Measurement and Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Conflicts Under the Orientation of Carbon Neutrality in Jiangsu Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

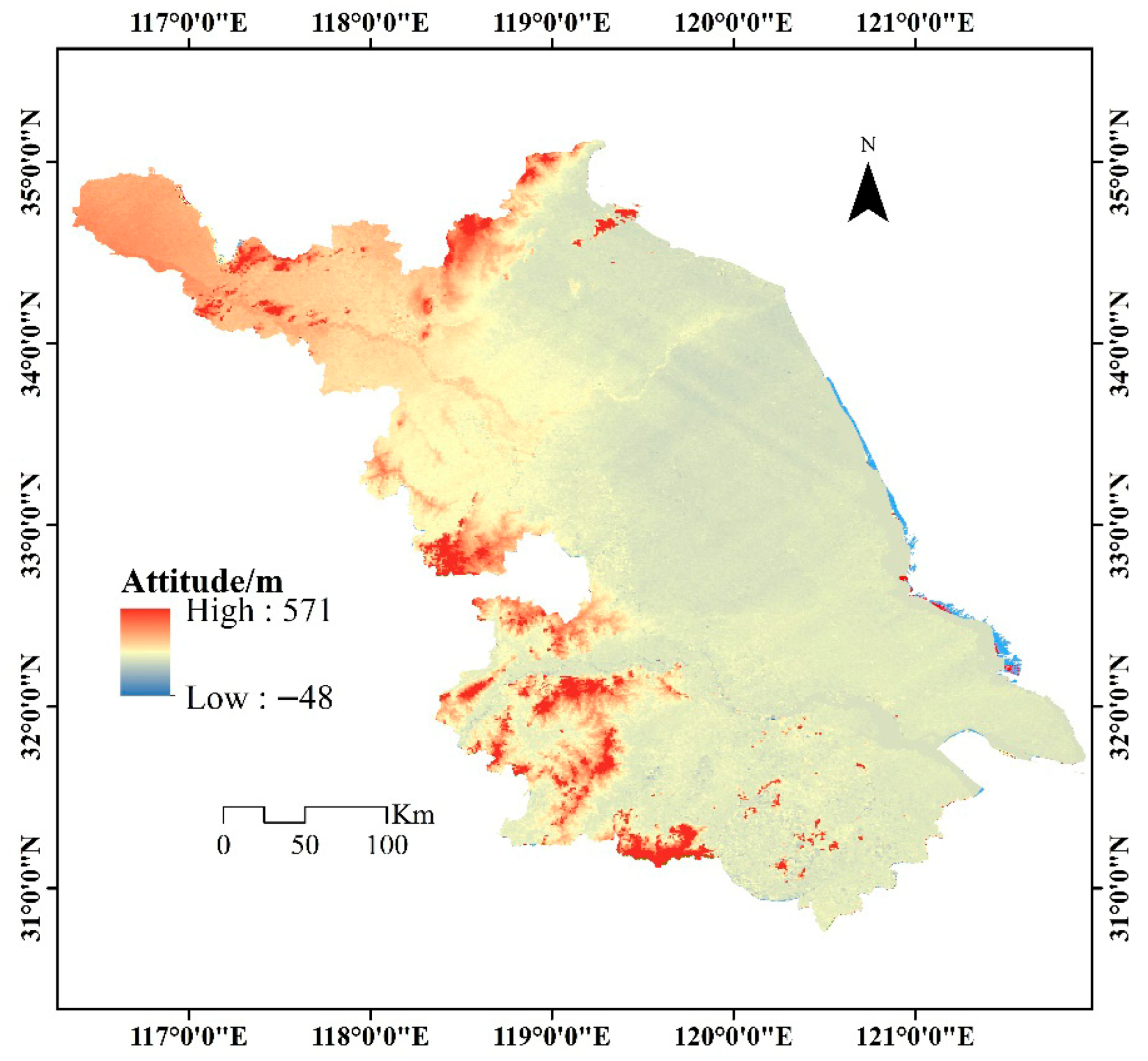

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source and Processing

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Carbon Emission Calculation

2.3.2. Carbon Storage Assessment

2.3.3. Carbon Neutrality Index

2.3.4. Spatial Conflict Measurement Model

- (1)

- Complexity Index (CI)

- (2)

- Spatial Vulnerability Index (FI)

- (3)

- Space Stability Index (SI)

2.3.5. Markov-PLUS Model and Multi-Scenario Settings

- (1)

- Factors Driving Land-Use Change

- (2)

- Scenario Setting

- (3)

- Transfer Matrix

- (4)

- Domain weights

- (5)

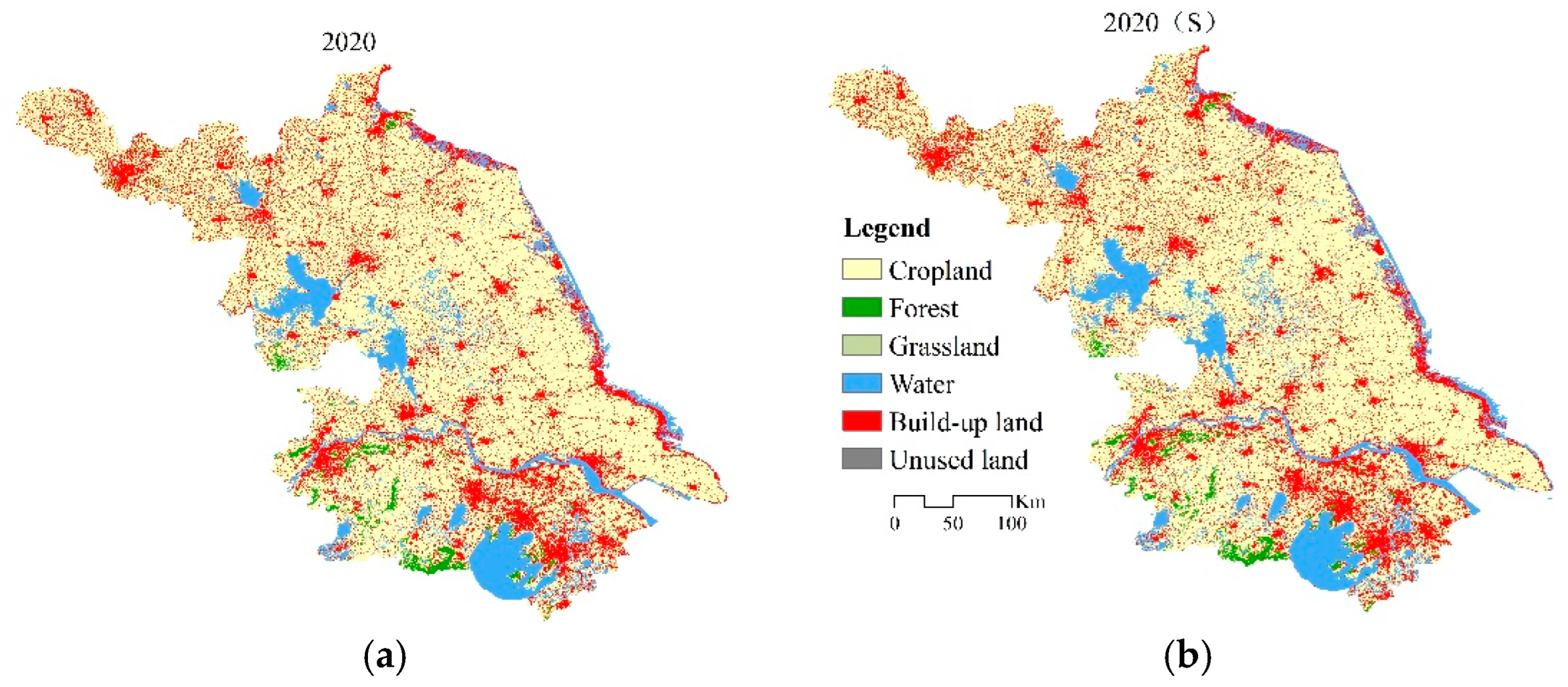

- Accuracy Verification

3. Results

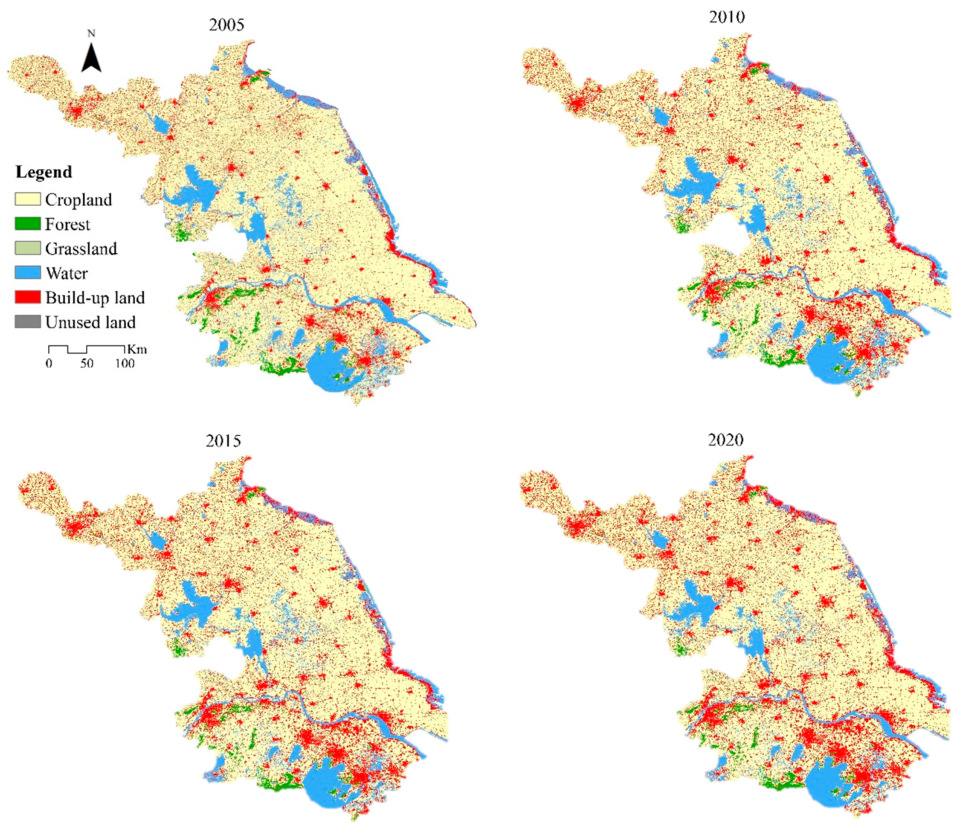

3.1. Characteristics of Territorial Spatial Change

3.1.1. Spatio-Temporal Variations in the Utilization of Territorial Space

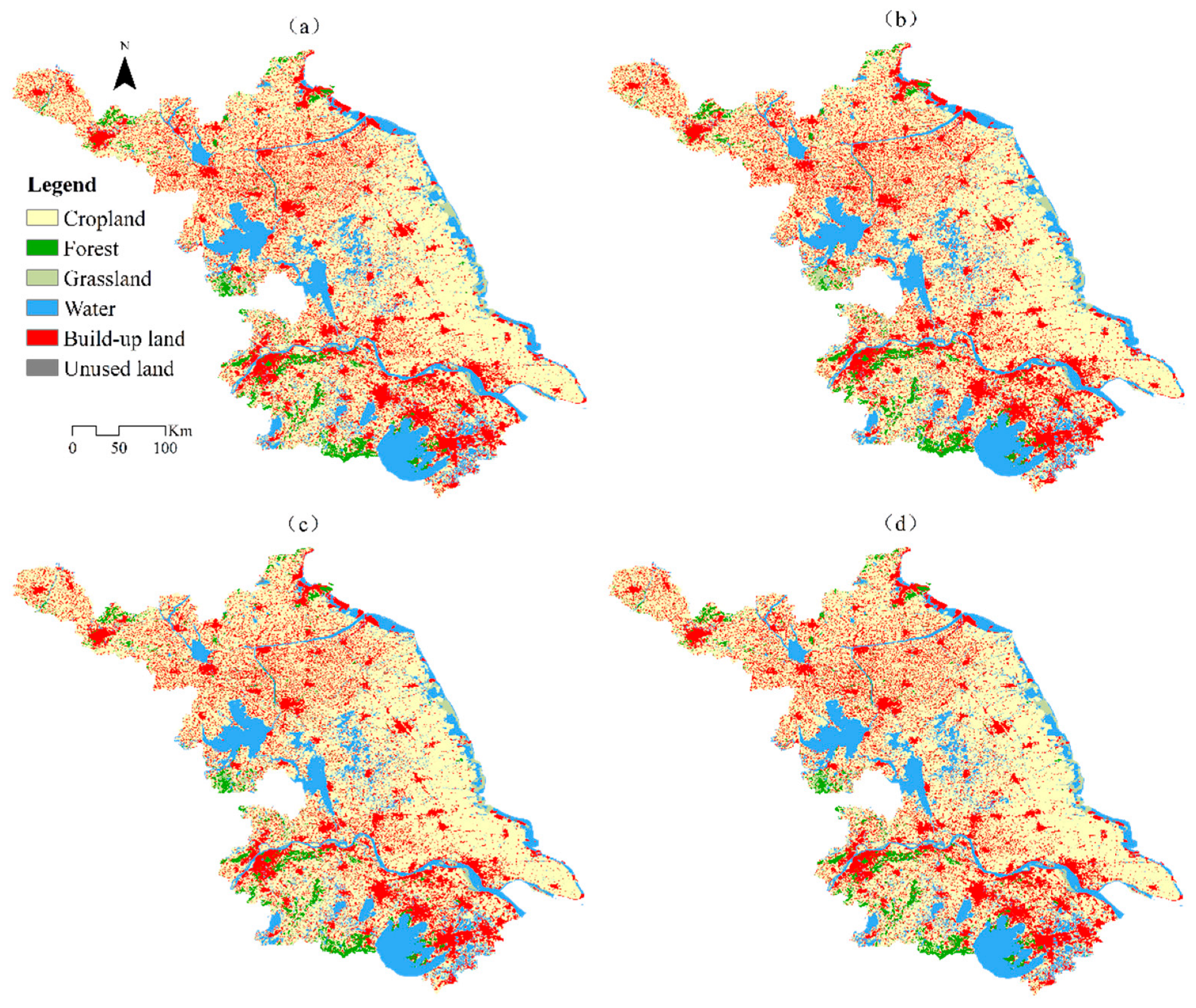

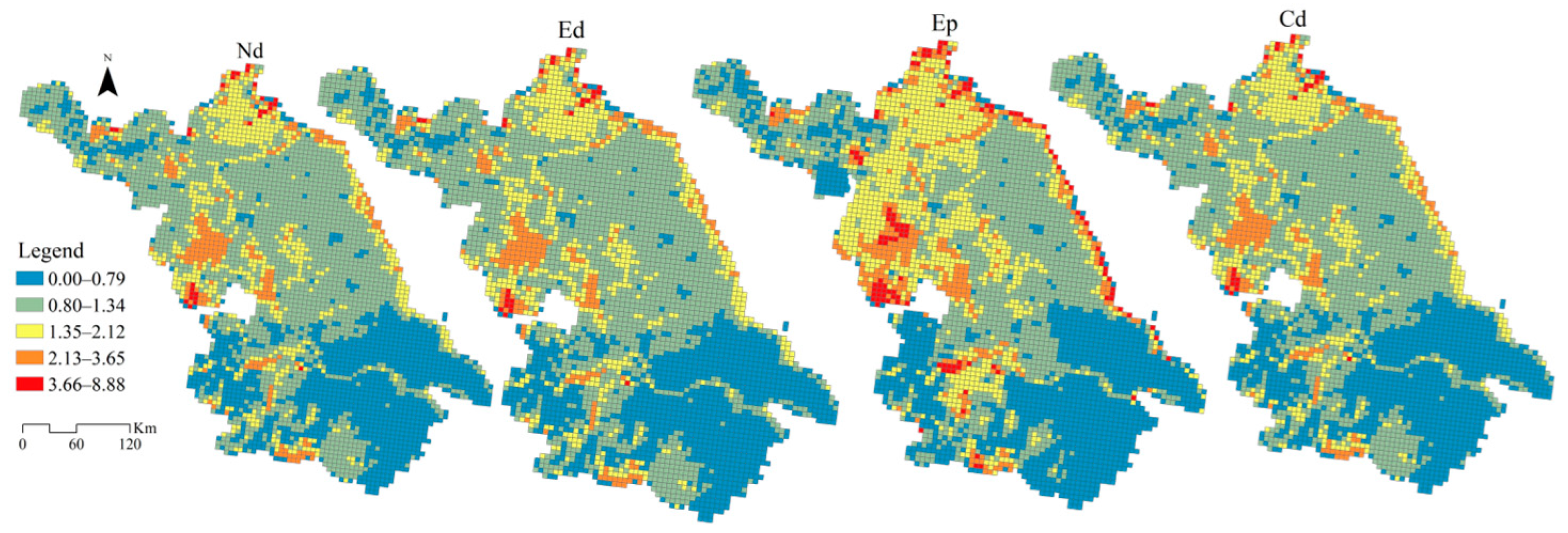

3.1.2. Multi-Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Utilization

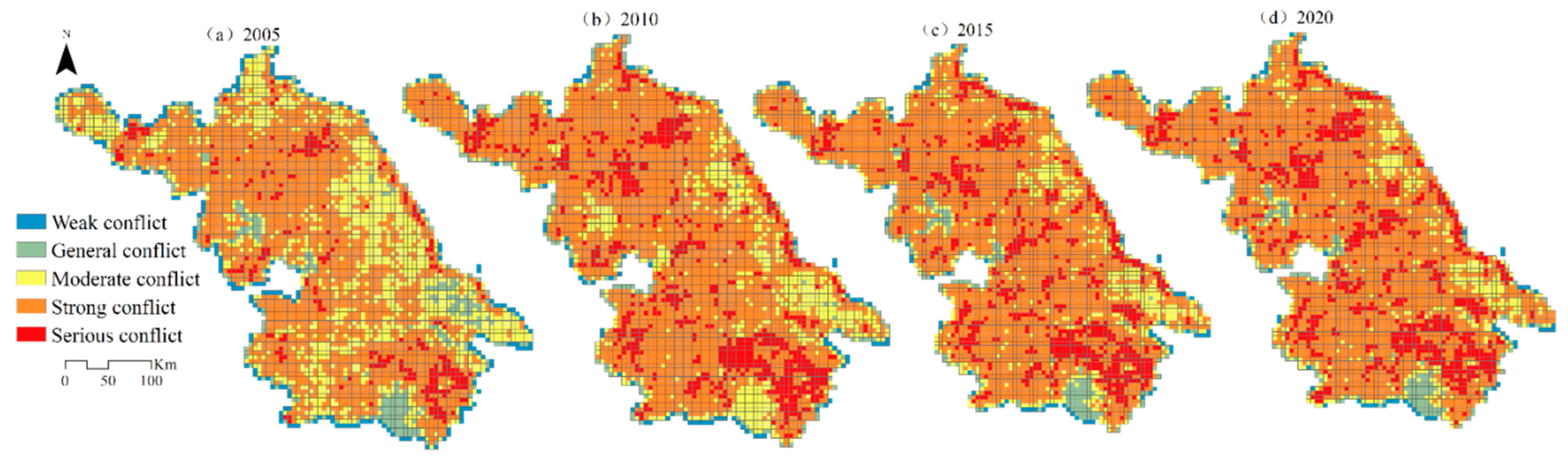

3.2. The Spatio-Temporal Evolution Characteristics of TSCs

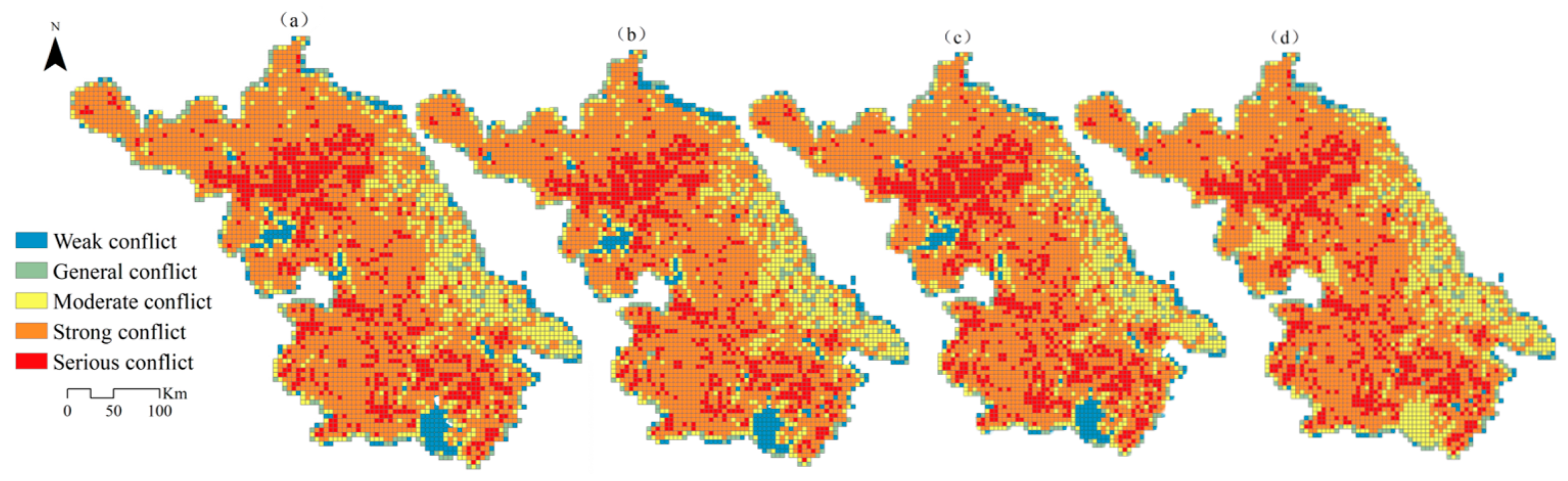

3.3. Multi-Scenario Simulation of TSCs

3.4. Evaluation of the CNI and the Effect of Spatial Conflict Resolution Under Different Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Mechanism Analysis

4.2. Main Application and Reflection of the Research Results

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, J.; Li, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Li, F.; et al. The Impact of Extreme Climate on Soil Organic Carbon in China. Geogr. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; He, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Qi, Y.; Liang, X. Challenges and Opportunities for Carbon Neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 3, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, X. Investigation of a Coupling Model of Coordination between Urbanization and the Environment. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 98, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Land Use Conflict Identification and Sustainable Development Scenario Simulation on China’s Southeast Coast. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-Q.; Wu, D.-F.; Lin, J.-Y.; Pan, Y.-L.; Zhou, P. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Changes in Cropland Occupation and Supplementation Area in the Pearl River Delta and Their Impacts on Carbon Storage. Land 2024, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Reenberg, A.; Boone, C.G.; Fragkias, M.; Haase, D.; Langanke, T.; Marcotullio, P.; Munroe, D.K.; Olah, B.; Simon, D. Urban Land Teleconnections and Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7687–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global Change and the Ecology of Cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Afla, M.R.B.M. Evaluation of Urban Ecological Benefits Utilizing Vegetated Areas Metrics in Nanjing, China. Geocarto Int. 2024, 39, 2395321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Ou, J. Temporal-Spatial Variation and Regulatory Mechanism of Carbon Budgets in Territorial Space through the Lens of Carbon Balance: A Case of the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River Urban Agglomerations, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhao, B.; Lu, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z. Spatially Explicit Carbon Emissions from Land Use Change: Dynamics and Scenario Simulation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Land Use Policy 2025, 150, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Jiang, D.; Fu, J.; Cao, C.; Zhang, D. Spatial Conflict of Production–Living–Ecological Space and Sustainable-Development Scenario Simulation in Yangtze River Delta Agglomerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Multi-Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Carbon Sink Conflicts in the Sichuan-Yunnan Ecological Barrier Region, China. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Tang, J.; Huang, F. The Impact of Industrial Structure Adjustment on the Spatial Industrial Linkage of Carbon Emission: From the Perspective of Climate Change Mitigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Cao, W.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J. Multi-Scenario Land Use Prediction and Layout Optimization in Nanjing Metropolitan Area Based on the PLUS Model. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 1415–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Dong, H.; Zhang, L.; He, S. Spatial-Temporal Change Analysis and Multi-Scenario Simulation Prediction of Land-Use Carbon Emissions in the Wuhan Urban Agglomeration, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Zhang, S.; Deng, W.; Peng, L.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, H. Identification and Analysis of Territorial Spatial Utilization Conflicts in Yibin Based on Multidimensional Perspective. Land 2023, 12, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Liu, J.; Yin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, W.; Tan, W.; Fei, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Ecological Security and Structural Optimization of Land Space in the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration: An Approach Based on the Footprint Family. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, W. Spatial Optimization of Land Use and Carbon Storage Prediction in Urban Agglomerations under Climate Change: Different Scenarios and Multiscale Perspectives of CMIP6. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 116, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Jin, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.; Hu, H.; Du, X.; Zhou, Y. Differentiated Landscape Pattern Transformation Strategies Drive Territorial Space Carbon Neutrality: A Path Exploration Based on Mixed Land Use Units. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 133, 106865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Ren, C.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, W.; Liu, R. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Carbon Emissions in the Pearl River Basin, China: From the Perspective of Land Use and Biomass Burning. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 5876–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.; Wang, Z.; He, X. Effect of Land Use Change on Carbon Emission in Dongting Lake Region. Ecol. Sci. 2023, 42, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhao, X. Simulation of construction land expansion and carbon emission response analysis of Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan Urban Agglomeration based on Markov-PLUS model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Nan, L. Temporal-spatial variance of carbon emission effect in Shaanxi’s land use. Resour. Ind. 2012, 14, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Ding, J.; Rao, J.; Xiang, Y.; Ge, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z. Spatiotemporal Analysis of AGB and BGB in China: Responses to Climate Change under SSP Scenarios. Geosci. Front. 2025, 16, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, J.; Zhu, C.; Wang, J.; Ge, X.; Li, X.; Han, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Historical and Future Variation of Soil Organic Carbon in China. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Que, H. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity and driving forces of carbon storage in the Dongting Lake Basin. China Environ. Sci. 2024, 44, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X. Regional Eco-Risk Analysis of Based on Landscape Structure and Spatial Statistics. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2008, 28, 5020–5026. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Xiu, C.; Gao, Y. Research on Land-Use Conflicts and Risk Zoning in Shenyang, China, Based on Landscape Patterns. J. Urban Plan. Dev 2025, 151, 05025040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. Impacts of Future Land Use Changes on Land Use Conflicts Based on Multiple Scenarios in the Central Mountain Region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cai, H. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Land Use Conflicts and Their Key Influencing Factors in the Changjiang River Basin. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2024, 40, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Jia, Z. Analysis on Absolute Conflict and Relative Conflict of Land Use in Xining Metropolitan Area under Different Scenarios in 2030 by PLUS and PFCI. Cities 2023, 137, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Ou, Y. Measurement and multi-scenario simulation of land use spatial conflicts in Xiangjiang River Basin under carbon neutrality. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 11386–11400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.; Liu, F. Land use optimization and conflict in the central Yunnan urban agglomeration from the perspective of construction control. Prog. Geogr. 2025, 44, 993–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q. Identification of Land Use Conflict Based on Multi-Scenario Simulation-Taking the Central Yunnan Urban Agglomeration as an Example. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Tong, D.; Liu, Z.; Yin, L.; Zheng, W. Forecasting Urban Land Use Change Based on Cellular Automata and the PLUS Model. Land 2022, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Simplified Approach to Estimate Lorenz Number Using Experimental Seebeck Coefficient for Non-Parabolic Band. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 105216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Land-Use Optimization Based on Ecological Security Pattern-A Case Study of Baicheng, Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Geng, Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Relationship between Construction Land Expansion and Territorial Space Conflicts at the County Level in Jiangsu Province. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mamitimin, Y.; Nuerla, A. Identification and Prediction of Land Use Spatial Conflicts in Urban Agglomeration on the Northern Slope of Tianshan Mountains Under the Background of Urbanization. Land 2025, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, X.; Yuan, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D. An Integrated Land Use-Carbon Modeling Framework for Net Carbon Emissions and Spatial Optimization in Northeast China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, S.; Zou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y. Multi-Scenario Simulation of Land Use Spatial Conflicts: A Spatially Explicit Model Integrating Conflict Risk and Ecological Impact. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Xia, B.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, G. Spatio-Temporal Differentiation and Driving Factors of County-Level Food Security in the Yellow River Basin: A Case Study of Ningxia, China. Land 2024, 13, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ye, C.; Tao, H.; Zou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, S. Integrating Future Multi-Scenarios to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Ecological Restoration: A Case Study of the Yellow River Basin. Land 2024, 13, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Qin, B.; Lin, Y. Assessment of the Impact of Land Use Change on Spatial Differentiation of Landscape and Ecosystem Service Values in the Case of Study the Pearl River Delta in China. Land 2021, 10, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, G.; Tao, Z.; Liang, M. Territorial Spatial Planning for Regional High-Quality Development-An Analytical Framework for the Identification, Mediation and Transmission of Potential Land Utilization Conflicts in the Yellow River Delta. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Tian, G.; He, Y.; Wang, M. Spatial and Temporal Differentiation and Coupling Analysis of Land Use Change and Ecosystem Service Value in Jiangsu Province. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zong, R.; Fang, N. Soil Erosion Under Climate and Land Use Changes in China: Incorporating Ecological Policy Constraints. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, S.; Kienmoser, D. Land Use Scenarios for the Development of a Carbon-Neutral Energy Supply-A Case Study from Southern Germany. Land Use Policy 2024, 142, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekar, P.; Mallick, S.P.; Bhattarai, B.; McNamara, P.J.; Downing, L.; Sabba, F. Operational Implications of Low Dissolved Oxygen in Water Resource Recovery Facilities: A Simulation Study on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Carbon Footprint Reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 535, 146891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharizadehshirazi, E.; Roesch, C. A Novel Socio-Techno-Environmental GIS Approach to Assess the Contribution of Ground-Mounted Photovoltaics to Achieve Climate Neutrality in Germany. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, E.; Song, C.; Hong, M.; Jo, H.-W.; Lee, W.-K. How to Manage Land Use Conflict between Ecosystem and Sustainable Energy for Low Carbon Transition?: Net Present Value Analysis for Ecosystem Service and Energy Supply. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1044928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Land use data | Land use data | Chinese Academy of Sciences Resource and Environmental Sciences and Data Center (https://www.resdc.cn/Default.aspx) |

| Socioeconomic factors | Density of population | Chinese Academy of Sciences Resource and Environmental Sciences and Data Center |

| GDP | ||

| Night lighting | Harvard dataverse (https://data.harvard.edu/dataverse (accessed on 6 January 2026)) | |

| Distance factor | Distance from the highway | Open Street Map (https://osgeo.cn/map/) |

| Distance from the first-class road | ||

| Distance from the secondary road | ||

| Distance to the river | ||

| Distance from the railway | ||

| Distance from the city government | National Basic Geographic Information Center (https://www.ngcc.cn/) | |

| Distance from the county government | ||

| Natural factor | Soil erosion | Chinese Academy of Sciences Resource and Environmental Sciences and Data Center |

| DEM | ||

| Aspect | Generated by DEM | |

| Slope gradient | ||

| Annual mean temperature | National Earth System Science Data Center | |

| Annual precipitation |

| Land Use Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropland | 4.75 | 0.745 | 33.51 | 0 |

| Forest | 49.60 | 24.97 | 128.67 | 1.99 |

| Grassland | 20.38 | 15.59 | 48.29 | 18.74 |

| Water | 2.45 | 0.62 | 80.11 | 0.10 |

| Build-up land | 4.83 | 2.17 | 6.37 | 0.58 |

| Unused land | 1.83 | 0.01 | 11.53 | 0.01 |

| Type | Cropland | Forest | Grassland | Water | Build-Up Land | Unused Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural development | 6,084,879 | 294,214 | 129,669 | 1,537,924 | 2,260,946 | 9336 |

| Ecological protection | 6,176,749 | 297,818 | 131,173 | 1,539,105 | 2,162,763 | 9362 |

| Economic priority | 6,023,744 | 292,703 | 129,055 | 1,537,228 | 2,324,922 | 9318 |

| Low-carbon development | 6,146,222 | 296,395 | 130,632 | 1,541,126 | 2,193,237 | 9358 |

| 2020–2030 | Natural Development Scenario | Economic Priority Scenario | Ecological Protection Scenario | Low-Carbon Development Scenario | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | a | b | c | d | e | f | a | b | c | d | e | f | a | b | c | d | e | f | |

| a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| e | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| f | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Type | Cropland | Forest | Grassland | Water | Build-Up Land | Unused Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural development | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.61 |

| Ecological protection | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.01 | 0.60 |

| Economic priority | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.53 |

| Low-carbon development | 0.94 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.67 |

| Year | Cropland | Forest | Grassland | Water | Build-Up Land | Unused Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 73.12 | 1.87 | 0.03 | 13.06 | 11.93 | 0.003 |

| 2010 | 70.99 | 1.81 | 0.04 | 12.96 | 14.19 | 0.003 |

| 2015 | 68.58 | 1.63 | 0.01 | 12.64 | 17.13 | 0.002 |

| 2020 | 68.27 | 1.57 | 0.00 | 11.62 | 18.53 | 0.001 |

| Land Use Type/104 ha | Status in 2020 | Territorial Spatial Structure Under Different Scenarios in 2030 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Ed | Ep | Cd | ||

| Cropland | 624.762 | 608.488 | 602.374 | 617.675 | 614.622 |

| Forest | 30.662 | 29.421 | 29.270 | 29.782 | 29.640 |

| Grassland | 10.634 | 12.628 | 12.668 | 12.884 | 12.766 |

| Water | 149.282 | 153.792 | 153.723 | 153.911 | 154.113 |

| Build-up land | 215.098 | 226.095 | 232.492 | 216.276 | 219.324 |

| Unused land | 1.258 | 1.273 | 1.170 | 1.169 | 1.233 |

| Conflict Level | Threshold Interval | Space Unit Percentage/% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | ||

| Weak conflict | 0–0.2 | 4.79 | 1.68 | 1.32 | 1.18 |

| General conflict | 0.2–0.4 | 7.01 | 3.38 | 5.31 | 5.34 |

| Moderate conflict | 0.4–0.6 | 29.00 | 15.75 | 12.99 | 11.76 |

| Strong conflict | 0.6–0.8 | 53.05 | 62.45 | 62.94 | 62.85 |

| Serious conflict | 0.8–1 | 6.15 | 16.73 | 17.44 | 18.87 |

| Conflict Level | Threshold Interval | Space Unit Percentage/% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Ed | Ep | Cd | ||

| Weak conflict | 0–0.2 | 4.42 | 4.49 | 5.10 | 1.56 |

| General conflict | 0.2–0.4 | 5.15 | 4.81 | 5.15 | 5.49 |

| Moderate conflict | 0.4–0.6 | 16.44 | 15.94 | 16.35 | 18.39 |

| Strong conflict | 0.6–0.8 | 55.95 | 54.43 | 56.63 | 54.66 |

| Serious conflict | 0.8–1 | 18.03 | 20.32 | 16.76 | 19.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, T.; Guo, J. Measurement and Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Conflicts Under the Orientation of Carbon Neutrality in Jiangsu Province, China. Land 2026, 15, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010135

Sun T, Guo J. Measurement and Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Conflicts Under the Orientation of Carbon Neutrality in Jiangsu Province, China. Land. 2026; 15(1):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010135

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Tao, and Jie Guo. 2026. "Measurement and Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Conflicts Under the Orientation of Carbon Neutrality in Jiangsu Province, China" Land 15, no. 1: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010135

APA StyleSun, T., & Guo, J. (2026). Measurement and Scenario Simulation of Territorial Space Conflicts Under the Orientation of Carbon Neutrality in Jiangsu Province, China. Land, 15(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010135