Beyond Homogeneous Perception: Classifying Urban Visitors’ Forest-Based Recreation Behavior for Policy Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the latent classes of urban forest visitors based on their perceived forest recreation values?

- (2)

- How do these classes differ in their recreation behaviors, satisfaction levels, and policy demands?

- (3)

- What policy directions can effectively address the diverse needs of each visitor type?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Survey Design and Sampling

2.2.1. Survey Items

2.2.2. Sampling

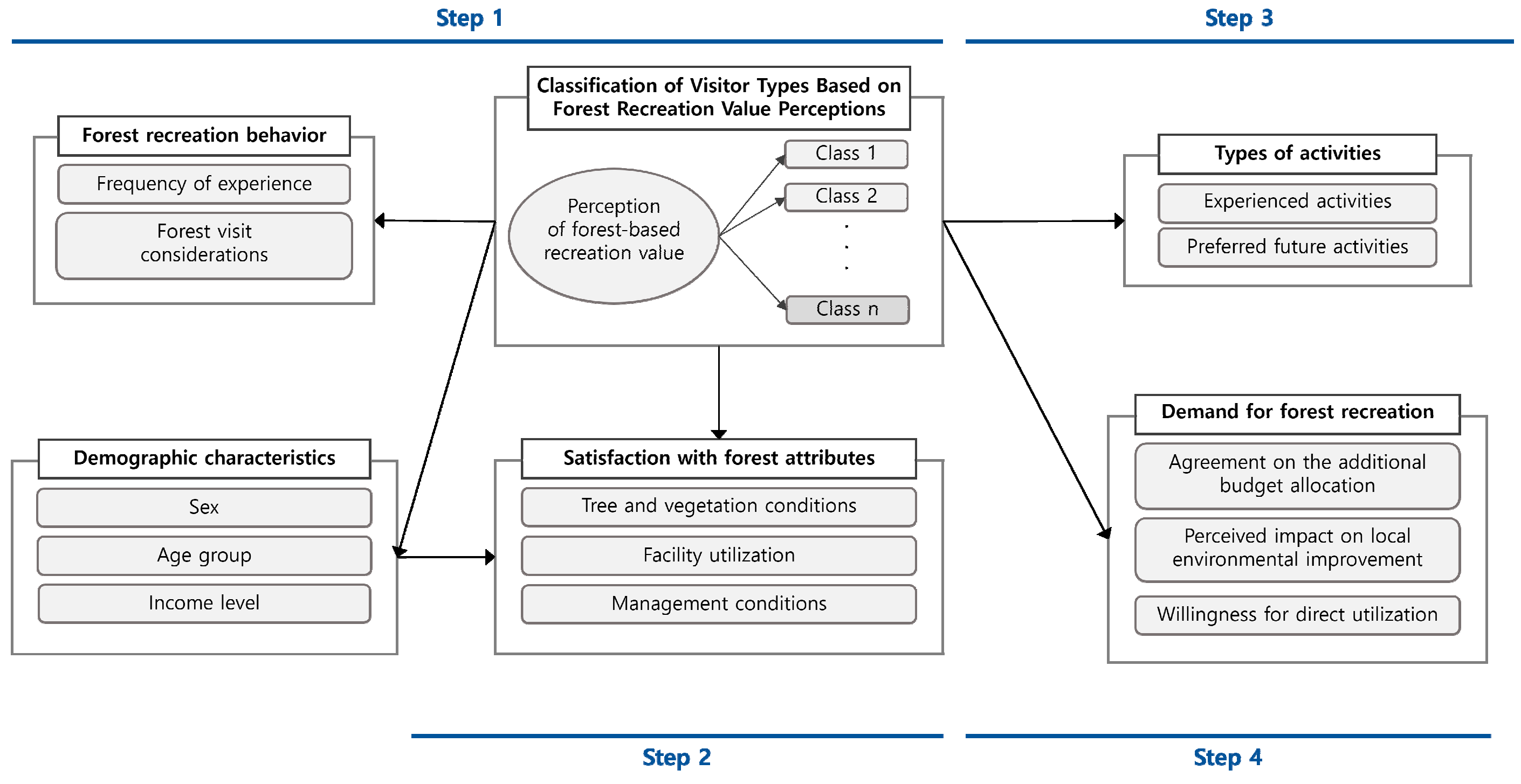

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Classification of Visitor Types Based on FRVPs Using LCA

2.3.2. Forest Satisfaction by Visitor Types and Age

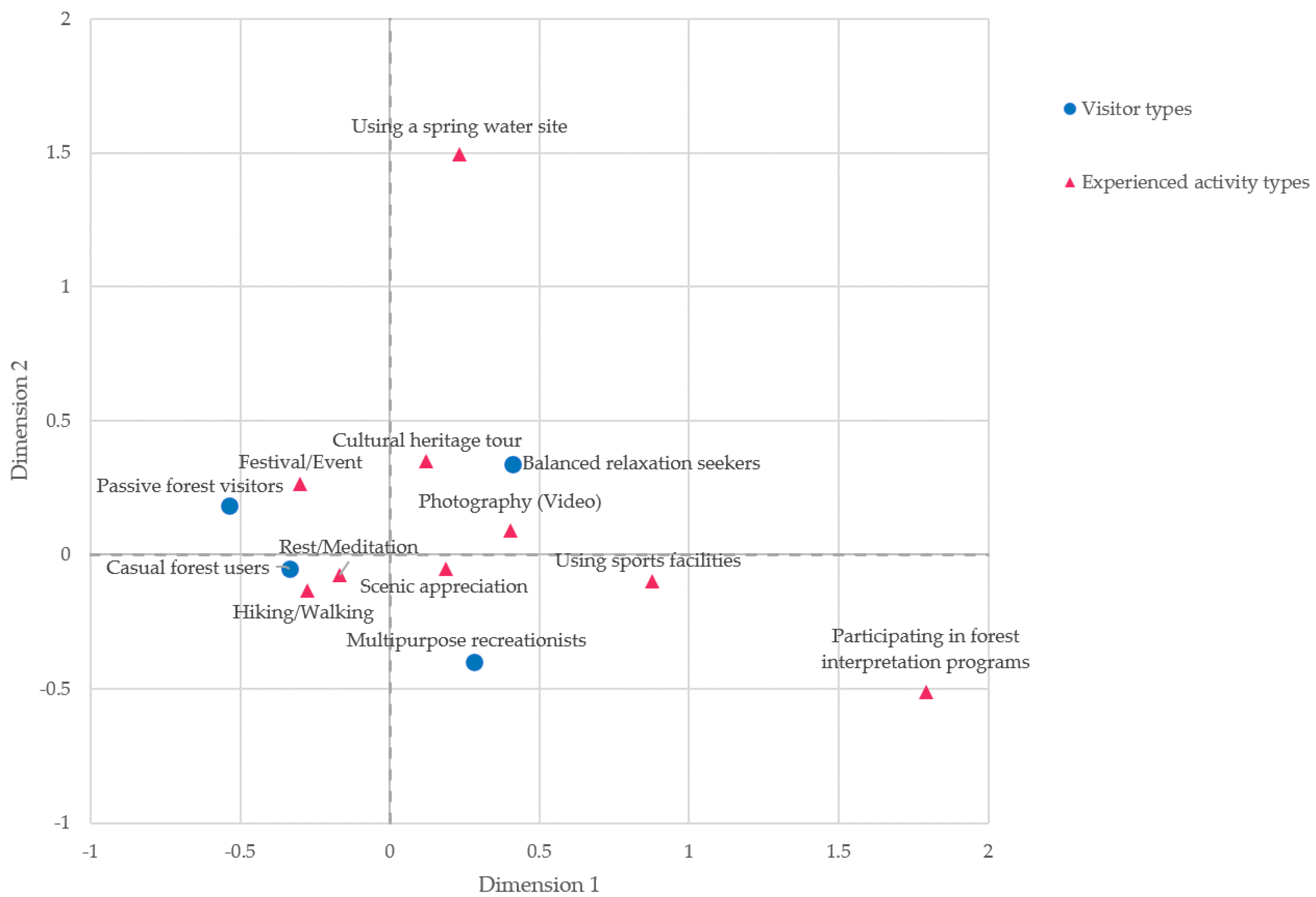

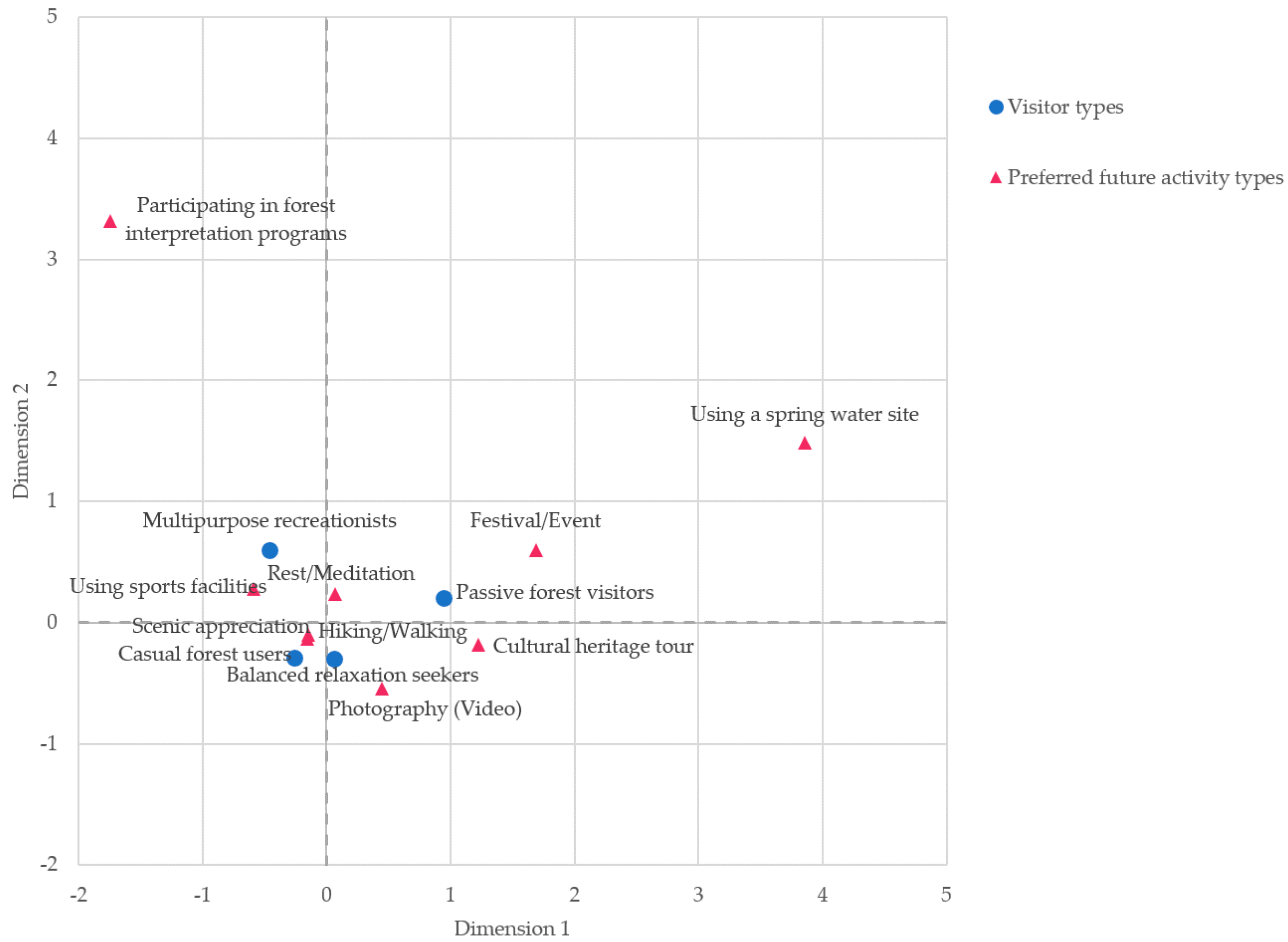

2.3.3. Activity-Preferences Mapping by Visitor Types

2.3.4. Facility Demand and Environmental Improvement Impact by Visitor Types

3. Results

3.1. Classification of Visitor Types Based on FRVPs

3.1.1. Results of the FRVP Survey

3.1.2. Determination of the Optimal Number of Latent Classes

3.1.3. Characteristics of Latent Classes

3.2. Differences in Satisfaction with Forest Attributes by Visitor Type and Age Group

3.3. Analysis of the Relationships Among Visitor Types, Activity Participation, and Future Activity Preferences

3.4. Facility Demand and Environmental Improvement Impact by Visitor Type

4. Discussion

4.1. Forest Recreation Visitor Typologies and Their Interpretative Characteristics

4.2. Perceptual and Behavioral Differences Among Visitor Types

4.3. Implications for Urban Forest Management and Well-Being Promotion

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCA | Latent class analysis |

| FRVP | Forest recreation value perception |

| poLCA | Polytomous variable LCA |

| IC | Information criteria |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| SABIC | Sample-size-adjusted BIC |

| LMR-LRT | Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test |

| BLRT | Bootstrap likelihood ratio test |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CA | Correspondence analysis |

References

- Tyrväinen, L. Economic valuation of urban forest benefits in Finland. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 62, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.E.; Choi, G.E.; Yun, Y.J. An analysis of visitor behaviors and satisfaction in urban forests: Focused on major forests in Incheon. J. People Plants Environ. 2024, 27, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Giessen, L.; Winkel, G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. Forest Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordh, H.; Alalouch, C.; Hartig, T. Assessing restorative components of small urban parks using conjoint methodology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z.; Bao, Z. Landscape perception and recreation needs in urban green space in Fuyang, Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, Y.; Song, K.; Chon, J.; Choi, Y.E. From Landscape Architecture to Nature-Based Solutions: A Strategic Approach to Fine Dust Mitigation in Urban School Forests. Land 2025, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Lin, B.B.; Gaston, K.J.; Bush, R.; Fuller, R.A. What is the role of trees and remnant vegetation in attracting people to urban parks? Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Eder, R. The influence of age on recreational trail preferences of urban green-space visitors: A discrete choice experiment with digitally calibrated images. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Fuller, R.A.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Shanahan, D.F. Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japelj, A.; Mavsar, R.; Hodges, D.; Kovač, M.; Juvančič, L. Latent preferences of residents regarding an urban forest recreation setting in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Forest Policy Econ. 2016, 71, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, I.J.; Gergel, S.E.; Bennett, E.M. Seeing the forest for its multiple ecosystem services: Indicators for cultural services in heterogeneous forests. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Strohbach, M.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J. Urban green space availability in European cities. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.Y.; Heo, S.Y.; Koo, J. Market segmentation to identify forest recreation welfare consumers. J. Korean Soc. Forest Sci. 2023, 112, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Andrada, R.; Pierskalla, C. Visitors’ and residents’ perceptions of urban forests for leisure in Washington DC. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Recreation–amenity use and contingent valuation of urban greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.C.; Park, M.S.; Youn, Y.C. Preferences of urban dwellers on urban forest recreational services in South Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incheon Metropolitan City. 2025 Incheon Urban Master Plan Amendment Main Report; Incheon Metropolitan City: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2012; p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Incheon Metropolitan City. Incheon Metropolitan City’s 2nd Urban Forestry Management Plan (2019–2028); Incheon Metropolitan City: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Incheon Metropolitan City. 2040 Incheon Metropolitan City Park and Green Space Master Plan; Incheon Metropolitan City: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, J.C.; Seok, H.; Byeon, S. Policy Tasks for Improving Demand—Supply Conditions of Forest Recreation Infrastructure; Report of Korea Rural Economic Institute; Korea Rural Economic Institute: Naju, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Service. 2022 National Awareness Survey on Hiking and Forest Trail Experiences; Korea Forest Service Report; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Welfare Institute. 2022 Forest Recreation and Welfare Activity Survey; Korea Forest Welfare Institute Report; Korea Forest Welfare Institute: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Abdul Aziz, F.; Song, M.; Zhang, H.; Ujang, N.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, Z. Evaluating visitor usage and safety perception experiences in national forest parks. Land 2024, 13, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernath, K.; Roschewitz, A. Recreational benefits of urban forests: Explaining visitors’ willingness to pay in the context of the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 89, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Enhancing forest utilization and quality of life: An integrated approach to promoting forest activities. Forests 2024, 15, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, A.R.; Haight, R.G. Public policy for management of forest pests within an ownership mosaic. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 234, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Ward Thompson, C.W. Associations between characteristics of neighbourhood open space and older people’s walking. Urban For. Urban Green. 2008, 7, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Huang, C. Factors affecting the use of urban green spaces for physical activities: Views of young urban residents in Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 17, pp. 161–190. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ Model. Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, R.D.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Engel, S.G.; Simonich, H.; Smyth, J.; Mitchell, J.E. Daily mood patterns and bulimic behaviors in the natural environment. Behav. Res. Ther. 2009, 47, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L.K. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, G.Y.; Park, T.Y. A longitudinal study on the changes in the typology of social relationships among retirees by using latent class analysis. Korean J. Fam. Welf. 2013, 18, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Wickrama, K.A. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 2008, 2, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, H.I.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, L.; Carroll, R.J.; Wu, G. Rapid publication-ready MS-Word tables for two-way ANOVA. Springer Plus 2015, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Kang, B.H.; Lee, E.J.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, J.H. Analysis of the Relationship Between User Characteristics and Forest Welfare Facilities: Focusing on Correspondence Analysis. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2024, 113, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A.; Eperjesi, F.; Gilmartin, B. The application of analysis of variance (ANOVA) to different experimental designs in optometry. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2002, 22, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing means of more than two groups. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2014, 39, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Shon, J.-H. Quality of life depending on the presence of diabetes and engagement in moderate physical activity: Data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2019–2021). Korea J. Sports Sci. 2024, 33, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S. Differences in environmental perception and satisfaction factor of park between young adults and old adults. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2020, 29, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yoo, R.H.; Lee, J.W. Analysis on visitors of healing forest for improvement of forest healing program. J. Korean Forest Recreat. 2016, 20, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Nordlund, A.; Olsson, O.; Westin, K. Beliefs about urban fringe forests among urban residents in Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filkobski, I.; Rofè, Y.; Tal, A. Community gardens in Israel: Characteristics and perceived functions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 17, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.K.; Myeong, J.Y.; Lee, Y.; Choi, Y.E.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Byun, C. Are you okay with overtourism in forests? Path between crowding perception, satisfaction, and management action of trail visitors in South Korea. Forest Policy Econ. 2024, 161, 103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Schipperijn, J.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Use of Small Public Urban Green Spaces (SPUGS). Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.S.; Yoo, R.H.; Lee, J.H. The characteristics of forest leisure activities and demographic factors influencing visitor preference. J. Korean Soc. Forest Sci. 2020, 109, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W. Analysis of forest welfare service users’ activity experience, awareness, and satisfaction: Differences by year and user characteristics. J. Korean Forest Recreat. 2024, 28, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, B.C.; Park, K.H. Determination of motivating factors of urban forest visitors through latent dirichlet allocation topic modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Grahn, P. Stressed individuals’ preferences for activities and environmental characteristics in green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Baran, P.K.; Wu, C. Spatial distributions and use patterns of user groups in urban forest parks: An examination utilizing GPS tracker. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 35, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodev, Y.; Zhiyanski, M.; Glushkova, M.; Shin, W.S. Forest welfare services-the missing link between forest policy and management in the EU. Forest Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.; Burls, A.; Townsend, M.; Ebden, M. Volunteering in nature as a way of enabling people to reintegrate into society. Perspect. Public Health 2011, 131, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Sub-Items | Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | Sex, age group, income level | Nominal scale | |

| FRVP | Necessary for national health management | 5-Point Likert scale | |

| Preferable for quality family time | |||

| Provides vitality through exercise and recreational activities | |||

| Brings happiness and relaxation in daily life | |||

| Enhances social connections | |||

| Helps in understanding the importance of forest ecosystems | |||

| Forest recreation behavior | Frequency of experience | ① Almost daily ② 3–4 times per week ③ 1–2 times per week ④ 1–2 times per month ⑤ 3–4 times per year ⑥ 1–2 times per year | Nominal scale |

| Forest visit considerations | ①Accessibility ② Cost ③ Forest leisure activities ④ Availability of informational signage ⑤ Natural landscape aesthetics ⑥ Provision of rest areas ⑦ Experience programs | ||

| Types of activities | Experienced activities | ① Hiking/walking ② Scenic appreciation ③ Cultural heritage tour ④ Rest/meditation ⑤ Festival/event ⑥ Photography (Video) ⑦ Using a spring water site ⑧ Using sports facilities ⑨ Participating in forest interpretation programs | Nominal scale |

| Preferred future activities | ① Hiking/walking ② Scenic appreciation ③ Cultural heritage tour ④ Rest/meditation ⑤ Festival/event ⑥ Photography (Video) ⑦ Using a spring water site ⑧ Using sports facilities ⑨ Participating in forest interpretation programs | ||

| Demand for forest recreation | Agreement on additional budget allocation | 5-Point Likert scale | |

| Perceived impact on local environmental improvement | |||

| Willingness for direct utilization | |||

| Satisfaction with forest attributes | Tree and vegetation conditions | 5-Point Likert Scale | |

| Facility utilization | |||

| Management conditions | |||

| Category | Total | Survey Target Areas | Non-Survey Target Areas | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jung-Gu | Seo-Gu | Michuhol-Gu | Yeonsu-Gu | Namdong-Gu | Bupyeong-Gu | Gyeyang-Gu | Dong-Gu | Ganghwa-Gun | Ongjin-Gun | ||

| Population | 2987,918 | 157,595 | 618,052 | 405,471 | 389,722 | 496,318 | 488,383 | 282,826 | 59,940 | 69,162 | 20,449 |

| Proportion (%) | 100.0 | 5.3 | 20.7 | 13.6 | 13.0 | 16.6 | 16.3 | 9.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| Category | Disagree * | Neutral | Agree ** | Mean (SD) *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for health management | 17 (2.5) | 106 (15.1) | 577 (82.4) | 4.23 (0.812) |

| Quality time with family | 26 (3.7) | 140 (20.0) | 534 (76.3) | 4.04 (0.832) |

| Vitality through exercise and leisure | 13 (1.8) | 147 (21.0) | 542 (77.2) | 4.03 (0.765) |

| Happiness and relaxation in daily life | 11 (1.6) | 127 (18.1) | 572 (80.3) | 4.12 (0.775) |

| Active social interactions | 22 (3.2) | 183 (26.1) | 495 (70.7) | 3.95 (0.830) |

| Understanding of forest ecosystem | 17 (2.4) | 149 (21.3) | 534 (76.3) | 4.05 (0.801) |

| Category | Number of Latent Classes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 * | 5 | 6 | ||

| Information criteria (ICs) | AIC | 7929.424 | 7220.555 | 7164.971 | 7124.287 | 7123.511 |

| BIC | 8152.427 | 7557.535 | 7615.528 | 7688.621 | 7801.622 | |

| SABIC | 8030.601 | 7389.888 | 7402.459 | 7429.931 | 7497.3 | |

| Likelihood-based fit index | LMR-LRT | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.041 ** |

| BLRT | 0.600 | 0.500 | 0.933 | 0.733 | 1.000 | |

| Classification accuracy of the model | Entropy | 0.070 | 0.097 | 0.229 | 0.252 | 0.304 |

| Class proportion (%) | Class 1 | 62.000 | 21.000 | 22.000 | 21.000 | 22.000 |

| Class 2 | 38.000 | 31.000 | 21.000 | 22.000 | 1.000 | |

| Class 3 | 48.000 | 37.000 | 4.000 | 31.000 | ||

| Class 4 | 19.000 | 39.000 | 16.000 | |||

| Class 5 | 14.000 | 21.000 | ||||

| Class 6 | 9.000 | |||||

| FRVP | Class 1 (n = 153, 21.8%) | Class 2 (n = 149, 21.3%) | Class 3 (n = 262, 37.4%) | Class 4 (n = 136, 19.5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need for health management | 4.93 (0.306) | 4.11 (0.776) | 3.74 (0.448) | 3.05 (0.636) |

| Quality time with family | 4.91 (0.289) | 4.27 (0.553) | 3.86 (0.437) | 3.10 (0.612) |

| Vitality through exercise and leisure | 5.00 (0.000) | 4.48 (0.565) | 3.95 (0.358) | 3.08 (0.597) |

| Happiness and relaxation in daily life | 4.96 (0.278) | 4.72 (0.480) | 4.09 (0.479) | 3.13 (0.704) |

| Active social interactions | 4.92 (0.315) | 4.41 (0.558) | 3.86 (0.484) | 3.06 (0.593) |

| Understanding of forest ecosystem | 4.92 (0.372) | 4.42 (0.639) | 3.89 (0.404) | 2.95 (0.612) |

| Category | Multipurpose Recreationists | Balanced Relaxation Seekers | Casual Forest Users | Passive Forest Visitors | (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n = 700) | Male | 60 (39.2) | 76 (51.0) | 114 (55.0) | 81 (59.6) | 14.051 (0.003) ** |

| Female | 93 (60.8) | 73 (49.0) | 118 (45.0) | 55 (40.4) | ||

| Age group (n = 700) | 30 or younger | 44 (28.8) | 36 (24.2) | 93 (35.5) | 58 (42.6) | 21.478 (0.002) ** |

| 40–50 | 52 (34.0) | 50 (33.6) | 88 (33.6) | 51 (37.5) | ||

| 60 or older | 57 (37.2) | 63 (42.2) | 81 (30.9) | 27 (19.9) | ||

| Income level * (n = 700) | Below 3106 USD | 61 (39.9) | 61 (40.9) | 102 (38.9) | 61 (44.9) | 5.239 (0.513) |

| 3106–4658 USD | 38 (24.8) | 49 (32.9) | 75 (28.6) | 37 (27.2) | ||

| Above 4658 USD | 54 (35.3) | 39 (26.2) | 85 (32.5) | 38 (27.9) | ||

| Frequency of experience (n = 646) | Almost daily | 3 (2.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 24.190 (0.062) |

| 3–4 times per week | 4 (2.7) | 4 (2.8) | 7 (3.0) | 5 (4.2) | ||

| 1–2 times per week | 24 (16.4) | 16 (11.0) | 28 (11.9) | 16 (13.3) | ||

| 1–2 times per month | 49 (33.6) | 49 (33.8) | 73 (31.0) | 36 (30.0) | ||

| 3–4 times per year | 36 (24.7) | 49 (33.8) | 81 (34.5) | 25 (20.8) | ||

| 1–2 times per year | 30 (20.5) | 26 (17.9) | 46 (19.6) | 38 (31.7) | ||

| Forest visit considerations (n = 646) | Accessibility | 99 (67.8) | 95 (65.5) | 166 (70.6) | 81 (67.5) | 37.730 (0.004) ** |

| Cost | 1 (0.7) | 5 (3.4) | 11 (4.7) | 11 (9.2) | ||

| Availability of informational signage | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (5.0) | ||

| Natural landscape aesthetics | 35 (24.0) | 23 (15.9) | 41 (17.5) | 14 (11.7) | ||

| Provision of rest areas | 10 (6.8) | 17 (11.7) | 13 (5.5) | 6 (5.0) | ||

| Experience programs | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Etc. | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Variable | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree and vegetation conditions | Visitor type (A) | 23.77 | 3 | 7.92 | 13.70 ** |

| Age group (B) | 0.15 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.13 | |

| A × B | 17.12 | 6 | 2.85 | 4.93 ** | |

| Error | 315.08 | 545 | 4.94 | ||

| Facility utilization | Visitor type (A) | 37.10 | 3 | 12.37 | 20.36 ** |

| Age group (B) | 0.69 | 2 | 0.34 | 0.57 | |

| A × B | 14.96 | 6 | 2.49 | 4.11 ** | |

| Error | 330.98 | 545 | 0.61 | ||

| Management conditions | Visitor type (A) | 43.20 | 3 | 14.40 | 24.28 ** |

| Age group (B) | 0.33 | 2 | 0.17 | 0.28 | |

| A × B | 8.67 | 6 | 1.44 | 2.44 * | |

| Error | 323.25 | 545 | 0.59 | ||

| Dependent Variables | Visitor Type | n | Mean | SD | F | p | Post-Hoc Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement on additional budget allocation | a | 153 | 4.59 | 0.64 | 83.519 | <0.001 | d < c < b < a |

| b | 149 | 4.21 | 0.75 | ||||

| c | 262 | 3.89 | 0.73 | ||||

| d | 136 | 3.27 | 0.82 | ||||

| Perceived impact on local environmental improvement | a | 153 | 4.67 | 0.55 | 120.181 | <0.001 | d < c < a, b |

| b | 149 | 4.38 | 0.65 | ||||

| c | 262 | 4.05 | 0.60 | ||||

| d | 136 | 3.29 | 0.70 | ||||

| Willingness for direct utilization | a | 153 | 4.72 | 0.53 | 119.765 | <0.001 | d < c < b < a |

| b | 149 | 4.56 | 0.63 | ||||

| c | 262 | 4.11 | 0.63 | ||||

| d | 136 | 3.38 | 0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yun, Y.-J.; Choi, G.E.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, Y.E. Beyond Homogeneous Perception: Classifying Urban Visitors’ Forest-Based Recreation Behavior for Policy Adaptation. Land 2025, 14, 1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081584

Yun Y-J, Choi GE, Lee J-Y, Choi YE. Beyond Homogeneous Perception: Classifying Urban Visitors’ Forest-Based Recreation Behavior for Policy Adaptation. Land. 2025; 14(8):1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081584

Chicago/Turabian StyleYun, Young-Jo, Ga Eun Choi, Ji-Ye Lee, and Yun Eui Choi. 2025. "Beyond Homogeneous Perception: Classifying Urban Visitors’ Forest-Based Recreation Behavior for Policy Adaptation" Land 14, no. 8: 1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081584

APA StyleYun, Y.-J., Choi, G. E., Lee, J.-Y., & Choi, Y. E. (2025). Beyond Homogeneous Perception: Classifying Urban Visitors’ Forest-Based Recreation Behavior for Policy Adaptation. Land, 14(8), 1584. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081584