device Pairs in MU-MIMO Cellular Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 1198. [Google Scholar]

| Parametres | Value |

|---|---|

| User Density | 2500 users/Km2 |

| User Velocity | 0 |

| Carrier Frequency | 28 GHz |

| TTi | 10 |

| Bandwidth | 10 MHz |

| Subcarrier Spacing | 60 KHz |

| TX Power | 47 dB |

| Polarizations | Single-dual |

| Indoor UTs percentage | 80% |

| UMi—specifications | |

| BS Height | 10 m |

| User Height | 1.5 m |

| Building floor height | 3 m |

| User Velocity | 0 |

| User distribution | 75 users/cell |

| Antenna—specifications | |

| nTx | 4 |

| nRx | 2 |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 1) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| Power Tx = 10 watt | 17.26 | 2.20 |

| Power Tx = 30 watt | 15.62 | 2.15 |

| Power Tx = 50 watt | 19.04 | 2.50 |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 2) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency: 2.4 GHz | 21.34 | 2.86 |

| Frequency: 3.5 GHz | 23.70 | 3.27 |

| Frequency: 5.8 GHz | 33.30 | 3.34 |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 3) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| K-factor = 0 dB | 17.94 | 2.39 |

| K-factor = 9 dB | 14.05 | 2.62 |

| K-factor: 18 dB | 12.51 | 1.84 |

| Channel Specifications (ol = 1: Single Polarization Pol = 2: Dual Polarization) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| Power Tx = 47 db, pol = 1 | 28.01 | 3.93 |

| Power Tx = 50 db, pol = 1 | 26.71 | 3.46 |

| Power Tx = 53 db, pol = 1 | 33.01 | 4.76 |

| Power Tx = 47 db, pol = 2 | 23.62 | 3.04 |

| Power Tx = 50 db, pol = 2 | 24.47 | 3.40 |

| Power Tx = 53 db, pol = 2 | 25.19 | 3.20 |

| Channel Specifications (Pol = 1: Single Polarization Pol = 2: Dual Polarization) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| MIMO 2 × 1, pol = 1 | 14.46 | 2.02 |

| MIMO 2 × 2, pol = 1 | 19.05 | 2.54 |

| MIMO 4 × 2, pol = 1 | 20.35 | 2.96 |

| MIMO 2 × 1, pol = 2 | 16.54 | 2.30 |

| MIMO 2 × 2, pol = 2 | 20.08 | 2.72 |

| MIMO 4 × 2, pol = 2 | 22.32 | 3.03 |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 6) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| Indoor fraction 50%, velocity = 0.3 m/s (1.1 km/h) very slow movement | 15.60 | 2.42 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, velocity = 0.8 m/s (3 km/h) slow movement | 10.92 | 1.67 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, velocity = 1.2 m/s (4 km/h) normal pedestrian | 7.76 | 1.09 |

| Indoor fraction 80%, velocity = 0.3 m/s (1 km/h) very slow movement | 16.80 | 2.67 |

| Indoor fraction 80%, velocity = 0.8 m/s (3 km/h) slow movement | 10.12 | 1.49 |

| Indoor fraction 80%, velocity = 1.2 m/s (4 km/h) normal pedestrian | 7.84 | 1.67 |

| Only Indoor Users, velocity = 0.3 m/s (1 km/h) very slow movement | 18.23 | 2.58 |

| Only Indoor Users, velocity = 1.2 m/s (3 km/h) pedestrian movement | 10.21 | 1.61 |

| Only Outdoor Users, velocity = 1.2 m/s (normal pedestrian) | 8.56 | 1.13 |

| Only Outdoor Users, velocity = 3 m/s (10 km/h—running) | 6.28 | 0.92 |

| Only Outdoor Users, velocity = 6 m/s (20 km/h—bicycling) | 5.17 | 0.70 |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 7) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| Indoor fraction 25%, indoor office model type, soft movement = 0.3 m/s | 4.64 | 0.78 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, indoor office model type, soft movement = 0.3 m/s | 6.83 | 0.98 |

| Indoor fraction 75%, indoor office model type, soft movement = 0.3 m/s | 6.61 | 0.91 |

| Indoor fraction 100%, indoor office model type, soft movement = 0.3 m/s | 4.64 | 0.69 |

| Sim | Scenario | Variance of Avg UE SE (σ2) | CSI | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pol = 1 Tx: 47 → 53 dB | 0.289 | 3.46 | Higher variance → asymmetric channel |

| 1 | Pol = 2 Tx: 47 → 53 dB | 0.022 | 45.45 | Lower variance → improved symmetry |

| 2 | Pol = 1 2 × 1, 2 × 2, 4 × 4 | 0.148 | 6.76 | Higher variance → asymmetric channel |

| 2 | Pol = 2 2 × 1, 2 × 2, 4 × 2 | 0.090 | 11.11 | Lower variance → improved symmetry |

| 3 | Only Indoor | 0.235 | 4.26 | Lower variance → more symmetric among indoor users |

| 3 | Only Outdoor | 0.031 | 32.26 | Lowest variance → very symmetric channel |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 8) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| Indoor fraction 50%, 30 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 28.06 | 3.63 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, 75 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 16.73 | 2.36 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, 120 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 14.27 | 2.25 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, 250 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 17.58 | 2.16 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, 500 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 29.88 | 3.48 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, 750 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 38.51 Average user = 0.15 | 4.40 |

| Indoor fraction 50%, 1000 users per cell (r = 100 m) | 38.91 Average user = 0.13 | 4.97 |

| Channel Specifications (Simulation 9) | Average Cell Throughput (Mb/s) | Avg UE Spectral Efficiency (bit/cu) |

|---|---|---|

| 150 users per cell (cell radium = 50 m) | 14.36 | 2.32 |

| 150 users per cell (cell radium = 100 m) | 14.45 | 2.52 |

| 150 users per cell (cell radium = 200 m) | 12.44 | 2.12 |

| 150 users per cell (cell radium = 500 m) | 7.91 | 1.31 |

| Simulation | Parameter(s) Varied | Observed Effect | Unexpected/Counterintuitive Observations | Symmetry/Asymmetry Impact | Practical Significance/Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Transmit Power (10–50 W) | Higher power generally improves SNR and throughput | 30 W slightly lower throughput than 10 W | Minor impact on symmetry; interference creates uneven gains | Highlights multi-user interactions and power optimization |

| 2 | Carrier Frequency (2.4–5.8 GHz) | Cell throughput increases with frequency | Avg User throughput does not always increase proportionally | Higher frequency can increase asymmetry due to directional propagation and blockage | Frequency selection must consider spatial variability |

| 3 | K-factor (0–18 dB) | Low K → high spatial multiplexing; high K → reduced MU-MIMO gain | Moderate K (~9 dB) sometimes higher spectral efficiency | High LOS improves symmetry but reduces rank; low K balances asymmetry and spatial streams | Trade-off between channel stability and multiplexing |

| 4 | Transmit Power + Antenna Polarization | Higher power improves throughput; dual polarization improves symmetry | Dual polarization not always effective | Dual polarization reduces asymmetry; misalignment limits effect | Careful antenna design and alignment needed in urban scenarios |

| 5 | Number of Antenna Elements + Polarization | More antennas and dual polarization increase throughput | Gains saturate beyond certain counts | Larger arrays reduce asymmetry through spatial diversity | Optimize array size and polarization for reliability and coverage |

| 6 | User Mobility + Indoor Fraction | Higher mobility/ indoor fraction → lower throughput | Minor reductions in low-mobility indoor users | Increased mobility and heterogeneous distribution increase asymmetry | Mobility-aware scheduling and indoor coverage strategies required |

| 7 | Indoor Deployment Model | Higher indoor fraction → more interference, lower throughput | 75% indoor fraction sometimes outperformed 50% | Dense indoor layouts increase asymmetry; careful layout reduces it | Beamforming and environment- specific tuning critical |

| 8 | Number of Users | Moderate load → optimal; very high load → interference | Very high users (750–1000) increased avg throughput | High density increases asymmetry; scheduler balances load | Load-adaptive scheduling leverages multi-user diversity |

| 9 | Cell Radius | Larger cells → increased asymmetry; smaller cells → more uniform | Slight throughput improvement 100 m vs. 50 m | Larger radius amplifies path-loss disparities → asymmetry | Careful microcell planning ensures balanced coverage |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mouziouras, N.; Tsormpatzoglou, A.; Angelis, C.T. Performance Analysis of a MIMO System Under Realistic Conditions Using 3GPP Channel Model. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2159. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122159

Mouziouras N, Tsormpatzoglou A, Angelis CT. Performance Analysis of a MIMO System Under Realistic Conditions Using 3GPP Channel Model. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2159. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122159

Chicago/Turabian StyleMouziouras, Nikolaos, Andreas Tsormpatzoglou, and Constantinos T. Angelis. 2025. "Performance Analysis of a MIMO System Under Realistic Conditions Using 3GPP Channel Model" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2159. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122159

APA StyleMouziouras, N., Tsormpatzoglou, A., & Angelis, C. T. (2025). Performance Analysis of a MIMO System Under Realistic Conditions Using 3GPP Channel Model. Symmetry, 17(12), 2159. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122159