1. Introduction

In recent years, stroke has been a very serious health issue that affect patients in their physical abilities, cognitive functions, emotions, and overall quality of life. It causes paralysis or weakness on one side of the body (hemiparesis) in which patients lose their independence and must rely on caregivers for daily activities, adding financial and emotional burdens to their families. According to the World Stroke Organization [

1], there is nearly 12 million new stroke cases occurring annually worldwide and it remains as the second leading cause of death and the third leading cause of combined death and disability, with its burden rising sharply in recent decades.

In Malaysia, there is a concerning upward trend in total stroke cases in which the total stroke cases rose from 152 cases in 2009 to 2138 cases in 2016, an alarming increase of 1307% according to the National Stroke Registry Malaysia [

2]. From that number, 77.3% of post-stroke patients require rehabilitation therapy, which has proven to be effective in speeding up the recovery of motor functions of stroke patients [

3]. Therefore, robotic exoskeletons have become increasingly influential for rehabilitation and mobility assistance, with the ability to enhance human movement and reduce physical strain for individuals with mobility impairments. These wearable devices, initially developed for industrial applications, have demonstrated significant promise in clinical settings, improving rehabilitation outcomes for patients with physical disabilities [

4,

5]. However, despite the progress, many challenges remain in terms of performance, adaptability, and seamless human–robot interaction. The state-of-the-art exoskeletons have rapidly gained traction in clinical settings due to their demonstrable impacts on rehabilitation outcomes and mobility assistance for individuals with physical impairment [

6,

7,

8]. For instance, Amiri et al. introduced an ANFIS compensator, which dynamically learns and optimizes fuzzy rules through neural networks (NNs), significantly enhancing adaptive compensation for unmodeled dynamics [

9]. They found that while combining fuzzy logic with disturbance observers could effectively compensate for nonlinear disturbances, it was heavily reliant on expert knowledge for constructing the rule base. Veneman et al. [

10] proposed an impedance control strategy for natural human–computer interaction, which required high-precision force sensing that was also susceptible to noise. Their study demonstrated that combining terminal sliding mode control (TSMC) with multi-source sensor fusion could reduce dependence on a single high-precision force sensor. Hasan et al. also employed the Beetle Antenna Search algorithm to improve sit-to-stand trajectory accuracy; however, it requires high computational complexity, which limits its real-time performance [

11,

12].

Durandau et al. [

13] incorporated transmission nonlinearities through a model-based adaptive control into a dynamic model of bilateral ankle exoskeletons that enhanced robustness and compensated unknown disturbances via a sliding mode observer. They employed electromyography (EMG)-biomechanical models that can be adapted to various speeds and slopes, which heavily depends on model identification accuracy [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Furthermore, Ferris and Lewis described proportional myoelectric control for a robotic exoskeleton, where the wearer’s muscle electrical signals facilitate lower limb movement through a physiologically natural strategy. They emphasized that users with incomplete spinal cord injuries exhibit rapid changes in muscle recruitment, suggesting that the EMG-based control method offers distinct advantages over traditional exoskeleton control systems, both for rehabilitation and scientific exploration [

18]. On the other hand, the switching between proportional-integral-derivative (PID)-SMC and fuzzy model predictive control (MPC) strategies was complex and heavily dependent on computational resources [

19,

20]. Their study developed an intelligent switching logic triggered by multi-source sensors, integrating PID and SMC for swing/stance-phase separation. This approach effectively balances real-time performance with multi-degree-of-freedom (DOF) coordination in the lower limb exoskeleton.

Alawad et al. presented an observer-based SMC strategy for lower limb exoskeletons aimed at rehabilitation, addressing resistance to external disturbances and uncertainties in the system’s dynamics. The proposed control method enhances the robustness and stability of exoskeleton-assisted movement, ensuring reliable tracking of desired limb trajectories during rehabilitation exercises [

21,

22,

23]. Tu et al. proposed an adaptive sliding mode variable admittance control technique that dynamically adjusts the robot’s response to the user’s force and movement intentions, improving safety and comfort during lower limb rehabilitation. Their approach demonstrates how adaptive control can accommodate changing patient conditions and interactive forces, leading to more natural and effective rehabilitation outcomes [

24].

Meuleman et al. introduced an innovative robotic gait training system, LOPES II, that featured an admittance control that was designed to provide individualized, task-specific support that promotes natural walking and effective neurorehabilitation for individuals with gait impairment [

25,

26,

27]. The study by Aliman et al. analyzed various actuator types and transmission mechanisms employed in lower limb rehabilitation exoskeletons, highlighting their design principles, performance characteristics, and implications for improving mobility and adaptability in clinical applications [

28]. Amiri and Ramli proposed an admittance swarm-based adaptive controller that focused on the gait trajectory cycles of a rehabilitation lower limb exoskeleton robot. They developed a robust adaptive controller integrated with an admittance model to overcome human–robot interaction forces generated by the wearer [

29].

Based on previous studies, the robotics exoskeletons have emerged as promising tools in rehabilitation for patients with neurological diseases, stroke, or spinal cord injury to regain gait function, improve mobility, and reduce therapist workload. There is a growing demand for lower limb exoskeletons to improve rehabilitation quality, enhance patient motivation, and optimize clinical outcomes in specialized neurological rehabilitation. Also, the challenges faced by physiotherapists are crucial in adopting robotic exoskeletons due to usability, resource, and training limitations, which impact successful clinical integration of these technologies. Furthermore, the control strategies mostly rely on model-based or assist-as-needed approaches that do not fully accommodate the nonlinearities, uncertainties, and external disturbances inherent in human–exoskeleton interaction, which can cause deviations in trajectory tracking and reduce user comfort and safety. Therefore, these are the reasons that motivate our study to improve control strategies and gait switching mechanisms for better performance, adaptability, and acceptance of robotics exoskeletons in the rehabilitation process.

The key contributions and innovations of this study are outlined as follows:

A novel intelligent switching control for a five-bar lower limb exoskeleton has been designed based on the different phases of gait, which are the support phase and swing phase. The support phase is divided into three sub-stages, i.e., pre-support, mid-support, and terminal support.

We propose a hybrid controller that combines proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control and the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) to generate natural and compliant leg movements during the swing phase to compensate the nonlinearity and disturbances of the patients’ movements.

Terminal sliding mode control has been proposed as an amplification controller for the support phase to ensure rapid convergence of the system state to equilibrium within a finite time and guarantee the robustness against parameter uncertainties and external disturbances. This controller is proposed because it is highly suitable for handling the complex human–machine interaction forces and dynamic model variations within the support phase. We also replace the sign function in the switching terms of the classical SMC with the hyperbolic tangent function to guarantee the continuity of torque variations.

The content of this paper is as follows.

Section 1 introduces the existing research methods of exoskeletons.

Section 2 details the dynamic modeling of the exoskeleton linkage mechanism.

Section 3 introduces the control methods of the support phase and swing phase of the exoskeleton linkage mechanism.

Section 4 summarizes the research results and

Section 5 concludes our findings and future research directions.

2. Dynamic Modeling of Exoskeleton Linkage Mechanism

In this paper, human movement is simulated and supported by a five-bar linkage model of a robotic exoskeleton, which is based on the connection of five key points forming a framework to mimic the motion of human joints. These five key points represent the main connection points of the exoskeleton system, such as the hip, knee, ankle, and other possible joints. The five assumptions are made to ensure the feasibility of the dynamic model and focus on the core control issues: (1) all linkages are rigid bodies, (2) all joints are frictionless ideal revolute pairs, (3) the system moves in the sagittal plane, (4) the mechanism has structural symmetry, and (5) the mass parameters of the linkages (mass, center of mass, and moment of inertia) are concentrated and known. The dynamic model of the symmetrical five-bar exoskeleton was derived based on the standard Lagrangian formula for rigid multi-body systems adopted from Bajrami et al. [

30]. The exoskeleton linkage dynamics model is shown in

Figure 1, where

,

, and

are the support phase parts, while

and

are the swing phase parts.

From the model of the exoskeleton linkage system shown in

Figure 1, we established its dynamics equation. The support stage is divided into three sub-stages: pre-support, mid-support, and terminal support. The dynamic model equation of the support phase is expressed as:

where

,

, and

are the joint angles, velocities, and accelerations of the support sections, respectively.

represents the support phase inertia matrix, which is divided into the inertia matrix of the mid-support phase

and the inertia matrices of the pre-support and terminal-support phases

. The support phase centrifugal force and Coriolis force matrix,

, is divided into the mid-support inertial phase Coriolis force matrix

and the pre-support and terminal-support phase Coriolis force matrix

.

is the support phase gravity matrix, and

is the generalized moment of each joint of the support phase.

The mathematical expression of the inertia matrix for the mid-support phase in Equation (1) is expressed as:

and the centrifugal force and Coriolis force matrix of the mid-support phase are denoted by:

Also, the gravity matrix of the mid-support phase is represented by:

The inertia matrices for the pre-support phase and the terminal-support phase can be expressed in Equation (1) as follows:

and the centrifugal force and Coriolis force matrix of the pre-support phase and the terminal-support phase are denoted by:

The pre-support phase, the terminal-support phase, and the mid-support phase have the same form of gravitational matrix.

The swing phase dynamic model equation is represented as follows:

where

,

, and

are the joint angles, velocities, and accelerations of the swing sections, respectively.

represents the swing phase inertia matrix,

is the swing centrifugal force and Coriolis force matrix,

is the support phase gravity matrix, and

is the generalized moment of each joint of the swing phase.

In Equation (7), the swing phase of the inertia matrix is defined as:

and the oscillating centrifugal force and Coriolis force matrix is represented by:

The gravity matrix of the oscillating phase is defined as:

The structure of our dynamic model, particularly the formulation of the inertia and Coriolis matrices, aligns with the established dynamics for five-bar parallel mechanisms, as detailed in studies such as [

31,

32]. The model parameters are shown in

Table 1.

3. Switching Control Mechanism of Exoskeleton Linkage

The gait phase is defined by the pressure signals on the sole of the foot. The support phase consists of three sub-phases: pre-support, mid-support, and final support, which, respectively, perform the functions of stable landing, main support, and smooth transition. The swing phase begins when the heel leaves the ground (pressure < ) and ends when the heel touches the ground (pressure > ), and it is realized with PID-ANFIS for smooth swinging. Each phase is seamlessly connected through an intelligent switching algorithm.

3.1. Support Phase Control

The support phase control of the exoskeleton linkage mechanism focuses on the dynamic management of the exoskeleton system during the support phase, aiming to achieve a stable, balanced, and efficient support process to support the user walking and standing.

Position tracking control of the exoskeleton support phase is a key component of exoskeleton technology, which is of great significance to improve the functionality and practicability of the robotic exoskeleton system.

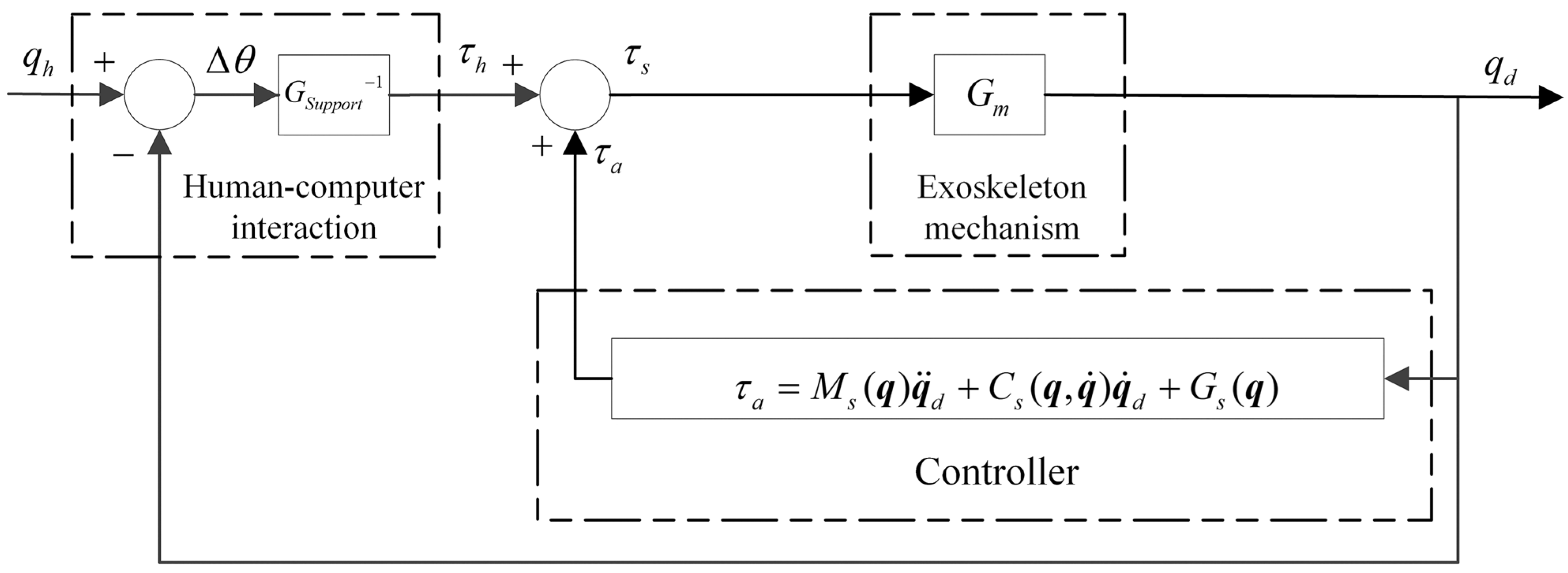

Figure 2 shows the block diagram of the position tracking control for the exoskeleton mechanism outside the support phase.

represents the desired joint trajectory of the support phase,

represents the output trajectory,

represents the error between desired and output trajectory,

represents human–machine interaction torque, and

denotes the input of the control system.

is the output torque of the controller.

is the transfer function of the human–machine interaction module,

is the component that provides the equivalent rotational inertia of the system, and

is the equivalent damping of the support phase.

is the transfer function of the exoskeleton mechanism,

represents the equivalent rotational inertia of the lower limbs of the human body and the exoskeleton,

denotes the damping coefficient, which reflects the viscosity of the joint, and

is the stiffness coefficient and reflects the elasticity of the joint.

3.1.1. Support Phase Sensitivity Amplification Control Form

To optimize the control strategy of the support phase, this study subdivides the support phase into three sub-phases: pre-support, mid-support, and terminal support, with distinct control methods designed for each phase. In the pre-support phase, SMC is employed to ensure stable support as the foot prepares to contact the ground. In the mid- support phase, a PID-ANFIS hybrid control approach is applied to provide maximum support while maintaining joint stability. During the terminal-support phase, an intelligent switching control strategy is utilized, gradually reducing the torque amplification ratio to facilitate a smooth transition to the swing phase.

The output torque

of the pre-support, mid-support, and terminal-support phase sensitivity amplification controller is shown as the following equations:

where

is the desired trajectory. The output torque of the pre-support and terminal-support phases is represented by Equation (11), while the output torque of the mid-support phase is denoted by Equation (12). Next, the output torques

for the pre-support, mid-support, and terminal-support phases of the human–computer interactions are defined as:

The output torque of human–computer interaction for the pre-support and terminal-support phases is represented by Equation (13), while the output torque of human–computer interaction for the mid-support phase is denoted by Equation (14). In the control process during the support phase of the robotic exoskeleton, as the joint angle of the mechanism converges to the desired trajectory angle , the driving torque exerted by the user approaches zero. By implementing a position tracking controller, it is possible to achieve the objective of minimizing human-applied torque to zero.

3.1.2. Support Phase Sensitivity Amplification Controller

In this paper, we propose a terminal sliding mode control (TSMC) as the amplification controller for the support phase. Terminal SMC is an advanced sliding mode controller specifically designed for nonlinear systems. It not only ensures rapid convergence of the system state to equilibrium within a finite time but also exhibits inherent robustness against parameter uncertainties and external disturbances. This makes it highly suitable for handling the complex human–machine interaction forces and dynamic model variations within the support phase. To guarantee the continuity of torque variations, the sign function in the switching terms of the classical SMC is replaced by the hyperbolic tangent function. Additionally, we propose two fundamental assumptions: first, the derivative of the desired trajectory exists; second, the lumped disturbance of the system is bounded under conditions of imprecise model parameters and the presence of external disturbances. The trajectory error is defined as follows:

and the terminal sliding mode surface is defined as:

In Equation (18), the function

is specifically designed to achieve finite-time convergence and to avoid control singularity. The function

is designed in the form of

. p and q are coprime positive odd numbers, and 1 < p/q < 2. This ensures that the system state has a faster convergence speed than the linear sliding mode when approaching the equilibrium point, and its derivative is zero at the equilibrium point. This characteristic effectively avoids the control singularity problem that may occur in traditional terminal sliding modes. Taking the derivative of Equation (17) yields:

The joint angle

can be measured using sensors, and the real-time calculations are performed to obtain the joint angular velocity

. Let us assume that

in Equation (19) and the equivalent control rate of the sensitivity amplifier controller can be obtained as:

where

is the equivalent control torque of the sliding mode control,

is the switching control torque of the sliding mode control,

is the final output torque, and

denotes the switching item gain.

3.1.3. Stability Verification of the Support Phase Sliding Mode Control Method

The stability of the sensitivity amplifier controller with sliding mode control is verified by using the Lyapunov function candidate. Assuming that the total disturbances (including unmodeled dynamics and external disturbances) existing in the system are bounded, that is, there exists a positive constant

such that

, let us take the Lyapunov function as:

Equation (23) defines the Lyapunov candidate function

, which represents the system’s energy on the sliding surface. The derivative of Equation (23):

where

and

are the design parameters of the controller, and

indicates how the controller dissipates the system’s energy to ensure convergence.

Based on the properties of vector inner product and assumption 1, we can obtain:

Equation (25) introduces the bounded disturbance assumption

, ensuring that all unmodeled dynamics and external perturbations remain within a finite range. For any vector

, there exists a constant

such that the following inequality holds:

The inequality in Equation (26) utilizes the property of the hyperbolic tangent function to approximate the sign function continuously, thereby reducing chattering in the control output. This relation holds because the function is an odd function, and when , . In the vector case, this term is positive definite and of the same order as .

Substitute Equation (26) into Equation (25):

Equation (27) demonstrates that the Lyapunov derivative

is strictly negative if the control gain

k satisfies

, guaranteeing system stability. The finite-time convergence condition is to select the controller gain

such that it satisfies

. We define

. Thus, we have:

Equation (28) expresses the finite-time convergence condition, showing that the sliding variable

and tracking error

converge to zero within a bounded time. Since

, we have

. Substituting it into Equation (28), we obtain the key condition for finite-time stability:

Equation (28) is a standard finite-time convergent differential inequality. By integrating the above inequality, it can be proved that the sliding mode variable

will converge to zero within a finite time

, and the upper bound of the convergence time is:

where

represents the initial value of the Lyapunov function.

Once the system state reaches the sliding surface within a finite time , its dynamics will be governed by the terminal sliding surface defined by Equations (17) and (19). It can be proved that on this sliding surface, the tracking error and its derivative will converge to zero within a finite time. Therefore, the entire closed-loop system is finite-time asymptotically stable.

3.2. Swing Phase Control

The swing phase control of the exoskeleton linkage mechanism is a control strategy that has been widely applied in robot exoskeleton systems. The swing phase control method is specifically designed to control the movement of the internal linkage components of the five-bar exoskeleton, in order to generate precise and coordinated swing trajectories during the gait process.

In this paper, our primary objective of using the swing phase control is to achieve smooth synchronization between the exoskeleton’s swinging action and the user’s own walking dynamics. This synchronization is critical to ensure that the exoskeleton’s assistance is not only smooth and continuous but also adaptively tuned to the user’s intentions and biomechanical needs. The swing phase control strategy is assumed to contribute to a more natural and fluid gait that can enhance the wearer’s comfort, mobility, and overall walking efficiency. Moreover, effective swing phase control is expected to improve the power assistance delivered during the swing phase, reducing muscular effort and fatigue, and potentially expanding the exoskeleton’s applicability in rehabilitation and mobility augmentation contexts.

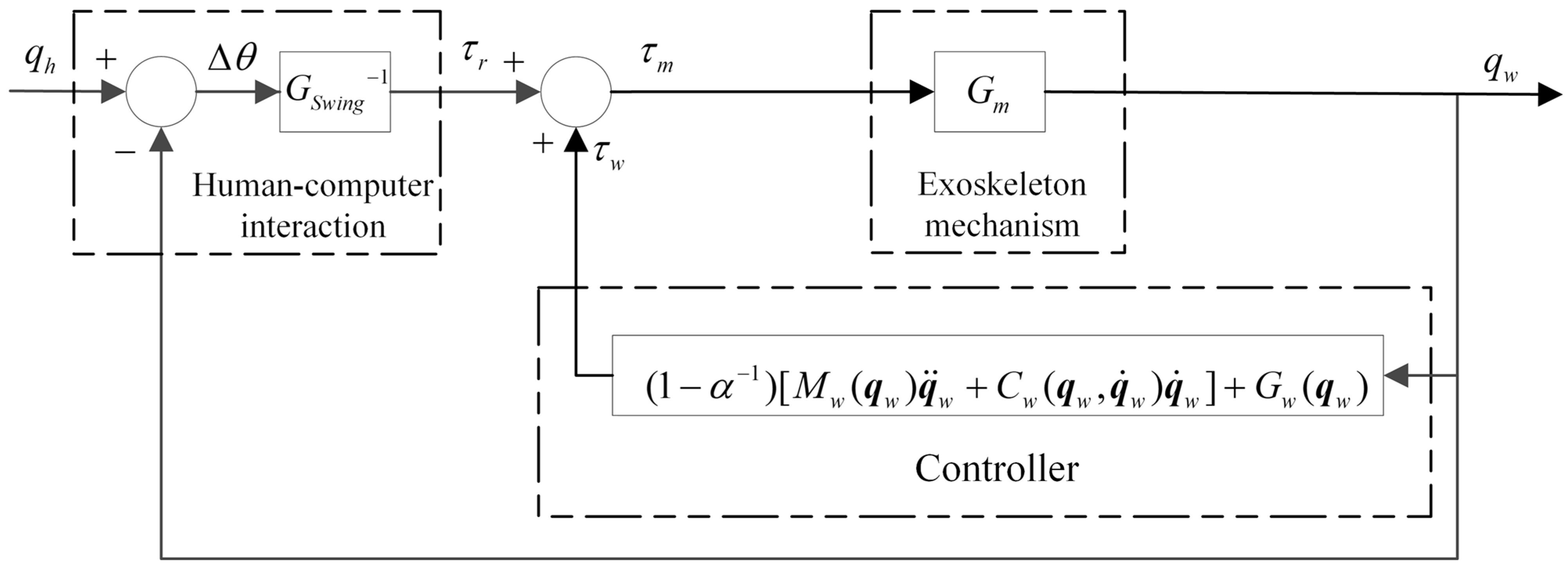

Figure 3 shows the block diagram of the position tracking control for the exoskeleton mechanism outside the swing phase.

represents the desired joint trajectory angle of the swing phase,

represents the measured output trajectory angle,

represents the error between the desired and output trajectories,

represents human–machine interaction torque, and

denotes the input of the control system.

is the output torque of the controller,

is the transfer function of the human–machine interaction module,

represents the equivalent rotational inertia of the oscillating system, and

denotes the equivalent damping in the oscillation phase.

is the transfer function of the exoskeleton mechanism, and its specific form is the same as described above.

is referred to as the torque attenuation factor.

3.2.1. Swing Phase Sensitivity Amplification Control Form

Based on the assumption that the real exoskeleton joint is fitted with an angular displacement encoder to measure angle and force sensors to measure torque, we established the dynamic of the swing phase sensitivity amplification controller.

During the swing phase, the torque after passing through the sensitivity amplification controller is expressed as

, and the torque after the human–computer interaction is expressed as

. The details are as follows:

The core function of is to proportionally reduce the amplitude of the human–machine interaction torque during the swing phase, thereby generating a scaled-down expected torque for motion tracking.

If is too close to 1, the assisting effect will be weak. If is too close to 0, it may cause instability in the system due to excessive amplification of the control effect. During the gait walking, the goal is for the exoskeleton to follow the human motion, requiring continuous adjustments throughout the movement to ensure that the position tracking error consistently converges to the desired angle error. The function of the sensitivity amplification controller is to magnify minute changes in the input signal to a level sufficient to drive the actuator, enabling the system to respond rapidly and accurately to external disturbances or other environmental factors. In the simulation of this study, after comprehensive consideration, we chose = 0.15 to achieve a significant assisting effect while ensuring the stable operation of the system.

3.2.2. Swing Phase Sensitivity Amplification Controller

According to the unique requirements of each gait phase, different control architectures were adopted. During the swing phase, a system combining a PID controller and an ANFIS compensator ensured precise and adaptive trajectory tracking. The PID provided a stable control foundation, while the ANFIS dynamically compensated for nonlinearity and disturbances based on the patient’s movements. The SMC works well for the support phase, where stability is crucial and the system needs to handle external disturbances. The reason for adopting SMC is because of its capability of attenuating the chattering phenomenon, which is the main obstacle for practical SMC applications [

33,

34].

In this paper, the design of the amplification controller adopts the classic control method by using the PID controller as the amplification controller. The error of the PID controller is represented by:

The torque output of the PID controller is defined by selecting appropriate proportional gain, integral gain, and derivative gain, as follows:

where

is the proportional gain,

is the integral gain, and

is the derivative gain.

3.2.3. Stability Verification of the Swing Phase PID Control Method

The stability of the PID controller is evaluated using the root locus method. This model is derived by linearizing around the nominal operating point of the nonlinear oscillation stage dynamics (Equation (7)), which is the middle position of the oscillation, where the joint velocity is zero and the gravitational force is balanced.

The linearized equation of motion for a single joint can be expressed as:

where

,

, and

are the effective inertia, damping, and gravity stiffness terms, respectively, obtained from the linearized matrices in Equations (8)–(10). Δ denotes small deviations from the nominal operating point.

The resulting single-input-single-output (SISO) plant transfer function

from torque input

to joint angle output

is:

The PID controller in the Laplace domain is:

The open-loop transfer function for the root locus analysis is, therefore:

Figure 4 shows the root locus plots for both the

X-axis and

Y-axis, demonstrating how the system poles vary with different PID parameters. By carefully tuning the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, all poles are confirmed to remain in the left half-plane for these two primary motion axes. The results show that the PID controller maintains stable performance in both X and Y directions, and the designed controller parameters ensure system stability during operation.

3.2.4. Compensator Based on ANFIS and the Least Square Method

Due to the strong nonlinearity of the parameters of the robot dynamics model, ANFIS is adopted to compensate for the uncertain parameters of the dynamics model and the influence of external disturbances to improve the model accuracy. According to the dynamic model, the equation of joint axis 1 can be obtained:

Let us assume that

,

, and from Equation (32), we can imply that:

In Equation (40),

is estimated by using ANFIS. The recursive least square (RLS) method parameter estimation algorithm is shown in the following equations:

where

and

is the identity matrix.

ANFIS has the capabilities of rapid modeling and infinite approximation. The selected training input parameter is

and the output parameter is

. Each input defines two Gaussian membership functions. This configuration generates a comprehensive fuzzy rule base consisting of 64 rules. The consequence part of each rule is a linear first-order function of the input. This structure is implemented in a five-layer adaptive network, which contains a total of 12 premise parameters and 448 consequence parameters. These parameters are optimized online using the recursive least squares method to minimize the compensation error. The control law after compensation is shown as:

where

,

is the number of fuzzy rules, and

is the consequent function of the

i-th rule.

3.3. Exoskeleton Linkage Mechanism Switching Control

This paper investigates the switching control strategy for the exoskeleton linkage mechanism, aiming to achieve smooth transitions and coordination between different phases of the exoskeleton’s movement. Through the switching control strategy, the system can effectively manage dynamic changes during the movement, such as the transition between the support phase and the swing phase. The goal of the strategy is to optimize the overall performance and responsiveness of the exoskeleton, ensuring that the motion trajectories and dynamic performance of both legs remain symmetrical throughout the gait cycle, even when the legs are in different phases (for example, one leg in the support phase and the other in the swing phase). The switching algorithm ensures smooth and coordinated transitions between these two phases.

Switching Rule

Switching refers to the control switching of one leg of the exoskeleton from the support phase to the swing phase and then back to the support phase. Due to the different dynamic equations of the support phase and the swing phase, as well as the different controllers, direct switching will cause torque variation and impact. A smooth transition switch is, therefore, required.

By using the foot pressure sensor, the pressure of the exoskeleton in contact with the ground can be measured, and each pressure data point is recorded. The torque during the switching process is governed by the following equations:

where

,

, and

are the pressure values measured on the sole of the foot, left foot, and right foot, respectively,

is the swing phase pressure threshold, and

is the pressure threshold of the support phase.

The switching parameters

and

are adaptively obtained, with the aim of making the switching process from the support phase and without torque variation. Therefore, we use a switching rule:

where

is a first-order linear combination of error and error rate that measures whether the error is decaying at the desired exponential rate.

represents the distance between the current position and the target position and

is its derivative.

By defining a Lyapunov candidate:

then its derivative can be obtained as:

To ensure stability, the auxiliary variable is designed as a linear combination of the tracking error and its derivative, , where is a tuning constant.

Substituting

into Equation (51) yields:

Therefore, when , it follows that , indicating that the switching error converges asymptotically to zero and the transition between the support and swing phases is smooth and stable.

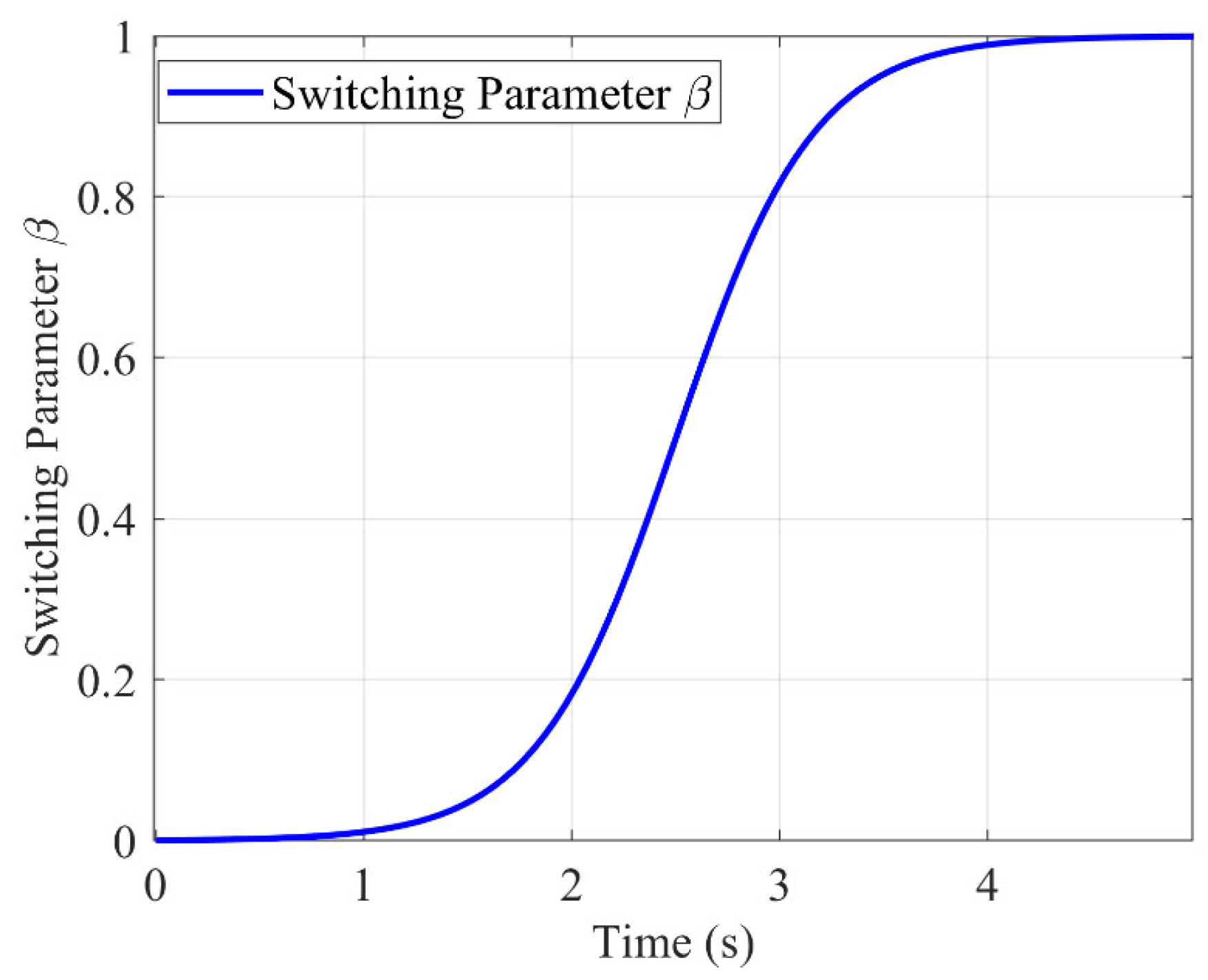

The switching parameter

can be defined as:

where

,

, and

h are magnification factors to amplify

. To ensure the smoothness of the handover, let

and

to achieve the transformation of

from 0 to 1. Meanwhile, when

takes 0 or 1, the changes are stable, and a smooth transition can be achieved. The generated

trajectory diagram is shown in

Figure 5.

Equation (53) provides a concrete S-shaped function that implements the abstract monotonic mapping defined in Equation (47).

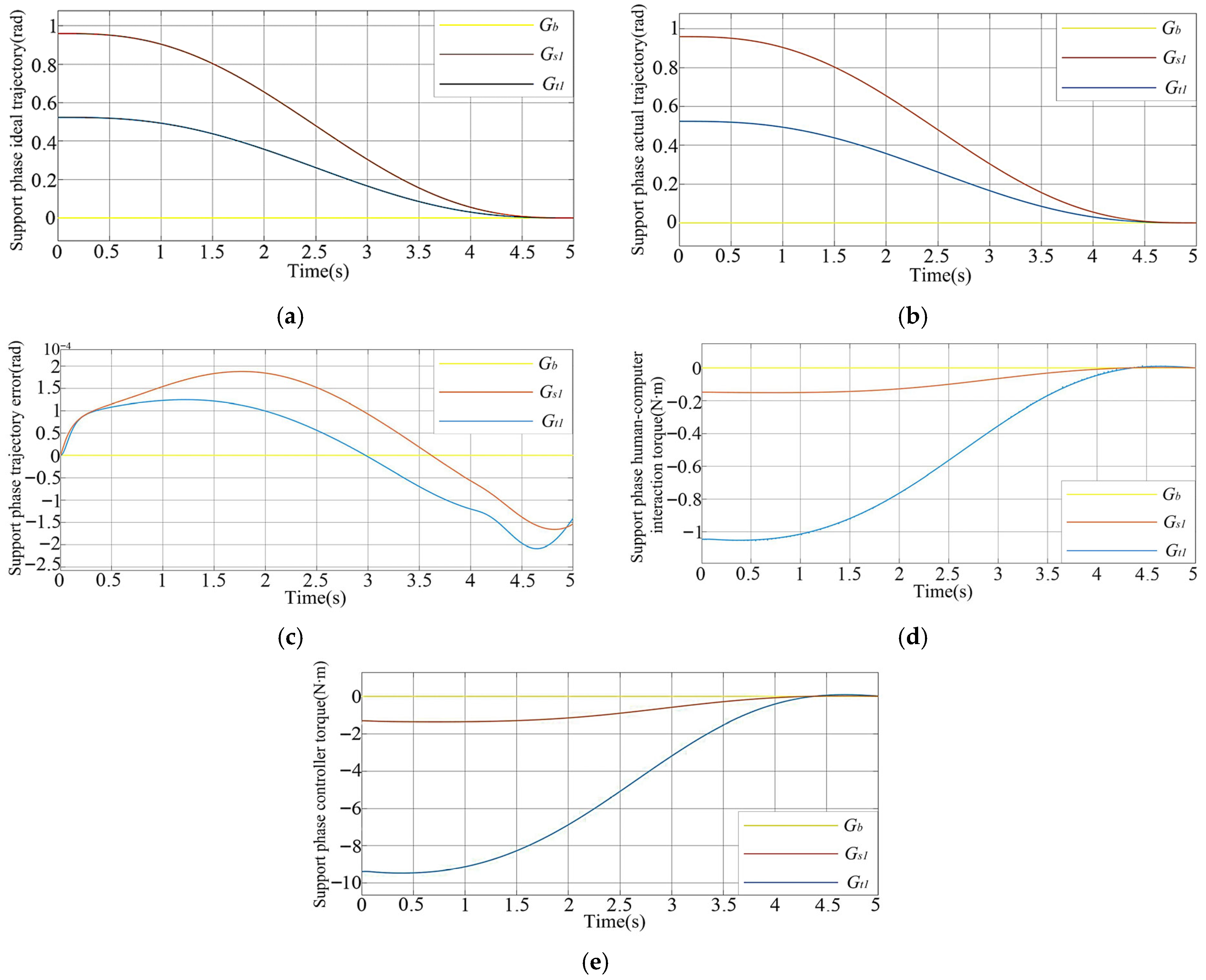

5. Conclusions

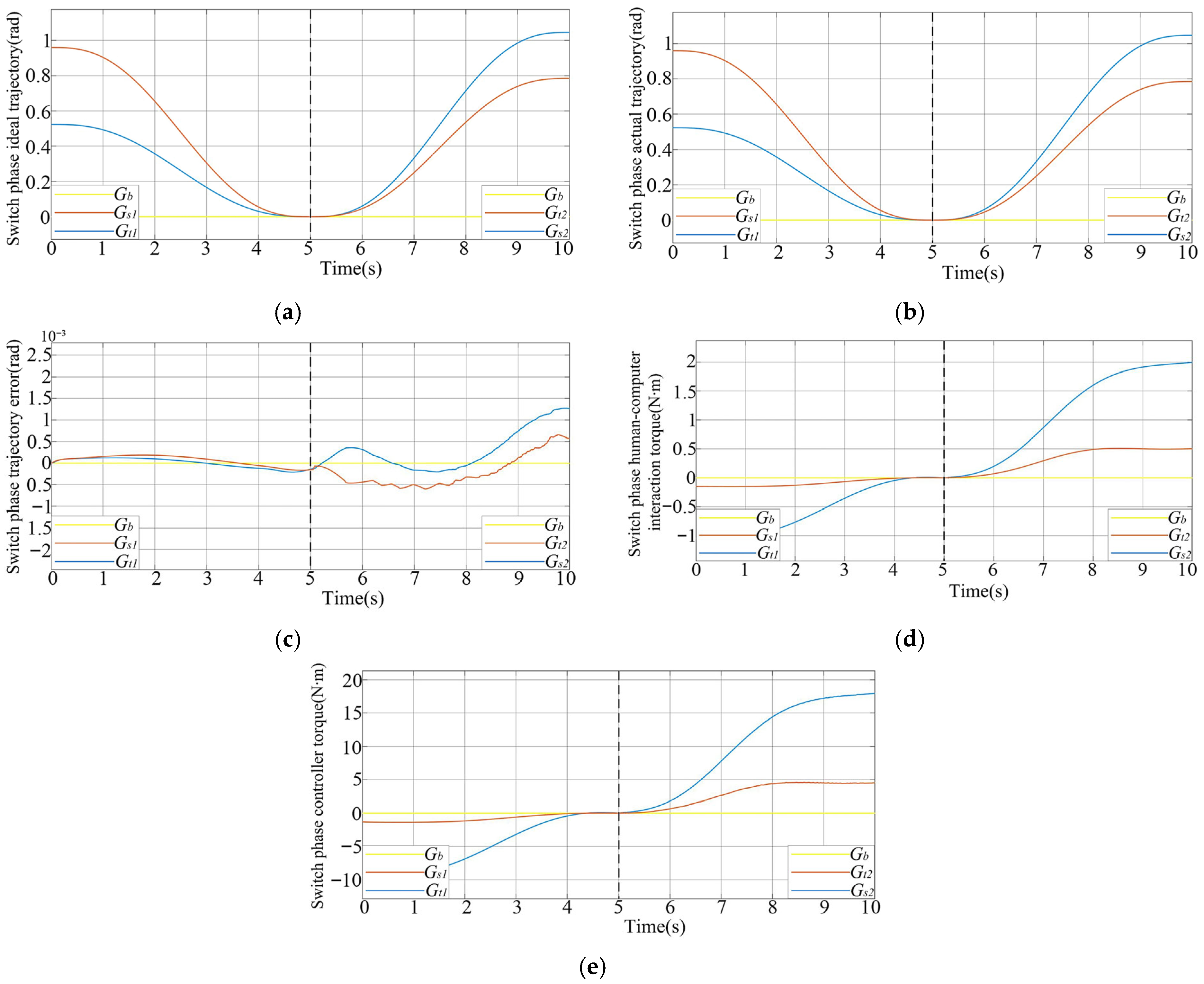

This study proposed an innovative intelligent switching control strategy for a five-link exoskeleton robot. During the support phase, the TSMC technology was employed to ensure stability. In the swing phase, a hybrid PID-ANFIS controller was used to achieve precise and compliant movements. During the switching phase, the intelligent control algorithm ensured a smooth transition. During all gait phases, the trajectory tracking error was controlled within 0.05. The system achieved a stable torque amplification ratio from 1:6 to 1:10, significantly reducing the physical effort required by the user.

The limitations of this study lie in its verification method being based solely on simulation, which cannot fully capture the complex dynamics of real human–machine interaction. The proposed control performance has been evaluated only under preset walking conditions without involving actual hardware or human participants. Future work will focus on implementing the control framework on a physical exoskeleton prototype to validate its real-world performance, robustness, and comfort. In addition, the incorporation of physiological signals or adaptive learning mechanisms will be explored to further enhance adaptability and safety during human–robot interaction.

Based on the findings, it is recommended that future studies apply the proposed intelligent switching control to various exoskeleton platforms and rehabilitation tasks to evaluate its generalization capability. Integrating EMG-based intent detection, user comfort assessment, and safety monitoring into the control framework is also encouraged. Furthermore, collaboration between control engineers and clinical researchers is essential to promote the practical deployment of intelligent exoskeletons in rehabilitation environments.