Abstract

We propose a new asymmetric discrete model by combining the uniform and Poisson–Ailamujia distributions using the binomial decay transformation method. The distribution, named the uniform Poisson–Ailamujia, due to its flexibility is a good alternative to the well-known Poisson and geometric distributions for real data applications in public health, biology, sociology, medicine, and agriculture. Its main statistical properties are studied, including the cumulative and hazard rate functions, moments, and entropy. The new distribution is considered to be suitable for modeling purposes; its parameter is estimated by eight classical methods. Three applications to biological data are presented herein.

1. Introduction

Discrete distributions are quite useful for modeling discrete lifetime data in many situations. Recently, several continuous distributions have been discretized for modeling lifetime data, such as those summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Some discretized continuous distributions.

On the other hand, a natural discrete analog of the continuous Lindley model, called natural discrete Lindley (NDL), was introduced by [8] as a mixture of the negative binomial and geometric distributions. Several reliability properties of the NDL were explored by [9].

Let N and X be two discrete random variables denoting the numbers of particles entering and leaving an attenuator, with their probability mass functions (pmfs) and that are connected by the binomial decay transformation introduced by Hu et al. [10]

where is the attenuating coefficient. Hu et al. [10] defined as a pmf of a Poisson distribution with rate parameter and illustrated that is also a Poisson distribution with rate . They investigated the quantitative relation between the input and output distributions after the attenuation. In recent studies, new discrete models have been constructed by compounding two discrete distributions. For example, Déniz [11] defined the uniform Poisson, Akdoğan et al. [12] proposed the uniform geometric, and Kuş et al. [13] introduced the binomial discrete Lindley.

In this paper, we introduce the asymmetric uniform Poisson–Ailamujia (UPA) distribution using the methodology of Hu et al. [10]. This distribution is a competitor to the Poisson–Ailamujia (PA) model, and it is suitable for fitting datasets with excesses of ones. We estimate the parameter of the UPA distribution using eight classical methods and provide detailed simulations to explore the behavior of the estimators.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines the new one-parameter distribution and some of its properties. Two actuarial measures are calculated in Section 3. The estimation methods are discussed in Section 4. In Section 5, the efficiency of the estimators is studied via Monte Carlo simulations. Section 6 provides three real applications of the new distribution. Section 7 offers some conclusions.

2. The Discrete UPA Distribution

The PA distribution was derived from the Poisson compounding scheme based on the continuous Ailamujia distribution by Lv et al. [14]. It was pioneered by Hassan et al. [15] for modeling count data, offering a new alternative to the Poisson and the negative binomial, among other models. Its pmf has the form (for ).

Equation (2) can be expressed as

where has the binomial model. Now, let have the discrete uniform U with parameter , and let N have a PA distribution with parameter . Then, the pmf of the UPA random variable (), say, UPA, is as follows (for ):

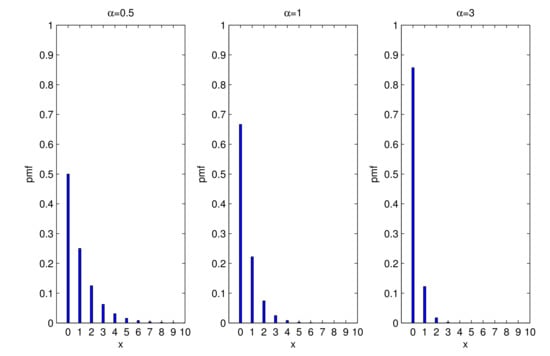

Figure 1 displays plots of the pmf of X, which is unimodal. The probabilities of decrease when x increases.

Figure 1.

Pmf of the UPA distribution for some values of .

2.1. Properties

The survival function (sf) of the UPA distribution is as follows (for ):

The cumulative distribution function (cdf) of X reduces to

The hazard rate function (hrf) of X can be defined as , where . Then, the hrf of the UPA distribution follows from Equations (4) and (5) as

The moment generating function of X is

The first fourth ordinary moments of X are

The variance, skewness, and kurtosis of X are obtained from these expressions as

We note that the new distribution is over-dispersed since the index of dispersion (ID)

Hence, the UPA distribution can be used for modeling over-dispersed data. In addition, it is right-skewed and leptokurtic, since and , respectively. The UPA distribution is a heavy-tailed distribution.

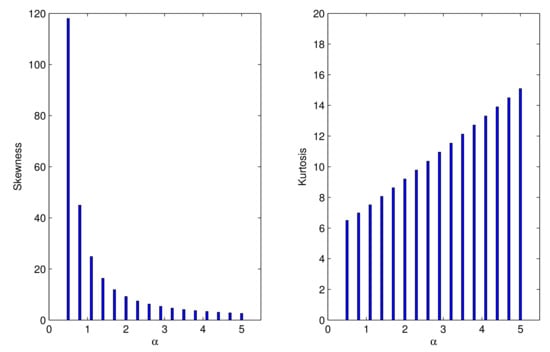

Table 2 gives some moments, variances, and IDs in terms of . Figure 2 displays the plots of the skewness and kurtosis versus . The ID decreases monotonically in , whereas the skewness and kurtosis monotonically increase for .

Table 2.

Moments and ID of the UPA distribution.

Figure 2.

Skewness and kurtosis of the UPA distribution.

2.2. Stochastic Orders of the Parameter

Shaked and Shanthikumar [16] showed that some stochastic orders exist and have several applications. Theorem 1 shows that the UPA distribution is ordered according to the strongest stochastic order, namely, the likelihood ratio () order.

Definition 1.

Consider the two random variables X and Y with respective pmfs and . Then, X is said to be smaller than Y in the order, denoted by , if is non-decreasing in x.

Theorem 1.

Let UPA and UPA. Then for all .

Proof.

We have

and

Clearly, one can note that

□

2.3. Entropy

The Shannon entropy of X can be expressed as

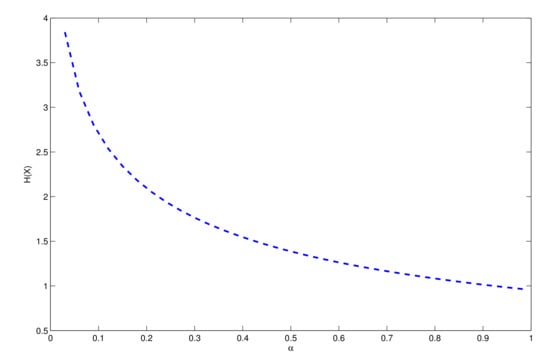

Table 3 gives some values of in terms of the parameter . Figure 3 displays the plot of versus . The entropy is monotonically decreasing for , and it proceeds to zero when becomes larger.

Table 3.

Entropy of the UPA distribution.

Figure 3.

Entropy of the UPA distribution.

2.4. Quantile Function

The quantile function (qf) of the UPA distribution is determined by inverting (6) as

3. Actuarial Measures

In this section, we determine the value at risk (VaR) and tail value at risk (TVaR) of the UPA distribution.

3.1. VaR Measure

3.2. TVaR Measure

The TVaR of X at the security level, say, TVAR, has the form

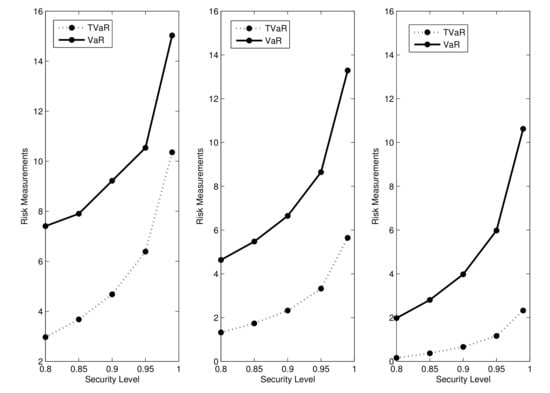

Some VaR and TVaR values for the UPA distribution are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

The VaR and TVaR measures for the UPA model.

The figures in Table 4 and the plots in Figure 4 indicate that the VaR and TVaR measures are increasing functions of .

Figure 4.

Plots of the VaR and TVaR measures for the UPA distribution.

4. Estimation

In this section, the parameter is estimated by eight methods, and their performances are investigated via Monte Carlo simulations. The proposed estimators are determined from the maximum likelihood, moments, proportions, ordinary and weighted least-squares, Cramér–von Mises, right-tail Anderson–Darling, and percentiles methods. For all methods, let be n independent observations from the UPA distribution.

4.1. Maximum Likelihood

The log-likelihood function for comes from (4) as follows:

Then, the maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) of , say, , is determined by maximizing with respect to this parameter as the solution of

which gives if , where .

Under some regularity conditions, the distribution of can be approximated by the distribution, where is the observed Fisher information.

An asymptotic confidence interval for at the level with has the form

where is the -quantile of the normal distribution.

4.2. Moments

The moment estimate (MOE) of follows from given in Section 2.1 as

if . From the central limit theorem,

where

Based on the delta method,

For any , an approximate confidence interval for the parameter comes from (30) as

where .

4.3. Proportions

We define the indicator function (for ) as

Clearly, the proportion refers to the proportion of zeros in the sample, and it is an unbiased and consistent estimate of the probability

Then, the proportions estimate (POE) of [17] follows by solving

which leads to the estimate .

4.4. Ordinary and Weighted Least-Squares

Let be the jth-order statistic in a sample of size n. We adopt lower cases for sample values. It is well-known that and .

The least-squares estimate (LSE) of , , follows by minimizing

in relation to .

The weighted least-squares estimate (WLSE) of , , is determined by minimizing

in relation to , where the weight function is .

4.5. Cramér-von Mises

The Cramér–von Mises estimate (CVME) (see [18,19]) is based on the difference between the estimate of the cdf and its empirical cdf [20]. The CVME of follows by minimizing

with respect to . Further, the CVME of is also obtained by solving

4.6. Right-Tail Anderson–Darling

The right-tail Anderson–Darling estimate (RADE) of follows by minimizing

in relation to . The RADE of is also found by solving the equation

4.7. Percentiles

The percentile estimate (PCE) is obtained by equating the sample percentile point to the population percentile. If denotes an estimate of , the PCE of , say , follows by minimizing

where is an unbiased estimator of and

5. Simulation Study

We conducted a simulation study to evaluate the accuracy of the eight estimators discussed before. We generated samples of sizes , and 300 from the UPA distribution and then calculated the average values of the MLE, MOE, POE, LSE, WLSE, CVME, RADE, and PCE of (AVEs), mean square errors (MSEs), average absolute biases (ABBs), and mean relative errors (MREs) when , and . The ABBs, MSEs and MREs are given by

and

We repeated the simulation 5000 times to calculate these measures for MLE, MOE, POE, LSE, WLSE, CVME, RADE, and PCE from the previous settings. The results reported in Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 were found using the optim-CG routine of R software.

Table 5.

Simulation results of the UPA model for .

Table 6.

Simulation results of the UPA model for .

Table 7.

Simulation results of the UPA model for .

Table 8.

Simulation results of the UPA model for .

The numbers in Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 reveal that the AVEs became closer to the true values of when the sample size n increased, as expected. Further, the ABBs, MREs, and MSEs for all estimators decreased when n increased. Moreover, the MLE and MOE were the best estimators under these criteria. The MLE and MOE were almost identical in terms of the ABBs, MSEs, and MREs, and both had better performances than the other estimators. Additionally, the biases and MSEs of all estimators decayed toward zero when n increased. In summary, the performance ordering of the proposed estimators, from best to worst, was MLE, MOE, WLSE, LSE, POE, PCE, RADE, and CVME. Hence, maximum likelihood was adopted for the work in the next section.

6. Modeling Biological Data

In this section, the UPA distribution is fitted to three real biological datasets and compared with the discrete Burr–Hatke (DBH) [21], discrete Poisson Lindley (DPL) [22], natural discrete Lindley (NDL) [8], discrete Pareto (DP) [5], PA and Poisson distributions according to the model’s ability. The first dataset (Catcheside et al. [23]) refers to numbers of chromatid aberrations, and it was adopted by Hassan et al. [15] for comparing the Poisson and PA distributions. We aimed to test whether the UPA model is a more reasonable choice for these data based on the chi-squared test. Under the null hypothesis, the estimated probabilities were

The estimated expected frequencies were . The results of the chi-square test were reported in Table 9 considering five cells, where

where and are, respectively, the expected and observed frequencies for . Thus, we cannot reject at the 5% significance level, and then the UPA distribution is quite suitable for these data.

Table 9.

Results of the test for the first dataset.

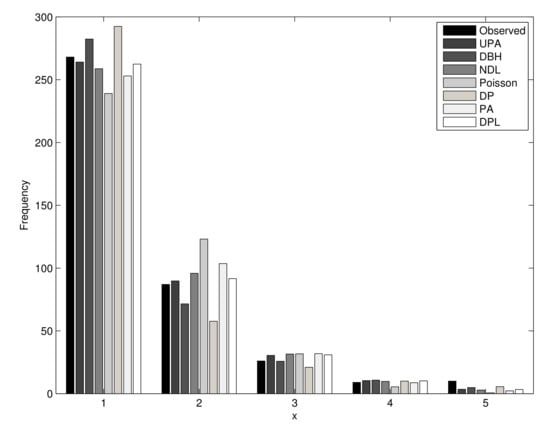

We also report in Table 9 the results of the test for the UPA and other distributions based on the MLE of . The UPA distribution provided the best fit since it resulted in the smallest value. This conclusion can also be confirmed by the log-likelihood test. Figure 5 displays the empirical pmf and seven pmfs fitted to the first dataset, which confirm that the new distribution yielded the best fit to the current data.

Figure 5.

Fitted and empirical distributions for the first dataset.

The second dataset (Catcheside et al. [23]) represents the number of mammalian cytogenetic dosimetry lesions in rabbit lymphoblasts induced by streptonigrin (NSC-45383) exposure—70 3bc g/kg. We fitted the UPA and other distributions to these data.

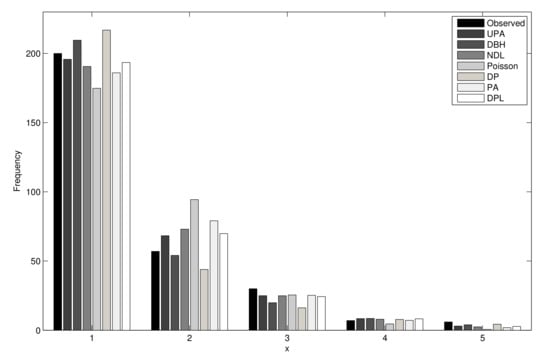

Table 10 reports the results of the test for seven fitted distributions, and Figure 6 displays the empirical pmf and seven pmfs fitted to these data. We have

Table 10.

Results of the test for the second dataset.

Figure 6.

Fitted and empirical distributions for the second dataset.

Then, the hypothesis UPA cannot be rejected at the 5% significance level. Thus, the UPA distribution is a reasonable model for these data.

Based on the tests, log-likelihood values, and Figure 6, we conclude that the UPA model provided a better fit for the second dataset than the other distributions.

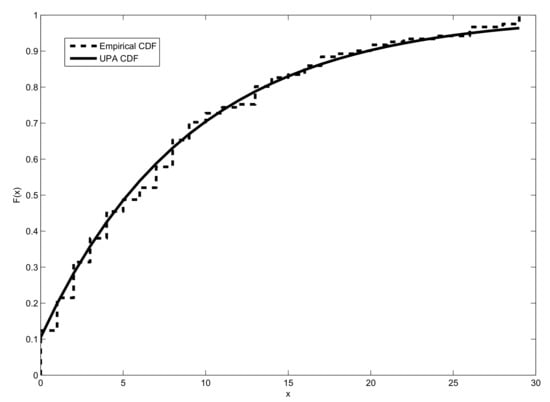

The third dataset refers to counts of daily new COVID-19 deaths of Switzerland between 1 March to 30 June 2021 available at https://github.com/owid/COVID-19-data/tree/master/public/data/ (accessed on 6 July 2021). We adopt these data to show the flexibility of the UPA model comparing to other models based on three criteria: Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and −maximized log-likelihood (). These daily new deaths are: 22, 17, 9, 8, 19, 5, 2, 8, 9, 17, 8, 14, 4, 4, 6, 29, 16, 20, 20, 0, 10, 26, 8, 29, 8, 14, 1, 1, 5, 17, 15, 13, 1, 0, 2, 24, 26, 29, 13, 5, 2, 1, 13, 6, 16, 10, 7, 0, 3, 13, 11, 14, 9, 11, 28, 13, 8, 26, 8, 7, 1, 1, 21, 12, 18, 10, 7, 2, 2, 9, 6, 4, 3, 2, 0, 1, 13, 8, 4, 4, 8, 7, 1, 3, 7, 3, 9, 3, 4, 1, 4, 16, 0, 2, 3, 1, 0, 9, 3, 7, 2, 6, 0, 0, 2, 5, 2, 0, 1, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 4, 2, 0, 0, 3, 2, 4. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic for the UPA model is with a p-value of .

Table 11 reports the estimates of , and the values of AIC, BIC and for the UPA and other distributions. According to the figures in this table, the UPA distribution is more adequate for these data than the DPL, NDL, DPL, PA, DP, DBH, and Poisson distributions. This conclusion is also supported by Figure 7.

Table 11.

Estimates, AIC, BIC, and for the third dataset.

Figure 7.

Empirical and estimated cdf of the UPA distribution for the third dataset.

Some useful probabilities can be easily calculated from the estimated cdf. For example, a researcher would like to know the risk that more than ten deaths occur in Switzerland in just one day during that coronavirus period.

7. Conclusions

New discrete distributions are very important for modeling real-life scenarios since the traditional ones have limited applications in failure times, reliability, counts, etc. We proposed and studied the uniform Poisson–Ailamujia (UPA) distribution, which can give better fits than other discrete distributions, especially when modeling over-dispersed count data. Seven methods were discussed to estimate its parameter, and Monte Carlo simulations showed that the maximum likelihood and moments are the best ones. The flexibility of the UPA model was proven empirically by means of three real biological datasets. Furthermore, the UPA distribution can be extended in some ways. For example, the transmuted UPA, exponentiated UPA, Beta UPA, Kumaraswamy UPA can be defined to provide more flexibility with two and three parameters and to increase the potential applicability of the UPA distribution. It is difficult, sometimes, to measure lifetimes or counts on a continuous scale. In practice, we come across situations, where lifetimes are discrete random variables. For example, the number of days that COVID-19 patients stay in hospital beds, the number of hospital beds occupied by coronavirus patients in a hospital, the number of comorbidities in these patients, etc. We point out examples of epidemiology, but it can be applied in several other areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A. and G.M.C.; methodology, Y.A. and A.Z.A.; software, Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A. and A.Z.A.; writing—review and editing, H.M.A., G.M.C. and A.Z.A.; project administration, H.M.A. and A.Z.A.; funding acquisition, H.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/279), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Editorial Board and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that greatly improved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nakagawa, T.; Osaki, S. Discrete Weibull distribution. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1975, 24, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, W.E.; Dattero, R. A new discrete Weibull distribution. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1984, 33, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. The discrete normal distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2003, 32, 1871–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. Discrete Rayleigh distribution. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2004, 53, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, H.; Pundir, P.S. Discrete Burr and discrete Pareto distributions. Stat. Methodol. 2009, 6, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaraborty, S.; Chakaraborty, D. Discrete gamma distribution: Properties and parameter estimation. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2012, 41, 3301–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noughabi, M.S.; Rezaei, R.A.H.; Mohtashami, B.G.R. Some discrete lifetime distributions with bathtub-shaped hazard rate functions. Qual. Eng. 2013, 25, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Babtain, A.A.; Ahmed, A.H.N.; Afify, A.Z. A new discrete analog of the continuous Lindley distribution, with reliability applications. Entropy 2020, 22, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazah, M.M.A.; Alnssyan, B.; Ahmed, A.H.N.; Afify, A.Z. Reliability properties of the NDL family of discrete distributions with its inference. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Peng, X.; Li, T.; Guo, H. On the Poisson approximation to photon distribution for faint lasers. Phys. Lett. A 2007, 367, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomez-Deniz, E. A new discrete distribution: Properties and applications in medical care. J. Appl. Stat. 2013, 40, 2760–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdoğan, Y.; Kuş, C.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Kınacı, I.; Shafari, F. Uniform-geometric distribution. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2016, 86, 1754–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuş, C.; Akdoğan, Y.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Kınacı, I.; Karakaya, K. Binomial discrete Lindley distribution. Commun. Fac. Sci. Univ. Ank. Ser. Math. Stat. 2018, 68, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.Q.; Gao, L.H.; Chen, C.L. Ailamujia distribution and its application in support ability data analysis. J. Acad. Armored Force Eng. 2002, 16, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.; Shalbaf, G.A.; Bilal, S.; Rashid, A. A new flexible discrete distribution with spplications to count data. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 2020, 19, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Shaked, M.; Shanthikumar, J.G. Stochastic Orders; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S.A.; Khalique, A.; Abouammoh, A.M. On estimating parameters in a discrete Weibull distribution. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1989, 38, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramér, H. On the composition of elementary errors. Scand. Actuar. J. 1928, 1, 141–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mises, R.E. Wahrscheinlichkeit Statistik und Wahrheit; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Luceño, A. Fitting the generalized Pareto distribution to data using maximum goodness-of-fit estimators. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2006, 51, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Morshedy, M.; Eliwa, M.S.; Altun, E. Discrete Burr-Hatke distribution with properties, estimation methods and regression model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 74359–74370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, M. The discrete Poisson–Lindley distribution. Biometrics 1970, 26, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catheside, D.G.; Lea, D.E.; Thoday, J.M. Types of chromosome structural change induced by the irradiation of Tradescantia microspores. J. Genet. 1946, 47, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).