Insulator Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLO11s in Snowy Weather Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

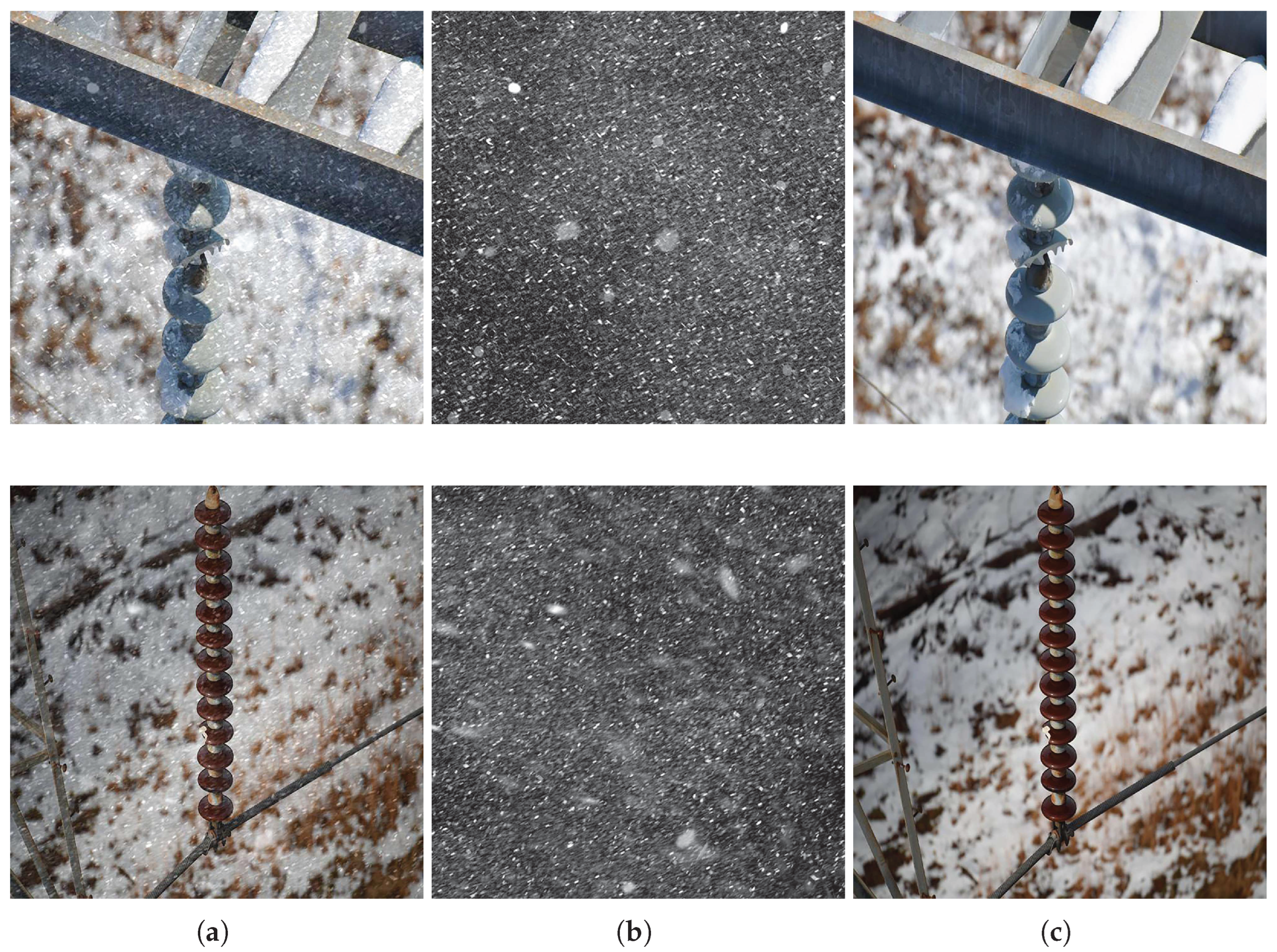

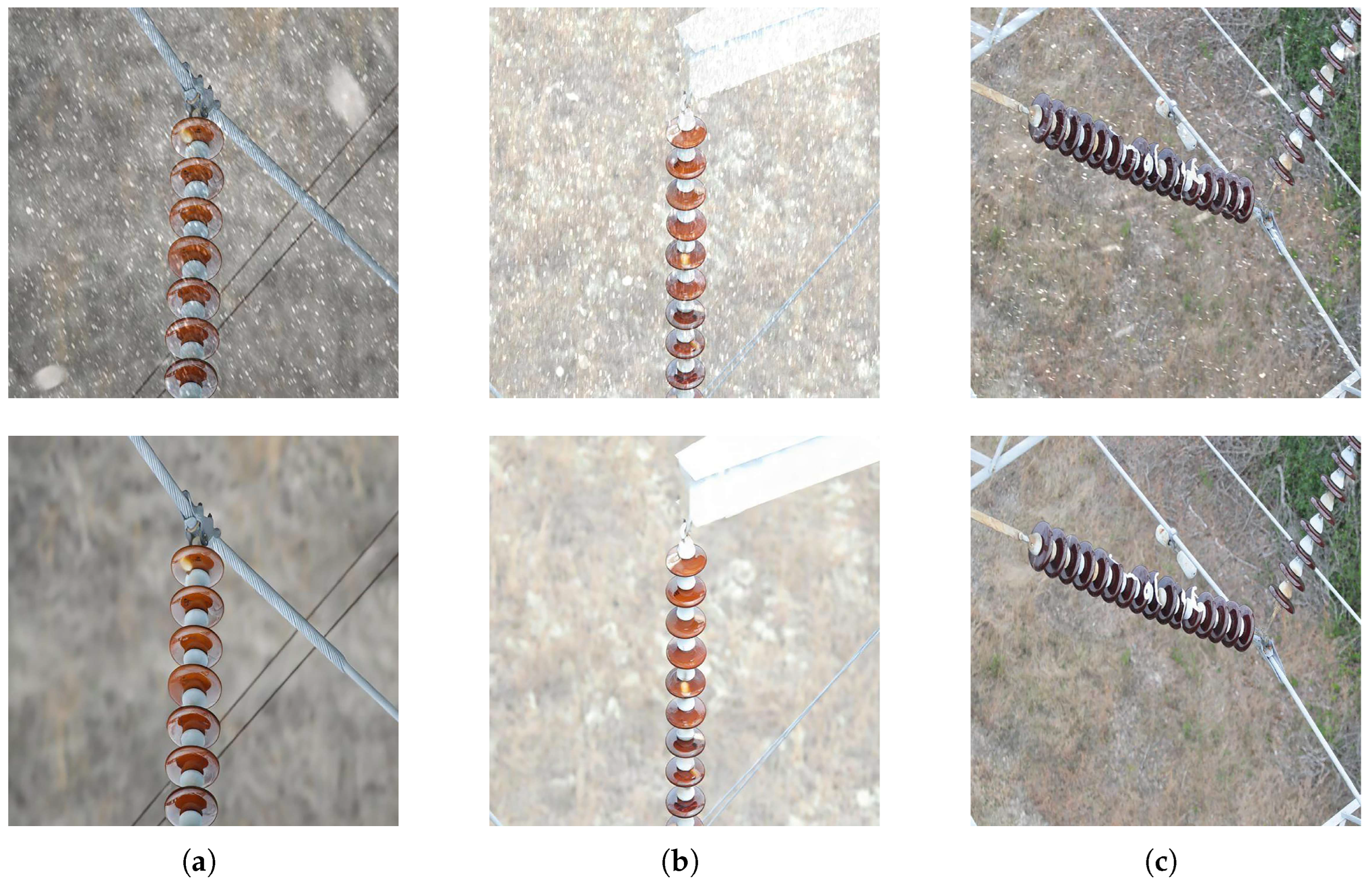

- High-quality insulator images captured by UAVs were curated to establish the Insulator1600 dataset. To simulate severe weather conditions, synthetic snow artifacts were algorithmically introduced, generating the InsulatorSnow1600 dataset. Three state-of-the-art desnowing models were evaluated using SSIM and PSNR metrics, with FocalNet selected for its superior capability to restore image clarity and preserve structural details. The processed outputs formed the final InsulatorDeSnow1600 dataset.

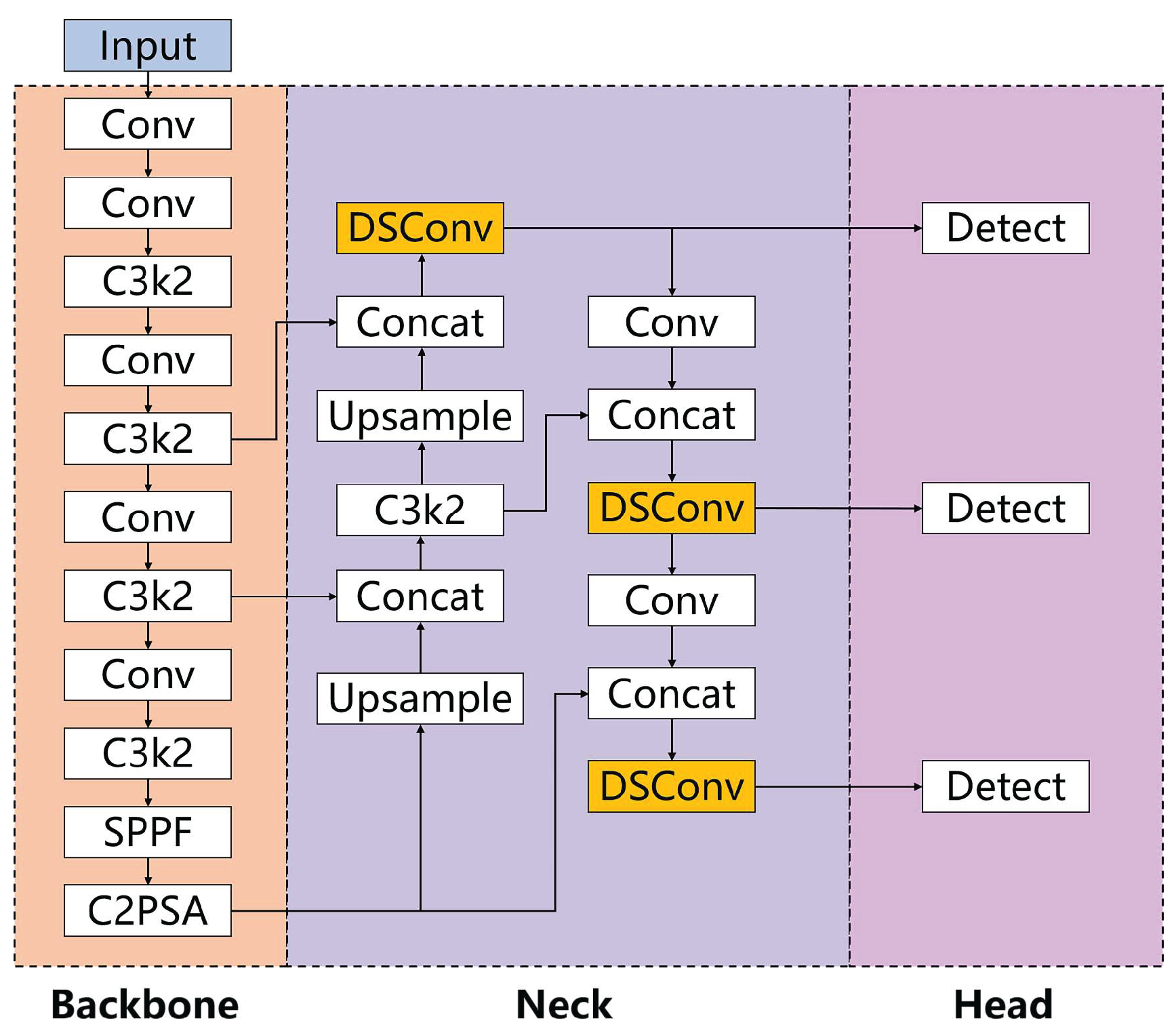

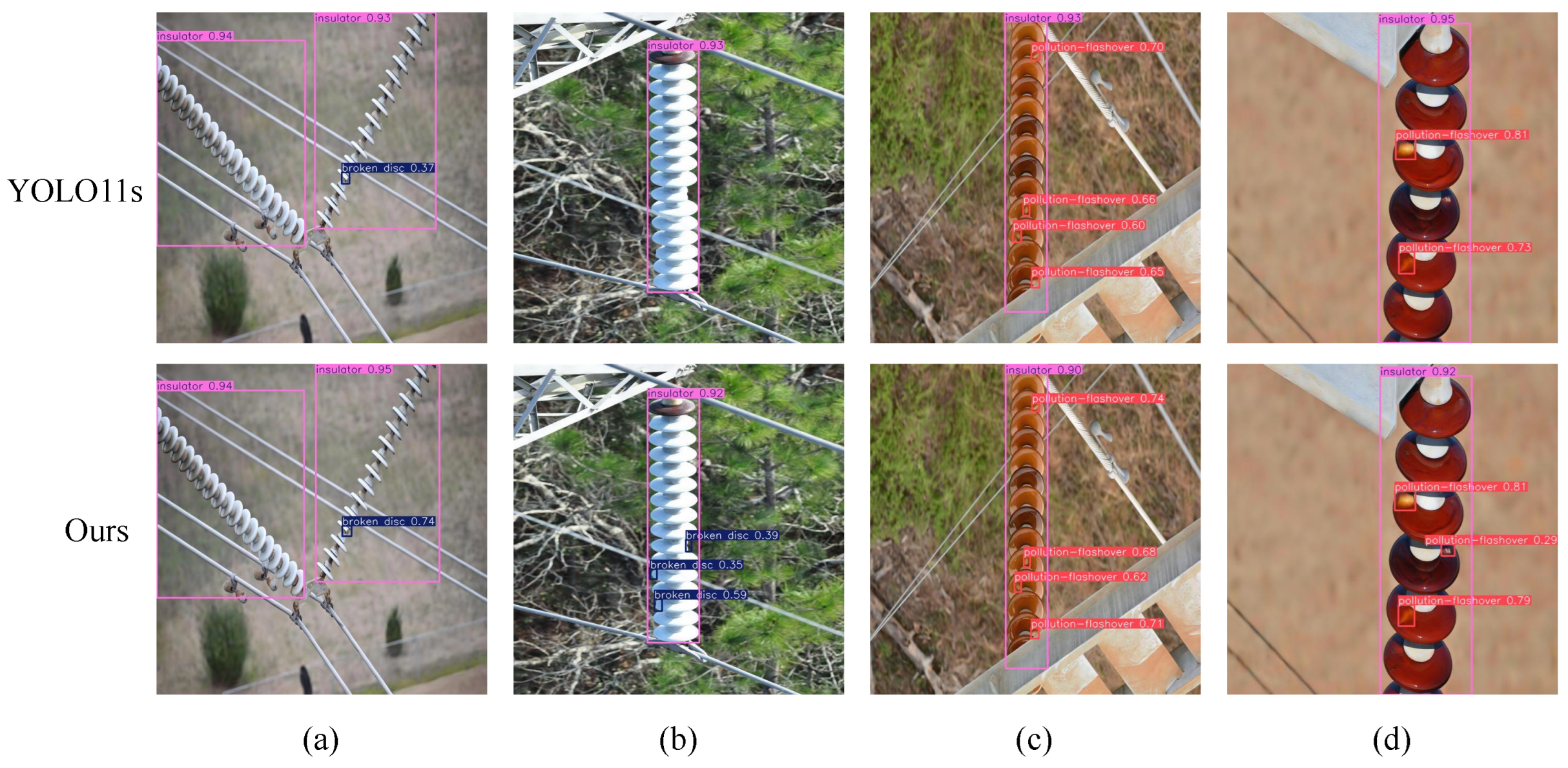

- The proposed framework enhances the YOLO11s baseline through two key innovations: First, a Dynamic Snake Convolution module was integrated to improve feature extraction for tubular structures inherent to insulators. Second, the MPDIoU loss function was incorporated to optimize bounding box regression, effectively balancing localization accuracy and recall performance.

- Ablation studies and comparative experiments demonstrate that the enhanced YOLO11s model surpasses its baseline counterpart across all evaluation metrics. The proposed solution outperforms mainstream YOLO variants (v5s, v6s, v7-tiny, v8s, v9s, v10s, and v10m) while also achieving superior detection accuracy versus established models including Faster R-CNN, SSD, TOOD, and Deformable DETR.

2. Datasets and Desnowing Models

2.1. Insulator Dataset Under Snowy Conditions

2.2. FocalNet Desnowing Network

3. YOLO11 Algorithm Model Structure and Improvements

3.1. The Model Structure of YOLO11

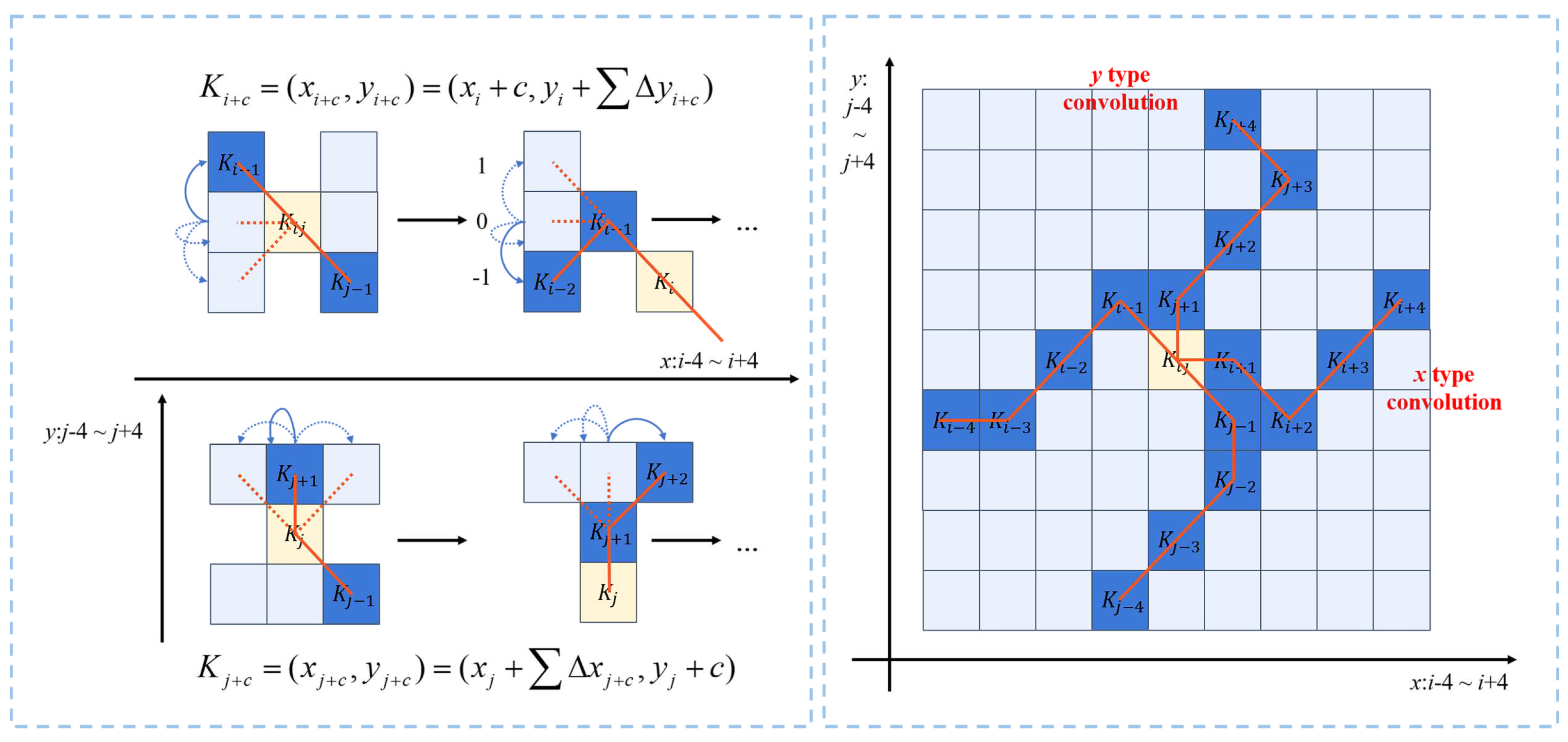

3.2. Dynamic Snake Convolution

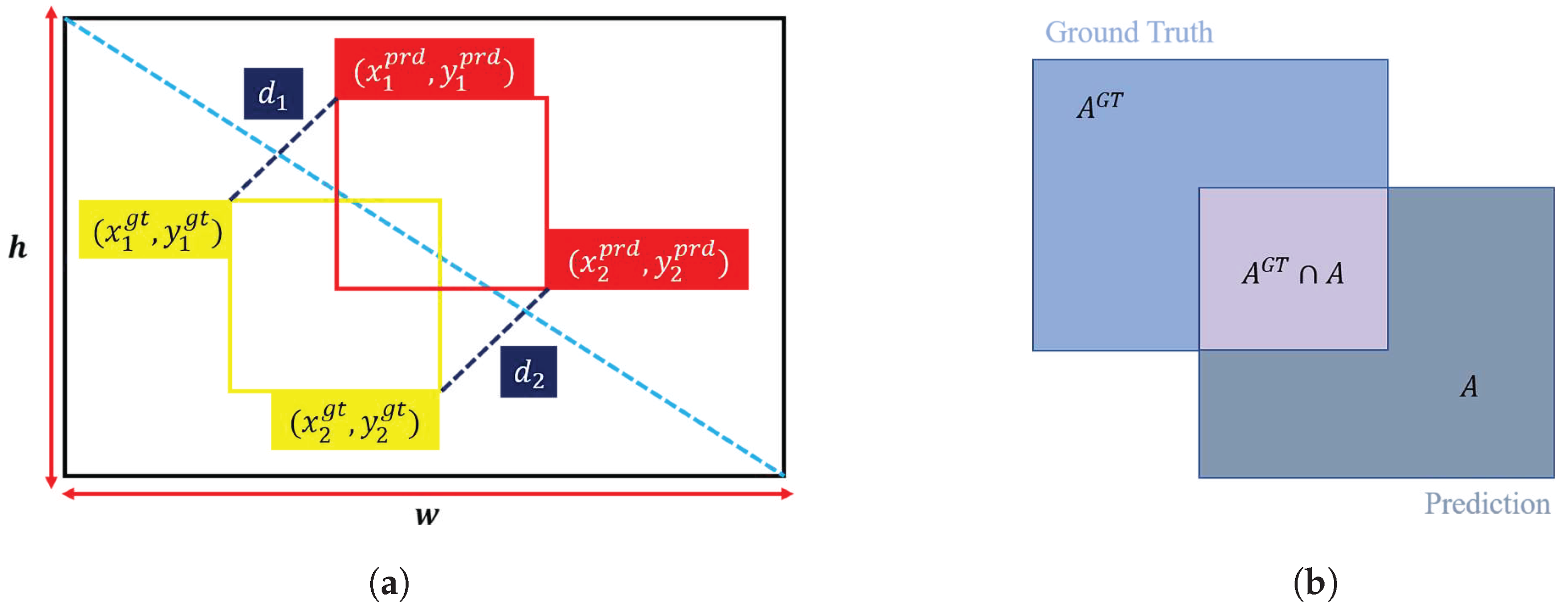

3.3. MPDIoU Loss Function

4. Simulation Experiments and Result Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment Configuration

4.2. Evaluation Metrics of the Experiment

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.4. Comparative Experiment

4.5. Visualization of Detection Results

4.6. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Song, Y. LiteYOLO-ID: A lightweight object detection network for insulator defect detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Li, Z. An insulator location and defect detection method based on improved yolov8. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 106781–106792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Sun, H. Defect Detection of Insulator Based on YOLO Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Electronic Technology and Information Science (ICETIS), Hangzhou, China, 17–19 May 2024; pp. 232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liao, Z.; Xu, M. Wire insulator fault and foreign body detection algorithm based on YOLO v5 and YOLO v7. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Electrical, Automation and Computer Engineering (ICEACE), Changchun, China, 26–28 December 2023; pp. 1412–1417. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Qin, L.; Deng, X.; Liu, K. MFI-YOLO: Multi-fault insulator detection based on an improved YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 39, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Lv, G.; Chen, J. A2MADA-YOLO: Attention Alignment Multiscale Adversarial Domain Adaptation YOLO for Insulator Defect Detection in Generalized Foggy Scenario. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5011419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Feng, L.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q. MCI-GLA plug-in suitable for YOLO series models for transmission line insulator defect detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 9002912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Jaw, D.W.; Huang, S.C.; Hwang, J.N. Desnownet: Context-aware deep network for snow removal. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3064–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.T.; Fang, H.Y.; Hsieh, C.L.; Tsai, C.C.; Chen, I.; Ding, J.J.; Kuo, S.Y. All snow removed: Single image desnowing algorithm using hierarchical dual-tree complex wavelet representation and contradict channel loss. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 4196–4205. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, T. Snow mask guided adaptive residual network for image snow removal. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2023, 236, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, R.; Yu, Y.; Luo, W.; Li, C. Deep dense multi-scale network for snow removal using semantic and depth priors. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 7419–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.T.; Fang, H.Y.; Ding, J.J.; Tsai, C.C.; Kuo, S.Y. JSTASR: Joint size and transparency-aware snow removal algorithm based on modified partial convolution and veiling effect removal. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 754–770. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Y.; Tan, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ji, H. Image desnowing via deep invertible separation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 3133–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fu, X.; Zha, Z.J. Exploring Local Sparse Structure Prior for Image Deraining and Desnowing. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 32, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, N.; Lin, J.; Lin, J.; Zhao, T. Desnowformer: An effective transformer-based image desnowing network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), Suzhou, China, 13–16 December 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Ren, W.; Cao, X.; Knoll, A. Focal network for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 13001–13011. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; He, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 6070–6079. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Xu, Y. Mpdiou: A loss for efficient and accurate bounding box regression. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.07662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Gao, D. Deep learning based insulator fault detection algorithm for power transmission lines. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.T.; Huang, Z.K.; Tsai, C.C.; Yang, H.H.; Ding, J.J.; Kuo, S.Y. Learning multiple adverse weather removal via two-stage knowledge learning and multi-contrastive regularization: Toward a unified model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17653–17662. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. Tood: Task-aligned one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 3490–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

| Laboratory Setting | Configuration Information |

|---|---|

| Running system | Ubuntu 20.04 |

| CPU | 14 vCPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8362 CPU @ 2.80 GHz |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 (24 GB) |

| Deep learning framework | Pytorch 1.10.1 |

| Programming language | Python 3.9.20 |

| Cuda | 11.3 |

| Image size | 640 × 640 |

| Training epoch | 1000 |

| Learning rate | 0.0001 |

| Weight decay | 0.0005 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Classes | 7 |

| Type | Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Desnowing | SMGARN [13] | 23.11 | 0.86 |

| Chen et al. [23] | 25.65 | 0.83 | |

| FocalNet [19] | 33.77 | 0.93 |

| Method | Models | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desnowing | Detection | |||||

| Faster-RCNN [2] | FocalNet | Faster-RCNN | 87.4 | 74.9 | 80.3 | 52.7 |

| SSD [24] | FocalNet | SSD | 89.5 | 77.7 | 81.2 | 52.3 |

| Tood [25] | FocalNet | Tood | 90.9 | 81.0 | 86.1 | 59.3 |

| Deformable DETR [26] | FocalNet | Deformable DETR | 89.1 | 81.3 | 84.3 | 55.3 |

| YOLOv5s | FocalNet | YOLOv5s | 90.2 | 82.7 | 84.5 | 54.3 |

| YOLOv6s | FocalNet | YOLOv6s | 92.1 | 79.5 | 84.3 | 57.6 |

| YOLOv7-tiny | FocalNet | YOLOv7-tiny | 92.6 | 83.8 | 86.8 | 56.1 |

| YOLOv8s | FocalNet | YOLOv8s | 92.0 | 82.9 | 85.7 | 57.1 |

| YOLOv9s | FocalNet | YOLOv9s | 92.0 | 83.3 | 86.4 | 58.9 |

| YOLOv10s | FocalNet | YOLOv10s | 87.5 | 77.4 | 82.5 | 55.2 |

| YOLOv10m | FocalNet | YOLOv10m | 82.2 | 79.5 | 82.6 | 55.6 |

| YOLO11s | / | YOLO11s | 88.5 | 74.3 | 77.8 | 50.4 |

| YOLO11s | FocalNet | YOLO11s | 92.6 | 81.1 | 85.3 | 57.1 |

| YOLO11s | SMGARN | YOLO11s | 92.1 | 80.1 | 85.6 | 56.6 |

| YOLO11s | Chen et al. | YOLO11s | 91.7 | 81.1 | 86.1 | 57.6 |

| YOLOv12s | FocalNet | YOLOv12s | 89.8 | 79.7 | 85.7 | 56.1 |

| Ours | FocalNet | YOLO11s | 93.5 | 85.0 | 88.6 | 60.1 |

| Model | MPDIoU | DSConv | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 19 | 22 | ||||||

| A | √ | 88.9 | 84.0 | 86.2 | 58.4 | |||

| B | √ | √ | 89.7 | 84.8 | 86.8 | 58.4 | ||

| √ | √ | 88.5 | 84.4 | 86.4 | 57.7 | |||

| √ | √ | 91.6 | 83.0 | 87.0 | 58.3 | |||

| C | √ | √ | √ | 90.9 | 86.0 | 87.2 | 57.4 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 91.3 | 84.6 | 88.0 | 58.5 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 90.4 | 85.3 | 87.3 | 58.2 | ||

| D | √ | √ | √ | √ | 93.5 | 85.0 | 88.6 | 60.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, Z.; Deng, S.; Liu, Q. Insulator Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLO11s in Snowy Weather Environment. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101763

Ding Z, Deng S, Liu Q. Insulator Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLO11s in Snowy Weather Environment. Symmetry. 2025; 17(10):1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101763

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Ziwei, Song Deng, and Qingsheng Liu. 2025. "Insulator Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLO11s in Snowy Weather Environment" Symmetry 17, no. 10: 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101763

APA StyleDing, Z., Deng, S., & Liu, Q. (2025). Insulator Defect Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLO11s in Snowy Weather Environment. Symmetry, 17(10), 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17101763