1. Introduction

Coastal populations around the world are facing enormous environmental challenges from climate change, sea level rise, increasing storm frequency/intensity, coastal erosion, and so on [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The adaptations of coastal to communities to such stressors is therefore a key issue spanning environmental, economic, social, and political domains. The human–environmental interactions inherent to such adaptive strategies are also themselves a crucial factor influencing the manifestations of environmental problems. For the purposes of this paper, we can state rather axiomatically that fishing and other forms of marine resource extraction feature heavily in the adaptive frameworks of coastal communities as these shift through time and the effects of extractive activities are inevitably constrained by fishing regulations. In such a context, fishing regulations, in governing marine resource allocation, are at least theoretically designed to maximize economic production while minimizing negative environmental impacts and “tragedy of the commons” issues [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Fishing regulations inherently structure both socioeconomic and environmental systems in coastal contexts [

11]. Parametric regulations—i.e., those that restrict the methods, locations, and timing of fishing activities—obviously play a crucial role in determining the economic productivity of commercial fishing activities in general, and productivity of associated with particular contexts, seasons, technologies, tactics, and cultural traditions (etc.) specifically. Similarly, fishing regulations profoundly influence the ecosystemic conditions within and beyond the contexts that they govern, doing so in both intended and direct ways, as well as indirect and often unintended fashions.

Furthermore, fishing regulations exist within a wider political economy of state power in being determined by governmental processes of authority at a range of local, national, and international scales. As such, fisheries management is fundamentally political. This subjects the formulation of fisheries regulations to the same welding together of governmental political and industrial economic power involved in the resolution of other resource allocation problems—though fisheries managers often invoke scientific objectivity from the standpoints of both conservation and economic production to justify particular laws, regulations, and policies. This situation also positions fisheries regulations at the nexus of a range of issues having to do with inequality and spanning the domains of race, class, gender, cultural identity, and so on, as well as environmental justice, equity, and marginalization [

12,

13,

14].

From my perspective, at least, coastal communities are the eye of the needle for human populations facing the consequences of climate change. Coastal populations experience the full effects of sea level rise, which physically threatens communities, erodes coastlines, destroys delicate ecosystems, and degrades economically irreplaceable fisheries resources. They experience enormous flooding risk from storms, tropical and otherwise, and other phenomena that exacerbate sea level surges and marine water/wind energy. They are also often key locations of petrochemical energy production by virtue of their proximity to fossil fuel deposits (which tend to be located at continental margins), transport hubs, and shipping terminals. This relationship with oil and gas exposes coastal regions to an elevated risk of technological disaster, while ironically increasing the very same carbon emissions that threaten their existence from the standpoint of climate change.

Coastal fishing communities are also keystones in dealing with the ecological consequences of climate change. Though often cast as “ecological villains” by self-interested political constituencies [

15], fishing communities are the main human interface between ecological and socioeconomic systems. In the sense that their livelihoods depend on it, they are responsible for monitoring and maintaining countless interconnected features of the coastal landscapes and ecosystems on which fisheries rely. They are also deep repositories of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which is embedded within enduring cultural traditions and which acts as memory in terms of the adaptive experiences of countless generations of coastal ancestors [

16]. Small-scale fishers may be contrasted with large-scale industrial fishing, which often occurs side-by-side in the same waters and which does enormous ecological damage in extracting resources while concentrating wealth in the hands of distant economic elites. In my view, enhancing the stability, wellbeing, and resilience of small, rural coastal fishing communities is a humane, ethically virtuous, and environmentally effective collective strategy in confronting the challenges of climate change.

This paper examines ways in which fisheries regulations have served as an element of the broader political economy of policies and projects, which have undermined the existence of coastal communities in the coastal Lower Mississippi River Delta of Southeast Louisiana (

Figure 1). Located in Plaquemines Parish, a local governmental administrative unit of the state of Louisiana, this region has a long history of commercial fishing, particularly focused on shrimp (

Litopenaeus setiferus and

Farfantepenaeus aztecus) and oysters (

Crassostrea virginica), primarily harvested by small (family-scale) entrepreneurial vessel-owning fishers. Though commercial fishing has declined in recent decades for various reasons at stake in this paper, this region continues to have the highest levels of US commercial landings outside of Alaska. Next, Plaquemines Parish has a long history of oil and gas exploitation, beginning in the early 20th century and continuing today. Early in this history, parish- and state-level elites utilized their local political power to clear landholding fishing populations from the coastal marsh to make way for oil extraction, massively enriching themselves in the process [

17]. Finally, Plaquemines Parish has been a major hotspot of diversity, migration, and racial inequality. Its early history includes the Euro-American persecution of indigenous populations, the plantation era of chattel slavery, the “Jim Crow” era of 20th century racial segregation, and more recent hostility toward waves of Eastern European, Southeast Asian, and Latin American immigrants.

My analysis focuses on two major historical political–economic forces having to do with oil production and other industrial activities, which have affected the wellbeing of coastal communities through time in ways that may seem contradictory: (1) negative patterns of interaction in which coastal communities have been seen by industrial political–economic elites as impediments to oil and gas development and in which those elites have used their power to eliminate obstacles and opposition; (2) positive patterns of interaction in which economic opportunities within the oil and gas industry have supported economic systems among coastal communities based on commercial fishing, and in which coastal fishing communities have supported oil and gas production in providing experienced marine labor.

Both patterns intimately influence coastal fishing populations in myriad ways: socially, economically, ecologically, and even social–psychologically. This paper also shows the intimate connections between oil and gas industry production, small-scale commercial fishing activities, environmental conditions, fisheries health, and fishing regulations. While certain historical events, such as the 2010 B.P. oil spill, expose obvious and direct connections between these domains, this paper examines the breadth of subtler and often unrecognized intrinsic relationships. In this respect, this paper focuses much of its attention on the banning of gill nets in the 1990s, which was framed by its proponents as science-based and aimed toward environmentalist conservation goals [

15]. This paper examines the ways in which the gill net ban resulted from a complex combination of social, economic, environmental, and political pressures, many of which ultimately had to do with fluctuations in oil and gas industry production.

This paper examines the ways in which fishing regulations, whether intended or not, have articulated with a much longer historical political ecology of inequality characterized by land- and resource-use conflicts. The fact that such regulations have harmed small-scale commercial fishers in the region is unsurprising. Yet, I also show that they have had significant negative unintended consequences for local ecosystems and fisheries, which includes many counterproductive outcomes relative to the intent of those regulations by forcing fishing community members into problematic decisions.

As such, these dynamics naturally have profound structural consequences in terms the human–environmental interactions inherent to fishing community economies, including not only fisheries abundance but also broader coastal ecological wellbeing and resilience. Political ecology provides a useful theoretical position in the sense that fishing at its many scales becomes the site of conflict based on differences in terms of race, class, regional identity, and so on. Fishing regulations fundamentally occupy such a conflict space in representing negotiated outcomes ultimately based on power. This paper concludes by proposing some generalizable strategies for (1) regulating fisheries in politically fair, equitable, and sustainable ways, and (2) enhancing the wellbeing of coastal communities, ecosystems, and fisheries via supplement economic opportunities.

Methods: Triangulating Ethnographic and Historic/Archival Approaches

This study builds on a long-term program of participant observation ethnographic research in Lower Plaquemines Parish, which began in the spring of 2018 and is ongoing. One outcome of this research has been to expose the current constellation of conditions and problems facing coastal communities resulting from past events: hurricanes, oil spills, economic/industrial trends, political transitions, shifting regulatory frameworks and mechanisms, and so on. Thus, the key question facing any potential social scientific synthesis of coastal human–environmental interactions—as well as any attempts to improve policies and/or enhance fishing community wellbeing—is how did we get here? What historical events and processes were responsible for the coming into being of the current sets of conditions?

Of course, ethnographic methods are capable of speaking to the past. Fishing communities are deep repositories of memory in terms of past events, patterns of change through time, and the various forces that shape those patterns. Yet, on the one hand, such memories are not unanimous: individual memories are shaped by elements of personal context in both the past and present and thus reflect a wide range of identities and interests. This is especially true to the degree that discourse about the past is inevitably political precisely because of the relevance of historical context to ongoing tensions and conflicts. On the other hand, collective memory progressively fades as time elapses: community members move away, individuals age and pass away, contexts change, etc.

This paper utilizes ethnographic information gained through participant observation research to guide further historical/archival investigations. Such investigations focus primarily on two time periods: (1) the 1990s as the period in which gill net use was banned; (2) the early 21st century Era of Disasters as a period characterized by the impacts from and responses to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the 2010 B.P. oil spill, and other human-made and natural disasters. These time periods consistently arose as key turning points in terms of both the wellbeing of coastal communities in Lower Plaquemines Parish and the organization of small-scale fishing activities. My ethnographic findings effectively pointed the way to historical research in the investigation of informants’ claims and memories of past events and conditions, both exploring external evidence for such claims and exposing underexplored historical relationships.

In eight years of ethnographic research in the area, my colleagues and I have spent 133 nights in Lower Plaquemines Parish with stays ranging between 2 and 20 nights. We have also staged innumerable day trips from our nearby home-base of New Orleans. In our fieldwork, we have conducted 60+ formal interviews. Since 2021 (i.e., since COVID-19), we have also participated in 54 subsistence and/or small-scale commercial trips fishing trips—8 staged on commercial fishing vessels and 46 from the bank/shore. Such trips employed diverse gear including rod and reel, hoop nets, long lines, jug lines, and cast nets. In the context of such fishing trips, we undertook informal interviews with 44 different fishers—on multiple occasions with certain individuals. Finally, we have also had hundreds of small-scale interactions with community residents in our day-to-day activities and we have also had many online interactions with both individuals and social media groups, such as the “Plaquemines Parish Nosey Neighbors” Facebook group.

Our combined sample of formal interviews, informal interviews, and participant observation fishing trips (which overlapped heavily) included 29 white men, 3 white women, 10 black men, 3 black woman, 5 Vietnamese men, 2 Vietnamese women, 4 Latino men, and 1 Latina woman. We utilized “snowball sampling” as a non-probabilistic sampling technique mostly as a response to the difficulties in recruiting interview subjects [

18]. Early in the project, we were generally regarded with suspicion given both a long history of local mistreatment at the hands of outsiders (as I will describe further below) and contention over state-sponsored coastal restoration programs. In the summer of 2018, our lives were even threatened by oyster fishers who suspected that we were government agents involved in the planning of the locally unpopular Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion (MBSD) project [

19].

Though we have gained much trust in the community, it is clear that sampling biases and gaps remain. For example, the Vietnamese community holds an outsized role in the commercial fishing economy of Southeast Louisiana, yet we have encountered major difficulties in accessing this community based partly on issues of language but also suspicion of our motivations combined with strongly feelings of wanting to be left alone. Once, a first-generation Vietnamese immigrant with whom we have participated in a subsistence fishing trip explained that he and others believed that I was an agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) but that he regarded me as a friend nonetheless (even concluding our conversation about that with a gesture of giving me several pounds of fresh shrimp). While such a situation leaves much to be desired, we can claim perhaps the largest sample of ethnographic data collected for Lower Plaquemines Parish and certainly the largest number of fishing trips.

2. Coastal Fishing Communities in Lower Plaquemines Parish

Fishing has been the main form of economic production in the coastal Lower Mississippi River Delta since its geological formation. The Balize lobe of the Mississippi Delta is less than 1000 years old, likely resulting from a shift in river flow dynamics occurring during the most recent major period of global sea level drop associated with the Little Ice Age cold period [

20]. Human settlement of the region began immediately, with numerous indigenous mound villages dotting the surrounding coastal marsh (and with descendent indigenous communities still present in the area). Though early European colonial intrusions into the delta were limited by the complexity of the river’s anastomotic distributary channel network, the first French settlers arrived at the end of the 17th century. From this point, the area was heavily settled by European and Euro-American fishing communities taking advantage of the estuarine richness of the delta.

The commercial fishing industry evolved into its modern form through a series of technological transformations beginning in the late 19th century. At first, industrial technology related to shipping and canning led to the first larger-scale fishing activities across coastal Southeast Louisiana. Early canneries, such as the one located in the Plaquemines Parish ghost town of Ostrica, used industrial machinery, cheap immigrant labor, and monopolistic business tactics to take advantage of the Gulf Coast’s marine abundance in selling shellfish seafood.

Things changed in a more profound way with advances in refrigeration and vessel motor technology in the early-to-mid 20th century [

21]. Seafood could then be kept on ice aboard faster vessels powered by internal combustion engines, radically altering the ranges and targets of fishing vessels. Motorized vessels were also capable of deploying more effective capture technology, especially trawling nets and oyster dredges, over a wide area of the inshore coastal marsh.

In this context, landings surged across the middle of the 20th century, driven by a combination of these technological advances. From a social standpoint, such technologies allowed commercial seafood capture at the scale of house-level entrepreneurial vessel owners; and small-scale commercial fishers could use this combination of techniques and technologies to achieve economic self-sufficiency. This explains many of the socioeconomic and cultural features of coastal communities across Southeast Louisiana. If, as Marx [

22] once said, “The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist,” then the diesel-powered Lafitte skiff gives you the fishing society of coastal Southeast Louisiana.

While direct economic data is limited, older Lower Plaquemines Parish residents recall the period from the 1950s to the 1980s in highly favorable terms from the standpoint of commercial fishing. Older fishers universally remembered fisheries as much more abundant and far less regulated; and environmental conditions as less eroded, more vegetated (both terrestrially and aquatically), and less fragmented. Both my ethnographic data and historical data point to a key period of commercial fishing decline during the 1970s–1990s, which will be examined further below. This period was also followed by what I regard as the incipience of the current conditions characterized by disasters, disruption, environmental degradation, low seafood prices, and resulting declines in community wellbeing.

2.1. Historical Perspectives on the Oil and Gas Industry

In the past, many have pointed out the intertwining of the fates of small-scale commercial fishing and oil and gas industries in Plaquemines Parish, elsewhere across Southeast Louisiana, and beyond [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Both are at the core of modern coastal economic systems in the region, as well as the long-term dynamics of migration, cultural tradition, and sociopolitical stratification.

In the early 20th century, major oil deposits were discovered in marshes surrounding Plaquemines Parish. This brought tremendous change to the region, transforming what had been networks of small, rural fishing homesteads and villages into emerging centers of industrial fossil fuel production. In this process, longstanding dynamics of racial and class inequality were reworked politically through contention for land and oil resource access.

Up to that time, marginalized populations living in the remote coastal marshes of the delta had been tolerated by state-level political–economic elites. The land was effectively worthless, and elites were content to leave such populations alone as long as they were effectively out of sight. When it became apparent that the coastal marsh contained enormous mineral wealth, this attitude naturally changed suddenly. The early-to-mid 20th century was therefore rife with various forms of political conspiracy, harassment, intimidation, and violence [

17], which built on longstanding political traditions and cultural norms of white supremacy.

An early example of this process was the building of the Bohemia Spillway, a flood control feature located on the East Bank of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish south of the parish seat of Point a la Hache (see Barra [

28] for discussion). The Bohemia Spillway was opened in 1926 and was effectively a perforation in the levee system immediately downstream from the town of Bohemia (so named for its population itinerant “Bohemian” labors working in the industrial sectors of seafood production). Knowing that the spillway left downstream residents without levee protection, the Orleans Parish Levee Board bought out affected landowners (who tended to be black and/or poor) for pennies on the dollar. The board then made lease arrangements with oil companies and pocketed the enormous resulting monetary windfalls. Though there is debate about the exact details of timing and intention [

29], the result was that they Bohemia Spillway enriched the Orleans Parish Levee board, which utilized the money in constructing flood control systems to reclaim land and protect its growing urban population around New Orleans, while also often enriching themselves personally.

The notorious Plaquemines Parish political boss, Leander “Judge” Perez, developed a patronage system of political corruption in the expansion of oil extraction, using his power to intimidate and harass the local population, especially its poor and black members. Much is known of his deeds historically [

17], though I suspect that a good deal is not. For example, a key informant recalled a story from the 1960s in which his neighbor, a member of the parish’s civil jury dealing with land disputes, had his house burned down by Perez-backed thugs for opposing an oil drilling development. In contrast, others fondly remembered Perez’s patronage and the efficiency/effectiveness of his political machine. Perez’s propensity toward political violence is historically manifested in his deeds such as his explicit support for the Ku Klux Klan and his construction of an illegal dungeon (located just below the Bohemia Spillway) in which he planned to detain and torture 1960s Civil Rights-era protesters—all known to state and federal authorities at that time.

The late 1960s through early 1970s was a period of both significant political reform and an economic boom in the oil and gas industry. Though they were declining, oil and gas production levels were high as the result of the last major pulse of onshore oil extraction in Lower Plaquemines Parish. Once again, older residents remembered this time period fondly as one in which both household-level and community-level economic wellbeing tended to be strong and in which both oil industry employment and commercial fishing opportunities were abundant (see also Groth [

24]). Perez died in 1969 and any potential political succession within the family was split by a bitter feud between his sons. From that point, major political reforms and racial integration took place.

In this way, the history of the oil industry in Lower Plaquemines Parish fuels two starkly contrasting mindsets among residents: on the one hand, community members tend to have a favorable view of the industry as a source of economic opportunity and community-level support through time; on the other, there is often suspicion about the fusion of oil industry wealth and political power given such a deep history of political corruption combined with corruption, racial segregation, violence, and intimidation. As I will discuss further below, both modes of thinking are still very much alive in Lower Plaquemines Parish today.

2.2. Commercial Fishing and Oil and Gas Extraction in the Mid-to-Late 20th Century

Through time, and in spite of obvious instances of conflicting interests, there has been significant symbiosis between the oil and gas and commercial fishing industries in Southeast Louisiana [

23,

24,

27]. The oil and gas industry has provided small-scale commercial fishers alternative economic opportunities with which to supplement and buffer fishing returns and income. Coastal oil industry jobs generally required an overlapping set of marine/nautical skills, as well as knowledge of the landscape, etc. Likewise, coastal fishing communities provided the oil and gas industry with skilled marine labor in the form of workers capable of operating vessels and performing strenuous physical tasks under difficult local conditions.

I interviewed four commercial fishers who were old enough to have operated during the boom period of the 1960s-1970s. All stated that they had received significant income from the oil and gas industry, allowing them to purchase vessels, homes, vehicles, etc. Additionally, all recalled alternating between employment in the oil and gas industry and commercial activities either on a seasonal or year-to-year basis, depending on the relative quality of opportunities with both domains as well as other personal economic contingencies. When favorable oil industry employment was unavailable, they turned more to commercial fishing; when fishing conditions and market favorability were poor, they turned more to oil industry employment.

Such a relationship is strongly supported by Groth [

24], who found a significant negative correlation between the numbers of active oil and gas wells and levels of fossil fuel production and the number of commercial fishing licenses issued in Louisiana between 1976 and 1989. That is, as local oil production declined during this period, the number of commercial fishing license holders grew. In other words, as oil and gas industry economic opportunities declined, community members predictably turned to commercial fishing as a primary source of household income. The result was more fishers operating and doing so more intensively.

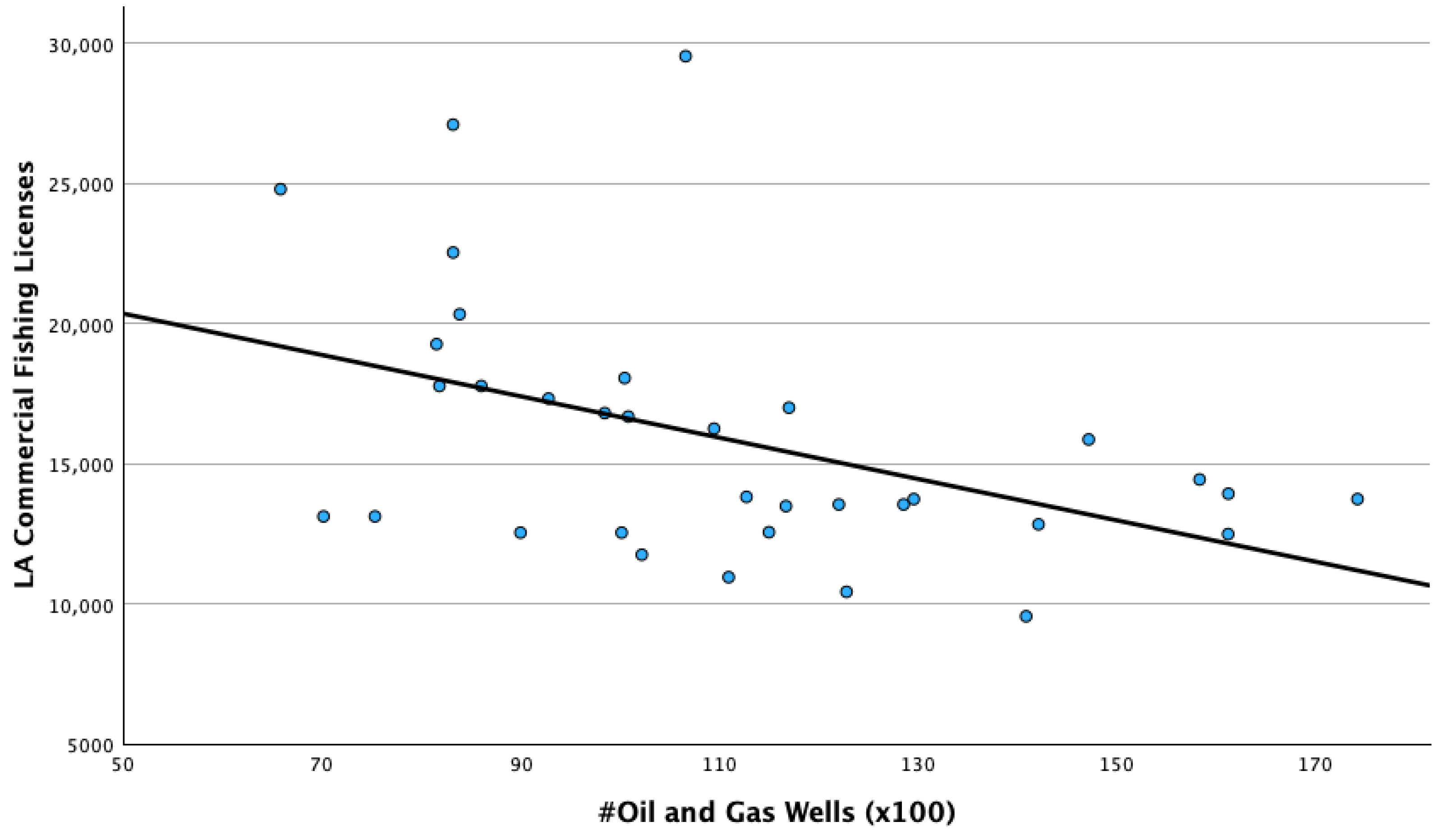

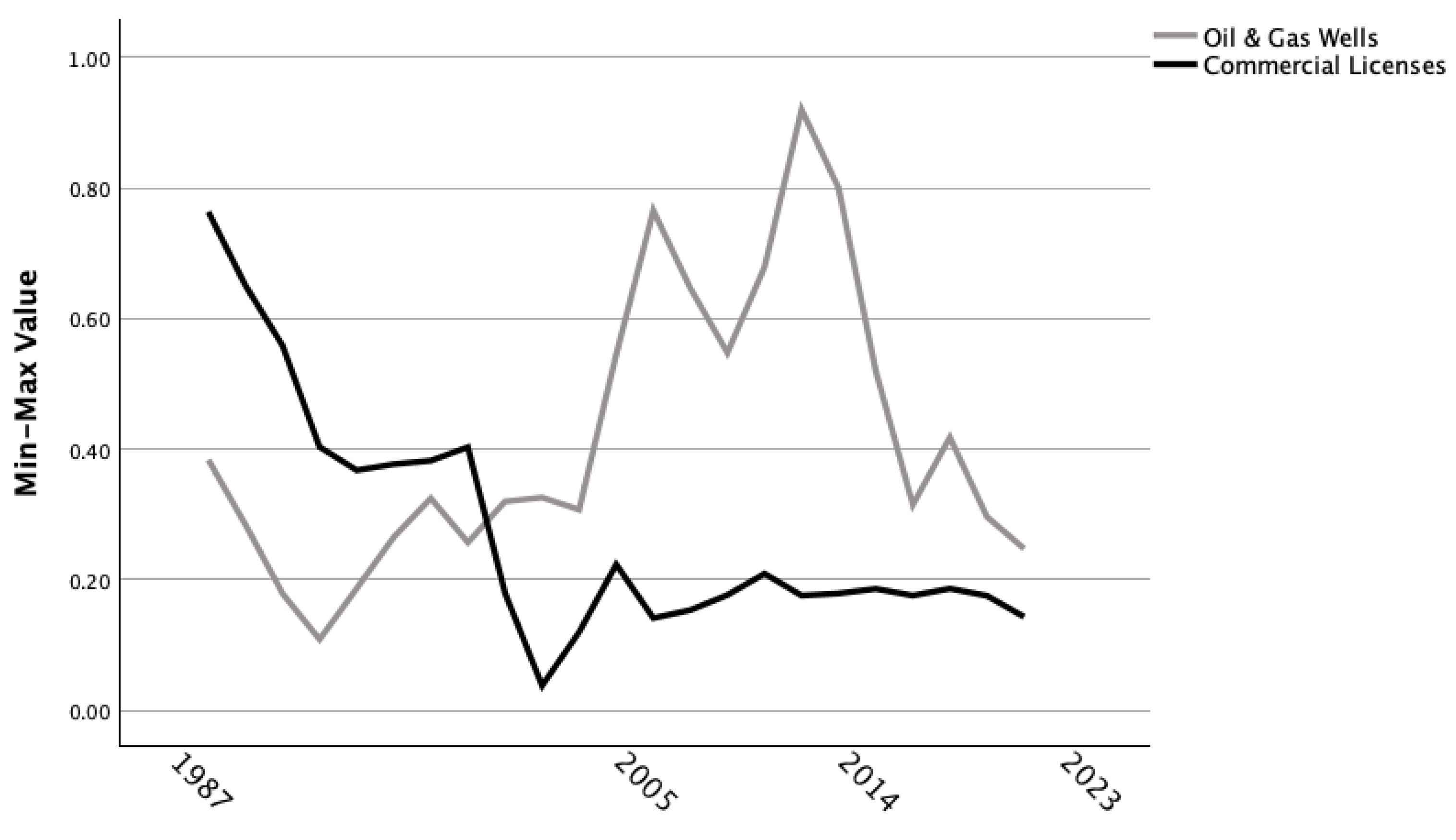

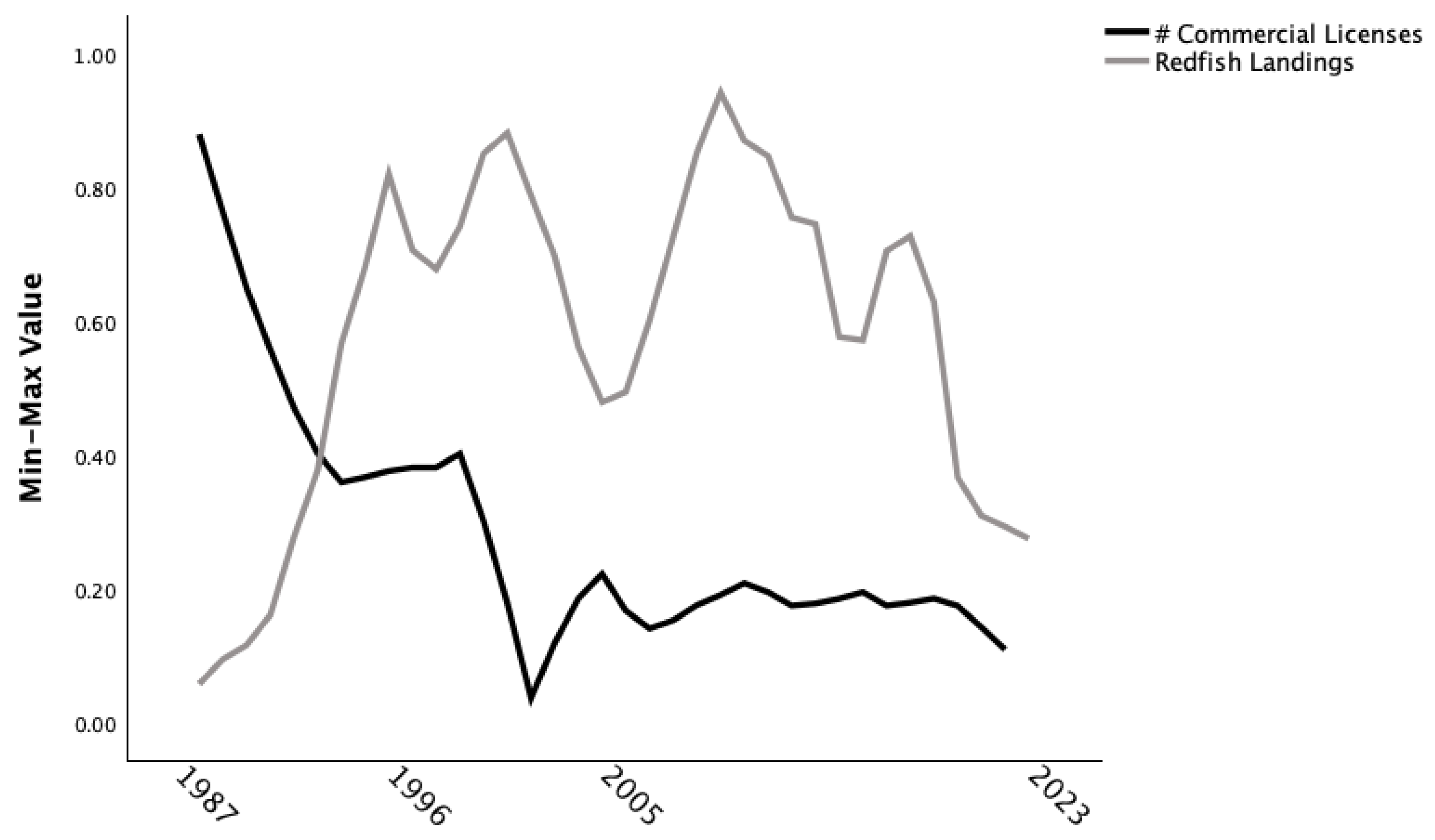

Crucially, more recent data show that this negative relationship has continued into the present even as trends in oil and gas production and commercial fishing have reversed.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the relationship between the number of active oil and gas wells nationally and the number of commercial fishing licenses issued by the state of Louisiana between 1987 and 2023 (

r2 = 0.205;

f = 8.259;

p = 0.007). Like Groth [

24], this analysis finds a lag in the relationship between oil and gas production trends and Louisiana commercial fishing license issuances. While Groth found a 2-year lag, this study finds a 3-year lag. The continuance of this relationship is largely the result of the correlated increase in oil and gas production and decrease in commercial fishing in the approximate decade between ~2004 and 2014. It is also worth noting that the period from 2015 to present sees this longstanding relationship largely break down, as both oil and gas production and commercial fishing in Louisiana remain low in concert. Such patterning points to an ongoing period of stress among coastal fishing communities characterized by both low commercial fishing income and limited alternative economic opportunities.

My ethnographic evidence suggests that the 1970s–1980s decline of the oil and gas industry in Southeast Louisiana had negative consequences in terms of an interrelated set of dynamics linking commercial fishing incomes, human–environmental impacts on fisheries/estuarine ecosystems, and community wellbeing. First, many informants recalled the above-described surge in commercial fishing, which was largely concentrated on the targeting of shrimp. For example, a white American fisherman in his 1970s described a trend in which increasing numbers of shrimpers led to the utilization of smaller-gauge trawling nets and larger motors, resulting in greater water bottom damage, bycatch, and overall fisheries declines. This interview was among the very few in which a commercial fisher ever acknowledged the prospect of overfishing.

The 1970s–1980s also saw a major wave of Vietnamese immigration into Southeast Louisiana, which overlapped with the decline in the oil and gas industry and increasing pressure on commercial fisheries. By the mid-1980s, Vietnamese refugees constituted a significant proportion of commercial fishers in Lower Plaquemines Parish (and beyond), which further crowded fisheries and accelerated tactical changes in shrimping techniques and technologies, such as those identified in the above-described interview. Sadly, this increasing stress and competition often played out acutely in racist terms for newly arrived Vietnamese populations.

Vietnamese shrimpers, who brought their own historical coastal adaptations to small-scale commercial shrimping, were quickly “othered” and demonized by local populations in departing from established local fishing traditions. The Vietnamese were often blamed for problematic aspects of intensification in terms of shrimping techniques, such as those mentioned above. In this way, there was the establishment of a kind of aesthetic hierarchy of shrimping techniques, technologies, and tactics in which Vietnamese commercial fishers were stigmatized. For example, to the degree that any commercial fishers were willing to acknowledge potential overfishing, they blamed the Vietnamese. In this way, Vietnamese immigrant populations likely experienced the negative social consequences of this period of increasing pressure on fisheries, many of which continue to be felt today.

2.3. Finfishing Adaptations in the Late 20th Century and Their Consequences

The commercial fishing stress of the 1980s led to a range of economic and social adaptations among the fishing communities of Lower Plaquemines Parish. As Groth [

24] points out, such adaptations were widely consistent with ecological predictions of both intensification and diversification. Intensification is bluntly indicated by increasing participation in the commercial fishing industry and more subtly in the evolution of shrimping tactics and gear. Diversification is indicated by an increased targeting of alternative species, especially finfish. The latter trend took advantage of the rise of new finfish markets in historically contingent ways. In this context, one market dynamic stands out as particularly salient: the role of New Orleans restauranteur Paul Prudhomme. In my fieldwork, I found near-universal consensus concerning the role of Prudhomme’s restaurant,

K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen, in creating demand for redfish (

Sciaenops ocellatus; see also [

30,

31,

32]).

K-Paul’s began serving a fish called blackened redfish in 1980, which became popular in a way that a seafood dish defined by a particular species had not previously. By the mid-1980s, nation-wide demand for redfish had soared. In Lower Plaquemines Parish and beyond, commercial fishers took advantage of this opportunity by increasingly targeting redfish using gill nets, which (among other things) constituted a key adaptive strategy in coping with increasing stress among the more prevalent commercial shrimping activities.

The craze resulting from the popularity of

K-Paul’s blackened redfish stands out in the memories of commercial fishers for important reasons. In providing an alternative target species associated with greater marginal value, this provided some relief in the context of broader economic decline among fishing communities. Perhaps more importantly, it increasingly brought commercial fishers into conflict with recreational fishers and impacts to redfish populations drew wider environmentalist scrutiny [

31].

During my ethnographic experiences, it was evident to me that the salience of the redfish craze in relation to the decline of the commercial fishing industry reflects consequential conflict and negative relations with outside populations with contrasting values. Realistically, however, it is overly simplistic to characterize the increasing emphasis on finfish harvesting as purely the fault of Paul Prudhomme. (For his part, Prudhomme regretted his negative impact on redfish conservation, saying in a Los Angeles Times interview [

30], “It would be tragic for me, personally, to know that redfish would be extinct [because of my actions].”) Among other things, commercial fishing for redfish was banned in Louisiana in 1988, yet other finfish harvesting continued as a major adaptive strategy for nearly another decade.

A more representative example of this phenomenon may be that of commercial mullet fishing (

Mugil cephalus; see McCall [

33]). A state report by Mapes et al. [

34], for example, states that commercial mullet landings averaged just under 88,000 lbs between 1972 and 1976. Between 1977 and 1994, this number skyrocketed to just under 3,500,000 lbs—an increase of nearly two orders of magnitude. Much of this surge in mullet harvesting was related to the expansion of the roe market from the late 1970s to the 1990s. However, it is also the case that the harvest of non-roe mullet, caught outside of the October–December breeding season, increased from near 0 before 1977 to nearly 4,000,000 lbs at its peak in 1994. Commercial mullet fishing, along with various other finfish species, emerged as a key alternative to shrimping during the downturn of the 1980s and into the 1990s, providing alternative target species as fisheries became more crowded and overfishing dynamics accelerated.

The period spanning the 1980s–1990s was a key one from the standpoint of political perceptions of the commercial fishing industry in Louisiana. This increased reliance on finfish harvesting had enormous consequences for political decision-making concerning the commercial fishing industry, as well as the status of small-scale commercial fishers among coastal communities. First, it was a time in which those outside of the commercial fishing industry began to encounter gill nets, purse seines, and other large-scale passive finfish gear in a major way for the first time. Such experiences were most direct among affluent sport fishers, who frequented the inshore coastal marsh in which gill net harvesting had increased the most. Recreational fishers did not like what they saw and naturally made the connection between an increasing presence of gill nets and other passive net gear and declining stocks of redfish and other sought-after sport fish species.

In that respect, there is a sense in which wider grumblings about potential overfishing were in the air. Far beyond any awareness of ecological impacts from the shrimp industry as it intensified, the aftermath of the redfish craze laid the cultural groundwork for alertness concerning the potential overfishing of those and other key species. The 1980s was also an inflection point in a certain strain of environmentalist thinking (see, for example, Woodhouse [

35]) in which commercial fishing and other extractive economic activities were increasingly seen in a negative light from the standpoint of ecological wellbeing and natural resource conservation. This amounted to a seismic shift in public perceptions of the commercial fishing industry in Louisiana and beyond.

2.4. Louisiana Commercial Fishing Restrictions in the 1980s–1990s

Among other things, the fallout from the redfish craze included a dramatic increase in lobbying by sport fishing interest groups, increased state-level regulation, and new approaches to legislation. First, the 1980s saw several waves of new licensing strategies and more stringent commercial fishing restrictions. In 1988, Louisiana banned the commercial harvesting of redfish and, in 1989, the state switched to its current discrete licensing system focused on gear types and individual vessels/vessel operators as units of registration.

This was also a time period in which commercial fishers were increasingly cast as “ecological villains” [

15]. In this vein, several media reports from the era pointed to the impact of a sensationalist news video showing commercial fishers dumping excess dead redfish in order to avoid violating an existing quota [

36]. Though such behavior was likely uncommon, the video was emotionally charged in suggesting both serious overfishing via overkills caused by gill net use and a kind of callousness among commercial fishers in being willing to kill/waste a valued resource. Such negative views of commercial fishers were also conflated with hostile stereotypes based on race, class, and nationality, often in combination with stereotypes having to do with crime, drug use, and poverty.

Older informants recalled insults from non-local sport fishers focusing on (for example) their lack of education, addiction issues, and concomitant criminal records, being called “drunks,” “crackheads,” “white trash,” etc. In general, the animus toward small-scale commercial fishers in places like Lower Plaquemines Parish took advantage of the fact that many small-scale commercial fishers did have problematic personal histories that tended to exclude them from formal wage labor opportunities, and so they gravitated to commercial fishing. The Vietnamese fishing community, which struggled with language, literacy, and cultural assimilation (as well as an overlapping set of social problems with those mentioned above), was also the subject of a great deal of racist vitriol (see also [

37] for discussion). Finally, long-standing racial prejudices against black fishers continued to play a role [

37].

With respect to Louisiana’s stricter and more complex commercial fishing licensing system, Groth [

24] argues that such measures amounted to an attempt at increasing social control over the behavior of small-scale fishers. Many coastal community members believe that updates to the licensing process were designed to differentially deter applications from minority groups, especially the Vietnamese. Such requirements took advantage of language and literacy problems, as well as up-front costs associated with license purchases. Similarly, Tang [

37] provides ethnographic evidence that new licensing systems were particularly aimed at eliminating competition for white shrimpers among the Asian and black communities.

This period of conflict and scrutiny culminated in dramatic parametric commercial fishing restrictions in the form of a state ban on saltwater gill net use. The impetus for such changes emerged first in Texas, which instituted a sweeping gill net ban in 1988 primarily aimed at preserving redfish stocks. This political movement was advanced by sport fishing lobby groups, especially the Gulf Coast Conservation Association (GCCA; today, the Coastal Conservation Association/CCA). In Florida in 1994, gill net use was banned via a popular constitutional referendum that pitted sport fishing and environmental groups, including the GCCA, against the commercial fishing industry. The results of this referendum were shocking to many, as it succeeded with around 72% of the popular vote. In the run-up to the referendum, sport fishing and environmental groups were able to spend millions of dollars on what Loring [

15] regards as “misleading propaganda” framing the negative effects of gill net use. This event represents a turning point in the balance between sport fishing and commercial fishing industries across the Gulf Coast, in addition to reshaping perceptions of fishers and fisheries.

Louisiana’s move to ban the use of gill nets drew greatly on Florida’s popular constitutional referendum [

36] and involved many of the same key players, especially the GCCA. In 1995, the Louisiana state legislature passed a comprehensive ban as the commercial fishing industry lost political favor relative to the more affluent and better organized sport fishing lobby [

36]. Here, it is important to point out that commercial harvesting of the most sensitive and contentious species, such as redfish, had already been banned previously in the 1980s (as it had been in other Gulf Coast states prior to their gill net bans). Louisiana’s gill net ban, then, was largely aimed at other commercial species and concerns about the negative ecological impacts of gill netting in terms of bycatch. The gill net ban also included a major carve-out for the harvesting of menhaden (known locally as “pogies”), which I will return to later in the paper.

It is an understatement to say that Louisiana’s gill net ban was a huge blow to the fishing communities in Lower Plaquemines Parish. It is remembered as a dark day by those old enough to have experienced the events firsthand and even younger generations are acutely aware of its legacy today. From an economic standpoint, it undercut the livelihoods of thousands of household-level commercial fishing operations. Some fishers retooled, either developing non-gill net capture approaches for alternative finfish species (e.g., hoop nets, long lines, etc.) or moving back into shrimping. Many left the commercial fishing industry altogether.

A number of scholars have documented significant trauma among the fishing communities in Florida that were severely affected by the implementation of the gill net ban and their villainization by neighboring populations [

15,

38]. At an economic level, this trauma is attested to by dramatic increases in unemployment claims, food stamp applications, and data pointing to fishers exiting the commercial fishing industry [

38]. At a social–psychological level, this trauma manifested in terms of mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, anger, low self-esteem, and drug/alcohol-use disorders [

38]. Furthermore, this research suggests that such trauma was not evenly distributed across fishing communities but was rather disproportionately concentrated among its most marginalized elements.

Though little research of this kind was performed at the time of Louisiana’s gill net ban, my ongoing research in Lower Plaquemines Parish suggests that precisely the same set of negative economic, social, and social–psychological impacts occurred. Another consequence, of course, has been lingering resentments between sport and commercial fishers. On the one hand, many sport fishers continue to see commercial fishers through the lens of their social problems and often in relation to racial and/or class stereotypes. On the other hand, coastal commercial fishers remain hostile and bitter toward the affluence, political–economic power, and organization of sport fishers. In Plaquemines Parish, such negative feelings combine with the region’s long history of inequality and exploitation at the hands of powerful outsiders, which the sport fishers clearly are.

3. The Era of Disasters and Its Consequences

The recent history of Lower Plaquemines Parish has been greatly defined by disaster. Foremost, in August of 2005, Hurricane Katrina made its Louisiana landfall in Lower Plaquemines Parish, bringing profound human tragedy and catastrophic damage. In the end, Hurricane Katrina was the worst natural disaster in United States history, costing nearly USD 180 billion (2025 inflation-adjusted) and claiming more than 1800 lives. Lower Plaquemines Parish bore the initial brunt of that disaster and was devastated by it. Then, in 2010, the B.P. oil spill released more than 87 million barrels of crude oil into the Barataria basin, doing untold damage to local marine ecosystems, fisheries, and (thereby) fishing communities. Since that time, there has been a noticeable change in the discourse surrounding Lower Plaquemines Parish and adjacent portions of Louisiana’s coast.

First, Hurricane Katrina starkly illustrated the levels of tropical storm risk inherent to life in Lower Plaquemines Parish as a narrow strip of land between two levees jutting out over 100 km into the Gulf of Mexico. After the storm, state and federal authorities began to wonder out loud if ongoing dynamics in terms of climate change, sea level rise, coastal erosion, and increasing tropical storm frequency/strength simply meant that Lower Plaquemines Parish was too risky for people to inhabit (see also McCall et al. [

39]). It also focused attention on the role of Louisiana’s coastal marsh in buffering storm surges and the way in which that mechanism had failed in catastrophic fashion thanks to coastal erosion. Louisiana’s coast became a kind of engineering problem to be solved, and one of importance not just for coastal communities but for urban centers like New Orleans and beyond.

Smith [

40] says of Hurricane Katrina, “there’s no such thing as a natural disaster,” and that is as true for Lower Plaquemines Parish as it was for New Orleans. While that statement is true in various dimensions, it is worth noting that the erosion of the coastal marsh was greatly exacerbated by the 20th century construction of pipelines, canals, and other oil and gas infrastructure. This industrial fragmentation of the coastal marsh has created openings for storm surges and other eustatic sea level events, which have accelerated erosion, saltwater intrusion, and other negative dynamics from the standpoint of ecological and landscape stability.

Next, the 2010 B.P. oil spill is among the costliest and ecologically damaging technological disasters of the 21st century. Lower Plaquemines Parish fishers, whose seafood harvesting seasons were disrupted at the scale of years, were heavily involved in cleanup activities, on the one hand benefitting financially but on the other hand suffering the effects of chemical exposure from dispersants. Ultimately, the B.P. oil spill was settled for over USD 32 billion (2025 inflation-adjusted), a good deal of which went towards compensating affected fishers. The region has also been impacted by countless smaller-scale oil spills and chemical pollution events, both before and after the B.P. oil spill—many of which were linked to the degradation and abandonment of oil and gas wells and other infrastructure. Finally, billion-dollar litigation remains pending over the effects of such oil and gas infrastructure, including its effects on coastal erosion, in spite of numerous attempts to block it on the part of both oil companies and allied state political interests.

In my fieldwork, a common theme in discussions with Lower Plaquemines Parish residents has had to do with a general feeling of being cumbersome to the evolving outside interests in the region and the existence of political–economic conspiracies to depopulate the coast. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, nearly all resident households had some form of negative interaction with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) [

39]. Across these negative interactions, residents recalled feeling unfairly blamed by FEMA agents for planning failures or simply for choosing to live in such a risk-prone location in the first place. For their part, FEMA officials felt unfairly targeted by negative media attention and political discourse in handling what was essentially an impossible situation [

39]. Such concrete government agency interactions articulated with broader and more abstract public debates about the future of coastal communities, including both the ethical appropriateness and practicality of their continued existence—and at the same time, plans were emerging to relocate other nearby coastal communities (e.g., [

39]).

Interactions with the oil and gas industry following the B.P. oil spill also contributed to the broader feeling of being unwanted. Most fishers’ experiences during the oil spill cleanup tended to be negative, with fishers perceiving B.P. as being driven mostly by coverup and payoff rather than true environmental motives. Later, in seeking financial compensation through legal channels, many fishers were required to show extremely detailed documentation of previous fishing income prior to the oil spill, which they naturally struggled to do. Once again, issues of language and literacy loomed large, as well as the complexity and importance of informal economic systems situated at the nexus of small-scale commercial and subsistence-level fishing [

17].

Such interactions with both the corporate apparatus of B.P. and the governmental legal system left fishers feeling mistrusted, resurrecting many of the raw feelings from being villainized during the movement to ban gill nets. On the other side of the fence, B.P. officials felt taken advantage of by local populations, who had developed significant legal sophistication in litigating smaller-scale pollution events in the past. Thus, many fishers came to perceive their own existence and that of their communities as a financial liability to the oil and gas industry, just as the oil and gas industry increasingly saw coastal communities in terms of potential legal liability.

Recently, a new chapter in the complex relationship between fishers and the oil and gas industry has begun with the construction of the Venture Global liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal near Myrtle Grove. This facility is designed to be among the largest of its kind on Earth and, to underscore that point, the loan acquired for its building was (at the time) the largest financial transaction in human history. The construction of this facility has taken place using almost entirely non-local labor and has mostly benefitted relatively affluent landowners with the property capacity to rent houses, trailers, apartments, and trailer hook-ups to itinerant plant construction workers. Meanwhile, the extra-local labor force has put a huge strain on local infrastructure, traffic, and parish services. On top of everything else, the plant is designed to be operated by only a few hundred skilled workers and, as such, would not provide much meaningful employment opportunities to local communities (though I am aware of several commercial fishers who have found lucrative employment there).

Many residents have openly questioned the wisdom of placing perhaps the world’s largest explosive materials site in perhaps the world’s most disaster-prone location (a concern I share personally, as my home is less than 50 km from the plant). Others hold concerns about the risks and impacts of the oversized LNG tankers in the Mississippi River, as well as the potential for other forms of pollution and chemical releases. Though there are clearly some economic benefits for Plaquemines Parish in terms of employment, tax base, etc., many view these as small compensation for taking on the risk of major technological disaster in ways that would be unacceptable for nearby urban areas, such as New Orleans (though, in reality, the plant is more out of sight than truly distant from New Orleans). As usual, many residents fear that such economic benefits will be primarily focused on affluent parish and state elites, leaving poorer communities to shoulder the burden of risk and disruption with few (if any) of the rewards. In this situation, community members also recognize themselves as both unnecessary to the operation of the plant and the main vector of risk stemming from its operation in the event of technological disaster.

The result of these and other outgrowths of disaster and disaster risk have led many Lower Plaquemines Parish residents into a kind of paranoia concerning outside elite conspiracies to eliminate them and other coastal populations in Southeast Louisiana. Furthermore, emic ideas about the motivations of such potential conspiracies tend revolve around the clearing out of a population-free industrial corridor of oil and gas production, refinement, and export. Fishing relates to this set of beliefs in as much as fishers have borne the brunt of the ecological damage caused by technological disasters, they have been at the center of resulting financial settlements, and there has been a great deal of tension with oil and gas companies over all of the above.

3.1. The Role of Oil and Gas in the Regulation of Louisiana’s Coastal Fisheries

Clearly, the roles of and relationships between the oil and gas industry, small-scale commercial fishing, and coastal communities such as those in Lower Plaquemines Parish are complex and deep intertwined. My belief is that there were two crucial turning points in this relationship: one that spanned the 1980s–1990s during the coupled downturn of the oil and fishing industries, and the

Era of Disasters following Hurricane Katrina and the B.P. oil spill event. The relationship between oil and gas and the commercial fishing industry had, at one time, been mutualistic [

23,

27]. The

Era of Disasters saw the interests of and perspectives on the oil and gas and commercial fishing industries diverge fundamentally.

As opportunities for maritime oil and gas employment dried up, pressure on the commercial fishing industry increased—as did economic stress among fishers. As commercial fishers adapted in taking advantage of emerging finfish markets, they increasingly came into conflict with sport fishers over resource allocation issues. The villainization of fishers began to occur in ways that it had not previously when there was greater economic and cultural overlap with the oil and gas industry—with issues of race, class, and nationality playing key roles. In this regard, there is an important sense in which the aesthetics of the commercial fishing industry and the people in it changed through this period: small-scale commercial fishers became poorer, less white, and more prone to the social problems typical of rural poverty, and they became more likely to come into conflict with affluent sport fishers.

The period of time between the banning of commercial harvesting of redfish in the 1980s and the banning of gill nets in the 1990s can be characterized in terms of a serious increase in the levels of political organization and influence on the part of sport fishing lobby groups, particularly the GCCA. In a 1996 New Orleans Times-Picayune interview, Louisiana state legislator Randy Roach summed up the political developments as follows:

“For several years there was pretty much political parity on the issues between sports and commercial fishing interests. Things went 50–50, or maybe 55–45, one way or the other. It was usually pretty close. But in 1995, the sports lobby came back and … Wham! Suddenly they were on top 90–10. They literally steamrolled the opposition on the gill net ban, something they had been only able to talk about for 10 years. I mean, it was no contest. Sudden, complete dominance. That is a very rare thing in politics.”

This surge in the political influence of the sport fishing lobby was closely accompanied by the decline and fragmentation of the commercial fishing industry as incomes declined and various internal tensions—racial/ethnic, regional, target species, etc.—limited organizational cohesion.

Such a rise in the political influence of sport fishing was clearly driven by a combination of wealth and social status on the part of the sport fishing lobby. Sport fishing of the kind at stake in this historical political contention tends toward financial affluence as it requires a great deal of expensive equipment in terms of vessels, towing vehicles, fishing tackle, and leisure time. As many have pointed out, fishing regulations, such as the gill net ban, are effectively aimed at resource allocation conflicts; there are only so many sought-after fish in coastal environments and the sport fishing lobby staked a political claim to a larger share of those resources via gear limitations and bans on certain kinds of commercial fishing [

15,

24,

40]—a fact even recognized by many sport fishers [

32]. In such an instance, the affluence of sport fishers provides financial resources with which to organize politically and to utilize in influencing the political process through lobbying.

Even the political influence of the sport fishing lobby has its limits, however. A counterexample in terms of the political context of parametric commercial fishing regulations is that of the menhaden industry. Menhaden (Brevoortia sp.) are a small baitfish species mostly utilized in the production of fish oil, fertilizer, pet food, and other industrial products. In contrast with the small-scale commercial fishing at the heart of this paper, menhaden are processed by large multi-national industrial fishing corporations: in the case of Plaquemines Parish, Daybrook Fisheries, a South Africa-based company, which is the largest private employers in the parish. Menhaden are harvested by a fleet of large fishing vessels, known locally as the “pogie boats,” which deploy kilometer-long purse seines and sometimes utilize spotter aircraft to identify schools. Today, according to the CCA (unpublished data), 97% of Louisiana’s finfish harvest consists of menhaden.

Naturally, sport fishers and environmentalists have had major concerns about the scale of menhaden fishing, its gear and tactics, and its ecological consequences [

41]. The issue of bycatch is clearly problematic, as is the broader ecosystem damage of removing key baitfish species and harming nearshore water bottoms. CCA Louisiana has, for some time, vocally opposed industrial menhaden harvesting and supported potential state legislation to restrict it. To this point, however, such efforts have largely been in vain, though a half-mile buffer zone around sensitive shorelines was recently created. The menhaden fishing industry, with its own concentration of wealth and lobbying power, has been able to resist such regulatory pushes in ways that the poorer and more fragmented elements of small-scale commercial fishing were unable to.

3.2. Beliefs About the Influence of the Oil and Gas Industry and Contemporary Commercial Fishing Regulations

Interestingly, many commercial fishers I spoke to in Lower Plaquemines Parish drew connections between the actions of the sport fishing lobby and the deeper motivations of the oil and gas industry. For example, one fisher pointed out major linkages between the oil and gas and chemical industries and the leadership of the GCCA/CCA in Louisiana. Such claims do, in fact, hold some truth: for example, the outgoing CEO of CCA Louisiana recently accepted a position as President and CEO of the Louisiana Chemical Association. Currently, a significant number of CCA Louisiana officer positions are held by individuals with direct connections to the oil and gas and/or chemical industries, with several others having held relevant regulatory positions in state government, and still others with backgrounds including lobby, marketing, and public relations. The belief inherent to this point of view is that the oil and gas industry is using commercial fishing regulations to wipe out coastal fishing communities based on the view of coastal communities as a liability and threat to their industrial activities and future interests.

Such emic beliefs clearly interlink with the negative historical pattern of interaction in which industrial political–economic elites have used their power to remove obstacles to development posed by fishing communities—a pattern that seems to have reemerged in the

Era of Disasters. Since Hurricane Katrina, there have been countless policies and projects that make everyday life harder and government rhetorical stances on coastal restoration that often frame coastal populations as impediments to environmental progress [

19,

28]. As Hunter S. Thompson put it, “Smart people understand there here is no such thing as paranoia.”

I am not convinced that there is a clandestine “smoke-filled room” in which oil and gas “robber barons” have made secret plans to use the CCA (and other such groups) to kill off coastal communities by pushing for stricter fishing regulations. I do, however, see the heavy overlap between the powerful sport fishing lobby and the oil and gas industry as a prime source of wealth and power in Louisiana; and also a broader sense in which affluent sport fishers have embraced negative narratives about coastal communities based on a combination of environmental, economic, social, and cultural grounds to justify the harm that increased regulation might cause to those fishing communities. The oil and gas industry has been an outsized source of wealth in Louisiana for more than a century; therefore, a large number of financially affluent and politically powerful individuals have ties to it, as well as to sport fishing and its lobby groups such as the CCA.

Furthermore, in seeing such connections and in having consistently negative encounters with affluent sport fishers, small-scale commercial fishers tend to view resulting fishing regulations as unfair and perhaps corrupt. This is obviously problematic since commercial fishers who see no justification in the fishing regulations that govern them will often seek to test their boundaries or evade them. Indeed, my participant observation research consistently demonstrated the willingness of fishers to push the limits of fishing regulations in terms of gear, species, catch limits, seasons, etc. As one commercial fisher told me, “All this time you were fishing with me, you didn’t know you were fishing with an outlaw!”

Current relations between fishing communities and sport fishing lobby groups exist in a longer-term historical context of resource allocation conflict. Since the early 20th century, there have been numerous instances in which oil industry wealth and political corruption led to the mistreatment of coastal fishing communities, which have tended to be poor and politically marginalized. When Louisiana commercial and sport fishers entered into a dispute over fisheries resource allocation (sensu Turvey [

42]), the wealthier and more powerful of the groups prevailed in structuring fishing regulations to their liking. In a deeper sense, much of this conflict was driven by aesthetics, both in terms of the perceptions of shifting commercial fishing targets/tactics and in terms of the fishers themselves.

3.3. Unintended Consequences of the Gill Net Bans

Smith and colleagues [

38] and Loring [

15] observe that the 1990s gill net ban in Florida likely had problematic unintended consequences from the standpoint of conservation and fisheries management. This includes increased pressure on stone crab stocks, as crab traps remained one of only a few legal gear options. Furthermore, while certain finfish stocks increased, many did not, which may be attributable to the persistence of problematic recreational fishing practices—especially in terms of fishing charters, which developed strategies for evading catch limits. All of the above could also be said of gill net ban impacts in Louisiana, which clearly did not fix many of the intended problems from the standpoint of redfish and other valued sport fish species, and which has suffered from the effects of ongoing problematic sport fishing practices.

One outcome of Louisiana’s gill net ban was the narrowing of commercial fishing targets to shrimp more exclusively. Shrimp trawling has remained legal, of course, and shrimping has continued to offer a viable economic opportunity for small-scale fishers, if not as profitable as it had once been at the market’s peak. While the consequences of this dynamic are contested, they are likely not positive in either ecological or economic terms. Shrimpers are quick to downplay the ecological impacts of trawling, which is understandable given the ways in which concerns about ecological damage have been weaponized against coastal fishers in the past. Trawling does, however, have impacts in terms of its bycatch and damage caused to water bottoms [

43] (see Jones [

44] for review). Conversely, there is a scientific consensus that fishers diversifying their targets is ecologically advantageous in contrast to more intensively harvesting a single species (e.g., [

45]), and this is exactly what small-scale fishers in Louisiana would have done if left to their own devices.

Perhaps the most important aspect of my ethnographic research in Lower Plaquemines Parish, however, has been in demonstrating the key role of subsistence fishing in buffering economic variability and risk at short-term time scales. Coastal fishing community residents rely heavily on subsistence fishing in general as a means of supplementing cash incomes. They do so more acutely, however, in response to economic shortfalls caused by disruptions and shortfalls associated with shrimping. As a result, coastal fishing community residents go fishing for subsistence purposes frequently, often organizing into parties and utilizing small fishing vessels. Fishers will then catch as much as they can, filling their freezers with fish. Perhaps most importantly of all, they share surplus fish through close social networks of sharing and reciprocity [

19,

34].

Subsistence fishing and concomitant networks of sharing and reciprocity are thus key mechanisms by which community members cope with both large-scale economic shortfalls and also acute personal hardships—the breaking down of a vehicle, damage to a roof from a storm, someone breaking a bone, etc. They are also key social systems in coping with the larger-scale risk posed by tropical storms and other disasters. For example, in recovery from Hurricane Ida in 2021 (a major hurricane that made landfall just to the west of Plaquemines Parish), I saw many ways in which residents collaborated in the recovery process, repairing structures and vessels, and otherwise dealing with the vast range of economic disruptions caused by the storm. Such networks of cooperation were very much the same channels through which food resources acquired through subsistence-level fishing activities were shared.

From an anthropological perspective, subsistence fishing in combination with social systems of sharing and reciprocity is strikingly reminiscent of the features of generalized reciprocity observed among forager societies (and other small-scale societies) across the globe [

46]. The fact that such strategies of economic risk buffering continue to play such an outsized role in the 21st century among coastal communities in a rich industrialized nation is a testament to their enduring value in buffering the return variability inherent to natural resource harvesting economies.

This sets up an important and seemingly paradoxical relationship between commercial fishing and subsistence fishing activities: the worse commercial fishing (primarily shrimping) conditions become, the more coastal community residents turn to subsistence fishing to buffer the resulting negative economic impacts through a sophisticated combination of technical, technological, and social strategies. Ironically, the fish species that are most negatively impacted by such forms of subsistence fishing are the ones that have been most contentious in the conflict between commercial and recreational fishers in the past: above all, redfish.

While subsistence fishers do not have the same cultural valuation of redfish as do their sport fishing opposite numbers, they do consume consequential quantities of redfish. During my subsistence fishing participant observation activities in Lower Plaquemines Parish, I directly observed the capture and consumption of more than 20 species of finfish, in addition to several species of duck (various species of Anatidae), nutria (Myocastor coypus), and feral hogs (Suis domesticus). As a matter of scale, subsistence fishers tend to focus more on species with higher catch limits, such as blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus), which has no catch limit locally. With that said, they are clearly extremely diverse and adaptable in their fishing targets and tactics, and will gladly keep a limit of redfish (or any other species valued by sport fishers) if the opportunity arises.

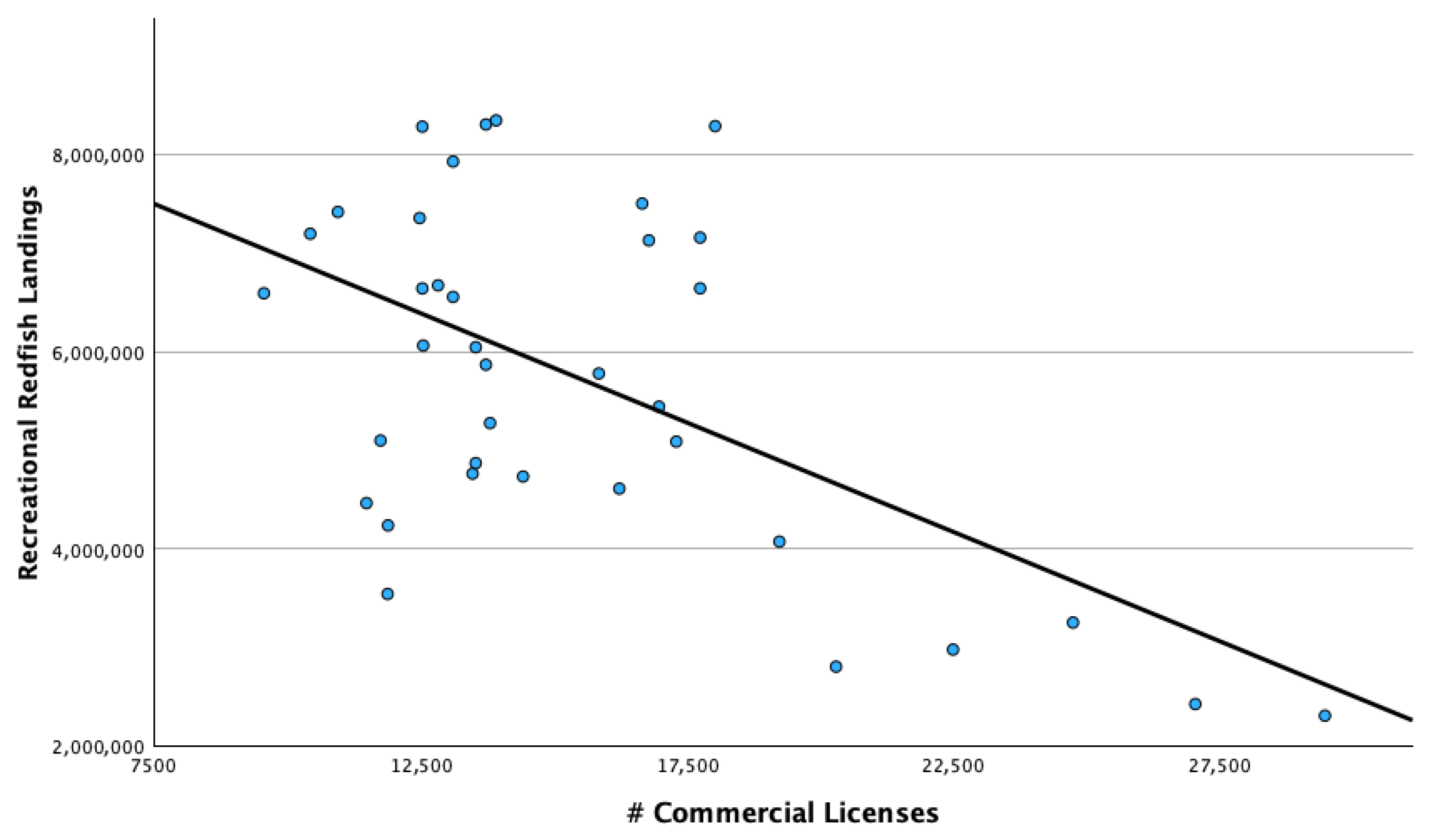

Another simple statistical analysis demonstrates this fact.

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the number of commercial fishing licenses issued and recreational redfish landings in Louisiana between 1987 and 2023. This relationship is once again negative and strongly statistically significant (

r2 = 0.305;

f = 17.011;

p < 0.001).

Figure 5 shows these trends through time with a clear surge in recreational redfish landings

after the imposition of the gill net ban. It is evident that this relationship would be even stronger if it were not for the major disruption to fishing caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The negative relationship between numbers of commercial fishing licenses and recreational redfish landings clearly reflects the fact that as commercial fishers lose access to formal fishing income, they adapt by turning increasingly to subsistence fishing.

It is worth noting that the gill net ban has not prevented a major, long-term decline in stocks of redfish, as well as other valued recreational species. Louisiana Department of Fish and Wildlife [

47] stock assessments show redfish populations have been declining steadily since the gill net ban of the mid-1990s, with the sharpest decline occurring from 2010 to present. This phenomenon has long been known to sport fishers, who have found it to be harder and harder to catch redfish in the usual places [

32]. This trend was also acknowledged by the State of Louisiana in their recent lowering of redfish catch limits from four fish between 16 and 27 inches (40.6–68.6 cm) and one fish greater than 27 inches (68.6 cm) to four fish between 18 and 27 inches (45.7–68.6 cm) and no fish over 27 inches.

On the one hand, there is a consensus across all parties that coastal environmental degradation in the erosion of the brackish marshes around the Mississippi River Delta has played a major role in the redfish decline, as well as a broader and potentially more troubling decline in productivity across a wide range of fish species. On the other hand, it seems likely that recreational/subsistence fishing has also played a key role in this decline as the primary human–environmental interface in reducing redfish numbers. In this respect, commercial fishers often pointed out loopholes utilized by charter fishing captains in circumventing redfish limits, principally by inflating the number of crew and passengers aboard vessels to increase the total vessel-scale limit. This, too, was addressed by Louisiana’s recent update to sport fishing regulations, which now prohibits charter fishing crew members from keeping redfish and other sport fish species (or contributing to the limit of paying passengers), as they had previously.

To a great extent, the impetus to ban gill nets in the 1990s was based more on emotional arguments than a scientific assessment of fish populations [

15]. In this respect, my research suggests the push to ban gill nets was the result of cultural perceptions of a combination of conflated phenomena, including the negative racial/ethnic and class characteristics of coastal fishing communities, the ecological morality of gear types, and impacts on a valued sport fishing resource. The ironic outcome of the gill net ban, which was greatly aimed at conserving redfish, is that it may have led to more redfish harvesting in the long run, albeit at the subsistence rather than commercial level. Neither of these outcomes can be considered positive in social, economic, and ecological terms; relative to the specific objectives of enhancing redfish and other valued game fish species, they seem likely to have been at best ineffective and at worst counterproductive.

3.4. Coastal Community Wellbeing and Fisheries Regulation in Louisiana: An Alternative Synthesis

The findings of this paper clearly hold implications for issues of coastal community wellbeing and resilience. As it pertains to socio-ecological systems (SESs), resilience conventionally refers to the ability of systems to withstand shocks, cope with stresses, and adapt to change over time without losing their holistic functional identity. In the context of this discussion, the concept of spatial resilience—that is, SES resilience characterized by spatially contingent contextual heterogeneity, complexity, and variable system component interdependency (among other things; see Cumming [

48] for a more complete definition)—is particularly salient.

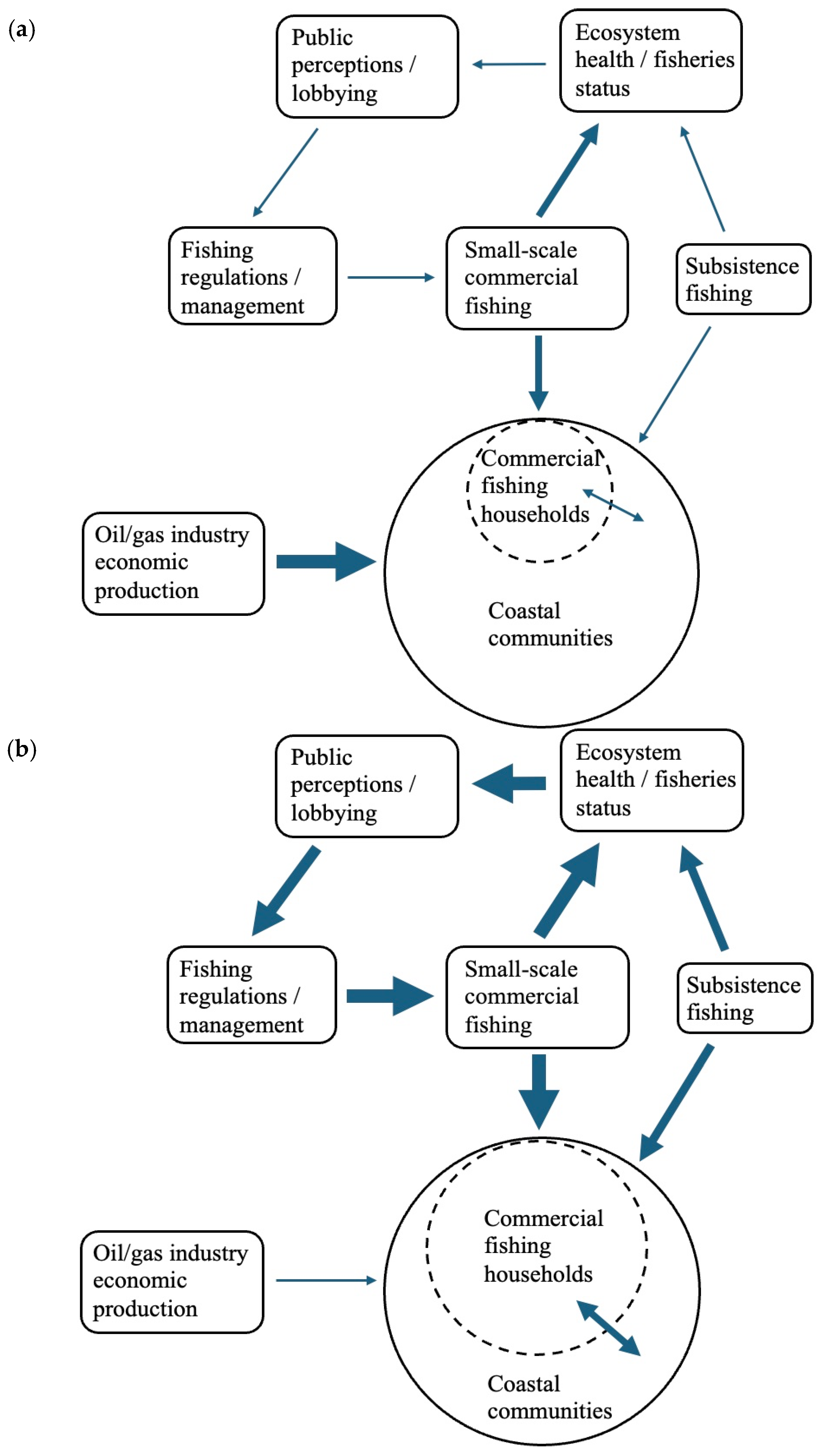

In Lower Plaquemines Parish, it is evident that commercial and subsistence fishing are themselves key components of social resilience, as community members have utilized these activities to buffer the impacts of shifting patterns of economic stress through time. From a spatial resilience standpoint, community interactions with the oil and gas industry influence the intensity of commercial fishing activities, as well as a feedback loop of ecosystem/fisheries impacts, public perceptions, sport fishing lobbying activities, and fishing regulations (

Figure 6). There have been significant periods of time, principally during the mid-to-late 20th century, in which oil and gas industry activities supported coastal communities, allowing commercial fishers to participate in fishing activities more selectively, thus reducing pressure on key fisheries and human impacts on coastal marsh ecosystems (

Figure 6a). There have also been major time periods in which the oil and gas industry has contributed less economically—leaving aside the negative impacts of disasters, pollution, and political corruption. In such periods, coastal communities have relied more exclusively on commercial fishing at the household level in the absence of other economic opportunities, amplifying the impacts of fishing activities on fisheries and ecosystems and triggering a negative feedback loop of public perception, sport fishing lobbying, increased commercial fishing regulation, and further intensification of fishing activities (

Figure 6b).

The findings described in this paper also suggest ways in which decreasing commercial fishing target diversity has differentially impacted various SES components, with widespread negative outcomes in terms of wellbeing and resilience for both human communities and ecosystems. A key aspect of this phenomenon is the fact that fishing regulations, which have narrowed the range of commercial fishing options, have had disparate but related impacts on coastal aquatic ecosystems and human social systems. Much of this was by design: it was understood that tightening commercial fishing regulations—above all, in the major shock that was the banning of gill nets—would have negative consequences for coastal fishing communities. Such regulations were represented as a tradeoff in protecting valued game fish species and occupying higher trophic levels, as well as the aquatic ecosystems in which they live.

This patterning points to two important spatial characters of tightened parametric commercial fishing regulations. First, increased fishing restrictions may harm coastal communities beyond just the direct impacts to commercial fishers caused by lost income. Instead, resulting economic stress ripples through communities, amplifying the effects of social problems and dynamics of vulnerability, such as addiction, mental illness, domestic violence, etc., and promoting the role of social network support in coping with stress and disaster. In other words, commercial fishing difficulties affect everyone in the community, taking away resources in dealing with both the widespread social problems that are common to rural regions of the US today and acute coastal issues having to do with climate change, disaster risk, etc. Second, such regulations have negative ecological consequences in forcing commercial fishers to intensify their activities within very narrow channels of species-specific and localized fishing activities. This also increases the role of subsistence fishing aimed at sought-after high-trophic-level finfish species as a means of buffering downturns and shortfalls—the exact opposite of the intention of commercial fishing regulations.

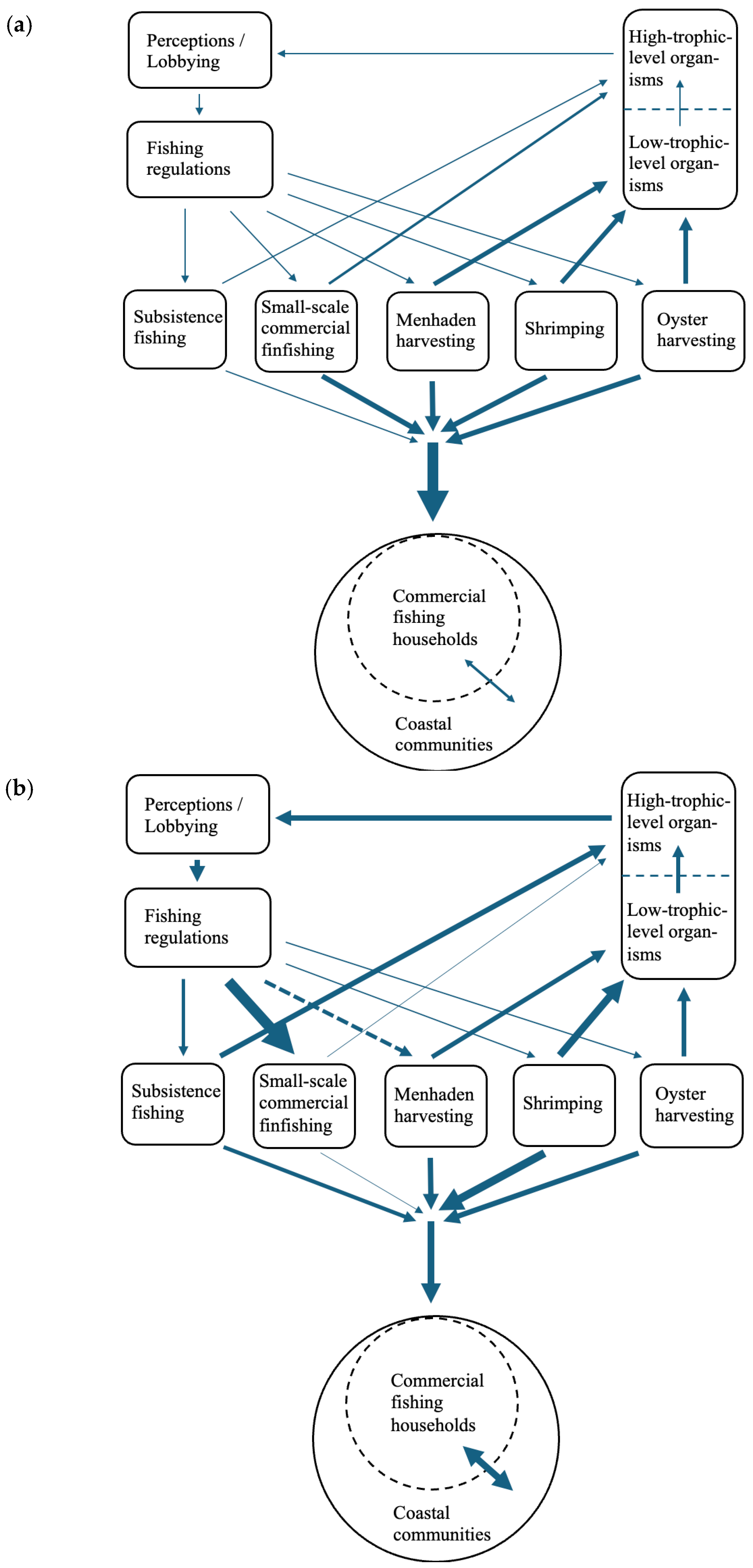

Figure 7 represents the relationships between different forms of fishing activity, environmental impacts, public perceptions and lobbying, fishing regulations, and community wellbeing. One system state, typical of the mid-to-late 20th century pre-gill net ban era, was characterized by more diverse and distributed community-level economic contributions from the commercial harvesting of shrimp, oysters, menhaden, and other finfish (

Figure 7a). In this pattern, fishers were able to adapt to shifting economic and environmental conditions by moving between various seafood targets and opportunities. Fishing activities were mostly aimed at low-trophic-level species but there was the capacity to target higher-trophic-level species at small scales in buffering the impacts of situational downturns (i.e., bad shrimp/oyster seasons, low market prices, tropical storm impacts, etc.) or situational opportunities. As such, commercial fishing impacts on the most visible higher trophic levels of aquatic ecosystems were mostly relatively small and unproblematic from the perspective of sport fishers/the general public. Such systems were also economically productive in providing resources that flowed through community social systems and played an important role in community wellbeing and resilience.

In contrast, a feedback loop existed in which increasingly strict fishing regulations led to reductions in the diversity of fishing opportunities, reduced overall economic production, increased vulnerability to downturns and disruptions, and increased subsistence-level fishing as an adaptive response (

Figure 7b). Under such conditions, community-level socioeconomic stress is effectively transferred to the higher trophic levels of aquatic ecosystems via subsistence fishing, harming stocks of sought-after sport fish species. In contrast, contributions from menhaden and oyster harvesting are relatively fixed and stable, as menhaden harvesting is conducted utilizing corporate-owned industrial fishing vessels and factory processing facilities and oysters are mostly harvested from privately held water bottom leases. Thus, household-level commercial fishing adaptations have focused almost exclusively on shrimp, with subsistence fishing playing an outsized role in buffering economic disruptions.