Planning Sustainable Green Blue Infrastructure in Colombo to Optimize Park Cool Island Intensity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

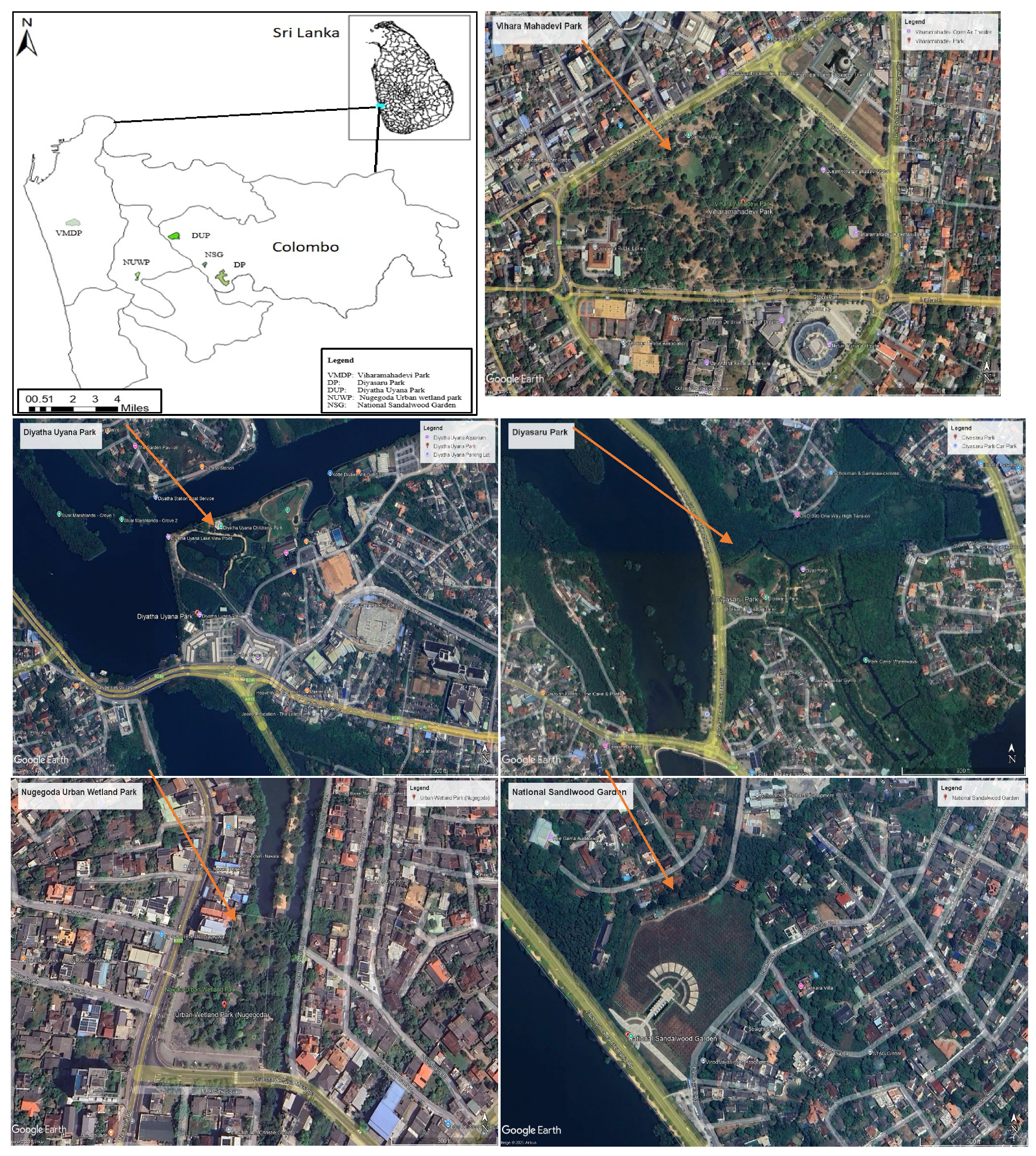

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Park Layout (Park Area, Park Perimeter, Park Shape)

2.1.2. Vegetation Structure in Urban Parks

2.1.3. Park Composition

2.1.4. Park Cool Island Intensity (PCII)

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Variation in PCII Across Each Park

4.2. Effect of Urban Park Size and PCII

4.3. Effect of Urban Park Vegetation Structure and PCII

4.4. Effect of Urban Park Composition and PCII

4.5. Other Factors Affecting PCII

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCI | Park Cool Island |

| PCII | Park Cool Island Intensity |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| UTM | Universal Traverso Mercator |

| CD | Canopy Density |

References

- Chapman, S.; Watson, J.E.M.; Salazar, A.; Thatcher, M.; McAlpine, C.A. The impact of urbanization and climate change on urban temperatures: A systematic review. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 1921–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M. Urban Heat Island: Causes, Effects and Mitigation Measures—A Review. Int. J. Environ. Monit. Anal. 2015, 67, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, J.L.; Hern, D.; Blanco, G.; Hiraldo, F. Urban Sprawl, Food Subsidies and Power Lines: An Ecological Trap for Large Frugivorous Bats in Sri Lanka? Diversity 2020, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleson, K.W.; Monaghan, A.; Wilhelmi, O.; Barlage, M.; Brunsell, N.; Feddema, J.; Hu, L.; Steinhoff, D.F. Interactions between urbanization, heat stress, and climate change. Clim. Change 2015, 129, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, V.; Marchadier, C.; Adolphe, L.; Aguejdad, R.; Avner, P.; Bonhomme, M.; Bretagne, G.; Briottet, X.; Bueno, B.; de Munck, C.; et al. Adapting cities to climate change: A systemic modelling approach. Urban Clim. 2014, 10, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, H.P.U.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Su, H.; Lin, H.; Lin, Y. Urbanization and its impacts on land surface temperature in Colombo Metropolitan Area, Sri Lanka, from 1988 to 2016. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, H.K.; Hamoodi, M.N.; Al-Hameedawi, A.N. Urban heat islands: A review of contributing factors, effects and data. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1129, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Nan, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Yan, H. Optimizing the Surrounding Building Configuration to Improve the Cooling Ability of Urban Parks on Surrounding Neighborhoods. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, M.F.J.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S.; Nilon, C.H.; Vargo, T. Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.P.I.K.; Halwatura, R.U.; Jayasinghe, G.Y. Evaluation of green infrastructure effects on tropical Sri Lankan urban context as an urban heat island adaptation strategy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, M.M.; Vardanyan, Z. The Benefits of Urban Parks, a Review of Urban Research. J. Nov. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Irfeey, A.M.M.; Chau, H.W.; Sumaiya, M.M.F.; Wai, C.Y.; Muttil, N.; Jamei, E. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies for Urban Heat Island Effects in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gou, Z.; Shutter, L. Effects of internal and external planning factors on park cooling intensity: Field measurement of urban parks in gold coast, Australia. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2019, 6, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, T.; Duque, J.A.G.; Dan, M.B. Urban planning with respect to environmental quality and human well-being. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 208, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Xi, J.; Yang, G.; Zhao, Y. Relationship between park composition, vegetation characteristics and cool island effect. Sustainability 2018, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; He, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Yu, X.; Shen, G.; Guo, R. Estimation of the relationship between urban park characteristics and park cool island intensity by remote sensing data and field measurement. Forests 2013, 4, 868–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.; Bell, S.; Toskovic, O.; Tomicevic, J.D.; Panagopoulos, T.; Straupe, I.; Kristianova, K.; Staigyte, L.; O’Brien, L.; Zivozjinovic, I. Tourist perceptions and uses of urban green infrastructure: An exploratory cross-cultural investigation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Nagendra, H. Perceptions of park visitors on access to urban parks and benefits of green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Jia, B. The roles of landscape both inside the park and the surroundings in park cooling effect. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, D.; Hou, Y.; Du, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G. Outdoor Thermal Comfort of Urban Park—A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.R.; Li, M.H.; Chang, S.D. A preliminary study on the local cool-island intensity of Taipei city parks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali Swain, R.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Chang, Y.; Bai, T.; Liu, P.; Song, H.; Wang, F.; Jin, M. Projections of Urban Heat Island Effects Under Future Climate Scenarios: A Case Study in Zhengzhou, China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngie, A. Thermal remote sensing of urban climates in south Africa through the mono-window algorithm. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLII-3/W11, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Emmanuel, R. The influence of urban design on outdoor thermal comfort in the hot, humid city of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2006, 51, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, V.R.F.; Damasceno, R.M.; Dias, M.A.; Castelhano, F.G.; Roig, H.L.; Requia, W.J. Ecosystem services provided by green areas and their implications for human health in Brazil. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Onishi, A.; Chen, J.; Imura, H. Quantifying the cool island intensity of urban parks using ASTER and IKONOS data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Pan, H.; Tian, L. Analysis of the spillover characteristics of cooling effect in an urban park: A case study in Zhengzhou city. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1133901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnfield, A.J. Two decades of urban climate research: A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. 2003, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yu, J.; Xin, C.; Ye, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Quantifying and Comparing the Cooling Effects of Three Different Morphologies of Urban Parks in Chengdu. Land 2023, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Yu, Y.; Liang, S.; Ren, Y.; Liu, M. Effects of urban green spaces landscape pattern on carbon sink among urban ecological function areas at the appropriate scale: A case study in Xi’an. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, M.; Reinhart, C.; Norford, L.; Ochsendorf, J. Urban heat island in boston—An evaluation of urban air temperature models for predicting building energy use. In Proceedings of the BS 2013: 13th Conference of the International Building Performance Simulation Association, Chambéry, France, 25–28 August 2013; pp. 1022–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S. The Impact of Urban Growth and Climate Change on Heat Stress in a Sub-Tropical Australian City. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi, M.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E. Design and Site-Related Factors Impacting the Cooling Performance of Urban Parks in Different Climate Zones: A Systematic Review. Land 2024, 13, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Kong, K.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Yin, L.; Zhang, B. Assessing the cooling effects of urban parks and their potential influencing factors: Perspectives on maximum impact and accumulation effects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendal, D.; Williams, N.S.G.; Williams, K.J.H. Drivers of diversity and tree cover in gardens, parks and streetscapes in an Australian city. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, N.; Vasiljevic, N.; Mešicek, M.; Lisica, A. The influence of roadside green spaces on thermal conditions in the urban environment. J. Archit. Plann. Res. 2018, 35, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Doyle, M.; McGovern, M.; Pasher, J. Air pollution removal by urban forests in Canada and its effect on air quality and human health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, A.P.; Andraz, J.; Ferreira, V.; Panagopoulos, T. Perceptions and preferences of urban residents for green infrastructure to help cities adapt to climate change threats. Cities 2023, 141, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makvandi, M.; Li, B.; Elsadek, M.; Khodabakhshi, Z.; Ahmadi, M. The interactive impact of building diversity on the thermal balance and micro-climate change under the influence of rapid urbanization. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, F.; Wang, B. Trends and variability of daily temperature extremes during 1960–2012 in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Glob. Planet. Change 2015, 124, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi Sigari, R.; Panagopoulos, T. A Multicriteria decision-making approach for urban water features: Ecological landscape architecture evaluation. Land 2024, 13, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Chen, M.; Jia, W.; Du, C.; Wang, Y. Cooling effect and cooling accessibility of urban parks during hot summers in China’s largest sustainability experiment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Guldmann, J.M.; Hu, L.; Cao, Q.; Gan, D.; Li, X. Linking urban park cool island effects to the landscape patterns inside and outside the park: A simultaneous equation modeling approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algretawee, H. The effect of graduated urban park size on park cooling island and distance relative to land surface temperature (LST). Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, A.P.; Andraz, J.; Ferreira, V.; Panagopoulos, T. Relevance of ecosystem services and disservices from green infrastructure perceived by the inhabitants of two Portuguese cities dealing with climate change: Implications for environmental and intersectional justice. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2025, 68, 1390–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Park | Area (ha) | Perimeter (m) | PCII (°C) | No. of Plots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUWP | 6.49 | 1617.11 | 0.82 ± 0.43 | 4 |

| DUP | 17.93 | 1866.86 | 1.02 ± 0.54 | 10 |

| VMDP | 23.16 | 1864.13 | 1.34 ± 0.21 | 15 |

| DP | 29.31 | 3738.92 | 1.46 ± 0.20 | 19 |

| NSG | 3.66 | 973.67 | 0.25 ± 0.49 | 2 |

| Park | PCII (°C) | Vegetation Characteristics | Park Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Density (n/ha) | Tree Height (m) | Tree Diameter (cm) | Basal Area (m2/ha) | CD (%) | Green Cover (%) | Water Cover (%) | Impervious Cover (%) | ||

| NUWP | 0.82 ± 0.43 | 62 | 16.67 | 40.08 | 5.96 | 68.4 | 73.8 | 18.5 | 7.7 |

| DUP | 1.02 ± 0.54 | 40 | 12.48 | 34.85 | 4.46 | 51.6 | 54.8 | 24.4 | 20.8 |

| VMDP | 1.34 ± 0.21 | 60 | 18.89 | 43.99 | 6.75 | 78.5 | 86.8 | 4.2 | 9 |

| DP | 1.46 ± 0.20 | 64 | 17.67 | 39.46 | 7.81 | 88.3 | 88.8 | 10.8 | 0.4 |

| NSG | 0.25 ± 0.49 | 9 | 5.21 | 15.87 | 1.21 | 10.2 | 78.5 | 5.6 | 15.9 |

| Category | Attribute | Regression Model | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Park Layout | Area (ha) | y = 0.0412x + 0.3138 | 0.877 |

| Perimeter (m) | y = 2.069ln(x) − 5.771 | 0.811 | |

| Shape (P/A) | y = −0.004673x + 1.751 | 0.701 | |

| Vegetation/Forest Structure | Stem Density (n/ha) | y = 0.01742x + 0.1594 | 0.717 |

| Tree Diameter (cm) | y = 0.03761x − 0.3328 | 0.757 | |

| Tree Height (m) | y = 0.07628x − 0.1038 | 0.784 | |

| Basal Area (m2/ha) | y = 0.1743x + 0.0649 | 0.868 | |

| Canopy Density (%) | y = 0.01459x + 0.1111 | 0.871 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wijesundara, A.A.S.G.; Sewwandi, B.G.N.; Panagopoulos, T. Planning Sustainable Green Blue Infrastructure in Colombo to Optimize Park Cool Island Intensity. Land 2025, 14, 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112164

Wijesundara AASG, Sewwandi BGN, Panagopoulos T. Planning Sustainable Green Blue Infrastructure in Colombo to Optimize Park Cool Island Intensity. Land. 2025; 14(11):2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112164

Chicago/Turabian StyleWijesundara, A. A. S. G., B. G. N. Sewwandi, and Thomas Panagopoulos. 2025. "Planning Sustainable Green Blue Infrastructure in Colombo to Optimize Park Cool Island Intensity" Land 14, no. 11: 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112164

APA StyleWijesundara, A. A. S. G., Sewwandi, B. G. N., & Panagopoulos, T. (2025). Planning Sustainable Green Blue Infrastructure in Colombo to Optimize Park Cool Island Intensity. Land, 14(11), 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112164