Forty-Year Landscape Fragmentation and Its Hydro–Climate–Human Drivers Identified Through Entropy and Gray Relational Analysis in the Tuwei River Watershed, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Selection and Calculation of the Landscape Pattern Index

2.3.2. Landscape Type and Spatial Distribution

2.3.3. Landscape Fragmentation Composite Index

2.3.4. Gray Relational Analysis

2.4. Analytical Framework

3. Results

3.1. Landscape Pattern Changes

3.1.1. Changes in Land Use Types

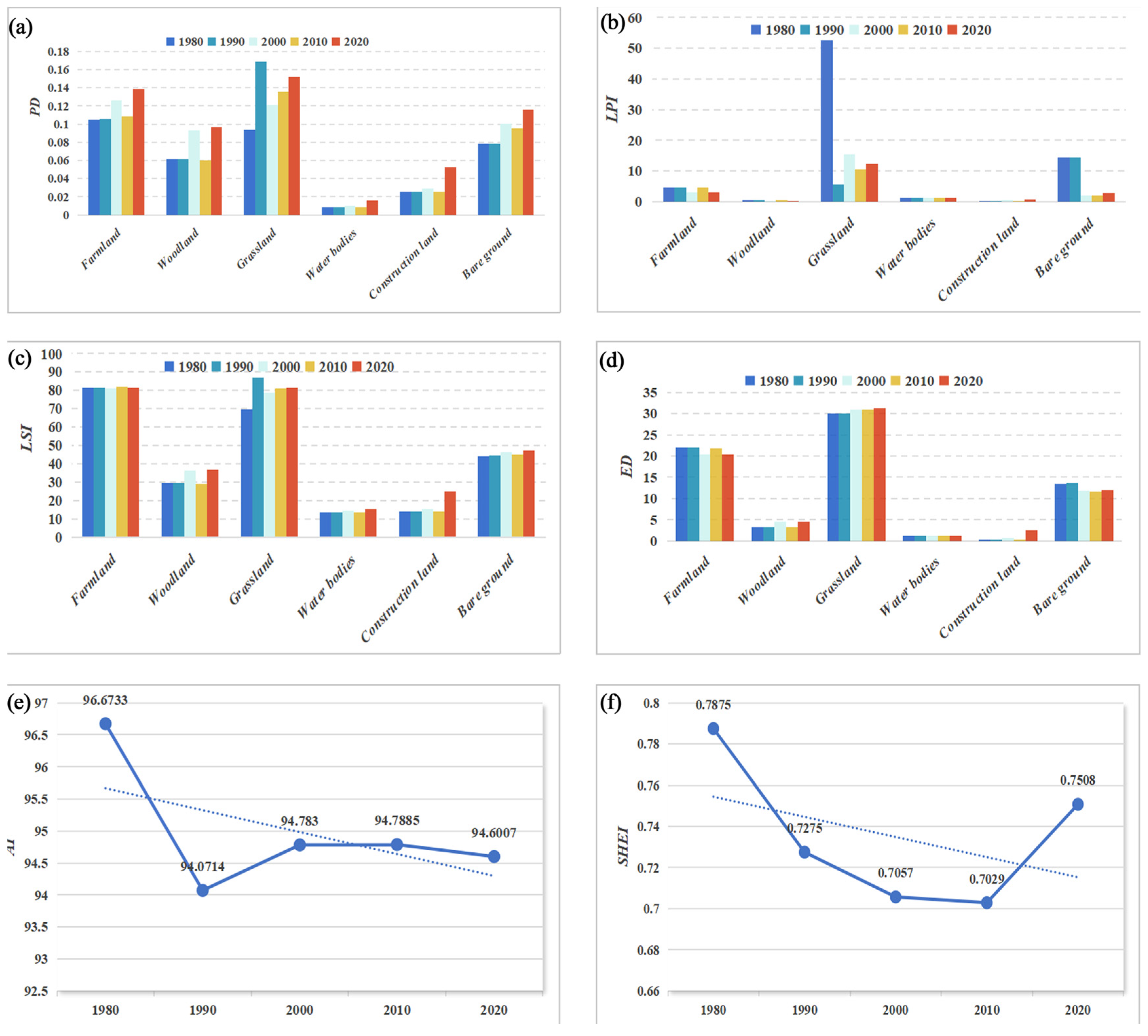

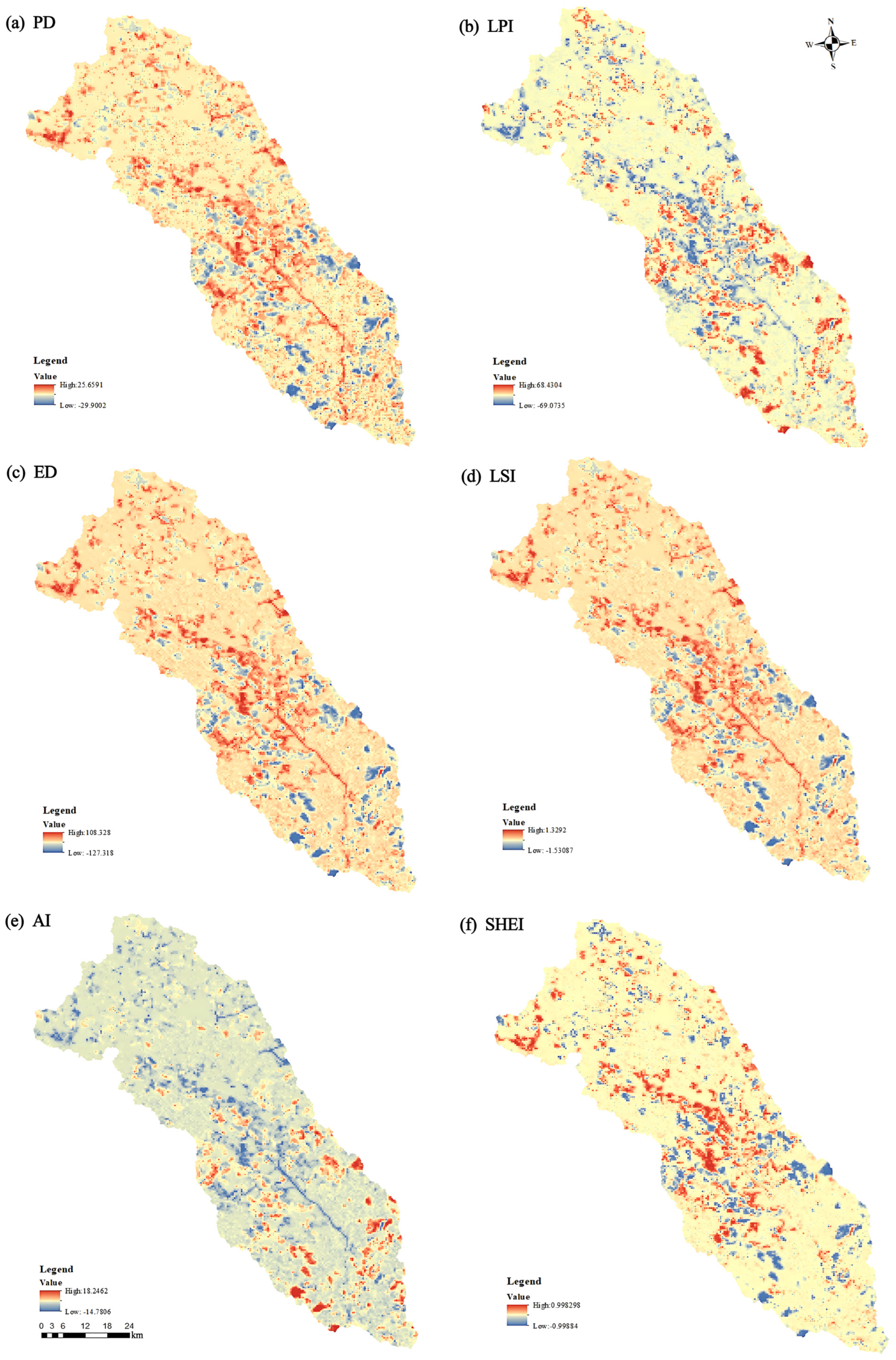

3.1.2. Dynamic Changes in Landscape Pattern Indices

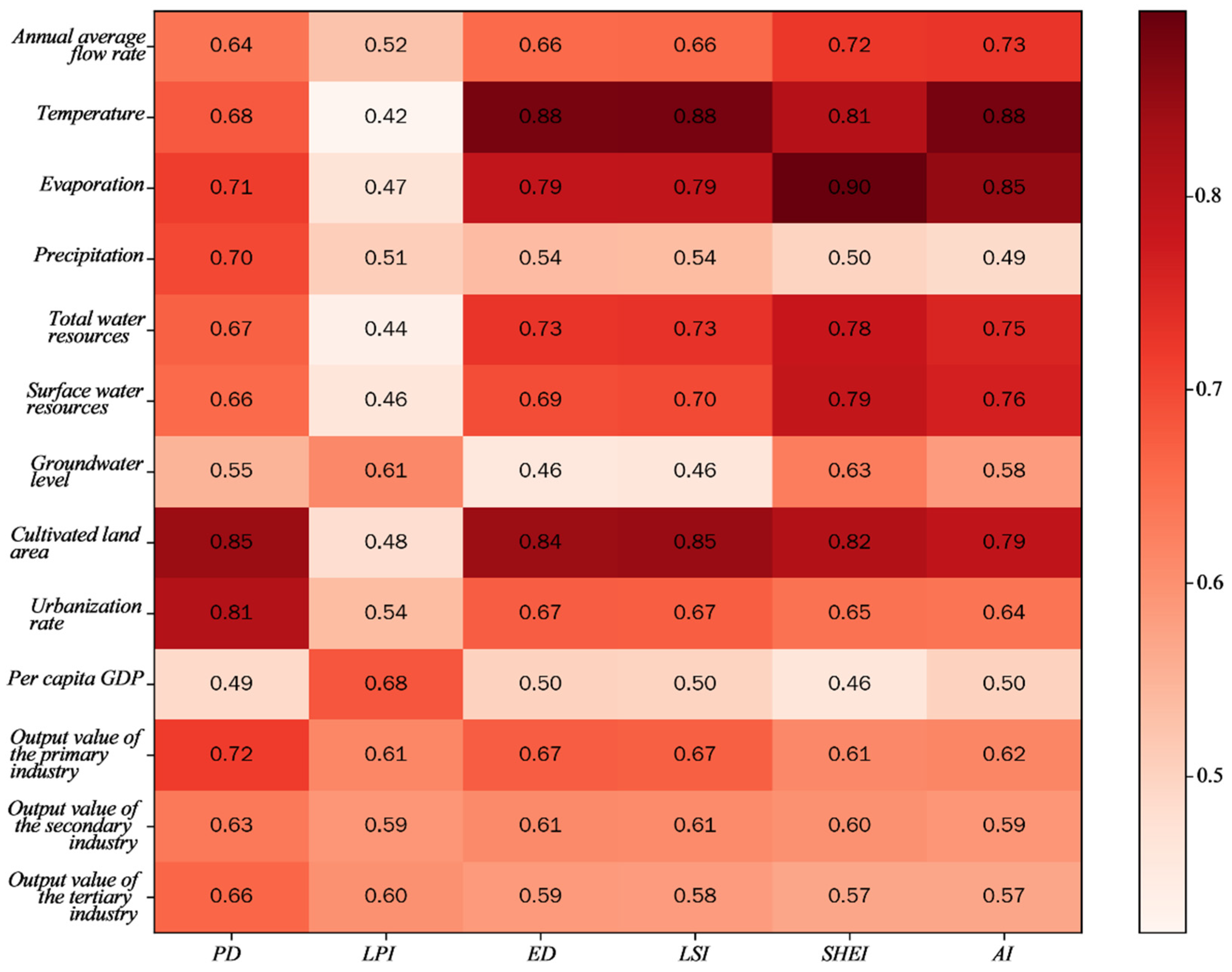

3.2. Identification of Driving Forces of Landscape Pattern Evolution

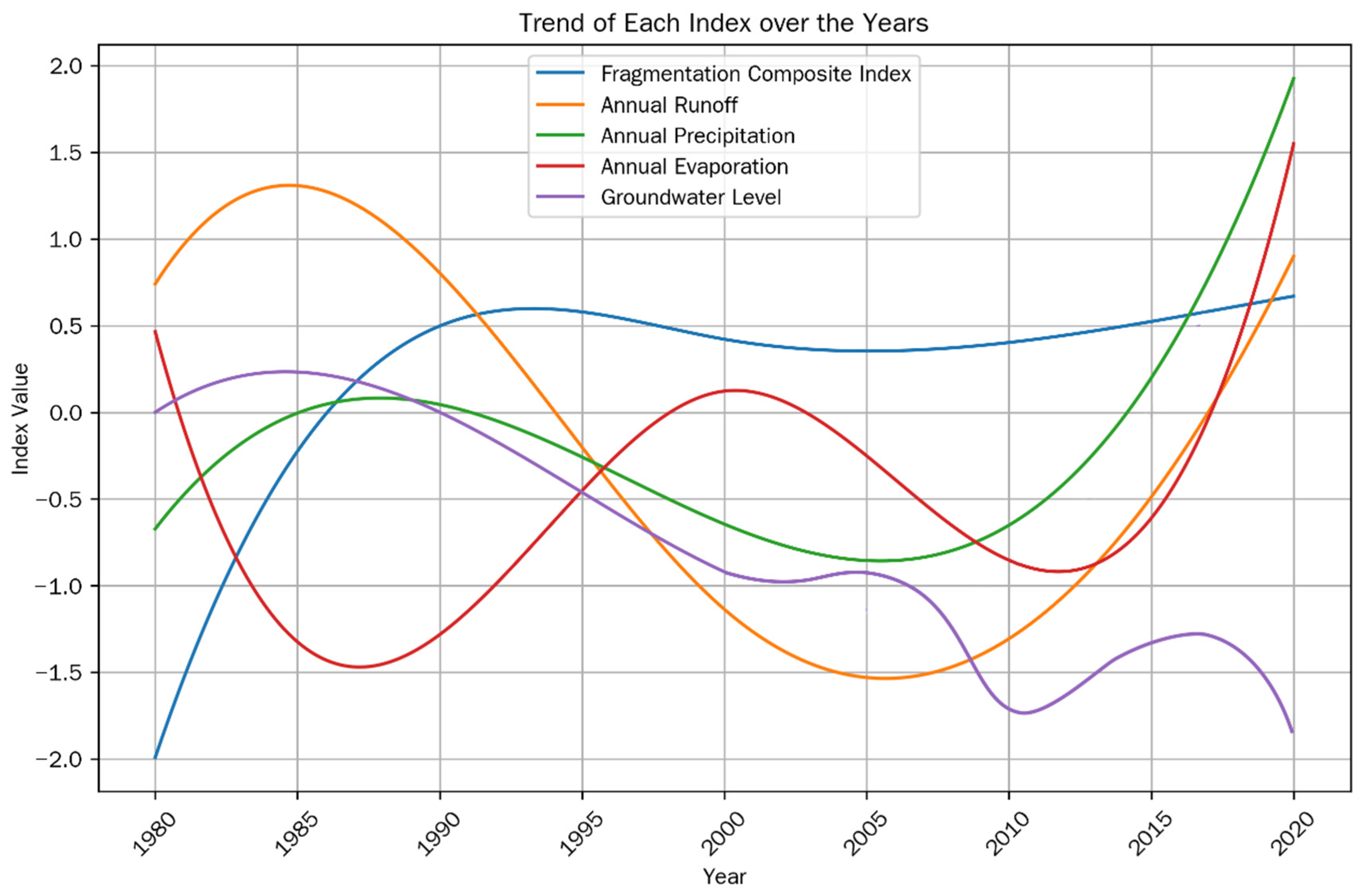

3.3. Investigation of the Relationships Between Landscape Fragmentation and Watershed Hydrological Elements

4. Discussion

4.1. Watershed Land Use Changes

4.2. Analysis of Watershed Landscape Pattern Changes

4.3. Driving Forces of Watershed Landscape Pattern Evolution

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

- Over the 40-year period, the land use structure in the Tuwei River watershed underwent marked restructuring that manifested as the rapid expansion of developed land, marked decreases in cropland and bare land areas, and steady growth of grassland and forestland. The 1990–2010 period represented the peak phase of land use transformation, reflecting a parallel development–restoration spatial pattern under the combined effect of urbanization, resource exploitation, and policy regulation.

- Analysis of landscape pattern indices revealed that landscape fragmentation in the watershed continued to intensify with increasing patch morphology complexity and increased spatial heterogeneity. The phased characteristics of landscape pattern changes closely corresponded with national policies and regional development cycles, demonstrating the interaction between socioeconomic processes and natural landscape patterns.

- GRA revealed that the landscape evolution in the Tuwei River watershed was jointly driven by natural and socioeconomic factors: anthropogenic factors, including the output value of secondary industry and the urbanization rate, served as the dominant forces, whereas changes in temperature and runoff indirectly influenced ecological patterns by regulating surface water–groundwater allocation. The asynchronous phenomenon of increasing surface water and declining groundwater observed after 2000 has become an important mechanism driving the continuous intensification of landscape fragmentation and the decline in ecological connectivity.

- The landscape evolution in the Tuwei River watershed demonstrates a typical climate change–hydrological regulation–ecological feedback chain process. Climatic and hydrological processes establish an ecological foundation, whereas anthropogenic activities amplify landscape fragmentation effects through land use transformation. This interactive pattern within the social–ecological system demonstrates that future watershed governance should enhance the coordinated mechanism of hydrological processes–landscape response–planning regulation, establishing an adaptive management system based on ecological water demand and ecological space connectivity to improve landscape resilience and ecological security in semiarid regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Song, Y.; Hao, J.; Li, Z. Spatio-temporal variation characteristics of water production function in the semi-arid region of the Loess Plateau. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2025, 41, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, T.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Water resource utilization and future supply-demand scenarios in energy cities of semi-arid regions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Hou, Q.; Cao, Y.; Wang, W. Evolution of the landscape ecological pattern in arid riparian zones based on the perspective of watershed river-groundwater transformation. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moursi, H.; Kim, D.; Kaluarachchi, J.J. A probabilistic assessment of agricultural water scarcity in a semi-arid and snowmelt-dominated river basin under climate change. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 193, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paná, S.; Marinelli, M.V.; Bonansea, M.; Ferral, A.; Valente, D.; Camacho Valdez, V.; Petrosillo, I. The multiscale nexus among land use-land cover changes and water quality in the Suquía River Basin, a semi-arid region of Argentina. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wan, H.; Guo, P.; Wang, X. Monitoring critical mountain vertical zonation in the Surkhan River Basin based on a comparative analysis of multi-source remote sensing features. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Du, S.; Li, P.; Yao, Y.; Wang, R.; Teng, K. Analysis of landscape fragmentation and driving forces in semi-arid ecologically fragile areas based on the moving window method. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2021, 38, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ayllón, S.; Martínez, G. Analysis of Correlation between Anthropization Phenomena and Landscape Values of the Territory: A GIS Framework Based on Spatial Statistics. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüpbach, B.; Kay, S. Validation of a visual landscape quality indicator for agrarian landscapes using public participatory GIS data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 241, 104906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yair, A.; Kossovsky, A. Climate and surface properties: Hydrological response of small arid and semi-arid watersheds. Geomorphology 2002, 42, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, J.; Cao, J. Research on the evolution of natural forest landscape pattern in the Changhua River Basin in Hainan. For. Resour. Manag. 2009, 1, 76–79+88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Geng, M.; Wang, M.; Lu, J. Key drivers of spatio-temporal change of land use and its influencing trends: A case study of Wuwei City. Chin. Environ. Sci. 2023, 43, 6583–6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Evolution of water landscape pattern and driving factors analysis of Liangzi Lake Basin. South North Water Divers. Water Conserv. Technol. 2023, 21, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, J.; Dong, C. Regional differentiation and influencing factors of swamp wetland change in Sanjiang plain from 1954 to 2015. Acta Ecol. 2019, 39, 4821–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Tan, C.; Ke, Y.; Zhou, D. Evolution pattern and driving factors of coastal salt marsh wetland landscape pattern in the Yellow River Delta from 1973 to 2020. Acta Ecol. 2024, 44, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.F.; Zhao, D.; Feng, M.F. Spatio-temporal evolution and driving mechanisms of landscape in the Yellow River Basin from 1985 to 2020. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 13, 1611874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Feng, S.; Liu, Y. Land use change and landscape gradient differentiation in the process of urbanization in Kunming. Yunnan Geogr. Environ. Res. 2016, 28, 15–20+47. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OsVNzKNazbRD3hucmSc3n62MatP9itf_8VIf_8d6SstbjzXBlNuGBZnWhUK6N4ODpL43nuzE6Jl3SIKcv_WWa1YzPVVcm-Z7I2MIv4eSRsJgxa65kWp46XWU5SicD9SR7MxCh19m8V-UF7PkSDu-CA4EgdVXbyvF9Jb2btFSTpr0IQvn_H_t6V4Dqu3bK_XAWvnvCzfqW9Q=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Bai, H.; Mu, X.; Wang, S. Effects of soil and water conservation measures on runoff of the Tuwei River. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2010, 17, 40–44. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=bTgd32KJj6sghIUmqfGO-YSKLKeXvbDaJRKou3IOkOzIGw-BUHwyMW6L4diXRQAPNlbeygNd3-FoHkHHenF5-kZqmstw9KI_3Q82_yHHRikkGPJKiOy1lJl2Bb0e9llrjknK41bjFRLoxbkmyrZBf8smqWsAgULvLRKQiE6SwoxekUVR6OEZGIh493OXaHJP&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Yang, F. River-groundwater transformation and ecological effects in the Tuwei River Basin. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2024, 51, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Ma, X.; Yang, X. Evaluation of the current status of epiphytic ecological environment in the Tuwei River Basin. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 2006, 87–91. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=GQPEaosfmU_gLo14vjCX-mH_ZNUzJ9jzY5rhvNaMwqxOFSdhLdzuXjkGyn4yLQXuZh0sJgrU22BbbtERHO3Awa_MaPbKyx5OjJMMRVs7Hu8w-Wc9S_nMlfXgxeHbU6cfes6r_DPL8UUPnSdgkHU3845S6a-QHjo1ogK2JUn3gWWIGG4JOFlkYPYgmIRlgH-Z&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Sun, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.; Gong, W. Analysis of driving factors of runoff attenuation in the Tuwei River Basin. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 310–320. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=GQPEaosfmU9ZYeZEOB8ptsUoK60zyAdE6S9PwUzZkvN1-p4uG-zpqjL9TU3LjytZWBAfCI97F3NH0uFEs8ViOxu5GdYvwRbjW7PMDu8tlfnB1Un5akB_9d4YM55StTeB1PCgBQBDHZsNVQ4T1tMLHdcemr-oz9md5y_6XhOsixOlupZDXGFpNcUCvtlKa9-JCA1FplbV2_4=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Yang, B.; Wang, Q.; Guo, S. Spatiotemporal variation characteristics of soil erosion in the Tuwei River Basin in the wind-sand and sand area of Northern Shaanxi from 1988 to 2013. Soil Water Conserv. Sci. China 2018, 16, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Impacts of climate change on runoff in the Tuwei River Basin. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2011, 29, 184–190. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=bTgd32KJj6vcLJnEjV24o1oyMGK1qhLJms2Q7t5exRASb7hbiY1Y2wdobDTEhHbCe3geLcVRAA615vYg6joIF0Z9LBanzzea452XiHYCAbSIKB_DbN02EwQhARoRzVHscIu9g9cB66mmHI-E2NG2KCriKg4YRq210u7rOl6BjSi-tT6XxnpKe3E28xLL8vmL&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, S. Analysis of the spatiotemporal change pattern characteristics of land use in the Yihe River Basin. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, X. Investigation and impact assessment of the ecological status of Tuweihe wetland in Shaanxi Province. Wetl. Sci. Manag. 2015, 11, 24–27. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=bTgd32KJj6tkkkUf4J5npaGNigiAGm32XoJSskRJ8XD1ObQbF7_V1p4AMSt4A6Tux-o5H8LhTuAMx4X1sldNEok2jfEJKfINO9RJ8hjQgLnA03G7HABecZcIOpnmMqoa1XbinBoDvv1xgSUgBv5XDgjU6C2F1vlivzdRXat0VUNliXL2ApxuDKT2cciqQ3GZc_RvNICN7LQ=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Floyd, M.; East, H.K.; Suggitt, A.J. Evaluating methods for high-resolution, national-scale seagrass mapping in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Shi, Z.; He, G.; Lin, Y.; Xu, R. Construction and Optimization of Ecological Security Pattern in Xishuangbanna Based on Landscape Fragmentation Index. Trop. Geogr. 2022, 42, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Fu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Wang, X. Analysis of landscape pattern changes and driving forces in the Liqiu River Basin in Kangding, Sichuan Province. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2025, 46, 13–20. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=G9uEhVDeKuJ_sPPcuZ9y5HdoP5I9WOU2hcycVkQoVDvHkjuEH94X98GQZC6vuE895MDIDLfawezVAMpb1tpw_Lc8JjJmYehRNfiiSUJWb20EG2DKzGLHZoBPATEMoXXfAcAPdMJtYdmwuD84zXpIdvgQya66cT53sDQ8TPbpafF-4c8o09SJYRjZYX4j3R2R2sy0OK3xxJs=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Du, H.; Ha, E.; Li, M. The urban landscape pattern of Yanji City evolved in 1977~2008. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 31, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Liu, H.; Lu, D. Assessing the effects of land use and land cover patterns on thermal conditions using landscape metrics in city of Indianapolis, United States. Urban Ecosyst. 2007, 10, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Li, Z.; Zou, C.; Qin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Huang, L. Multi-scale effects of landscape types and patterns on plant diversity in Jiangxinzhou: A case study of Fuzhou section of the Minjiang River Basin. J. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 31, 2320–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Z.; Feng, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, W. Analysis of ecosystem service value evolution in Qilian mountains based on land use change. Acta Ecol. 2024, 44, 4187–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, K.; Liu, J. Changes and driving forces of landscape ecological risk in Sanjiang plain from 1976 to 2013. Acta Ecol. 2018, 38, 3729–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, W.; Lan, T. Prediction model of fatty acid content during rice storage in Northeast China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 269–275. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=G9uEhVDeKuKEwqmPsmPRVAEPdjS9s3KQ3_HUdPlu-xXbspswX_1oUBkYga0o4JV-EkSf7o9nTIqXTuTxlThM5CthBVBnFGQG-7MFHSF9uN8VJ_QMCPUJG7f0G24_6gagY6QKcxNgvbrcdgkHfs4UnQQBWMWOXyfBjfDi3sIojq5-dXPoG8y0QkjMQgXh7oNDAKQERWry3hk=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Song, Y.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Mo, H.; Li, Y. Decoding Spatial Vitality in Historic Districts: A Grey Relational Analysis of Multidimensional Built Environment Factors in Shanghai’s Zhangyuan. Land 2025, 14, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lei, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, P. Spatio-temporal Evolution and Driving Factors of Landscape Ecological Risk in the Three Major Basins of Hainan Island. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 1646–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Dan, B.; Feiyu, W.; Bojie, F.; Junping, Y.; Shuai, W.; Yang, Y.; Di, L.; Minquan, F. Quantifying the impacts of climate change and ecological restoration on streamflow changes based on a Budyko hydrological model in China’s Loess Plateau. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 6500–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, L. Spatio-temporal Changes and Influencing Factors of Human Activity Intensity on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Ecol. 2023, 43, 3995–4009. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=wOuTVkq58NkaNGGZi11afde5UNfO-ucKeeKDP1_yfG0H1GWCL4UYmniOyX0_BlLSEv918pwEATBugybXNFhgk4AhkVbxMg62pElWHHjMB7FhYg1upFl1JBLzUb5-RFkEoFw5QS-KfBEMEY4RWDU9wBM37b2LfJSHJhGaKtLlajOuyTiFHsavI6RZmASmMSL6&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Ngwira, S.; Watanabe, T. An Analysis of the Causes of Deforestation in Malawi: A Case of Mwazisi. Land 2019, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, Y.; Bi, Y.; Sun, H.; Ning, B. Study on Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Landscape Ecological Risk in Yushenfu Mining Area from 1995 to 2021. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 270–279. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2402.TD.20230906.1624 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Jin, C.; Xi, J.; Lu, L.; Xu, Y. Research on dynamic change of land use type in Ordos City and its driving force analysis. West. Resour. 2014, 93–95. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OsVNzKNazbRtVryydzHCW6r4ZAqXabzGStHAmkfzvC33YEFz9W46FBuLrKpK-6kEsYmf_MC8OXnoeN-ril8krmTeaLxUU3cH37eafqRUsQ40qBMD8Q_hgDRs7cls2jqOxqPWuEcYCT5GNx6G2NpIKo1LQsnodQNF-QYLgwK_sNyGAe4S8F9MHS6rezbCbx6vVXnr0Qd1Y2Y=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Shi, P.; Luo, J.; Liu, H.; Wei, W. Ecological Risk Analysis of Arid Inland River Basins Based on Landscape Patterns—A Case Study of the Shiyang River Basin. J. Nat. Resour. 2014, 29, 410–419. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Ss1McYY34CcaCgVRggZ8AaBWQ3DRFlbocfygVIcYDWZZBHxQfgfXlEpK7EvUzPB4fEy1BFmophZ2KBbQRc4joq6MAk-WG8vIo-uq6F2K1thwu0DqiXmfIX2uheT8jnQtr0IzrqaQxNc12iGqENpmCubhsvuKUbY5MZrsf0rek48F8yPv3IEAjg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Meng, J.; Jiang, S.; La, B.; Zhang, W. Spatio-temporal Analysis of Land Use Conflicts in the Middle Reaches of the Heihe River Based on Landscape Patterns. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 40, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Xu, G.; Gao, H. Research on the relationship between watershed landscape pattern and water and sediment response based on land use/cover change. Acta Ecol. 2016, 36, 5691–5700. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2031.q.20160105.1547.036 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Huang, Z.; Song, L.; Gao, B.; Jiang, L. Industrial land transfer, industrial selection and urban air quality. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 229–250. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=4QAaWarC2DQX2d-T1VThZzFQmXVVwLUUMTFTJtxtYNLqE7s4slPdIip1qAHYxUspOB7M_fUxBmIqbalN3Zks9I4zvzlKO5gW0tjKl-51feUHiBse-11D_S42HFeG_YUwPFROCBM1TTQs1AXUDy0Y-D-1crxlt87toKCmdsYydP2pNNN41NcTafzzBA56ClpN&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Pan, J. A Study on the Impact of Land Use on Regional Economy and Ecological Environment—A Case Study of Jiangsu Province and Shanxi Province. Rural. Econ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 142–144+183. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=4QAaWarC2DQri0M0lEYoufuV0HRoeNJyvBQFYoOdhhk7OjLASwqISpSllOrfgEE5u484NeOIGn5XvmHK7DZFNKodW0KgdQbsWJ4kKljp1Q87E7X-tOesnSKYCCjHbu8J9_9p9Utn_s2V3VI2jpo8TD5vT0wKxuK9CkhKMY2SyDe00yazdLdpqWFLKTtulSUG&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Ma, Y.; Yin, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Tian, L.; Wu, Z. Identification of spatial conflicts between construction land expansion and ecological land in Urumqi City. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 38, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lang, Q.; Cao, K.; Wang, D.; Yang, K.; Yang, W. Analysis of Dynamic Changes and Driving Forces of Landscape Pattern in the Yongding River Basin from 1980 to 2020. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2023, 13, 143–153. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.5972.X.20220928.1940.008 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Feng, X.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, J. Spatial-temporal changes and driving factors of windbreak and sand-fixation in the ecological security barrier of the Yellow River Basin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, H. Climate Change-Driven Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Landscape Ecological in the Qinling Mountains (1980–2023). Land 2025, 14, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Yang, X.; Sun, W.; Mu, X.; Gao, P.; Zhao, G.; Song, X. Trend and attribution of runoff changes in the hekou-longmen reach of the middle Yellow River. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Du, J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, M. Research Progress on Eco-hydrology of Mountain Forests in Arid Regions. Prog. Earth Sci. 2016, 31, 1078–1089. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=mA0k7fYtKv46LQggF5P06WlpkD7uu1I9JKyKzASSTmGtwZ_94uWu-j6uwfvCE6mnGsAopX3xO3HfUIdjn1UFtem5p6NcBfHGApEYv4eSoAarIGFfVpF0Q2iimizmAx9y4KIuqJzn0hZ8N5tK1smxdexGXttL4Ple3pyJLwpdX0LRoytfDQHBZs9DdOAKtoLt&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Wilcox, B.P.; Basant, S.; Olariu, H.; Leite, P.A.M. Ecohydrological connectivity: A unifying framework for understanding how woody plant encroachment alters the water cycle in drylands. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 934535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; Du, S. Progress and challenges of remote sensing in 40 years of land survey. J. Geo Inf. Sci. 2022, 24, 597–616. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, L.D.; Freer, J.; Coxon, G.; Howden, N.; Bloomfield, J.P.; Jackson, C. Evidence-based requirements for perceptualising intercatchment groundwater flow in hydrological models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, C.; Chen, M.; Ye, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, S. A Spatiotemporal Analysis of the Effects of Urbanization’s Socio-Economic Factors on Landscape Patterns Considering Operational Scales. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X. Calculation of landscape pattern complexity and ecological sustainability analysis of Yanhe River Basin based on Boltzmann entropy. Acta Ecol. 2025, 45, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principles and Perspectives. Acta Geogr. 2017, 72, 116–134. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=G9uEhVDeKuLKEttgl1jm5fYVuNFzRT8d3dccAEXmGf35j7nKR_NWyIaz54pnxHgk_KG02ked0te_Bnwqt7dU4fN9H59-UeNWvhsqEoPyzfnDEXrjH1IOzYHRep_RZapVCTNt1NTt-2uRvRMqIItt-v10l4GKdInCaGsSUUArOb6NZfz4RfoyVUdVv2Txak8No7jH1ao58og=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Land use change and driving factors in rural China during the period 1995-2015. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Alimujiang, K. Research on land use landscape pattern prediction in Hutubi county based on CA-Markov model. Ecol. Sci. 2020, 39, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Gao, F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C. Analysis of the landscape pattern evolution and driving factors of Kokto Sea wetland from 1990 to 2020. Ecol. Sci. 2025, 44, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mei, Z.; Lu, J.; Chen, J. The application of the spatial autocorrelation FLUS model in the multi-scenario simulation of land use change. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2020, 22, 531–542. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=0YYC1NNgyEBk0sZDNXmP9LyGjaEu0AsthDFaqjy8OnzsGRYgVd-6dD9FaNfQ4457P8GMGvPdtk38Gs93chUeor-JyVGrzqdhyDOISkX_Yp172aTYEKnwviwW8HYX5TuwdxM5n-DOB3_vFyPn_bBkuqzoHh1oAgH8btdiAC5UYlWsyjpkeSxtg0xtwp-E9PS7i3Y5C4LCtQk=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F. Simulation and prediction of land use evolution in the Three Gorges Reservoir area based on MCE-CA-Markov. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 268–277. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=0YYC1NNgyECVvg38dwAqXQ_5v8v1hRo7150-6b-t-RMwXgJzmzJk5235rBVfKt3k5j0lgGFiZ3MNCJAb7JDQSAHkTZ0PG87gElfPwgaOJPOFyPU_JVlhTSev0RNJVOyFICo6U7QSRqulI47FP_op-gUVX_aCUZeCkcO6aBZmfU3t79d6BO_AoqitXebLjGuyEgVbMznOSh8=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 April 2025).

| Index Name | Calculation Formula | Evaluation Method and Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum patch index (LPI) | The Largest Patch Index (LPI) typically ranges between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a greater proportion of the largest contiguous patch within the landscape. A higher LPI value may suggest the presence of larger contiguous habitats in the landscape, while lower values often reflect a more dispersed or fragmented landscape pattern. | |

| Patch density (PD) | Patch Density (PD) quantifies the number of patches per unit area. Higher PD values indicate a denser distribution of patches, which is often associated with greater diversity of habitat types or increased landscape complexity. Conversely, lower PD values typically reflect a more homogeneous or structurally simple landscape composition. | |

| Landscape shape index (LSI) | The Landscape Shape Index (LSI) measures the ratio of the actual edge length to the minimum possible edge length of patches, with values always ≥1. Higher LSI values indicate more irregular and complex patch shapes, while values approaching 1 reflect more regular geometric forms. | |

| Edge density (ED) | Edge Density (ED) quantifies the total length of patch boundaries per unit area. Higher ED values indicate greater abundance of landscape edges and increased edge influence, typically associated with heightened landscape fragmentation. Conversely, lower ED values suggest fewer boundaries and better structural continuity within the landscape. | |

| Aggregation index (AI) | The Aggregation Index (AI) ranges from 0 to 1, with values approaching 1 indicating higher aggregation of habitat types. A higher AI value typically suggests that certain landscape types tend to cluster together in the ecosystem, while lower values generally reflect more dispersed or evenly distributed habitat patterns. | |

| Shannon evenness index (SHEI) | The Shannon evenness index (SHEI) ranges between 0 and 1, where m represents the number of landscape types. Values approaching 1 indicate a more even distribution of landscape types across the study area. |

| Serial Number | Step Name | Core Formula | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data standardization | Positive indicators: Negative indicator: | This step ensures comparability across different indicators and establishes a foundation for subsequent calculations. |

| 2 | Calculate index proportion | Conversion of the standardized data into relative proportions was performed for the calculation of information entropy. | |

| 3 | Calculate information entropy | This step quantified the informational value of each indicator to support weight assignment. | |

| 4 | Calculate information utility value | Each indicator’s utility value directly demonstrates its potential contribution to the integrated assessment—higher values signify more critical indicators in the evaluation system. | |

| 5 | Determine indicator weight | Objective weight allocation was implemented for all indicators in the comprehensive index, effectively eliminating subjective deviations. | |

| 6 | Calculate composite index | This approach integrates multi-indicator information into a single value representing the overall landscape condition, thus facilitating both horizontal and vertical comparisons. |

| Year | Index | Farmland | Woodland | Grassland | Water Bodies | Developed Land | Bare Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Area/hm2 | 1,318,830 | 231,115 | 2,181,764 | 128,949 | 13,080 | 1,725,429 |

| Proportion/% | 23 | 4.1 | 39 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 31.4 | |

| 1990 | Area/hm2 | 1,316,920 | 231,111 | 2,175,756 | 129,302 | 13,080 | 1,732,989 |

| Proportion/% | 23.5 | 4.1 | 38.9 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 31 | |

| 2000 | Area/hm2 | 1,302,112 | 232,455 | 2,676,244 | 128,066 | 13,423 | 1,246,867 |

| Proportion/% | 23.3 | 4.2 | 47.7 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 22.3 | |

| 2010 | Area/hm2 | 1,142,259 | 287,512 | 2,817,868 | 123,289 | 30,160 | 1,197,950 |

| Proportion/% | 20.4 | 5.1 | 50.4 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 21.4 | |

| 2020 | Area/hm2 | 1,131,778 | 265,437 | 2,715,926 | 131,981 | 180,767 | 1,173,097 |

| Proportion/% | 20.2 | 4.7 | 48.5 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 21 |

| Year | Index | Farmland | Woodland | Grassland | Water Bodies | Developed Land | Bare Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980–1990 | Area of change/hm2 | −1910 | −4 | −6008 | 353 | 0 | 7560 |

| Rate of change/% | −1.4 | −0.002 | −2.8 | −2.7 | 0 | −4.4 | |

| 1990–2000 | Area of change/hm2 | −14,808 | 1344 | 500,478 | −1236 | 343 | −486,122 |

| Rate of change/% | −1.1 | 0.6 | 23 | −1 | 2.6 | −28 | |

| 2000–2010 | Area of change/hm2 | −159,853 | 55,057 | 141,624 | −4777 | 16,737 | −48,917 |

| Rate of change/% | −12.3 | 23.7 | 5.3 | −3.7 | 124.7 | −4 | |

| 2010–2020 | Area of change/hm2 | −10,481 | −22,075 | −101,942 | 8692 | 150,607 | −24,853 |

| Rate of change/% | −1 | −8 | −4 | −7 | 499.4 | −2.1 | |

| 1980–2020 | Area of change/hm2 | −187,052 | 34,322 | 534,162 | 3032 | 167,687 | −552,332 |

| Rate of change/% | −14.2 | −14.9 | −24.5 | −0.24 | 1282 | −32.01 |

| Annual Average Flow Rate | Temperature | Evaporation | Precipitation | Total Water Resources | Surface Water Resources | Groundwater Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 0.577572577 | 0.905431551 | 0.608963001 | 0.704071996 | 0.647533647 | 0.524665752 | 0.527428201 |

| LPI | 0.700948999 | 0.37926955 | 0.620955205 | 0.586210639 | 0.552295532 | 0.683601417 | 0.782092724 |

| ED | 0.608455347 | 0.886074904 | 0.547416097 | 0.642219979 | 0.626152965 | 0.51090144 | 0.435823886 |

| LSI | 0.608978466 | 0.885770863 | 0.547538736 | 0.642396336 | 0.626390056 | 0.511115533 | 0.436109697 |

| SHEI | 0.746239289 | 0.438838884 | 0.604142253 | 0.695038502 | 0.577828969 | 0.627752015 | 0.702156252 |

| AI | 0.665993318 | 0.382037671 | 0.64862358 | 0.599737581 | 0.572656948 | 0.645087777 | 0.810911446 |

| Cultivated Land area | Urbanization Rate | Per Capita GDP | Output Value of the Primary Industry | Output Value of the Secondary Industry | Output Value of the Tertiary Industry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 0.806153773 | 0.772670728 | 0.561762001 | 0.67828059 | 0.687242382 | 0.707106654 |

| LPI | 0.48579403 | 0.552345561 | 0.661926172 | 0.554954998 | 0.567187692 | 0.571046166 |

| ED | 0.72662545 | 0.701155867 | 0.586777513 | 0.591018884 | 0.722279291 | 0.696206292 |

| LSI | 0.726946012 | 0.701458526 | 0.586466376 | 0.591222019 | 0.722806307 | 0.696602744 |

| SHEI | 0.613255371 | 0.596969565 | 0.565744308 | 0.608434169 | 0.613645027 | 0.618134442 |

| AI | 0.505550862 | 0.573024337 | 0.681192754 | 0.951869394 | 0.697547109 | 0.692187495 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huo, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F.; Fan, Z. Forty-Year Landscape Fragmentation and Its Hydro–Climate–Human Drivers Identified Through Entropy and Gray Relational Analysis in the Tuwei River Watershed, China. Land 2026, 15, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010024

Huo Y, Wang J, Wu Y, Wang F, Fan Z. Forty-Year Landscape Fragmentation and Its Hydro–Climate–Human Drivers Identified Through Entropy and Gray Relational Analysis in the Tuwei River Watershed, China. Land. 2026; 15(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuo, Yuening, Jinxuan Wang, Yan Wu, Fan Wang, and Ze Fan. 2026. "Forty-Year Landscape Fragmentation and Its Hydro–Climate–Human Drivers Identified Through Entropy and Gray Relational Analysis in the Tuwei River Watershed, China" Land 15, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010024

APA StyleHuo, Y., Wang, J., Wu, Y., Wang, F., & Fan, Z. (2026). Forty-Year Landscape Fragmentation and Its Hydro–Climate–Human Drivers Identified Through Entropy and Gray Relational Analysis in the Tuwei River Watershed, China. Land, 15(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010024