Abstract

Conservation agriculture continues to be promoted in developing nations as a sustainable and suitable agricultural practice to enhance smallholder productivity. A look at the literature indicates that this practice is successful in non-African countries. Thus, this research sought to test whether minimum tillage (MT), a subset of conservation agriculture, could lead to a significant impact on smallholder households’ welfare in Southern Tanzania. Using cross-sectional data from 608 randomly selected smallholder households, we applied propensity score matching to determine the effects of adopting minimum tillage on smallholder households’ per capita net crop income and labor demand. Our results indicated that minimum tillage adoption has positive impacts on smallholder households’ per capita net crop income. Further, it reduces the total household labor demands, allowing households to engage in other income-generating activities. However, the adoption rate of minimum tillage is in the early majority stage (21.38%). Thus, we propose the government to support household credit access and extension-specific information to improve the probability of adopting minimum tillage.

1. Introduction

Climate change and its adverse effects on agricultural production have been the topic of discussion globally. The observed temperature and rainfall volatility and the consequent decline in agricultural productivity have led to the promotion of various climate adaptation technologies in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1]. Conservation farming has been significantly endorsed to increase agricultural productivity, and stabilize crop yields under seasonal variations. In Southern Tanzania, one of the prioritized climate adaptation technologies is minimum tillage, an element of conservation agriculture [2]. The current wave of debate indicates that minimum tillage and other conservation farming practices are the remedy for the diminishing agricultural productivity induced by climate change and variability [3]. Therefore, most policy makers and governments have invested considerably in promoting these conservation farming practices [4]. However, debates about the effects of minimum tillage principles have led to questions about their suitability for smallholder farmers [5].

Most of the climate change adaptation approaches have had a positive impact on smallholder welfare [6]. However, several pieces of research critique the practical effectiveness of the conservation farming practices for the smallholder farmers in SSA, including Tanzania [4,5]. Additionally, researchers have questioned conservation farming’s ability to improve soil structure and aeration [3,7]. There are questions about the practical applicability of conservation farming in the diverse smallholder farming households context [8]. For instance, [9] concluded that, when addressing the fundamental productivity challenges, conservation farming is not the primary step. Further, [10] outlined substantial conclusions on why smallholder farmers may not gain from conservation farming. Similarly, there is limited information on what type of conservation farming leads to significant outcomes. As a result, there is a need for researchers to outline the components of conservation farming they are dealing with when highlighting the farmers’ benefits, such as crop yield gains, soil improvement, and labor- and cost-saving.

Minimum tillage involves the slightest soil disturbance, either through ripping or planting in basins. It is also a dry-season land preparation method and consists of planting crops into the soil’s vegetative cover with less soil surface-breaking [11]. The fundamental principles of minimum tillage suggest a restriction of soil disturbance to a particular area, leading to a minimum soil turnover [12]. In essence, it improves the soil structure, influences plant growth and development, thus augmenting productivity [13]. There is scanty empirical literature on the effects of minimum tillage on smallholder farmer welfare. Hence, the extent to which minimum tillage can improve household wellbeing has not been analyzed extensively in the existing literature [9,10,11,12].

Therefore, in this paper, we address two research questions; that is, what factors determine the adoption of minimum tillage among the smallholder horticultural crop producers in Southern Tanzania, and the subsequent impacts this farming approach has on their welfare proxied by per capita net crop income and labor demands. We focused on smallholder horticultural farmers using minimum tillage in at least one of their plots. Our analysis in this paper complements the existing literature in various ways. First, it is imperative to evaluate trade-offs that might be created before adoption of minimum tillage is scaled up. This study also contributes to the literature by identifying factors that shape farmers’ decisions to adopt minimum tillage. Second, this paper provides precise estimates on the contributions of minimum tillage to smallholder farmer welfare. This will contribute to the existing knowledge that farmers’ practices are context specific and the benefits of minimum tillage vary geographically.

We follow the estimation approach of [14] to assess the impact of adoption of agricultural technologies on farmers’ welfare. Our impact estimation, however, differs from that study by using household per capita net crop income and labor demand. Still, our study incorporated the effect of personal values in the study of adoption. This is contrary to [6], who captured the impact on household food security as a proxy to welfare, whereas we measured the total crop income per household.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Variable Description

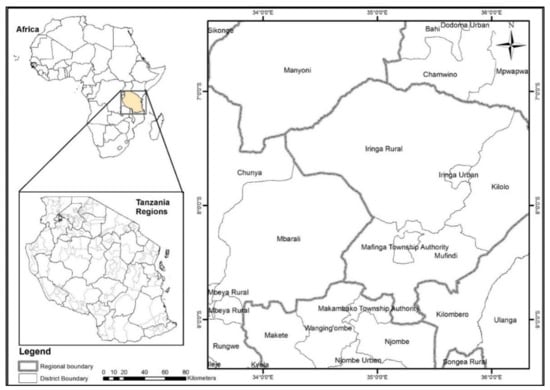

The dataset used in this paper was collected through a field survey in the southern agricultural corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT), where 75% of the total cultivated horticultural crops are produced. Iringa and Mbeya are two relatively homogenous regions in agricultural land use, ecological conditions and production practices. Kilolo and Mbarali districts from Iringa and Mbeya regions respectively were selected for this study because of their level of horticultural production and MT practice. Despite their high agricultural potential, smallholder farmers in the two districts suffer from low productivity, low levels of investments, increased effects of climate change and high rates of poverty. Besides, about 75% of the population depends directly on agriculture. Hence, this study area contains about 2 million hectares of small-scale farming, and the smallholder farmers mainly engage in mixed farming methods. Kilolo and Mbarali districts are male dominated, with 94.6% and 71.8% of the population staying in the rural areas, respectively. Nonetheless, Mbarali has a larger surface area, 24,439 km2 compared to Kilolo, 9244 km2. Maize, rice, and horticultural crops are the main crops farmed in these two districts. We used a cross-sectional research design to capture the overall picture of household welfare at a particular time. However, in this specific study, we focused on the horticultural crop farmers to assess the impacts of minimum tillage on their welfare because they form the largest group of farmers.

We evaluated two outcomes: productivity (income) and labor (total labor demand) in this paper. Further, we classified the exogenous variables into household characteristics, institutional factors, household wealth, climate change characteristics, and farm characteristics. The household characteristics comprise household size, gender, age, farming experience, literacy level, and years of residence of the household head. The institutional factors consist of access to extension services, farmer organization, water use groups, NGO information, and credit facilities. Household wealth includes an asset index and farm characteristics contain farmland size. Climate shock characteristics comprise the experience of a flood, the experience of drought, and future climate change.

We calculated the total revenue as a product of total production (kg) and the price received by the farmer. We then summed the income from all the plots per household to obtain total household revenue. Further, we estimated the total cost of production per plot using the variable costs. We then summed up all the costs associated with every plot to determine the total household cost of production. We calculated the difference between the total household revenue and total cost of production to get net crop income. We further divided the net crop income by the household size to get per capita net crop income.

2.2. Sampling

The initial stage of sampling consisted of purposive selection of the two districts, Kilolo and Mbarali. The second stage of sampling encompassed using the random number generator in Excel to create a full list of all the wards and randomly choosing 50% of them to participate in the study. This resulted in 11 and 10 wards from Kilolo and Mbarali, respectively. Further, based on the desired total sample for the ward, 19 and 21 villages in Mbarali and Kilolo were randomly selected. Additionally, a proportionate random sampling approach was employed to select 608 smallholder horticultural crop farmers. This dataset was collected by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in 2015–2016 with the main aim of evaluating intra-household decision-making and smallholder agricultural productivity. Before the study questionnaire was administered, a pretest was conducted in Magulilwa ward based on its size to identify potential problems and to prevent biases. The ambiguous questions were corrected and refined to bring clarity. The questionnaire was detailed to capture all the essential indicators and variables. Significantly, it contained information concerning the labor requirement characteristics, household characteristics, farm characteristics, farming practices, institutional factors, food security, as well as climatic shock characteristics. Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the area of study.

Figure 1.

A map showing the study area.

2.3. Empirical Model Specification

In this paper, the data analysis was conducted at the household level to ascertain the impacts on the farmers’ welfare. The various household-level variables were included in the empirical analysis. Conducting impact assessment using cross-sectional data is usually prone to selection bias [14,15]. Further, because of some unobserved characteristics, farmers using minimum tillage practice can self-select, leading to biases. The household head decisions are influenced by a host of factors that might be correlated with the outcome variables [16]. To solve this, Jena [17] suggested propensity score matching (PSM). In this study, we have used PSM, and it follows two steps. The first step entails selecting a probit regression model to ascertain the factors influencing the farmer’s decision to use minimum tillage [17]. The advantage of using a probit model is that it describes if households adopt minimum tillage (y = 1) with probability, q, or if the contrary (y = 0) with probability (y = 1 − q). The binary probit model was specified as:

where β is the model parameter, Xi is explanatory variables, and Ꜫi is the error term assumed to have a random distribution, zero mean, and common variance [18]. The probit model provides propensity scores [19]. Further, the matched clusters of adopters and non-adopters’ observations are generated and matched using different matching algorithms such as kernel matching, radius based matching, and nearest-neighbor matching approach. Therefore, for each household, there are two possibilities; practicing minimum tillage or not. We denote adopters as Ai (1) and non-adopters as Ai (0), whereby the impact of practicing minimum tillage is the difference in outcome between the clusters (Δ = A1 − A0). It is estimated and tested using a t-test for difference in mean values. Further, we specified the average treatment effect as

Ii* = βXi + Ꜫi

1 if Ii* > 0 and 0 otherwise.

ATT = E (Δ│X, D = 1) = E (A1 − A0│X, D = 1) = E (A1│X, D = 1) − E (A0│X, D = 1)

However, because E (A0│ D = 1) is not observed directly, a counterfactual of it should be generated. That is, the outcome the respondents would have attained had they not participated. Additionally, the matching is based on the common support area specified as

0 < Prob {D = 1|X = x} < 1 for x Ω X.

This matching guarantees the similarity of the matched pairs based on all the observable variables. The only difference is that the treated group has adopted, and the control group has not adopted minimum tillage [20]. PSM is criticiszed s for not accounting for the unobservable variables during estimation [21], and to cater for this, we estimated sensitivity analysis as recommended by Rosenbaum [22]. The results are presented in three distinctive sections, that is, descriptive statistics, factors influencing the adoption of minimum tillage, and the impacts this farming method has on per capita net crop income and labor demands.

3. Results

3.1. Household Characteristics

Minimum tillage was practiced in 130 households, representing 21.38% of the total sample size. A majority of the households were male headed with an average age of 48.5 years. Almost half of the household heads, 56.7%, had access to post-primary education and each household had about five family members on average. Further, on average, every household owned about 2.3 ha of farmland. In terms of assets ownership index, the minimum tillage adopters had a higher mean on average. Further, the adopting households had farming experience of 24.51 years on average, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the household characteristics.

Additionally, in terms of labor demand, man-days per hectare were lower in minimum tillage adopters compared to the non-adopters. This means that minimum tillage saves farming labor, a result synonymous with [23]. In terms of household head gender implications, this research could not prove whether minimum tillage saves women work, because they are known to offer family labor, since we determined the total household labor demand [24]. Nonetheless, the minimum tillage adopters used less labor during the land preparation, weeding, and harvesting periods as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Household labor demands by tillage.

3.2. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Minimum Tillage

The probit regression model results highlighted the factors influencing the adoption of minimum tillage in Southern Tanzania. The results, shown in Table 3, illustrate that gender of the household head, asset index, personal values, drought experience, farmer organization, and NGO information influenced a farmer’s decision to adopt minimum tillage.

Table 3.

Probit analysis results on the adoption of MT by households.

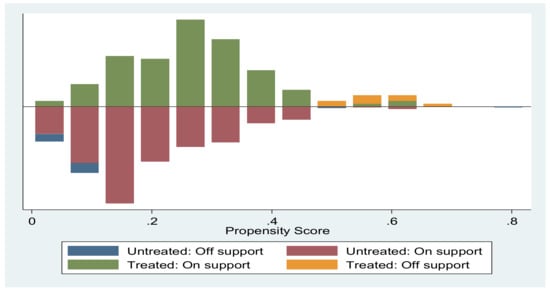

3.3. Impact of Minimum Tillage Farming on Per Capita Net Crop Income and Labor Demand

In this section, we present an estimation of the treatment effects based on propensity score matching (PSM). As a requirement, we used similar observable variables in the first-step probit regression model as in treated and control groups. We conducted a balancing test to ascertain this condition. Table 4 illustrates the observable variables’ mean comparison test between the adopters and the non-adopters before and after matching. Further, both the mean and median bias were reduced substantially after matching, explaining the importance of estimation balance power. There were no significant differences in the values of the minimum tillage adopters and the conventional tillage adopters as indicated by the reduced and insignificant pseudo-R2 after matching. Further, the reduction in mean and median bias, as well as insignificant p-value of the likelihood ratio, justified the choice of PSM in this paper.

Table 4.

Balancing test of observable variables in propensity score matching (PSM).

Figure 2 represents the common support test graph. After matching, most of the households used to estimate the average treatment effect were observed to be on the common support.

Figure 2.

Common support test.

Table 5 illustrates the PSM algorithms on the average treatment effects (ATT). In this study, we employed three matching algorithms; that is, the nearest neighbor method (NNM), kernel-based method (KBM), and radius matching method (RM). All these matching algorithms found that the change in per capita net crop income was statistically significant among the adopters. Further, we assessed the impact of minimum tillage on the total household labor demand. The result indicated that minimum tillage reduces the total household labor demand by 15.1754 man-days per ha. The model (PSM) indicated that minimum tillage adopters employed significantly less labor per man-days compared to their counterparts, non-adopters.

Table 5.

Average treatment effect of MT on per capita net crop income and labor demands.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

Researchers have observed the essentials of testing the reliability of the PSM model estimates [17,22]. Thus, we statistically determined the Rosenbaum bounds sensitivity analysis and presented the outcome in Table 6. The significant levels in the sensitivity result are not affected even after increasing gamma values by threefold. Therefore, we concluded that no external deviations could change the estimated values of ATT.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis results.

4. Discussion

From Table 3, gender of the household head affects the adoption of minimum tillage since the household head assumes the decision-making role. For instance, when a unit increased in male headed households, the adoption of minimum tillage increased by 13.65%. Men usually have more access to necessary factors of production compared to women as a result of sociocultural norms [25]. This study is in agreement with [26,27], which concluded that male-headed households were more likely to adopt agricultural practices compared to their female counterparts. Further, a unit increase in an asset index influenced the adoption by 1.9%. This explains the fact that asset ownership boosts the farmer’s decision-making in terms of resources availability. Farmers who have access to a variety of resources are deemed to make bold decisions when it comes to minimum tillage adoption.

Further, training farmers on personal values was found to be significantly associated with the adoption of the minimum tillage. This is because farmers tend to adopt the agricultural practices that accord them maximum satisfaction. Training on personal values influenced the adoption of minimum tillage by 14.29%. Moreover, farmers seem to understand the essence of minimum tillage especially during dry spells. This is because the farmers who had experienced drought adopted the minimum tillage practice. In essence, a farmer experiencing drought during the farming season influenced the uptake of minimum tillage by 8.9%. We reasoned that minimum tillage practice provided them with food security in the case of unpredictable rainfall. This finding supports the conclusion of [28] that documented that drought experience influences farmers to adopt adaptive measures.

The vital question of this research was whether minimum tillage improves household per capita net crop income and reduces household labor demand, and the results observe an improvement effect. Reduction in the labor demand in terms of female labor is considered an essential welfare improving effect. This is because the world over, women are the more disadvantaged group, creating a gender disparity in developing economies [27]. This is critical in farming because women offer a higher proportion of labor than men. Why is this so? [32] noted that minimum tillage significantly saves on labor demand, and [33] observed that minimum tillage enhances the household income in the long run, while [34] indicated that minimum tillage improves crop yield and incomes of smallholder farmers. Further, the informal interviews with the focus groups and farmers highlighted the fact that minimum tillage farming awareness and knowledge is scarce among most of the farmers, which means that serious efforts have not been offered to adopt and practice minimum tillage in the southern areas of Tanzania. Even more, the findings proposed that minimum tillage could profoundly improve farmers’ welfare if it is supported by better agricultural practices such as clearing farms, planting, weeding, and harvesting at the right time. We also observed that not much effort had been provided to practice minimum tillage in Southern Tanzania. This is supported by [35], who noted that global cropland under conservation agriculture was only 9% in 2012, and the most significant percentage of this was in South America. There is little or no success in conservation agriculture in South Asia and Africa [36]. Besides, there are a lot of challenges that affect smallholder farmers when they adapt and adopt agricultural conservation practices in Africa [37]. Additionally, Ref. [38] advocated for the identification of scenarios where minimum tillage can enhance the smallholder farmers’ welfare intensely and [39] proposed several series of research to ascertain the minimum tillage approaches.

From the institutional factors, farmers who were members of different farming organizations adopted minimum tillage. However, it influenced the adoption negatively because, in as much as farmers share new information among themselves, learning externalities can cause antagonistic effects due to free-riding behavior particularly when the group is large. Most farmers tend to experiment with others before they decide to adopt a particular practice [29]. Similarly, farmers who had access to non-governmental organization (NGO) information adopted the minimum tillage practices. We reasoned that NGOs provide both information and resources necessary to influence the adoption of any agricultural practice [30]. Nevertheless, household head age, years of residence, household size, and literacy index did not affect the adoption of minimum tillage. Moreover, future climatic changes, government extension, agricultural group membership, water user group membership, access to credit, farming experience as well as arable land did not significantly influence a household’s decision to adopt minimum tillage. These results are similar to the findings of [31].

Further, from the PSM algorithm results, we reasoned that the adoption and success of minimum tillage are context-specific, considering the socioecological and agronomic factors. We observed that the positive effects of minimum tillage adoption take place in the context of complementary inputs and hence, lowering the costs of these inputs can assist farmers in trying out new farming practices such as minimum tillage. Similarly, investing in agricultural mechanization systems can enable smallholder households to expand their land under minimum tillage, thus improving their welfare in terms of crop income and saving labor demand. While this paper offers significant evidence of the relevant essential policy variables for green agricultural development, we recognize a handful of limitations. First, we do not know the period the smallholder households have been practicing minimum tillage, and the results are based on the cross-sectional data. Hence the results can be translated as short-term impacts, and in this paper, we draw results from a small sample of the households and do not, therefore, offer a national picture. However, widely applying the results of this paper can enhance the welfare of the smallholder farmers in Tanzania.

5. Conclusions

From the results obtained in this paper, despite the increased promotion of conservation agriculture, specifically minimum tillage, smallholder farmers are still uncertain about its profitability in Southern Tanzania. Further, we assessed the impacts of adopting minimum tillage on smallholder households’ welfare using per capita net crop income and total labor demand. We used probit regression to ascertain factors influencing the adoption of minimum tillage in Southern Tanzania. We found that gender of the household head, asset index, training on personal values, the experience of drought, access to non-governmental information, and farmer organization membership influence the household’s decision to adopt minimum tillage.

Similarly, we observed from the three PSM algorithms, nearest neighbor method, kernel-based method, and radius method that adoption of minimum tillage positively and significantly impacts household per capita net crop income with t-values ranging between 2.14 and 2.24. It also reduces the total household labor demand significantly with the t-values ranging between 2.91 and 5.65. This has more significant implications for both the smallholder farmers and researchers because reduction in labor demand would allow the households to engage in other income-generating activities in Sub-Saharan Africa (Tanzania). Further, supporting households to use complementary farm inputs such as inorganic fertilizers, access to credit facilities, as well as access to minimum tillage extension-specific information could improve the adoption intensity and welfare benefits. We also recommend the improvement of this research that could consist of randomized controlled trials and economic field experiment data collection methods to determine the impact on the adoption of minimum tillage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O. and A.L.; methodology, M.O.; software, M.O.; validation, M.O., A.L. and C.M.M.; formal analysis, M.O.; investigation, A.L.; resources, M.O.; data curation, M.O. and C.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.; writing—review and editing, A.L. and C.M.M.; visualization, C.M.M.; supervision, A.L.; project administration, M.O.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the research fund sponsorship by Jiangsu Social Science Association Project, grant number 20SCB-05, International Cooperation Project of Nanjing Agricultural University, grant number 2018-EU-18, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number KYYJ202010 and SKYC202002, Social Science Foundation for Universities in Jiangsu, China, grant number 2017ZDIXM096, Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions Project (PAPD) and Cyrus Tang Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are also grateful to the International Center of Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) for sharing their data on the Harvard dataverse (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/CIAT) for public consumption. We utilized part of these data in our study. We also thank Timothy Njagi, from Tegemeo Institute of Agricultural Policy and Development and Research, Egerton University, Kenya, for his comments and contributions that helped to improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brown, B.; Llewellyn, R.; Nuberg, I. Global learnings to inform the local adaptation of conservation agriculture in Eastern and Southern Africa. Glob. Food Sec. 2018, 17, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Nuberg, I.; Llewellyn, R. Negative evaluation of conservation agriculture: Perspectives from African smallholder farmers. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 15, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conyers, M.; Van de Rijt, V.; Oates, A.; Poile, G.; Kirkegaard, J.; Kirkby, C. The strategic use of minimum tillage within conservation agriculture in southern New South Wales, Australia. Soil Till. Res. 2019, 193, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apesteguía, M.; Virto, I.; Orcaray, L.; Bescansa, P.; Enrique, A.; Imaz, M.J.; Karlen, D.L. Tillage Effects on Soil Quality after Three Years of Irrigation in Northern Spain. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astatke, A.; Jabbar, M.; Tanner, D. Participatory conservation tillage research: An experience with minimum tillage on an Ethiopian highland Vertisol. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 95, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, K.; Faße, A.; Grote, U. Implications of climate-smart strategy adoption by farm households for food security in Tanzania. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, J.; Kessler, A.; Nibbering, J.W. Agriculture and food security in selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa: Diversity in trends and opportunities. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derpsch, R.; Lange, D.; Birbaumer, G.; Moriya, K. Why do medium- and large-scale farmers succeed practising CA, and small-scale farmers often do not?—Experiences from Paraguay. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2016, 14, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O. Crop residue mulching in tropical and semi-tropical countries: An evaluation of residue availability and other technological implications. Soil Till. Res. 2002, 67, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Holden, S.T.; Thierfelder, C.; Katengeza, S.P. Awareness and adoption of conservation agriculture in Malawi: What difference can farmer-to-farmer extension make? Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Corbeels, M.; Nyamangara, J.; Triomphe, B.; Affholder, F.; Scopel, E.; Tittonell, P.A. A research agenda to explore the role of conservation agriculture in African smallholder farming systems. Field Crops Res. 2011, 124, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Witter, E.; Corbeels, M.; Tittonell, P.A. Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: The heretics’ view. Field Crops Res. 2009, 114, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, P.P.; Kerr, J.; Haggblade, S.; Kabwe, S. Determinants of adoption and disadoption of minimum tillage by cotton farmers in eastern Zambia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 231, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Chang, C.; Larney, F.J.; Nitschelm, J.; Regitnig, P. Effect of minimum tillage and crop sequence on crop yield and quality under irrigation in a southern Alberta clay loam soil. Soil Till. Res. 2001, 59, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.A.; Ali, A.; Ashfaq, M.; Hassan, S.; Culas, R.; Ma, C. Impact of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Practices on Cotton Production and Livelihood of Farmers in Punjab, Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaka, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Asenso, E.; Li, J.H.; Li, Y.T.; Wang, J.J. Sustainable Conservation Tillage Improves Soil Nutrients and Reduces Nitrogen and Phosphorous Losses in Maize Farmland in Southern China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, P.R.; Stellmacher, T.; Grote, U. Can coffee certification schemes increase incomes of smallholder farmers? Evidence from Jinotega, Nicaragua. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T.; Derpsch, R. Global spread of Conservation Agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 76, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T.; Shaxson, F.; Pretty, J. The spread of Conservation Agriculture: Justification, sustainability and uptake. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2009, 7, 292–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiboi, M.N.; Ngetich, K.F.; Diels, J.; Mucheru-Muna, M.; Mugwe, J.; Mugendi, D. Minimum tillage, tied ridging and mulching for better maize yield and yield stability in the Central Highlands of Kenya. Soil Till. Res. 2017, 170, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowler, D.; Bradshaw, B. Farmers’ adoption of conservation agriculture: A review and synthesis of recent research. Food Policy 2007, 32, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaweesa, S.; Mkomwa, S.; Loiskandl, W. Adoption of Conservation Agriculture in Uganda: A Case Study of the Lango Subregion. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarek, A.M. Conservation agriculture in western China increases productivity and profits without decreasing resilience. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmar, R. Adoption of conservation agriculture in Europe: Lessons of the KASSA project. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madarász, B.; Juhos, K.; Ruszkiczay-Rudiger, Z.; Benke, S.; Jakab, G.; Szalai, Z. Conservation tillage vs conventional tillage: Long-term effects on yields in continental, sub-humid Central Europe, Hungary. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2016, 14, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.W.; Hanks, J. Economic analysis of no-tillage and minimum tillage cotton-corn rotations in the Mississippi Delta. Soil Till. Res. 2009, 102, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, B.W.; Menale, K.; Diiro, G.; Muricho, G. Does gender matter in the adoption of push-pull pest management and other sustainable agricultural practices? Evidence from Western Kenya. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Thavhana, M.; Randela, M.; Mokoena, L. Barriers Affecting Sustainable Agricultural Productivity of Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndah, H.T.; Schuler, J.; Diehl, K.; Bateki, C.; Sieber, S.; Knierim, A. From dogmatic views on conservation agriculture adoption in Zambia towards adapting to context. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoli, A.; Baudron, F.; Sida, T.S.; Schut, A.G.T.; van Heerwaarden, J.; Giller, K.E. Conservation agriculture with trees amplifies negative effects of reduced tillage on maize performance in East Africa. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, H.; Mason, N.M.; Sitko, N.J. Does minimum tillage with planting basins or ripping raise maize yields? Meso-panel data evidence from Zambia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 212, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R.S.; Corbeels, M. The farm-level economics of conservation agriculture for resource-poor farmers. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 187, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedzisa, T.; Rugube, L.; Winter-Nelson, A.; Baylis, K.; Mazvimavi, K. The Intensity of adoption of Conservation agriculture by smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Agrekon 2015, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Zambrana, E.; Fite, R.; Sole, A.; Tenorio, J.L.; Benavente, E. Yield and Quality Performance of Traditional and Improved Bread and Durum Wheat Varieties under Two Conservation Tillage Systems. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Smith, J.P.; Stirling, G.R. Integration of minimum tillage, crop rotation and organic amendments into a ginger farming system: Impacts on yield and soilborne diseases. Soil Till. Res. 2011, 114, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, C.M.; Swanepoel, L.H.; Smith, H.J. A review of conservation agriculture research in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil. 2018, 35, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, C.; Chivenge, P.; Mupangwa, W.; Rosenstock, T.S.; Lamanna, C.; Eyre, J.X. How climate-smart is conservation agriculture (CA)?—Its potential to deliver on adaptation, mitigation and productivity on smallholder farms in southern Africa. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, C.; Mutenje, M.; Mujeyi, A.; Mupangwa, W. Where is the limit? Lessons learned from long-term conservation agriculture research in Zimuto Communal Area, Zimbabwe. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesah, F.M.; Mutua, E.N.; Izugbara, C.O. Gender and conservation agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2019, 17, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).