2. The Sanctuary Site of Agia Irini: Context, Cult and Iconography

The extra-urban sanctuary of Agia Irini may be associated with the transformed political geography of the Early Iron Age [

5,

6]; this extra-urban sanctuary has usually been regarded as the ‘classic’ rural Iron Age Cypriot sanctuary but there are well-founded reservations about how ‘rural’ the site was in the minds of the ancient people connected with it [

6], [

7] (pp. 300–301), [

8]. The site constitutes a uniquely preserved (or excavated) example of an Iron Age

temenos, since the votive objects were found in a primary context, many of them in situ, facing an altar and placed at different heights ([

9] (pp. 642–824) (for new readings of the stratigraphy, see [

10] (pp. 151–153), [

11,

12]). The flooding phenomenon at Agia Irini seems to have had an impact on the sanctuary’s layers. The present study has considered the preliminary results presented in recent publications [

11,

12,

13].

According to Webb’s interpretation, most of the Agia Irini Bronze Age architecture was purely secular: while the identification of the central unit, consisting of a small two-roomed building on the same orientation as the courtyard with a hall to the southeast (Room V) and a small inner room (Room VI) to the northwest has been widely accepted, the nature of the surrounding buildings is far from clear and, as she convincingly argued, these belong to a Late Bronze Age settlement [

14] (p. 57). Traditionally, in accordance with the Swedish Cyprus Expedition’s suggested chronology, destruction is recorded within the Late Bronze Age but in the early Cypro-Geometric period the place acquires a clearly religious function.

In the Cypro-Geometric period a

temenos was constructed, which—according to the excavators and some later scholars following this interpretation—experienced no interruption in cult activity until the late 6th century BC [

15], [

16] (pp. 67–68), [

17] (p. 100) (cf. [

11], [

12] (pp. 151–156)) (see below). This second phase of the sanctuary has been dated from the Cypro-Geometric I to the Cypro-Geometric III period. Fourrier has recently challenged the unbroken continuity from the Late Cypriot to the Iron Age based on a careful stylistic analysis of the material [

18] (pp. 104–106) (cf. [

11] (p. 38), [

19] (p. 151)). She suggests that the sanctuary was abandoned in the Late Bronze Age and only reoccupied in the Cypro-Geometric III period.

The unbroken sequence at Agia Irini between the Late Bronze and the Early Iron Age is further undermined by the stratigraphic discrepancies of the site that provide no firm confirmation of a continuous use during the aforementioned period, as well as by the comparatively lower archaeological visibility of the hypothesised early Cypro-Geometric phase [

13] (pp. 92–96). Pottery evidence in particular seems to confirm that although the site was attended in the Cypro-Geometric I–II period, it is from the Cypro-Geometric III onwards that activity at Agia Irini reached unprecedented levels (see below). If the sanctuary was reinvigorated in the Cypro-Geometric III period as fresh studies seem to suggest, then this development is particularly important. It would place Agia Irini in line with the establishment of other extra-urban sanctuaries with

temene during this period and the probable memorial patterns related to political and territorial competition by the emerging polities of the Iron Age [

6,

7]. In other words, the late Cypro-Geometric foundation horizon of a real

temenos may be related to the consolidation and re-organisation of the city-kingdom polities and their territories and the shift, in which sanctuaries had a major role, from a more private to a more public display of power [

7] (pp. 304–307). The appearance of clearly palatial structures, large-scale sculpture, monumental built tombs and regional styles across the whole of the Cypriot landscape, as well as the proliferation of the Cypro-syllabic script, are manifestations of these changes.

The apogee of the sanctuary in votive offerings dates to the late Cypro-Geometric and Cypro-Archaic periods with a short revival in the Hellenistic period [

11] (pp. 39–41,43), [

12] (p. 153), [

16] (p. 68), that is, to the consolidation of the Cypriot polities. Evidence related to cultic activity, such as bull terracotta statuettes, do occur in Cypro-Geometric I [

10] (pp. 157–160, nos. 181–184) but numbers of these votive offerings are significantly less than those of the Cypro-Geometric III and Cypro-Archaic periods. The new role of the sanctuary within this competitive and formative political setting of Early Iron Age Cyprus is clearly manifested also through the scale and iconography of many of its terracotta statues. The large-scale terracotta statues of Agia Irini would have looked imposing in the landscape due to their size and austere virile appearance and must have served a special purpose, not just as expensive votive offerings but also as awe-inspiring symbols of power and control (

Figure 2), a point further explored later in this article. Noticeably, the largest statue wears a turban-like headdress that according to Herodotus (VII: 90) was worn by Cypriot kings (

basileis) (

Figure 3) [

10] (p. 184, no. 211), [

12] (p. 111).

This differentiation between Iron Age Agia Irini and its Bronze predecessor is reflected also in the architectural layout of the sanctuary (for an architectural synthesis of the Agia Irini see [

9] (pp. 666–674) and [

11] (p. 40, table 2)). In the Cypro-Geometric III period, the Late Cypriot remains were levelled and a typical—yet modest—Iron Age sanctuary in the form of an open-air

temenos was built. Its main features were a large roughly-built

peribolos and an altar. These new elements, dated to the 9th century BC, marked the architectural remodelling of the sanctuary in the Iron Age [

9] (pp. 671–674), [

10] (pp. 152–153), [

11] (p. 40). Secondary architectural features also characterise Iron Age Agia Irini but their precise function and dimensions are usually difficult to discern in the publication. Good examples of such elements are the poorly preserved semi-circular stone pavements (substructures 48A and 48B in the original publication) [

9] (p. 651) that were viewed as puzzling by Sjöqvist and Gjerstad. These ‘substructures’ were recently interpreted as parts of circular stone pavements or platforms that served cultic purposes during the Geometric and Archaic periods, based on finds—votive figurines and pottery fragments—and on comparanda from other Cypriot and Aegean sites [

12] (pp. 109–111). Furthermore, Gjerstad had interpreted a triangular area built of rubble in two or three courses as a low altar (Altar 49) that he associated with Agia Irini Period 2, dated between Cypro-Geometric I and the middle of Cypro-Geometric III period [

9] (pp. 651, 671, 817). This rubble-built structure was recently viewed as belonging to a much larger stone pavement of cultic character like the ones mentioned previously, based on the examination of Lindros’ draft stone-by-stone plan, a modified version of which was included in the 1935 publication of the sanctuary [

12] (p. 109, figure 1). However, this interpretation remains elusive since it receives no sound confirmation from the archaeological record. A new altar of the Iron Age sanctuary (Altar 50) was erected in Period 3 and remained in use until the end of Period 6. This new structure that replaced the old rubble altar consisted of a monolithic limestone block with a square and well-dressed upper part. It was founded on a sterile levelling layer of rubble, on the rock [

9] (pp. 662–663 (section XVII), 671). The construction of Altar 50 was therefore associated with the earliest part of Agia Irini Period 3, dated to the middle of Cypro-Geometric III period on the basis of pottery sherds the majority of which belonged to pottery of Type III [

9] (pp. 817–818), [

12] (pp. 112–113). Given that altars form indispensable elements of cultic activity, the construction of the first securely-attributed altar at Agia Irini in the Cypro-Geometric III adds further support to the reoccupation of the sanctuary in this period. The Cypro-Geometric III altar was associated with a stone interpreted as a

baetyl, that is, an aniconic stone cult statue of the deity.

Evidence suggests that the sanctuary functioned for a relatively short period in comparison with other sanctuaries. However, the chronological designation of the abandonment of Agia Irini is still debated. The excavators had dated the end of the final phase of the sanctuary (Period 6) to ca. 510–500 BC, based on the comparisons with pottery finds outside Wall 3 at Idalion and on the absence from Agia Irini of the latest Cypro-Archaic II pottery types [

9] (p. 818). Such a chronology, followed also by other scholars [

10] (p. 153), would also befit the political upheavals that followed the Persian conquest of Cyprus in 525 BC and the subsequent attempt of certain Cypriot kings towards the end of the 6th century to act against the Achaemenid dominance [

8]. Fourrier suggested a slightly earlier date, around the middle of Cypro-Archaic II, based on a somewhat similar argument, the absence from Agia Irini of the Solian terracotta production of the final Cypro-Archaic and beginning of the Cypro-Classical period [

18] (pp. 88–90). While the reasons behind the abandonment of the sanctuary are still not fully understood, its relatively short-life offers an advantage for us as archaeologists, as we can better grasp the function of the sanctuary in a specific chronological era.

As manifested above, based on the existing published evidence, the Cypro-Geometric I–III phase of the sanctuary is problematic. The majority of the ex-votos with a date in Cypro-Geometric III period consist of terracotta bulls, which originally were placed around the altar. Other votive offerings probably belonging to this phase consist of animal and ‘minotaur’ statuettes and human figures. Some of the bulls and ‘minotaurs’ dating between the Cypro-Geometric III and Cypro-Archaic I periods have snakes writhing along the neck and back [

9] (plates CCXXIV–CCXXVIII), [

10] (pp. 157–166). The ‘minotaur’ statuettes have their arms uplifted (

Figure 4), a gesture clearly related to the cult of the ‘Cypriot Goddess’ [

20] (pp. 67–70), [

21]. A Cypro-Archaic ‘minotaur’ figurine reveals even more ‘hybrid’ features: A cylindrical human torso with male genitalia, female breasts and animal legs [

9] (plate CCXXVIII.4), [

10] (pp. 164–166 no. 190), probably alluding to a dual-sexed image [

6] (p. 80). A two-headed Cypro-Archaic terracotta figure wearing a helmet from Agia Irini might also be a personification of such a dual, ambivalent identity [

9] (plate CCXXXIII.9).

Similar questions about the Early Iron Age evidence from Agia Irini arise also when looking at the published pottery from the site. Leaving aside Agia Irini Period 1 that corresponds to the Late Bronze Age use of the site, Periods 2 to 6 were thought to mark the continuous use of the sanctuary from ca. 1050 to 500 BC [

11] (pp. 41–42). Periods 2 and 3 were ascribed a Cypro-Geometric chronology, whereas Periods 4, 5 and 6 fall entirely in the Cypro-Archaic period. As discussed above, the idea of the uninterrupted use of Agia Irini from the Late Bronze to the Early Iron Age has been scrutinised on more than one occasion [

13] (pp. 92–95), [

18] (p. 89), especially with regard to the chronology of Period 2 (ca. 1050–800 BC) upon which the theory of a Cypro-Geometric I use of Agia Irini was based. A closer look at the published pottery associated with Period 2 demonstrates that the only complete vase and 33.5% (80 out of 238) of pottery sherds from this period actually belong to Cypro-Geometric III types, with 158 sherds dated to Cypro-Geometric I–II periods [

9] (pp. 812, 817). The presence of Cypro-Geometric I–II sherds was confirmed also during the study of the unpublished pottery from the site at the Medelhavsmuseet in Stockholm, as part of a postdoctoral research project. However, their numbers were relatively low and they were always found intermixed with later material, since no exclusively Cypro-Geometric I–II layer could be verified. This fact, viewed alongside the extensive architectural remodelling of the site in the Cypro-Geometric III period, seems to support that official cultic activity at Agia Irini was re-established in the course of Cypro-Geometric III period. Agia Irini Period 3 (ca. 800–700 BC), to which the first securely identified altar belongs, comprised two vessels, one dated to Cypro-Geometric III and the other to Cypro-Archaic I, whereas 58.5% of the pottery sherds associated with Period 3 (167 out of 287 sherds) belonged to type III (Cypro-Geometric III), followed by 16.7% (48 out of 287 sherds) that belonged to Type IV (Cypro-Archaic I). The comparative look at pottery from these two periods (Period 2 and 3) that mark the Cypro-Geometric use of the sanctuary, clearly point to the dominant position of Cypro-Geometric III pottery types and seem to further support the idea of the sanctuary’s firm re-establishment in the Cypro-Geometric III rather than Cypro-Geometric I period. Evidence dated prior to Cypro-Geometric III period does exist but it may actually correspond to more occasional or less frequent cultic visits to the sanctuary.

In Period 4 (ca. 700–600 BC) that roughly coincides with Cypro-Archaic I, the sanctuary was enlarged by widening the

peribolos wall around the

temenos. Cult continued uninterrupted from Period 3 although votive offerings reached their peak during the Cypro-Archaic I period. Nonetheless, certain aspects of the cultic practices may be deduced with a fair amount of confidence based on the iconography of the votive offerings. For example, we may assume that bulls’ masks were worn during the ceremonies as part of ritual dress. Among other finds, two separate (i.e., not part of a group composition like the case of Kourion discussed below) figures putting on a bull-mask are preserved (

Figure 5); similar gestures in figurines have been found both in the sanctuary of Apollo Hylates at Kourion, in the necropolis of Amathous, the extra-urban sanctuary of Athienou-Malloura and so forth. ([

9] (plate CCXXXIII.8), [

10] (pp. 162–163, no. 187), [

22]; for a full catalogue of masked figures see [

23] (pp. 27–39)). Other aspects of the Iron Age ritual can also be postulated based on the archaeological data from the sanctuary. It almost certainly involved food and drink consumption in the form of sacred banquets, as is evidenced through the pottery shapes and the amounts of animal bones, mostly sheep and goat, retrieved during excavation. In addition, ritual circular dances were taking place at Agia Irini, a fact further confirmed by the presence of votive figurines that portray flute and tambourine players or ring dancers (

Figure 6) [

10] (pp. 151, 198–199, no. 228), [

11] (pp. 37, 43). Apparently, Late Cypriot religious practices seen, for example, at Kition and Enkomi survived into the mature Early Iron Age and continued into the Cypro-Archaic period.

Most of the Cypro-Archaic ex-votos at Agia Irini consist of terracotta human sculptures of various sizes, from small to life-size statues, figures of warriors and chariots [

10] (pp. 168–198), [

24,

25]. In spite of the amount of votive offerings, details of the cult at Agia Irini remain unknown due to the absence of textual evidence, although the deity worshipped probably had functions and roles that exceed those merely concerning fertility (cf. [

10] (p. 152)). The assumption that the sanctuary at Agia Irini was dedicated to a male fertility god of agrarian nature might well be correct. While the presence of male iconography is a standard method of identifying the nature of the deity in Mediterranean sanctuaries, the sex of votives is not necessarily always connected with the sex of the deity [

26]. However, comparative evidence from other Iron Age Cypriot sanctuaries sheds more light on this question [

4] (p. 555).

In accordance with other Iron Age extra-urban sanctuaries of the island (such as Athienou-Malloura, Golgoi-Agios Photios, Lefkoniko, etc.), we should probably add more roles to the deity venerated at the site, related to the territorial formation of the Iron Age Cypriot polities. Instructive for the application of a methodology, which aims to recognise counterpart religious ideologies in the material culture of the Iron Age extra-urban Cypriot sanctuaries, is the study of Counts on the iconography of the ‘Master of the Animals’ encountered in many sanctuaries in the Mesaoria plain [

27] (with references). In addition, the display of large-scale votive statues in some of these sanctuaries should be seen within the ideological competition of the various city-kingdoms in ‘frontier zones’ to mark (at least symbolically) their power over their territories.

The well-documented votives of the Agia Irini sanctuary might be associated with a similar ideological construction present also on the north-western part of the island. The sanctuary provides a nexus of ideas, admittedly ‘dark,’ complex and impenetrable to

our eyes, that might link Late Cypriot and later city-kingdom religious traditions better than any other excavated site [

1] (p. 267), [

6]. A preliminary study of the iconographic elements from the sanctuary seems to identify a male Cypriot divinity with religious ideas related to the Cypriot so-called ‘Master of the Animals.’ Nonetheless, we are not yet in a position to argue that in Agia Irini we have the same male deity (deities) as that found in Mesaoria. The various representations of male gods in Cyprus may be viewed as visual manifestations of a ‘Great God’ who acted as consort to the island’s ‘Great Goddess’ [

27] (p. 140), [

28] (pp. 26–28, 216–218). Based on the lack of contemporary textual evidence and the convoluted Cypro-Archaic divine iconography, we are far from understanding whether we should speak of one ‘Great God’ or of more male deities with similar functions on the island during the Cypro-Archaic period. Counts, opposing the idea that the various types correspond to different local or foreign divinities, suggests that the various male deities should be associated with the conception of a single, principal male divinity associated with particular sanctuaries in the Mesaoria region [

27], with references). Even though the unification of many qualities in a single male deity worshiped throughout the island remains inconclusive, the presence of royal ideology in such extra-urban sanctuaries in association with one male deity (or more) has been implied in the archaeological literature. Yet, this subject needs further refinement [

1] (p. 267), [

27].

Both infantry and warriors in chariots in various sizes are represented in the Iron Age strata at Agia Irini. Such iconographic evidence is clearly related to the reception (and imitation) of elements of royal ideology by upper societal strata and probably by other non-elite groups in order to express a prevalent cosmological system. In addition, the presence of specific iconography (such as sphinxes, bull iconography or Egyptianising material), point to the manifestation of Cypriot city-kingdom royal power and ideology in the context of the sanctuary [

6] (pp. 81–84), thus contributing to its character as a central place. This was a place of display of elite ideology and negotiation of social identities. The presence of large-scale terracotta sculpture and of specific iconographic types in the sanctuary seems to have stressed a symbolic claim of domination over the territory.

3. Applying GIS and Landscape Archaeology

As we argue in this contribution, the combination of archaeological indicators and GIS analyses reinforce the argument that the Agia Irini sanctuary possessed an important hierarchical position in the political and economic life of the area. To better secure this observation, we examine the topographical setting of the sanctuary in a broader landscape perspective, considering its relation to the nearest settled environment and natural resources.

As we further discuss below, scholarship has viewed the sanctuary in a ‘frontier zone’ critical for the territorial formation of Lapithos and Soloi. Fourrier has attempted to organise Cypro-Archaic terracottas from various sanctuaries in a system based on artistic style, drawing specific patterns of diffusion within each region, the centre of which is assumed to have functioned as a capital of royal authority [

18] (p. 113, figure 9). She regards a regional style as a shared element of a community that can be defined through a consideration of morphological characteristics, manufacturing techniques and sources of influence. Fourrier proceeds to a discussion of the diffusion of the various styles in the sanctuaries attempting, where possible, a distribution based on the distance from the production centre: sanctuaries very close to the centre (

le cercle proche), territorial sanctuaries (

les sanctuaires de territoire) and frontier sanctuaries (

les sanctuaires de frontière) [

18]. She allocates many extra-urban sanctuaries in the territories of specific city-kingdoms, or in frontier zones between two city-kingdoms. In the Cypro-Archaic period, these sanctuaries should have belonged to secondary centres, villages and/or farmsteads within the sphere of influence of specific city-kingdoms. She, therefore, identifies liminal zones between the various city-kingdoms. According to Fourrier in most frontier sanctuaries we find material—mainly terracotta figurines and terracotta sculptures—belonging to more than one regional style. While several scholars have placed the sanctuary of Agia Irini within the territory of Lapithos (for bibliography see [

17] (p. 100) and [

20] (p. 378)), Fourrier, using stylistic criteria that in her opinion reflect politico-economic settings, assigns the sanctuary to the territory of Soloi [

18] (pp. 89–92).

It is true that the sanctuary of Agia Irini also produced terracotta statues and statuettes that have been associated with the production of Cypriot polities other than of Soloi. Most important among them are the imports from Kition. Fourrier identified two groups of terracottas at Agia Irini that were either of Kitian origin or produced under strong Kitian influence [

18] (p. 91). Almost of equal importance to the Kitian evidence are the imports from Idalion (or terracottas of Idalian style) which are not exclusive to Agia Irini but are also attested at other sanctuaries within the realm of Soloi such as at Meniko and Lefka [

18] (p. 91). Far less common is the occurrence at Agia Irini of the products form Amathous, Salamis and Paphos [

18] (pp. 91–92). In addition, Orsingher based on the evidence from funerary contexts at Agia Irini-Paleokastro, argued for a connection with Salamis, Amathous and primarily with Kition, a link further supported by Phoenician inscriptions, the iconography of a funerary stela and the aforementioned representation of Kitian terracottas at the sanctuary [

29]. Despite the extreme dearth of Phoenician-type pottery from the sanctuary [

13] (p. 100)—as opposed to the nearby necropoleis—cult at the sanctuary of Agia Irini has been repeatedly viewed through Phoenician spectacles [

12,

30], a fact that has been questioned in other occasions [

6] (pp. 83–84, 97–99).

The cultural unity of the city-kingdoms of Cyprus includes regional variability created by inter-regional influences and stylistic comparisons. We view stylistic influence

vis-à-vis with other aspects of material culture, epigraphic sources and topographical features, to further clarify the picture [

4,

31]. In addition, modern research on pottery further argues in favour of a more centralised production for each polity [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Taking altogether the evidence from Agia Irini we wish to re-think whether the sanctuary should be considered a ‘frontier’ or simply a ‘territorial’ sanctuary.

The digital data used for the GIS analyses derive from the Eratosthenes database, maintained by the Department of Geological Survey, the Department of Land and Surveys and the Department of Agriculture (soil and water use section) of the Republic of Cyprus. The data used for the analyses were the digital elevation model (DEM) of Cyprus, the geological map, ancient copper slags, rivers, village centres and the Cypriot landscape soil map. Agricultural soils are those suitable for cultivation. Nevertheless, agricultural areas with some sort of cultivation nowadays, thus possibly also in the past, are included. In addition to Iron Age urban centres, our maps also include all the known sanctuary sites in the broader region (

Table 2), digitised and maintained in the Unlocking Sacred Landscapes of Cyprus (UnSaLa-CY) database. For the purposes of this article we attempted three sets of GIS analyses, all run in commercial ArcGIS: Visibility Analysis (VSA), Cost Surface Analysis (CSA) and Least Cost Paths (LCP). However, we recognise that the use of these analyses in archaeology is complementary. We consider them only as supportive evidence for the boundaries suggested by archaeological evidence, rather than as analyses that in their own right indicate the existence of boundaries or liminal zones. What we suggest here is that we should abandon linear and simplistic approaches to the territorial formation of the Cypriot polities, adopting a more flexible and holistic approach that values the realities of the landscape and its resources and considers the totality of the available evidence. In this way, we hope to overcome the deterministic nature of GIS, while simultaneously avoiding explanations derived only from stylistic analyses and uncritical applications of computational models (for further explanation and analysis on the data and also methodological issues and problems behind these GIS analyses see [

4]).

The economic model that shaped the political geography of Iron Age Cyprus depended on the control of a unified territory that had access to copper sources, agricultural land and a coastal gateway [

5], [

6] (p. 75, with references). Our environmental maps clearly show that Agia Irini has no direct connection with the Cypriot pillow lavas and basal formations where copper was extracted from and that would have probably been an important topographic factor in the placing of Cypriot Iron Age sanctuaries [

4]. What our mapping shows however is that Agia Irini dominated the northern limit of the rich agricultural plain of Morphou (

Figure 7). Northeast of the sanctuary are the hilly westernmost offshoots of the Pentadactylos range.

The VSA from Agia Irini confirms that the sanctuary has no visibility towards Lapithos (

Figure 8). The northeast view is totally restricted by the presence of the Pentadactylos Mountains Range. Thus, it becomes clear that one should definitely consider the terrain when attempting to discuss whether the sanctuary belonged to the territory of Lapithos or Soloi. Agia Irini, however, has strong visibility towards the sea and, primarily, towards Soloi and its surrounding area including other sanctuaries in the region of Soloi, the agricultural land and the copper resources south of Soloi, where evidence of ancient copper slag heaps and workings have been identified [

37]. The visibility from Agia Irini across the Solian territory may correspond to the economic, political, or religious connections of the sanctuary. Thus, the visibility from the site, added to the archaeological evidence described above, supports placing the sanctuary primarily within Soloi’s sphere of interest. The VSA from Soloi also confirms the visual relation of this polity rather than of Lapithos with the sanctuary (

Figure 9). While Lapithos has total visibility towards the north cost of Cyprus but no visibility at all with Agia Irini, Soloi has visibility with the sanctuary and total visual control of the Morphou Bay and a very large part of the Morphou plain.

It is interesting to discuss here the visibility between Agia Irini and the other securely identified Cypro-Archaic sanctuaries in the broader region, namely with the coastal sanctuary at Soloi-Acropolis and those at Galini/Potamos tou Kampou-Laxia tis Shistis, Merinaki, Limnitis-Mersineri and possibly with the inland Skouriotissa/Katydata-Linou sanctuary near the copper deposits (

Figure 7: nos 31, 4, 19, 17 and 30). The location of the latter, amongst other functions, may have also served to secure Solian territorial claims and access to the copper-bearing north foothills of the Troodos Mountain Range (

Figure 10) (cf. [

4,

38,

39,

40]). In addition, if we accept the possibility that a Cypro-Classical sanctuary in the area of Kakopetria-Agilades (

Figure 7: no. 9) belonged to the southern end of the Solian territory, its placement front of the copper resources may have ideologically protected this kingdom’s access to the precious metal. Let us simply consider the strong military iconography, along with the presence of an Athena-like goddess and weapons among the offerings found in a votive pit in this area [

41]. Although it is risky to apply deterministic values to the location of sanctuaries, the available evidence may suggest that Agia Irini was related in some way (as a nodal point) to a network of sites that were associated with visual control of the agricultural production but also with the visual control (inland and coastal) of a metal-producing economy. Moreover, the proximity to rivers or stream beds and the location on hills or knolls with a view over agricultural land, both of which characterise the topography of Agia Irini, are features shared by many Cypriot extra-urban sanctuaries of the Archaic and Classical periods and they seem to stress the importance of control and exploitation of agricultural lands [

42] (pp. 275–276). At this point we should clarify our point: we do not refer to a direct involvement of the sanctuary in these economic activities; rather, we refer to a mental process of creating an ideational space embodying power, ideology and control [

4].

We preferred CSA over other GIS catchment approaches, since traditional catchments and tessellations rely on the assumption that the landscape is flat. As we emphasised above, in the real landscape, the size and shape of a catchment area or territory vary depending on the nature of the terrain, which is taken into account in CSA. When we run the CSA from Lapithos and Soloi (

Figure 10), it becomes clear that the sanctuary at Agia Irini lies in an almost equal walking distance of about 5–6 h from each polity. When we compare the analysis run from Agia Irini itself (

Figure 11), once again, it becomes obvious that one would need about 5–6 h to reach Soloi or Lapithos on foot. This ‘equal distance’ between Agia Irini and the two polities to which the sanctuary has been linked, as well as the landscape terrain itself and access to the site, question the very idea of Agia Irini’s greater proximity to Lapithos and seems to suggest its most likely relation to Soloi rather than to Lapithos. In addition, it becomes obvious that the sanctuary is marking the limits between two different habitats: the fertile alluvial plain of Morphou to the south and the off-shoots of the Kerynia/Pentadaktylos range projecting into Cape Kormakitis to the north. If and when this limit between different landscapes also became the frontier between two different polities is a broader historical question that is closely related to our inconclusive knowledge of early Lapithos. It seems, however, reasonable at least to suggest that due to its geographic position, Agia Irini became involved in this process of setting or signalising frontier zones. Would this, however, be an extra reason, in addition to iconography, to consider Agia Irini as a frontier sanctuary?

The LCP analysis (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13), combined with the archaeological evidence, does not allow us to further discuss the strategic placement of the Agia Irini sanctuary. Nevertheless, LCP analysis may help us better visualise the strategic placement of the Myrtou Pigadhes (

Figure 7: no. 20) sanctuary, northeast of Agia Irini. Myrtou-Pigadhes is strategically placed near the Panagra passage, on the route from Soloi to Lapithos. In fact, the Panagra passage is one of the very few entrances from Lapithos to the south via the Pentadaktylos Mountain Range. While Ulbrich, based on distance, places Myrthou-Pigadhes in the territory of Lapithos [

20] (pp. 375–376), Fourrier, based on style, places this sanctuary in the territory of Soloi [

18] (pp. 92, 113, figure 9). The Solian association of Myrtou-Pigadhes remains a valid hypothesis that is, however, difficult to prove. What may be argued with greater confidence is that both Myrtou-Pigadhes and Agia Irini seem to be placed in an area that can be described as liminal or frontier largely due to its geomorphological features: Agia Irini at the northern edge of the fertile Morphou plain and Myrtou-Pigadhes at the entrance of the Panagra passage that gives access the north coast of Cyprus.

The landscape analysis above suggests that Agia Irini, associated with Soloi both by archaeological material and by GIS analyses, is located in a strategic position between Soloi and Lapithos. The GIS analyses seem to show that natural landscape features enabled, if they did not determine, the territorialisation of the polities. In this respect, GIS analyses are similar to regional styles, which may suggest but cannot prove a territorial connection. Regardless of labelling the sanctuary at Agia Irini ‘frontier’ or not, its location (perhaps in association with the sanctuary of Myrthou-Pigadhes) and the ideological investment at the site, as read by the archaeological material analysed above, appear to contribute to making this ‘un-central’ landscape or territory ‘central,’ establishing a Solian buffer against the interests of Lapithos in the agricultural land of Morphou Bay and the copper-bearing foothills of the Troodos Mountains Range. As has been argued elsewhere [

4], specific extra-urban sanctuaries were possibly placed in frontier/liminal zones, rather than in absolute frontier lines. Whether in extra-urban settlements, along long-distance communication routes, or in frontier zones, extra-urban sanctuaries—both on the frontier and in the periphery—were linked to the evolving socio-political and socio-economic fortunes and the very formation of the territoriality of each kingdom. Sanctuaries like Agia Irini, located in frontier or liminal zones, may have served as both contact and confrontation points between polities and between settlements lying within these zones. One should remember that these places were also functional elements in the organisation of settlements and communication systems rather than merely points of (symbolic) demarcation and definition. They could act as intermediary spaces between polities and settlements and as spaces of interaction between inter- and intra-regional communities. A closer view at the pottery evidence from Agia Irini may help in understanding if and how centrality is manifested in the material evidence.

4. Pottery Analysis and the Centrality of a Sacred Place

Pottery finds from Agia Irini form an important body of evidence, only partially discussed in the 1935 publication of the site. However, the comprehensive study of pottery from the site may contribute decisively to the examination of the sanctuary not just as a site where cult was performed but also as a meeting place with political and ideological connotations, a site where different social identities were negotiated and special symbolic messages were conveyed. The latter is closely related to the possible centrality of Agia Irini. At this stage we only note that the investigation of centrality has to consider a number of factors and to verify if these are attested in the archaeological record. These elements include questions about topography, proximity to natural resources, engagement in networks of interaction between different people and/or differently organised areas, presence of cultic or economic functions, large-scale storage, consumption of food and drink, the presence of monumentality, the display and disposal of votive offerings and so forth. [

1] (pp. 94–95), [

43].

The use of pottery can be particularly helpful when examining certain of the aforementioned parameters, especially those related to economic functions, consumption and to interaction between different communities. Such an examination closely relates to questions about style and production, as well as to distribution and circulation patterns of certain products within the island.

Recent studies on Cypro-Geometric ceramics tend to complement the results of Fourrier’s analysis of Cypriot terracotta production [

18], [

36] (p. 107), [

44] (pp. 95–96, 105). In other words, both pottery and terracotta products seem to display similar fabrication and distribution patterns within the island, a fact that must mirror the formation of distinct political identities of the various Cypriot polities during the Early Iron Age. As previously stated, the vast majority of terracottas from the sanctuary at Agia Irini were associated primarily with the production of Soloi. Other parts of the island, such as Kition, Amathous, Salamis, Paphos, Lapithos and Marion, were also represented albeit in much smaller numbers.

The vast representation of regional styles in Cypriot terracotta production at Agia Irini may be evocative of a cultic place with an established importance and reputation beyond the limits of the ‘local’ area. The coexistence of terracotta statues and statuettes that belonged to different regional styles and represented different production centres and sources of influence is in essence a manifestation of a cultural, stylistic and ultimately of identity interaction, for which Agia Irini provided an ideal ground. This co-existence must have been facilitated also by the sanctuary’s position at the northern limit of the fertile Morphou plain with relatively easy access from other parts of the island and in proximity to the coastline of the Morphou bay [

18] (p. 91).

When trying to scrutinise Fourrier’s stylistic and political associations between Agia Irini and Soloi based on pottery finds, two things should be kept in mind: first, the attendance of major cultic places is usually intra-regional and therefore the stylistic assessment of pottery finds can be of use only to a certain extent; and secondly, the ceramic investigation of possible ties between Agia Irini and Soloi is hampered by our incomplete knowledge of the ceramic production of the latter during the Cypro-Geometric and early Cypro-Archaic periods. Although numerous Cypriot centres of pottery production (namely Salamis, Paphos, Amathous, Kition, Kourion, Lapithos and Kythrea) have been identified through the comparative study of fabric, surface treatment, shapes, style and decoration [

36], [

44] (with references), our knowledge of the Solian pottery production at the time of consolidation of the Cypriot polities remains elusive [

34] (p. 381).

This gap is partly counterbalanced by the results of chemical analyses of 66 terracotta statues, statuettes and clay vessels from Agia Irini, dated between the Late Bronze Age and the Cypro-Archaic period [

45]. The vast majority of the objects analysed (59 out of 66 or 89.4%) were similar in chemical composition. The coherent nature of their chemical and petrographic properties indicated that the clay beds used for their manufacture were probably located in the same area. Although dearth of comparative material hampers any secure conclusions about the precise location of these clay-beds and hence about the origin of the objects analysed, a few further points can be made: first, there is a consistency between the chemical composition of the terracotta material and that of the pottery sherds examined [

45] (p. 309). This seems to further strengthen the idea that Cypriot terracottas and pottery followed similar patterns of production and distribution. Secondly, a considerable number of the terracotta fragments that were analysed belonged to Fourrier’s Soloi production-group [

45] (pp. 302–303, table 1). The chemical homogeneity of this material may therefore hint a Solian production also for most pottery fragments that largely fell within the same chemical groups as the terracotta statues and statuettes. If this is the case, then there is an additional element to support the association between the sanctuary at Agia Irini and the realm of Soloi.

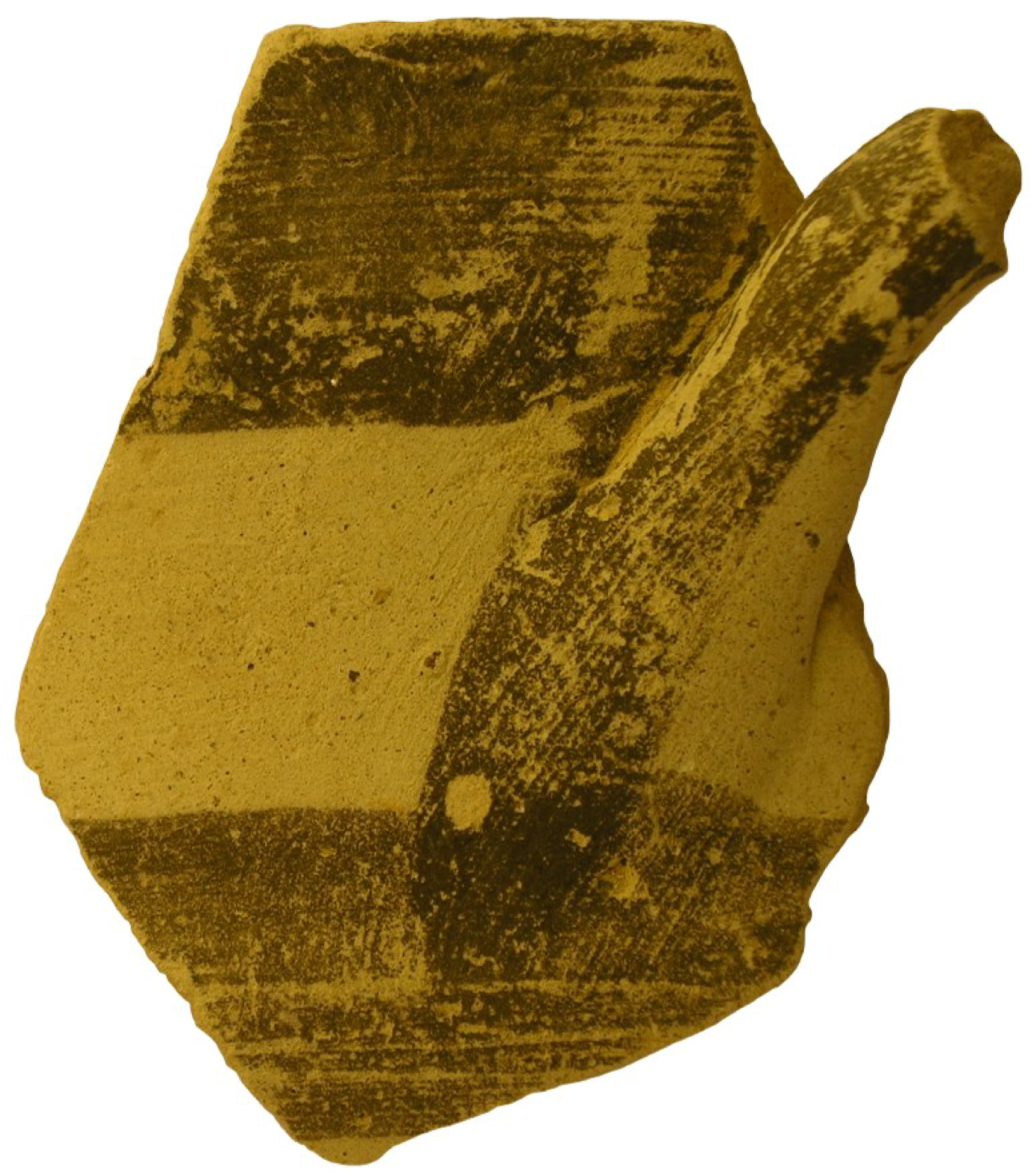

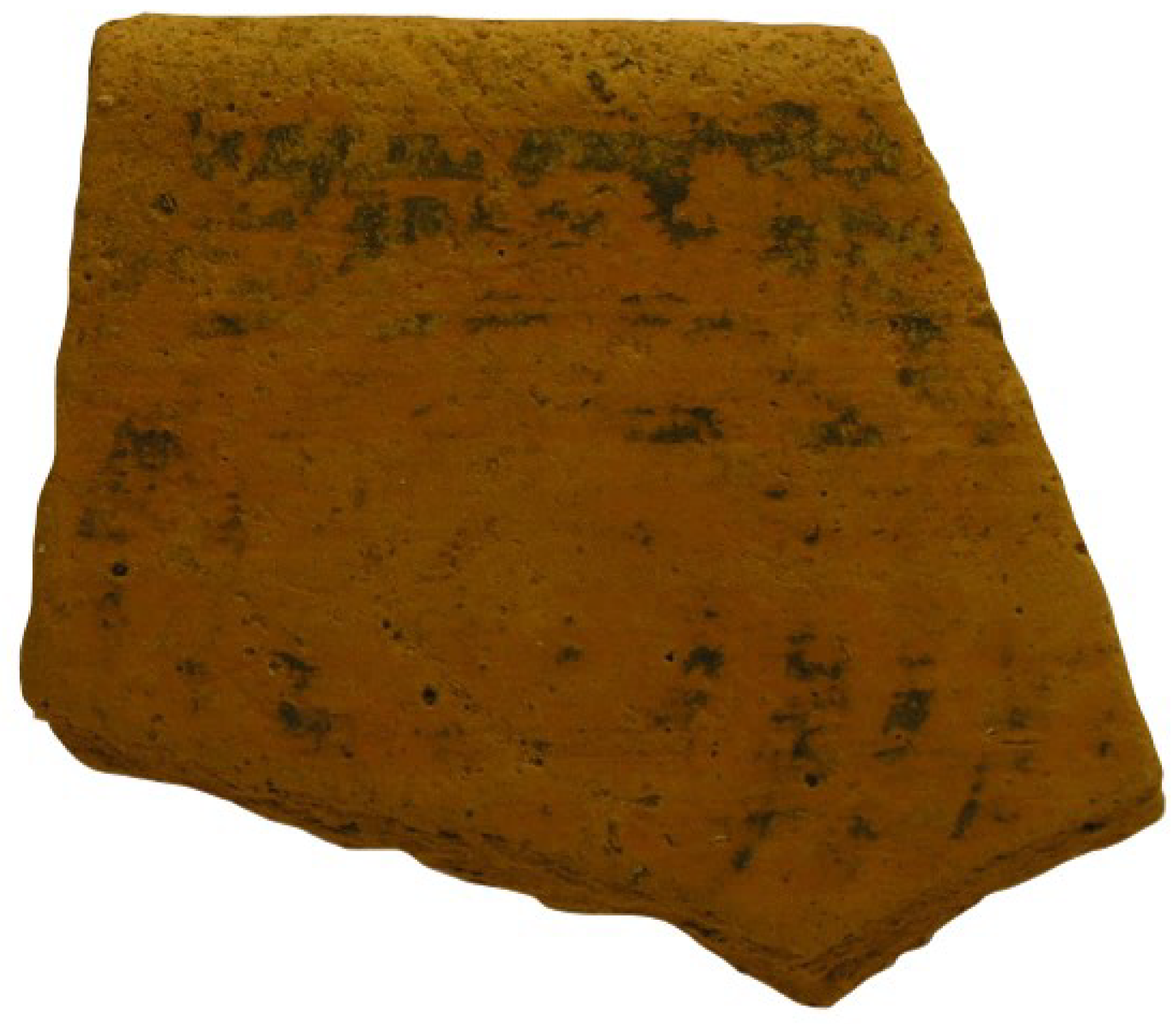

A first look at the (unpublished) pottery fragments from the sanctuary also indicates that many different parts of the island are represented in the ceramic record. Comparisons with the pottery from Lapithos, mostly burials, shows that certain ceramic types were popular both at the sanctuary of Agia Irini and at Lapithos. These include the White Painted II footed bowls with a single reserved band in the handle zone (

Figure 14) (cf. [

46] (plate VIII.1, [

47] (plate III, no. 5), [

48] (plate XLII, nos 31–32). One should also notice the similarities between White Painted I products from funerary contexts of Lapithos and the area of Agia Irini and those found in a poor cluster of tombs at Karanghas, about three miles from the coastal necropolis of Agia Irini [

49] (p. 194). A similar ceramic predilection shared by the sanctuary at Agia Irini and Cypro-Geometric burials at Lapithos is that for closed vessels of Black Slip I–II ware, either in the form of trefoil-lipped jugs or in the form of amphoriskoi (

Figure 15) [

48] (plate XLIII.35–42). The very fragmentary state of the unpublished material from Agia Irini (mostly body sherds) does not allow a secure identification of the shape although all Black Slip sherds from the sanctuary belong to closed vessels. The Black Slip technique was popular also at Amathous and Kourion during Cypro-Geometric I and II periods, with most vases belonging to the type of amphoriskoi with vertical handles [

34] (p. 377, figures 11 and 12).

Affinities between the pottery of Agia Irini and that of Lapithos can be spotted also in decoration. Although figurative decoration is extremely rare among the unpublished Iron Age pottery from the sanctuary, the Iron Age material included a White Painted I stemmed goblet (for the type see [

13] (p. 99), [

15] (figure III.3)) decorated with a male goat standing on its hind legs and eating from a tree (

Figure 16). The style of the tree on the unpublished example from the sanctuary, with the characteristic linear depiction of the branches, is almost identical to ‘palm trees’ on White Painted I vessels from burials at Lapithos [

46] (plate VIII.8), [

47] (plate III.29), [

50] (p. 494, plate XXVII.1) suggesting that the vessels were perhaps produced at the same workshop.

The influence of the pottery from Kition is perhaps indicated through the unpublished fragments of some plates decorated in the White Painted and Bichrome technique, latter occasionally combined with Black Slip (

Figure 17). This trend has been associated with the ceramic production of Kition in the Cypro-Geometric I/II period [

33] (pp. 330–301), [

34] (p. 378).

Phoenician trends, most probably originating from Kition, appear far less common at the sanctuary than at the burials excavated in the early 1970s by the Italian Mission at Agia Irini-Paleokastro [

29]. Certain pottery types recorded in the publication of the sanctuary, such as Red Slip II (IV) and III (V) ridge-necked juglets [

9] (plate CLXXXVII, bottom row, second, third and fourth from the left) belong to a Phoenicianising typology but their popularity among the unpublished fragmentary ceramics was low.

Evidence for contacts with other parts of Cyprus is also reflected in the pottery from the sanctuary at Agia Irini. The pottery production of Paphos is well represented at the sanctuary, as is manifested by the presence of Black-on-Red I (III) and II (IV) products, a ceramic technique that characterises the production of Paphos. Towards Paphos, at least as a source of influence, also points the extensive use of concentric circles on the unpublished ceramic material of Agia Irini (

Figure 18) [

9] (pp. 776, 812; cf. figures CLXXXVII, CLXXXVIII for vases, mostly jugs and juglets, decorated with concentric circles). This motif was particularly popular in the area of Paphos from the Cypro-Geometric II period onwards, where it was applied to vessels of White Painted and from Cypro-Geometric III also of Black-on-Red Ware [

34] (pp. 378–380).

Preliminary investigation of pottery from the sanctuary at Agia Irini offers a glimpse of the various sources of ceramic influence which must have extended from Lapithos in the north to Kition and Paphos in the south. In this respect and although this should be seen as a provisional conclusion, pottery from the sanctuary seems to confirm stylistic influence and affiliations as these were described by the terracotta analysis of Fourrier. The possible role of Soloi in this ceramic interplay with Agia Irini may be approached only indirectly. Previously mentioned results of chemical analyses can be corroborated by comparisons with the sanctuary at Myrtou-Pigadhes [

51], a cultic place situated close to Agia Irini that was also possibly related to the realm of Soloi [

18] (p. 92). Myrtou-Pigadhes prospered in the Late Bronze Age. The final occupation of this sanctuary (Period 8) produced pottery dated between the Cypro-Geometric I and Cypro-Archaic I, although, as in the case of the Agia Irini sanctuary, the unbroken continuity of the site remains questionable.

Iron Age pottery from Myrtou-Pigadhes [

51] (pp. 60–74) displays a wide range of shapes, techniques and styles that indicate connections with different parts of the island. However, there are some similarities with the pottery from Agia Irini (both published and unpublished). These may be due to similar political/cultural associations for the two neighbouring sanctuaries and can be summarised as follows: presence at both sites of stemmed goblets, although the ones from Agia Irini are usually later and date to the Cypro-Archaic I period [

9] (plate CLXXXVII, last row: from Period 5), [

51] (p. 63, figure 26); Black Slip jugs are well attested at both sites [

9] (plate CLXXXVII.2), [

51] (p. 70, figure 29). In the case of Myrtou-Pigadhes Black Slip vessels also include open shapes such as dishes, the presence of which at Agia Irini is dubious. Another common ceramic feature in both sanctuaries is the presence of small ridge-necked juglets produced in the White Painted and Black-on-Red technique, the majority of which are decorated with concentric circles [

9] (plate CLXXXVIII.1, Period 4, third row), [

51] (p. 65, figure 27; p. 70, figure 29). Moreover, the large number of bowls (both deep and shallow) and plates is a common feature both at Myrtou-Pigadhes and at Agia Irini [

9] (plate CLXXXVIII.1, Period 4, two bottom rows, plate CLXXXVIII.2, Period 6, two bottom rows), [

51] (p. 63, figure 26, p. 70, figure 29, p. 71, figure 30) suggesting that drinking and dining were important aspects of the cultic activity at both sites. With regard to Agia Irini, the presence of Plain White jugs, bowls and plates [

9] (pp. 774, 777), confirmed also by the examination of the unpublished pottery from the sanctuary (

Figure 19), stresses the importance of food and drink consumption for which unassuming low-cost pottery was also utilised. Dining and drinking were embedded in cult and probably also favoured meeting and societal negotiation between different groups of people. Such consumption patterns were verified also through excavation at Agia Irini, since large waste material consisting of ash, animal bones and carbonised matter was found intermixed with pottery sherds [

10] (p. 152), indicating both the sacrifice and the consumption of animals. That food preparation probably involved grinding, is suggested by the presence of mortaria, both in the published and in the unpublished material. One of them, classified as Plain White V (

Figure 20) [

9] (p. 773, no. 2747, plate CLXXXVII.4, Period 5, first row, second from left), was used as a cover of a pithos, suggesting a close link between storage and food consumption. Mortaria of this type and fabrication are a common Cypriot product of the 7th and 6th centuries BC and occur also outside of Cyprus, for example at Miletus [

52] (pp. 320–321, figure 1a). Their use may have been symbolic as well as practical, since ingredients grinded in them could be used to spice up the banquet or any food that was meant to be consumed in a slightly more formal setting [

52].

When looking for further evidence of storage, it becomes evident that storage at Agia Irini is mostly linked to the earliest history of the site. Storage vessels—primarily pithoi—from Period 1, dated by the excavators to the Late Cypriot III, were included in the publication of the sanctuary [

9] (p. 774, nos. 2775, 2781–2783). Although some of the pithos fragments were found in Rooms V and VI that constituted the cult house proper [

14] (pp. 54–57), the northern unit of the Late Bronze Age complex (Rooms I, II and III) that were of secular character, also produced pithoi and other vases that were not described in the publication of the site [

14] (p. 57). This incomplete knowledge of the pithos fragments produced at Agia Irini does not allow comprehensive views of the site’s storage capacity in the Late Bronze Age; nonetheless, this must have been larger than what is implied by the publication. When moving to the Iron Age, when the site has a purely

temenos function, storage vessels constitute, once again, just a small fraction of the published material. However, the sanctuary’s engagement in economic transactions and the possibility of storage is clearly reflected on the presence of pithoid vessels or jars, as in the case of a Plain White IV torpedo jar from Period 5 (ca. 600–540 BC) [

9] (p. 681, no. 201, plate CLXXXVII).

Associations between pottery finds and architecture are questionable at Agia Irini, especially for the Iron Age phase of the sanctuary. Although most of the Late Bronze Age finds came from the three building-complexes that were dated to Period 1 (Building I–X, Walls 1–25) [

9] (p. 665, figure 263), Iron Age pottery came from the whole area of the

temenos even though the density was greater near the altar. With the exception of the altar, the

peribolos wall and the so-called tree-enclosure [

9] (p. 665, figure 263) there was no major architectural element at the sanctuary of Agia Irini during the Iron Age. Due to the convoluted stratigraphy of the sanctuary it is hard to establish at this stage clear associations between pottery finds and architectural elements. Nevertheless, this pottery analysis shows that the sanctuary of Agia Irini displays certain features that tend to support its role as a central meeting place. These can be summarised in the plurality of pottery styles represented at the sanctuary that suggest contacts and interaction with many different parts of the island, as well as in the consumption of food and drink, based primarily on the shapes of the pottery produced during the excavation of the site. The pottery from the sanctuary, both published and unpublished, belongs to common types of Cypriot fine ware that are well-attested throughout the island. Special features are rather rare, the main exception being the figured decoration of a grazing male goat depicted on a White Painted I stemmed goblet, a suitable subject for a sanctuary that was closely associated with the control of a fertile agricultural area.

What also remains dubious, based on pottery evidence alone, is the designation of the sanctuary’s political affiliation that usually oscillates between Soloi and Lapithos. Ceramic affinities with the area of Lapithos do exist but this is hardly surprising given the openness of Agia Irini sanctuary to the pottery styles of many areas of Cyprus. The investigation of ceramic links between Agia Irini and Soloi, with which the sanctuary was most possibly associated, is hampered by our incomplete knowledge of the Cypro-Geometric and early Cypro-Archaic Solian production. However, comparisons between Agia Irini and the neighbouring sanctuary at Myrtou-Pigadhes, outline resemblances in both the sequence of phases and in the ceramic record. Such resemblances may reflect that Iron Age Agia Irini was the main/central sanctuary within a larger network of cultic places situated in liminal areas between different areas or polities.