1. Introduction

Urban space exhibits intrinsic heterogeneity in both physical structure and functional activities, which often follow scaling laws and can be characterized by power-law or other heavy-tailed distributions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. To investigate the scaling structure within a single city, a topology-based representation is essential [

2]. Natural streets are constructed from continuous street segments, and they can be ranked and subdivided into hierarchical levels, typically revealing that far more short or weakly connected streets exist than long or highly connected ones [

5,

6,

7]. A city is not a tree, as claimed by Christopher Alexander (1965), the street network forms the morphological backbone of the city, shaping both its physical form and the dynamics of urban life [

8]. Huang et al. later extended this idea across multiple cities and demonstrated that street configuration fundamentally shapes urban vitality, accessibility, and social interaction [

9].

Similarly, city hotspots can be delineated and stratified into nested spatial hierarchies guided by Jiang’s wholeness perspective [

10]. Urban hotspots represent concentrations of human activities or built-environment elements such as POIs, population density, or nighttime lights [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Detecting these hotspots from large geospatial datasets allows researchers to capture the city’s underlying living structure, characterized by far more small centers than large ones [

15,

16,

17]. From the wholeness perspective, these hotspots are not isolated entities but interconnected centers that interact across multiple spatial scales [

18,

19]. Together, they constitute a coherent whole in which the relationships among centers, rather than their individual attributes, define the city’s overall complexity and vitality.

Prior studies have shown that urban mobility exhibits Lévy-flight-like heavy-tailed patterns [

20,

21], and that human movement flows are closely linked to the scaling properties of street networks [

7,

22]. However, few studies have examined how these structural hierarchies relate to the spatial distribution of urban functions across scales. Points of Interest (POIs), reflecting aggregated commercial, public service, and other urban functions, provide a direct proxy for localized activity patterns. Ai et al. used POI data to classify urban functional agglomerations at the block level [

23], while Li et al. monitored the evolution of urban functional zones using multi-source POI data [

24]. Yet, limited work has integrated urban form and function into a unified multi-scale framework to examine their coupling effects.

A fractal or scaling perspective, which captures the self-similarity and complexity of nested spatial structures, offers new insight into how physical form relates to functional distribution. Identifying and comparing hierarchical street and hotspot clusters helps reveal how structural layers co-organize POI locations and urban activities. Derudder et al. identified polycentric structures and emphasized the importance of accurate identification of dominant centers [

25], and Ren et al. showed that such structures can be further decomposed into nested intra-urban cores [

26].

Accordingly, this study examines whether and how the hierarchical scaling of streets corresponds to the spatial distribution of POIs within a single city. Accordingly, this study examines whether and how the hierarchical scaling of streets corresponds to the spatial distribution of POIs within a single city. We generated natural streets and extracted street nodes for hotspots, which were then hierarchically classified using head/tail breaks based on street connectivity and number of street nodes. Unlike previous studies that identify hotspots only once or at a single scale, we recursively generated hotspots using street nodes to capture the inner heterogeneity of spatial distribution, allowing finer-scale structures to emerge through multiple recursions [

16,

17]. POI data were spatially linked to streets by nearest distance and assigned to corresponding hotspot levels.

From the street perspective, we conducted multilevel correlation analyses between street connectivity and the number of nearby POIs across hierarchical street levels. From the hotspot perspective, we evaluated correlations between the number of street nodes and POIs within each recursively derived hotspot. Our results show that POI locations are not randomly dispersed but are shaped and constrained by the multilevel street configuration. Highly connected streets and dense node clusters act as spatial anchors for POI concentration, reflecting a nonlinear and dynamic coupling between urban form and function.

This study makes three key contributions. First, it integrates street networks and TIN-based hotspots into a unified multiscale analytical framework that jointly models morphological hierarchies (from natural streets and street-node hotspots) and functional hierarchies (from POI distributions). Second, it provides theoretical insight by demonstrating that POI locations are shaped and constrained by the multilevel configuration of the street network. Third, it offers empirical evidence that street-based and hotspot-based hierarchies exhibit similar scaling patterns and that the strength of form–function coupling varies systematically across levels. These findings reveal that Shenzhen’s structural and functional complexity co-evolves through consistent multilevel organization, offering a new analytical lens for understanding urban systems.

The content of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the study area, describes the datasets used, and details the procedures for deriving natural streets, street nodes, and POI clusters, followed by the methodological framework for hierarchical scaling analysis.

Section 3 presents the empirical results, including the power-law characterization of street and POI hierarchies and the multi-scale correlation analysis between street connectivity and POI distribution.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the observed structural–functional coupling from the perspective of living structure theory and highlights how hierarchical form–function alignment informs our understanding of urban complexity.

Section 5 concludes the study by summarizing major findings, outlining contributions, and proposing future research directions.

3. Experiments and Findings

3.1. The Scaling Structure of Natural Streets and Street Junctions

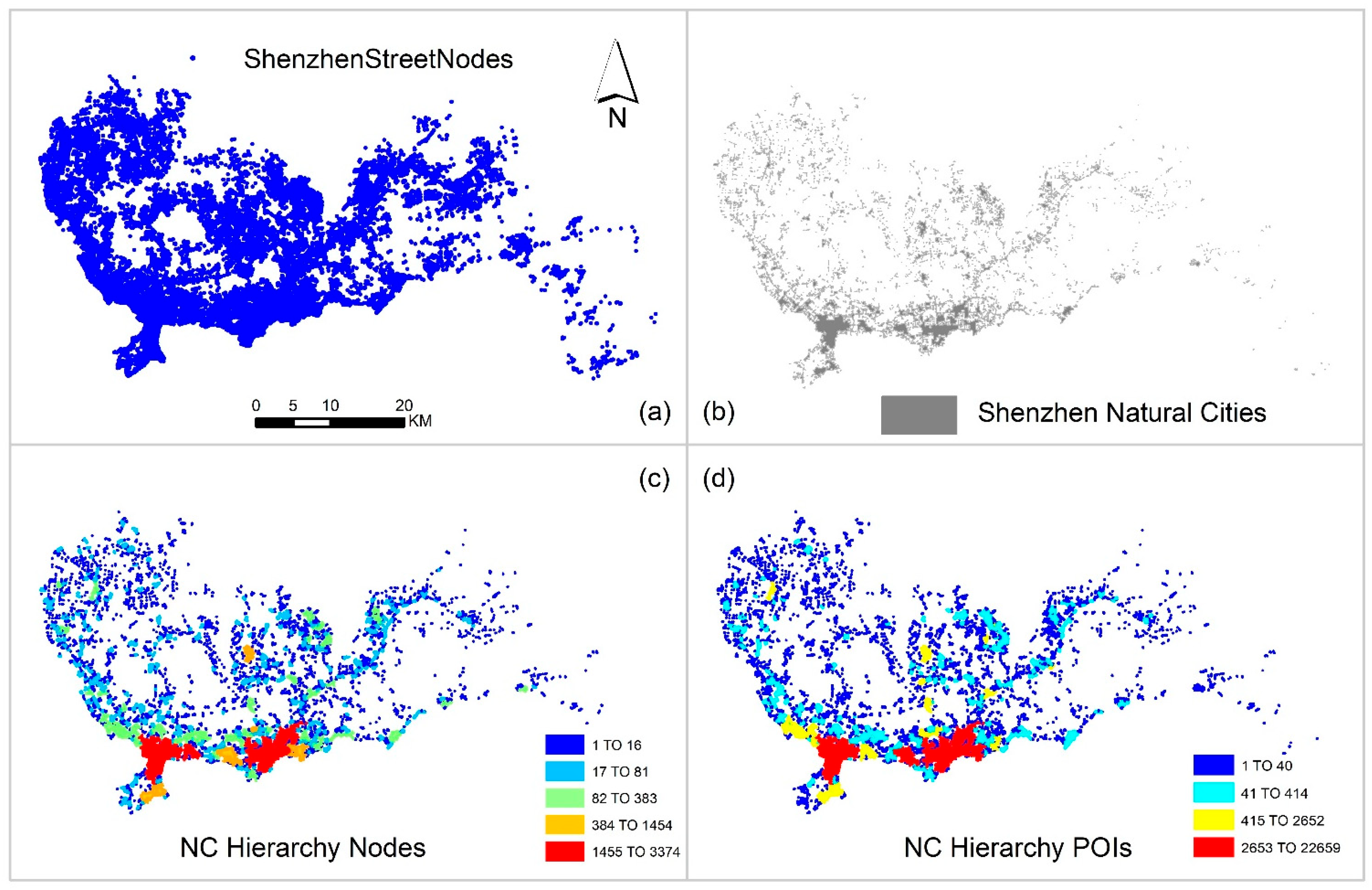

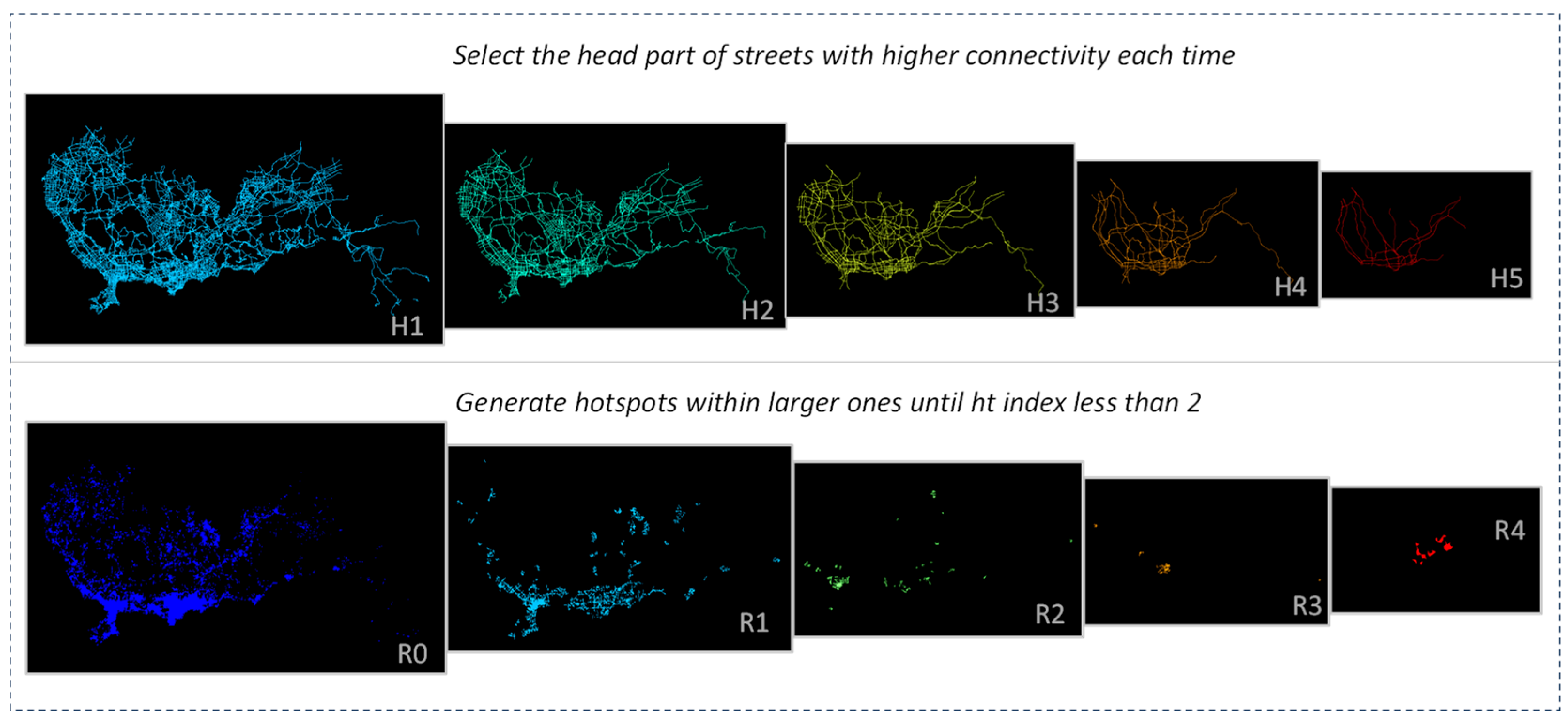

The hierarchical scaling analysis of the Shenzhen streets reveals that both the street structure and its associated node and POI distributions exhibit a clear multi-level organization consistent with living structure theory. As shown in

Figure 4, the natural streets derived from OpenStreetMap data form a continuous spatial hierarchy with an ht-index of 6, indicating that the distribution of street connectivity spans six hierarchical levels. This relatively high ht-index suggests a deeply nested structure in which a few long, highly connected streets act as the primary backbone of the city, while the majority consist of progressively smaller and less connected streets. The color-coded hierarchy maps demonstrate that these major streets primarily run through the central and western parts of Shenzhen, forming the main structural skeleton that supports urban movement and accessibility.

When the analysis is extended to POI-based street hierarchies, the results show a slightly lower ht-index of 5, reflecting that the distribution of functional density (POI count) also follows a heavy-tailed pattern but with one less hierarchical level than the topologic street network. This indicates that while the morphological complexity of the street system reaches six levels, the functional and topological hierarchies (as reflected by POIs and nodes) are marginally simpler, suggesting a strong coupling but not a perfect alignment between urban form and function. The consistent scaling between the two confirms that both physical and functional aspects of the city conform to the principle of “far more small things than large ones,” reinforcing the living structure nature of the urban system.

As shown in

Figure 5, the analysis of street-node clusters and intra-urban hotspots reveals ht-indices of 5 and 4, respectively. The street-node clusters (ht = 5) exhibit a hierarchical nesting pattern similar to that of the street network, where dense clusters of intersections emerge around the city’s main structural axes. In contrast, the intra-urban hotspots from street nodes (ht = 4), joined from the distribution of POIs, display a slightly shallower hierarchy, suggesting that urban functions are concentrated in fewer dominant centers. This implies that Shenzhen’s functional hotspots are more centralized compared to the more evenly scaled geometric and topological structures. Collectively, these findings illustrate that Shenzhen’s Street and node hierarchies are deeply structured and spatially coherent, while its functional hierarchy, although still scaling, is more concentrated, reflecting the interaction between urban form, connectivity, and functional intensity across multiple spatial scales.

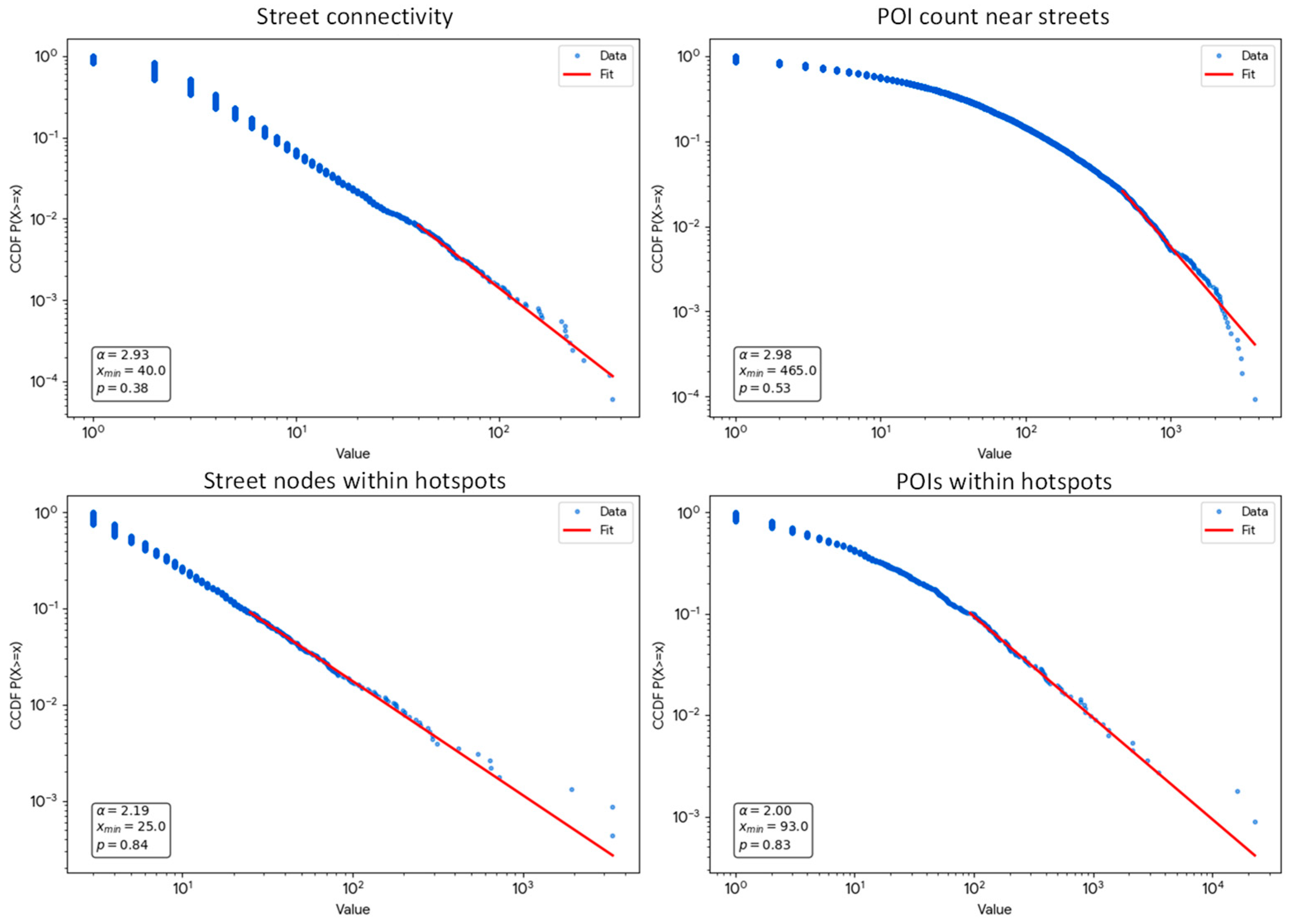

The power-law analysis reveals consistent scaling behavior across both the street network and node-based hotspot systems in Shenzhen, underscoring their hierarchical and self-organizing nature (

Table 2,

Figure 6). For the street network, street connectivity exhibits a power-law exponent of 2.93 (α = 2.93) and a lower bound of x

min = 40. It indicates a scale-free structure in the tail, although the relatively high exponent implies a steeper hierarchy where super-connected streets are somewhat rarer than in systems with lower scaling parameters. Similarly, street-based POIs follow a power-law distribution with α = 2.98, suggesting that functional activities are more unevenly distributed, concentrating along a small number of major streets.

For the node-based clusters, both structural and functional properties also demonstrate clear scaling regularities. The cluster node size has an exponent of α = 2.19, while the cluster POI count yields α = 2.00. The scaling exponent of node clusters is close to the critical value of 2.0, align well with empirical findings in complex urban systems and indicate that many small clusters coexist with a few dominant centers, forming a nested and hierarchical configuration. Overall, these results confirm that both the physical street structure and the functional activity distribution in Shenzhen follow power-law scaling, reflecting the city’s underlying living structure of high hierarchies.

When compared with findings from other Chinese cities, the scaling exponents observed in Shenzhen show an interesting duality. The exponents for node- and POI-based clusters fall well within the typical range of α = 2.0–2.2, reported in previous studies on urban street and hotspot systems [

7,

13,

26]. This range is widely interpreted as a signature of critical complexity, a balance between complete disorder and rigid uniformity. In contrast, the exponents for street connectivity and street-based POIs are higher than the typical range. This may suggest that while the functional “living structure” of clusters evolved towards a robust bottom-up hierarchy, the physical street network exhibits a stronger decay in the tail, likely consistent with Shenzhen’s rapid, top-down urban expansion which limits the formation of extremely high-connectivity hubs compared to organic evolution.

3.2. Multi-Scale Correlation Analysis for Streets and Hotspots

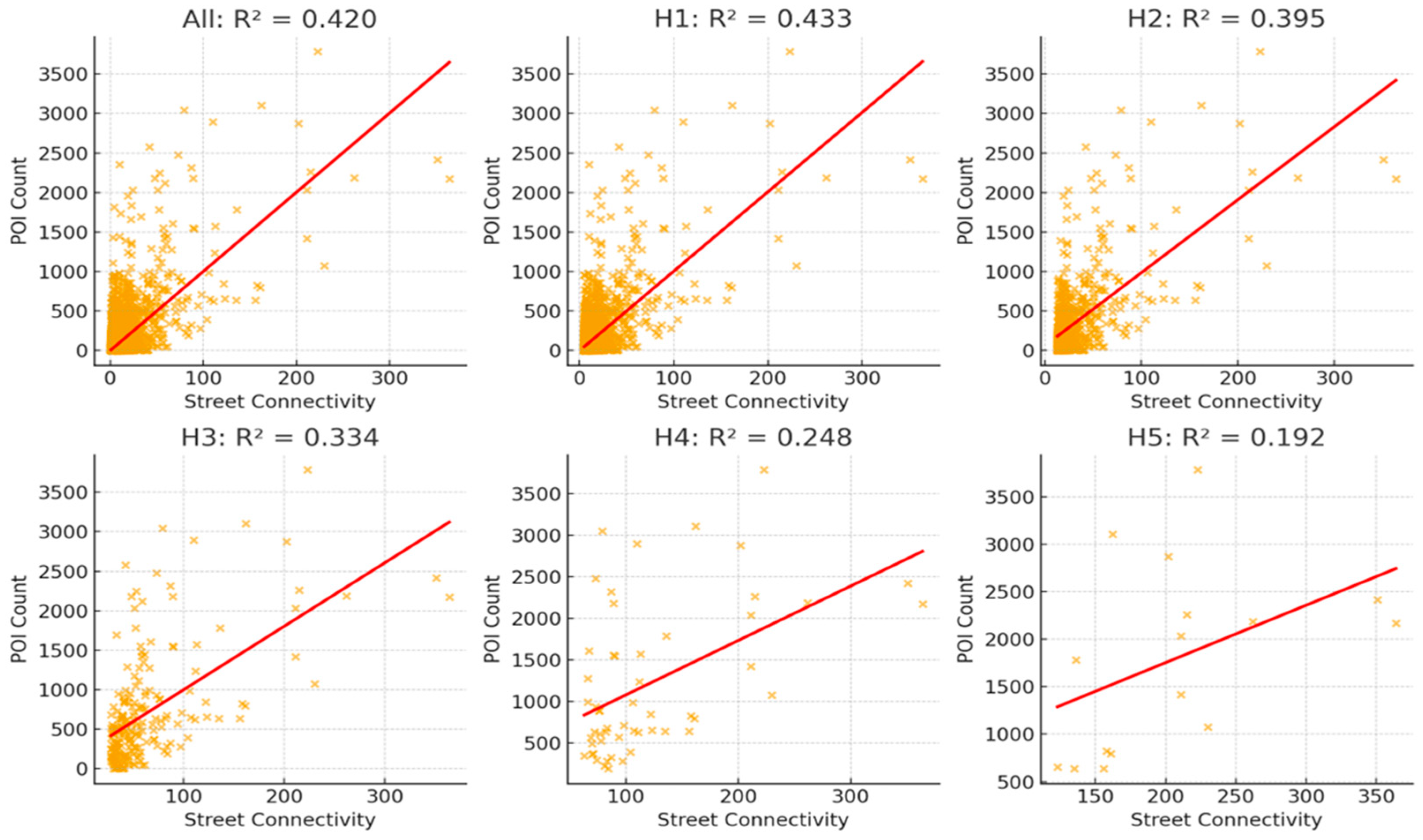

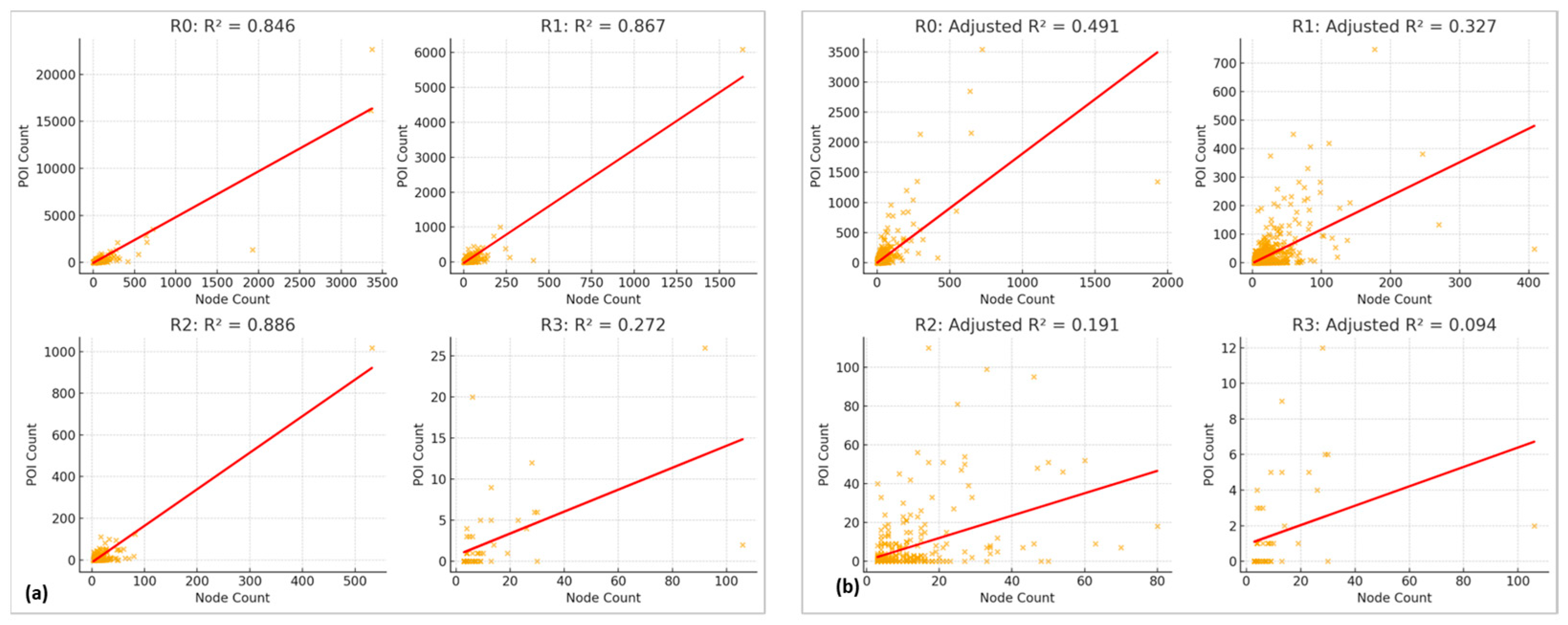

In this study, we conducted correlation analyses at multiple scales induced by head/tail breaks on the street connectivity and number of POIs within hotspots as shown in

Figure 7. The streets are divided into five levels, and we conducted correlation at four largest levels. For the spatial cluster or hotspots, we recursively divided hotspots at four recursions. The correlations between number of nodes and POIs were calculated. The multi-scale correlation analysis reveals a statistically significant association between street connectivity and the density of nearby Points of Interest (POIs) across hierarchical levels of the street network (

Table 3).

For the overall dataset, a moderate positive correlation is observed (Spearman r = 0.27, p < 0.001) with a linear fit of R2 = 0.42, indicating that streets with higher topological connectivity generally host denser concentrations of POIs. This result supports the hypothesis that urban form and function are interrelated, where well-connected streets tend to attract more urban activities due to their structural accessibility and spatial prominence.

Across the hierarchical levels derived from head/tail breaks, the strength of correlation varies systematically (

Figure 8). The correlation increases from H1 (r = 0.40) to H2 (r = 0.53) and peaks at H3 (r = 0.55), while slightly declining at H4 (r = 0.45). Correspondingly, the R

2 values range between 0.25 and 0.43, suggesting that although the linear relationship remains consistent, the explanatory power differs among scales. The stronger association at intermediate levels (H2–H3) implies that these scales represent the most functionally active and structurally coherent components of the urban network, where street connectivity most strongly governs the spatial distribution of POIs.

For the correlations within hotspots, the statistical analysis revealed a consistent and meaningful relationship between street-node density and POI (Point of Interest) density across the four regional levels (R0–R3) (

Figure 9). The results of both Spearman’s rank correlation and linear regression analysis confirm that areas with denser street networks tend to host a higher concentration of functional activities (

Table 4).

Spearman’s coefficients (r = 0.47–0.55, p < 0.001) indicate a moderate to strong monotonic relationship across all groups, suggesting that the association between urban form and function remains robust even after removing extreme outliers. This consistency implies that the spatial coupling between structural and functional hierarchies is an intrinsic property of the city rather than an artifact of extreme values.

The linear fit results show that the coefficient of determination (R2) and adjusted R2 values decrease progressively from R0 (0.85, 0.49) to R3 (0.27, 0.094), indicating that the strength of the linear relationship weakens toward peripheral or higher-level subregions. The central regions (R0–R1) display strong linear form–function coupling, where street-node density explains a substantial proportion of POI variation, while outer regions (R2–R3) exhibit more complex, nonlinear spatial patterns. Taken together, these results suggest that Shenzhen’s urban system exhibits hierarchical scaling behavior, where the correlation between urban form and function is strongest in core areas and becomes more irregular yet remains monotonic toward the periphery.

We noted that the correlation decreases at the finest hierarchical levels for both the street hierarchy and the hotspot hierarchy. At these local scales, spatial patterns become more evenly distributed and heterogeneous, and functional differences between small units are less pronounced. This increased spatial randomness weakens the monotonic relationship between connectivity and POI intensity. The reduction in correlation therefore reflects the expected transition from strong structural organization at higher levels to more context-dependent and irregular patterns at local scales.

Overall, the findings highlight the scale-dependent coupling between urban form and function, emphasizing that the relationship between connectivity and functional intensity varies along the structural hierarchy rather than being uniform. Mid-level streets appear to play a crucial bridging role, linking the global arterial framework with localized street networks and facilitating the transition between large-scale structural organization and small-scale functional diversity. This scale-sensitive behavior demonstrates the hierarchical nature of urban systems and underscores the importance of multi-level analysis in understanding urban complexity. By capturing how the interaction between street structure and activity distribution strengthens or weakens across scales, the results provide empirical evidence for the living structure of Shenzhen, in which order and adaptability coexist through nested spatial hierarchies.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that Shenzhen’s urban form and function are jointly structured by multilevel scaling hierarchies, revealing a coherent living structure that manifests across the street network, street nodes, and the spatial distribution of POIs. The results show that natural streets, street-node clusters, and POI hotspots all follow heavy-tailed distributions, with ht-index values between 4 and 6, demonstrating that each component of the urban system is highly hierarchical and deeply heterogeneous. These findings align with the core tenets of living structure theory proposed by Alexander [

15] and formalized by Jiang [

18,

19,

30], namely that cities evolve through nested, mutually reinforcing centers rather than uniform or randomly distributed spatial elements.

The strong correlations observed at higher and intermediate hierarchical levels reinforce this interpretation. More connected streets and denser street-node clusters consistently coincide with higher concentrations of POIs, demonstrating that the functional layout of the city is fundamentally conditioned by its underlying morphological hierarchy. These results echo earlier findings that street configuration shapes human activities and urban vitality [

7,

9,

22,

26]. In Shenzhen, major streets act as spatial anchors that structure not only movement but also functional agglomerations. This spatial anchoring effect reflects the principle of “far more small things than large ones,” manifested as many small local centers embedded within a few dominant large centers.

These findings empirically support Alexander’s concept of living structure by showing that hierarchical centers emerge not only in the physical street system but also in functional spatial distribution. Natural streets and POIs each generate nested centers that reinforce one another across scales, revealing a shared spatial logic. This multiscale alignment extends earlier mobility-based research by demonstrating that stationary economic and service functions follow similar structural constraints. It also bridges network-based and hotspot-based perspectives, illustrating that both linear routes and point clusters contribute to the city’s recursive spatial order. The street network, urban hotspots, and the living structure together form the essential morphological and functional framework of a city.

The method of this study resonates strongly with Lynch’s (1984) notion of “good city form” which emphasizes legibility, vitality, and a sense of place as key dimensions of urban quality [

35]. The living structure perspective extends this idea by suggesting that the degree of legibility and vitality in a city arises naturally from its underlying scaling hierarchy—a configuration in which a few large, well-connected centers coexist with many smaller, supporting ones. Thus, a “good city” is not merely one that is visually ordered or functionally efficient, but one whose street network and hotspots are arranged in a living, coherent hierarchy that fosters both accessibility and emotional attachment. Integrating Lynch’s qualitative vision with quantitative measures of living structure offers a promising pathway toward cities that are not only efficient and sustainable but also psychologically and aesthetically whole.

An additional noteworthy insight emerging from this study is the bidirectional perspective between form and function. While much of urban analysis traditionally evaluates how street form shapes functional patterns, our results show that functional clusters derived solely from POI distributions can themselves serve as an effective lens for revealing the underlying urban form. The hierarchical structure of POI-based hotspots mirrors, to a remarkable degree, the hierarchical morphology of the street network. This suggests that urban function is not merely an outcome of form, but also a powerful indicator of form—particularly in dense, rapidly evolving cities like Shenzhen.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Shenzhen’s urban form and function are jointly structured by nested scaling hierarchies, providing clear evidence that the spatial organization of POIs is closely linked to the city’s street configuration. Both natural streets and POI clusters follow heavy-tailed distributions, reflecting a living structure composed of multiple hierarchical levels. Although the street network exhibits a deeper hierarchy than the POI system, their overall scaling consistency indicates that major streets and dense street-node clusters serve as structural anchors for functional aggregation. Correlation analyses further reveal that highly connected streets consistently attract more POIs, with the strongest associations observed in mid- and upper-level structural layers. At finer scales, the coupling becomes weaker and more nonlinear, reflecting more diverse and context-specific functional patterns in peripheral or weakly connected areas.

In summary, this study makes three key contributions. First, it develops a unified multiscale analytical framework integrating natural streets, street nodes, head/tail breaks, and TIN-based clustering to jointly model morphological and functional hierarchies. Second, it provides theoretical evidence that POI distributions are strongly conditioned by the underlying street hierarchy. Third, it shows that both streets and hotspots exhibit consistent scaling behaviors and that the strength of form–function coupling varies systematically across hierarchical levels. These findings suggest that Shenzhen’s morphological and functional systems co-evolve as parallel living structures, offering important implications for planning strategies that seek to align spatial configuration with functional needs.

Future research should expand beyond morphology to incorporate socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioral dimensions. Integrating spatial network metrics with data on income, mobility, land use, or well-being could deepen understanding of how urban form shapes accessibility and opportunity. Additionally, the use of AI-based and generative models may enable dynamic simulations of how changes in street configuration or hotspot distribution influence urban evolution over time.