Microbial Response of Fe and Mn Biogeochemical Processes in Hyporheic Zone Affected by Groundwater Exploitation Along Riverbank

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

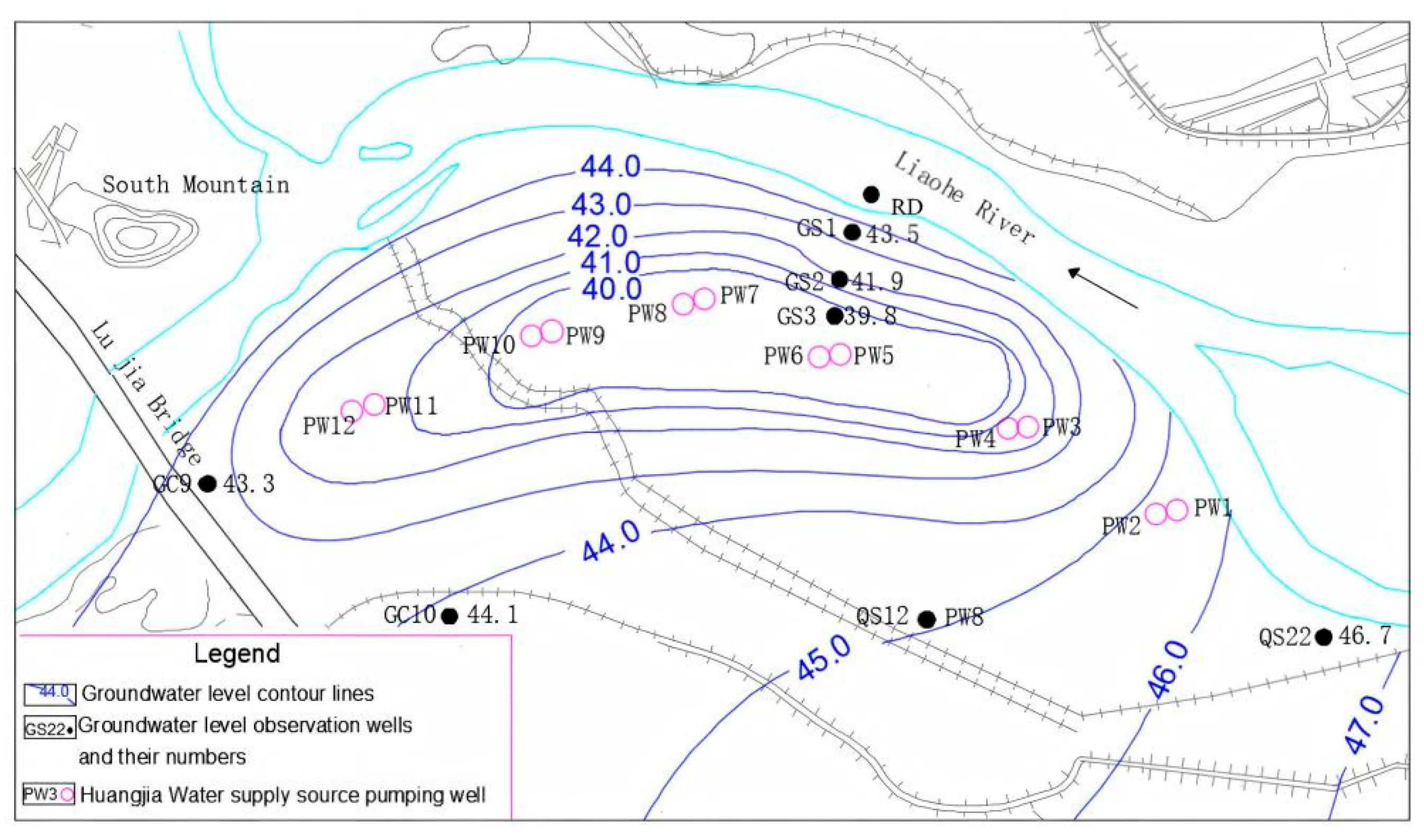

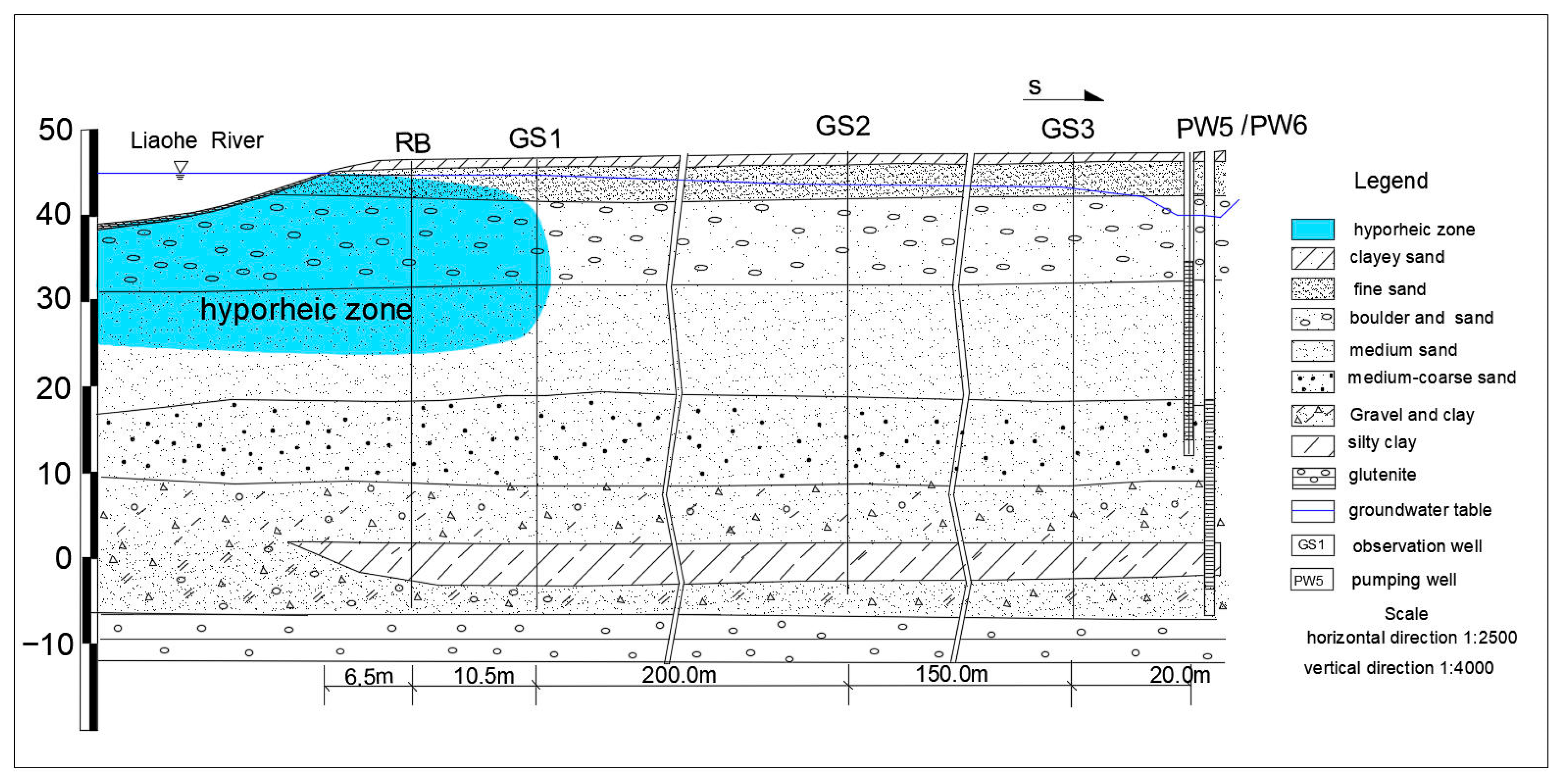

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.1.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.1.2. Sampling of Riverbed Sediments and Hyporheic Zones of Aquatic Media

2.1.3. Collection of Microbiological Samples from River Water and Groundwater

2.2. Determination of Microbial Community Structure

3. Results and Analysis

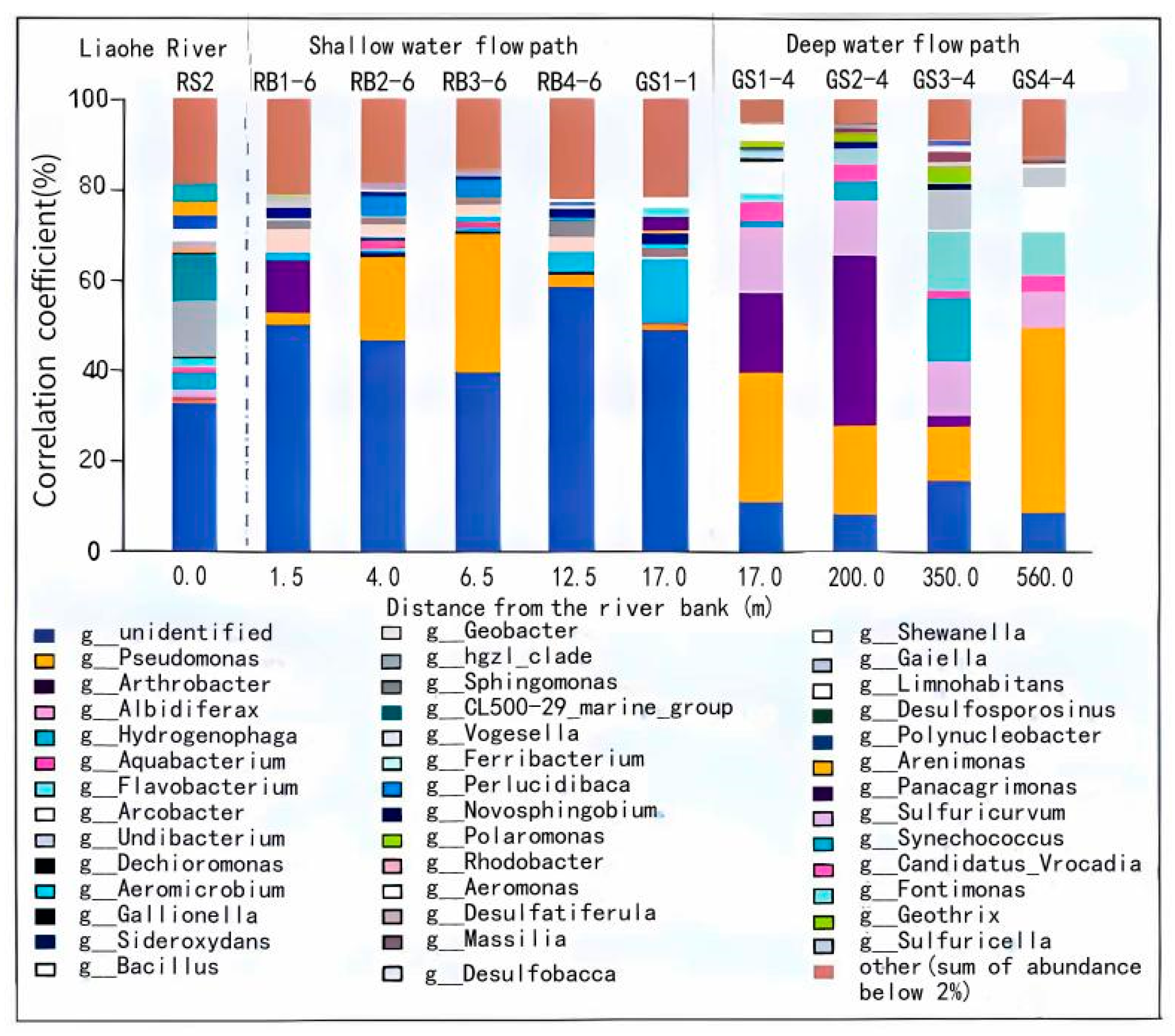

3.1. Microbial Species Composition in Riverbed Sediments and Aquatic Media

- (1)

- Alphaproteobacteria

- (2)

- Betaproteobacteria

- (3)

- Gammaproteobacteria

- (4)

- Deltaproteobacteria

- (5)

- Epsilonproteobacteria

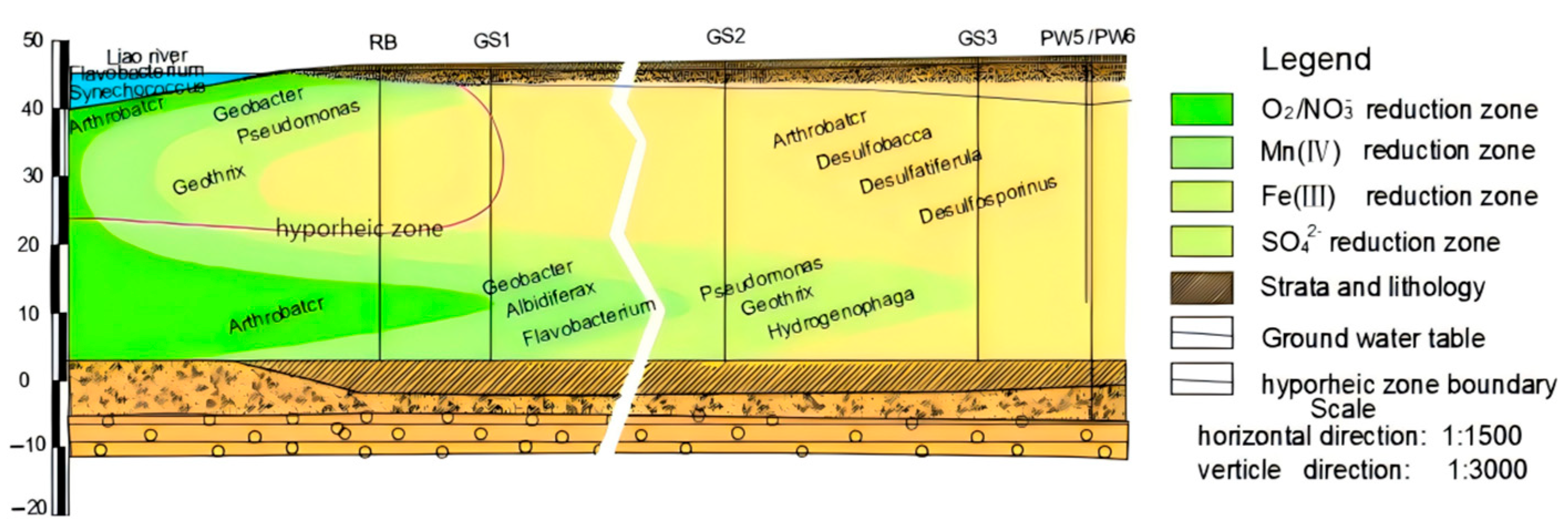

3.2. Characterization of Microbial Response to Redox Subzone in Hyporheic Zones

3.2.1. Characterization of Spatial Distribution of Microbial Communities in Riverbed Sediments and Hyporheic Zones

- (1)

- Distribution characteristics of microbial dominant bacteria in riverbed sediments

- (2)

- Characterization of the spatial distribution of microbial communities in the hyporheic zone

3.2.2. Characterization of the Synergistic Evolution of Microorganisms and Groundwater Hydrochemistry in Aqueous Media

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, X.Y.; Huang, X.Y.; Fan, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, Q.; Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Characteristics and influencing factors of microbial communities in the typical riparian hyporheic zone of Rare Earth Mining Area. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.W.; Wagner, B.J.; Bencala, K.E. Evaluating the reliability of the stream tracer approach to characterize stream-sub-surface water exchange. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boano, F.; Harvey, J.W.; Marion, A.; Pack-man, A.I.; Revelli, R.; Ridolfi, L.; Wörman, A. Hyporheic flow and transport processes: Mechanisms, models, and biogeochemical implications. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 603–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, T.; Najman, J.; Nowobilska-Luberda, A.; Bergel, T.; Kaczor, G. Analysis of the interaction between surface water and groundwater using gaseous tracers in a dynamic test at a riverbank filtration intake. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Wu, H.; Li, L.; Newcomer, D.; Long, P.E.; Williams, K.H. Uranium bioreduction rates across scales: Biogeochemical hot moments and hot spots during a biostimulation experiment at rifle, Colorado. Environmental Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 10116–10127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shang, J.; Kerisit, S.; Zachara, J.M.; Zhu, W. Scale-dependent rates of uranyl surface complexation reaction in sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 105, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sanford, A.R.; Bethke, C.M. Microbial activity and chemical weathering in the Middendorf aquifer, South Carolina. Chem. Geol. 2009, 258, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Koh, D.-C.; Park, S.-J.; Cha, I.-T.; Park, J.-W.; Na, J.-H.; Roh, Y.; Ko, K.-S.; Kim, K.; Rhee, S.-K. Molecular Analysis of Spatial Variation of Iron-Reducing Bacteria in Riverine Alluvial Aquifers of the Mankyeong River. J. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medihala, P.G.; Lawrence, J.R.; Swerhone, G.D.W.; Korber, D.R. Spatial Variation in Microbial Community Structure, Richness, and Diversity in an Alluvial Aquifer. Can. J. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivetta, M.R.S.; Buss, E.A. Nitrate Attenuation in Groundwater: A Review of Biogeochemical Controlling Processes. Water Res. 2008, 42, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.W.; Fuller, C.C. Effect of Enhanced Manganese Oxidation in the Hyporheic Zone on Basin-scale Geochemical Mass Balance. Water Resour. Res. 1998, 34, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, L.J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Study on evolution characteristics of groundwater system in a deep mining area in western China based on Feflow software. Miner. Resour. Prot. Util. 2025, 45, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Q.; Zhang, S.X.; Hu, C.; Huang, L. Open Experiment in Environmental Chemistry: Passivation of Heavy Metal Cd in Cultivated Soils. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 2025, 53, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. Study on the Migration and Transformation Processes of Iron and Manganese in the River Water Infiltration Zone Under the Influence of Riverbed Scouring and Silting; Jilin University: Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Gui, H.R.; Guo, Y.; Li, J. Characteristics of deep groundwater microbial communities in Huaibei Coalfield and their significance for water source tracing. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 3503–3512. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.F.; Zhi, C.S.; Hu, X.N.; Huang, X.R.; Chen, G. Effects of seawater (saline water) intrusion on microbial community structure in the aquifer of southern Laizhou Bay. J. Univ. Jinan 2025, 39, 38–45+62. [Google Scholar]

- de Paula, M., Jr.; da Costa, T.A.; Silva Soriano, A.A.B.; Lacorte, G.A. Spatial distribution of sediment bacterial communities from São Francisco River headwaters is influenced by human land-use activities and seasonal climate shifts. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 3005–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.P.; Wang, B.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, S.-J. Novosphingobium taihuense sp nov., a novel aromatic-compound-degrading bacterium isolated from Taihu Lake, China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1229–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.G. Analysis of Functional Microorganisms and Community Dynamics for Nitrogen Removal from Aerobic Granular Sludge; Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, China, 2007; Available online: https://www.cnki.net/ (accessed on 1 July 2007).

- Sohn, J.H.; Kwon, K.K.; Kang, J.-H.; Jung, H.-B.; Kim, S.-J. Novosphingobium pentaromativorans sp. Nov. a High-molecular-mass Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-degrading Bacterium Isolated from Estuarine Sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1483–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.Y.; Li, J.; Chen, R.P.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.Z.; Zhang, Z.N.; Klotz, M.G. Diversity, Abundance, and Spatial Distribution of Sediment Ammonia-oxidizing Betaproteobacteria in Response to Environmental Gradients and Coastal Eutrophication in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 4691–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laanbroek, H.J.; Keijzer, R.M.; Verhoeven, J.T.A.; Whigham, D.F. The Distribution of Ammonia-oxidizing Betaproteobacteria in Stands of Black Mangroves (Avicennia Germinans). Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Characteristics of the Denitrifying Phosphate-accumulating Organisms and Synchronization Mechanism of Denitrification and Phosphorus Removal; Wuhan University: Wuhan, China, 2011; Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1167.P.20220621.1012.004.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Vatsurina, A.; Badrutdinova, D.; Schumann, P.; Spring, S.; Vainshtein, M. Desulfosporosinus Hippel sp. Nov. a Mesophilic Sulfate-reducing Bacterium Isolated from Permafrost. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenik, B.; Brahamsha, B.; Larimer, F.W.; Land, M.; Hauser, L.; Chain, P.; Lamerdin, J.; Regala, W.; Allen, E.E.; McCarren, J.; et al. The Genome of a Motile Marine Synechococcus. Nature 2003, 424, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, B.; Kuenen, G.J.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Sewage Treatment with Anammox. Sci. China 2010, 328, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Hunnicutt, D.W.; McBride, M.J. Cloning and Characterization of the Flavobacterium Johnsoniae (Cytophaga Johnsonae) Gliding Motility Gene, gldA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12139–12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Bernad, I.; Anderson, R.T.; Vrionis, H.A.; Lovley, D.R. Vanadium Respiration by Geobacter Metallireducens: Novel Strategy for in Situ Removal of Vanadium from Groundwater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 3091–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Infiltration Path | Redox Subzone | Dominant Bacterium | Functionality | Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riverbed | Aerobic zone | Flavobacterium Synechococcus | In the presence of Mn2+, it can activate intracellular enzymes to promote the degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Flavobacterium, which is mainly used in the environment for the degradation of phenol, phenanthrene, naphthalene, and other aromatic compounds [25]. | 18.24% |

| Shallow flow infiltration paths | O2/NO3−-reducing zone | Arthrobacter | Participation in denitrification in the degradation of organic matter [26]. | 11.26% |

| Mn(IV)-reducing zone | Geobacter | Degradation of organic pollutants using Fe(III), MnO4, and AsO3− as electron acceptors. | 15.91% | |

| Fe(III)-reducing zone | Pseudomonas Geothrix | Efficient degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), participation in denitrification, and exchange of Fe with Al/Ca cations in phosphates, in conjunction with competitive adsorption of phosphates affecting As release and immobilization [23]. | 27.28% | |

| Sulfate-reducing zone | Arcobacter Desulfobacca Desulfatiferula Desulfosporosinus | Sulfate and sulfur reduction [24]. | 13.41% | |

| Deep water infiltration paths | O2/NO3−-reducing zone | Arthrobacter | Participation in denitrification in the degradation of organic matter [26]. | 17.69% |

| Mn(IV)-reducing zone | Geobacter Albidiferax Flavobacterium | Degradation of organic pollutants using Fe(III), MnO4, and AsO3− as electron acceptors, typical of iron-reducing bacteria, reducing iron and most arsenite and chemically converting manganese to other forms of oxides. | 12.91% | |

| Fe(III)-reducing zone | Pseudomonas Geothrix Hydrogenophaga | Efficient degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), participation in denitrification, and exchange of Fe with Al/Ca cations in phosphates, in conjunction with competitive adsorption of phosphates affecting As release and immobilization [23]. | 14.07% | |

| Sulfate-reducing zone | Arcobacter Desulfobacca Desulfatiferula Desulfosporosinus | Sulfate and sulfur reduction [24]. | 12.23% |

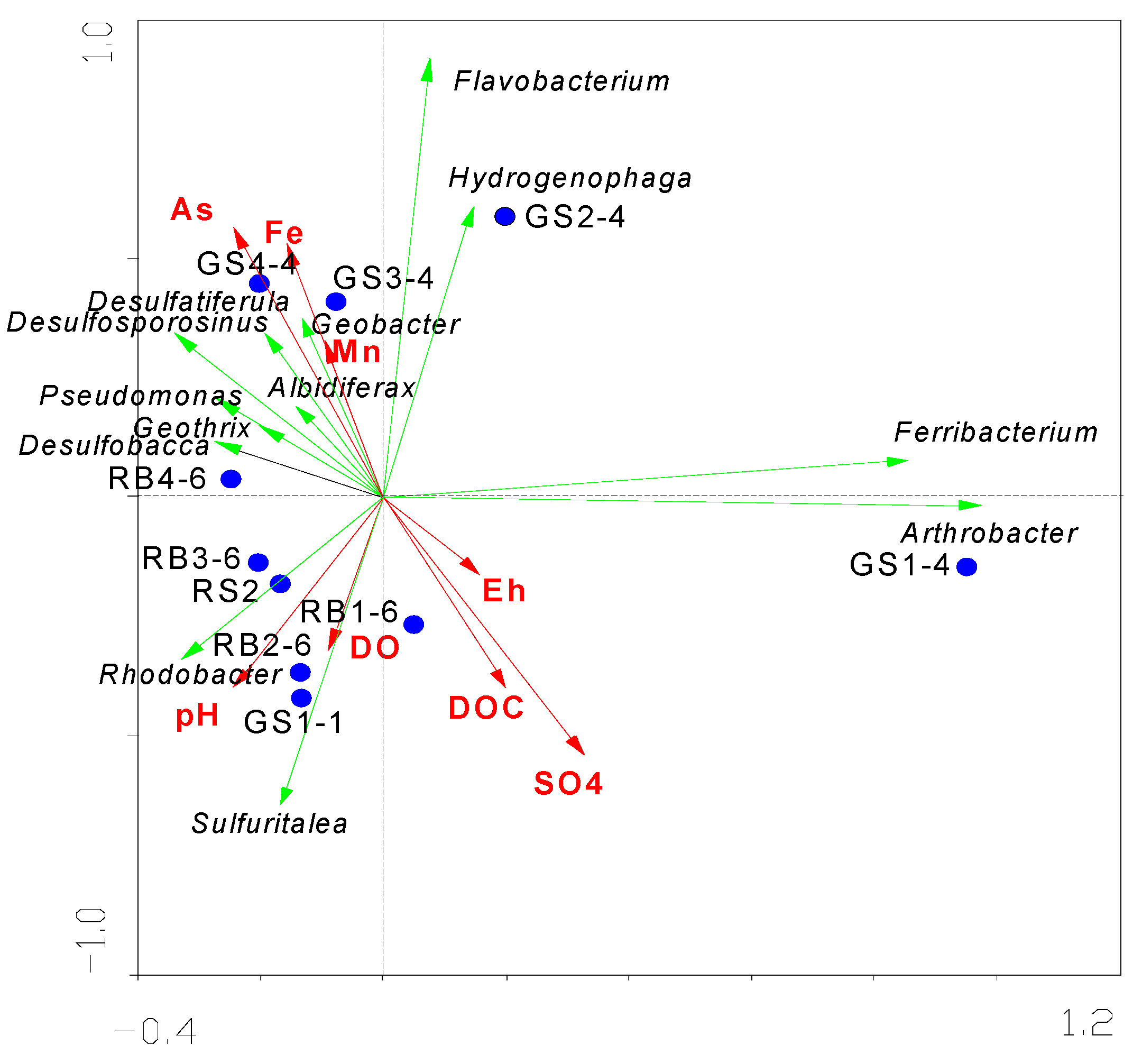

| Parameters | Axis I | Axis II |

|---|---|---|

| DOC (mg/L) | 0.1936 | −0.3633 |

| pH | −0.2480 | −0.3636 |

| DO (mg/L) | −0.0909 | −0.2840 |

| Mn2− (mg/L) | −0.0984 | 0.2950 |

| SO42− (mg/L) | 0.3190 | −0.4916 |

| Fe2+ (mg/kg) | −0.1560 | 0.4831 |

| Eh (mV) | 0.1544 | −0.1462 |

| As (ng/L) | −0.2404 | 0.5177 |

| Eigenvalues | 0.894 | 0.080 |

| Species environment correlations | 0.995 | 0.921 |

| * CPV of species data | 89.4 | 97.5 |

| * CPV of species environment relation | 91.6 | 94.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Pan, J. Microbial Response of Fe and Mn Biogeochemical Processes in Hyporheic Zone Affected by Groundwater Exploitation Along Riverbank. Water 2025, 17, 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233408

Wang Y, Pan J. Microbial Response of Fe and Mn Biogeochemical Processes in Hyporheic Zone Affected by Groundwater Exploitation Along Riverbank. Water. 2025; 17(23):3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233408

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yijin, and Jun Pan. 2025. "Microbial Response of Fe and Mn Biogeochemical Processes in Hyporheic Zone Affected by Groundwater Exploitation Along Riverbank" Water 17, no. 23: 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233408

APA StyleWang, Y., & Pan, J. (2025). Microbial Response of Fe and Mn Biogeochemical Processes in Hyporheic Zone Affected by Groundwater Exploitation Along Riverbank. Water, 17(23), 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233408