Spatial and Temporal Variation of Vegetation NPP in a Typical Area of China Based on the CASA Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

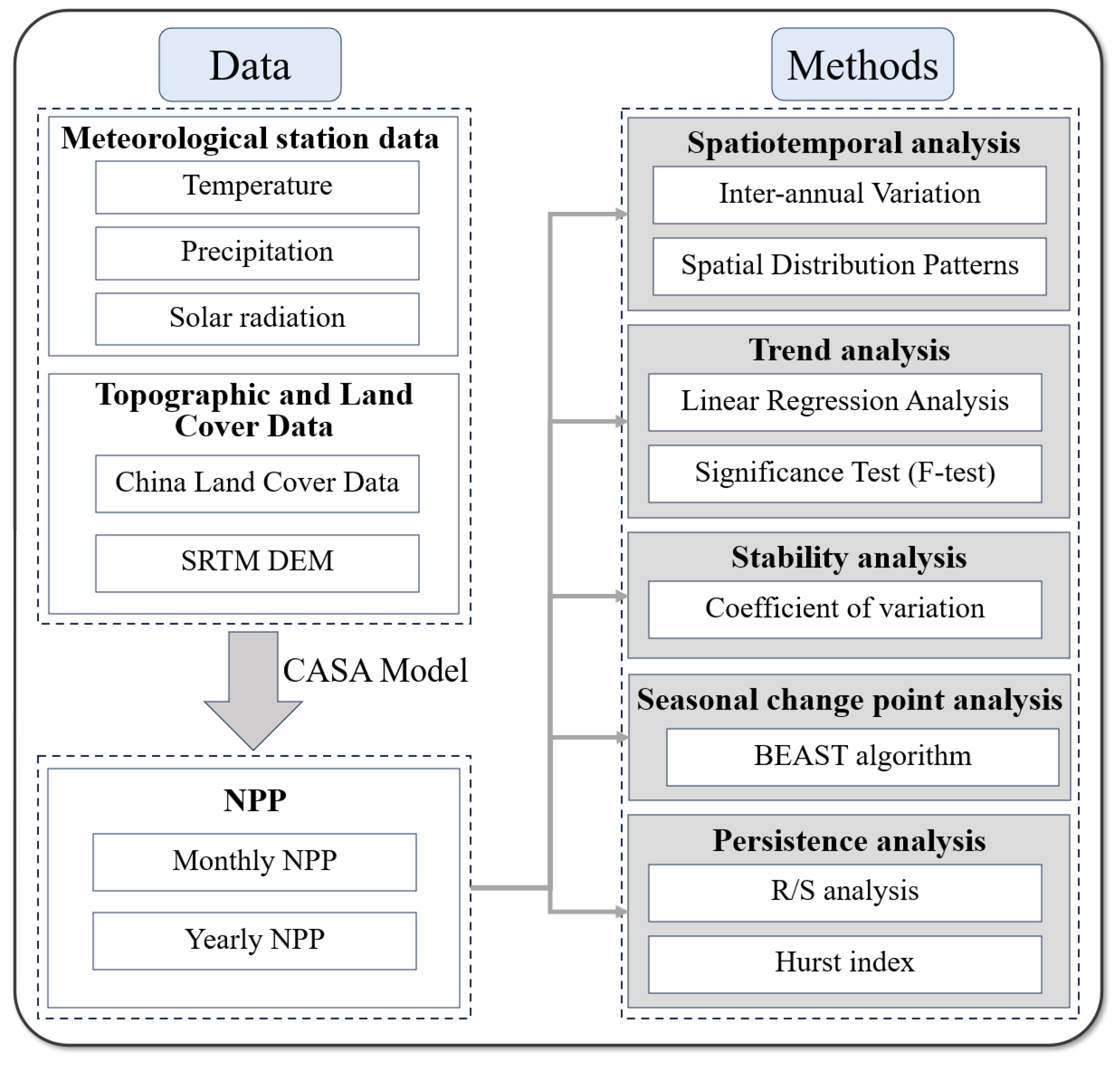

2. Materials and Methods

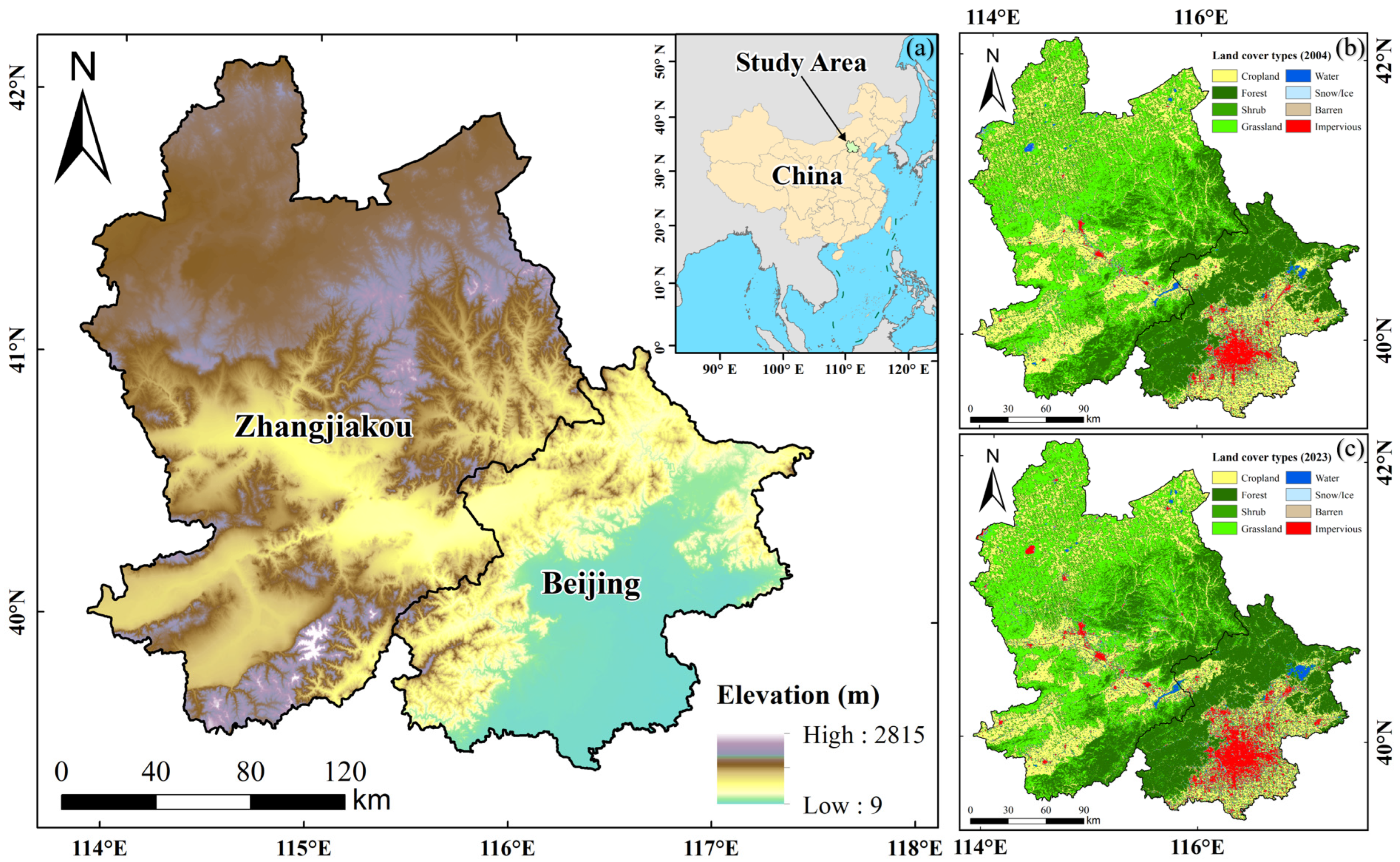

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. The CASA Model

2.3.2. The BEAST Detection

2.3.3. Trend Analysis

2.3.4. Coefficient of Variation

2.3.5. Hurst Index

3. Results

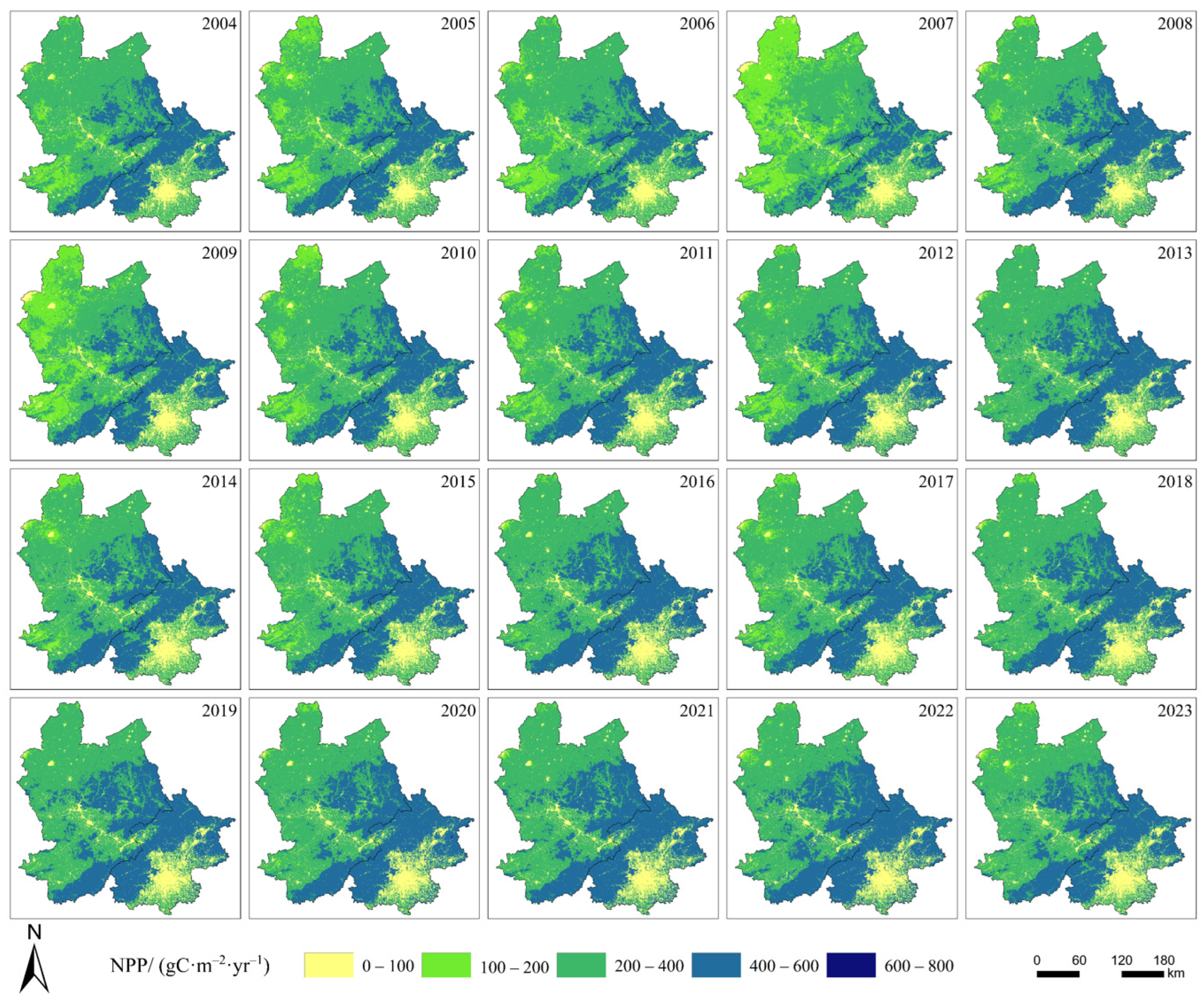

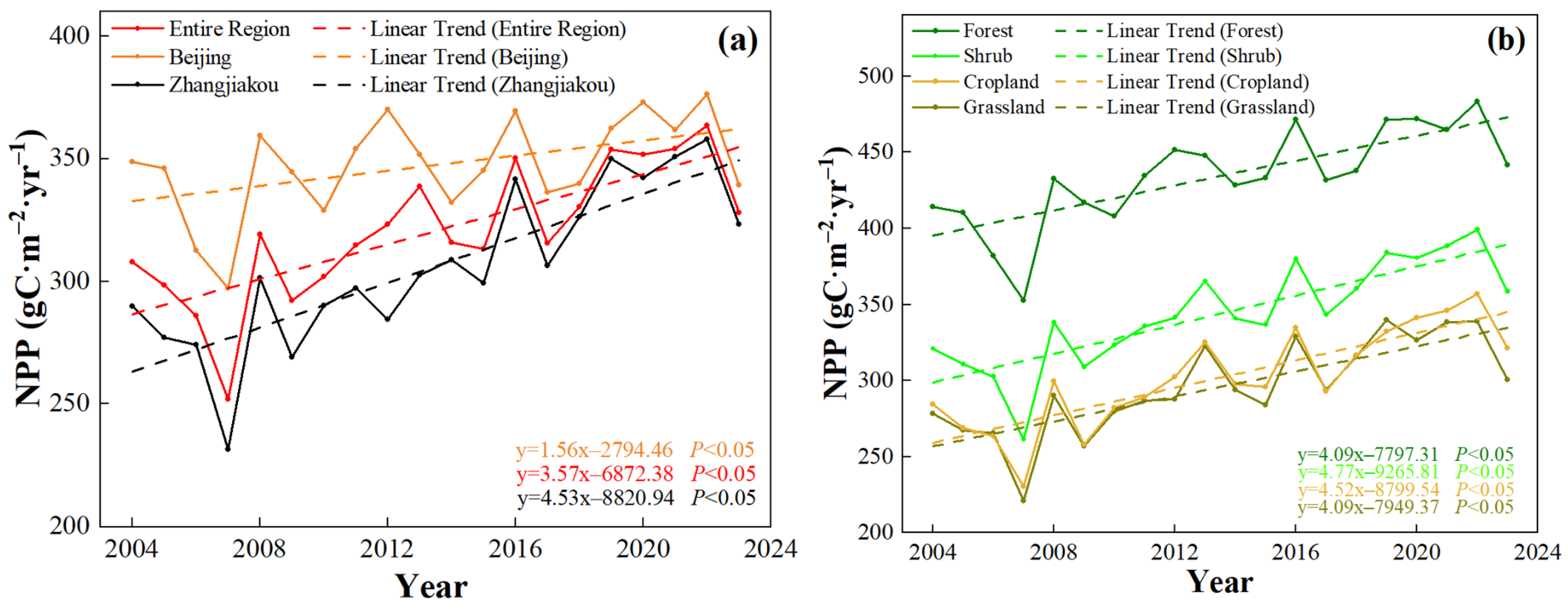

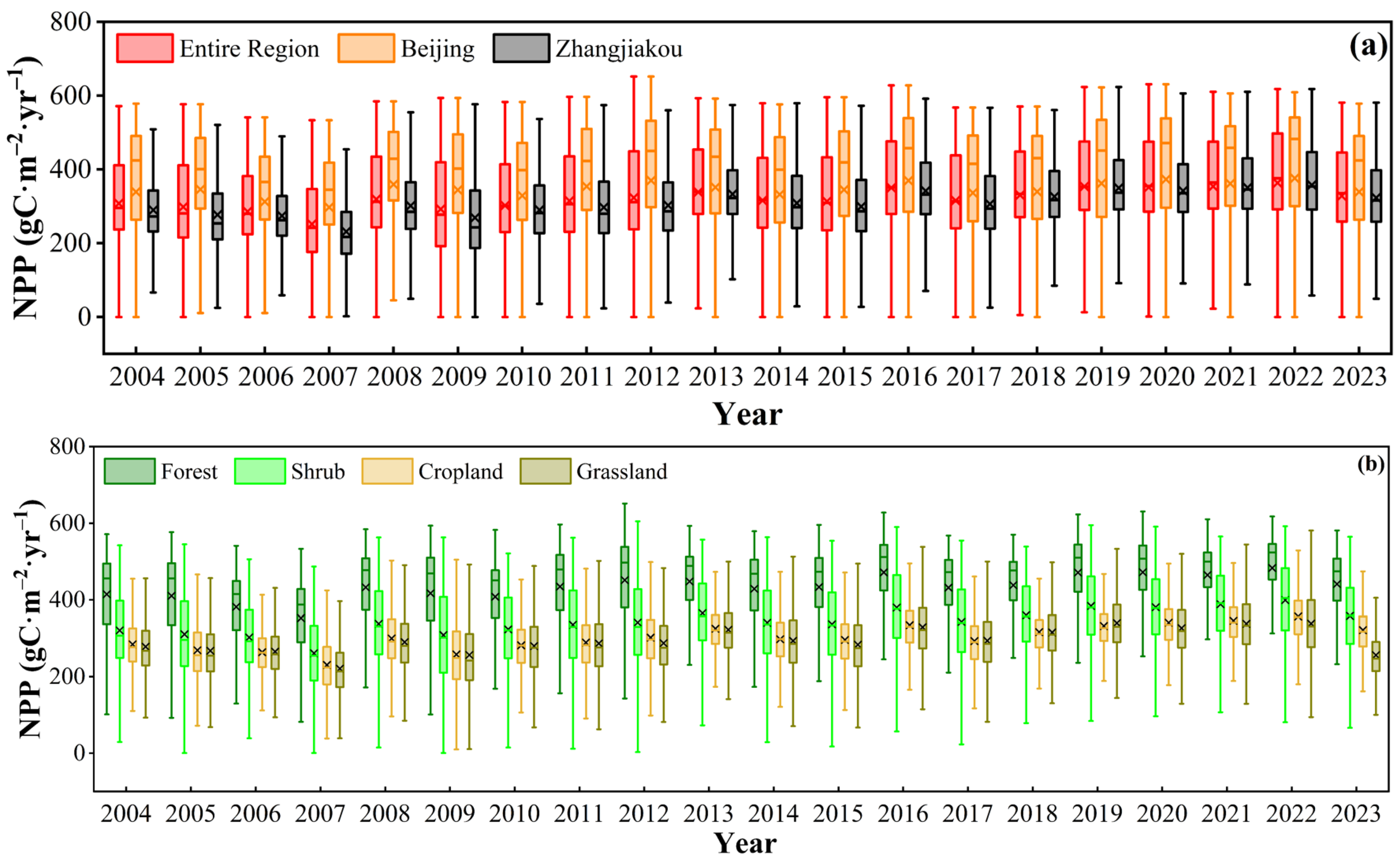

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variations in NPP

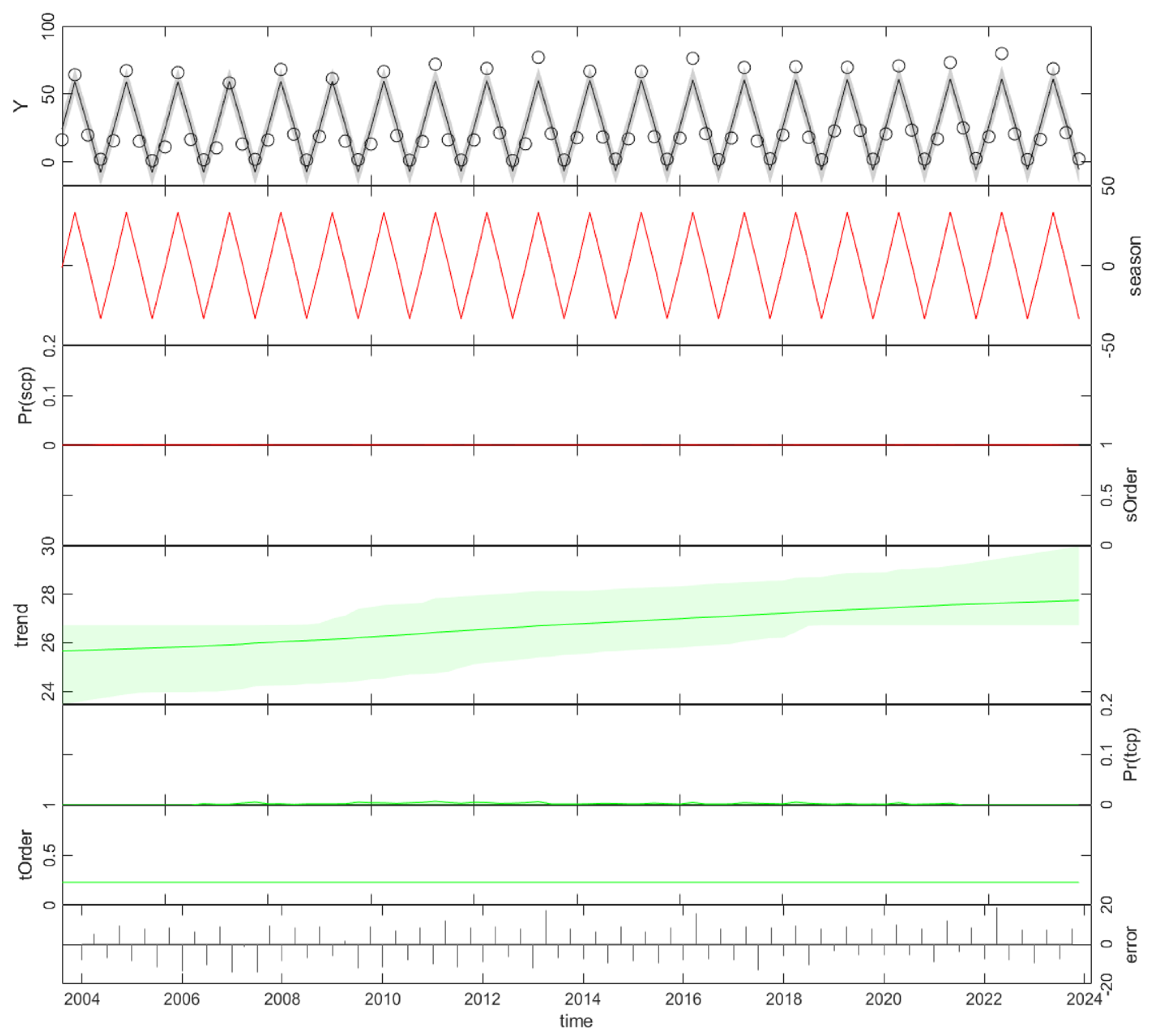

3.2. Seasonal Change-Point Detection of NPP Time Series

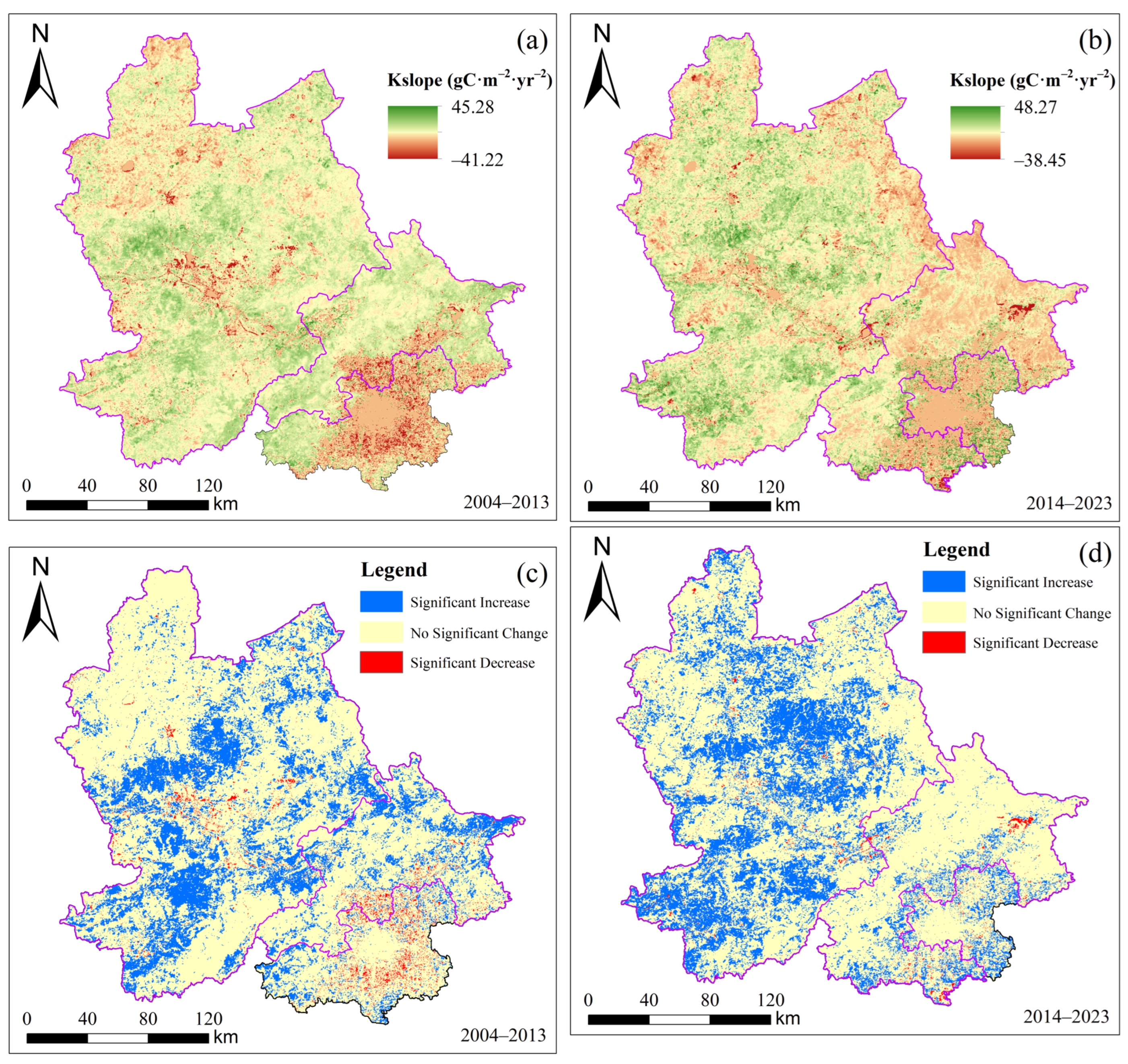

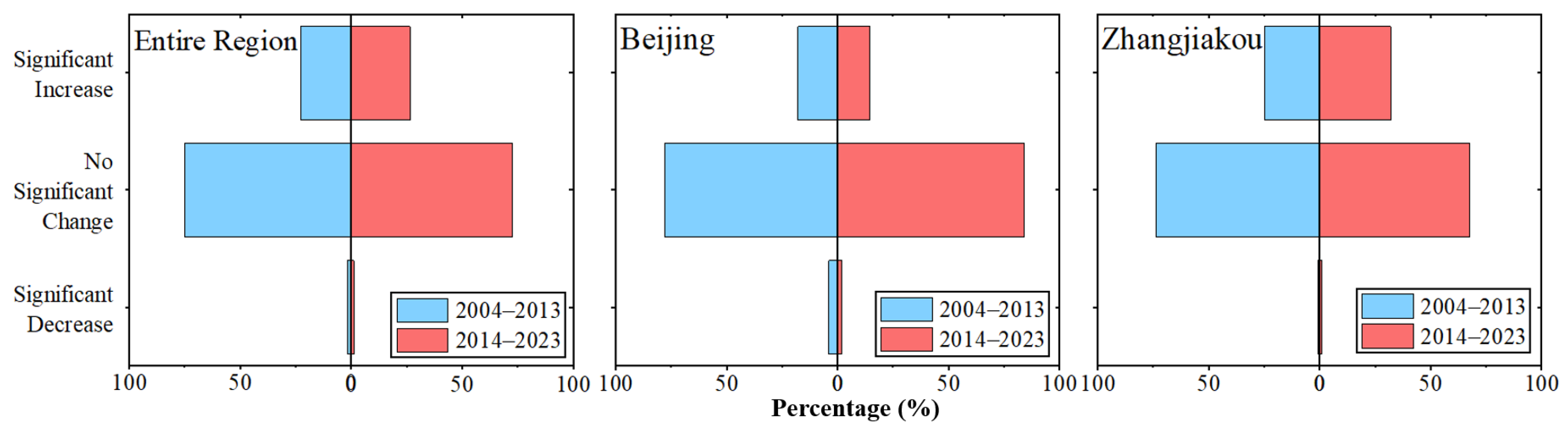

3.3. Spatiotemporal Trends in NPP

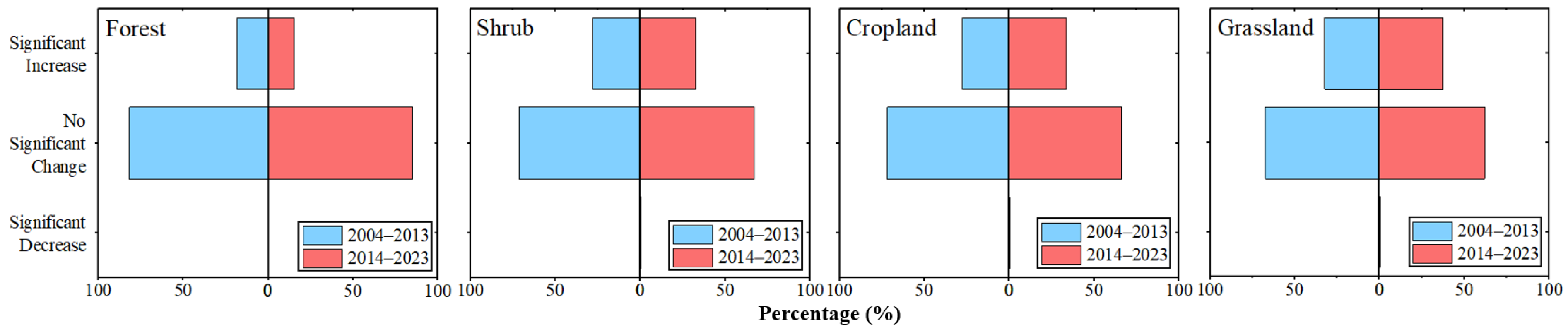

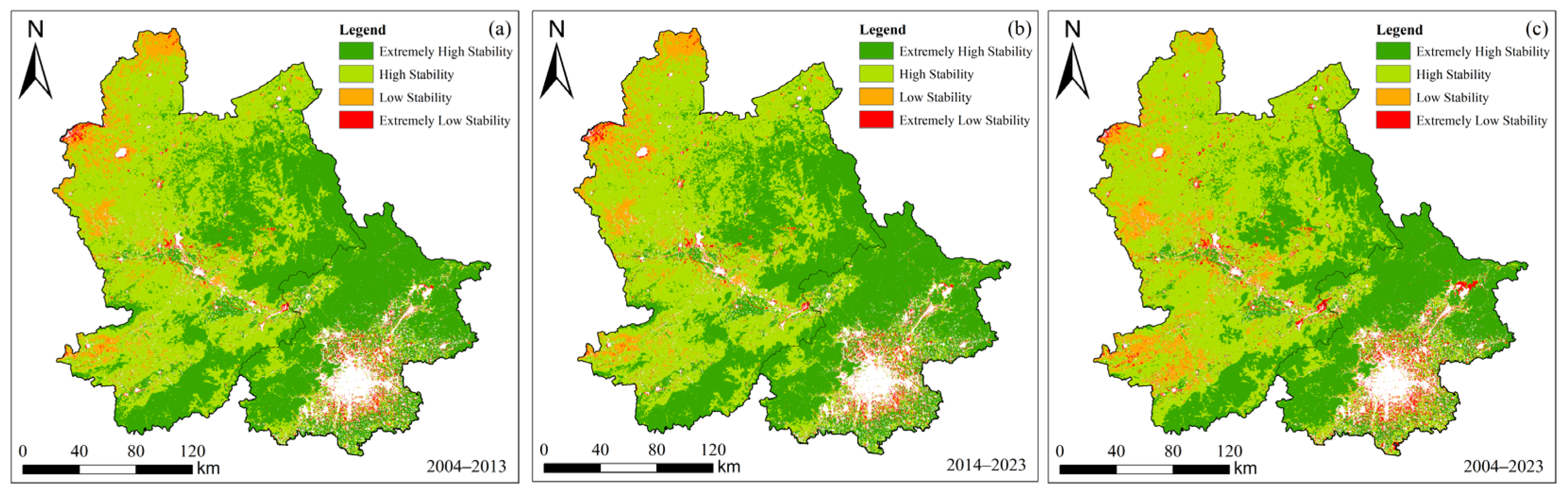

3.4. Spatiotemporal Stability of NPP

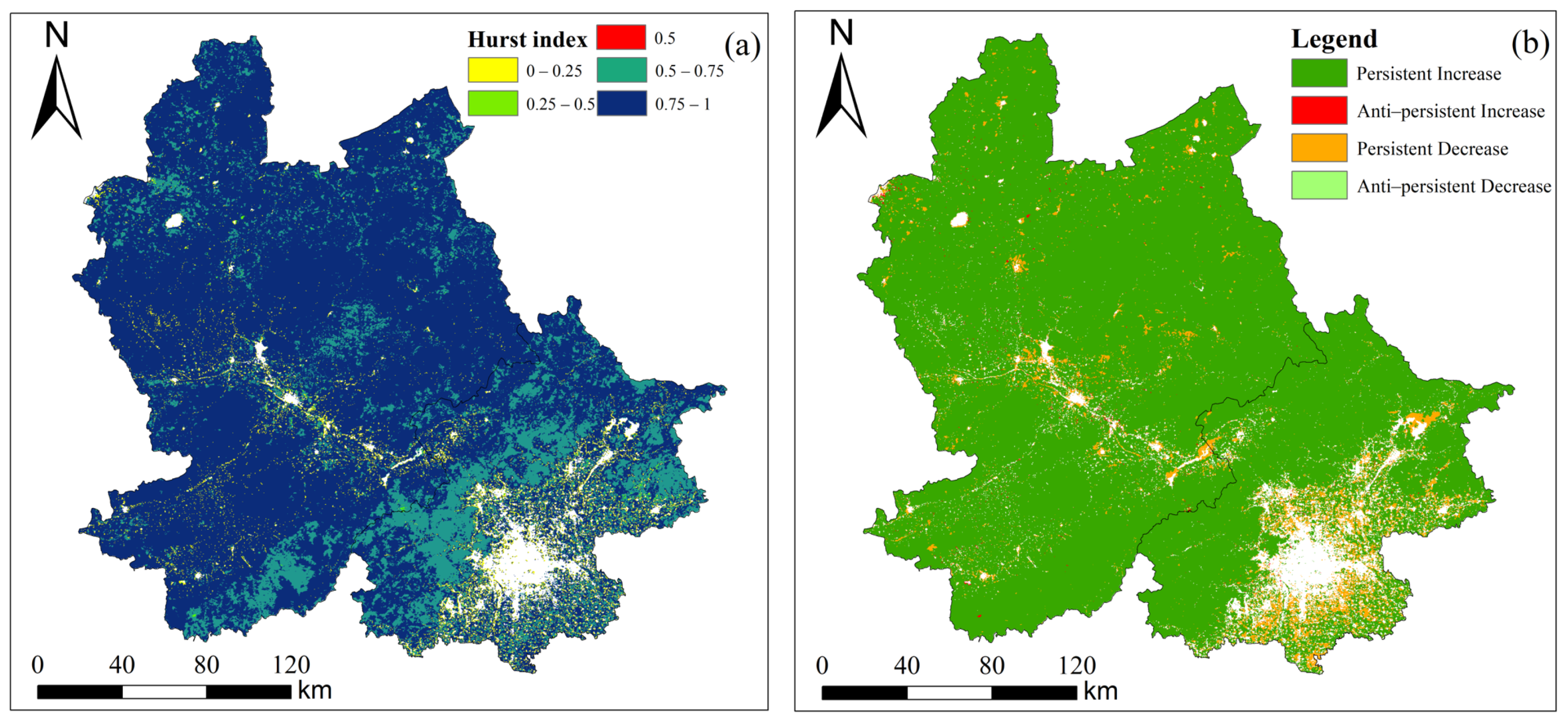

3.5. Persistence Analysis of NPP Trends

4. Discussion

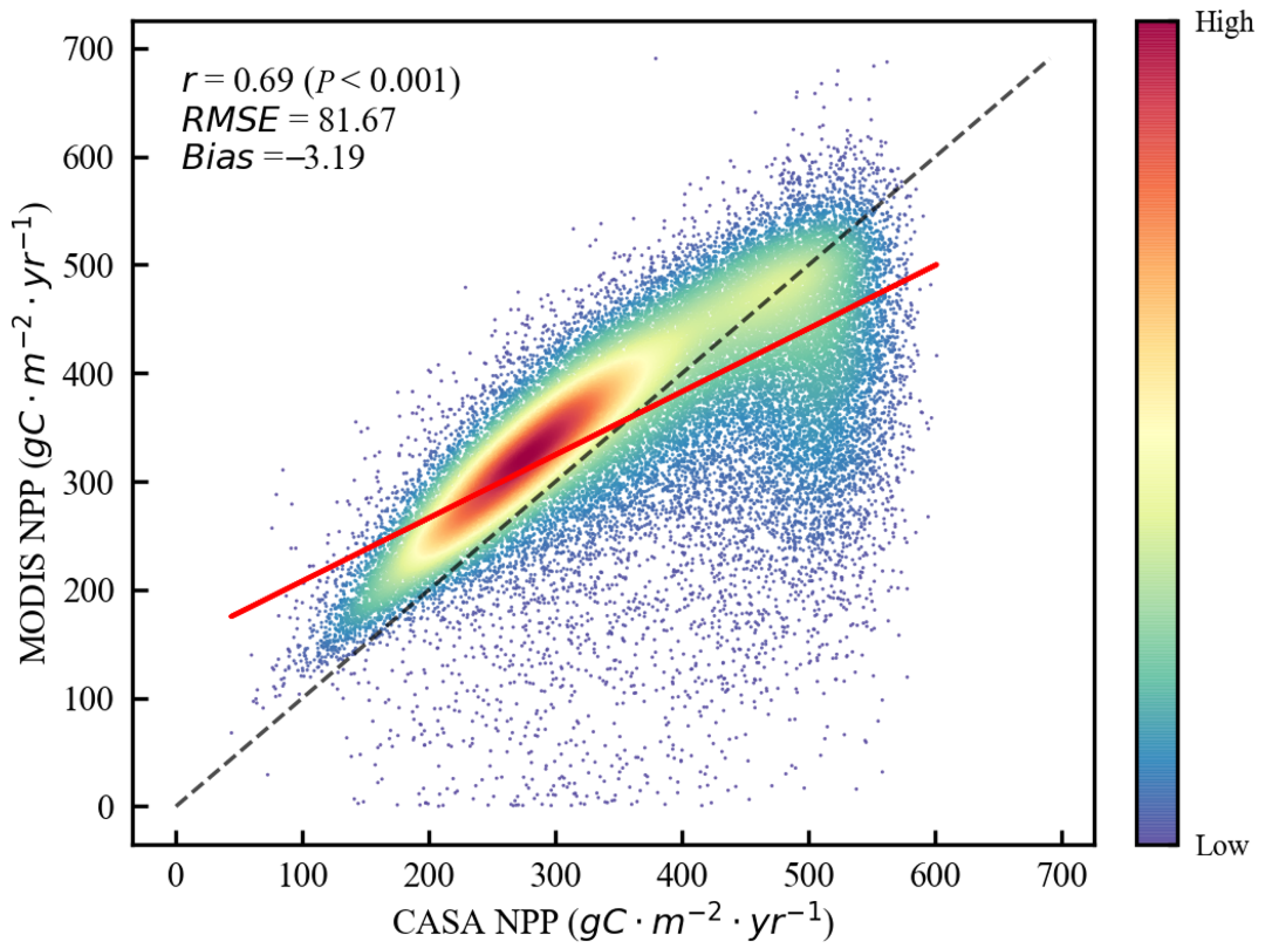

4.1. Accuracy Assessment of NPP Estimation and Uncertainty Analysis

4.2. Impact of Ecological Restoration Projects on NPP

5. Conclusions

- Vegetation NPP exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with relatively stable high- and low- value zones during the study period. High NPP values are mainly concentrated in forest-dominated areas (e.g., western and northern Beijing and the northeastern part of Zhangjiakou), whereas lower values are primarily observed in Beijing’s southeastern plain, characterized by extensive built-up and agricultural landscapes. Pixel-level boxplots further indicate stronger intra-regional variability in Beijing than in Zhangjiakou, reflecting the coexistence of high-productivity forests and relatively low-productivity built-up/cropland areas.

- Annual mean NPP demonstrates significant increasing trends for the entire study area as well as for Beijing and Zhangjiakou during 2004–2023, with interannual increase rates of 3.57, 1.56, and 4.53 gC·m−2·yr−2, respectively. Despite the overall upward tendency, evident interannual fluctuations occur, with minimum values in 2007 and maximum values in 2022. Trend maps and category statistics indicate that positive trends dominate most of the study area, with a slight expansion of increasing areas in the later sub-period. BEAST results further suggest a stable NPP seasonal cycle during 2004–2023, with no significant seasonal change points.

- CV-based stability analysis indicates that most areas exhibit high to extremely high stability, whereas low-stability zones are mainly associated with urban expansion areas and surrounding croplands, as well as some grassland regions. Hurst-index results indicate that persistently increasing NPP trends account for more than 90% of the study area, while persistently decreasing trends occupy approximately 5.25%, mainly linked to Beijing’s urban expansion zones. Mean H values are higher in Zhangjiakou than in Beijing, and higher in grassland and cropland than in forest, supporting stronger persistence in these areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, H.; Chen, Y.; Dong, G.; Li, J. Quantitative analysis of spatiotemporal changes and driving forces of vegetation net primary productivity (NPP) in the Qimeng region of Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, V.S.; Pathak, R.; Rawal, R.S.; Bhatt, I.D.; Sharma, S. Long-term ecological monitoring on forestland ecosystems in Indian Himalayan Region: Criteria and indicator approach. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Srivastava, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Arya, V.S. Spatio-temporal variability analysis of evapotranspiration, water use efficiency and net primary productivity in the semi-arid region of Aravalli and Siwalik range, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 7897–7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Behrenfeld, M.J.; Randerson, J.T.; Falkowski, P. Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 1998, 281, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wu, J.; Shen, Q.; Liu, L.; Lin, J.; Yang, J. Estimation of the net primary productivity of winter wheat based on the near-infrared radiance of vegetation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, L.; Qi, Q. Temperature Mediates the Dynamic of MODIS NPP in Alpine Grassland on the Tibetan Plateau, 2001–2019. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of China’s grassland NPP and its driving factors. Chin. J. Ecol. 2020, 39, 349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, Z. Relative importance of climate change and human activities for vegetation changes on China’s silk road economic belt over multiple timescales. Catena 2019, 180, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, K.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Du, T.; Zhang, H. Evaluation of spatiotemporal variation and impact factors for vegetation net primary productivity in a typical open-pit mining ecosystem in northwestern China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 3756–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.C.; Birdsey, R.A.; Pan, Y. Biomass and NPP estimation for the mid-Atlantic region (USA) using plot-level Forestland inventory data. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 1174–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldocchi, D.D. Assessing the eddy covariance technique for evaluating carbon dioxide exchange rates of ecosystems: Past, present and future. Glob. Change Biol. 2003, 9, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Randerson, J.T.; Malmström, C.M. Global net primary production: Combining ecology and remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 51, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.P.; Neumann, M.; Vogt, J.; Cammalleri, C.; Lang, M. Assessing effects of drought on tree mortality and productivity in European forestlands across two decades: A conceptual framework and preliminary results. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 932, p. 012009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Gang, C.; Zhou, F.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Zhao, C. Quantitative assessment of the individual contribution of climate and human factors to desertification in northwest China using net primary productivity as an indicator. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 48, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pei, F.; Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z. Global urban expansion offsets climate-driven increases in terrestrial net primary productivity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Lai, C.; Wu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, X.; Lian, Y. Response of net primary production to land use and land cover change in mainland China since the late 1980s. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, C. Spatiotemporal Variation and Climate Influence Factors of Vegetation Ecological Quality in the Sanjiangyuan National Park. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, D.; Xu, H.; Zhong, X. Assessing the spatiotemporal variation of NPP and its response to driving factors in Anhui province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 14915–14932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Sanchez-Azofeifa, G.A.; Duran, S.M.; Calvo-Rodriguez, S. Estimation of aboveground net primary productivity in secondary tropical dry forestlands using the Carnegie–Ames–Stanford approach (CASA) model. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 075004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Wang, C. Evaluating the Performance of the Greenbelt Policy in Beijing Using Multi-Source Long-Term Satellite Observations from 2000 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiao, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Multi-scale spatial analysis of satellite-retrieved surface evapotranspiration in Beijing, a rapidly urbanizing region under continental monsoon climate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 20402–20414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wu, J. Influence of Beijing Winter Olympic Games Construction on Vegetation Coverage around Zhangjiakou Competition Zone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, Q.; Hua, L. NPP spatial and temporal pattern of vegetation in Beijing and its factor explanation based on CASA model. Remote Sens. Land Resour. 2015, 27, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, W.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, Y. China Regional 250m Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Data Set (2000–2024); National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. 30 m annual land cover and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2021, 2021, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar]

- Amantai, N.; Meng, Y.; Song, S.; Li, Z.; Hou, B.; Tang, Z. Spatial–Temporal Patterns of Interannual Variability in Planted Forestlands: NPP Time-Series Analysis on the Loess Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberoglu, S.; Donmez, C.; Click, A. Modelling climate change impacts on regional net primary productivity in Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Yang, L.; Li, Z. Soil Moisture Variations with Land Use along the Precipitation Gradient in the North–South Transect of the Loess Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Han, W.; Liu, Y. Cumulative effects of drought have an impact on net primary productivity stability in Central Asian grasslands. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Xie, H.; Zhuoge, Z. The Impact of Human Activities on Net Primary Productivity in a Grassland Open-Pit Mine: The Case Study of the Shengli Mining Area in Inner Mongolia, China. Land 2022, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Cui, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Du, T.; Zhang, H. Construction and analysis of a method for grading long-term vegetation carbon sink in waste dumps of an open-pit coal mine. Coal Geol. Explor. 2024, 52, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Liang, B. Spatiotemporal variation and prediction of NPP in Beijing–Tianjin-Hebei region by coupling PLUS and CASA models. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.S.; Randerson, J.T.; Field, C.B.; Maston, P.A.; Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Klooster, S.A. Terrestrial ecosystem production: A process model based on global satellite and surface data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1993, 7, 811–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shao, Z.; Fu, P.; Zhuang, Q.; Chang, J.; Jing, P.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, F. Unraveling the impact of urban expansion on vegetation carbon sequestration capacity: A case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, J. Estimation of net primary productivity of Chinese terrestrial vegetation based on remote sensing. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2007, 31, 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.G.; Wulder, M.A.; Hu, T.; Bright, R.; Wu, Q.; Qin, H.; Li, Y.; Toman, E.; Zhang, X.; Brown, M. Detecting change-point, trend, and seasonality in satellite time series data to track abrupt changes and nonlinear dynamics: A Bayesian ensemble algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Abuduwaili, J.; Zhang, J. Assessing the intensity of the water cycle utilizing a Bayesian estimator algorithm and wavelet coherence analysis in the Issyk-Kul Basin of Central Asia. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 52, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Toman, E.M.; Chen, G.; Shao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, K.; Feng, Y. Mapping fine-scale human disturbances in a working landscape with Landsat time series on Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 176, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazmardi, S.; Sadrykia, M.; Rezazadeh, M. Analysis of spatiotemporal household water consumption patterns and their relationship with meteorological variables. Urban Clim. 2023, 52, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yan, W.; Cai, Y.; Deng, F.; Qu, X.; Cui, X. How does the Net primary productivity respond to the extreme climate under elevation constraints in mountainous areas of Yunnan, China? Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ma, X.; Dou, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, C. Impacts of climate change on vegetation phenology and net primary productivity in arid Central Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 149055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Impacts of climate, phenology, elevation and their interactions on the net primary productivity of vegetation in Yunnan, China under global warming. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Temporal-spatial analysis of vegetation coverage dynamics in Beijing–Tianjin-Hebei metropolitan regions. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 7418–7426. [Google Scholar]

- Ouma, Y.O.; Cheruyot, R.; Wachera, A.N. Rainfall and runoff time-series trend analysis using LSTM recurrent neural network and wavelet neural network with satellite-based meteorological data: Case study of Nzoia hydrologic basin. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, X.; Khaw, K.W.; Lee, M. The efficiency of run rules schemes for the multivariate coefficient of variation in short runs process. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2022, 51, 2942–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puggard, W.; Niwitpong, S.A.; Niwitpong, S. Confidence Intervals for Common Coefficient of Variation of Several Birnbaum–Saunders Distributions. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.; Ślepaczuk, R. Applying Hurst Exponent in pair trading strategies on Nasdaq 100 index. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2022, 592, 126784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, P.; Lee, M. Forecasting the Volatility of the Stock Index with Deep Learning Using Asymmetric Hurst Exponents. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Chen, G.; Xing, Y.; Xu, H.; Tian, Z.; Ma, Y.; Cui, J.; Li, D. Spatial and temporal variation of vegetation NPP and analysis of influencing factors in Heilongjiang Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Cui, K.; Zheng, J. Long time series spatiotemporal variations in NPP based on the CASA model in the eco-urban agglomeration around Poyang lake, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ciais, P.; Sönke, Z. Changes in climate and land use have a larger direct impact than rising CO2 on global river runoff trends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15242–15247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Guo, W.; Wang, H. Times series dynamic assessment of ecological environment quality in Beijing–Tianjin-Hebei region based on GEE and RSEI. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2024, 39, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Wu, Z.; Du, Z.; Zhang, H. Variation in fractional vegetation cover and its attribution analysis of different regions of Beijing–Tianjin Sand Source Region, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 2895–2905. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Xie, G. Spatio-temporal changes of water conservation service in the Beijing–Tianjin sandstorm source control project area. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 7530–7541. [Google Scholar]

| Data Type | Name | Time Span | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI dataset | China regional 250 m normalized difference vegetation index data set | 2004–2023 | 250 m | monthly | https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/ (accessed on 29 December 2025) |

| Climate dataset | temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation | 2004–2023 | Interpolated to 250 m | monthly | http://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 24 March 2025) |

| Land cover dataset | China Land Cover Dataset | 2004–2023 | 30 m | yearly | https://zenodo.org/ (accessed on 30 December 2025) |

| Elevation | SRTM DEM | 2004–2023 | 30 m | - | https://earthengine.google.com/ (accessed on 30 December 2025) |

| CV-Value | Stability Level |

|---|---|

| CV ≤ 0.1 | extremely high stability |

| 0.1 < CV ≤ 0.2 | high stability |

| 0.2 < CV ≤ 0.3 | low stability |

| CV > 0.3 | extremely low stability |

| Kslope | H Value | NPP Trend–Persistence Category |

|---|---|---|

| Kslope > 0 | 0.5 < H < 1 | Persistent increase |

| Kslope > 0 | 0 < H < 0.5 | Anti-persistent increase |

| Kslope < 0 | 0.5 < H < 1 | Persistent decrease |

| Kslope < 0 | 0 < H < 0.5 | Anti-persistent decrease |

| Any | H = 0.5 | Uncertain |

| Category | Mean CV | |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative regions | Beijing | 0.22 |

| Zhangjiakou | 0.17 | |

| Land cover types | Forest | 0.08 |

| Shrub | 0.11 | |

| Cropland | 0.14 | |

| Grassland | 0.14 | |

| Category | Mean Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative regions | Beijing | 0.65 |

| Zhangjiakou | 0.84 | |

| Land cover types | Forest | 0.78 |

| Shrub | 0.85 | |

| Grassland | 0.87 | |

| Cropland | 0.85 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cui, K.; Yang, F.; Dong, Q.; Wang, Z.; Du, T.; Wang, Z. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Vegetation NPP in a Typical Area of China Based on the CASA Model. Land 2026, 15, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020237

Cui K, Yang F, Dong Q, Wang Z, Du T, Wang Z. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Vegetation NPP in a Typical Area of China Based on the CASA Model. Land. 2026; 15(2):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020237

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Kuankuan, Fei Yang, Qiulin Dong, Zehui Wang, Tianmeng Du, and Zhe Wang. 2026. "Spatial and Temporal Variation of Vegetation NPP in a Typical Area of China Based on the CASA Model" Land 15, no. 2: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020237

APA StyleCui, K., Yang, F., Dong, Q., Wang, Z., Du, T., & Wang, Z. (2026). Spatial and Temporal Variation of Vegetation NPP in a Typical Area of China Based on the CASA Model. Land, 15(2), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15020237