Advancements in Microbial Nitrogen Pathways for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

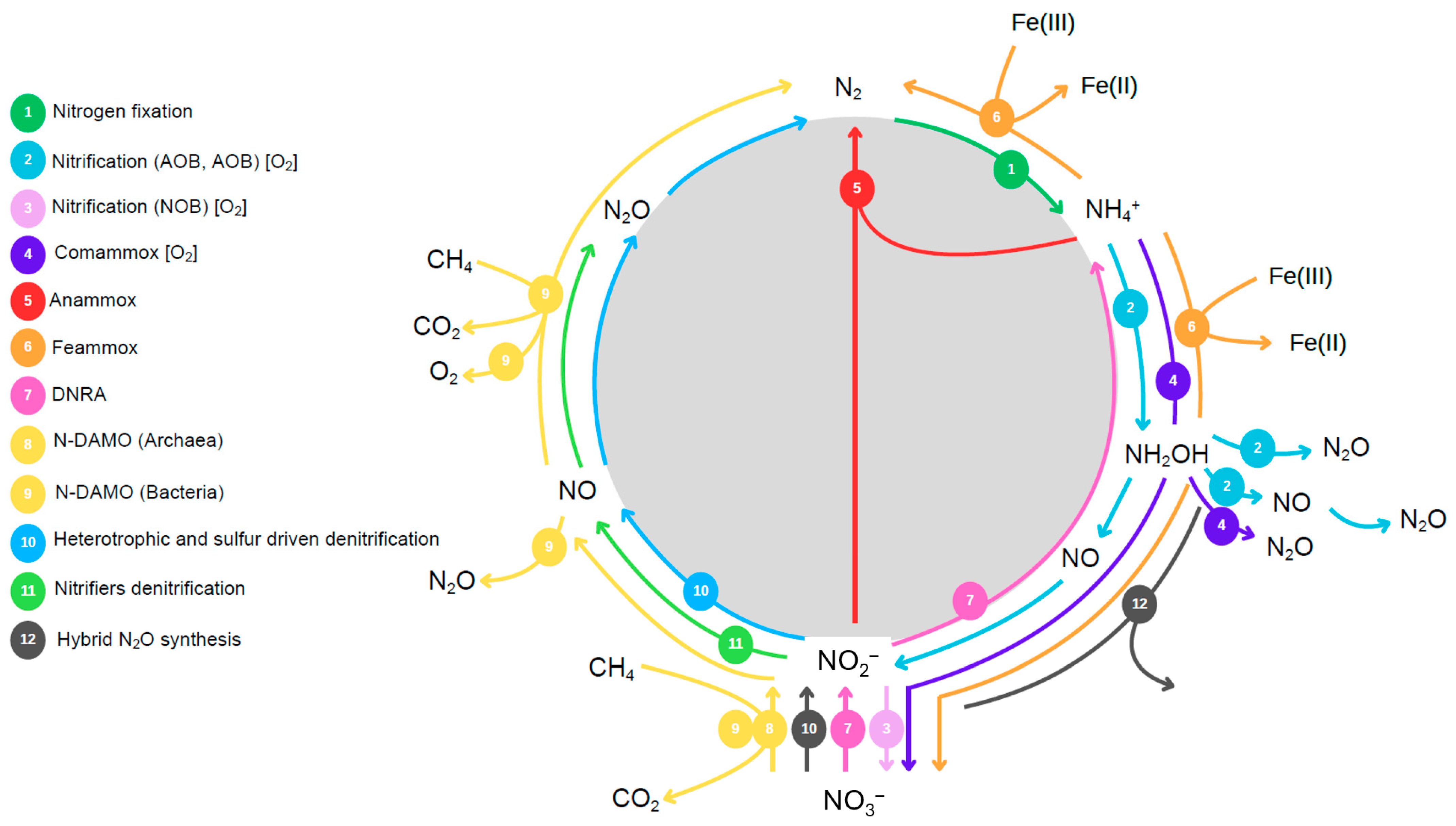

1. Introduction

Review Methodology for Literature Survey

2. Implications of Complete Ammonia (NH3) Oxidation Bacterial Community in Wastewater Treatment

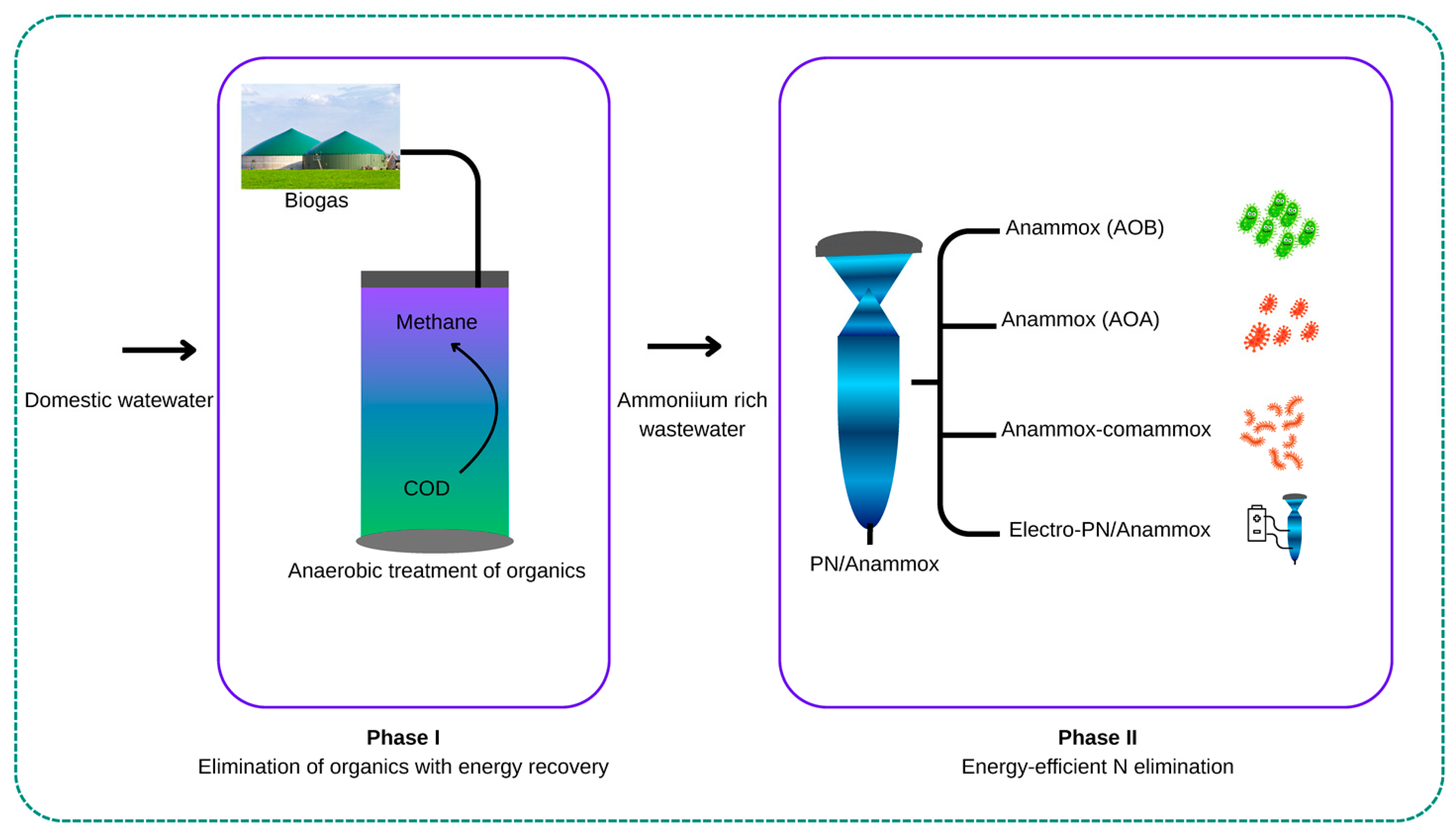

3. Synergistic Potential of Comammox-Anammox Systems for Energy-Efficient Nitrogen Removal

4. Advancing Comammox-Anammox Integration in Wastewater Treatment

5. Emerging Insights into Anammox-Based N Removal for Domestic Wastewater Treatment

6. Domestic Wastewater Treatment and Challenges Associated with PN/A

7. Feammox Pathways for the Treatment of Wastewater

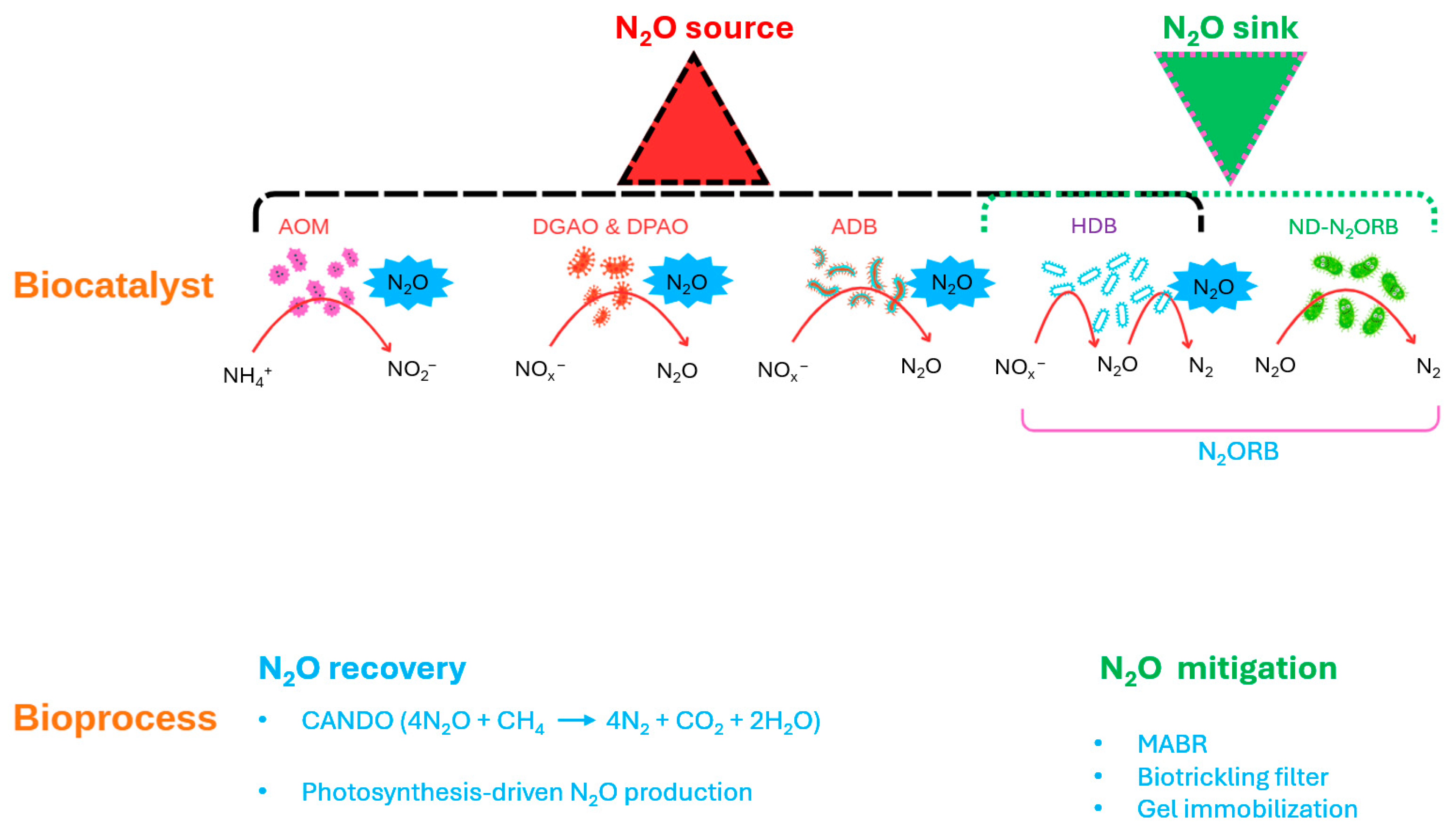

8. Understanding and Mitigating N2O Emissions in Wastewater Systems

8.1. Biology of N2O Production and Consumption

- Minimizing the activity of dominant N2O-producing microorganisms, particularly AOMs and denitrifying PAOs/GAOs.

- Enhancing the activity and abundance of ND-N2ORB, especially those with oxygen-tolerant and high-affinity Nos systems.

- Improving the N2O sink potential of HDB through selective enrichment, adaptive evolution, or bioengineering strategies.

8.2. Process-Level Mitigation in Reactors

8.3. Post-Treatment, Off-Gas Capture, and Resource Recovery

- (i)

- Optimization of system design to enhance process stability, efficiency, and adaptability across variable wastewater types, including leachate, manure, and nightsoil [89].

- (ii)

- Reduction in operational complexity and costs, particularly by refining environmental conditions necessary for the metabolic activities of DGAOs and DPAOs.

- (iii)

- Integration of CANDO with existing wastewater infrastructure, allowing for hybrid systems that combine N2O mitigation and recovery in a single treatment framework.

9. Future Directions for N2O Mitigation and Technology Integration

10. Quantitative Comparison of Emerging and Conventional N Removal Processes

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuypers, M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, J.; Liao, J.; Xu, X.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Peng, J.; Niu, S. Plant nitrogen uptake preference and drivers in natural ecosystems at the global scale. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.R.; Brady, N.C. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban, M.; Nunez-Delgado, A. Soil adsorption potential: Harnessing Earth’s living skin for mitigating climate change and greenhouse gas dynamics. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.K.; Straka, L. New directions in biological nitrogen removal and recovery from wastewater. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoo, R.; Mallikarjuna, S.B.; Hemachar, N. Ecosystem and Climate Change Impacts on the Nitrogen Cycle and Biodiversity. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Hatano, R.; Wu, Y.; Shaaban, M. Editorial: Nitrogen dynamics and load in soils. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1197902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Wang, W.; Qin, D.; Luo, H.; Qin, F.; Li, K.; Weng, H.; Zhang, C. Revisiting the microbial nitrogen-cycling network: Bibliometric analysis and recent advances. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodirsky, B.L.; Popp, A.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Dietrich, J.P.; Rolinski, S.; Weindl, I.; Schmitz, C.; Müller, C.; Bonsch, M.; Humpenöder, F. Reactive nitrogen requirements to feed the world in 2050 and potential to mitigate nitrogen pollution. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M. Microbial pathways of nitrous oxide emissions and mitigation approaches in drylands. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoregie, A.I.; Silini, M.O.E.; Wong, L.S.; Rajasekar, A. Nitrogen Eutrophication in Chinese Aquatic Ecosystems: Drivers, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Jofra, A.; Pérez, J.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C. Hydroxylamine and the nitrogen cycle: A review. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parret, L.; Simoens, K.; Horemans, B.; De Vrieze, J.; Smets, I. Establishing a co-culture aggregate of N-cycle bacteria to elucidate flocculation in biological wastewater treatment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, F. Energy self-sufficient wastewater treatment plants: Feasibilities and challenges. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 3741–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, H.; Law, Y.Y.; Guest, J.S.; Rabaey, K.; Batstone, D.; Laycock, B.; Verstraete, W.; Pikaar, I. Mainstream ammonium recovery to advance sustainable urban wastewater management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11066–11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Shaw, D.R.; Gonzalez, J.T.; Guadarrama, C.B.; Saikaly, P.E. Emerging biotechnological applications of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1128–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogler, A.; Farmer, M.; Simon, J.A.; Tilmans, S.; Wells, G.F.; Tarpeh, W.A. Systematic evaluation of emerging wastewater nutrient removal and recovery technologies to inform practice and advance resource efficiency. ACS EST Eng. 2021, 1, 662–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.E.; Lücker, S. Complete ammonia oxidation: An important control on nitrification in engineered ecosystems? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 50, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleper, C.; Simon, K. Analysis of biomass productivity and physiology of Nitrososphaera viennensis grown in continuous. Metab. Pathw. Archaea 2025, 6, 1076342. [Google Scholar]

- Daims, H.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Pjevac, P.; Han, P.; Herbold, C.; Albertsen, M.; Jehmlich, N.; Palatinszky, M.; Vierheilig, J.; Bulaev, A. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 2015, 528, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. Interaction between microplastic biofilm formation and antibiotics: Effect of microplastic biofilm and its driving mechanisms on antibiotic resistance gene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakoula, D.; Koch, H.; Frank, J.; Jetten, M.S.; van Kessel, M.A.; Lücker, S. Enrichment and physiological characterization of a novel comammox Nitrospira indicates ammonium inhibition of complete nitrification. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1010–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Peng, Y. Enrichment of comammox bacteria in anammox-dominated low-strength wastewater treatment system within microaerobic conditions: Cooperative effect driving enhanced nitrogen removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, H.; van Kessel, M.A.; Lücker, S. Complete nitrification: Insights into the ecophysiology of comammox Nitrospira. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottshall, E.Y.; Bryson, S.J.; Cogert, K.I.; Landreau, M.; Sedlacek, C.J.; Stahl, D.A.; Daims, H.; Winkler, M. Sustained nitrogen loss in a symbiotic association of Comammox Nitrospira and Anammox bacteria. Water Res. 2021, 202, 117426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roots, P.; Wang, Y.; Rosenthal, A.F.; Griffin, J.S.; Sabba, F.; Petrovich, M.; Yang, F.; Kozak, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Wells, G.F. Comammox Nitrospira are the dominant ammonia oxidizers in a mainstream low dissolved oxygen nitrification reactor. Water Res. 2019, 157, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilardi, K.; Cotto, I.; Bachmann, M.; Parsons, M.; Klaus, S.; Wilson, C.; Bott, C.B.; Pieper, K.J.; Pinto, A.J. Co-occurrence and cooperation between comammox and anammox bacteria in a full-scale attached growth municipal wastewater treatment process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5013–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Chai, W.; Xiao, R.; Wang, B.; Lu, H. Synergy between comammox and anammox bacteria in wastewater ammonia removal. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 3, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Xiong, S.; Huang, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, S.; Guo, L.; Cui, J. Rates and causes of black soil erosion in Northeast China. Catena 2022, 214, 106250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Dang, J.; Li, P.; Yang, X.; Xiao, K.; Wang, K.; Duan, P.; Li, D. Afforestation-driven microbial nitrogen limitation promotes soil nitrous oxide production by ammonia oxidizers. Plant Soil 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hua, Z.-S.; Liu, T.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Bai, G.; Lücker, S.; Jetten, M.S.; Zheng, M.; Guo, J. Selective enrichment and metagenomic analysis of three novel comammox Nitrospira in a urine-fed membrane bioreactor. ISME Commun. 2021, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kits, K.D.; Jung, M.-Y.; Vierheilig, J.; Pjevac, P.; Sedlacek, C.J.; Liu, S.; Herbold, C.; Stein, L.Y.; Richter, A.; Wissel, H.; et al. Low yield and abiotic origin of N2O formed by the complete nitrifier Nitrospira inopinata. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, W.; Liu, G. Enhancing the relative abundance of comammox nitrospira in ammonia oxidizer community decreases N2O emission in nitrification exponentially. Chemosphere 2024, 356, 141883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.-H.; Wu, J.-H.; Chen, H.-W. Comammox Nitrospira cooperate with anammox bacteria in a partial nitritation–anammox membrane bioreactor treating low-strength ammonium wastewater at high loadings. Water Res. 2024, 257, 121698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kits, K.D.; Sedlacek, C.J.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Han, P.; Bulaev, A.; Pjevac, P.; Daebeler, A.; Romano, S.; Albertsen, M.; Stein, L.Y. Kinetic analysis of a complete nitrifier reveals an oligotrophic lifestyle. Nature 2017, 549, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yuan, G.; Song, Z.; Li, Q.; Liu, C.; Xu, A.; Luan, Y.; Liu, Y. In Situ Biofilm Aquaculture Systems (In Situ BFSs) for Litopenaeus vannamei: A Review. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Hu, J.; Jia, Z.; Hu, B. Biofilm: A strategy for the dominance of comammox Nitrospira. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.; Vilardi, K.; Cotto, I.; Sudarshan, A.; Bian, K.; Klaus, S.; Bachmann, M.; Parsons, M.; Wilson, C.; Bott, C. Metatranscriptomic analysis reveals synergistic activities of comammox and anammox bacteria in full-scale attached growth nitrogen removal system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13023–13034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson, S.; de Blois, M.; Wilén, B.-M.; Gustavsson, D. Treatment of municipal wastewater with aerobic granular sludge. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 48, 119–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotto, I.; Vilardi, K.J.; Huo, L.; Fogarty, E.C.; Khunjar, W.; Wilson, C.; De Clippeleir, H.; Gilmore, K.; Bailey, E.; Lücker, S. Low diversity and microdiversity of comammox bacteria in wastewater systems suggest specific adaptations within the Ca. Nitrospira nitrosa cluster. Water Res. 2023, 229, 119497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Fang, F.; Liu, G. Efficient nitrification and low-level N2O emission in a weakly acidic bioreactor at low dissolved-oxygen levels are due to comammox. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00154-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, B.; Kuenen, J.v.; Van Loosdrecht, M. Sewage treatment with anammox. Science 2010, 328, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lv, H.; Cui, B.; Zhou, D. NO-driven Anammox systems contribute to nitrogen removal via altering nitrogen transformation pathways and microbial interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 167030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, P.L. What is the best biological process for nitrogen removal: When and why? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3835–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, S.; Gilbert, E.M.; Vlaeminck, S.E.; Joss, A.; Horn, H.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C. Full-scale partial nitritation/anammox experiences–an application survey. Water Res. 2014, 55, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, K.; He, B.; Liu, R.; Qian, L.; Wan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, H.; Gong, H. Spontaneous mainstream anammox in a full-scale wastewater treatment plant with hybrid sludge retention time in a temperate zone of China. Water Environ. Res. 2021, 93, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.R.; Ali, M.; Katuri, K.P.; Gralnick, J.A.; Reimann, J.; Mesman, R.; van Niftrik, L.; Jetten, M.S.; Saikaly, P.E. Extracellular electron transfer-dependent anaerobic oxidation of ammonium by anammox bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, A. Exerting applied voltage promotes microbial activity of marine anammox bacteria for nitrogen removal in saline wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xing, L.; Zhang, H.; Gui, C.; Jin, S.; Lin, H.; Li, Q.; Cheng, C. Key factors to enhance soil remediation by bioelectrochemical systems (BESs): A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 419, 129600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kessel, M.A.; Speth, D.R.; Albertsen, M.; Nielsen, P.H.; Op den Camp, H.J.; Kartal, B.; Jetten, M.S.; Lücker, S. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 2015, 528, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagum, A. Integrated electro-anammox process for nitrogen removal from wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 13061–13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, G.; Sivakumar, M.; Wu, J. Enhancing integrated denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation and Anammox processes for nitrogen and methane removal: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 390–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to Fe (III) reduction: Discovery, mechanism and application prospects in wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhao, W. A novel iron-mediated nitrogen removal technology of ammonium oxidation coupled to nitrate/nitrite reduction: Recent advances. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Ai, Z.; Huang, W.; Yang, F.; Liu, F.; Lei, Z.; Huang, W. Recent progress in applications of Feammox technology for nitrogen removal from wastewaters: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 362, 127868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Huan, W.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J. Effects of straw incorporation and potassium fertilizer on crop yields, soil organic carbon, and active carbon in the rice–wheat system. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Godfrey, B.J.; RedCorn, R.; Wang, Z.; Goel, R.; Winkler, M.-K. Simultaneous anaerobic carbon and nitrogen removal from primary municipal wastewater with hydrogel encapsulated anaerobic digestion sludge and AOA-anammox coated hollow fiber membrane. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Godfrey, B.J.; RedCorn, R.; Candry, P.; Abrahamson, B.; Wang, Z.; Goel, R.; Winkler, M.-K. Mainstream nitrogen removal from low temperature and low ammonium strength municipal wastewater using hydrogel-encapsulated comammox and anammox. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.-Q.; Xie, G.-J.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Z.-C.; Liu, B.-F.; Xing, D.-F.; Ding, J.; Han, H.-J.; Ren, N.-Q. Mainstream nitrogen and dissolved methane removal through coupling n-DAMO with anammox in granular sludge at low temperature. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16586–16596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Q.; Huang, S.; Zhang, N. Enhancing nitrogen removal efficiency and anammox metabolism in microbial electrolysis cell coupled anammox through different voltage application. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, M.; Gu, X.; Yan, P.; He, S.; Chachar, A. New insight and enhancement mechanisms for Feammox process by electron shuttles in wastewater treatment—A systematic review. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuri, K.P.; Ali, M.; Saikaly, P.E. The role of microbial electrolysis cell in urban wastewater treatment: Integration options, challenges, and prospects. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshi, C.; Hong, K.B.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jianzhong, H.; Chye, C.S.; Long, W.Y.; Ghani, Y. Mainstream partial nitritation/anammox nitrogen removal process in the largest water reclamation plant in Singapore. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2015, 41, 1441–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; He, D.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Q.; Ma, X.; Ma, J.; Zheng, M. Dual sludge system driven NDFO-Feammox coupling: Optimization of the iron cycling network for sustainable and efficient nitrogen removal. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pan, W.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Y. Deciphering iron interactions with anaerobic ammonia oxidation: Nitrogen removal performance, iron transformation, and microbial community characterization analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Jaffé, P.R. Isolation and characterization of an ammonium-oxidizing iron reducer: Acidimicrobiaceae sp. A6. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valk, L.C.; Peces, M.; Singleton, C.M.; Laursen, M.D.; Andersen, M.H.; Mielczarek, A.T.; Nielsen, P.H. Exploring the microbial influence on seasonal nitrous oxide concentration in a full-scale wastewater treatment plant using metagenome assembled genomes. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, D.; Woliy, K.; Degefu, T.; Frostegård, Å. A common mechanism for efficient N2O reduction in diverse isolates of nodule-forming bradyrhizobia. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, K.; Suenaga, T.; Kuroiwa, M.; Riya, S.; Terada, A. Exploring the functions of efficient canonical denitrifying bacteria as N2O sinks: Implications from 15N tracer and transcriptome analyses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 11694–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Zhou, Y.; Suenaga, T.; Oba, K.; Lu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Yoon, S.; Terada, A. Organic carbon determines nitrous oxide consumption activity of clade I and II nosZ bacteria: Genomic and biokinetic insights. Water Res. 2022, 209, 117910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onley, J.R.; Ahsan, S.; Sanford, R.A.; Löffler, F.E. Denitrification by Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans, a common soil bacterium lacking the nitrite reductase genes nirS and nirK. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01985-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaSarre, B.; Morlen, R.; Neumann, G.C.; Harwood, C.S.; McKinlay, J.B. Nitrous oxide reduction by two partial denitrifying bacteria requires denitrification intermediates that cannot be respired. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e01741-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Kim, H.; Yoon, S. Nitrous oxide reduction by an obligate aerobic bacterium, Gemmatimonas aurantiaca strain T-27. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00502–e00517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.D.; Han, H.; Yun, T.; Song, M.J.; Terada, A.; Laureni, M.; Yoon, S. Identification of nosZ-expressing microorganisms consuming trace N2O in microaerobic chemostat consortia dominated by an uncultured Burkholderiales. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Vishwanathan, N.; Kowaliczko, S.; Ishii, S. Clarifying microbial nitrous oxide reduction under aerobic conditions: Tolerant, intolerant, and sensitive. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04709–e04722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Song, M.J.; Yoon, S. Design and feasibility analysis of a self-sustaining biofiltration system for removal of low concentration N2O emitted from wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10736–10745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, D.D.; Song, M.J.; Yun, T.; Yoon, H.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, Y.M.; Laureni, M.; Yoon, S. Biotrickling filtration for the reduction of N2O emitted during wastewater treatment: Results from a long-term in situ pilot-scale testing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3883–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parravicini, V.; Nielsen, P.H.; Thornberg, D.; Pistocchi, A. Evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions from the European urban wastewater sector, and options for their reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomowski, A.; Zumft, W.G.; Kroneck, P.M.; Einsle, O. N2O binding at a [4Cu:2S] copper–sulphur cluster in nitrous oxide reductase. Nature 2011, 477, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suenaga, T.; Aoyagi, R.; Sakamoto, N.; Riya, S.; Ohashi, H.; Hosomi, M.; Tokuyama, H.; Terada, A. Immobilization of Azospira sp. strain I13 by gel entrapment for mitigation of N2O from biological wastewater treatment plants: Biokinetic characterization and modeling. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 126, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suenaga, T.; Riya, S.; Hosomi, M.; Terada, A. Biokinetic characterization and activities of N2O-reducing bacteria in response to various oxygen levels. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinh, C.T.; Suenaga, T.; Hori, T.; Riya, S.; Hosomi, M.; Smets, B.F.; Terada, A. Counter-diffusion biofilms have lower N2O emissions than co-diffusion biofilms during simultaneous nitrification and denitrification: Insights from depth-profile analysis. Water Res. 2017, 124, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uri-Carreño, N.; Nielsen, P.H.; Gernaey, K.V.; Domingo-Félez, C.; Flores-Alsina, X. Nitrous oxide emissions from two full-scale membrane-aerated biofilm reactors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherson, Y.D.; Wells, G.F.; Woo, S.-G.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Cantwell, B.J.; Criddle, C.S. Nitrogen removal with energy recovery through N2O decomposition. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, X.-F.; Yu, Y.-Q.; Liu, X.; Zeng, R.J.-X.; Zhou, S.-G.; He, Z. Light-driven nitrous oxide production via autotrophic denitrification by self-photosensitized Thiobacillus denitrificans. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisova, K.; Ilyin, A.; Rumyantsev, R.; Ilyin, A.; Volkova, A. Nitrous oxide: Production, application, and protection of the environment. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2019, 89, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Lian, X.; Liu, S.; Wu, G.; Xu, J.; Li, L. Efficient nitrous oxide capture by cationic forms of FAU and CHA zeolites. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462, 142300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Koch, K.; Wells, G.F.; Weißbach, M.; Yuan, Z.; Ye, L. Recovery of nitrous oxide from wastewater treatment: Current status and perspectives. ACS EST Water 2020, 1, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampschreur, M.J.; Temmink, H.; Kleerebezem, R.; Jetten, M.S.; van Loosdrecht, M.C. Nitrous oxide emission during wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2009, 43, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Oshiki, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Satoh, H. N2O emission from a partial nitrification–anammox process and identification of a key biological process of N2O emission from anammox granules. Water Res. 2011, 45, 6461–6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, O.D.; Quijano, G.; Pérez, R.; Munoz, R. Simultaneous biological nitrous oxide abatement and wastewater treatment in a denitrifying off-gas bioscrubber. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 288, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, L.S.; Nerenberg, R. Total nitrogen removal in a hybrid, membrane-aerated activated sludge process. Water Res. 2008, 42, 3697–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, L.S.; Nerenberg, R. Sustainable nitrogen removal from wastewater with the hybrid membrane biofilm process (HMBP): Bench-scale studies. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 58, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, L.; Ye, W.; Zhao, B.; Peng, Y.; Liu, G.; Gao, X.; Peng, X. Simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in a hybrid activated sludge-membrane aerated biofilm reactor (H-MABR) for nitrogen removal from low COD/N interflow: A pilot-scale study. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 122038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherson, Y.D.; Roa, A.; Darling, G.; Criddle, C.S. Sidestream Treatment with Energy Recovery from Nitrogen Waste: The Coupled Aerobic-anoxic Nitrous Decomposition Operation (CANDO). In Proceedings of the WEFTEC 2014, 87th Annual Technical Exhibition & Conference, Water Environment Federation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 September–1 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scherson, Y.D. Energy Recovery from Waste Nitrogen Through N2O Decomposition: The Coupled Aerobic-Anoxic Nitrous Decomposition Operation (CANDO). Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Alejo, C.J.; Khambhati, Y.K.; Papadopoulos, A.; Reli, M.; Ricka, R. Using photocatalysis for sustainable agriculture: R-leaf’s potential in large-scale N2O mitigation. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissel, V.; Tahir, S.; Koh, C.A. Catalytic decomposition of N2O over monolithic supported noble metal-transition metal oxides. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2006, 64, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suenaga, T.; Hori, T.; Riya, S.; Hosomi, M.; Smets, B.F.; Terada, A. Enrichment, isolation, and characterization of high-affinity N2O-reducing bacteria in a gas-permeable membrane reactor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12101–12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, K.; Suenaga, T.; Yasuda, S.; Kuroiwa, M.; Hori, T.; Lackner, S.; Terada, A. Quest for nitrous oxide-reducing bacteria present in an anammox biofilm fed with nitrous oxide. Microbes Environ. 2024, 39, ME23106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bothin Hanssen, H. Practical Control Strategies for Reducing N2O Emissions in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hiis, E.G.; Vick, S.H.; Molstad, L.; Røsdal, K.; Jonassen, K.R.; Winiwarter, W.; Bakken, L.R. Unlocking bacterial potential to reduce farmland N2O emissions. Nature 2024, 630, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Yang, X. Linking N2O emissions and nos Z gene abundance: A meta-analysis of organic carbon amendments in agricultural soils. Plant Soil 2025, 448, 180–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Li, X.; Li, X. Toward energy neutrality in municipal wastewater treatment: A systematic analysis of energy flow balance for different scenarios. Acs EsT Water 2021, 1, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamawand, I. Energy consumption in water/wastewater treatment industry—Optimisation potentials. Energies 2023, 16, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process | Operating DO (mg L−1) | Temperature Window (°C) | C/N Requirement | Main Bottleneck | Demonstrated Scale | Typical N-Removal Rate (kg N m−3 d−1) | Typical N2O Factor (% of Influent N) | Indicative Energy Cost (kWh kg−1 N Removed) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainstream PN/A | 0.15–0.5 | 10–30 | Low (autotrophic) | NOB suppression; low-T activity of anammox | Pilot to full | 0.05–0.25 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.2–0.4 | [45,46] |

| Comammox–anammox | 0.05–0.3 | 10–30 | Low (autotrophic) | Slow comammox growth; coexistence balance | Lab to pilot | 0.02–0.15 | ≤0.3 | 0.3–0.5 | [27,47,51] |

| Electro-anammox | 0 (anoxic cathode) | 15–35 | None (autotrophic, electrons via anode) | Electrode stability; biofilm conductivity | Lab | 0.05–0.20 | <0.1 | 0.1–0.3 | [52,53] |

| Feammox | 0 (strict anaerobic) | 20–40 | None (autotrophic) | Low rate; Fe(III) supply; microbial uncertainty | Lab | 0.001–0.01 | Not reported | ≈0 (exothermic, no aeration) | [54,55,56] |

| Technology | Mechanism | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | Key Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilter off-gas polishing | Biological oxidation of N2O in exhaust gas via nitrifying/denitrifying biofilms | 7–8 (pilot to full) | Requires gas capture; sensitive to humidity and NO2−/O2 ratios | [90,91,92] |

| MABR (Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor) | Stratified O2 delivery through membranes forming aerobic-anoxic gradients, reducing N2O intermediates | 7 (pilot to full) | Membrane fouling: control of DO flux; capital cost | [93,94,95] |

| CANDO/CANDO+ (Coupled Aerobic-Anoxic Nitrous Decomposition and Recovery) | Two-stage process: biological NO2− → N2O generation and subsequent thermal or catalytic conversion to N2 with energy recovery | 6–7 (pilot) | Control of NO2− accumulation; N2O capture and storage logistics | [96,97] |

| Catalytic/Photocatalytic N2O reduction | Abiotic conversion of N2O to N2 using metal or light-activated catalysts | 3–4 (lab) | Catalyst deactivation; energy input requirement | [98,99] |

| Biotic N2O sink bioaugmentation | Enrichment of high-affinity N2O-reducing bacteria for in situ reduction of N2O to N2 | 4–6 (lab to pilot) | Maintaining active populations; substrate competition | [100,101,102] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaaban, M.; Zhou, K.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Wu, L.; Younas, A.; Wu, Y. Advancements in Microbial Nitrogen Pathways for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Water 2025, 17, 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233409

Shaaban M, Zhou K, Asgari Lajayer B, Wu L, Younas A, Wu Y. Advancements in Microbial Nitrogen Pathways for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Water. 2025; 17(23):3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233409

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaaban, Muhammad, Kaiyan Zhou, Behnam Asgari Lajayer, Lei Wu, Aneela Younas, and Yupeng Wu. 2025. "Advancements in Microbial Nitrogen Pathways for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment" Water 17, no. 23: 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233409

APA StyleShaaban, M., Zhou, K., Asgari Lajayer, B., Wu, L., Younas, A., & Wu, Y. (2025). Advancements in Microbial Nitrogen Pathways for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Water, 17(23), 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233409