1. Introduction

Rural areas across Europe are facing increasing territorial inequalities and the constant abandonment of agricultural land, which is becoming a serious obstacle to sustainable development and spatial cohesion. In mountainous and island regions, these problems are even more pronounced due to a combination of natural constraints and economic pressures. According to an analysis by the European Parliament, almost a third of agricultural land in the EU-27 member states is at risk of abandonment [

1]. In the mountain communities of the Troodos, these negative trends are particularly pronounced: the degradation of agricultural terraces, the decline in production capacities and the long-term demographic recession have led to a dramatic reduction in the extent of traditionally cultivated areas during the last few decades [

2]. Estimates based on the comparative processing of historical cartographic sources and CORINE Land Cover (CLC) data indicate that during the last few decades there has been a very significant reduction in traditionally cultivated agricultural areas in Cyprus. Available analyses suggest that long-term losses of actively used land in certain rural areas reach very high values, especially in the Troodos mountain zone, where depopulation has accelerated the process of abandoning terraced areas. Such a finding does not represent a fixed one-parameter calculation, but an indicative balance of the long-term process of transformation of the agrarian landscape, based on decades of continuous changes in land use. Such processes change the cultural and landscape identity of communities, causing loss of local knowledge, soil erosion and weakening of social cohesion. At the same time, the visual appearance of the landscape and the ecological balance are disturbed, which increases the risk of erosion, depopulation and social fragmentation in rural areas.

The digital transformation of agriculture is emerging as a modern development model that goes beyond the limits of the production sector and becomes a means of territorial renewal and spatial integration. Digital agriculture involves the application of precision technologies, satellite and drone surveillance, sensor networks, IoT systems and digital management platforms [

3,

4]. It provides an opportunity for the creation of conditions conducive to the efficient, sustainable and integrated management of land, water resources and production cycles. According to the European Parliament report [

5] on digital agriculture, modern technologies can increase productivity and resource efficiency, reducing pressure on the environment while strengthening the resilience of rural communities. The Council of the European Union [

6], in its strategy for agriculture and rural development additionally, emphasizes that digital solutions are a key instrument for the modernization and spatial sustainability of agricultural areas. The Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, through the Agricultural Research Institute (ARI), is implementing a number of projects in the field of precision agriculture and information and communication technologies [

7,

8]. The aim is monitoring irrigation and using drones for crop surveillance [

9]. These activities confirm that the digital transition on the island has become a measurable and visible process. As pointed out by Finger [

10] and Ferrari [

11], digital innovations contribute to building more resilient production systems and reducing structural differences between developed and marginalized regions.

Ronzhin et al. [

12] emphasize that the biggest challenges in implementing digital solutions are related to the lack of infrastructure, educational capacities and institutional support, especially in peripheral and mountainous areas. It is in such environments, such as the mountain communities of Troodos, that digital agriculture can become a key mechanism for the revitalization of neglected areas and the renewal of local economic ties. Research by Gousios et al. [

13] shows that the combination of GIS analysis, satellite data and local knowledge enables the development of precise plans for the restoration of terraces and the rational management of water resources. This approach connects local communities with digital tools and creates the foundations for the concept of “smart territorial restructuring”. The model that combines digital agriculture, spatial planning and resource management. The process is fully aligned with the EU Territorial Agenda 2030, Common Agricultural Policy 2023–2027, and the Smart Villages initiative, which promote territorial justice, local innovation and digital connectivity as the basic pillars of sustainable development [

14]. In Cyprus, where spatial inequalities are pronounced between coastal and inland municipalities, digital agriculture is emerging as a key lever for balanced spatial development, preserving rural resilience and reducing regional disparities [

15]. The aim of this paper is to analytically determine how the degree of digital adoption in agriculture affects land revitalization, spatial integration and resilience of rural communities in different regions of Cyprus. Based on a combination of spatial, institutional and technological analysis, the “Smart Territorial Restructuring” framework was developed, which connects digital technologies with territorial development. In this way, the work contributes to a new perspective of understanding the digital transition not only as a technological, but also as a spatial-structural transformation that enables the reduction in regional differences and the strengthening of local cohesion.

Starting from the mentioned challenges and strategic priorities, this research directs attention to the following research questions:

- (1)

How does the level of adoption of digital solutions in agriculture affect the use and revitalization of land in different rural areas of Cyprus?

- (2)

Do more digitally advanced municipalities form spatial clusters of greater territorial connectivity and resilience, and how do they differ from municipalities with a low level of digitization?

- (3)

Through which institutional and technological mechanisms does digital agriculture contribute to smart territorial restructuring and the reduction in regional disparities?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

Digital agriculture and spatial land management are increasingly seen in European and international research as interdependent processes that, when strategically coordinated, can significantly contribute to the renewal of rural areas and the reduction in territorial inequalities. The digitization of agriculture implies the unified application of ICT technologies, sensor networks, satellite monitoring and data-based management throughout the entire agro-chain, from the collection of information on the plot and decision-making at the farm level, to the planning and management of resources at the municipal or regional level [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The European Commission directly connects this approach with the modernization and sustainability of agriculture, emphasizing that digitization should simultaneously increase productivity, reduce pressure on natural resources and improve the quality of life in rural [

20]. The main challenges do not stem from a lack of technology, but from the need for stronger educational programs, practical demonstrations and more effective market connections, so that digital solutions can really contribute to sustainable results in practice. At the same time, recent JRC reports show that the development of digital tools cannot be seen only as a technological replacement, but as part of a wider transformation of institutional and organizational structures, more precisely, as a transition to data-based management in which spatial information, regulations and local development goals are tied into one system [

21]. Such a systemic view is particularly visible in the documents accompanying the new CAP 2023–2027, where it is insisted that digital solutions should be a function of territorial cohesion and a long-term vision for rural areas until 2040 [

22,

23]. According to research on the digitization of rural areas, the process of change is never smooth. Island, mountain and peripheral regions are slower to adopt digital technologies. The causes of such differences arise from complex ownership and land relations, insufficiently developed infrastructure and lack of appropriate institutional support [

24,

25,

26,

27]. This pattern is particularly pronounced in Mediterranean and island economies, where agriculture is fragmented, heavily dependent on water resources and exposed to climate change. Research on smart and climate-smart agriculture in Cyprus [

28] indicates that Cypriot farmers are slower to accept modern technologies, due to the need for stronger educational initiatives, practical training.

Theories of territorial cohesion and spatial justice in the EU show that rural development is no longer seen only as an increase in agricultural production, but as a strengthening of the connection between space, communities and infrastructure. Works on spatial justice and territorial cohesion in the EU emphasize that it is necessary to link agriculture, cohesion and digitization policies in order to reduce intra-state differences, especially in small and island states where development resources are concentrated in coastal and metropolitan areas [

29,

30,

31]. In this sense, digital agriculture is increasingly described in the literature as an “enabler” of territorial cohesion, because it enables spatial data, local needs and European development instruments to be combined into one operational framework [

32,

33]. Digital agriculture and territorial cohesion can be combined into a concept that we call “smart territorial restructuring” in this paper. In this framework, digital technologies are not only a means to increase yield or save water, but a catalyst for spatial reorganization: local communities receive more accurate data, GIS analyzes identify abandoned or fragmented areas, and digital platforms enable decisions to be made at the level where the problems originated. This is exactly what the ITU-FAO reports [

34] for European and pre-accession countries emphasize: digitalization has its full effect only when it is linked to decentralized land management and to local development networks, such as Smart Villages and local cooperatives. Examples in the literature confirm this synergy. Studies from Mediterranean rural areas show that regions that have adopted precision irrigation, and data sharing platforms have less decline in agricultural areas and slower depopulation [

35,

36]. Projects of smart irrigation and digital monitoring of water resources have been developed precisely to respond to water scarcity, which also gives them a spatial-ecological dimension. Studies by the SHERPA network show that rural communities that lack digital infrastructure or institutional capacity remain “digitally marginalized” [

23,

25,

37]. At the policy level, clear connections can be seen between the new CAP 2023–2027, the Smart Villages initiative, the long-term vision for rural areas until 2040 and the broader objective of territorial cohesion from the Territorial Agenda 2030. The European Commission clearly states in the documents on smart villages that digital transitions should serve “connecting people, places and services” in rural areas, not just agricultural productivity. This means that digital agriculture takes on a double role: technological (precise management of resources) and management (smart integration of space). For this very reason, this paper adopts the “smart territorial restructuring” model as a theoretical support for the analysis of Cypriot municipalities, and methodologically relies on the interdisciplinary combination of spatial geography, agrarian economy, digital technologies and European cohesion policies [

38,

39].

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach of this research is based on a combination of spatial-analytical data on land use, official statistics on agricultural activity and secondary sources on the degree of digitization of agriculture in EU member states, with a focus on applicability to the Cypriot context. The starting point was the creation of a consistent spatial database on the state and changes in land use in Cyprus, for which the CORINE Land Cover (CLC) (

https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover, accessed on 15 October 2025) corpus was used, which is available for Cyprus through the national opendata portal and the Copernicus Land Monitoring Service, and which enables the classification of surfaces into 44 thematic classes and the monitoring of changes in six-year update cycles [

40,

41]. This source was chosen because it is standardized at the EU level, has already been used in national landscape mapping projects and LULC maps for Cyprus and because it allows agricultural areas, vineyards, olive groves and abandoned or degraded lands to be extracted into separate layers for further analysis [

42,

43,

44].

It is important to emphasize that the CLC 2024 data used in this research represent a preliminary data set within the current update cycle of the Copernicus program. The final and fully verified CLC 2024 layers were announced by the European Environment Agency for 2026. The interpretation of changes in land use includes a certain degree of indicativeness, conditioned by the phase in which the data is currently in the process of updating.

Based on the CLC layers, agricultural classes relevant to rural municipalities in the interior of the island were separated and an indicative layer of “potentially abandoned agricultural areas” was formed through a comparison of the situation in two time sections, based on the method developed by the Joint Research Center (JRC) for modeling the abandonment of agricultural land in the EU [

45,

46]. This approach relies on the already proven practice of modeling the risk of abandonment as a result of multiple factors, demographic, agro-economic and accessibility factors, although in this work, due to data availability, the emphasis is on spatial and production indicators, and not on a full utilitarian-model projection as used by the LUISA platform [

47,

48]. Spatial processing was performed in the QGIS 3.x and ArcGIS Pro environment, which is a standard in EU works combining Copernicus layers and local administrative boundaries [

49,

50].

Table 1 shows the main sources used in the research. Copernicus satellite data enabled spatial analysis and monitoring of changes in land use, while institutional documents and development programs provided good background for the digital transformation of rural areas. The second pillar of the methodology refers to the measurement and spatial attribution of the level of digitization of agriculture. The latest report of the Joint Research Center of the European Commission “The State of Digitalisation in EU Agriculture” was used, which provides a structure of indicators on the use of general IT software, data collection and incentives for the adoption of digital solutions in agriculture [

21]. The structure of this report is compatible with previous works on the digital readiness of EU farms [

51,

52] on the basis of which a complex index of the digital readiness of agriculture was developed. This index enables systematic monitoring of the level of digital transformation of the agricultural sector and comparability of results between different regions and EU member states. For its preparation, national data were used [

53], as well as additional information from the CAP Strategic Plan Cyprus 2023–2027 and Smart Rural Factsheet 27 for Cyprus. Each municipality was assigned a value according to three groups of indicators: (i) investments in digital and precision agriculture and projects financed from CAP funds; (ii) availability and use of digital advisory and e-agri services developed by ARI and/or the ministry; (iii) the presence of smart water resource management projects and climate smart solutions, which is of particular importance in the conditions of limited water resources in Cyprus [

26,

28,

35]. The index relies on real, published and administratively verified data sources.

Table 2 shows that Cyprus has a high digital infrastructure (93% internet coverage) but also a relatively low degree of practical adoption of technologies in agriculture (14%). This discrepancy indicates that the infrastructural conditions exist, but that institutional support, education and local capacities still limit the full digital transformation of the sector. The third step in the methodology was the integration of spatial and development data in a GIS 3.28 environment. CLC 2018/2024 layers, land data from the Town Planning and Housing Department and municipal boundaries were loaded into QGIS/ArcGIS and overlaid with the calculated digital readiness index. At the municipal level (LAU), indicators were derived: the share of agricultural land, “arable but not used” land, the share of permanent plantings and the density of digital interventions. To ensure that spatial patterns are not random, standard measures of spatial autocorrelation, global Moran’s I and local LISA, which are often used in EU studies on land abandonment and rural disparities [

46] were applied. These indicators make it possible to quantify whether more digitally active areas form spatially connected clusters and whether these clusters coincide with areas where greater resilience of rural communities is recorded. A similar approach was used in works on digital clusters in Spain and Portugal [

31,

36], so it is methodologically completely acceptable for the Cypriot case as well.

In addition to the existing indicators that measure the volume of investment and institutional coverage of digital projects, descriptive-dynamic indicators of the adoption of digital technologies in agriculture were also introduced in order to capture real effects on the ground. These indicators include: (i) the degree of use of digital advisory services (frequency of access to platforms and consultations with expert services), (ii) duration of continuous application of intelligent technologies on farms (e.g., smart irrigation systems and IoT sensors), and (iii) frequency of digital interactions in the value chain (use of digital platforms for product placement and production records). In the absence of unique quantitative data for the entire territory of Cyprus, part of this information was collected through the analysis of project reports of ARI and the Smart Village initiative, as well as through a descriptive insight into the duration and intensity of pilot projects in viticulture, citrus and olive growing. In this way, it is ensured that the methodology includes not only the availability of technologies, but also the actual practice of their application, which is a key element of the assessment of the digital transformation of agriculture.

The fourth element of the methodology refers to the qualitative interpretation and triangulation of the findings. Since the data on digital interventions in Cyprus are fragmented between ministries, EU projects and local initiatives (e.g., precision agriculture pilot projects in viticulture, citrus and olive growing), the quantitative findings are supplemented by a desk-analysis of strategic and programmatic documents: Rural Development Program of Cyprus, CAP Strategic Plan Cyprus 2023–2027, reports on the implementation of the Smart Villages Initiative and national reports on the digital transition of agriculture. This triangulation procedure is recommended by the ITU-FAO (2024) [

34] and the SHERPA network [

61], who emphasize that in small member states data are often unevenly available and that their linking with policy documents is necessary for the analysis to be usable. Through this step, it is ensured that the micro-level (municipality, project, farmer) is connected with the macro-level (EU policy, national plan, CAP funding), which is important because one of the goals of the work is to show that digital agriculture can be an instrument of territorial restructuring if there is an institutional channel through which local innovations “climb” to the national level.

All results are presented at the level of municipalities (LAU) because that level best reflects the real development differences within Cyprus and enables direct applicability of the findings in the spatial planning and rural context. This choice of unit of analysis is in line with JRC recommendations for land use analysis in small states, where NUTS-3 is too coarse to see intra-state differentiation [

20,

32,

33,

34]. The obtained indicators and spatial layers are presented in the form of tables and thematic diagrams in the next chapter, which enables a comparison of the degree of digital activity and land utilization among municipalities and their further connection with the concept of “smart territorial restructuring”.

To strengthen the credibility of the assumed causal relationship between agricultural digitalization and land revitalization, an additional quasi-experimental design using Propensity Score Matching (PSM) was incorporated. Municipalities with a high level of digital activity were defined as “treated”, while municipalities with a low level of digitalization served as a “control” group. The PSM enables equalization of units according to key characteristics (share of agricultural land, demographic structure, altitude, accessibility to markets), which reduces the influence of confounding factors and increases the precision of the assessment of differences between groups. The PSM helps to distinguish how much progress in land use can be attributed to the actual application of digital solutions, rather than the pre-existing development advantages of certain areas. A conceptual Difference-in-Differences (DID) framework has been established that will enable a longitudinal assessment of effects in the period 2024–2028, during the implementation of digital measures foreseen in the CAP Strategic Plan Cyprus 2023–2027. The DID method enables the comparison of changes in treated municipalities with changes in control municipalities over time, thus providing an assessment of the net effect of digital interventions on the reduction in abandoned areas and the strengthening of territorial cohesion. Combining PSM and DID methodology contributes to the transition from correlative analysis to empirically based causal interpretation of findings. This confirms that digital agriculture, if it is institutionally supported and spatially focused, can be a trigger for the spatial reactivation of rural communities and the establishment of more sustainable patterns of land use.

4. Results

The analysis of the CORINE Land Cover (CLC) spatial database for the period 2018–2024 showed significant changes in the way agricultural land is used in Cyprus. In the central and eastern parts of the island, especially in the area of the municipalities of Larnaca, Paralimni and Dromolaksia, a stable or slight increase in arable land was recorded. In the western and mountainous areas, especially in the Troodos zone, patterns of land abandonment and fragmentation have been observed. Compared to 2018, the total area of actively used agricultural land in rural areas decreased by about 7%. The share of land classified as “heterogeneous agricultural land” increased by approximately 12%, indicating a shift from intensive to partial agricultural use. These trends are in line with the analysis of the JRC LUISA platform, which predicts that the island economies of the Mediterranean (Cyprus, Malta, Balearic Islands) will have the highest relative risk of land abandonment in the EU by 2030, primarily due to demographic pressure and labor shortages in agriculture [

45,

46]. The spatial patterns also confirm the findings of the study by Djuma et al. [

2], who documented a significant withdrawal of agricultural activity on the Troodos mountain terraces, which increases the risk of erosion and reduces landscape cohesion. When spatial layers of CLC data are overlaid with indicators of digital readiness of agriculture, a clear pattern of association between the degree of digital activity and land use emerges. The digital readiness composite index was calculated using indicators from the CAP Strategic Plan Cyprus 2023–2027, and Agricultural Research Institute [

9] data. The analysis shows that municipalities with a greater number of precision agriculture projects, digital advisory services and infrastructure for smart irrigation record a significantly lower degree of abandoned land. The results are presented in

Table 3, which systematizes the three categories of municipalities according to the degree of digital adoption and average values of land use.

Table 3 clearly confirms the existence of a positive correlation between digital activity and agricultural productivity. Municipalities with high digital adoption retained an average of 27% higher share of actively used land compared to municipalities with a low level of digitalization. Spatial autocorrelation results (Moran’s I = 0.42;

p < 0.01) confirm the grouping of municipalities according to the degree of digital activity, which indicates the creation of “digital resilience clusters” in the eastern and southern parts of the island, especially around Larnaca and Paralimni. These results are in agreement with studies documenting that digital innovations in agriculture contribute to reducing the risk of land abandonment and increasing the resilience of rural economies [

10,

21]. The findings also confirm that digital adoption has a spatial dimension and appears in clusters where local institutions are more active, infrastructure is better and the availability of e-services is greater. ITU FAO [

34] confirms that countries with digital readiness achieve faster adaptation to climate and market changes because data becomes a decision-making tool, not just technical assistance. A detailed spatial analysis using LISA methods showed that high-high clusters of digital activity are concentrated in the coastal areas of eastern and southern Cyprus, while low-low clusters are dominant in the mountainous areas of Troodos and northern municipalities. Such spatial differentiation has direct implications for development policies: regions with a lower degree of digital adoption simultaneously show a greater risk of demographic depopulation and lower investment in infrastructure, thus confirming the connection between digital infrastructure, economic activity and demographic flows [

20,

61].

Regional differences in the application of digital technologies in agriculture in Cyprus show a consistent spatial pattern, with more advanced digital approaches spatially concentrated in the eastern and southern coastal municipalities, while the mountainous cores of the Troodos show the lowest intensity of digital transformation. This heterogeneity is not just a statistical phenomenon, but is based on deep-rooted structural and socio-economic factors. Coastal areas are characterized by better developed communication and transport infrastructure, greater accessibility to markets and the presence of institutions that mediate knowledge transfer, advisory services, university partners and technology centers. In such an environment, digital innovations are established as a logical continuation of previous modernization processes, so local producers are more involved in programs of precision agriculture, smart irrigation projects and digital value chains. In contrast, Troodos and surrounding mountain municipalities face systemic constraints, long-term depopulation, fragmented land structure, dominance of traditional small farms, difficult access to investment and limited institutional support. Digitization in such areas does not develop through network diffusion, but most often as a short-term pilot intervention, which rarely develops into a sustainable practice. The combination of geographic isolation and weak institutional mediation slows the adoption of technology and reproduces already existing developmental differences. These structural differences are clearly reflected in the outcomes of spatial transformation: a more extensive presence of digital solutions in coastal municipalities results in a greater share of actively used land and more stable agricultural income, while in mountain communities the risk of agricultural land abandonment and further weakening of the local economy increases. Digital resilience is therefore not distributed evenly, but gravitates towards places with already existing development advantages, thus deepening the gap between “connected” and “backward” rural areas. This spatial concentration of benefits from digital policies indicates the danger of creating “digital islands of prosperity” versus “islands of marginalization”, which has direct implications for territorial cohesion. If we do not intervene with targeted development measures in mountainous areas, there is a real threat that the digital transformation, instead of reducing regional differences, will become a new source of territorial inequalities. That is why it is necessary to recognize Troodos not as a periphery, but as a strategic zone in which digitization should be an instrument of revitalization and not an indicator of backwardness in rural development policies. These findings confirm that spatial differences in digital practice in Cyprus are not a passing phase, but a structural pattern that requires a differentiated territorial policy, in which digital solutions must be adapted to the specific identity and needs of each rural region.

Municipalities involved in projects such as Smart Irrigation Control for Citrus Production (Larnaca, 2023) and Digital Vineyard Monitoring System (Limassol, 2022) reported productivity increases of 10–15% and reductions in irrigation water costs of 18–25% [

9]. These results show that the effects of digitization are multiple—not only economic, but also environmental and social, as they enable better control over resources and reduce dependence on seasonal labor. Similar projects in Italy and Spain [

31,

36] confirmed the same pattern: digital technologies strengthen the resilience of local communities and accelerate the process of territorial cohesion. The obtained data confirm the initial hypothesis that digital agriculture in Cyprus functions as an instrument of territorial integration and rural revitalization. The space in which digital technologies are adopted shows greater functional connectivity and economic resilience, which is fully in line with the concept of smart territorial restructuring developed in this paper. Digital agriculture becomes a bridge between technological innovation and spatial planning, connecting local communities, land management and sustainable development policies.

This finding is especially important in the context of the EU Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas (2021–2040), which emphasizes that the digital transition should serve to reduce regional differences and create resilient territories. Cyprus, as a small island country with pronounced geographical contrasts, provides clear evidence of how a combination of digital tools and smart spatial planning can reverse the negative trends of depopulation and land degradation. The results indicate that digital agriculture is not only a technical innovation, but also a strategic mechanism of territorial policy that can synchronize local, national and European development goals.

4.1. Integrating Digitalisation into Territorial Cohesion

The research results show that digital agriculture in Cyprus goes beyond a purely technological function and becomes an important mechanism of territorial integration. The identified “digital resilience clusters” in the eastern and southern regions confirm that the spatial concentration of innovations leads to better resource management, more stable production and greater connectivity between rural and urban areas. Thus, digitalization is shown to be a tool for bridging development inequalities, especially in island states with pronounced geographical contrasts [

19,

58]. At the European level, these findings are fully aligned with the policies of the EU Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas (2021–2040), Territorial Agenda 2030 and Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which recognize the digital transition as a key element of spatial cohesion [

38,

50,

55]. Through the integration of digital tools in the planning of land, water and agricultural value chains, Cyprus can be seen as an experimental model for “micro-territorial digital transformation”, which brings together the spatial, social and economic dimensions of development [

20,

34].

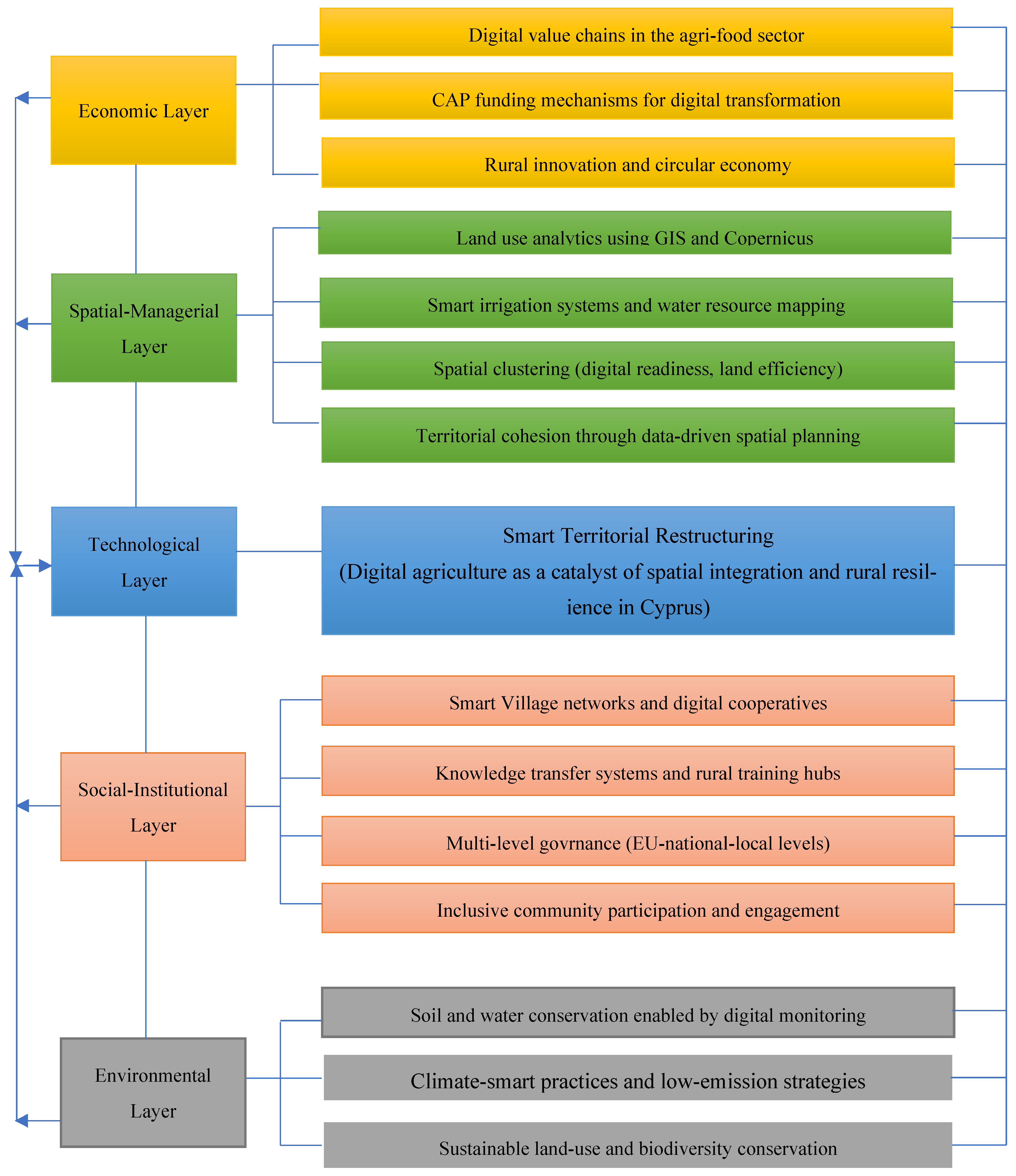

The conceptual framework Smart Territorial Restructuring Framework was formed, which unites five complementary dimensions of development, technological, spatial-management, social-institutional, economic and ecological. It shows how digital agriculture becomes an integrative system that simultaneously connects innovation, communities and natural resources into a unique mechanism of territorial resilience. This framework is shown in

Table 4.

The five dimensions of the presented framework do not act as isolated elements, but as interconnected phases of a unique transformation process. Technological innovations in agriculture, such as sensor systems, UAV monitoring and GIS analytics, create precise spatial information that directly affects the way land and water resources are managed. When such spatially based evidence becomes an integral part of local planning and decision-making, management practices are improved and the transition towards decentralized spatial management is encouraged. On this basis, institutional and social structures are strengthened, local innovation networks, digital cooperatives and participatory mechanisms are formed that enable data to be used in the collective interest of the community. This institutional shift opens up space for economic changes: digitization of growth into the creation of new value chains, access to advanced markets and diversification of the rural economy. Economic empowerment is necessarily preceded and followed by more responsible management of resources, pressure on land and water is reduced, soil protection is improved and degradation is prevented, which confirms that the digital transition contributes to the ecological resilience and climate stability of rural areas. At the same time, environmental constraints, especially in areas with water deficits and high erosion pressures, are driving the process back to the technological sphere, generating the need for additional innovations. This creates a closed, self-reinforcing loop in which technology, space, institutions, economy and ecology support each other and enable digital agriculture to function as an integrated mechanism of territorial resilience and revitalization.

The presented land cover map of Cyprus further shows the complexity, spatial dispersion and multi-layered land use structure of the island (

Figure 1). The visual representation builds on the conceptual framework from

Table 4, supporting the thesis of a fragmented and multifunctional rural space that represents a challenge, but also an opportunity for digital transformation in agriculture. Based on the cartographic data, different land cover categories are clearly identified, including artificial surfaces, arable and permanent crops, forest complexes, pastures, wetlands and degraded lands, confirming the need for a fine-grained data-driven territorial approach. Agricultural land and permanent crops noticeably dominate the coastal areas and lowlands, while the central Troodos mountain massif is characterized by dense forest landscapes, areas of semi-natural vegetation and less accessible lands. This spatial configuration enables a better understanding of the factors that encourage the accelerated development of digital agriculture in economic hotspots, where the presence of agricultural activity is accompanied by infrastructure availability, market orientation and institutional support. The map indicates territories that are vulnerable to land abandonment processes, in mountainous and less accessible regions. There is a decrease in agricultural activity and greater exposure to environmental and demographic challenges. These municipalities require interventions that combine the conservation of natural resources with incentives for digital inclusion and sustainable land use. The map not only shows the current structure of land use, but also confirms the strategic importance of territorial planning and technological adaptation in accordance with the identified patterns. The visual complexity of the map fully corresponds with the findings from

Table 3 and

Table 4, and additionally strengthens the conclusions about the need for differentiated, smart solutions in the digitalization of the agrosystem in Cyprus.

4.2. Technological and Spatial Integration

The technological and spatial dimensions form the basis of the transformation of rural areas. The implementation of IoT sensors, GIS platforms and satellite monitoring enables precise resource management, which is crucial in Cyprus due to chronic water deficit and fragmented land [

9,

21]. Such systems enable real-time monitoring of moisture and productivity, so decision-making no longer relies only on the farmer’s experience, but also on quantified data. The integration of digital tools into spatial planning allows land policy and digital transformation to be viewed as a single process. The application of GIS and LULC analysis allows local authorities to precisely identify zones at risk of abandonment, to plan the restoration of terraced areas and to model water use in real time [

41]. This is in line with the Digital Europe Program [

57] and the Smart Villages Strategy, which promote the territorial application of digital solutions and the transition from reactive to preventive management of rural space [

56]. Technological and spatial integration become a key prerequisite for the formation of “digital landscapes”—areas where infrastructure, natural resources and data are used in sync with the aim of sustainable land use.

4.3. Social and Institutional Resilience

The social-institutional dimension of digital transformation indicates that its success does not depend primarily on the technologies themselves, but on society’s ability to accept them, adapt them to their own needs and manage them effectively. The Cyprus experience clearly shows that the key drivers of digitization are not tools, but people, local capital, knowledge, education and community cooperation. Initiatives like Smart Villages and Digital Cooperative Networks create environments where farmers, researchers and local authorities operate within shared digital ecosystems, developing new forms of collective intelligence and mutual learning in rural areas [

61,

62]. Municipalities that have established cooperation with universities and established local innovation incubators, such as Limassol and Larnaca, show a faster pace of digital transition and greater resilience to economic and social changes. The same is noted in Italy, where rural communities that have included academic partners in Smart Villages networks achieve a higher rate of innovation [

36]. The role of institutional capital thus becomes central: without it, the digital infrastructure remains unused and social sustainability is limited. In a theoretical sense, this confirms that digital agriculture must be part of a broader concept of rural innovation policy, in which local institutions are the bridge between technology and community.

The economic dimension of digital transformation is expressed through the creation of new value chains and the encouragement of innovative business models in rural areas. Programs funded through the CAP Strategic Plan 2023–2027, Horizon Europe and the Digital Europe Program enable small producers to develop startup initiatives in the areas of sensor analytics, agro-robotics and digital markets [

56,

62]. Digital markets and online platforms connect producers directly with consumers, reducing the role of intermediaries and increasing profitability. The new digital economy of rural areas is formed, in which the principle of circular economy and local development is combined with innovations [

19,

34]. Such models increase the resilience of the rural economy and reduce dependence on seasonal production, while at the same time opening up space for employment of young people and professionals in the fields of agronomy, information technology and sustainable design of supply chains. The Cyprus example shows that, although the scope of agriculture is limited, digital innovations can create multiplier effects in local communities, from the development of new services, to the formation of agro-technical advisory centers and the export of knowledge.

4.4. Environmental and Climate Implications

The ecological dimension of digital transformation reveals that digital technologies are a mechanism of ecological compensation. Smart irrigation systems, moisture sensors and digital evapotranspiration models make it possible to reduce water consumption by 20–30%, while preserving yields and soil stability [

35,

36]. The use of GIS maps and remote sensing reduces erosion and enables precise monitoring of soil conditions, especially in the Troodos mountain areas where degradation has a long-term impact on ecosystems. Thus, digitization directly contributes to the goals of the European Green Deal (2020) and the EU Soil Strategy 2030, which emphasize the need for digital transformation to become an instrument of ecological renewal and climate resilience. Digital agriculture creates the basis for data-driven climate planning, where spatial information is used to model emissions, water balance and biodiversity. In Cyprus, this has a special weight because each unit of land has multiple functions, agricultural, ecological and landscape.

4.5. Policy and Strategic Implications

The findings of the research have direct implications for the national policies of spatial and rural development of Cyprus. Digital agriculture can become a central pillar of the new Territorial Cohesion Strategy, provided it is linked to land planning, water resources and education policies. Recommended:

Establishment of the Digital Agricultural Observatory Cyprus, as an integrated database on land, water and digital interventions, which would also serve as analytical support for the Ministry of Agriculture and local authorities.

Smart Terraces program, intended for the restoration of mountainous and abandoned lands through a combination of digital surveillance and financial incentives.

Strengthening Smart Village Hubs in mountainous and remote regions for farmer training and participatory planning, with support from ARI and universities.

Priority investment in rural broadband infrastructure, because there is no real inclusion without digital access.

These recommendations are fully aligned with the objectives of the EU Territorial Agenda 2030, CAP 2023–2027 and the Digital Europe Programme, thus ensuring that digital agriculture becomes an instrument of inclusive, spatially balanced and climate-resilient development in Cyprus [

20,

58]. The proposed framework can serve as a model for other Mediterranean and island EU member states, which face similar challenges of combining digital modernization and preserving territorial connectivity.

Figure 2 shows how digital agriculture functions as an integrated mechanism affecting multiple dimensions of rural space. In the gray zone, on the lower level, there are ecological elements related to the preservation of soil, water and biodiversity through digital monitoring and climate-smart practices. Above that, the orange level includes socio-institutional processes, including digital cooperatives, knowledge transfer, management coordination and involvement of local communities. The central blue segment represents the technological core of the system—Smart Territorial Restructuring—through which digital innovations become the driver of spatial and economic transformation. The green level illustrates the spatial management dimension: GIS and Copernicus analytics, smart water management and data-driven spatial cohesion. At the top of the diagram, the yellow economic layer shows how technical and spatial advances result in new digital value chains, innovation and financing that empower the rural economy. The vertical flow of effects and feedback loops between layers show that improvement in one dimension creates positive changes in others, making digital agriculture a key instrument of territorial cohesion and resilience of rural communities in Cyprus.

5. A Framework for Smart Territorial Restructuring

This chapter presents an integrated conceptual framework developed as a synthesis of empirical and spatial findings presented in previous chapters. It illustrates how digital agriculture acts as a driver of territorial restructuring and rural revitalization in Cyprus. The model connects four interrelated functional layers: data and spatial inputs, digital agriculture and decision-making, territory and community management, and sustainable development outcomes. Each layer corresponds to a phase of the process that connects technological innovation with spatial planning and rural policies. The first layer is connected with data and spatial inputs including the actual data sources used in the research: CORINE and Copernicus land use layers, agriculture and water resources statistics of the Ministry of Agriculture of Cyprus, and digital readiness indicators from the CAP Strategic Plan Cyprus 2023–2027 and the JRC report These data form the basis for identifying underutilized land and assessing the digital potential of rural areas (

Figure 3).

The second layer, digital agriculture and decision-making includes technological components such as precision agriculture, smart irrigation, IoT sensors and digital advisory systems developed by the Agricultural Research Institute (ARI). These technologies enable data-driven decision-making and provide support to producers and municipalities through real-time analytics. The third layer, governance of territory and communities refers to institutional and social mechanisms that connect digital technologies with local governance. A key role is played by networks of Smart Village initiatives, digital cooperatives and multi-level governance that connects European policies (CAP, Green Deal) with national and municipal programs. In this way, digital solutions become part of the local decision-making system, which increases the level of participation and the capacity of the community.

The fourth layer—Sustainable outcomes integrates all the previous components into concrete results: more efficient use of land, stronger territorial connectivity, resilience to climate change and more inclusive rural development. The presented framework shows that digital agriculture is not only a modernization of production, but a complex mechanism of territorial integration. The model emphasizes the vertical dimension—the transition from data to spatial policy, and the horizontal dimension—the connection between producers, local authorities and European institutions. This means that information collected through digital technologies (IoT sensors, GIS analysis, AI models) becomes the basis for creating plans and land use decisions. At the same time, local and national institutions adjust their programs and investments in accordance with this data, thus forming a feedback loop between innovation and management. This framework provides a realistic mechanism for reconciling economic, environmental and territorial objectives in the context of Cyprus, where land fragmentation, depopulation and limited water resources are key challenges. Smart territorial restructuring becomes a strategic bridge between the digital transformation of agriculture and balanced spatial development.

The development of digital agriculture in Cyprus does not take place spontaneously, but within a complex system of institutional coordination and information exchange. This process includes three levels of governance, European, national and local, which are interconnected through funding, regulation and feedback mechanisms. Digital innovations such as precision agriculture, smart irrigation and GIS mapping require a clear flow of data, from the strategic guidelines of the European Union, through the national institutions that implement them, to end users, producers and rural communities. The key assumption of this research is that digital agriculture becomes effective only when it is supported by institutional mechanisms that connect technical innovations with spatial and development policies. This enables the data collected at the local level (via sensors, satellites or digital services) not to remain isolated, but to be part of a wider decision-making system. The Cyprus model is based on the integration of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) policies, technological projects implemented by the Agricultural Research Institute (ARI), and initiatives of local communities gathered in Smart Villages networks. This multi-layered system enables technological and regulatory innovations to be transferred from EU strategic documents to everyday practice in rural areas.

Figure 4 shows how data, resources and decisions move between the three institutional levels and how a feedback loop is formed between policy, science and practice. Each level has a specific function and a set of institutions, but their connection is crucial for achieving a sustainable digital transformation of agriculture.

The role of digital agriculture in the transformation of rural space in Cyprus is not based only on technical innovations, but on the creation of a functional network in which spatial information becomes the driver of changes in land management and development strategies. The first step in that process is to convert satellite and IoT data into operational knowledge that can be applied in everyday agricultural practice, which increases productivity and resource efficiency. However, data by itself is not enough if there are no institutional mechanisms that transfer it from the technological framework to the decision-making space. This is why in the model the role of local structures of digital cooperatives, Smart Village networks and municipal development departments, which connect producers with national and European programs, is key. Digital tools are becoming part of production planning, creating rural investments and making decisions about land use. This vertical and horizontal integration allows the use of digitization to translate into measurable development outcomes: reduction in abandoned areas, better spatial and market connectivity of villages, reduction in vulnerability to climatic extremes and strengthening of local economy. The process thus becomes cyclical, feedback loops allow new information from production and space to constantly direct policies. The model shown in the diagram confirms that digital agriculture acts as a mechanism of territorial cohesion, as it transforms technical progress into sustainable spatial management, thus simultaneously addressing the demographic, infrastructural and environmental challenges that Cyprus faces. Digital agriculture is not only a modernization tool, but the basis of a new development paradigm in which data and spatial policies are coordinated with each other in order to ensure a long-term vital and competitive rural space.

This

Figure 4 shows that the success of digital agriculture in Cyprus depends on the ability to move data and policies between different levels of governance. EU institutions provide funds and standards, national institutions translate them into concrete programs and technological projects, while local communities provide feedback and field validation. Such a structure enables double integration—vertical (between levels of government) and horizontal (between communities). This creates a closed loop of innovation and management, in which any new data or technological initiative is fed back into the system as a basis for updating policies and plans. The Cyprus institutional model shows that sustainable digital transformation of agriculture depends on effective vertical integration (between policies and practices) and horizontal cooperation (between local actors). The European level sets the strategic framework and provides funds, the national level translates them into operational programs, and the local level turns them into real results.

This system creates conditions for digital agriculture to be not only a technological process, but an instrument of territorial restructuring that connects spatial, economic and social aspects of rural development. In this sense, the presented diagram is not only a scheme of communication between institutions, but also a model of the functioning of the integrated digital policy within the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union.

The added value of this institutional model is reflected in its ability to continuously harmonize long-term European priorities with local production realities. This avoids the typical problem in agricultural policies, when innovations remain limited to pilot projects without real impact on the management of space and resources. Instead, digital solutions in Cyprus become an integral part of local development strategies, because institutions at all levels act in one coordinated cycle. The model thus enables the information obtained from the field about soil productivity, water availability, climate pressures or producer interest to be immediately transferred to decision makers, who direct future investments accordingly. This kind of feedback turns digital agriculture into a tool for proactive management of rural development, where decisions are no longer made based on average statistics, but on precise spatial data. In the context of Cyprus, which faces pronounced land fragmentation, limited water potential and marked regional differences in agrarian activity, this institutional architecture has a special importance. It enables targeted interventions, directing digital projects precisely to the communities that lag the most in terms of efficiency and connection to the market. Thus, the digital transformation turns into an instrument of territorial solidarity, because it reduces development inequalities and strengthens the role of rural areas in the national economy.

6. Discussion

This chapter interprets the research findings through the prism of modern theories about digital transformation, territorial cohesion and sustainable development of rural areas. The results of previous analyzes indicate that digital agriculture in Cyprus goes beyond the scope of technological innovation and functions as an integrative mechanism of territorial resilience. The discussion therefore includes four main conceptual aspects: spatial transformation, institutional integration, social adaptation and the ecological and political implications of the digital transition.

The findings confirm that the process of digitization of agriculture leads to the spatial reorganization of rural areas. Digital clusters in the eastern and southern regions of Cyprus are not a random phenomenon, but the result of the synergy of infrastructure, knowledge and institutional support. This concentration of digital activities is important for the “smart clusters” model that the European Commission recognized as a key factor of territorial cohesion in smaller member states [

20]. Cyprus can be seen as a micro-model of European rural transformation. The traditional development patterns rely on physical capital and the digital economy is shaping a new “geometry of space” based on data flows, access to knowledge. This spatial configuration supports the thesis that digital technologies act as catalysts of territorial justice, as they enable communities to access markets, information and innovation [

19,

58]. Spatial analyzes show that digitally active municipalities are both more economically stable and more ecologically resilient, which confirms the connection between digital infrastructure and multifunctional land use. The digital transformation of agriculture in Cyprus shows that its success depends on a multi-layered institutional system that connects the European, national and local levels. Mechanisms such as the CAP Strategic Plan 2023–2027, the Smart Villages initiative and the ARI Cyprus projects operate as parts of a unique “digital governance ecosystem”. This system allows data collected through sensors and GIS platforms to be integrated into spatial planning and rural development policies. Such institutional connectivity illustrates the concept of “reflexive territorial cohesion”, in which decisions are made based on feedback between policy and practice [

34,

62]. The Cyprus model shows how digital agriculture can become an instrument of decentralized but coordinated management that simultaneously respects local specificities and European sustainability goals.

Technological progress alone is not enough, social adaptation and knowledge remain key success factors. Digital agriculture requires a new division of roles between farmers, institutions and technological intermediaries. In Cyprus, municipalities that have developed educational and research partner networks have achieved a higher degree of adoption of digital solutions and greater self-sustainability. This confirms the thesis of Gaál et al. [

61] that the successful digitization of rural communities is based on horizontal cooperation and not exclusively on technological investments. The social component of the digital transition contributes to the creation of the collective intelligence of rural areas, the community’s ability to use data, predict risks and make joint decisions. The Cyprus experience shows that digital transformation is not only an infrastructural, but also a cultural change, as it changes the way communities think, connect and plan their future. The ecological aspect of digital agriculture in Cyprus shows how smart technologies can serve as an instrument of climate resilience. Smart irrigation, satellite soil monitoring and digital resource monitoring reduce pressure on ecosystems and increase water use efficiency [

35,

36]. Thus, the digital transition contributes not only to productivity, but also to ecological renewal, in accordance with the European Green Deal (2020) and the EU Soil Strategy 2030. These findings confirm the need for an integrated digital-environmental strategy. Instead of viewing digital agriculture as a technological sector, it needs to become an integral part of the national territorial cohesion policy, with priorities for investment in knowledge, data and spatial management.

The Cyprus model shows that digital agriculture can function as a system of interconnected policies, where technological innovation flows into spatial integration, social resilience and environmental sustainability. This multi-layered transformation suggests that the future of rural development in Europe is determined not only by the quantity of resources, but by the quality of data and the ability of institutions to use it. Smart territorial restructuring is not only a local strategy of Cyprus, but a potential model for other Mediterranean and island economies facing similar challenges, a combination of climate constraints, land fragmentation and demographic pressure. Through the participation of local communities in the Smart Rural 27 initiative as well as through the pilot projects of ARI in precision agriculture, Cyprus is positioning itself as a test environment for European digital transition policies in rural areas. Research in other Mediterranean countries shows similar spatial patterns, more digitally advanced communities achieve greater resilience and lower risk of land abandonment, just as the results indicate for the eastern and southern municipalities of Cyprus. This confirms that digital solutions in Cyprus do not work in isolation, but as part of a wider European territorial cohesion strategy, where small geographical areas are used to test innovative approaches to rural development. Thus, Cyprus, although geographically small, becomes a laboratory of European digital cohesion.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although the research results provide strong evidence that digital agriculture in Cyprus functions as a mechanism of territorial cohesion and rural revitalization, certain limitations deserve attention. First of all, the availability of data on digital interventions in agriculture and their territorial distribution is still limited. Most of the relevant information comes from individual projects, such as the Smart Villages initiative, the Agricultural Research Institute’s pilot program and CAP-funded interventions, which makes it difficult to form a single and standardized basis for a quantitative assessment of digital adoption. Such fragmentation of data, characteristic of small island states, reduces the possibility of fully measuring the effects of digital transformation at the micro-level, especially in the mountainous and isolated municipalities of Troodos. Another limitation relates to the spatial resolution of the data used. Although the CORINE Land Cover and Copernicus databases allow good comparability within the EU, their 100 m resolution does not allow precise detection of micro-changes, such as succession on abandoned terraces or partial use of agricultural plots. Future research should combine high-resolution satellite sources with local geo-referenced data and field validations to obtain a more detailed picture of the spatial transformation process. The third challenge relates to the social dimension of the digital transition. Spatial and infrastructural indicators are clearly defined, but the influence of educational, cultural and institutional factors on the adoption of technologies is still not sufficiently explored. The level of digital competences, trust in technology and the role of local institutions represent variables that can influence the success of digital transformation.

A understanding of these factors could enable the development of an integrated model that links technical readiness with social adaptability and institutional trust, making the digital transition a technological, and socially sustainable process. In future research, it is also necessary to test the transferability of the “smart territorial restructuring” concept to other Mediterranean and island EU member states, such as Malta, Greece and Italy. Such a comparative analysis would enable the formation of a regional framework for measuring the digital resilience of territories and contribute to the creation of a single index “Digital-Resilient Territories”. Thus, the Cypriot model could be confirmed as a reference point for research on digital cohesion, rural sustainability and spatial transformation in European development policies. Despite the aforementioned limitations, this paper lays a solid foundation for further multidisciplinary analyzes that integrate the spatial, technological and social aspects of the digital transition, while offering an operational model applicable beyond the national borders of Cyprus.

Although the analysis offers a clear insight into the spatial dynamics of digital agriculture in Cyprus, it is important to point out that the results rest on specific theoretical and methodological assumptions that condition their applicability. A quantitative approach based on correlative methods does not allow for the complete elimination of the influence of confounding variables, especially those related to human capital, institutional culture and the community’s willingness to accept innovations. These factors are necessary to transform digital equipment into sustainable practice, but could not be systematically managed at this stage of the research due to data availability limitations. The applied experimental framework assumes relatively similar initial conditions among the observed municipalities, which in the context of Cyprus is not fully fulfilled. Differences in topography, access to markets, age structure of the population and degree of institutional organization may partially influence the identified spatial patterns of digital resilience. It is necessary to approach causal claims with caution and view them as indicators of probable development mechanisms, and not as a deterministic conclusion.

The analysis of digital readiness predominantly relies on infrastructure and investment indicators, while more complex elements such as social trust in digital tools, producer motivation or local organizational capacities remain insufficiently quantified. Although supplemented with dynamic indicators, the measures used still primarily reflect the current scope of technology application, while institutional adaptation processes require a longer time horizon.

The findings of this research represent a starting point for a better understanding of the territorial effects of digital agriculture in small island states, but their generalization must be performed while respecting the mentioned methodological limitations. Future research should include a longitudinal approach, a more detailed assessment of institutional and social factors, as well as more advanced causal models in order to more precisely determine which mechanisms lead to true territorial cohesion within the digital transition of rural spaces.

7. Conclusions

This research showed that digital agriculture in Cyprus has the potential to reshape the very logic of territorial development. It is no longer just an instrument of technological modernization, but has become the basis of a new paradigm of spatial and social cohesion. In a small island nation like Cyprus, where spatial inequalities, land fragmentation and demographic decline are historical challenges, the digitization of agriculture opens up the possibility to connect what has been separate: economy, community and space. Thus, the digital transition takes on a deeper meaning: it becomes a way to redefine rural identity through knowledge, data and innovation.

Empirical findings indicated that regions with a higher concentration of digital activities and institutional support managed to maintain active land use, increase productivity and strengthen local resilience. Those spatial clusters of digital activity represent not only technical progress, but also the emergence of new forms of territorial cooperation, in which decisions are made based on real data and with the participation of the community. Digital infrastructure, GIS systems and smart sensors have thus become the basis for a new form of spatial justice, as they enable remote rural areas to obtain equal access to resources, information and investments. This transformation has multiple implications. On the economic level, it opens up space for diversification and the strengthening of local value chains; on the social level, it creates opportunities for education, employment and the return of young people to rural areas; on the ecological side, it enables every decision on land use to be based on a sustainable balance between productivity and resource protection. Digital agriculture, therefore, is not only about increasing yields, but creates a new socio-ecological contract between man and space, based on data, knowledge and responsibility.

For policy makers, the key message emerges from the very logic of territorial integration: the digital transition must be simultaneously technological, institutional and cultural. Without local involvement, even the most advanced systems will have no real effect on the ground. That is why digital agriculture must be accompanied by investments in education, rural innovation centers, Smart Village networks and institutional bridges between ministries, municipalities and research organizations. Sustainable digitization depends not only on the speed of the Internet, but on the ability of the community to turn digital information into a common good.

The Cyprus case shows that even a small country can become a model of territorial resilience if it connects science, technology and local practice in a unified decision-making system. In this sense, “smart territorial restructuring” is no longer just a theoretical concept, but an applicable strategy that combines spatial data, digital agriculture and participatory governance. This approach not only changes the way in which food is produced, but also the way in which the territory is understood, as a living, adaptive system in which every decision has spatial, social and ecological resonance. Digital agriculture in Cyprus becomes a mirror of the future European model of rural development: integrated, fair and sustainable. Its strength lies not in technology itself, but in the ability to connect people, knowledge and space in a shared vision of balance. This work does not end there, but opens up a new phase of research, one in which digital transformation becomes a starting point for thinking about a broader question: how to build territorial systems that learn, adapt and last.