Towards Strategic Planning for Ephemeral Living Stream Drainage Upgrades

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Public Open Space Provision

1.2. Drainage Networks

1.3. Living Streams

Origins of Living Streams

1.4. The Functions of Living Streams

1.5. The Problem of Opportunistic Decision Making

1.6. The Research Question

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study

The Drainage for Liveability Program

2.2. The Drainage for Liveability Delphi Survey

2.2.1. The Stage 1 Survey

2.2.2. The Stage 2 Survey

2.3. Suitability Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Delphi Survey Results

Expert Survey Panel

3.2. Overall Criterion Ratings

3.3. Qualitative Commentary

3.3.1. Areas with Limited Public Open Space Availability (1st Highest Priority)

3.3.2. Areas with Low Urban Forest Canopy Cover (2nd Highest Priority)

3.3.3. Areas with Higher Urban Density (3rd Highest Priority)

3.3.4. Areas with High Land Surface Temperatures (4th Highest Priority)

3.3.5. Areas with Aboriginal Heritage (5th Highest Priority)

3.3.6. Areas with Shallow Depth of Groundwater (6th Highest Priority)

3.3.7. Areas That Have Populations Experiencing High Levels of Psychological Distress (7th Highest Priority)

3.3.8. Areas with Threatened Ecological Communities (8th Highest Priority)

3.3.9. Areas with Water Requiring Nitrogen and Phosphorus Reduction (9th Highest Priority)

3.3.10. Areas That Have Populations Experiencing Socio-Economic Disadvantage (10th Highest Priority)

3.3.11. Areas Which Are Zoned Residential (11th Highest Priority)

3.3.12. Areas Which Have Populations Engaging in Low or No Exercise (12th Highest Priority)

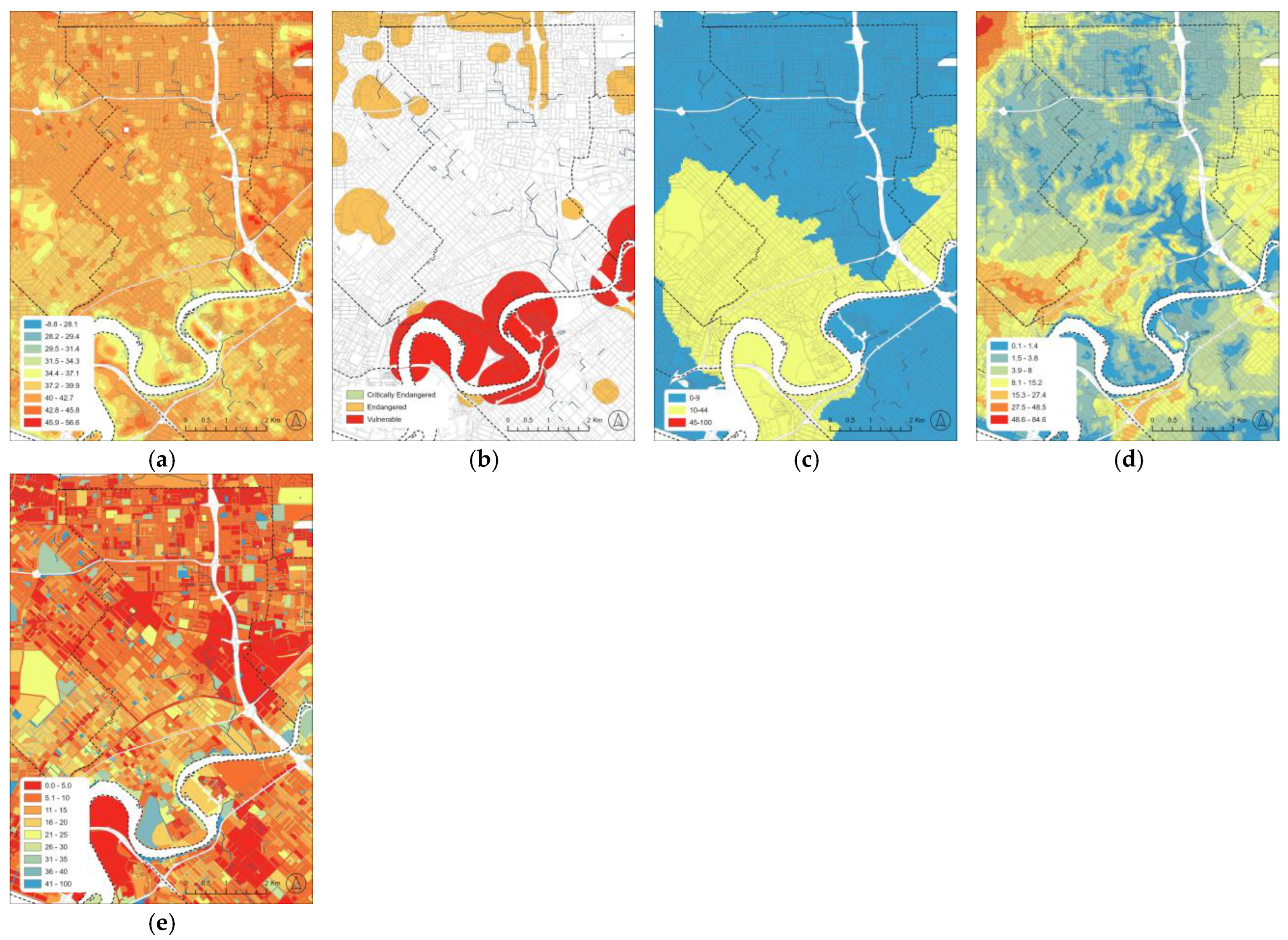

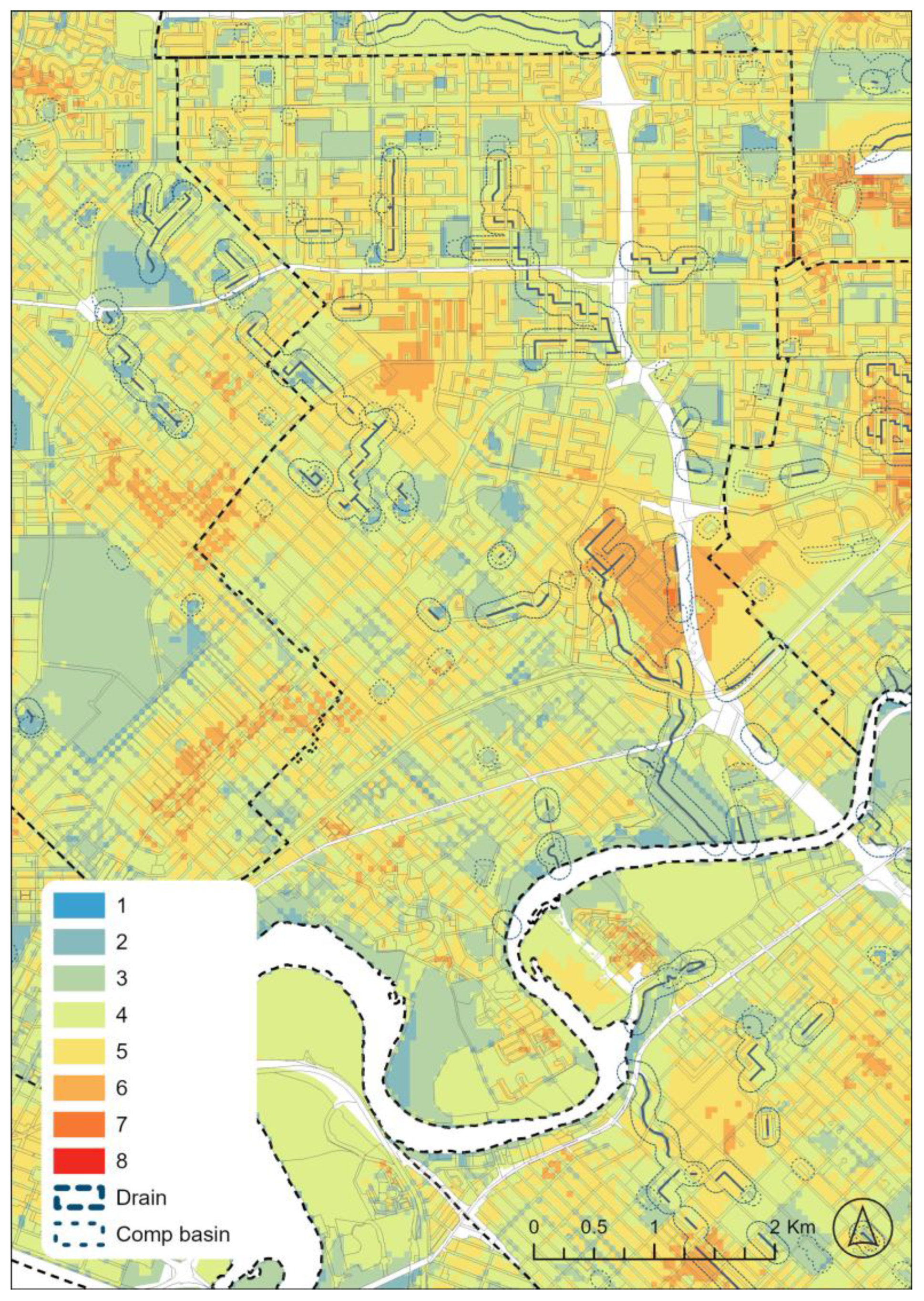

3.4. Suitability Analysis Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Findings in Relation to the Literature

4.2. Living Streams: A Misnomer in the Perth Context

4.3. The Dominance of Spatial Criteria

4.4. Challenges in the Implementation of Living Streams

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byrne, J.; Sipe, N. Green and Open Space Planning for Urban Consolidation—A Review of the Literature and Best Practice. In Urban Research Program; Griffith University: Brisbane, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bolleter, J.; Ramalho, C.E. The Potential of Ecologically Enhanced Urban Parks to Encourage and Catalyze Densification in Greyfield Suburbs. J. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 9, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, C.E.; Bolleter, J. Greenspace-Oriented Development: Reconciling Urban Density and Nature in Suburban Cities; Springer: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Iftekhar, M.S.; Pannell, D.J. Developing an Integrated Investment Decision-Support Framework for Water-Sensitive Urban Design Projects. J. Hydrol. 2022, 607, 127532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. Integrated Urban Water Management—Why a Good Idea Seems Hard to Implement; Productivity Commission: Docklands, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pen, L.; Majer, K. Drains Versus Living Streams. In How Do You Do It? Water Sensitive Urban Design Seminar 1994; Proceedings; Institution of Engineers: West Perth, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, E.S.; Palmer, M.A. Restoring Streams in an Urbanizing World. Freshw. Biol. 2007, 52, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolleter, J. Living Streams for Living Suburbs: How Urban Design Strategies Can Enhance the Amenity Provided by Living Stream Orientated Public Open Space. J. Urban Des. 2017, 23, 518–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolleter, J. Green Dream: Examining the Barriers to an Innovative Stormwater and Public Open Space Structure Plan on Perth’s Suburban Fringe. Aust. Plan. 2020, 56, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, M.; Fogarty, J.; Zhang, F.; Pandit, R.; Pannell, D.J. The Value of Restoring Urban Drains to Living Streams. Water Resour. Econ. 2017, 17, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, M.; Farrelly, M.; Deletic, A.; Bach, P.M. Building Effective Planning Support Systems for Green Urban Water Infrastructure—Practitioners’ Perceptions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 89, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.H.F.; Brown, R.R. The Water Sensitive City: Principles for Practice. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Stewart, G.H.; Meurk, C. Planning and Design of Ecological Networks in Urban Areas. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, C.S.; Scott, D.; Baker, J.; Winemiller, K. Recreation and Amenity Values of Urban Stream Corridors: Implications for Green Infrastructure. J. Urban Des. 2013, 18, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Corporation. Drainage for Liveability Fact Sheet: Living Streams in Water Corporation Assets; Water Corporation, Department of Water: West Perth, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, S.; Polyakov, M.; Iftekhar, M.S. Capitalised Nonmarket Benefits of Multifunctional Water-Sensitive Urban Infrastructure: A Case of Living Streams. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2023, 67, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqueline, H.; Dickhaut, W.; Kronawitter, L.; Weber, B. Water Sensitive Urban Design: Principles and Inspiration for Sustainable Stormwater Management in the City of the Future; Jovis: Hamburg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.R.; Hobbs, R.J. Conservation Where People Live and Work. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The Role of Urban Parks for the Sustainable City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Associations between Park Characteristics and Perceived Restorativeness of Small Public Urban Green Spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.; van Dillen, S.M.E.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Streetscape Greenery and Health: Stress, Social Cohesion and Physical Activity as Mediators. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 94, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, J.; Wood, L.J.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B. Quality or Quantity? Exploring the Relationship between Public Open Space Attributes and Mental Health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordh, H.; Hartig, T.; Hagerhall, C.; Fry, G. Components of Small Urban Parks That Predict the Possibility for Restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Esnaola, M.; Forns, J.; Basagaña, X.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Rivas, I.; López-Vicente, M.; De Castro Pascual, M.; Su, J.; et al. Green Spaces and Cognitive Development in Primary Schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7937–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak, A. The Contribution of Local Parks to Neighbourhood Social Ties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.F.; Wilson, J.S.; Liu, G.C. Neighborhood Greenness and 2-Year Changes in Body Mass Index of Children and Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Greenspace and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e183–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Raymond, C.M.; Gulsrud, N.; Albert, C.; Coles, N.; Fagerholm, N.; Nagatsu, M.; Olafsson, A.S.; Soininen, N.; Vierikko, K. Radical Changes Are Needed for Transformations to a Good Anthropocene. npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, B.; Bolleter, J.; Barghchi, M.; Lund, J. Unpacking Park Cool Island Effects Using Remote-Sensed, Measured and Modelled Microclimatic Data. Land 2025, 14, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (Spatial) Planning Reexamined. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, M.; Reid, D.J.; Prodanovic, V. Are We Planning Blue-Green Infrastructure Opportunistically or Strategically? Insights from Sydney, Australia. Blue-Green Syst. 2021, 3, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Statistics for Australian Locations. Australian Government. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_003003_All.shtml (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- George, S. Sense of Place; The University of Western Australia Press: West Perth, Australia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Water Innovation Advisory Group. Water Innovation Advisory Group Report to Minister. Unpublished. Department of Water, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous government representative. Interview with Government Representative. edited by Julian Bolleter. Unpublished. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SurveyMonkey. Surveymonkey; SurveyMonkey: San Mateo, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Sajida, P.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Yigitcanlar, T. Developing Policy Scenarios for Sustainable Urban Growth Management: A Delphi Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, K.; Clark, B.; Brown, V.; Sitzia, J. Good Practice in the Conduct and Reporting of Survey Research. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2003, 15, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrydstrup, J.; Madsen, H.M.; Löwe, R.; Gregersen, I.B.; Pedersen, A.N.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K. Incorporating Objectives of Stakeholders in Strategic Planning of Urban Water Management. Urban Water J. 2020, 17, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, R.; Manuel, V.; Francisco, A.-B.; Gómez-Delgado, M. Green Infrastructure Design Using Gis and Spatial Analysis: A Proposal for the Henares Corridor (Madrid-Guadalajara, Spain). Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, B.; Hooper, P. Green Dreams: A Delphi Analysis of Suburban Forest Concepts; Australian Urban Design Research Centre: West Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena, A.; Iftekhar, S.; Fogarty, J. Quantifying Intangible Benefits of Water Sensitive Urban Systems and Practices: An Overview of Non-Market Valuation Studies. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2020, 24, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, C.J.; Klosterman, R.E.; Delaney, P.; Whitehead, A.L.; Kujala, H.; Bromage, A.; Nino-Ruiz, M. The Online What If? Planning Support System: A Land Suitability Application in Western Australia. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2015, 8, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Wang, Z.; Ma, H. Urban Construction Land Suitability Evaluation Based on Improved Multi-Criteria Evaluation Based on Gis (Mce-Gis): Case of New Hefei City, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Borthwick, A.G. Land-Use Suitability Analysis for Urban Development in Beijing. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Lu, M.; Lu, Y. Assessing the Suitability of Regional Human Settlements Environment from a Different Preferences Perspective: A Case Study of Zhejiang Province, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Shaikh, V.R. Site Suitability Analysis for Urban Development Using Gis Based Multicriteria Evaluation Technique. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2013, 41, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, S.; Habibi, K.; Koohsari, M.J. An Analysis of Urban Land Development Using Multi-Criteria Decision Model and Geographical Information System (a Case Study of Babolsar City). Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 5, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolleter, J.; Vokes, R.; Duckworth, A.; Oliver, G.; McBurney, T.; Hooper, P. Using Suitability Analysis, Informed by Co-Design, to Assess Contextually Appropriate Urban Growth Models in Gulu, Uganda. J. Urban Des. 2021, 27, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, M.; Martínez-Graña, A.; Santos-Francés, F.; Veleda, S.; Zazo, C. Multi-Criteria Analyses of Urban Planning for City Expansion: A Case Study of Zamora, Spain. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolleter, J. Background Noise: A Review of the Effects of Background Infill on Urban Liveability in Perth. Aust. Plan. 2016, 10, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, G. Urban Consolidation and the Inadequacy of Local Open Space Provision in Sydney. Urban Policy Res. 2011, 29, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.; Cozens, P. ‘Where Have All the Trees Gone?’ Urban Consolidation and the Demise of Urban Vegetation: A Case Study from Western Australia. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerald, M.; Stewart, I.D. The Urban Heat Island; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nardino, M.; Laruccia, N. Land Use Changes in a Peri-Urban Area and Consequences on the Urban Heat Island. Climate 2019, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. In OECD Green Growth Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Planning; Western Australian Planning Commission. Economic and Employment Lands Strategy: Non-Heavy Industrial Perth Metropolitan and Peel Regions; Western Australian Planning Commission: West Perth, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Planning Lands and Heritage. Urban Forest Mesh Blocks; Department of Planning Lands and Heritage: West Perth, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jisung, P. Slow Burn: The Hidden Costs of a Warming World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous civil engineer. Interview with Civil Engineer. edited by Julian Bolleter. Unpublished, 2016.

- Clim Systems. Simclim Ar6; Clim Systems: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2025; Available online: https://climsystems.com/simclim/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- IPCC. Ipcc Working Group 2 Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- David, H. Spaces of Global Capitalism; Verso: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, I.H. Ten Tenets and Six Questions for Landscape Urbanism. Landsc. Res. 2011, 37, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronwyn, F. ‘We Don’t Leave Our Identities at the City Limits’: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Living in Urban Localities. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 2013, 2013, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, C.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A. How Funding Scarcity and Ineffective Governance Tools Inhibit Urban Greenspace Provision: An Exploration of Municipal Greenspace Managers’ Insights. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 251, 105172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, S. Ecological Gentrification: A Research Agenda Exploring Justice in the City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth, G.A.; Lewis, T.L. The Environmental Injustice of Green Gentrification. In The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City; Lexington Books: Plymouth, UK, 2012; pp. 113–146. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Argelich, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.; Baró, F. Greening Plans as (Re)Presentation of the City: Toward an Inclusive and Gender-Sensitive Approach to Urban Greenspaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 127984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissa, C. Wiped out by the “Greenwave”: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability. City Soc. 2011, 23, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous hydrologist. Interview with Hydrologist. edited by Julian Bolleter. Unpublished. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, K. Thin Parks/Thick Edges: Towards a Linear Park Typology for (Post) Infrastructural Sites. J. Landsc. Archit. 2011, 6, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

| Subgroup | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Urban | Areas with higher urban density Regions that are zoned residential as opposed to other land uses Areas with limited Public Open Space availability |

| Societal | Areas that have populations engaging in low or no exercise Areas that have populations experiencing high levels of psychological distress Areas that have populations experiencing socio-economic disadvantage Areas with Aboriginal heritage |

| Environmental | Areas with threatened ecological communities Areas with high Land Surface Temperatures Areas with shallow depth of groundwater (e.g., where there tends to be surface water) Areas with water requiring nitrogen and phosphorus reduction Areas with low urban forest canopy cover |

| Occupation | Stage 1 Number | (%) | Stage 2 Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arboriculturist | 3 | (9%) | 3 | (10%) |

| Architect | 1 | (3%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Civil engineer | 1 | (3%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Environmental planner | 6 | (18%) | 3 | (10%) |

| Environmental scientist | 4 | (12%) | 3 | (10%) |

| Hydrologist | 4 | (12%) | 4 | (13%) |

| Landscape architect | 1 | (3%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Public health specialist | 1 | (3%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Sustainability officer | 2 | (6%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Urban designer | 4 | (12%) | 3 | (10%) |

| Urban ecologist | 2 | (6%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Urban planner | 1 | (3%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Unspecified | 3 | (9%) | 1 | (3%) |

| Total | 33 | (100%) | 23 | (74%) |

| Criterion | Criterion Group | Weighted Average (Stage 1) | Rank Order (Stage 1) | Rank Order (Stage 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areas with limited Public Open Space availability | Urban | 4.59 | 1 | 1 ► |

| Areas with low urban forest canopy cover | Environmental | 4.41 | 2 | 2 ► |

| Areas with higher urban density | Urban | 4.39 | 3 | 3 ► |

| Areas that have populations experiencing high levels of psychological distress | Societal | 4.27 | 4 | 7 ▼ |

| Areas with high Land Surface Temperatures | Environmental | 4.27 | 5 | 4 ▲ |

| Areas with threatened ecological communities | Environmental | 4.15 | 6 | 8 ▼ |

| Areas that have populations experiencing socio-economic disadvantage | Societal | 4.12 | 7 | 10 ▼ |

| Areas which have populations engaging in low or no exercise | Societal | 4.06 | 8 | 12 ▼ |

| Areas with water requiring nitrogen and phosphorous reduction | Environmental | 4.03 | 9 | 9 ► |

| Areas with shallow depth of groundwater | Environmental | 3.97 | 10 | 6 ▲ |

| Areas which are zoned residential | Urban | 3.72 | 11 | 11 ► |

| Areas with Aboriginal heritage | Societal | 3.7 | 12 | 5 ▲ |

| Criteria | Geospatial Layer | Classification | Preference Score | Criterion Weighting Based on Survey | Dataset Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban criteria | |||||

| Areas with limited Public Open Space availability | Park buffers (m) | 0–99 100–199 200–299 300–399 400–499 500–599 600–699 700–799 800–999 | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | 34 | Department of Planning Lands and Heritage |

| Areas with higher urban density | Residential lot size (m2) | 0–173 174–420 421–605 606–747 748–863 864–990 881–1232 1233–1624 1625–2000 | 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 | 14 | Landgate |

| Areas zoned residential | Land use | Industrial Urban (residential) Central city (mixed use) | 1 7 9 | 1 | Department of Planning, Lands, and Heritage |

| Environmental criteria | |||||

| Areas with threatened ecological communities | Threatened ecological communities | Vulnerable Endangered Critically endangered | 7 8 9 | 2 | Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions |

| Areas with low urban forest canopy cover | Urban forest canopy cover (%) | 0–5 5–10 10–15 15–20 20–25 25–30 30–35 35–40 40–100 | 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 | 22 | Department of Planning, Lands, and Heritage |

| Areas with shallow depth of groundwater | Minimum depth of groundwater (m) | 1–8 9–17 18–27 28–36 37–45 46–55 56–64 65–74 75–85 | 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 | 4 | Department of Water and Environmental Regulation |

| Areas with high Land Surface Temperatures | Land Surface Temperature °C | −8.8–28.1 28.2–29.4 29.5–31.4 31.5–34.3 34.4–37.1 37.2–39.9 40–42.7 42.8–45.8 45.9–56.6 | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | 11 | CSIRO |

| Areas with water requiring nitrogen and phosphorus reduction | Required phosphorus/ nitrogen reduction (%) | 0–9 10–44 45–100 | 1 5 9 | 2 | Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions |

| Societal criteria | |||||

| Areas that have populations engaging in low or no exercise | Low or no exercise per 100 people | 46–49 50–55 56–58 59–61 62–64 65–67 68–70 71–73 74–76 | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | 0 | PHIDU/Torrens University |

| Areas that have populations experiencing high levels of psychological distress | Psychological distress per 100 people | 8.1–9 9.1–10 10.1–11 11.1–12 12.1–14 14.1–15 15.1–16 16.1–17 17.1–20 | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | 3 | PHIDU/Torrens University |

| Areas with Aboriginal heritage | Aboriginal Heritage Places | Not a site Lodged Registered site | 1 7 9 | 6 | Department of Planning, Lands, and Heritage |

| Areas that have populations experiencing socio-economic disadvantage | Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas | 1–2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 | 1 | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bolleter, J. Towards Strategic Planning for Ephemeral Living Stream Drainage Upgrades. Land 2025, 14, 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122352

Bolleter J. Towards Strategic Planning for Ephemeral Living Stream Drainage Upgrades. Land. 2025; 14(12):2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122352

Chicago/Turabian StyleBolleter, Julian. 2025. "Towards Strategic Planning for Ephemeral Living Stream Drainage Upgrades" Land 14, no. 12: 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122352

APA StyleBolleter, J. (2025). Towards Strategic Planning for Ephemeral Living Stream Drainage Upgrades. Land, 14(12), 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122352