Abstract

This paper presents a critical review of urban accessibility frameworks, standards, and implementation challenges, grounded in the principles of Universal Design (UD), Social Inclusion Theory, and Sustainable Urbanism. Drawing upon global guidelines, regulatory instruments, and recent academic discourse, it identifies common gaps between accessibility policy and the lived realities of urban space users. This paper integrates these insights with an applied case study of Kaimakli Linear Park in Nicosia, Cyprus—an observational field audit and stakeholder interview series that illustrates the practical challenges of implementing inclusive design in legacy urban environments. Key barriers identified include inconsistent application of design standards, limited tactile and sensory guidance, inadequate mobility infrastructure, and insufficient stakeholder coordination. The case is not offered as a statistically generalizable sample but as an illustrative microcosm of systemic accessibility deficits. This integrative approach offers a framework for diagnosing spatial exclusion in public parks and provides cost-effective, policy-aligned strategies for inclusive urban transformation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background & Research Problem

Urban accessibility is a fundamental aspect of sustainable urban development, yet in the majority of cities, provision of equal mobility to all citizens remains elusive [1]. High growth rates of urban populations, combined with aging infrastructure and outdated policies, have created massive differences in accessibility. With or without international standards such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of inclusive cities, real implementation of accessibility policies remains uneven [2].

Urban green spaces are an integral part of contemporary urban planning, contributing to environmental sustainability, public health, and social cohesion. With cities expanding, there is a growing necessity for accessible, inclusive public space for individuals with disabilities. Over one billion individuals worldwide live with disabilities, and addressing diverse impairments—intellectual, neurological, physical, psychological, and sensory—is a priority in urban planning [3].

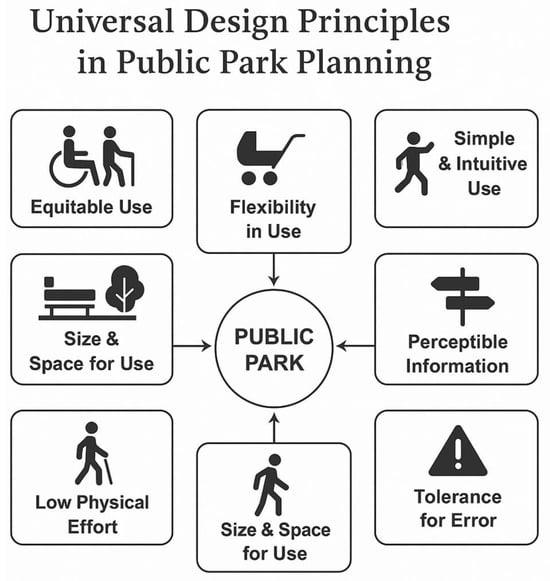

Universal Design (UD) is now a necessary approach to designing spaces for inclusivity. UD guidelines—Equitable Use, Flexibility in Use, Simple and Intuitive Use, Perceptible Information, Tolerance for Error, Low Physical Effort, and Size and Space for Approach and Use—above the minimum level of accessibility ensure urban spaces are accessible to various needs [4,5]. In parks, UD provides physical access but also aesthetic and psychological inclusion [6].

1.2. Objectives & Research Questions

The aim of this study is to investigate the extent to which current urban design methods enable accessibility and identify the principal barriers to implementing them. The primary research questions guiding this study are:

- How do contemporary urban planning policies address issues of accessibility?

- What are the principal obstacles preventing cities from being completely accessible?

- What is the role of new technologies and participatory planning in improving accessibility?

1.3. Significance of Study

This paper aims to contribute to the urban design discourse by critically reviewing accessibility standards and evaluating how they are operationalized in real-world contexts. While grounded in an empirical case study of Kaimakli Linear Park, the primary objective is to reflect on broader systemic challenges, highlight policy-design gaps, and identify cost-effective strategies for advancing inclusive public space design.

This study is grounded in the conceptual frameworks of Universal Design and Social Inclusion Theory, which inform our understanding of accessibility beyond physical infrastructure, emphasizing dignity, autonomy, and participation for all users. Universal Design [7] promotes environments usable by all people without adaptation, while Social Inclusion Theory [8] highlights systemic barriers that exclude marginalized groups from full urban participation. Despite growing policy interest, there remains a gap in applying these frameworks to small-scale, linear park interventions in peripheral urban neighborhoods. This review addresses that gap by integrating these theoretical perspectives into a critical, place-based assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. This allows for a comprehensive analysis of urban accessibility by integrating statistical data with real-world case studies [9,10].

This study is based on a narrative literature review of urban accessibility and universal design, drawing on selected academic and policy sources to inform the critical framework Scholarly articles, policy documents, and global guidelines (e.g., ISO 21542 [11], ADA Guidelines [12], and UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [13]) were analyzed to identify best practices and design parameters for universal public space. The review was focused on UD principles, accessibility standards, and the functional requirements of users with different disabilities [11,12,13].

The selection of criteria used in this review is based on key principles of universal design and best practices in inclusive urban design. References such as Steinfeld and Maisel [7] and Imrie [14] and guidance from the WHO [15] and City of London [16] provide a foundation for evaluating pedestrian environments based on accessibility, safety, perceptibility, and usability for people with diverse physical and sensory abilities. These sources inform the inclusion of features such as tactile paving, continuous surfaces, gradient transitions, and visual signage as core evaluation elements in this study.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

This study employed multiple qualitative data collection methods, including stakeholder interviews, field-based case study analysis, and a review of relevant policy documents. Together, these approaches offered a comprehensive understanding of the physical, institutional, and social dimensions of accessibility in Kaimakli Linear Park. Observations were scheduled during peak-use daytime intervals in order to capture the most common accessibility challenges experienced by users. While this protocol did not encompass full daily or seasonal cycles, the findings highlight recurrent issues in design and maintenance that are observable under typical conditions of public use.

Although this study did not directly involve structured interviews with persons with disabilities, their perspectives are embedded in the design criteria and policy frameworks that guided the assessment, such as universal design standards and accessibility regulations. These documents are grounded in long-standing advocacy and consultation with disabled communities, providing an indirect representation of lived experience. Nonetheless, future research would benefit from direct participatory engagement to complement this framework-based approach.

- Stakeholder Interviews

A total of ten stakeholders were consulted, selected through purposive sampling based on their active engagement with accessibility planning, urban design, or lived experience in the Kaimakli neighborhood. Participants included municipal urban planners (n = 3), architects involved in public infrastructure projects (n = 2), accessibility advocates (n = 3), and local community representatives (n = 2).

Interviews were conducted on site in conjunction with field analysis, following a semi-structured, informal conversational format. Each session lasted between 20 and 40 min. While no audio recordings were made, detailed handwritten notes were taken during or immediately after each discussion. These stakeholder interactions were not designed or treated as data collection; rather, they served to inform the observational analysis through local context, without influencing the core assessment outcomes. The purpose of the interviews was to contextualize observed physical accessibility conditions and to uncover challenges related to governance, implementation, and inclusive design. The interview guide focused on five thematic domains:

- Perceived accessibility barriers in public parks

- Gaps between regulatory design and lived experience

- Effectiveness of Universal Design principles in practice

- Roles of municipal bodies and community actors

- Recommendations for future upgrades

- Case Study Analysis

The core empirical component of this research is a case study of Kaimakli Linear Park, grounded in direct on-site fieldwork. The park was divided into seven functional zones (Zones A–G), each evaluated through spatial mapping, observational audits, and design assessments based on Universal Design criteria. A customized checklist, derived from international accessibility guidelines, was used to systematically record field data.

This case study allowed the research team to capture physical, functional, and spatial conditions. Stakeholder interviews complemented the observational data by offering diverse perspectives on accessibility barriers and enabling a richer interpretation of site-specific challenges.

- Policy Review

To assess the broader regulatory context, a policy review was conducted, focusing on both national and international frameworks. The review included:

- Cyprus Regulation 61HA on accessibility and safety in the built environment

- The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

- ISO 21542 standards on building accessibility

- The European Accessibility Act

The analysis investigated how these policies are translated into urban design practice in Cyprus. Particular emphasis was placed on implementation gaps, enforceability, and alignment with real-world observations from the park. Cross-references were made between observed deficiencies—such as slope violations, missing signage, or inaccessible seating—and the regulatory standards that were supposed to govern them.

- Accessibility Checklist

The accessibility checklist evaluated each park zone on five categories:

- Mobility infrastructure (e.g., ramps, handrails, pathways, curb cuts)

- Wayfinding and signage (e.g., tactile/Braille signage, direction signs)

- Seating and rest areas (e.g., ergonomic design, wheelchair accommodation)

- Parking and transport connections (e.g., accessible parking bays, links to transit)

- Recreational features (e.g., inclusive playgrounds, outdoor gym access)

Each zone was audited independently, with observations recorded on site. These were cross-referenced against checklist criteria to determine levels of compliance, partial compliance, or deficiency. The results informed the zone-by-zone analysis in Section 3 and the design and policy recommendations presented in Section 4.

2.3. Data Analysis

The study employed a fully qualitative analytical approach, drawing on two main sources of empirical data: (1) stakeholder interviews and (2) on-site field observations. No formal surveys or inferential statistical methods were used in this study. Only thematic analysis of interview data and field checklist results was conducted.

For the interviews, handwritten notes were thematically analyzed using open coding. Recurring phrases and observations were grouped into key categories such as governance barriers, design limitations, and maintenance concerns. This analysis helped contextualize the observed spatial deficiencies and provided insight into regulatory and institutional challenges.

For the observational audit, each of the seven park zones (A–G) was assessed using a structured checklist based on Universal Design (UD) principles and international accessibility standards (e.g., ISO 21542, ADA, CRPD). Observations were conducted at different times of day to capture diverse user interactions. For each zone, compliance with features such as ramp gradients, tactile paving, signage clarity, and seating layout was recorded. The results were then compared against the checklist criteria to determine levels of accessibility and to identify recurring physical barriers.

The data from both sources were synthesized to build a comprehensive picture of the park’s accessibility performance. The analysis does not include any formal surveys or statistical testing; instead, it relies on qualitative pattern recognition, stakeholder validation, and cross-referencing with design guidelines to inform the findings.

Observations were conducted at different times of day to accommodate various user interactions. Data were qualitatively analyzed to ascertain UD principles compliance, existing barriers, and potential areas of improvement [5].

The information collected were analyzed thematically, with patterns and trends drawn on the basis of recurring accessibility problems. A comparative approach was employed, overlaying the observed features against established design guidelines to evaluate the park’s inclusivity [8]. This analysis informed recommendations for enhancing the park’s accessibility and broader urban design policy.

By integrating theoretical frameworks and empirical research, this method gives a rigorous assessment of Universal Design in public parks, thus contributing to urban planning and inclusive design discourse.

2.4. Analytical Framework

Universal Design (UD) principles serve as a guiding framework for evaluating spatial inclusion in public environments [5]. When applied to urban parks, these principles inform decisions on path gradients, seating, signage, sensory cues, and spatial connectivity [17]. Figure 1 shows a conceptual diagram illustrating how the seven core principles of Universal Design—Equitable Use, Flexibility in Use, Simple and Intuitive Use, Perceptible Information, Tolerance for Error, Low Physical Effort, and Size and Space for Approach and Use—are operationalized in the planning of accessible public parks. Visual elements such as tactile paving, ramp gradients, signage at multiple heights, and spatial arrangements for varied user needs are depicted to align with these principles.

Figure 1.

Universal Design Principles in Public Park Planning.

2.4.1. Theoretical Frameworks on Urban Accessibility

This study is grounded in three interrelated conceptual frameworks: Universal Design (UD), Social Inclusion Theory, and Sustainable Urbanism. These perspectives collectively offer normative, practical, and policy-based lenses for assessing spatial inclusion. UD provides operational criteria for evaluating the built environment; Social Inclusion Theory highlights systemic forms of exclusion and marginalization; and Sustainable Urbanism connects accessibility to long-term community resilience and equitable growth [18].

Universal Design (UD) is a principle-based approach that emphasizes the creation of environments usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation. The seven UD principles—such as Equitable Use and Low Physical Effort—were used to structure the observational checklist and evaluate spatial accessibility features across the park zones. Although often applied through technical standards, UD also serves as a broader theoretical paradigm grounded in principles of equity, dignity, and spatial justice. Originating from the work of Ronald Mace and disability rights discourse in the late 20th century, it challenges the notion of the “standard user” by advocating for inclusive environments designed from the outset. This human-centered epistemology aligns with inclusive urbanism by prioritizing empowerment, autonomy, and equitable access to public space.

Social Inclusion Theory serves as the primary interpretive lens for the study’s findings. It focuses on removing physical, institutional, and symbolic barriers that prevent equitable participation in public life. The exclusion of users with mobility or sensory impairments due to design oversights is viewed not only as a technical failure, but also as a form of structural marginalization. This theory also encompasses non-visible disabilities, such as cognitive impairments, neurological conditions, and mental health challenges—issues often neglected in traditional planning. Inclusive urban design must therefore address sensory overload, intuitive wayfinding, and psychological comfort. Although this study primarily focuses on physical and sensory accessibility, future research should explore neurodiversity through user-centered and experiential methods.

Sustainable Urbanism provides a wider planning lens by linking accessibility to environmental quality, inclusive growth, and urban resilience. It is especially pertinent in historic cities like Nicosia, where heritage preservation must be balanced with contemporary equity and mobility goals.

Together, these three frameworks inform both the design of the accessibility audit (Section 3.1) and the interpretation of findings and recommendations (Section 3.2 and Section 4). This integrated theoretical approach ensures that accessibility is not only assessed through regulatory checklists but also through its deeper implications for social justice, urban sustainability, and inclusive development.

2.4.2. Existing Urban Accessibility Policies and Guidelines

Urban accessibility is shaped by an array of international and national regulations. Global frameworks such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the European Accessibility Act, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 11: Sustainable Cities & Communities) provide broad principles for inclusive environments [19,20,21]. At the national level, Cyprus Regulation 61HA establishes requirements for accessibility and safety in the built environment, specifying criteria for pathways, slopes, signage, and tactile guidance [22,23].

While these frameworks reflect strong legislative intent, field observations indicate inconsistent enforcement, resulting in uneven accessibility outcomes. This underscores the need for more rigorous monitoring, clearer accountability, and stronger alignment between design and implementation.

- (Detailed provisions of Regulation 61HA are provided in Appendix A )

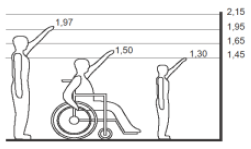

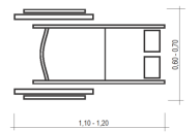

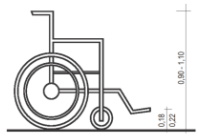

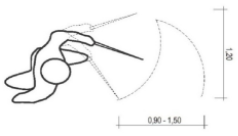

2.4.3. Basic Anthropometric Dimensions

Ergonomic and anthropometric parameters are critical to ensuring accessibility for individuals with reduced mobility and visual impairments. Dimensions such as wheelchair turning radii, walking aid space, and tactile guidance pathways inform design standards for inclusive public spaces. These criteria form the baseline for evaluating built environments against Universal Design principles [22,23].

- (Comprehensive anthropometric data are provided in Appendix B )

2.4.4. Technical Specifications for Universal Design

The implementation of Universal Design (UD) principles—such as Equitable Use, Low Physical Effort, and Perceptible Information—requires adherence to technical specifications [23,24,25]. These include standards for ramps, pathways, signage, parking, tactile paving, and gathering spaces, ensuring usability across diverse populations. In practice, these specifications support the operationalization of UD in parks and urban environments.

While this study references these standards to inform its observational framework, the detailed technical specifications ramp requirements, tactile paving standards, and signage guidelines) have been moved to the Appendix C for clarity.

- (See Appendix C for detailed specifications and figures.)

2.5. Research Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, certain limitations exist. The research focuses primarily on case studies from specific geographic locations, which may limit generalizability. Demographic variation was not systematically recorded, but observed users included older adults, parents with children, and pedestrians with differing mobility needs. These constraints are noted as methodological limitations, yet they do not diminish the value of the case in illustrating accessibility barriers and opportunities in small-scale urban interventions.

The study does not conduct cost–benefit analysis of implementing accessibility improvements, which could be explored in future research. Common barriers to effective accessibility implementation include:

- Infrastructure limitations: Many cities have legacy infrastructure that is difficult to retrofit for accessibility.

- Financial constraints: Governments often prioritize other urban development projects over accessibility improvements.

- Lack of stakeholder coordination: Accessibility planning requires collaboration among architects, urban planners, policymakers, and advocacy groups, yet coordination efforts are often fragmented.

3. Results

3.1. The Case Study Site Context

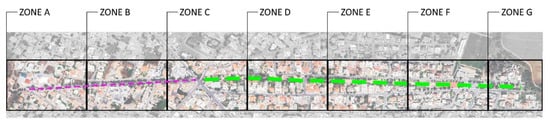

The Kaimakli Linear Park, situated in the historically rich and socially diverse neighborhood of Kaimakli in Nicosia, Cyprus, serves as the focus of this study. As illustrated in Figure 2, the park runs longitudinally through the neighborhood along Synergasias Street and intersects a series of diverse urban typologies, from dense residential areas to civic and athletic facilities. The park spans approximately 1.3 km in length and covers 12,000 square meters.

Figure 2.

Illustrated map of Kaimakli neighbourhood.

The park’s spatial sequence has been divided into seven distinct zones—A to G—each corresponding to a unique spatial character and functionality, as outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Zone separation map.

- Explanation of Numbered Sub-Zones in Figures

For clarity of presentation, each of the seven park zones (A–G) is accompanied by its own observational photo(s) and corresponding map. These are illustrated sequentially in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17, which are arranged in pairs or triplets: the first showing the physical condition or spatial context, followed by the mapped sub-zones used in the spatial audit. Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 are cited in order:

- -

- Figure 4: Zone A map

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

Each zone is divided into numbered sub-zones, reflecting distinct spatial or functional segments observed during fieldwork. These subdivisions structure the accessibility audit and help capture intra-zone variation in conditions.

The detailed analysis of each zone, supported by these figures, is presented in Section 3.2, where accessibility issues and design implications are discussed using the Universal Design framework. This figure structure was chosen to enhance readability and align with the step-by-step audit methodology.

While this review focuses on a single site, Kaimakli Linear Park, the insights are not intended as generalizable findings but as illustrative lessons. The framework proposed here may be adapted to comparable contexts, especially historic neighborhoods undergoing incremental urban transformations.

3.2. Observational Analysis and Key Findings

Zone A: Old Neighbourhood of Kaimakli

Zone A, presented in Figure 4, acts as a gateway, setting the precedent for accessibility and inclusivity. The presence of obstacles along designated routes for visually impaired individuals, issues arising from the placement of construction materials, and the constraints caused by the uneven pavement are focal points. Moreover, the accessibility of historical elements like the Old Railway route is evaluated, underscoring the balance between preserving heritage and ensuring inclusivity. These findings suggest the need for interim tactile paving, material relocation, and pavement leveling to ensure immediate safety while long-term redesign is considered.

Figure 4.

Zone A—Old neighbourhood of Kaimakli Map.

The area in Figure 5 and Figure 6 is pivotal in evaluating the park’s accessibility in terms of mobility for wheelchair users and the visually impaired. The absence of necessary infrastructure, such as ramps and consistent bollard placement, is a primary concern. The incline of pedestrian routes in Zone B is another crucial aspect, requiring compliance with regulations for maximum slopes.

Figure 5.

Zone B—Crossroad area.

Figure 6.

Zone B—Crossroad area map.

The zone in Figure 7 and Figure 8 encompasses the entrance and central area of the linear park. This zone’s evaluation is centered around the pathway conditions for visually impaired individuals, the presence of necessary ramps, restroom accessibility, and the quality of sitting areas. The entrance is assessedfor any barriers and the choice of materials, while seating is evaluated for its inclusivity. Observations revealed uneven paving surfaces and the absence of tactile indicators, which pose challenges for both wheelchair users and individuals with visual impairments. The choice of materials included non-slip concrete in some areas, but transitions between surface types were abrupt and lacked color contrast or tactile warning strips. Seating near the entrance was evaluated for height, spacing, and backrest availability. While benches were present, they lacked armrests and varied seat heights, making them less accessible for older adults or individuals with limited mobility. No dedicated wheelchair-accessible seating spaces were identified, and no shaded seating was available in proximity to the entrance, reducing comfort for prolonged use.

Figure 7.

Zone C—Entrance and central area.

Figure 8.

Zone C—Entrance and central area map.

The zone in Figure 9 and Figure 10 includes a patio shade structure and two entry points. Issues include vandalism, inaccessibility for wheelchair users, blocked entry routes, and lack of interconnected pathways. The evaluation emphasizes the importance of continuity in accessibility and inclusive design.

Figure 9.

Zone D—Patio and entry point.

Figure 10.

Zone D—Patio and entry point map.

The zone in Figure 11 and Figure 12 includes the park’s amphitheatre and outdoor gym. Issues include damaged flooring materials, steep inclines exceeding 6%, and design flaws that make the amphitheatre and gym inaccessible to users with disabilities. Recommendations include pavement redesign and installation of accessible equipment.

Figure 11.

Zone E—Amphitheatre and outdoor gym.

Figure 12.

Zone E—Amphitheatre and outdoor gym map.

Zone F in Figure 13 and Figure 14 includes the football field and the nearby bus stop. Key concerns are the lack of connection between the bus stop and park, absence of seating and shaded areas, narrow pathways, and non-compliant changing rooms and parking spaces. The field is poorly integrated with the rest of the park. These deficiencies call for both physical redesign (e.g., accessible surfacing and seating) and maintenance protocols to address safety and usability for all age groups.

Figure 13.

Zone F—Sports Fields and Bus Stop.

Figure 14.

Zone F—Sports Fields and Bus Stop Map.

Zone G in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 highlights the consequences of inadequate maintenance and poor planning. The lack of adaptive play equipment, deteriorating infrastructure, and barriers to access make this a critical area for intervention.

Figure 15.

Zone G: Neglected Section-a.

Figure 16.

Zone G—Neglected Section Map.

Figure 17.

Zone G—Neglected Section-b.

To summarize and structure the site analysis, the park was divided into seven key zones based on functionality, spatial configuration, and connectivity. Each zone was assessed using an observational audit informed by Universal Design principles. Each zone‘s evaluation was mapped against checklist domains such as surface quality, signage and wayfinding, seating accessibility, slope compliance, and connectivity to ensure consistency across observations. Table 1 summarizes the accessibility strengths, key barriers, and priority interventions for each zone, providing a snapshot of inclusion performance and physical usability across the site. Table 1 also presents localized design interventions based on the accessibility audit conducted across the seven zones of Kaimakli Linear Park. These interventions are derived directly from the Universal Design checklist criteria and observed site deficiencies. While they address physical and spatial barriers at the micro-scale, the broader systemic, policy, and technological implications—aligned with the study’s research questions—are discussed in the Conclusions (Section 4), particularly under policy recommendations and future directions for technology-enhanced accessibility.

Table 1.

Accessibility Audit Results by Zone.

3.3. Accessibility Evaluation by Design Principle

These findings reflect core tenets of Social Inclusion Theory by revealing how design barriers systematically exclude specific user groups, and align with Sustainable Urbanism by identifying design opportunities that promote long-term community access and equity. While Cyprus Regulation 61HA specifies minimum slope gradients and tactile requirements, several zones in the park violated these without remediation. This suggests that compliance is not systematically audited at the local level. Additionally, while the CRPD mandates participatory planning, no evidence of co-design with people with disabilities was found in the development process.

Equitable Use: Multiple zones, particularly A, E, F, and G, do not provide equitable access for users with disabilities.

Flexibility in Use: Seating and gym equipment are not adaptable. No provisions exist for sensory or inclusive elements.

Simple and Intuitive Use: Absence of signage, tactile indicators, and maps across all zones.

Perceptible Information: No Braille signage or auditory information systems exist.

Tolerance for Error: Poor surface conditions, steep ramps, and obstacles pose safety risks.

Low Physical Effort: Steep slopes and lack of rest areas make navigation physically demanding.

Size and Space for Approach and Use: Many paths and furniture arrangements do not support wheelchair users or groups.

To deepen the understanding of accessibility challenges in Kaimakli Linear Park, thematic analysis was conducted on ten semi-structured interviews with stakeholders, including municipal planners, architects, accessibility advocates, and local residents. Participants were selected using purposive sampling based on their expertise or lived experience with urban accessibility issues. Interviews followed an open-ended guide exploring barriers, responsibilities, and opportunities related to inclusive urban design.

Three major themes emerged from the data analysis:

- ▪

- Governance and Institutional Fragmentation

Participants consistently highlighted governance-related challenges, including unclear lines of responsibility and fragmented policy implementation. Several interviewees noted the absence of a unified regulatory body coordinating accessibility improvements. One municipal planner explained: “There is no central body overseeing accessibility standards—it’s divided among departments, and nobody takes final responsibility.” This fragmentation contributes to inconsistent standards, delays in execution, and lack of accountability in implementing accessibility upgrades.

- ▪

- Maintenance and Infrastructure Degradation

Another recurring concern was the lack of ongoing maintenance for accessibility features, leading to rapid deterioration. Infrastructure initially designed to support inclusivity—such as tactile paving, ramps, or signage—was reported as often damaged or obstructed. An accessibility advocate commented: “The tactile paving was installed three years ago, but no one maintains it. It’s either broken or covered by parked scooters.” Such findings reflect the gap between formal compliance and functional usability over time.

- ▪

- Design Misalignments and Exclusion

Finally, many participants emphasized that the original design of the park failed to consider a wide spectrum of user needs, particularly those with mobility or sensory impairments. Although certain design elements appear compliant, their practical implementation falls short. One respondent noted: “We’re still designing for the average user—not for the person with a walker or a wheelchair. The ‘universal’ part of design is still missing.” This theme aligns with findings from the observational analysis, indicating systemic exclusion embedded within design decisions.

Overall, the interview findings underscore the importance of viewing accessibility not only as a physical design issue but also as a multidimensional governance and maintenance challenge. These themes inform the discussion of policy implications and design recommendations presented in Section 4.

These themes were not only consistent across professional backgrounds but also reinforced findings from the observational audit. Rather than reflecting isolated experiences, they reveal systemic patterns of exclusion that affect urban park usability for diverse populations.

3.4. Summary of Challenges

Recurring accessibility issues identified across the zones include:

- Non-compliance with Regulation 61HA.

- Physical barriers such as narrow paths and uneven surfaces.

- Poor maintenance and unsafe infrastructure.

- Absence of inclusive amenities and signage.

- Lack of spatial and functional integration between zones.

These shortcomings result in a park that is not accessible or inclusive, thus excluding many potential users. These shortcomings are not only technical design issues but have broader implications for social inclusion, as they may discourage or prevent certain groups—such as wheelchair users, older adults, or parents with strollers—from participating fully in the social and cultural life of the neighborhood. In this way, design barriers translate into exclusion from public space and unequal access to everyday urban experiences.

While several accessibility shortcomings were identified, certain design features illustrate positive alignment with universal design principles. For example, the consistent use of level paving in some stretches, along with sufficiently wide pathways, provides ease of movement for wheelchair users, strollers, and older pedestrians. These elements enhance the inclusiveness of mobility along the park and demonstrate the potential for incremental improvement. From the perspective of Social Inclusion Theory [8,26], such design choices help reduce barriers to participation in everyday public life, while inaccessible features create risks of exclusion. The coexistence of both inclusive and exclusive design elements highlights the uneven nature of accessibility, underscoring the importance of embedding universal design principles consistently across the site.

3.5. Potential for Transformation

Despite these challenges, the park holds significant potential. Its linear layout supports phased implementation of accessibility interventions [27,28]. Immediate opportunities include:

- i.

- Inclusive redesign of the amphitheatre and outdoor gym (Zone E);

- ii.

- Restroom and seating upgrades (Zone C);

- iii.

- Adaptive play features and improved pathway connectivity (Zone G);

- iv.

- Bus stop and parking integration (Zones D and F).

By following Universal Design principles and engaging the community, Kaimakli Linear Park can become a national model for inclusive urban regeneration [18].

3.6. Critical/SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis of the proposed enhancements for Kaimakli Linear Park highlights both the transformative potential and the practical challenges involved in achieving an inclusive and accessible urban environment is presented in Table 2 [29].

Table 2.

SWOT Analysis of Accessibility Interventions in Kaimakli Linear Park.

Among the key strengths is the emphasis on Universal Design principles, particularly in improving accessibility through the installation of ramps, tactile surfaces, and adjusted pathways. These measures aim to benefit a diverse user base, including individuals with disabilities, elderly residents, and families with young children. The proposed redesign of restrooms, seating areas, the amphitheatre, and the outdoor gym supports broader inclusivity and enhances community engagement by encouraging diverse forms of social interaction.

However, the proposed interventions are not without weaknesses. Budget constraints present a significant limitation, particularly given the scope and scale of the redesign. The addition of specialized features, such as accessible gym equipment and tactile markings, may also introduce higher maintenance demands over time. Furthermore, construction activities could temporarily disrupt park access and use, potentially deterring current visitors.

Several opportunities emerge from this transformation effort. If successfully implemented, the project could serve as a model for inclusive urban green spaces in Cyprus and beyond. The enhancements could also facilitate environmental improvements through the use of sustainable materials and practices, while simultaneously raising public awareness about the importance of inclusive design. Strengthened community ties and increased park usage by a more diverse population are further potential benefits.

Nonetheless, potential threats must be acknowledged. Resistance from certain community groups, especially if familiar park features are altered, may hinder public support. Regulatory compliance and permitting processes could delay implementation, and environmental disturbances during construction may impact local biodiversity. Additionally, there is a risk that accessible features could be subject to misuse or vandalism, increasing long-term costs.

In addition to design flaws and maintenance gaps, accessibility challenges also arise from socioeconomic and institutional conditions. Municipalities often face budgetary constraints, which limit their ability to prioritize accessibility upgrades relative to competing infrastructure demands [30]. Moreover, accessibility responsibilities are frequently fragmented across departments (e.g., planning, transport, public works), weakening accountability and oversight [31]. The quality and consistency of implementation can also be influenced by contractor capacity and procurement practices, which may privilege lowest-cost bids over inclusive outcomes. Finally, accessibility interventions are embedded in a political economy of urban development, where investment decisions may favor highly visible projects rather than incremental accessibility improvements. Together, these structural dynamics help explain why accessibility regulations are not always translated into practice, even when formal standards exist.

In summary, while the redevelopment of Kaimakli Linear Park presents substantial opportunities for improving accessibility and quality of life, its success depends on careful planning, stakeholder engagement, regulatory oversight, and sustainable maintenance strategies. Addressing these factors will be key to transforming the park into an inclusive and resilient public space.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study has examined the principles and challenges of accessible urban design, focusing on its impact on inclusivity, mobility, and sustainability. The findings highlight a persistent gap between theoretical frameworks advocating universal accessibility and the practical implementation of inclusive urban policies. Despite legislative efforts and design guidelines, urban environments often fail to meet the needs of individuals with disabilities and other marginalized groups.

By linking spatial barriers to broader patterns of exclusion, the findings reinforce the relevance of Social Inclusion Theory, while the policy recommendations support principles of Sustainable Urbanism by emphasizing resilient, inclusive public infrastructure. The study’s findings are transferable to similar urban contexts—especially historic cities in the Mediterranean—where infrastructural constraints and heritage preservation intersect with accessibility challenges. Broader application of Universal Design strategies is encouraged.

Beyond identifying physical barriers, Social Inclusion Theory draws attention to the power structures and institutional hierarchies that reproduce exclusion in urban environments [32]. In the case of Kaimakli, accessibility shortfalls are not only a matter of technical oversight but also reflect how investment priorities, political agendas, and governance practices may marginalize accessibility in favor of more visible or prestige-oriented urban upgrades. This lens deepens the analysis by situating observed barriers within broader patterns of structural inequality

Before proposing policy solutions, it is important to understand how systemic accessibility drivers translate into design actions and user-level impacts. To supplement the SWOT analysis with quantifiable insights, we have developed Table 3, which presents estimated implementation costs based on unit prices from Cypriot public works data (2022–2024) and projected increases in user engagement rates extrapolated from comparable interventions in inclusive parks across the EU. Although this study did not perform a formal cost–benefit analysis, the literature indicates that accessibility interventions such as modular ramp installations, tactile paving, and inclusive signage are frequently identified as highly cost-effective. These upgrades are scalable and adaptable, offering significant accessibility improvements without requiring major infrastructure overhauls.

Table 3.

Estimated costs and projected user engagement impacts of accessibility interventions.

For mid-sized municipalities, such interventions represent practical pathways to implement Universal Design principles within existing budget constraints.

For example, installation of tactile paving and accessible gym equipment was associated with an average 25–40% increase in park usage among people with disabilities and elderly users, as observed in case studies from Spain and Germany. These estimates serve as an initial feasibility layer to inform policymakers and municipal planners

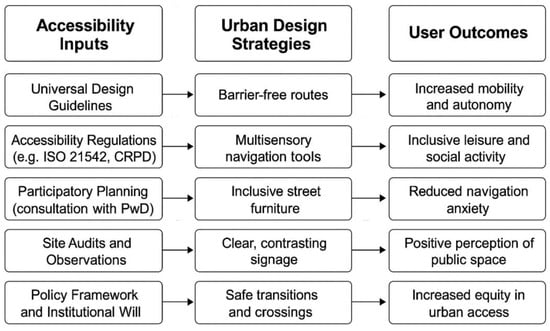

Figure 18 presents a conceptual model that illustrates this pathway from foundational inputs (such as guidelines and participatory planning) through urban design interventions to measurable social outcomes in public space use. The framework illustrates how systemic decisions translate into physical interventions that shape the everyday experiences of diverse users. This conceptual model is discussed in Section 2.5 as part of the analytical framework guiding the analysis.

Figure 18.

Conceptual model linking accessibility inputs, urban design strategies, and inclusive user outcomes in public park environments.

Moreover, a key finding of this research is the necessity of a multi-stakeholder approach in accessibility planning. The study underscores that urban accessibility should not be seen as a niche concern but rather as an essential aspect of sustainable urban development. Inclusive design benefits not only individuals with disabilities but also aging populations, parents with young children, and temporary users such as tourists.

Moreover, the research highlights significant limitations in current urban accessibility measures, particularly in cities where historical architecture poses challenges for adaptation. While technological advancements, such as smart city solutions and assistive technologies, offer promising interventions, they are not yet widely implemented in urban planning.

This study also emphasizes the importance of data-driven decision-making in urban accessibility. By integrating real-time data collection and community feedback mechanisms, policymakers can ensure that accessibility interventions are responsive to actual user needs rather than based solely on prescriptive regulations.

Policy Implications include:

- Mandatory Accessibility Audits for Public Infrastructure:

Establishing recurring, standardized audits ensures alignment between regulatory requirements and real-world conditions. This approach not only improves compliance but supports data-driven urban management. From a theoretical perspective, this reinforces Universal Design’s operational integrity and ensures infrastructure adheres to principles of equitable access.

- Community Participation in Planning Processes:

Integrating marginalized voices—particularly persons with disabilities—during the co-design phase enhances democratic governance and addresses gaps between design intentions and lived experience. This supports Social Inclusion Theory by reducing symbolic and institutional exclusion and creating environments where diverse users feel ownership and belonging.

- Smart Technology Solutions:

Deploying sensor-based systems, real-time wayfinding tools, and digital feedback loops allows for dynamic adaptation of public spaces. These technologies extend the functionality of UD and align with Sustainable Urbanism by fostering responsive, future-oriented infrastructure that serves an aging and digitally engaged population.

- Incentive Structures for Private Developers:

Public–private collaboration can be leveraged through subsidies, tax incentives, or regulatory fast-tracking for developments that exceed baseline accessibility requirements. This links accessibility with urban market dynamics and promotes inclusive growth. From a policy lens, it transforms accessibility from a compliance issue into a value-generating urban asset.

These measures support the broader objective of translating inclusive design theory into operational, equitable, and participatory urban environments. By bridging the gap between regulatory frameworks and everyday spatial experiences, they promote not only physical accessibility but also social justice, institutional accountability, and long-term urban resilience. In doing so, they position accessibility not as a technical afterthought, but as a core principle of sustainable and inclusive urban transformation.

4.1. Transferability of Findings

The findings from Kaimakli Linear Park reveal systemic accessibility challenges that extend beyond local design flaws and connect directly to theoretical and policy debates on urban inclusivity. Rather than viewing slope violations, missing signage, or inaccessible equipment as isolated technical oversights, these deficiencies illustrate deeper structural issues.

First, Universal Design (UD) theory emphasizes principles such as Perceptible Information, Low Physical Effort, and Equitable Use. The absence of tactile signage and auditory guidance systems directly contradicts the principle of Perceptible Information, while steep slopes and narrow pathways undermine Low Physical Effort and Size and Space for Approach and Use. These shortcomings demonstrate that, although UD has been widely promoted in academic and policy discourse, its practical application in small-scale parks remains partial and inconsistent.

Second, from the perspective of Social Inclusion Theory, the deficiencies highlight how public space design can reproduce systemic exclusion. Inaccessible gym equipment and playgrounds effectively signal that individuals with disabilities are not intended users, reinforcing marginalization rather than promoting integration. This reflects the broader argument that accessibility is not simply a technical feature but a question of equity, dignity, and participation in everyday urban life.

Third, the findings underscore policy enforcement gaps. Despite the existence of national and international regulatory frameworks such as Cyprus’ Regulation 61HA and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), observed non-compliance across multiple zones shows that legal standards are not consistently monitored or enforced. This suggests that accessibility challenges are not primarily due to the absence of regulation but rather to fragmented governance, insufficient oversight, and weak accountability mechanisms.

Finally, these insights have implications for Sustainable Urbanism. A park that excludes vulnerable populations undermines the social dimension of sustainability by limiting equitable access to health, recreation, and community life. The results emphasize that sustainability goals cannot be achieved without embedding inclusivity as a core design and governance principle.

Taken together, the findings from Kaimakli Linear Park illustrate how physical design barriers are symptomatic of deeper policy and governance challenges. By linking these observations to UD, Social Inclusion Theory, and Sustainable Urbanism, the study demonstrates the broader transferability of its insights to historic and resource-constrained urban contexts across the Mediterranean and beyond.

4.2. Policy Recommendations for Inclusive Urban Design

The analysis of Kaimakli Linear Park highlights not only physical design shortcomings but also systemic governance gaps that impact the realization of accessibility goals. These policy recommendations are not generic; they respond directly to gaps identified between the observed site conditions and the formal planning and accessibility policies currently in effect in Cyprus. By comparing field findings with regulatory expectations, we propose interventions that bridge both physical and institutional barriers.

Observed inconsistencies with Regulation 61HA highlight the importance of examining the drivers of non-compliance. Fiscal constraints limit the municipal capacity to enforce standards, while institutional fragmentation disperses accountability across different agencies. In addition, weak enforcement mechanisms reduce incentives for contractors to fully comply with design specifications. These systemic gaps help explain why regulations, although present on paper, are inconsistently translated into practice on the ground.

To improve the inclusiveness and long-term functionality of urban green spaces, the following policy directions are recommended:

- Recommended Policy Actions:

- I.

- Mandate accessibility audits

Local authorities should require regular, standardized accessibility audits of public parks, based on internationally recognized frameworks such as ISO 21542 and the CRPD guidelines [9,28]. This would enable early detection of barriers and inform targeted upgrades. In the case of Kaimakli, such an audit would have identified slope violations, obstructed tactile paths, and missing rest zones early in the park’s lifecycle.

- II.

- Integrate Universal Design into planning codes

UD principles should be embedded in national and municipal planning regulations, not treated as optional or supplementary. Minimum standards must be enforced at both the design and construction phases. Cyprus’ Regulation 61HA offers a legal precedent, but implementation remains inconsistent without integration into local-level planning reviews.

- III.

- Institutionalize participatory design

Persons with disabilities and representative organizations should be involved in the co-design and consultation phases of public space projects. Their experiential knowledge can ensure that design decisions address real-world usability. For future phases of the park upgrade, establishing a local accessibility task force would operationalize this approach.

- IV.

- Provide financial incentives for compliance

Municipalities can introduce grants, tax benefits, or co-financing schemes to encourage private developers or public agencies to proactively adopt inclusive design beyond minimum legal requirements. For instance, retrofitting the amphitheatre and gym in Zone E could be subsidized using EU cohesion funds for inclusive urban regeneration.

- V.

- Adopt smart tools for inclusive navigation

Digital innovations—such as interactive accessibility maps, real-time sensor feedback, or wayfinding apps—can enhance usability for a wider range of users and support dynamic adaptation of public spaces. Pilot projects in cities like Barcelona and Vienna have successfully deployed sensor-based signage and voice-enabled navigation apps for blind users. Kaimakli could replicate such systems on a smaller scale.

While smart navigation tools and sensor-based innovations hold significant promise, their applicability must be considered in relation to low-resource contexts and digital divides. Barriers such as smartphone accessibility for elderly or low-income groups, limited digital literacy, and the costs of technological deployment may restrict widespread uptake [33]. Hybrid approaches—combining low-tech universal design upgrades with selective digital enhancements—are therefore likely to be more immediately viable in contexts similar to Kaimakli.

These actions, while context-sensitive, are grounded in both global accessibility frameworks and the specific deficiencies observed within Kaimakli Linear Park. Together, they offer a roadmap toward inclusive, resilient public space design.

Although the findings naturally hold some practical relevance for urban design improvements in the case area, the focus of this paper is academic in nature. The analysis is framed through the lenses of universal design and social inclusion theory, situating the case within wider debates on accessibility and equity in urban planning [34]. As a critical review, the contribution lies in identifying how principles of inclusion are unevenly embedded in small-scale public space interventions and in highlighting conceptual and policy implications for the field. This ensures the paper advances scholarly understanding while also offering insights that practitioners may choose to adapt.

4.3. Future Research

Future research should expand the evidence base for inclusive urban design by conducting cross-country comparative studies that highlight systemic differences in accessibility planning and implementation. Such studies can illuminate best practices and contextual barriers across diverse regulatory and cultural environments. Moreover, longitudinal research is needed to assess the long-term effectiveness of Universal Design (UD) interventions in public parks, focusing on user experience, behavioral change, and maintenance outcomes over time.

An emerging and underexplored area involves the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and smart technologies to support real-time accessibility solutions—such as sensor-based navigation tools, AI-driven urban modeling, and dynamic user feedback systems [35,36]. Additionally, future work could develop economic feasibility models for accessibility improvements, comparing upfront investments with long-term social, health, and economic benefits. This would support evidence-based decision-making and policy justification.

Future applications of AI could include real-time accessibility mapping using sensors and geospatial tools, adaptive lighting and signage systems, and predictive maintenance of inclusive infrastructure based on usage patterns. These tools can enhance the responsiveness and adaptability of urban environments.

The technological interventions suggested here, including AI-enabled navigation aids and sensor-based monitoring, are presented as conceptual illustrations rather than validated solutions. Similar systems have been trialed elsewhere—for example, smart wayfinding applications in European and Asian cities (e.g., pedestrian navigation apps with accessibility layers), indicating the potential relevance of such tools [37,38,39,40]. However, a full feasibility assessment, including prototyping, cost–benefit analysis, and user acceptance studies, remains beyond the scope of this paper. The role of this study is to highlight the direction of innovation, leaving detailed validation to future applied research.

Finally, co-creation and participatory research methods involving persons with disabilities, urban planners, and policymakers can lead to more grounded, human-centered solutions. Future studies should explore how inclusive governance models can improve the design and monitoring of accessible public space.

Although based on a single site, the insights from Kaimakli Linear Park mirror broader challenges in translating accessibility policy into practice. The findings underscore the value of field-based audits as tools for diagnosing systemic design gaps. As such, this case serves as an illustrative anchor for a broader critical review of urban accessibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and M.K.; methodology; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P; writing—review and editing, M.K., T.D.; supervision, M.K., T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study, in accordance with the policies of Neapolis University Pafos. The research was based primarily on case study observation in a public setting, supplemented by a small number of informal, unrecorded stakeholder interviews. No personal or sensitive data were collected, and no structured survey instruments were used.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interviews. Participants were informed of the voluntary nature of their involvement and the intended academic use of the information shared.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the inclusion of sensitive location-specific and stakeholder-related field notes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| UD | Universal Design |

| PwD | Persons with Disabilities |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| CRPD | Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| EU | European Union |

| N/A | Not Applicable (used in observational tables, possibly implied) |

Appendix A. Detailed Provisions of Regulation 61HA

- Full legislative context and objectives.

- Slope, pathway, tactile paving, and signage requirements.

- Parking space standards (dimensions, access routes).

- Safety requirements for ramps, sidewalks, and public spaces.

In 2017, under Article 19 of the Legislation on the Regulation of Roads and Buildings, the Cyprus Council of Ministers promulgated the Regulations for Roads and Buildings [22]. This legal framework, ratified by the House of Representatives, underwent significant amendments post-2018, most notably the introduction of Regulation 61H and its successor, Regulation 61HA.

Regulation 61HA specifically addresses Accessibility and Safety in Use, mandating comprehensive guidelines for the planning and construction of roads and buildings [21,22]. Its primary objective is to minimize accident and damage risks while ensuring universal accessibility, particularly for individuals with disabilities or mobility impairments, throughout both utilization and operational phases.

Key provisions include:

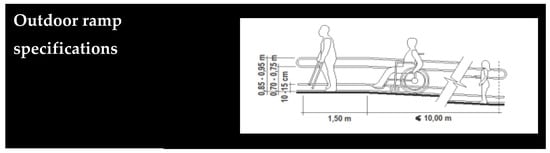

Ramps & Slopes: Gradients calibrated according to elevation change, with strict limits on maximum slope. Requirements for handrails on both sides of ramps exceeding 1.50 m, and double-height handrails for outdoor ramps at 0.70 m and 0.90 m. Intermediate landings required every 10 m.

Pedestrian Pathways: Must have an unobstructed minimum width of 1.20 m, continuous surfaces, and cross slopes of 1–2% for effective drainage. Surfaces should be smooth, compact, and non-slip in both wet and dry conditions.

Signage: Obligatory use of the International Symbol of Accessibility (ISA) on all relevant facilities. Signs must meet standards for contrast, size, and tactile/Braille inclusion, and be mounted at an accessible height.

Parking Standards: Designated accessible spaces marked in blue, with ISA signage positioned at 1.50 m height. Minimum dimensions:

Standard accessible car spaces: 3.30 m × 5.00 m

Wheelchair-adapted vehicle spaces: 4.80 m × 6.00 m

Accessible spaces must connect directly to building entrances or sidewalks via ramps no steeper than 6%.

Sidewalks & Public Squares: Continuous accessible pedestrian zones with minimum free width of 1.20 m and minimum headroom clearance of 2.20 m. Transitions between sidewalks and pavements must use ramps not exceeding 6% slope.

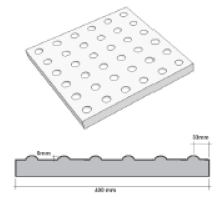

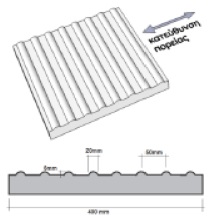

Tactile Paving: Installation of tactile ground surface indicators (guidance, danger, warning types) per CYS EN TS 15209:2008 standards.

Public Gathering Spaces: Minimum ratios of wheelchair-accessible seating (e.g., 3 per 50 seats, 5 per 51–100 seats, and 2% of total seating capacity for larger areas). Accessible changing rooms and shower facilities are also mandated.

Safety Features: Drainage grates must prevent entrapment; floor covering joints must not exceed 0.010 m; tactile warning strips must be placed at 0.40 m from the start of ramps.

These provisions align with broader international standards, including ISO 21542 [11], the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) [19], and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [13]. Despite their legal clarity, however, observations in Kaimakli Linear Park demonstrate significant non-compliance, highlighting the gap between policy intent and practical implementation.

Appendix B. Anthropometric Dimensions

- Dimensions of wheelchair users.

- Wheelchair rotation circle.

- Walking space for individuals with visual impairments.

- Person with a walking aid.

- Person with a child wheelchair.

Table A1.

Basic Anthropometric Dimensions.

Table A1.

Basic Anthropometric Dimensions.

| Parameter | Figure | |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of wheelchair user |  |  |

| Anthropometric dimensions |  |  |

| Basic dimensions of a wheelchair |  |  |

| Wheelchair rotation circle |  | |

| Walking of a person with visual impairment |  | |

| Person with a walking aid |  | |

| Person with a child wheelchair |  | |

Appendix C. Technical Specifications for Universal Design

- Signage standards (International Symbol of Accessibility, Braille, contrast, placement).

- Parking space dimensions and slopes.

- Ramp slope specifications (full table of slope vs. length).

- Sidewalk and surface standards (anti-slip, drainage, tactile floor markings).

- Tactile paving indicators (Guidance, Danger, Warn).

- Requirements for gathering spaces, pedestrian pathways, and crossing points.

Table A2.

Signage for wheelchair users.

Table A2.

Signage for wheelchair users.

| Parameter | Figure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| International accessibility symbol |  | ||

| Signage for parking areas |  |  |  |

| Signage for the existence of a ramp |  | ||

Table A3.

Ramp slope specifications.

Table A3.

Ramp slope specifications.

| Maximum Slope | Maximum Length (m) | Maximum Height (m) | Handrail Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0% | 10.00 | 0.500 | Yes |

| 5.5% | 8.00 | 0.440 | Yes |

| 6.0% | 5.00 | 0.300 | Yes |

| 6.5% | 4.00 | 0.260 | Yes |

| 7.0% | 3.00 | 0.210 | Yes |

| 7.5% | 1.50 | 0.120 | Yes |

| 8.0% | 0.60 | 0.050 | No |

| 8.3% | 0.50 | 0.040 | No |

| 10.0% | 0.30 | 0.030 | No |

| 12.5% | 0.20 | 0.025 | No |

| 13.3% | 0.15 | 0.020 | No |

Figure A1.

Outdoor ramp specifications.

Table A4.

Tactile Ground Surface Indicators.

Table A4.

Tactile Ground Surface Indicators.

| Parameter | Figure |

|---|---|

| Tactile Ground Surface Indicators Type A—GUIDANCE |  |

| Tactile Ground Surface Indicators Type B—DANGER |  |

| Tactile Ground Surface Indicators Type C—WARN |  |

References

- Brussel, M.; Zuidgeest, M.; Pfeffer, K.; Van Maarseveen, M. Access or accessibility? A critique of the urban transport SDG indicator. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Kaur, N. Leaving no one behind: Achieving the sustainable development goals through accessibility for people with disabilities. Int. J. Educ. Commun. Technol. 2024, 4, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Magidimisha-Chipungu, H.H. A Global Perspective on Planning for Disability. In People Living with Disabilities in South African Cities: A Built Environment Perspective on Inclusion and Accessibility; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, E.; Maisel, J. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Story, M.F. Principles of Universal Design. In Universal Design Handbook; The McGraw-Hill Companies: Columbus, OH, USA, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Public Open Space. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/En/Public_open_space (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Kelly, O.; Buckley, K.; Lieberman, L.J.; Arndt, K. Universal Design for Learning-A framework for inclusion in Outdoor Learning. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2022, 25, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, T.; Le Grand, J.; Piachaud, J. Degrees of exclusion: Developing a dynamic, multidimensional. In Understanding Social Exclusion; Hills, J., Le Grand, J., Piachaud, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta, R.; Sarris, C.; Signoretta, P.; Moughtin, J.C. Urban Design: Method and Techniques; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili, M.; Sheydayi, A.; Jamalabadi, F. A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Content Analysis Applications in Urban Planning Research: Proposing a Mixed Method Approach. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 04025020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21542:2021; Building Construction—Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Praça, B. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). In Fundamentals of Planning Cities for Healthy Living; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 15+35+38+75+102+109+138. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, A. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Eur. J. Health Law 2007, 14, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imrie, R. Universalism, universal design and equitable access to the built environment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- City of London. Designing Inclusive Public Spaces: A Guide; City of London: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, H.; Moore, A.; Edwards, C.; Horgan, L. Community Parks and Playgrounds: Intergenerational Participation Through Universal Design; Centre for Excellence in Universal Design: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kopeva, A.; Ivanova, O.; Zaitseva, T. Application of Universal Design principles for the adaptation of urban green recreational facilities for low-mobility groups (Vladivostok case-study). In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 463, p. 022018. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, T.M. The americans with disabilities act: The move to integration. Temp. LR 1991, 64, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the Accessibility Requirements for Products and Services. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L0882 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Regulation for Accessibility of the Public Places Build Environment. Available online: https://www.cylaw.org/nomoi/arith/2017_1_111.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Accessibility: Principles And Guidelines. Available online: https://opak.org.cy/prosvasimotita/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Null, R. (Ed.) Universal Design: Principles and Models; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guidance on Use of the International Symbol of Accessibility, Under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Architectural Barriers Act. 27 March 2017. Available online: https://www.access-board.gov/files/aba/guides/ISA-guidance.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Silver, H. Understanding social inclusion and its meaning for Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 45, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, E.L.; Renganathan, R.; Toth, B.N.; Cohen, A.J.; Bajcsy, A.V.; Bateman, A.; Jennings, M.C.; Khattar, A.; Kuo, R.S.; Lee, F.A.; et al. A review of principles in design and usability testing of tactile technology for individuals with visual impairments. Assist. Technol. 2017, 29, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V.; Mahato, B. Designing urban parks for inclusion, equity, and diversity. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2021, 14, 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, D. WOT analysis. In Handbook of Improving Performance in the Workplace: Volumes 1–3; International Society for Performance Improvement: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzakis, T.; Alčiauskaitė, L.; König, A. The needs and requirements of people with disabilities for frequent movement in cities: Insights from qualitative and quantitative data of the TRIPS project. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Design governance: Theorizing an urban design sub-field. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Friemel Thomas, N. The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velho, R.; Holloway, C.; Symonds, A.; Balmer, B. The effect of transport accessibility on the social inclusion of wheelchair users: A mixed method analysis. Soc. Incl. 2016, 4, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.E.; Monsalve, A.; Morán, M.L.; Alcedo, M.Á.; Lombardi, M.; Schalock, R.L. Measurable indicators of CRPD for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities within the quality of life framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froehlich, J.E.; Li, C.; Hosseini, M.; Miranda, F.; Sevtsuk, A.; Eisenberg, Y. The Future of Urban Accessibility: The Role of AI. In Proceedings of the 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, St. John‘s, NL, Canada, 27–30 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Prandi, C.; Barricelli, B.R.; Mirri, S.; Fogli, D. Accessible wayfinding and navigation: A systematic mapping study. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, S.; Hutson, P.; Hutson, J. Navigating Life: Neuroscience and Inclusive Design in Wayfinding Systems. Int. J. Clin. Case Stud. Rep. 2024, 6, 90. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/faculty-research-papers/690/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Flacke, J.; Hoefsloot, F.I.; Pfeffer, K. Inclusive Digital Planning–Co-designing a collaborative mapping tool to support the planning of accessible public space for all. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2025, 121, 102310. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, M.D.L.Á. Information design for supporting collaborative communities. Des. J. 2017, 20, S3262–S3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).