A Multi-Scale Suitability Assessment Framework for Deep Geological Storage of High-Salinity Mine Water in Coal Mines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Research Status Domestically and Internationally

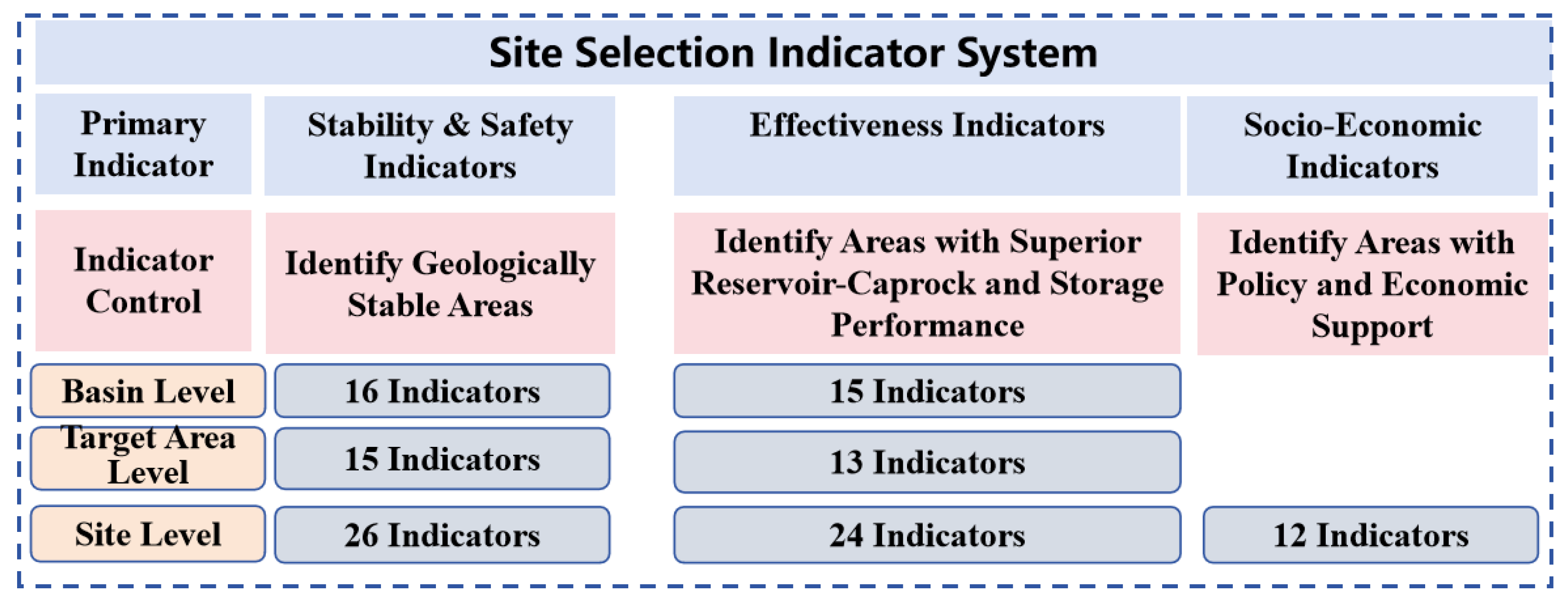

3. Suitability Assessment Indicators for Mine Water Geological Storage

3.1. Stability and Safety (Engineering Geological Conditions)

3.2. Effectiveness (Effective Storage Potential)

3.3. Socio-Economics (Socio-Economic Context)

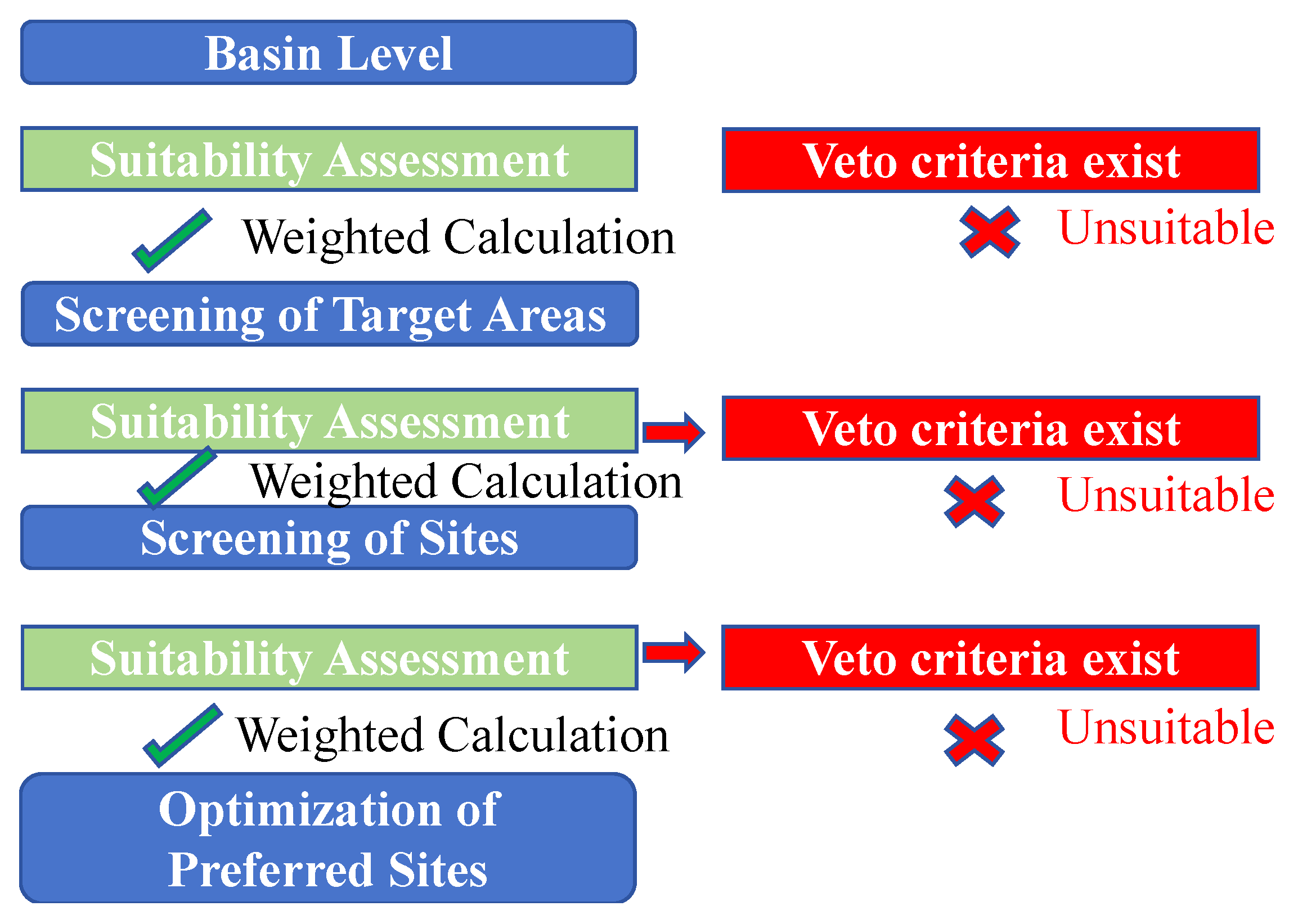

4. Construction of the Geological Storage Suitability Evaluation System at Multiple Scales

5. Methodology for Constructing a Weighting System for the Suitability Assessment of Mine Water Geological Storage

5.1. Suitability Assessment Methodology

- (1)

- Construction of the Hierarchical Structure Model

- (2)

- Construction of Judgment Matrices and Weight Calculation

- (3)

- Consistency Check

5.2. Multi-Scale Weight Adaptation Method

5.3. Comprehensive Suitability Index Calculation and Classification

- (1)

- Indicator Standardization and Scoring

- (2)

- “One-vote veto” Mechanism

- (3)

- Multi-scale Suitability Index Calculation

- (4)

- Suitability Classification

6. Conclusions

7. Challenges and Future Perspectives

7.1. Key Challenges and Limitations

7.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolkersdorfer, C.; Bowell, R. Contemporary reviews of mine water studies in Europe. Mine Water Environ. 2004, 23, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, H. Mine water pollution—An overview of problems and control strategies in the United Kingdom. Water Sci. Technol. 1983, 15, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Song, S.; Liu, L.; Gu, L.; Wei, J. Change of coal energy status and green and low-carbon development under the “dual carbon” goal. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 2599–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhu, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, L. Study on Issues and Countermeasures in Coal Measures Mine Water Resources Exploitation and Utilization. Coal Geol. China 2020, 32, 9–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wu, B.; Fang, H. Coalmine Ordovician Limestone Water Treatment and Reclamation—A Case Study of Panji Coalmine No.2, Huainan. Coal Geol. China 2020, 32, 52–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R. Simulation Study on Mine Water Depths Transfer Hydrogeochemical Variation—A Case Study of Northeastern Ordos Basin. Coal Geol. China 2022, 34, 29–33+62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. High Suspended Substance Content Mine Water Governance and Reutilization Technological Research. Coal Geol. China 2022, 34, 48–50+80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Qi, K.; Li, X.; Xu, H. Treatment technology and resource utilization of mine water with high salinity in western China. Coal Geol. China 2020, 32, 68–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhang, C.; Wu, W.; Wang, D.; Geng, J.; Fu, Y. Prospect of Deep Well Injection for Treatment of Coal Mine Drainage Brine Wastewater. China Water Wastewater 2020, 36, 40–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Du, S.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liang, C.; Liu, J.; Song, S. Assessment of Leakage Risk Probability of Deep Geological Storage Technology. Coal Geol. China 2025, 37, 62–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowska, M.; Brudzinski, M.; Friberg, P.; Skoumal, R.; Baxter, N.; Currie, B. Maturity of nearby faults influences seismic hazard from hydraulic fracturing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1720–E1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shalabi, E.; Sepehrnoori, K. A comprehensive review of low salinity/engineered water injections and their applications in sandstone and carbonate rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 139, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, S.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, K.; Wan, X.; Cui, S. Experiment on CO2-brine-rock interaction during CO2 injection and storage in gas reservoirs with aquifer. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 413, 127567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Underground Injection Technology and Its Application in the United States. Environ. Prot. 2007, 35, 76–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Underground Injection Control Regulations. 10 October 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/uic/underground-injection-control-regulations (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, M. Environmental Legal Control on Deep Well Injection. Environ. Prot. 2004, 32, 15–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Gao, Z.; Zang, Y. Review of Research on Underground Injection Technology for Industrial Hazardous Waste Disposal both at Home and Abroad. Res. Environ. Sci. 2018, 31, 832–839. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, H. Water Management in the Mining Industry; Anglo American: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, R.F.; Fernández, D.L. Artificial Recharge of Groundwater in Mining. In Proceedings of the International Mine Water Association Symposium–Mine Water and Innovative Thinking, Sydney, NS, Canada, 5–9 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 27914:2017; Carbon Dioxide Capture, Transportation and Geological Storage—Geological Storage. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/64148.html (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- NETL. Best Practices: Site Screening, Site Selection, and Site Characterization for Geologic Storage Projects. 2017. Available online: https://www.netl.doe.gov/sites/default/files/2018-10/BPM-SiteScreening.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- WRI. Guidelines for Carbon Dioxide Capture, Transport, and Storage. 2008. Available online: https://www.wri.org/research/guidelines-carbon-dioxide-capture-transport-and-storage (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Bachu, S. Screening and ranking of sedimentary basins for sequestration of CO2 in geological media in response to climate change. Environ. Geol. 2003, 44, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.; Arts, R.; Bernstone, C.; May, F.; Thibeau, S.; Zweigel, P. Best Practice for the Storage of CO2 in Saline Aquifers: Observations and Guidelines from the SACS and CO2 Store Projects; British Geological Survey: Nottingham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, C.M. Screening and ranking framework for geologic CO2 storage site selection on the basis of health, safety, and environmental risk. Environ. Geol. 2008, 54, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratzloup, S.; Bonijoly, D.; Brosse, E.; Dreux, R.; Garcia, D.; Hasanov, V.; Lescanne, M.; Renoux, P.; Thoraval, A. A site selection methodology for CO2 underground storage in deep saline aquifers: Case of the Paris Basin. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 2929–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodosta, T.; Litynski, J.; Plasynski, S.; Hickman, S.; Frailey, S.; Myer, L. U.S. Department of energy’s site screening, site selection, and initial characterization for storage of CO2 in deep geological formations. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 4664–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, R.; Yaw, S.; Hoover, B.; Ellett, K. SimCCS: An open–source tool for optimizing CO2 capture, transport, and storage infrastructure. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 124, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Callas, C.; Saltzer, S.D.; Kovscek, A. Assessment of oil and gas fields in California as potential CO2 storage sites. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Bai, B.; Fang, Z. Ranking And Screening of CO2 Saline Aquifer Storage Zones in China. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2006, 25, 963–968. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Geological safety evaluation method for CO2 geological storage in deep saline aquifer. Geol. China 2011, 38, 786–792. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Administrative Center for China’s Agenda 21; Center for Hydrogeology and Environmental Geology Survey (CGS). Research on Site Selection Guidelines for Carbon Dioxide Geological Storage in China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Wen, D.; Zhang, S. Suitability Assessment and Demonstration Project of Carbon Dioxide Geological Storage in China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Chen, J. The site selection geological evaluation of the CO2 storage of the deep saline aquifer. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96, 1868–1882. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Jing, T.; You, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, J. Site Selection Strategy for An Annual Million-Ton Scale CO2 Geological Storage in China. Geoscience 2022, 36, 1414–1431. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Zheng, B.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Huang, T.; Guo, S.; Fu, L.; Dong, P.; Zhao, H. Geological evaluation for the carbon dioxide geological utilization and storage (CGUS) site: A review. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 1917–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Zheng, B.; Lu, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Guo, S. Investigation Of Indexes System And Suitability Evaluation For Cabon Dioxide Geological Storage Site. Quat. Sci. 2023, 43, 523–550. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Han, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, B.; Hu, F.; Wang, Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, S. Evaluating the key controls on CO2 geologic storage site. Nat. Gas Explor. Dev. 2024, 47, 95–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Wang, H.; Lai, X.; Ma, J.; Luo, S.; Li, L.; Ding, Z. Site selection evaluation system for CO2 storage in low-porosity and low-permeability saline layers: A case study of the Ordos Basin. Coal Geol. Explor. 2025, 53, 99–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Jing, M.; Li, X. Suitability Evalyation Method For CO2 Geological Stogage Sites Based On Muliti-criteria Decisoin-making. Quat. Sci. 2023, 43, 551–559. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xie, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xian, X.; Liu, Q. Influence of Supercritical CO2 Exposure on CH4 and CO2 Adsorption Behaviors of Shale: Implications for CO2 Sequestration. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 6073–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ning, Z.; Wang, Q.; Qi, R.; Zeng, Y.; Qin, H.; Ye, H.; Zhang, W. Molecular simulation of adsorption behaviors of methane, carbon dioxide and their mixtures on kerogen: Effect of kerogen maturity and moisture content. J. Fuel 2018, 211, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, L.; Elsworth, D.; Gan, Q. CO2/CH4 Competitive Adsorption in Shale: Implications for Enhancement in Gas Production and Reduction in Carbon Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 9328–9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, J.G.; Isselhardt, B.J.; Cappuccio, J.D. The Analytic Hierarchy Process in Medical Decision Making: A Tutorial. Med. Decis. Mak. 1989, 9, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Labib, A. Review of the main developments in the analytic hierarchy process. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 14336–14345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, O.S.; Kumar, S. Analytic hierarchy process: An overview of applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 169, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiru, H.; Wagari, M. Evaluation of data-driven model and GIS technique performance for identification of Groundwater Potential Zones: A case of Fincha Catchment, Abay Basin, Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 37, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, G.; Pouliaris, C.; Kahuda, D.; Vasile, T.A.; Manea, V.A.; Zaun, F.; Panteleit, B.; Dadaser-Celik, F.; Positano, P.; Nannucci, M.S.; et al. Spatial data management and numerical modelling: Demonstrating the application of the QGIS-integrated FREEWAT platform at 13 case studies for tackling groundwater resource management. Water 2020, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafila, O.; Ranganai, T.; Moalafhi, D.B.; Moreri, K.; Maphanyane, J. Investigating groundwater recharge potential of Notwane catchment in Botswana using geophysical and geospatial tools. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 40, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Tatomir, A.; Oehlmann, S.; Giese, M.; Sauter, M. Numerical Benchmark Studies on Flow and Solute Transport in Geological Reservoirs. Water 2022, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Jeen, S.-W.; Hwang, H.-T.; Lee, K.-K. Changes in Geochemical Composition of Groundwater Due to CO2 Leakage in Various Geological Media. Water 2020, 12, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W.; Liao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. A Review of Hydromechanical Coupling Tests, Theoretical and Numerical Analyses in Rock Materials. Water 2023, 15, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Tan, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, W. Effects of Coal Mining Activities on the Changes in Microbial Community and Geochemical Characteristics in Different Functional Zones of a Deep Underground Coal Mine. Water 2024, 16, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.; Pan, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, H. An Analytical Solution for Characterizing Mine Water Recharge of Water Source Heat Pump in Abandoned Coal Mines. Water 2024, 16, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lao, J.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, H. Intelligent Prediction of Water-CO2 Relative Permeability in Heterogeneous Porous Media Towards Carbon Sequestration in Saline Aquifers. Water 2025, 17, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranter, M.; De Lucia, M.; Wolfgramm, M.; Kühn, M. Barite Scale Formation and Injectivity Loss Models for Geothermal Systems. Water 2020, 12, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stability & Safety | Geothermal Heat Flow (mW/m2) | [30, 50) | [50, 90] | >90 |

| Geothermal Gradient (°C/100 m) | <2 | [2, 4] | >4 | |

| Development of Active Faults | Far from active fault zone (>25 km), no active faults pass through | Relatively close to active faults (<25 km), no active faults pass through or Neogene faults pass through with insignificant Holocene activity | Active faults pass through, but they are small-scale, weakly active, or located on a major active fault zone or its intersection, with strong fault activity | |

| Volcanic Development Zone | Low-occurrence volcanic zone | Occurring volcanic zone | High-occurrence volcanic zone | |

| Distance to Volcanic Zone (km) | >250 | [25, 250] | <25 | |

| Peak Ground Acceleration (g) | <0.05 | [0.05, 0.1] | >0.1 | |

| Historical Seismicity | Historical seismic gap | M ≤ 6 | M > 6 | |

| Distance to Seismic Zone (km) | >250 | [25, 250] | <25 | |

| Caprock Lithology | Gypsum rock, mudstone/calcareous mudstone | Sandy mudstone, silty mudstone, argillaceous siltstone, argillaceous sandstone | Argillaceous siltstone, argillaceous sandstone, fractured limestone, coarse clastic sandstone | |

| Burial Depth (Main Caprock) (m) | [800, 1200) | [1200, 3500] | >3500 or <800 | |

| Thickness (Single layer of main caprock) (m) | >100 | [30, 100] | <30 | |

| Caprock Permeability (×10−3 μm2) | <0.0001 | [0.0001, 0.01] | >0.01 | |

| Continuity | Continuous, stable | Relatively continuous or moderately continuous, relatively stable | Poorly continuous or discontinuous, relatively unstable or unstable | |

| Number of Layers | Multiple sets, good quality | Multiple sets or one set, relatively good quality | One set or none, poor quality | |

| Reservoir-Caprock Geochemical Compatibility | Similar water chemistries, no potential for scaling/dissolution | Minor scaling/dissolution risk, manageable via engineering controls | Severe risk of scaling or mineral dissolution | |

| Hydrodynamic Effect | Hydraulic confinement | Hydraulic sealing | Hydraulic migration and dispersion |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Tectonic Unit Area (km2) | >5000 | [500, 5000] | <500 |

| Sedimentary Formation Thickness (m) | >3500 | [1600, 3500] | <1600 | |

| Reservoir Burial Depth (m) | [800, 3500] | [800, 3500] | >3500 or <800 | |

| Reservoir Thickness (m) | >100 | [20, 100] | <20 | |

| Reservoir Porosity (%) | >5 | [1, 5] | <1 | |

| Reservoir Permeability (×10−3 μm2) | >1 | [0.01, 1] | <0.01 | |

| Reservoir Sand-to-Shale Ratio (%) | >60 | [20, 60] | <20 | |

| Interlayer Heterogeneity (Sandbody Continuity) (m) | >2000 | [600, 2000] | <600 | |

| Number of Reservoir Layers (Regional) | Multiple sets | Potentially exist | None | |

| Number of Reservoir-Caprock Combinations (Regional) | Multiple sets | Potentially exist | None | |

| Exploration Maturity | Under development | Moderate exploration maturity | Low or no exploration | |

| Data Support Status | Sufficient and reliable data | Moderate data | Insufficient data | |

| Resource Potential (Oil, Gas, Coal Scale) | Large | Sufficient, generally reliable | Moderate | |

| Storage Potential (×108 t) | >50 | [50, 150] | <50 | |

| Storage Potential per Unit Area (×104 t/km2) | >150 | [0.5, 50] | <0.5 |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stability & Safety | Geothermal Heat Flow (mW/m2) | [30, 50) | [50, 90] | >90 |

| Geothermal Gradient (°C/100 m) | <2 | [2, 4] | >4 | |

| Development of Active Faults | No active faults within 25 km, and no active faults exist within the peripheral 25 km range | No active faults within the target area, but active faults exist within the peripheral 25 km range | Whether active faults develop within the target area and its periphery remains unclear | |

| Peak Ground Acceleration (g) | <0.05 | [0.05, 0.1] | >0.1 | |

| Historical Seismicity | Historical seismic gap | M ≤ 6 | M > 6 | |

| Caprock Lithology | Gypsum rock, mudstone, calcareous mudstone, evaporite | Sandy mudstone, silty mudstone, argillaceous siltstone, argillaceous sandstone | Argillaceous siltstone, argillaceous sandstone, shale, tight limestone | |

| Caprock Burial Depth (m) | <1000 | [1000, 2700] | >2700 | |

| Thickness (Single layer) (m) | >20 | [10, 20] | <10 | |

| Thickness (Cumulative) (m) | >300 | [150, 300] | <150 | |

| Caprock Permeability (×10−3 μm2) | <0.0001 | [0.0001, 0.01] | >0.01 | |

| Mechanical Stability | Stable | Relatively stable | Unstable (one-vote veto) | |

| Distribution Continuity | Continuous | Relatively continuous | Relatively discontinuous | |

| Number of Layers | Multiple sets | One set | None (one-vote veto) | |

| Reservoir-Caprock Geochemical Compatibility | Similar water chemistries, no potential for scaling/dissolution | Minor scaling/dissolution risk, manageable via engineering controls | Severe risk of scaling or mineral dissolution | |

| Hydrodynamic Effect | Hydraulic confinement | Hydraulic sealing | Hydraulic migration and dispersion (one-vote veto) |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Reservoir Thickness (m) | >80 | [30, 80] | [10, 30) |

| Reservoir Porosity (Average) (%) | >15 | [10, 15] | [5, 10) | |

| Reservoir Permeability (Average) (×10−3 μm2) | >5 | [1, 5] | <1 | |

| Reservoir Permeability Variation Coefficient | <0.5 | [0.5, 0.6] | >0.6 | |

| Interlayer Heterogeneity (Sandbody Continuity) (m) | >2000 | [600, 2000] | <600 | |

| Reservoir Distribution Continuity (m) | >2000 | [600, 2000] | <600 | |

| Reservoir Body Layered Distribution | Easily migrates to positions with relatively lower pressure or lower structure within the layered reservoir body | |||

| Number of Reservoir Layers | Multiple sets | Potentially exist | None | |

| Located at Reservoir-Caprock Interface? | No | No | Yes | |

| Multi-layer Caprock-Reservoir Form | Multi-layer caprock-reservoir form, which may increase or decrease leakage risk | |||

| Single-layer Caprock-Reservoir Form | Single-layer caprock-reservoir form with thick caprock, but once breached, the storage system fails completely | |||

| Storage Potential (×106 t) | >50 | [0.5, 50] | <0.5 | |

| Storage Potential per Unit Area (×104 t/km2) | >100 | [10, 100] | <10 | |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stability & Safety | Geothermal Heat Flow (mW/m2) | <50 | [50, 70] | >70 |

| Geothermal Gradient (°C/100 m) | <2 | [2, 3] | >3 | |

| Development of Active Faults | No active faults within 25 km, and no active faults exist within the peripheral 25 km range | No active faults within the site area, but active faults exist within the peripheral 25 km range | Whether active faults develop within the site area and its periphery remains unclear | |

| Development of Faults and Fractures | Limited fractures, no faults | Moderate fracture development, no faults | Large fractures, moderate fault development | |

| Peak Ground Acceleration (g) | <0.05 | [0.05, 0.1] | >0.1 | |

| Historical Seismicity | Historical seismic gap | M ≤ 6 | M > 6 | |

| Geomorphological Type | Fixed dunes | Bedrock hills or semi-fixed dunes | Water bodies | |

| Topographic Slope (°) | [0, 10) | [10, 25] | >25 | |

| Caprock Lithology | Evaporites or tight mudstone | Argillaceous rocks | Shale and tight limestone | |

| Fault/Fracture Development in Caprock | Limited faults and fractures | Moderate faults, moderate fractures | Major faults, major fractures (one-vote veto) | |

| Buffer Layers | Multiple sets | One set | None | |

| Reservoir Lithology | Clastic rock | Clastic rock, carbonate rock mixed | Carbonate rock | |

| Burial Depth (Main Caprock) (m) | [800, 1200) | [1200, 1700] | >1700 | |

| Thickness (Single layer of main caprock) (m) | >100 | [50, 100] | <50 | |

| Permeability (×10−3 μm2) | <0.01, stable | [0.01, 1] | >1 | |

| Mechanical Stability | Stable | Relatively stable | Unstable (one-vote veto) | |

| Distribution Continuity | Regionally continuous distribution | Basically continuous distribution | Discontinuous, localized distribution | |

| Number of Layers | Multiple sets, good quality | Multiple sets, moderate quality | One set | |

| Reservoir Sedimentary Facies | Fluvial, Delta | Turbidite, Alluvial Fan | Beach Bar and Biogenic Reef | |

| Reservoir Pressure Coefficient | <0.9 | [0.9, 1.1] | >1.1 | |

| Reservoir-Caprock Geochemical Compatibility | Similar water chemistries, no potential for scaling/dissolution | Minor scaling/dissolution risk, manageable via engineering controls | Severe risk of scaling or mineral dissolution | |

| Distance to Coal Mining Subsidence Area (km) | >25 | [20, 25] | <20 | |

| Distance to Jointed/Fractured Zone (km) | >25 | [20, 25] | <20 | |

| Susceptibility to Geological Hazards | Low susceptibility | Low-Medium susceptibility | High susceptibility (one-vote veto) | |

| Located in mining subsidence area, karst collapse area, land subsidence area, desert activity area, volcanic activity area? | No | No, but potential impact | Yes (one-vote veto) | |

| Below the highest water level of rivers, lakes, reservoirs, or floodplain? | No | No, but potential impact | Yes (one-vote veto) |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Reservoir Thickness (Main Reservoir) (m) | >80 | [30, 80] | <30 |

| Reservoir Formation Dip Angle | <10° | [10°, 15°] | >15° | |

| Reservoir Sand-to-Shale Ratio | ≥60% | 50–60% | <50% | |

| Sandstone Porosity (%) | >5 | [0.1, 5] | <0.1 | |

| Sandstone Permeability (×10−3 μm2) | >1 | [0.01, 1] | <0.01 | |

| Reservoir Permeability Variation Coefficient | <0.5 | [0.5, 0.6] | >0.6 | |

| Interlayer Heterogeneity (Sandbody Continuity) (m) | >1200 | [600, 1200] | <600 | |

| Reservoir Distribution Continuity (m) | >2000 | [600, 2000] | <600 | |

| Reservoir Body Layered Distribution | Easily migrates to positions with relatively lower pressure or lower structure within the layered reservoir body | |||

| Number of Reservoir Layers | Multiple sets | Potentially exist | None (one-vote veto) | |

| Hydrodynamic Effect | Hydraulic sealing | Hydraulic confinement | Hydraulic migration and dispersion | |

| Reservoir Injectivity (Main Reservoir) (m3/h) | >100 | [50, 100] | <50 | |

| Number of Reservoir-Caprock Combinations | Multiple sets | Potentially exist | None (one-vote veto) | |

| Original Formation Water Salinity (g/L) | (10, 50] | [3, 10] | <3 or >50 | |

| Storage Potential (×104 t) | >900 | [300, 900] | <300 | |

| Storage Potential per Unit Area (×104 t/km2) | >100 | [30, 100] | <30 | |

| Well Service Life (years) | >10 | [5, 10] | <5 | |

| Effective Storage Coefficient (%) | >8 | [2, 8] | <2 | |

| Injection Index (m3) | >10−14 | [10−15, 10−14] | <10−15 | |

| Injection Well Operating Pressure (Pa) | Less than caprock breakthrough pressure and failure pressure of well materials | Equal to caprock breakthrough pressure and failure pressure of well materials | Greater than caprock breakthrough pressure and failure pressure of well materials | |

| Injection Well Volume (m3/h) | Less than storage capacity | Equal to storage capacity | Exceeds storage capacity | |

| Injection Well Rate (m3/h) | >300 | 50~300 | <50 | |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Suitable | Moderate | Unsuitable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-economics | Population Density (persons/km2) | <25 | [25, 50] | >50 |

| Distance to Residential Area (m) | >1200 | [800, 1200] | <800 | |

| Public Acceptance and Regulations | High public acceptance, sound regulations | Moderate public acceptance, regulations need modification | Public opposition (one-vote veto) | |

| Current Land Use | Unused land such as desert | Grassland, woodland, cultivated land, garden land | Residential, industrial/mining land, transportation land, water bodies, etc. | |

| Economic Viability | Good economic viability | Moderate economic viability | Not economically viable (one-vote veto) | |

| Water Resource Protection and Utilization Policies | Compliant | Compliant | Non-compliant (one-vote veto) | |

| Located in Protected Area? | No, and >10 km away | No, but potential impact | Yes (one-vote veto) | |

| Status of Protected Plant Species | None, Low | Few, Moderate | Many, High | |

| Mine Water Inflow Volume | >100 m3 | [50, 100] m3 | <50 m3 | |

| Mine Water Quality | TDS ≥ 10,000, almost no organic matter | 10,000 ≥ TDS > 1000, almost no organic matter | TDS < 1000, contains organic matter | |

| Transport Distance | Underground or <100 m | 100~200 m | >200 m | |

| Mineral Resource Status in Formation | No mineral resources overlain | Minerals present, but no mutual impact | Mineral resources overlain (one-vote veto) |

| Criterion | Stability & Safety | Effectiveness | Socio-Economic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability & Safety | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Effectiveness | 1/1.5 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Socio-economic | 1/2 | 1/1.5 | 1 |

| Suitability Class | Composite Index (S) | Description and Engineering Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Suitable | S > 4.0 | Site conditions are superior, with low risk and significant benefits. Recommended for priority consideration and may proceed directly to the next phase. |

| Moderate | 3.0 ≤ S ≤ 4.0 | Site conditions are generally adequate but have shortcomings. Detailed demonstration is recommended, requiring in-depth analysis of weak points and development of mitigation measures. |

| Unsuitable | S < 3.0 | Site has multiple critical deficiencies, high risk, or poor effectiveness. Not recommended as a storage site and should be excluded from further consideration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Z.; Du, S.; Ren, S.; Che, Q.; Zhang, X.; Fan, Y. A Multi-Scale Suitability Assessment Framework for Deep Geological Storage of High-Salinity Mine Water in Coal Mines. Water 2025, 17, 3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233407

Jiang Z, Du S, Ren S, Che Q, Zhang X, Fan Y. A Multi-Scale Suitability Assessment Framework for Deep Geological Storage of High-Salinity Mine Water in Coal Mines. Water. 2025; 17(23):3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233407

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Zhe, Song Du, Songyu Ren, Qiaohui Che, Xiao Zhang, and Yinglin Fan. 2025. "A Multi-Scale Suitability Assessment Framework for Deep Geological Storage of High-Salinity Mine Water in Coal Mines" Water 17, no. 23: 3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233407

APA StyleJiang, Z., Du, S., Ren, S., Che, Q., Zhang, X., & Fan, Y. (2025). A Multi-Scale Suitability Assessment Framework for Deep Geological Storage of High-Salinity Mine Water in Coal Mines. Water, 17(23), 3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233407