“Metropolitan Parks” in Southern Barcelona: Key Nodes at the Intersection of Green Infrastructure and the Polycentric Urban Structure †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Background: Green Spaces and Connectivity in Urban Planning

1.2. Metropolitan Parks: From Green Infrastructure Components to Inclusive Social Catalysts

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Metropolitan Parks

2.2. Scales of Analysis and Research Approaches

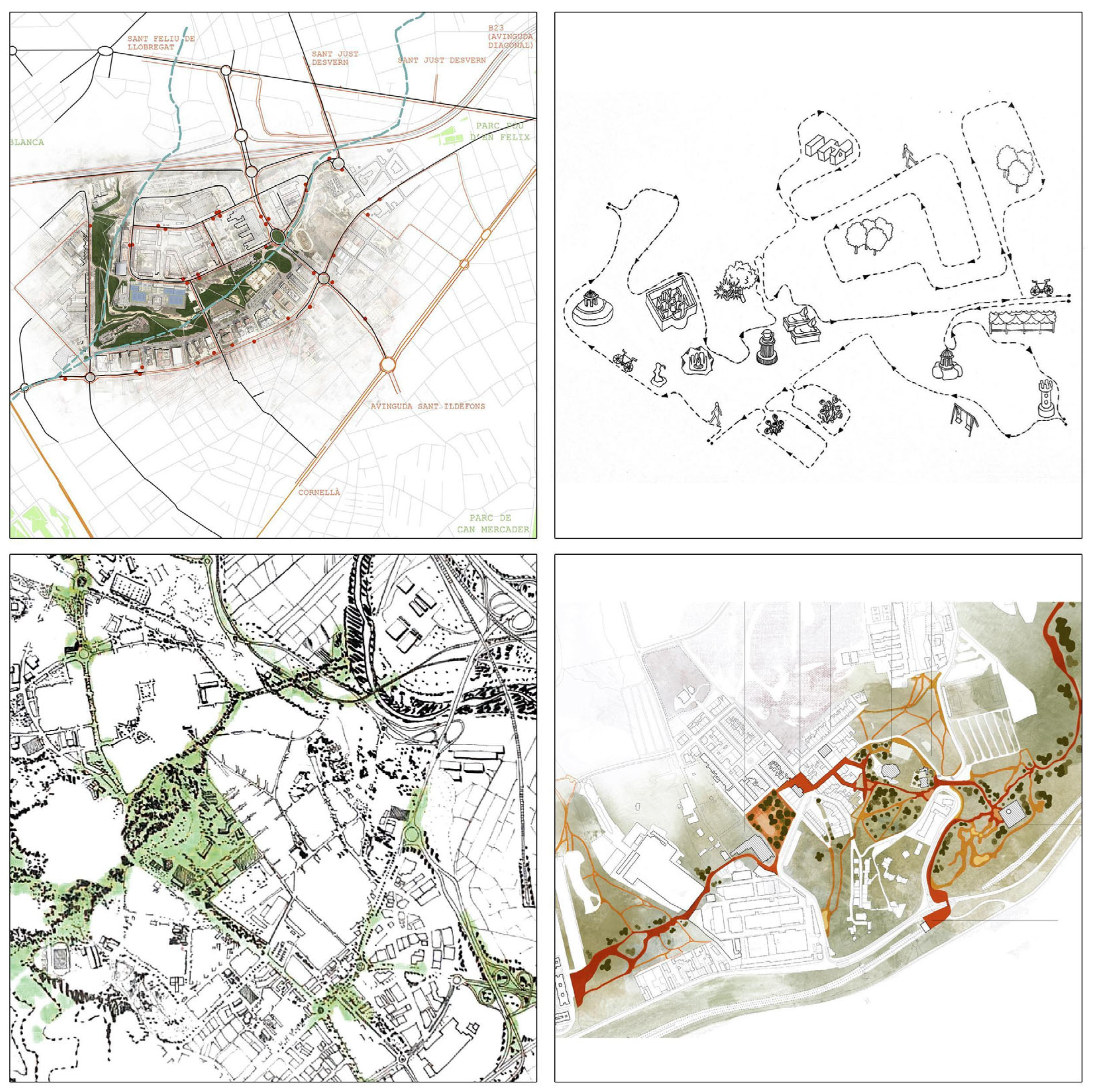

- Territorial Role within Metropolitan Networks, 20 × 20 km scale: This scale allows for an understanding of the park’s position within the metropolis as a whole and, specifically, its relative position concerning the networks that provide its functional support (transport infrastructure, collective communication systems, metropolitan-scale public facilities, etc.). The graphic analysis sources materials from the “Pla territorial metropolità de Barcelona”, selecting a series of rail infrastructures to study based on publicly available CAD data. Furthermore, the basemap has been sourced from the “Cartografia Bàsica AMB”, and has been edited to highlight each of the case study parks, with a table relating travel times from the park to key urban centers with information sourced from Barcelona’s Transport Authority [4].

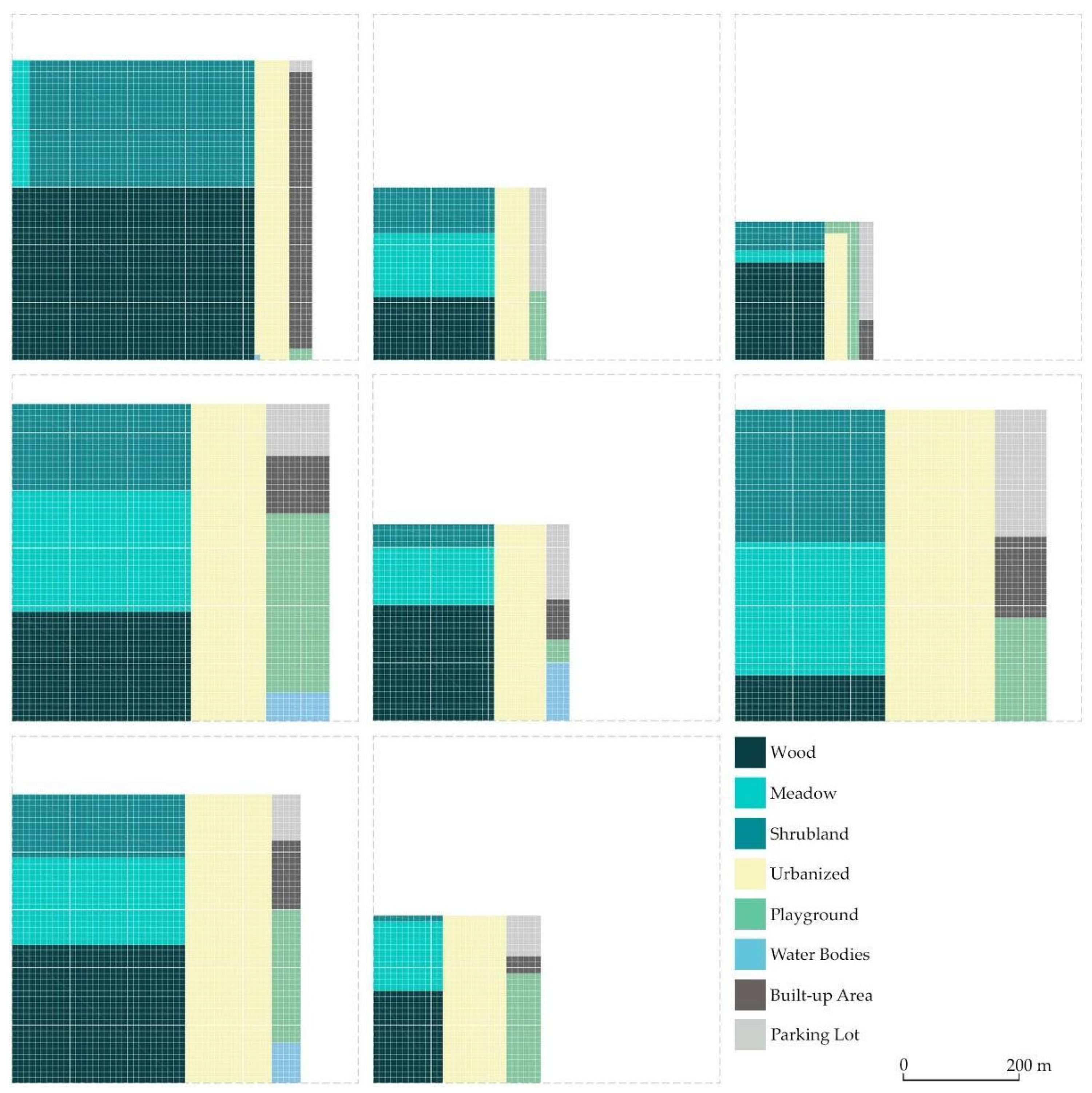

- Land cover and green connectivity, 3 × 3 km scale: This scale relates the park’s public space to the system of nearby metropolitan open spaces, enabling an understanding of the park’s actual or potential contribution to the ecological systems and processes operating within the bio-physical matrix that supports the metropolis. A GIS graphic analysis has been made based on selected layers of the land cover map of the Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya (Barcelona, Spain), as well as data sourced from Barcelona’s Metropolitan Authority AMB. Where data were not covered by AMB’s studies, data were obtained by recreating AMB’s methodology, keeping the values consistent with the study’s original timeframe (2021) so as to establish comparisons between parks. Key parameters of each of the parks are included, indicating the proportion of green within a 3 × 3 km buffer sourced through the aforementioned land cover map and processed with QGIS 3.40. In this regard, the average NDVI value of each of the parks in 2021 was sourced via satellite imagery provided by Sentinel-2 (ESA, Paris, France), and processed using QGIS. The biodiversity level of each the parks was derived via the Shannon index, sourced from a study published by AMB [4]. Finally, an analysis of each of the parks in relation to large green connectors measures the position of these structures via QGIS and land cover data.

- Urban fabric and perimeter definition, 2 × 2 km scale: This scale provides a perspective on the park’s immediate surroundings, examining the urban fabric that encloses the open space and how its particular morphology influences the formal and functional response of different areas within the park. Vector data on build-up areas provided by the Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya were used to relate each of the parks to their surroundings through QGIS in a 2 × 2 km area, alongside population data sourced from census data [48]. Thermoregulation data, sourced from AMB [4], were recreated via satellite data obtained from Landsat (NASA/USGS, Washington, D.C., US, Reston, VA, US) through an LST study comparing the average surface temperature of the park with that of areas surrounding it via QGIS and Google Earth Engine [49]. Finally, individual gross incomes within close proximity of the park have also been sourced from AMB and further completed with census data in regard to Park Three [4,48].

- Park Design, 1 × 1 km scale: This level delves into the park’s composition, examining its layout, components, dimensions, functions, equipment, and overall design. Data obtained from in situ visits have been contrasted with information obtained from high-resolution orthophotos provided by AMB, which have been used as a base to develop a CAD-based graphic study of each of the park’s internal compositions and design elements. The case study parks have been entirely redrawn and measured, classifying each of the surfaces in relation to their surface composition in a series of categories that range from the urban to the natural.

2.3. Case Studies: Eight Parks in the Llobregat Basin

2.3.1. The Western Side of the Llobregat River Basin

- Pi Gros (1)—acts as a potential ecological “bridge” between the Serra de l’Ordal and the Llobregat Basin. Positioned near railway lines, its porous surface—composed of woodland and shrubland—forms part of a broader Green Infrastructure system.

- Can Lluc (2)—located on the outskirts of Santa Coloma de Cervelló, reflects its transitional position. Near the town, it features urban elements like playgrounds and parking, while further out, it shifts into meadows and forested zones, creating a gradient between built and natural environments.

- Cripta Güell (3)—surrounds the renowned Cripta Güell, a heritage site designed by Antoni Gaudí. Although not managed by AMB, it holds cultural significance. The park is characterized by pine trees interspersed with remnants of unused building materials from the church’s original construction.

- La Muntanyeta (4)—presents a dual landscape: its lower area is urbanized, integrating civic buildings like municipal offices, libraries, sports centers, schools, and a swimming pool. Its upper part, defined by rugged topography, consists of shrubs, open meadows, and woodland.

2.3.2. The Eastern Side of the Llobregat River Basin

- Torreblanca (5) is in an urban setting and close-by to the Joan Gamper sporting facilities. It is an amalgam of several green spaces: a nineteenth-century ornamental garden from a private origin, a dense and orderly green canopy, some fields regularly planted with ornamental purposes and two small ponds with adjacent open spaces punctuate the park. Furthermore, the original palace of the historic garden and some new buildings host some public administration offices.

- Fontsanta (6) is a large, highly urban park that is well integrated into the metropolitan fabric. It is adjacent to major facilities like the regional public television station and a large hospital, as well as local community services.

- Can Mercader (7) is divided by steep terrain and rail infrastructure. The southern portion is an ornamental 19th-century park centered around the historic Can Mercader house—now a mathematics museum. The northern section, with its winding paths and meadows, is disconnected and more topographically complex.

- Les Planes (8) lies beside the densely packed Cemetery of Hospitalet and is situated within one of the most densely populated areas in Europe [56]. Its layout is highly structured, segmented into zones for play, sports, leisure, and parking, with actual green space confined to the park’s edges.

3. Results

3.1. Territorial Role Within Metropolitan Networks

- The western margin of the Llobregat presents an almost perfect overlap between suburban rail stations and selected case studies, owing to an often-occurring triple intersect between park–urban center–train station considering the development of this margin through independent townships (a configuration that lends itself well to the aims of the multi-center metropolis envisioned by the future Barcelona PDU Masterplan).

- The eastern side is much more integrated both within the urban fabric and the transportation network, with inter-connected tram, metro and rail lines of different scales.

3.2. Land Cover and Green Connectivity

3.3. Urban Fabric and Perimeter Definition

3.4. Park Design Qualitative Considerations: Urbanization Versus Naturalization

Park Design Quantitative Dimensions

4. Discussion

4.1. Systemic Overview

- Although the location of the parks responds to certain criteria of spatial equity (efforts have been made to avoid concentrating the parks in just a few municipalities, instead seeking spaces for this use throughout the entire geography), their characteristics do make them quite different. The analysis of the parks sample shows that there is no correlation between their location (more central or more peripheral) and their size. Central parks (in denser urban areas) are not smaller than those on the urban edges: a phenomenon that can be explained by the lower demand from nearby populations in the latter, and because in many cases, there is a clear continuity between the park of limited dimension (technically in the limits of “Urban Land”) and the open forest or agricultural spaces (technically in “Non-Building Land”) [5].

- Regarding their contribution to Green Infrastructure, it is confirmed that in all cases, due to their size, the parks are valuable elements at an intermediate scale between the major green systems (river areas, agricultural parks, coastal mountain range, etc.) and urban greenery, which is often relegated to small public spaces (sometimes not very green) and tree-lined streets. This intermediate scale approach contrasts with other Mediterranean approaches, such as in Milan, where the focus seems to be placed on the development of peripherical green structures of a larger size that extend beyond the urban scale [31,36]. Nonetheless, the role of Metropolitan Parks changes depending on their position, either on built or unbuilt areas, and if they are in continuity with regional Green Infrastructures, as the eco-systemic services provided respond to those of inhabitants in close proximity or take on the role of providing important links between natural habitats [44]. To ensure these roles, it can be considered that improving their internal configuration is just as important as the series of coordinated actions that allow their efficient and practical interconnection with the surrounding open spaces of different sizes [43]. In fact, ecology is a key component of the park’s program: as the need to incorporate ecosystemic services linked to the needs of the citizens become imperative, the possibility to serve both local and metropolitan needs is an interesting by-product of this challenge, faced by cities such as Barcelona, which consider parks as part of a network of climate shelters. Ongoing efforts actively aim to incorporate ecological restoration strategies, the creation of evolving and resilient landscapes, specific installations for environmental education, and connectivity requirements that extend beyond the park’s boundaries, among other initiatives, also seen in cities such as Paris and Milan [34,35]. In this way, the activities within the park also trend towards catering to an “active community” that is more participatory and less reliant on structured programming [45,60].

- The view of the parks from their perimeter varies significantly between cases, although they commonly tend to be quite lacking in uniformity. This characteristic has historically influenced the placement of their entrances and will allow for a certain specialization in the distribution of uses within the park, as well as the appropriate placement of new functions in the future. A broader perspective highlights segments of the perimeter that connect with agricultural or forested areas, thereby extending the park’s ecological functions far beyond its boundaries, allowing a “Park of Parks” approach, as seen in Paris [42]. Conversely, several parks have “hard borders” where they border infrastructural elements such as the railway tracks or big road arteries, resulting in a kind of “non-relationship” along those sections and limiting possible continuities.

- In the balancing act between the functions hosted by parks and their degree of urbanization, a certain specialization of spaces stands out—the result of demands from various social groups and a strong commitment to public investment aimed at meeting citizens’ expectations. In any case, the desire to respond to social demands must be balanced with the ecological values of the parks themselves. This tension helps explain recent trends toward greater naturalization of these spaces and growing appreciation for newer design aspects, such as their role as climate refuges, a trend also observed also in other major European cities such as Paris and Brussels [34,61].

4.2. Design Strategies to Scale up Local Parks

- Promoting New Public Buildings and Increasing Attractiveness: A program capable of drawing publics from diverse parts of the city can act as a catalyzer for the park’s transformation, repurposing infra-utilized spaces, such as over-sized car parks and obsolete facilities present in parks like Fontsanta (Park Six) to avoid encroachment on permeable soil. A constellation of “metropolitan facilities” could connect several of these parks also through the services provided.

- Underlying or Intensifying Focal Points: Certain areas of the park can be highlighted as “focal points”, such as its entrances or gathering spaces. The aesthetic quality of an ornamental park that carries a notable amount of history behind it can be enhanced through a new understanding of eco-systemic values, as “climatic shelters” can renew the idea of a self-contained “Eden” as a reference for the whole city. Parks such as Torreblanca (5), Can Mercader (7) and Les Planes (8) could combine their historic past with these new perspectives.

- Scaling up Local Built Heritage: The integration of heritage evidences the interrelation between past and present as a boon for a park, reinforcing values of identity and place, as seen in Colònia Güell (3), a successful example of a park of metropolitan appeal through its appealing heritage value. Furthermore, the creation of post-industrial cultural landscapes is a chance to renew grey infrastructure within the park, as exemplified throughout Europe [31,62].

- Increasing “Porosity” of the Limits: Regarding the surrounding urban fabric and mobility infrastructure, low “porosity” limits are unable to connect separate neighborhoods such as in the case of Can Mercader (7). An opportunity is present considering potential “stretching” of certain key traces, the position of relevant public transportation facilities and the park’s relation with the diverse fabrics in its vicinity.

- Strengthening “Green Infrastructure”, taking into consideration the network recently designed in the drafting of the new Metropolitan Master Plan [2].

- Consolidating metropolitan ecological systems and promoting new ecosystem services both outside and within the park [63], by accounting for metrics such as the amount of permeable soil and the presence of water surfaces capable of sustaining small-scale ecosystems, among other recognized parameters [64]. Parks located on the western side of the Llobregat could reinforce the connection between forests and river ecosystems, which could be emulated in the eastern side by reducing the fragmentation present in more urban parks through the greening of adjacent grey infrastructure.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMB | Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona (Barcelona Metropolitan Authority) |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| PDU | Pla Director Urbanístic (Masterplan) |

| FGC | Ferrocarrils de la Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan Government Railways) |

| NDVI | Normalised Difference Vegetation Index |

References

- Busquets, J.; Crosas, C.; Mariño, X.; Martínez, N.; Gómez, E. Barcelona Metròpolis de Ciutats: L’urbanisme Metropolità Avui; Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AMB. Pla Director Urbanístic Metropolità. Memòria Justificativa i d’Ordenació. Document d’Aprovació Inicial; AMB: Barcelona, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- AMB; BR. Sistema d’indicadors Ambientals Dels Parcs Metropolitans. Estudi Del PSAMB 2014–2020; AMB; BR: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AMB; BR. Indicadors Socioambientals de La Xarxa de Parcs Metropolitans. Dades de 2020; AMB; BR: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniak, J.; Hargreaves, G. Large Parks; Princeton Architectural Press; in association with the Harvard University Graduate School of Design: New York, NY, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781568986241. [Google Scholar]

- Dramstad, W.E.; Olson, J.D.; Forman, R.T.T. Landscape Ecology Principles in Landscape Architecture and Land-Use Planning; Harvard University Graduate School of Design; Island Press; American Society of Landscape Architects: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; ISBN 1559635142. 9781559635141. [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen, C.M.; Wouter, R. Metropolitan Landscape Architecture Urban Parks and Landscapes; Thoth: Bussum, SE, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 9789068685916. 9068685910. [Google Scholar]

- Batlle, E.; Forman, R.T.T.; Mayor, X.; Farrero, A.; Molina, P.; Rubert, M. Quaderns PDU Metropolità 03; AMB: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Batlle, E. El Jardí de La Metròpolis: Del Paisatge Romàntic a l’espai Lliure per a Una Ciutat Sostenible; Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- AMB; Crosas, C.; Jiménez, M. Directrius Urbanístiques “Àrees de Centralitat i Innovació”; Quadern 10. In Quaderns del PDU Metropolità; Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Barcelona Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity Plan 2020; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- AMB. Estudi Ambiental. Pla Director Urbanístic Metropolità; AMB: Barcelona, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Pla Natura Barcelona 2021–2030; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Busquets, J. Barcelona: The Urban Evolution of a Compact City; Nicolodi: Rovereto, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Solà-Morales, M. La Ciutadella and Montjuïc: The City Has Two Ears. In Ten Lessons on Barcelona; Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; pp. 409–463. [Google Scholar]

- Rubió i Tudurí, N.M. El Problema de Los Espacios Libres: Divulgación de Su Teoría y Notas Para Su Solución Práctica. In Proceedings of the XI Congreso Nacional de Arquitectos, Primero de Urbanismo; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Bohigas, O. Plans i Projectes per a Barcelona: 1981/1982, 2nd ed.; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, K. Graph Theory and Open-Space Network Design. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.B. Civilizing American Cities: A selection of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Writings on City Landscapes; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitzevsky, C. Frederick Law Olmsted and the Boston Park System; The Belknap Press: Cambridge, Spain, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wille, L. Forever Open, Clear, and Free: The Historic Struggle for Chicago’s Lakefront; Regnery: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Co, F. De los parques a la región: Ideología progresista y reforma de la ciudad americana. In La ciudad americana: De la guerra civil al New Deal; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, R.T.T. Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McHarg, I. Design with Nature; Doubleday-Natural History Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, D. Metrogreen: Connecting Open Space in North American Cities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, J.K.; Terando, A.J. Landscape Connectivity Planning for Adaptation to Future Climate and Land-Use Change. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2019, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lookingbill, T.R.; Minor, E.S.; Mullis, C.S.; Nunez-Mir, G. Connectivity in the Urban Landscape (2015–2020): Who? Where? What? When? Why? and How? Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2022, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Green Infrastructure (GI)—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital 2013; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Opportunities and Challenges for Business and Industry (Vol. 3); Island Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Green Biodiversity Strategy 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.; Hansen, R.; Rall, E.; Pauleit, S.; Lafortezza, R.; Bellis, Y.; Santos, A.; Tosics, I. Green Infrastructure Planning and Implementation—The Status of European Green Space Planning and Implementation Based on an Analysis of Selected European City-Regions; Green Surge: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Slätmo, E.; Nilsson, K.; Turunen, E. Implementing Green Infrastructure in Spatial Planning in Europe. Land 2019, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RVR. Green Infrastructure Strategy for the Ruhr Metropolis; Regionalverband Ruhr: North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mairie de Paris. Stratégie de Résilience de Paris; Mairie de Paris: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Lombardia. Rete Ecologica Regionale; Regione Lombardia: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Citta Metropolitana di Milano. Dorsale Verde Nord; Citta Metropolitana di Milano: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verde pubblico. Piano Strategico Dell’Infrastruttura Verde Torinese; Verde pubblico: Torino, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona; Parcs i Jardins; BR. Carta Del Verd i de La Biodiversitat; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.N.; van der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Nowak, D.J.; Kronenberg, J.; de Groot, R. Benefits of Restoring Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, S. El Libro Verde de Sostenibilidad Urbana y Local En La Era de La Información; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, Agencia de Ecología Urbana de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, R.T.T. Barcelona Regional. In Mosaico Territorial Para La Región Metropolitana de Barcelona; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lecroart, P.; IPR. The Parc Des Hauteurs Project, Paris. In URBAN Des; Institut Paris Region: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, J.; Baier, A.; Bürgow, G.; Simone, M.D.; Flötotto, J. GartenLeistungen. Der Wert Urbaner Gärten Und Parks: Was Stadtgrün Für Die Gesellschaft Leistet; Institut für ökologische Wirtschaftsforschung GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak, A. The Contribution of Local Parks to Neighbourhood Social Ties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberich, J.; Pérez-Albert, Y.; Morales, J.I.M.; Picón, E.B. Environmental Justice and Urban Parks. A Case Study Applied to Tarragona (Spain). Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostang, O.; Gren, A.; Feinberg, A.; Berghauser Pont, M. Promoting Resilient and Healthy Cities for Everyone in an Urban Planning Context by Assessing Green Area Accessibility. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braubach, M.; Egorov, A.; Mudu, P.; Wolf, T.; Ward Thompson, C.; Martuzzi, M. Effects of Urban Green Space on Environmental Health, Equity and Resilience. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 187–205. ISBN 978-3-319-56091-5. [Google Scholar]

- IDESCAT. Cens de Població i Habitatges; IDESCAT: Barcelona, Spain, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ermida, S.L.; Soares, P.; Mantas, V.; Göttsche, F.-M.; Trigo, I.F. Google Earth Engine Open-Source Code for Land Surface Temperature Estimation from the Landsat Series. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafray, E. Unique Projects of a Universal ‘Public Park Making’ Trend Viewed on the Example of Four Global Cities. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemann, H. The Conditions of Research by Design in Practice. In Proceedings of the Proceedings A/Research by Design; Ouwerkerk, V.M., Rosemann, H., Eds.; DUP Science: Delft, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Research by Design: Proposition for a Methodological Approach. Urban Sci. 2017, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, E.R.; DeMeulder, B.; Gerrits, Y. Design Studio as a Process of Inquiry: The Case of Studio Sao Paulo. Rev. Lusófona Arquit. e Educ. 2014, 11, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- van de Weijer, M.; Van Cleempoel, K.; Heynen, H. Positioning Research and Design in Academia and Practice: A Contribution to a Continuing Debate. Des. Issues 2014, 30, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMB; BR; CREAF. Diagnosi de l’estat de Conservació de La Biodiversitat Metropolitana; Direcció de Serveis Ambientals de l’AMB: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. GEOSTAT Census Grid 2021; Eurostat: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo González, J.; Crosas Armengol, C.; Royo Zabala, P. Del Andén a La Acera: Continuidades e Intermitencias Alrededor de Las Estaciones Ferroviarias de La Vall Baixa En La Barcelona Metropolitana. ACE Archit. City Environ. 2024, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, X.; AMB. Espacio Público En La Barcelona Metropolitana: Intervenciones y Diálogos, 2018–2022; Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; ISBN 9788487881503. [Google Scholar]

- Cranz, G.; Boland, M. Defining the Sustainable Park: A Fifth Model for Urban Parks. Landsc. J. 2004, 23, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priess, J.; Pinto, L.V.; Misiune, I.; Palliwoda, J. Ecosystem Service Use and the Motivations for Use in Central Parks in Three European Cities. Land 2021, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Brussels. Manuel Espaces Publics En Région de Bruxelles Capitale; Urban Brussels: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- RiConnect. RiConnect Case Studies; RiConnect: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- AMB; BR; CREAF. Serveis Ecosistèmics de La Infraestructura Verda de l’Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona: Primera Diagnosi; Direcció de Serveis Ambientals de l’AMB: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Soil Resource Efficiency in Urbanised Areas; EEA: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Park Name | Municipality | Area (ha.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pi Gros | Sant Vicenç dels Horts | 27.5 |

| 2 | Can Lluc | Santa Coloma de Cervelló | 8.9 |

| 3 | P. Cripta Güell | Santa Coloma de Cervelló | 5.7 |

| 4 | La Muntanyeta | Sant Boi de Llobregat | 29.7 |

| 5 | Torreblanca | Sant Just Desvern | 11.7 |

| 6 | Fontsanta | Sant Joan Despí | 29.0 |

| 7 | Can Mercader | Cornellà de Llobregat | 25.1 |

| 8 | De Les Planes | L’Hospitalet de Llobregat | 8.3 |

| Number | Park Name | Nearest Train Station | To Pl. Espanya |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pi Gros | 6 min (W) | 35 min (W + T) |

| 2 | Can Lluc | 5 min (W) | 30 min (W + T) |

| 3 | P. Cripta Güell | 6 min (W) | 29 min (W + T) |

| 4 | La Muntanyeta | 14 min (W) | 26 min (W + B) |

| 5 | Torreblanca | 7 min (W) | 42 min (W + B + T) |

| 6 | Fontsanta | 3 min (W) | 37 min (W + T + T) |

| 7 | Can Mercader | 8 min (W) | 22 min (W + T) |

| 8 | De Les Planes | 2 min (W) | 14 min (W + T) |

| N. | Proportion of the Park’s Green Space Within a 3 × 3 km Buffer | Intensity of Green (NDVI), 0–1. Authors, [4] | Biodiversity Index (Shannon Index), 0–3. Authors, [4] | Distance Between Park and Large Green Connector (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7% | 0.90 | 2.48 | 0 |

| 2 | 1% | 0.85 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 3 | 1% | 0.51 | - | 0 |

| 4 | 9% | 0.78 | 2.2 | 50 |

| 5 | 4% | 0.65 | 2.9 | 600 |

| 6 | 17% | 0.72 | 3 | 1100 |

| 7 | 16% | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1200 |

| 8 | 4% | 0.62 | 2.5 | 1400 |

| Av. | 7% | 0.73 | 2.3 | 540 |

| N. | % of Built-Up Areas within a 2 × 2 km Buffer | Potential Inhabitants in a 15 m Walking Buffer. Authors, [4] | Thermoregulation, Average Temperature 15 min Away from a Park/Average Temperature of a Park. Authors, [4] | Individual Average Gross Income within 500 m. Authors, [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18% | 19,000 | 0.8 | EUR 14,000 |

| 2 | 6% | 4000 | 0.9 | EUR 18,000 |

| 3 | 7% | 800 | 0.9 | EUR 16,500 |

| 4 | 28% | 20,000 | 1.48 | EUR 11,500 |

| 5 | 24% | 41,000 | 0.9 | EUR 15,000 |

| 6 | 30% | 58,000 | 3.48 | EUR 22,000 |

| 7 | 34% | 61,000 | 2.48 | EUR 13,500 |

| 8 | 40% | 135,000 | 0.75 | EUR 12,500 |

| Av. | 23% | 63,725 | 1.46 | EUR 15,375 |

| N. | Woods | Meadow | Scrubland | Water | Paths and Urbanized Areas | Playground | Built-Up | Parking Lots | Total (ha.) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.6 | 46% | 0.7 | 3% | 8.8 | 32% | 0 | 0% | 3.0 | 11% | 0.7 | 0.3% | 2.2 | 8% | 0.6 | 0.2% | 27.5 |

| 2 | 2.3 | 26% | 2.3 | 26% | 1.8 | 20% | 0 | 0% | 1.8 | 21% | 0.3 | 3% | 0 | 0% | 0.4 | 5% | 8.9 |

| 3 | 2.6 | 45% | 0.3 | 6% | 0.8 | 14% | 0.05 | 0% | 0.9 | 15% | 0.6 | 10% | 0.2 | 3% | 0.4 | 7% | 5.7 |

| 4 | 5.9 | 20% | 6.4 | 22% | 4.6 | 15% | 0.5 | 2% | 7.0 | 24% | 3.3 | 11% | 1.1 | 4% | 0.9 | 3% | 29.7 |

| 5 | 4.3 | 37% | 2.0 | 17% | 0.7 | 6% | 0.4 | 4% | 3.2 | 27% | 0.2 | 1% | 0.3 | 2% | 0.6 | 5% | 11.7 |

| 6 | 2.2 | 7% | 5.9 | 20% | 6.1 | 21% | 0 | 0% | 10.2 | 35% | 1.6 | 5% | 1.3 | 4% | 1.9 | 7% | 29.0 |

| 7 | 7.1 | 28% | 5.8 | 23% | 1.9 | 7% | 0.3 | 1% | 7.8 | 31% | 1.1 | 5% | 0.6 | 2% | 0.4 | 2% | 25.1 |

| 8 | 2.0 | 24% | 1.5 | 18% | 0.1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 3.2 | 39% | 1.1 | 13% | 0.1 | 1% | 0.3 | 3% | 8.3 |

| Av. | 4.1 | 29% | 3.7 | 17% | 4.3 | 14% | 1.4 | 1% | 4 | 25% | 2.2 | 6% | 1.4 | 3% | 2.9 | 4% | 11.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Florit-Femenias, J.; Crosas, C.; Saura-Vallverdú, A. “Metropolitan Parks” in Southern Barcelona: Key Nodes at the Intersection of Green Infrastructure and the Polycentric Urban Structure. Land 2025, 14, 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071432

Florit-Femenias J, Crosas C, Saura-Vallverdú A. “Metropolitan Parks” in Southern Barcelona: Key Nodes at the Intersection of Green Infrastructure and the Polycentric Urban Structure. Land. 2025; 14(7):1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071432

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlorit-Femenias, Joan, Carles Crosas, and Aleix Saura-Vallverdú. 2025. "“Metropolitan Parks” in Southern Barcelona: Key Nodes at the Intersection of Green Infrastructure and the Polycentric Urban Structure" Land 14, no. 7: 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071432

APA StyleFlorit-Femenias, J., Crosas, C., & Saura-Vallverdú, A. (2025). “Metropolitan Parks” in Southern Barcelona: Key Nodes at the Intersection of Green Infrastructure and the Polycentric Urban Structure. Land, 14(7), 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071432