Error-Driven Varying-Gain in Zeroing Neural Networks for Solving Time-Varying Quadratic Programming Problems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- An error-driven varying-gain scheme is proposed for the ZNN model. The initial gain is large due to the large initial residual error, which facilitates the rapid reduction of the large initial residual error.

- (ii)

- Rigorous theoretical analysis, along with detailed proofs, is presented for the varying gain zeroing neural network (VGZNN) model. These analyses demonstrate that the VGZNN model achieves superior convergence performance when integrated with the proposed error-driven varying-gain scheme.

- (iii)

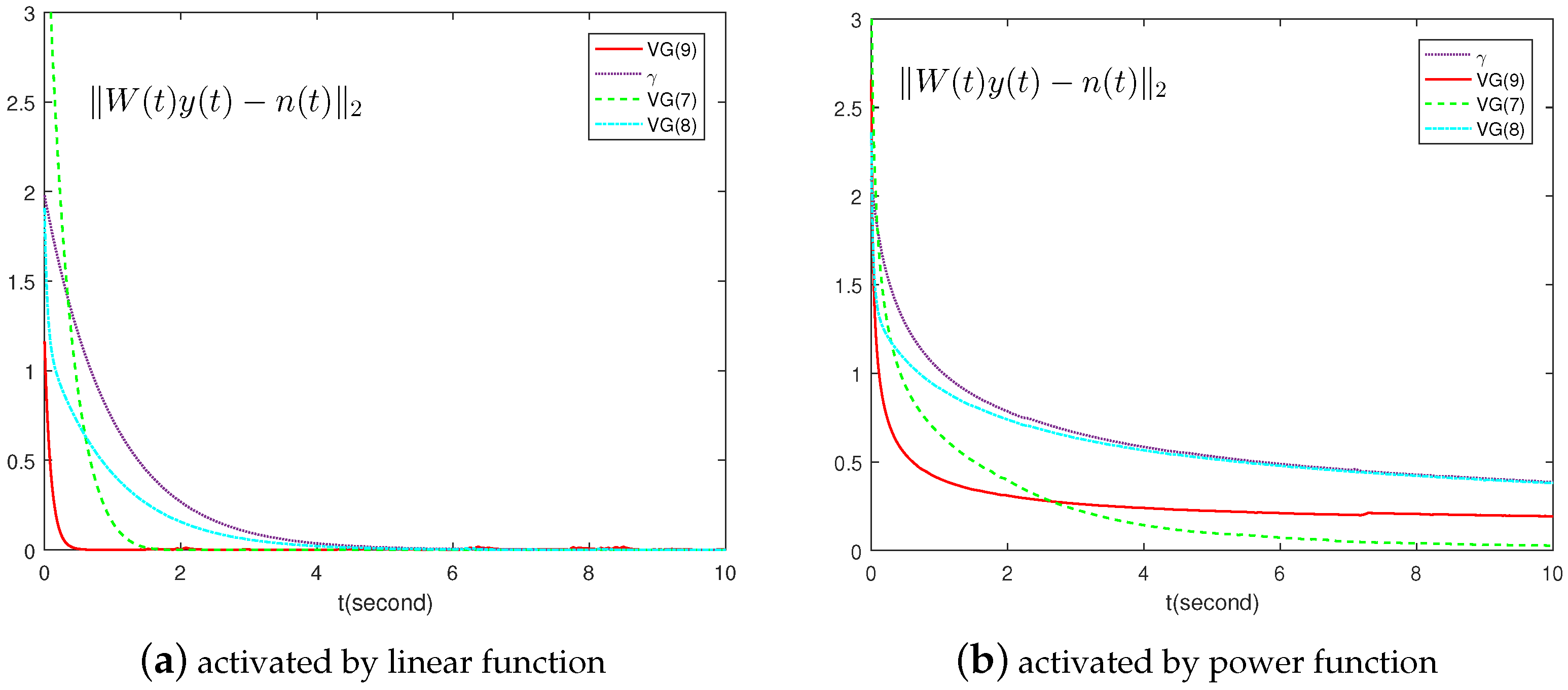

- In the experimental section, a numerical TVQP example is simulated, analyzed, and compared with existing methods. These results further validate that the proposed error-driven varying-gain scheme outperforms the other three varying-gain schemes, making it the optimal choice.

2. Varying Gain for Solving TVQP Problems

- (1)

- the linear activation function: ;

- (2)

- the power function: with ;

- (3)

- and the sign-bi-power activation function:with denoting the following signum function:

3. Theoretical Analysis

4. Illustrative Examples

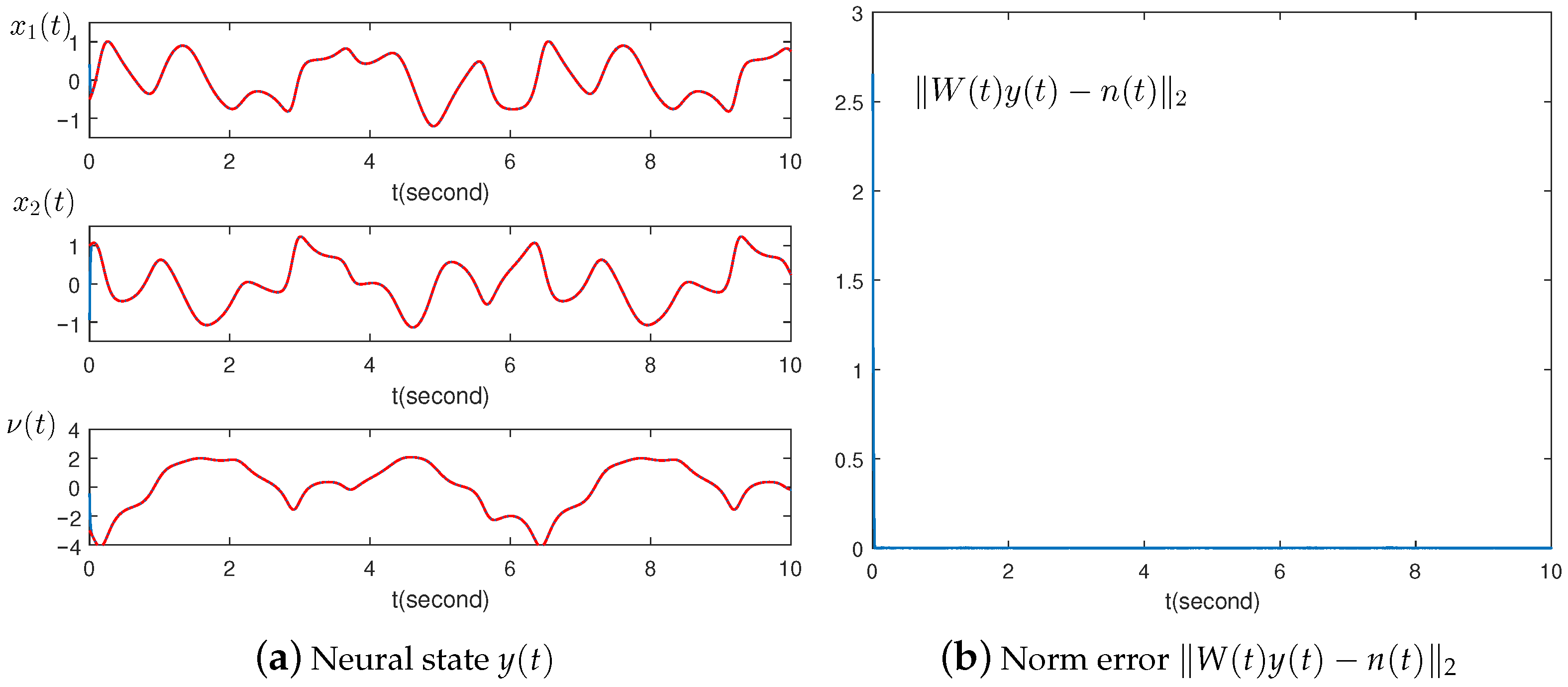

4.1. Example 1: Numerical Example

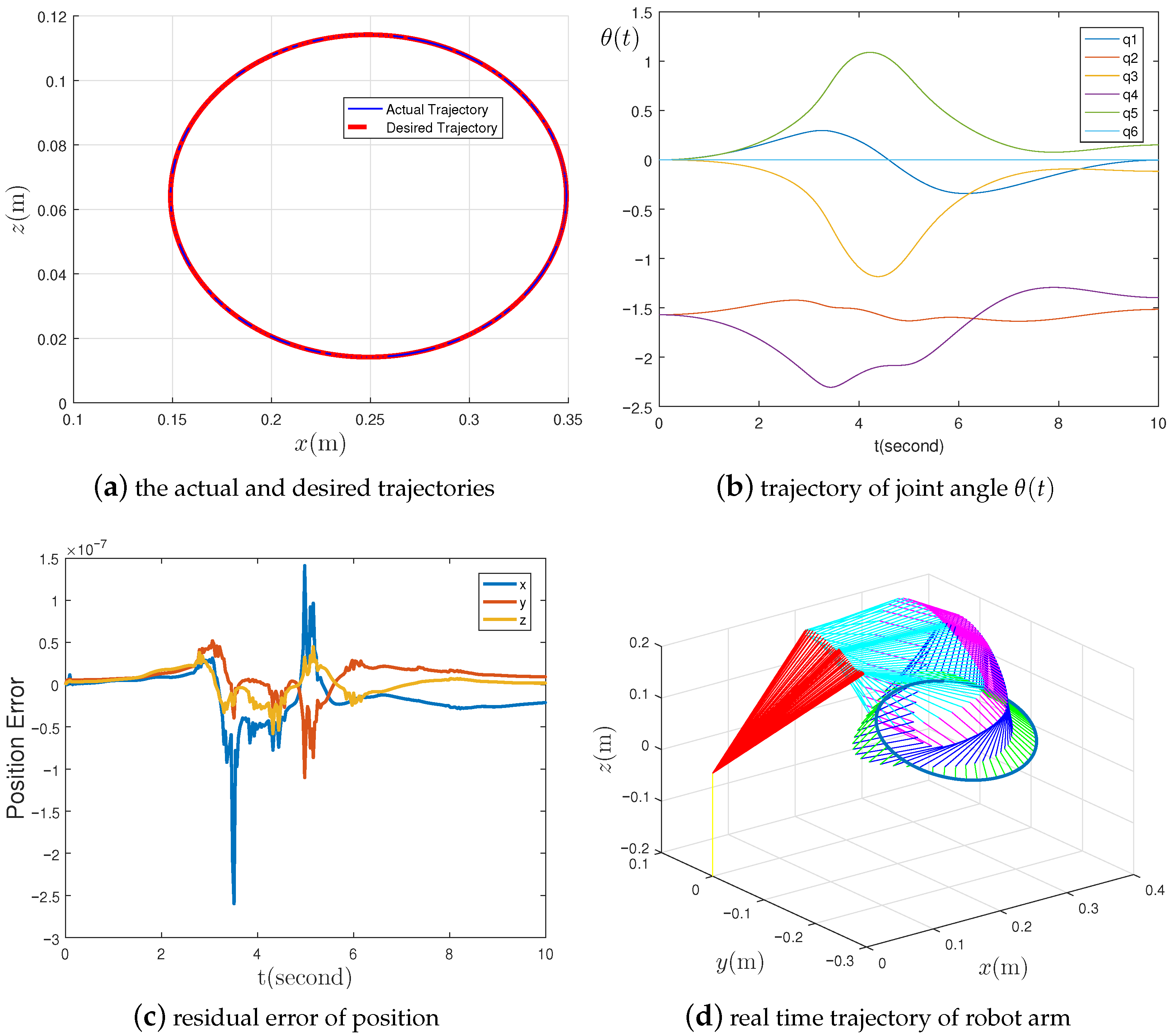

4.2. Example 2: TVQP Problem Solution for a Robot Manipulator

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, J.; Yi, C. An adaptive gradient-descent-based neural networks for the on-line solution of linear time variant equations and its applications. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Tang, S.; Jin, L.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J. Nonconvex activation noise-suppressing neural network for time-varying quadratic programming: Application to omnidirectional mobile manipulator. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 10786–10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, T.V.; Anh, P.N.; Truong, N.D. Convergence of the projection and contraction methods for solving bilevel variational inequality problems. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 10867–10885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yang, Z.; Ye, J. Kernel-Free Nonlinear Support Vector Machines for Multiview Binary Classification Problems. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 2023, 6259041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Yin, J.; Bai, C. An effective global optimization algorithm for quadratic programs with quadratic constraints. Symmetry 2019, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Pu, Z.; Ma, M. An efficient vehicle-following predictive energy management strategy for PHEV based on improved sequential quadratic programming algorithm. Energy 2021, 219, 119595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, H.; Jin, L. A lower dimension zeroing neural network for time-variant quadratic programming applied to robot pose control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 11835–11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zuo, Q.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y. A Predefined-Time Robust Sliding Mode Control Based on Zeroing Neural Dynamics for Position and Attitude Tracking of Quadrotor. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 2438–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Chen, J.; Li, L. A Direct Discrete Recurrent Neural Network with Integral Noise Tolerance and Fuzzy Integral Parameters for Discrete Time-Varying Matrix Problem Solving. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tian, X. Numerical solution method for general interval quadratic programming. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 202, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Duan, X.; Huang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z. Neural Networks With Linear Adaptive Batch Normalization and Swarm Intelligence Calibration for Real-Time Gaze Estimation on Smartphones. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024, 2024, 2644725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorokhovatskyi, V.; Tvoroshenko, I.; Yakovleva, O.; Hudáková, M.; Gorokhovatskyi, O. Application a committee of Kohonen neural networks to training of image classifier based on description of descriptors set. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 73376–73385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Okuyama, Y.; Tomioka, Y.; Shin, J. Spatial–temporal attention with graph and general neural network-based sign language recognition. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2024, 27, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yi, C. Zhang Neural Networks and Neural-Dynamic Method; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Gong, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H. A Discrete Sliding-Mode Reaching-Law Zeroing Neural Solution for Dynamic Constrained Quadratic Programming. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4724–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, N.M.; Thuseethan, S.; Azid, S.I.; Azam, S. An Innovative Coverage Path Planning Approach for UAVs to Boost Precision Agriculture and Rescue Operations. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2025, 4700518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, S. A new visual-inertial odometry scheme for unmanned systems in unified framework of zeroing neural networks. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 129017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Han, L.; Cao, X.; Li, S.; Li, J. Double integral-enhanced Zeroing neural network with linear noise rejection for time-varying matrix inverse. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2024, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhang, C.; Cang, N.; Jia, Z.; Xue, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Wang, Y. Harmonic noise rejection zeroing neural network for time-dependent equality-constrained quadratic program and its application to robot arms. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 21, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, S.; Yi, C. A super-twisting algorithm combined zeroing neural network with noise tolerance and finite-time convergence for solving time-variant Sylvester equation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 248, 123380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Lei, X.; Chen, C.; Li, Z. A fuzzy activation function based zeroing neural network for dynamic Arnold map image cryptography. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 230, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Ning, Y.; Xiao, L.; Luo, J.; Li, X. Finite-time zeroing neural networks with novel activation function and variable parameter for solving time-varying Lyapunov tensor equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2023, 452, 128072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, Z.; Ke, Y.; Stanimirović, P.S. New activation functions and Zhangians in zeroing neural network and applications to time-varying matrix pseudoinversion. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 225, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Xu, J.; Zheng, B. A Novel Robust and Predefined-Time Zeroing Neural Network Solver for Time-Varying Linear Matrix Equation. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2025, 48, 6048–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Tao, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; He, Y. A parameter-changing and complex-valued zeroing neural-network for finding solution of time-varying complex linear matrix equations in finite time. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 6634–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cai, H.; Xiao, L.; He, Y.; Li, L.; Zuo, Q.; Li, J. A predefined-time adaptive zeroing neural network for solving time-varying linear equations and its application to UR5 robot. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 4703–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Han, Q.L.; Ge, X.; Sanjayan, J. A zeroing neural network-based approach to parameter-varying platooning control of connected automated vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Yi, C. Time-varying learning rate for recurrent neural networks to solve linear equations. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, G.; Liu, Z. Recurrent neural network with scheduled varying gain for solving time-varying QP. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 71, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerontitis, D.; Behera, R.; Tzekis, P.; Stanimirović, P. A family of varying-parameter finite-time zeroing neural networks for solving time-varying Sylvester equation and its application. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 403, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikis, V.N.; Stanimirović, P.S.; Mourtas, S.D.; Xiao, L.; Karabašević, D.; Stanujkić, D. Zeroing neural network with fuzzy parameter for computing pseudoinverse of arbitrary matrix. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 30, 3426–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciano, T.; Ferrara, M. Karush-kuhn-tucker conditions and lagrangian approach for improving machine learning techniques: A survey and new developments. Atti Accad. Peloritana -Pericolanti-Cl. Sci. Fis. Mat. Nat. 2024, 102, 1. [Google Scholar]

| Time (s) | Residual Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 10 | ||

| 10 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 10 |

| Gain Scheme | Activation Function | Time (s) | Residual Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| linear function | |||

| power function | 10 | ||

| (7) with | linear function | ||

| power function | 10 | ||

| (8) with , and | linear function | ||

| power function | 10 | ||

| (9) with , | linear function | ||

| power function | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Zhong, J.; Li, J.; Sun, C. Error-Driven Varying-Gain in Zeroing Neural Networks for Solving Time-Varying Quadratic Programming Problems. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111825

Chen Y, Zhong J, Li J, Sun C. Error-Driven Varying-Gain in Zeroing Neural Networks for Solving Time-Varying Quadratic Programming Problems. Symmetry. 2025; 17(11):1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111825

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yuhuan, Junliu Zhong, Jiawei Li, and Chengli Sun. 2025. "Error-Driven Varying-Gain in Zeroing Neural Networks for Solving Time-Varying Quadratic Programming Problems" Symmetry 17, no. 11: 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111825

APA StyleChen, Y., Zhong, J., Li, J., & Sun, C. (2025). Error-Driven Varying-Gain in Zeroing Neural Networks for Solving Time-Varying Quadratic Programming Problems. Symmetry, 17(11), 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17111825