Evaluating Landslide Detection and Prediction Potential Using Satellite-Derived Vegetation Indices in South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

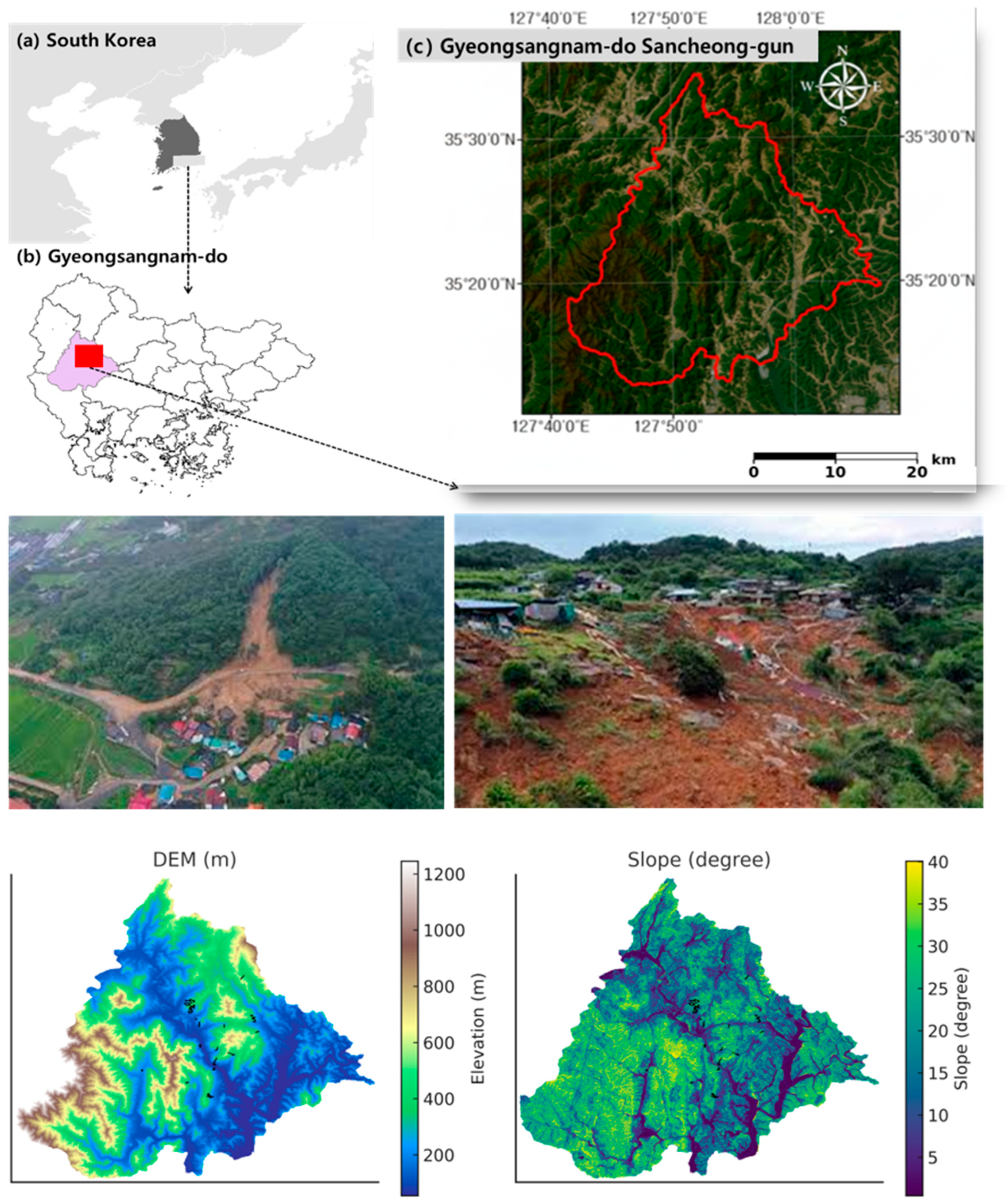

2.1. Survey Area

2.2. Study Overview

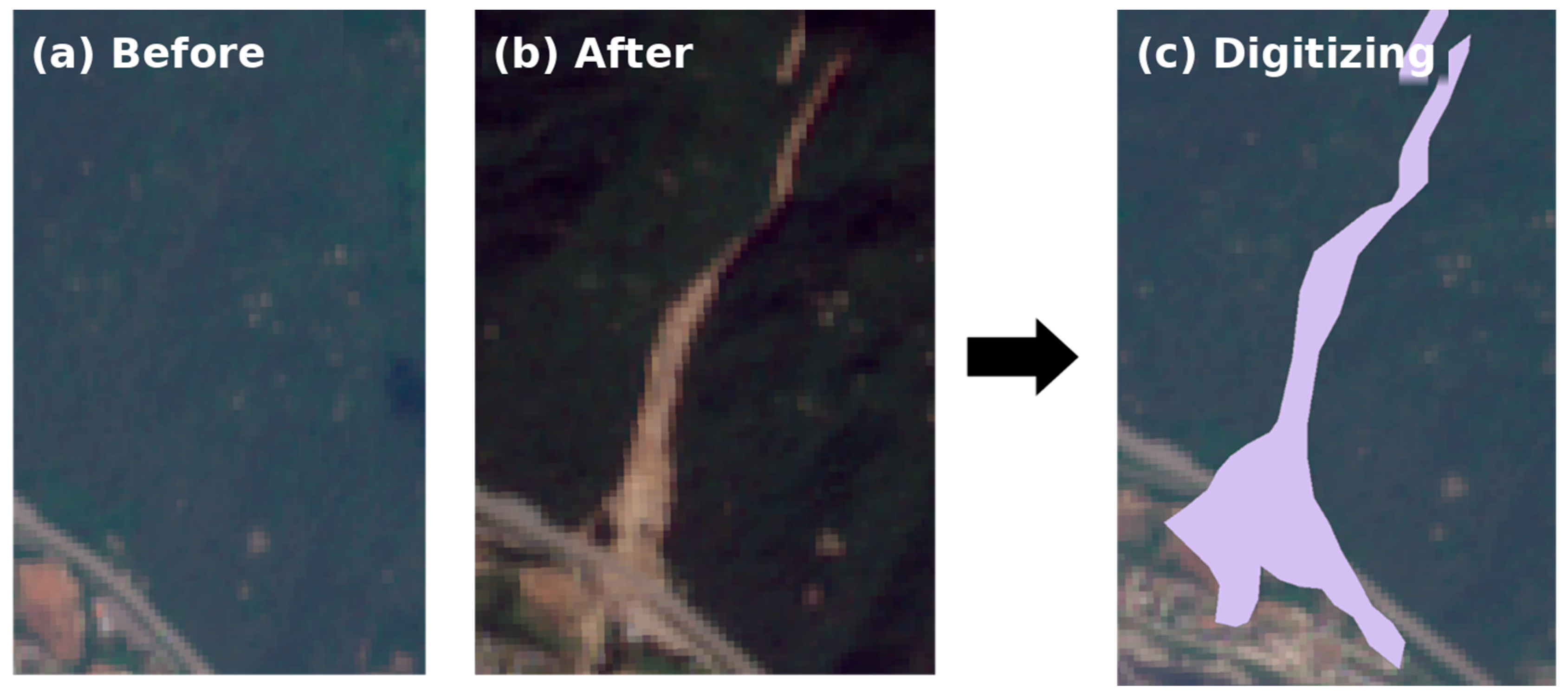

2.3. Data Preparation

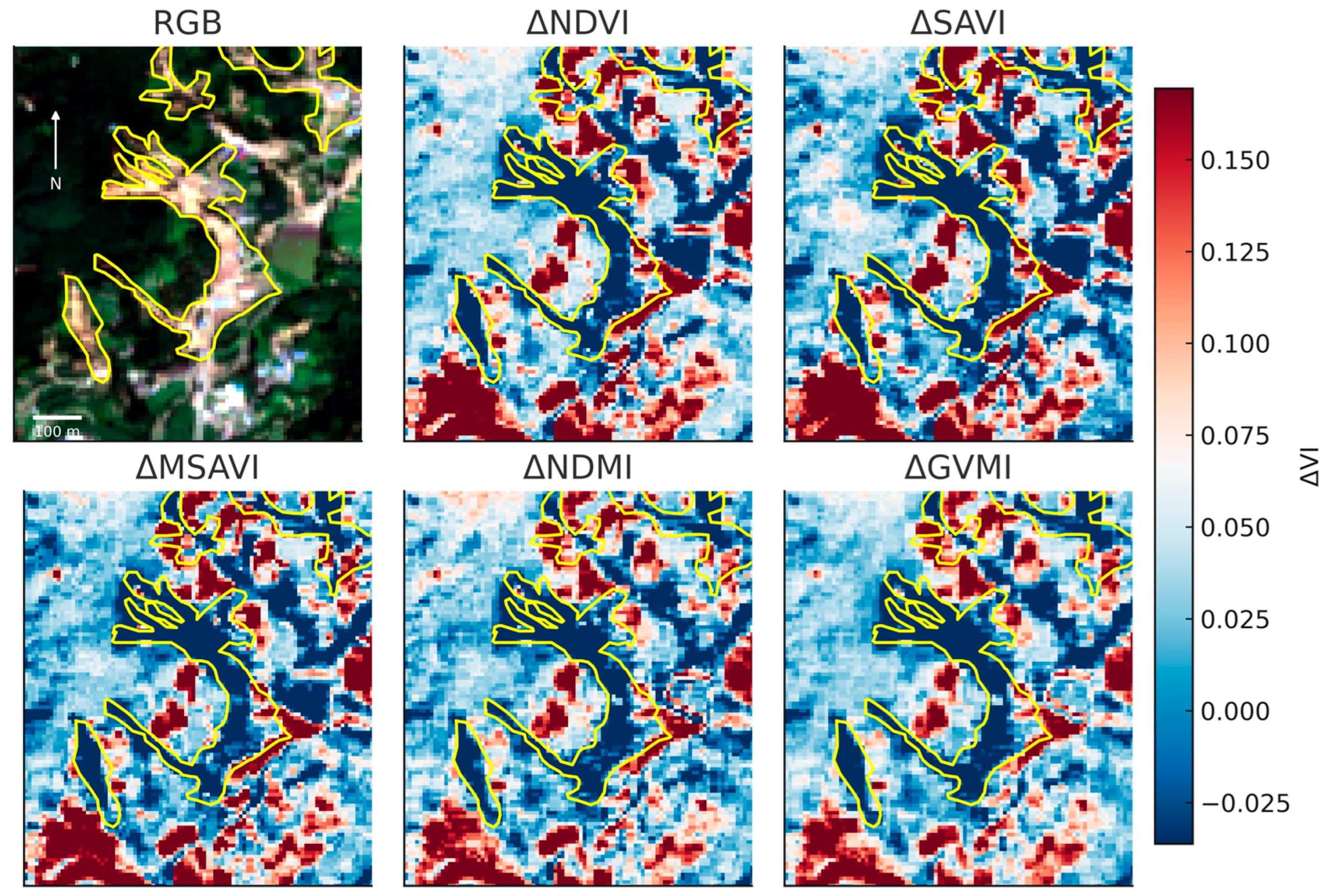

2.4. Vegetation Indices and ΔVI Computation

2.5. PD–ND Comparison Design

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. ΔVI Extraction and Two-Group Difference Testing

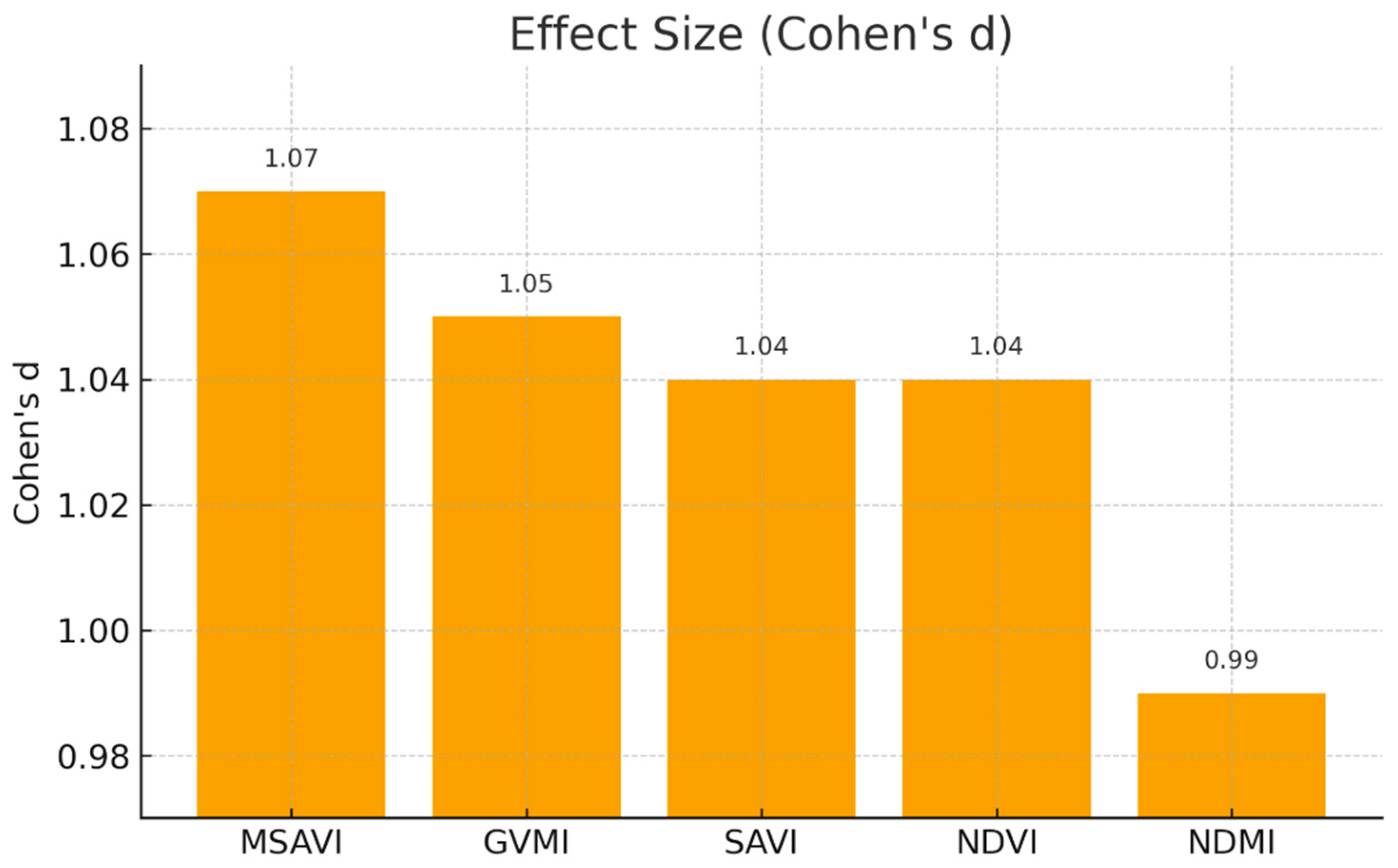

2.6.2. Effect Size: Cohen’s d

2.6.3. Composite Evaluation Metrics and Visualization

3. Results

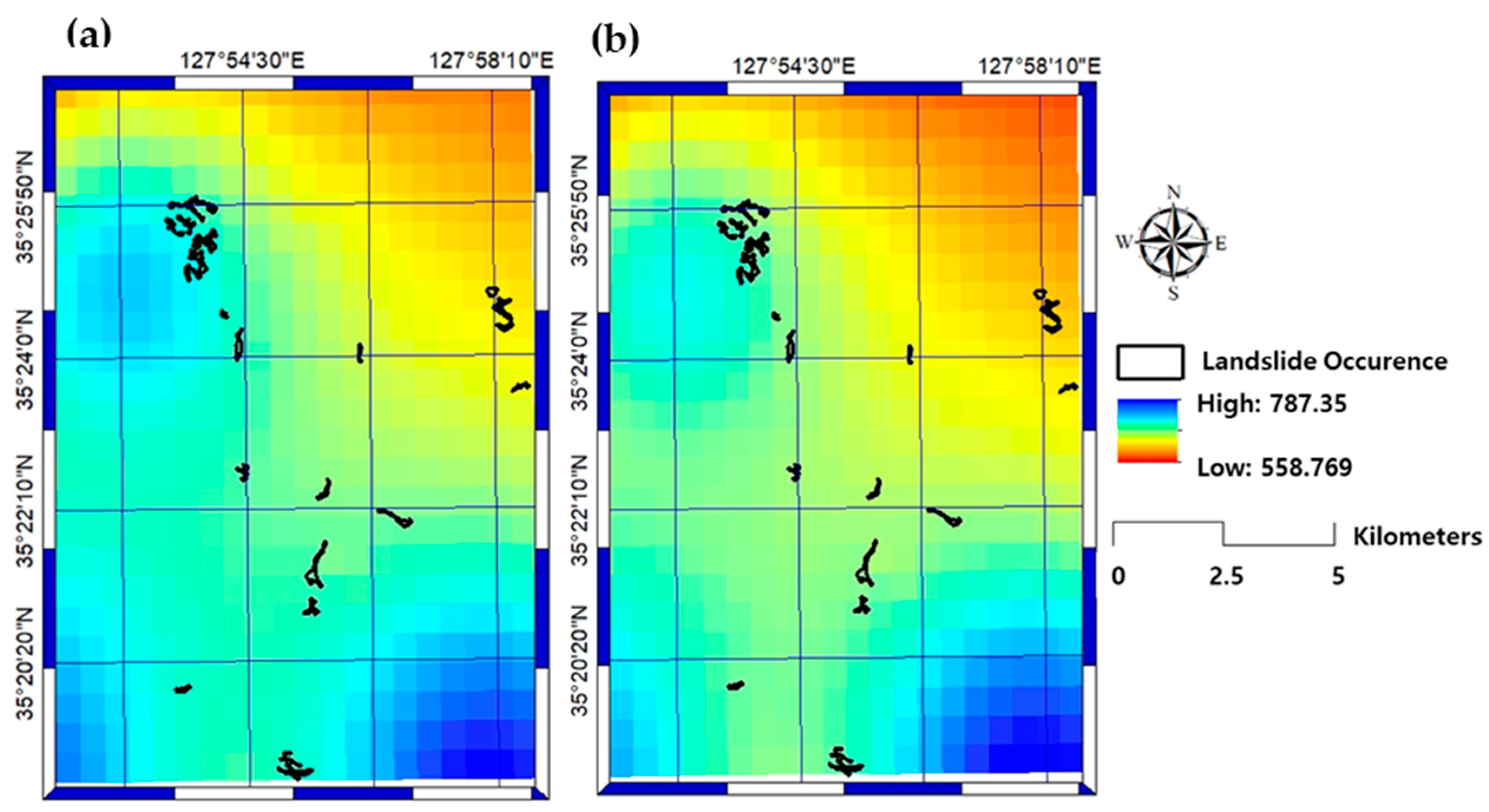

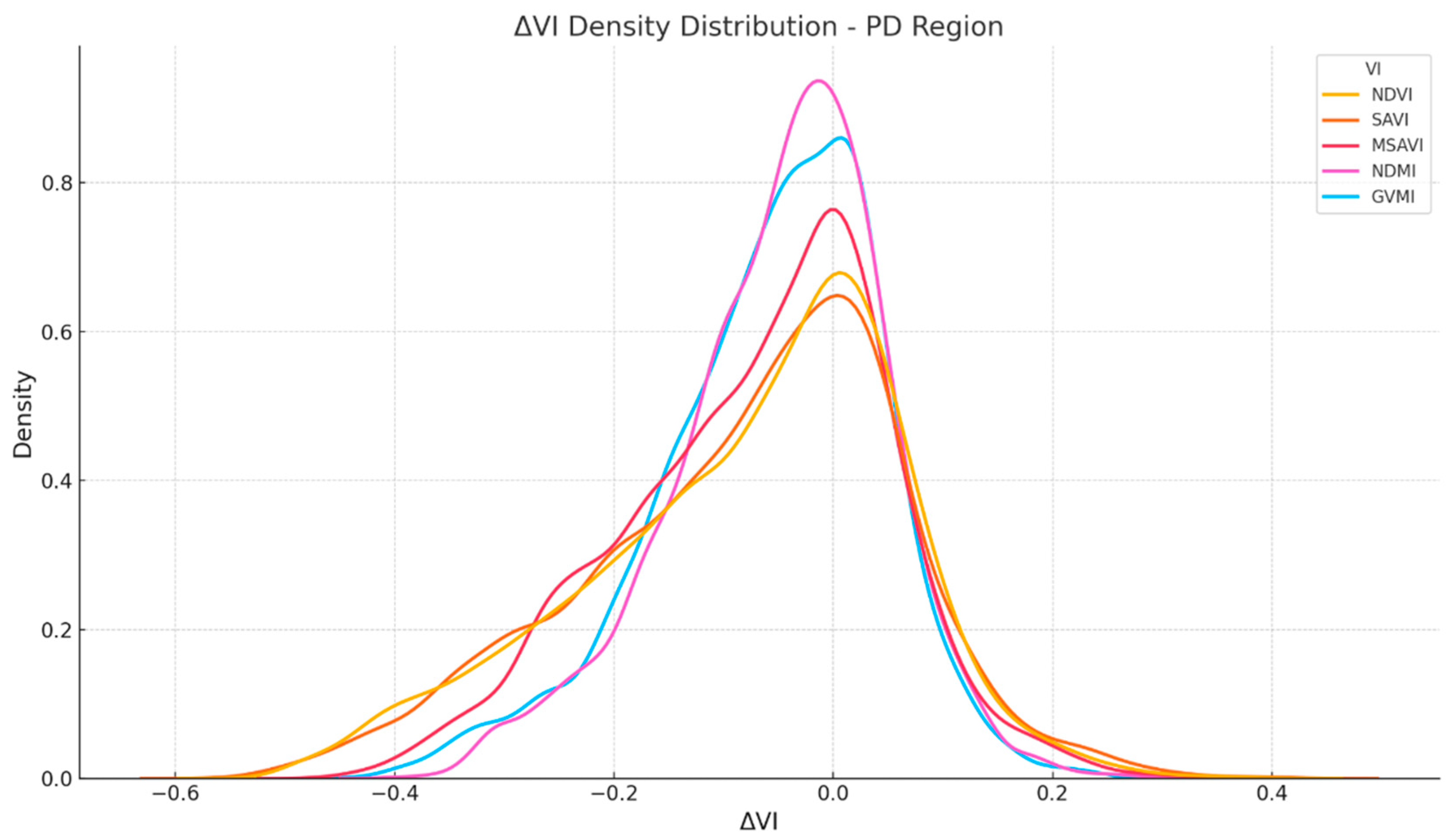

3.1. Regional Trends in Vegetation-Index Change

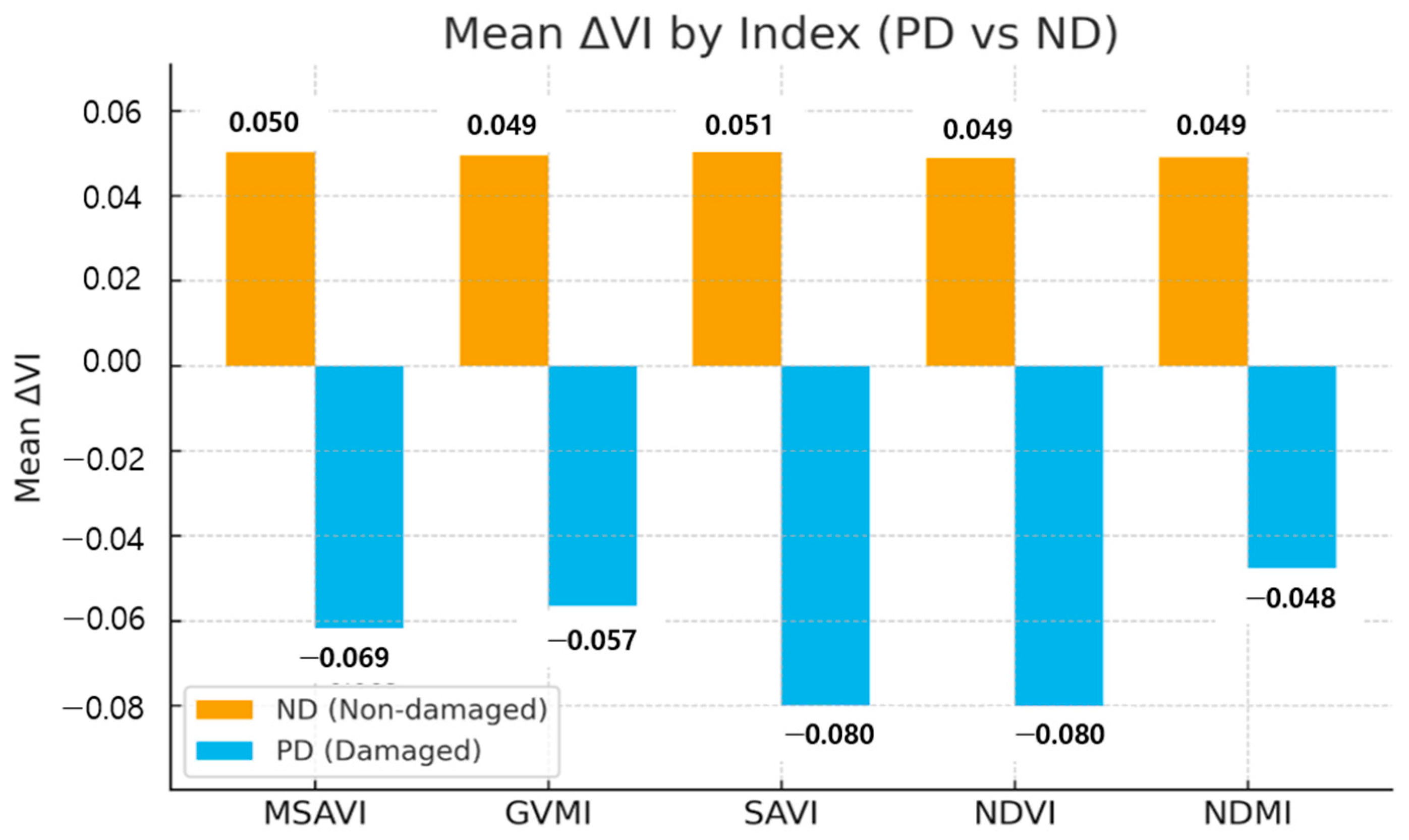

3.2. ΔVI-Based Damage Discrimination

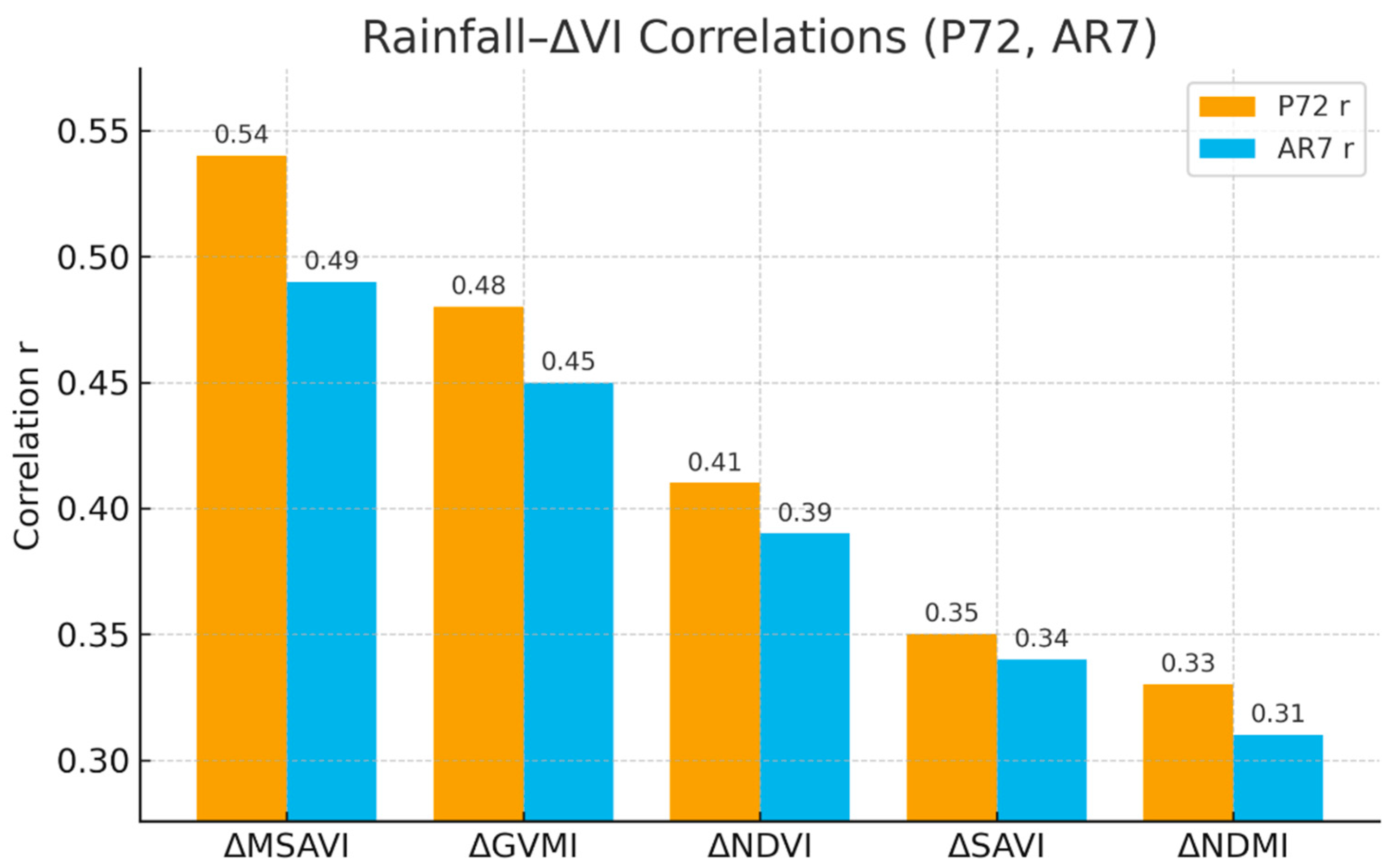

3.3. Rainfall–ΔVI Correlation Analysis

3.4. Robustness Checks

4. Discussion

4.1. Performance of ΔVI Metrics for Landslide Detection

4.2. Implications for Monitoring and Early Warning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASOS | Automated Synoptic Observing System |

| AWS | Automatic Weather Station |

| EWS | Early-warning system |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GVMI | Global vegetation moisture index |

| KFS | Korea Forest Service |

| KMA | Korea Meteorological Administration |

| ND | Non-damaged |

| MSAVI | Modified soil-adjusted vegetation index |

| MSI | MultiSpectral Instrument |

| NIR | Near infrared |

| NDMI | Normalized difference moisture index |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index |

| PD | Post-disaster |

| SAVI | Soil-adjusted vegetation index |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| VI | Vegetation index |

References

- Houghton, J.T.; Ding, Y.D.; Griggs, D.J.; Noguer, M.; van der Linden, P.J.; Dai, X.; Maskell, K. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Johnson, C.A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, E.W. Landslides in Southeast Asia: A State-of-the-Art. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Landslides, Toronto, ON, Canada, 16–21 September 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Service (KFS). Statistical Yearbook of Forestry; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. Rainfall thresholds for landslide initiation in Korea. Eng. Geol. 2018, 239, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Pradhan, B. Landslide hazard mapping at Selangor, Malaysia using frequency ratio and logistic regression. Landslides 2007, 4, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Tuan, T.A.; Klempe, H.; Pradhan, B.; Revhaug, I. Spatial prediction models for shallow landslide hazards: A comparative assessment. Geomorphology 2020, 359, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi, F.; Vangi, E.; Francini, S.; D’Amico, G.; Chirici, G.; Marchetti, M.; Lombardi, F.; Travaglini, D.; Ravera, S.; De Santis, E.; et al. Sentinel-2 time series analysis for monitoring multi-taxon biodiversity in mountain beech forests. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1020477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.-C. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A modified soil adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Sun, X.; Liu, S. Selection of control areas for vegetation change analysis after landslides. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Dai, E. Vegetation cover dynamics and its constraint effect on ecosystem services on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau under ecological restoration projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Vierling, L.; Deering, D. A simple and effective radiometric correction method to improve landscape change detection across sensors and across time. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 98, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Didehban, K.; Rasouli, H.; Kamran, K.V.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. An Application of Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and GNSS Data for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafi, A.A.; Tsangaratos, P.; Ilia, I.; Chen, W. Rapid landslide detection following an extreme rainfall event using remote sensing indices, synthetic aperture radar imagery, and probabilistic methods. Land 2024, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D.; Zhang, J.; Sharma, A. Geographic object-based image analysis for landslide identification using machine learning on Google Earth Engine. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Sawada, K.; Moriguchi, S. Landslide susceptibility analysis with logistic regression model based on FCM sampling strategy. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 57, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, P. Mapping Snow and Vegetation Coverage Using Multitemporal Open Satellite Imagery: The Case Study of the Maritime Alps. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- van t’ Loo, K. Monitoring with Vegetation Indices: How Vegetation Recovers on Landslides in Dominican Tropical Forest. Master’s Thesis, Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, Zwolle, The Netherlands, 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354059041 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhou, L.; Lin, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y. Assessing landslide-induced vegetation loss using combined Landsat and Sentinel-2 imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102853. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Third ERTS Symposium; NASA SP-351; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; Volume I, pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Kwon, J. Landslide susceptibility mapping based on field survey and optical imagery. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Yun, H.; Lim, K. Mapping post-disaster landslide extent using Sentinel-2 and object-based image analysis. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2955. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Improving landslide mapping accuracy using buffer zone filtering of boundary pixels. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 90, 102117. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.; Lee, D.; Kim, M. A comparative analysis of landslide and non-landslide areas using DEM and NDVI. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2019, 35, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus WorldCover Team. ESA WorldCover 10 m v100 [Dataset]. 2021. Available online: https://esa-worldcover.org (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhu, C.; Fang, C.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Yan, J.; He, M.; Cheng, Z. Remote Sensing Techniques for Landslide Prediction, Monitoring, and Early Warning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsias, N.; Kalabokidis, K.D.; Allgöwer, B. Fire occurrence patterns at landscape level: Beyond positional accuracy of ignition points with kernel density estimation methods. Nat. Res. Mod. 2004, 17, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, C.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, Y. Object-based change detection for vegetation disturbance and recovery using Landsat time series. GIScience Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1706–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K.; Nakaoka, Y.; Okumura, H. Method for landslide area detection with RVI data which indicates base soil areas changed from vegetated areas. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, S.; Ji, T. The impact of super typhoon on varying vegetation types in eastern coastal China: Implications for coastal ecosystem and disaster risk management. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2523482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Pan, Y.; Ren, S.; Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, G. Accurate Vegetation Destruction Detection Using Remote Sensing Imagery Based on the Three-Band Difference Vegetation Index (TBDVI) and Dual-Temporal Detection Method. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 127, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; Maltese, A.; Conoscenti, C. Automated Dating of Recent Landslides Using Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; de Jong, S.M.; Deijns, A.A.J.; Geertsema, M.; de Haas, T. The SWADE Model for Landslide Dating in Time Series of Optical Satellite Imagery. Landslides 2023, 20, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vegetation Index | Formula (Sentinel-2 Band Basis) | Key Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) | (B8 − B4)/(B8 + B4) | - Most basic greenness index - Sensitive to leaf area and photosynthetic activity - Susceptible to soil exposure (soil brightness effects) | Rouse et al., 1974 [21] |

| SAVI (Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index) | (B8 − B4)/(B8 + B4 + L) × (1 + L) L = 0.5 | - Adjusts for soil brightness effects - More stable than NDVI in sparsely vegetated areas - Suited to areas with increased exposed soil - L: Soil brightness correction factor | Huete, 1988 [8] |

| MSAVI (Modified SAVI) | 0.5 × [2 × B8 + 1 − √((2 × B8 + 1)2 − 8 × (B8 − B4))] | - Self-adjusting soil correction - More robust than NDVI and SAVI over exposed areas - Effective at suppressing noise | Qi et al., 1994 [10] |

| NDMI (Normalized Difference Moisture Index) | (B8 − B11)/(B8 + B11) | - Sensitive to vegetation canopy water content - Responds to canopy loss and moisture/saturation transitions - Foundational indicator on the moisture axis | Gao, 1996 [9] |

| GVMI (Global Vegetation Moisture Index) | (B8 − B12)/(B8 + B12) | - Similar to NDMI but uses a broader SWIR range - Sensitive to near-surface (topsoil) moisture state - Enhances structural contrast | Chen et al., 2005 [13] |

| VI | 1% (q01) | 5% (q05) | 25% (q25) | 50% (q50) | 75% (q75) | 95% (q95) | 99% (q99) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSAVI | −0.1588 | −0.0419 | 0.0133 | 0.0373 | 0.0693 | 0.1765 | 0.2880 |

| GVMI | −0.1159 | −0.0206 | 0.0230 | 0.0406 | 0.0621 | 0.1412 | 0.2248 |

| SAVI | −0.1901 | −0.0483 | 0.0161 | 0.0430 | 0.0773 | 0.2027 | 0.3317 |

| NDVI | −0.1939 | −0.0369 | 0.0256 | 0.0466 | 0.0759 | 0.1867 | 0.3188 |

| NDMI | −0.1125 | −0.0331 | 0.0135 | 0.0370 | 0.0628 | 0.1464 | 0.2357 |

| VI | Mean ΔVI (ND) | Mean ΔVI (PD) | t | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSAVI | +0.0502 | −0.0691 | 74.6 | <0.001 | 1.07 |

| GVMI | +0.0494 | −0.0566 | 73.4 | <0.001 | 1.05 |

| SAVI | +0.0511 | −0.0801 | 73.0 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| NDVI | +0.0489 | −0.0802 | 72.5 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| NDMI | +0.0490 | −0.0477 | 69.4 | <0.001 | 0.99 |

| ΔVI | P72 (Prior 72 h) | AR7 (Following 7 Days) |

|---|---|---|

| ΔMSAVI | 0.54 | 0.49 |

| ΔGVMI | 0.48 | 0.45 |

| ΔNDVI | 0.41 | 0.39 |

| ΔSAVI | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| ΔNDMI | 0.33 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H. Evaluating Landslide Detection and Prediction Potential Using Satellite-Derived Vegetation Indices in South Korea. Land 2025, 14, 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122410

Lee J, Lee S, Lee H. Evaluating Landslide Detection and Prediction Potential Using Satellite-Derived Vegetation Indices in South Korea. Land. 2025; 14(12):2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122410

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Junhee, Sunjoo Lee, and Hosang Lee. 2025. "Evaluating Landslide Detection and Prediction Potential Using Satellite-Derived Vegetation Indices in South Korea" Land 14, no. 12: 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122410

APA StyleLee, J., Lee, S., & Lee, H. (2025). Evaluating Landslide Detection and Prediction Potential Using Satellite-Derived Vegetation Indices in South Korea. Land, 14(12), 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122410