Atmospheric Drivers and Spatiotemporal Variability of Pan Evaporation Across China (2002–2018)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

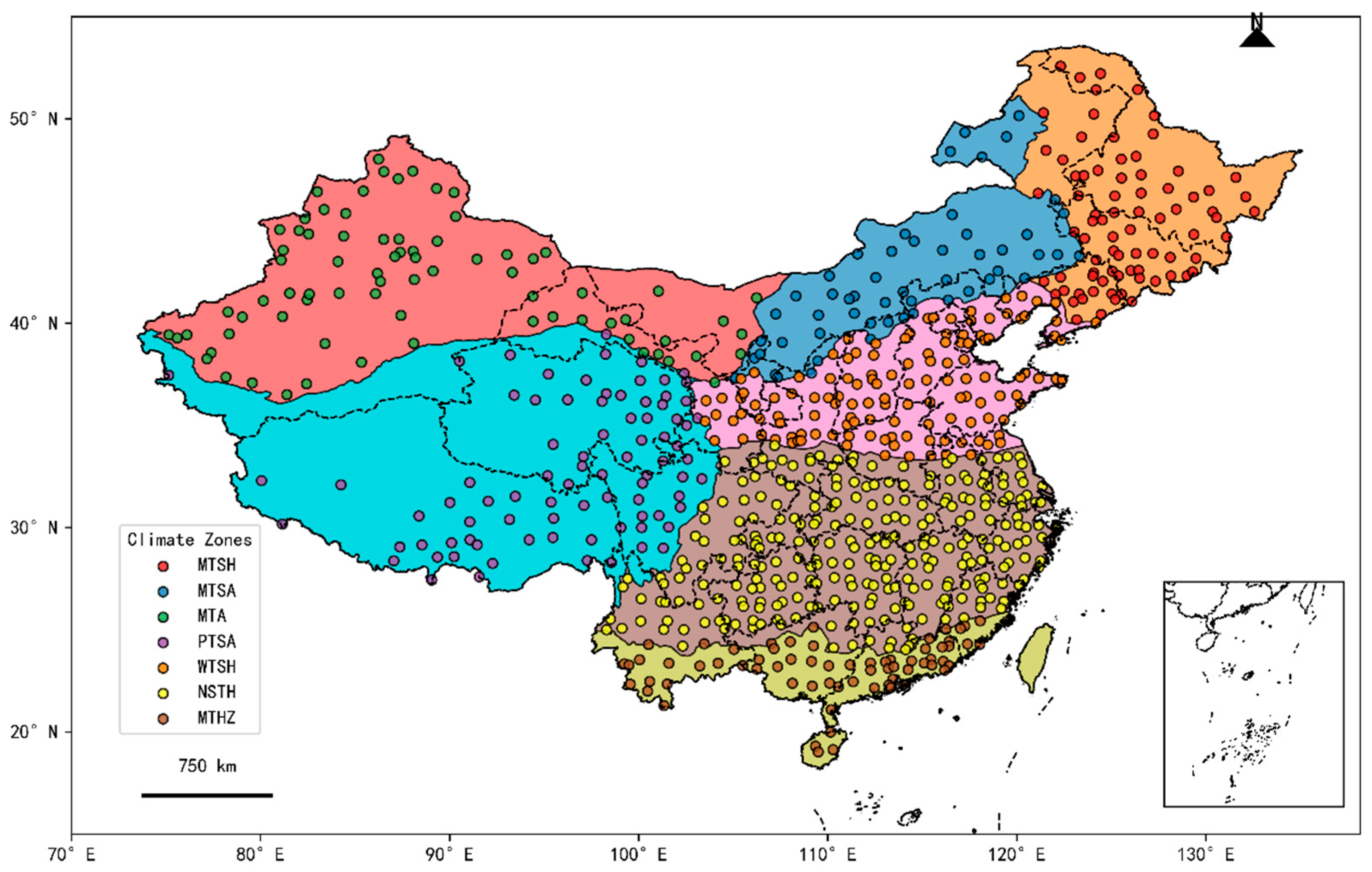

2.1. Study Area and Climate Zonation

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.4. Analytical Methods

- (1)

- Trend Analysis

- (2)

- Periodicity Analysis

- (3)

- Spatial Pattern Extraction

- (4)

- Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

- (5)

- Random Forest model and validation

3. Results

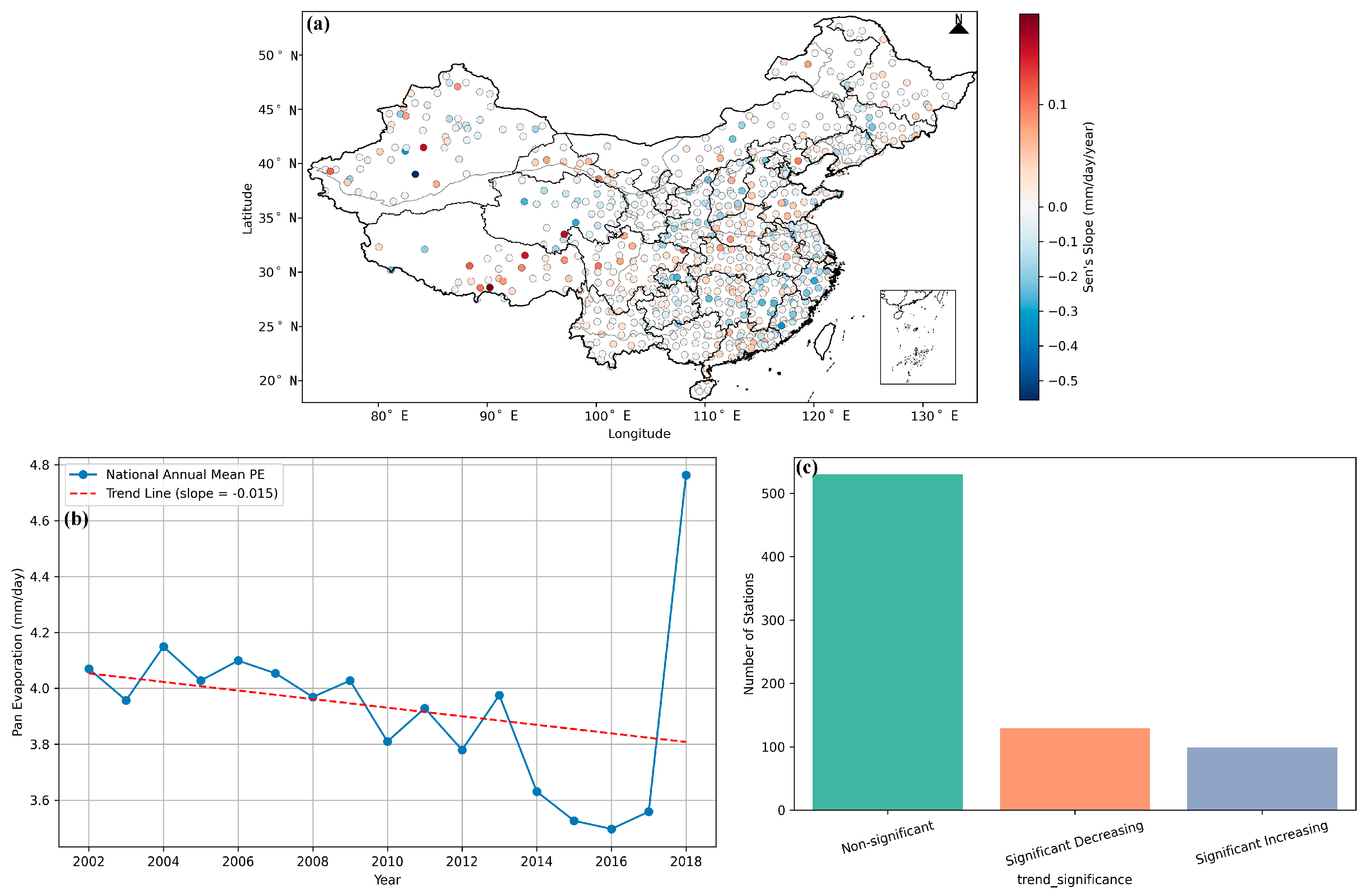

3.1. Temporal Trends of PE

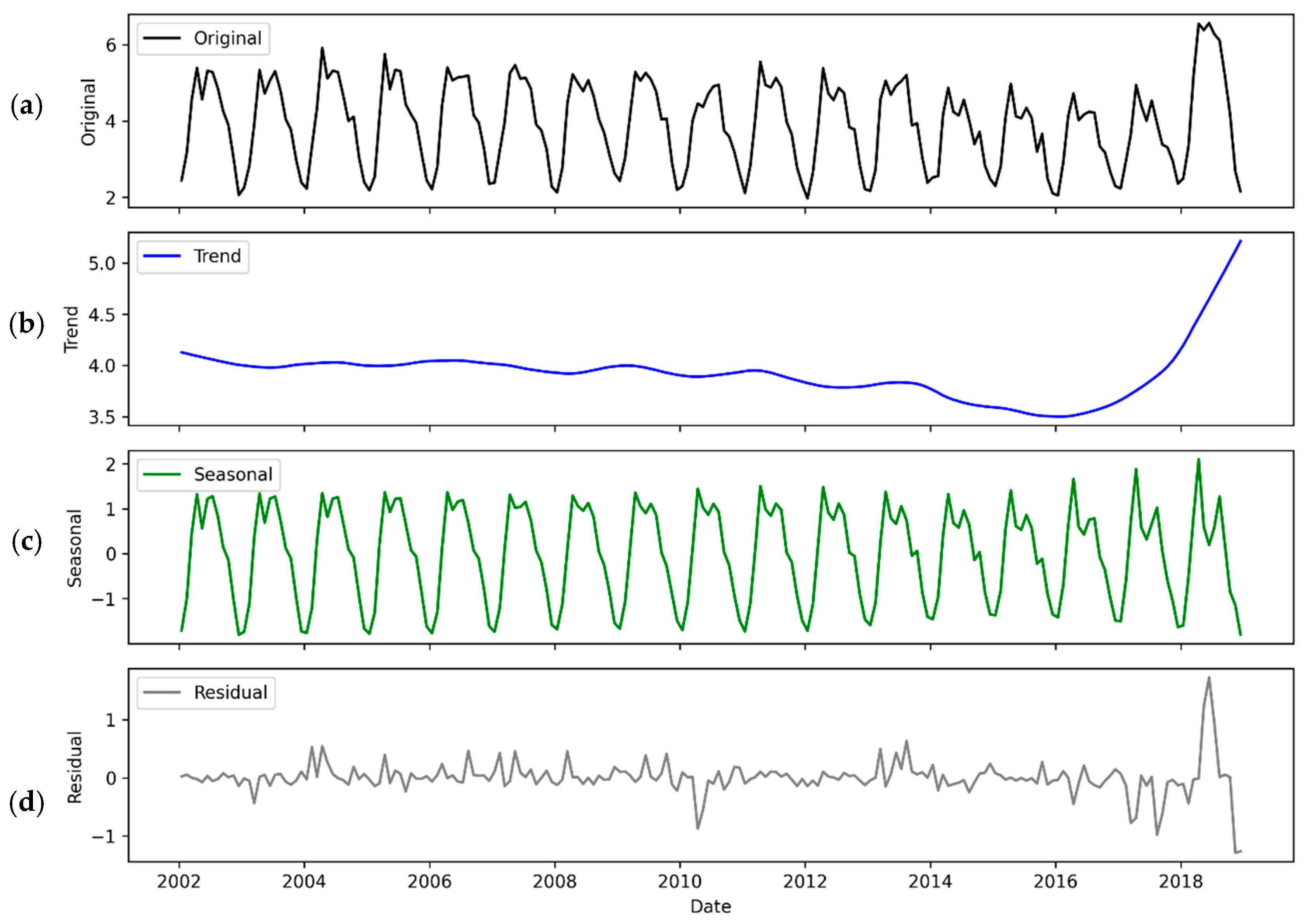

3.2. STL Decomposition of National Monthly PE

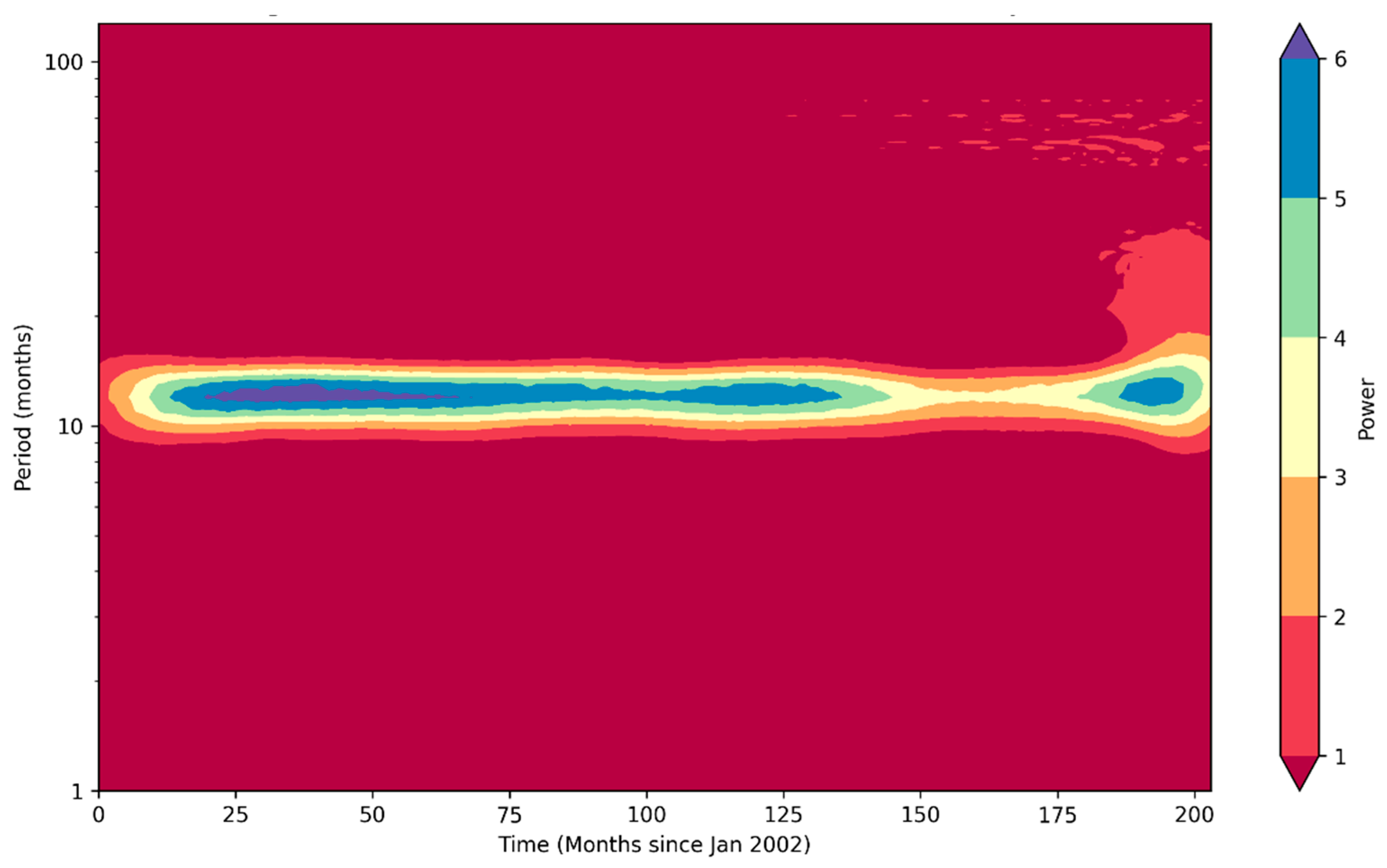

3.3. Continuous Wavelet Analysis of Monthly PE

3.4. EEMD of Monthly PE

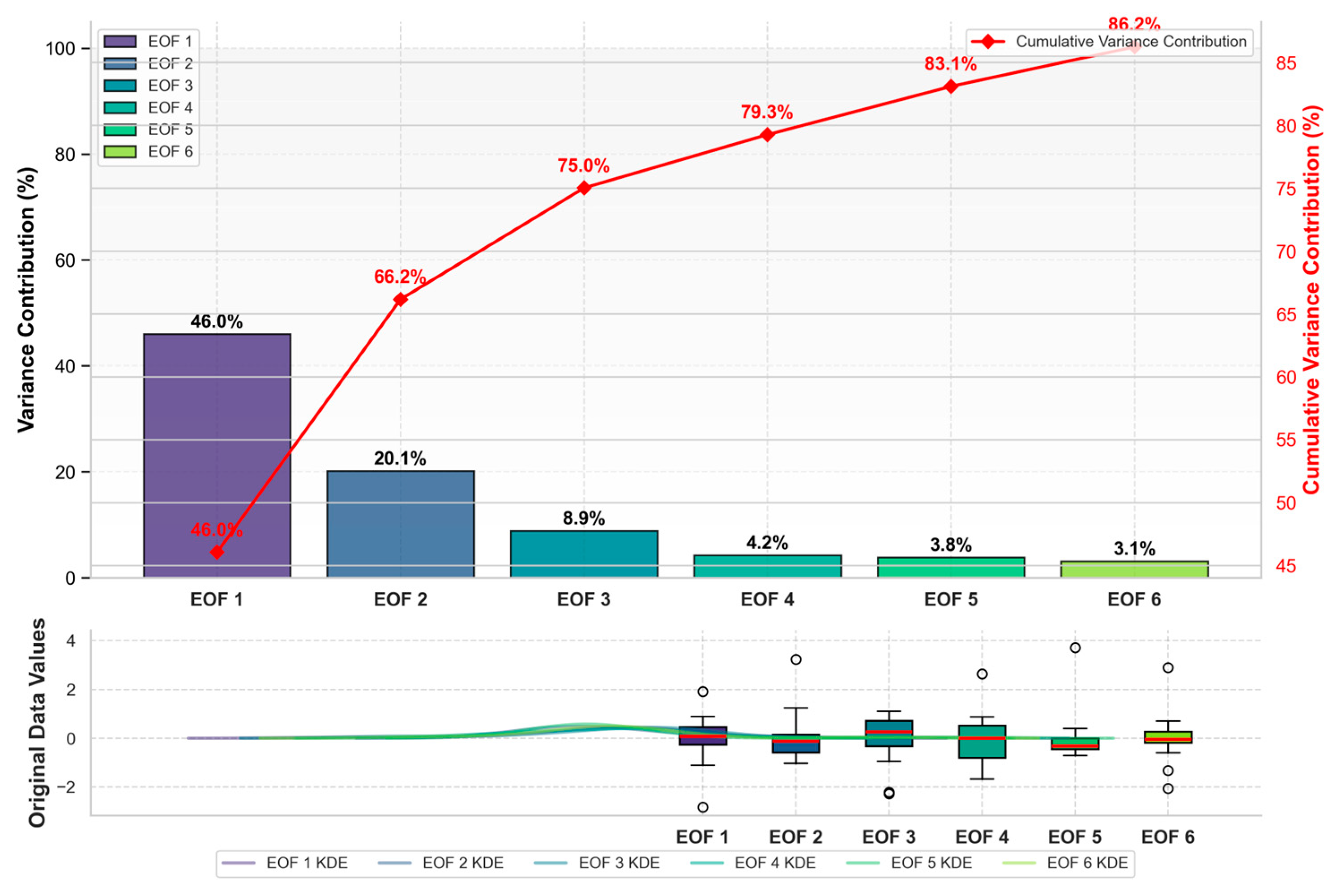

3.5. EOF Analysis

3.5.1. Variance Contribution of Leading EOF Modes

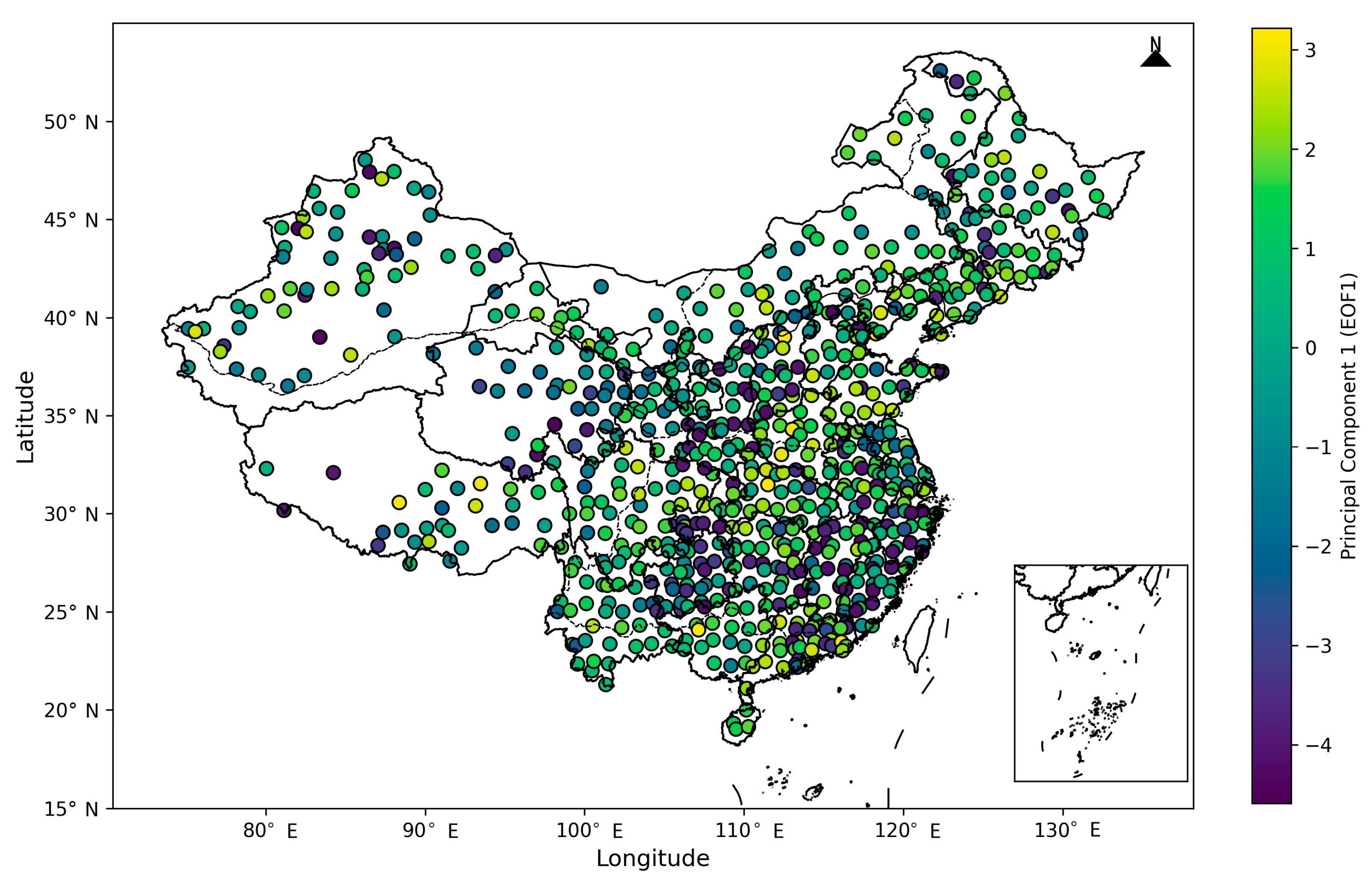

3.5.2. Spatial Distribution of EOF

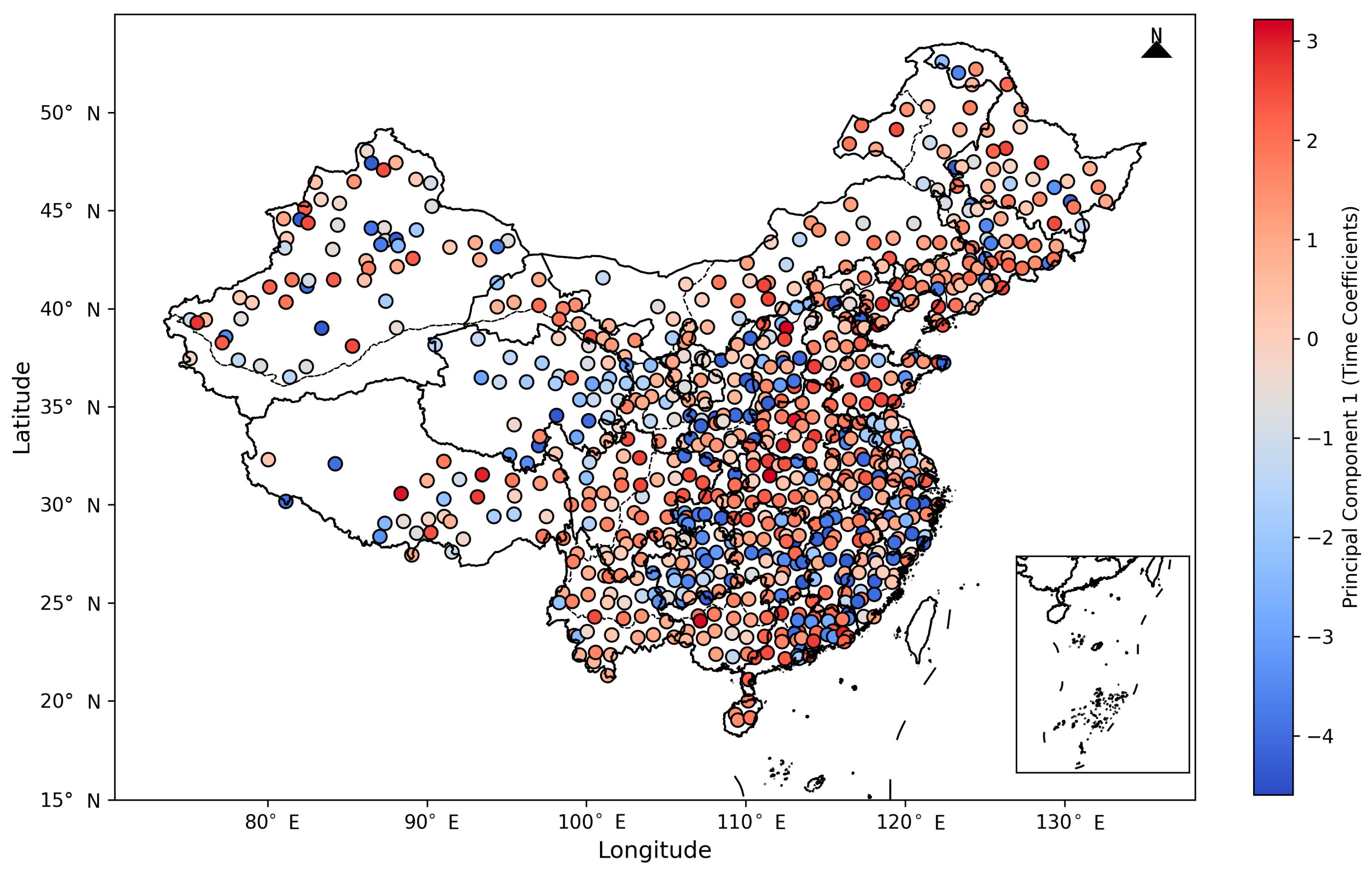

3.5.3. EOF Time Coefficient Spatial Distribution

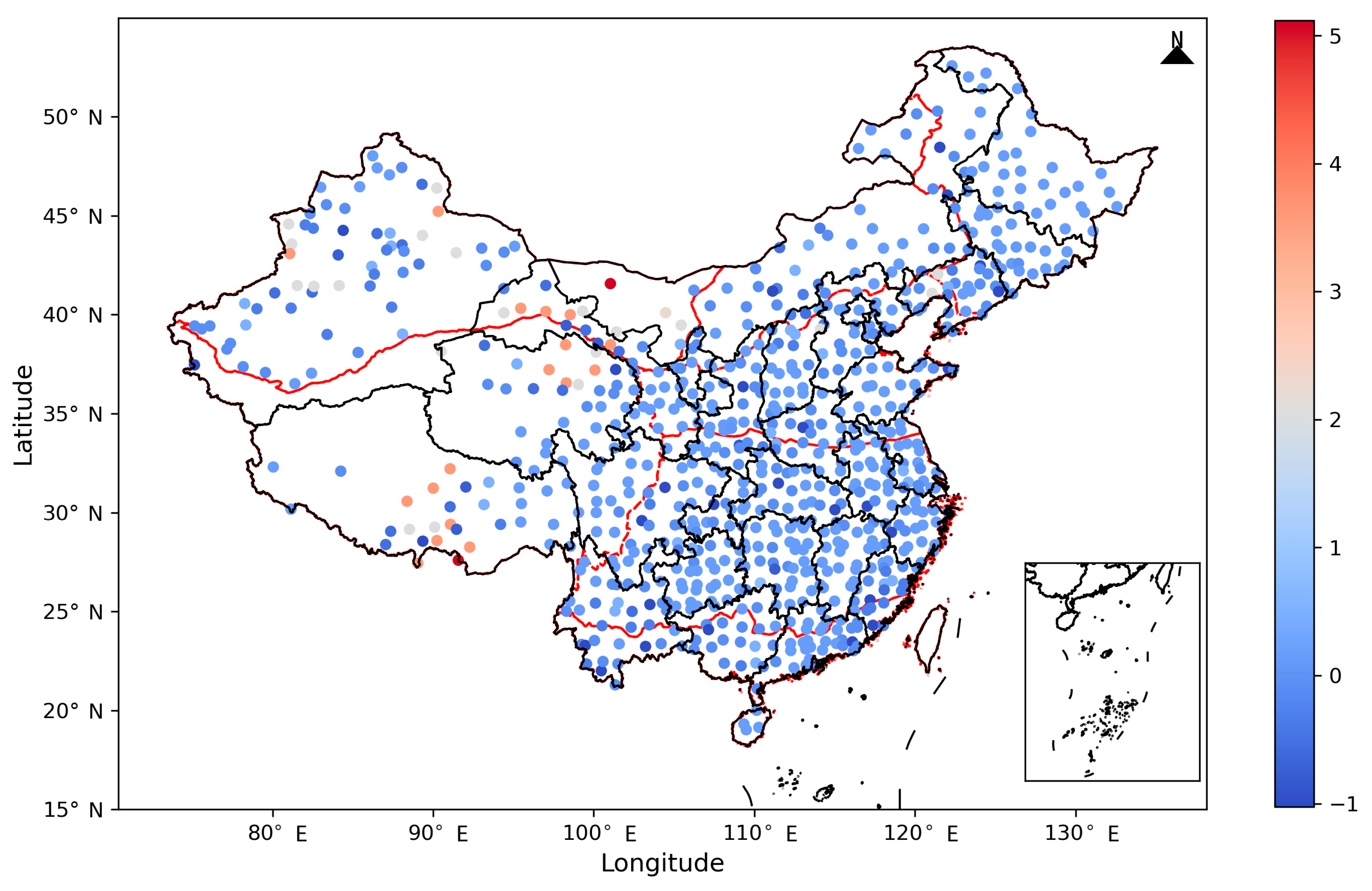

3.5.4. Spatial Distribution of Local Moran’s I for PE Values

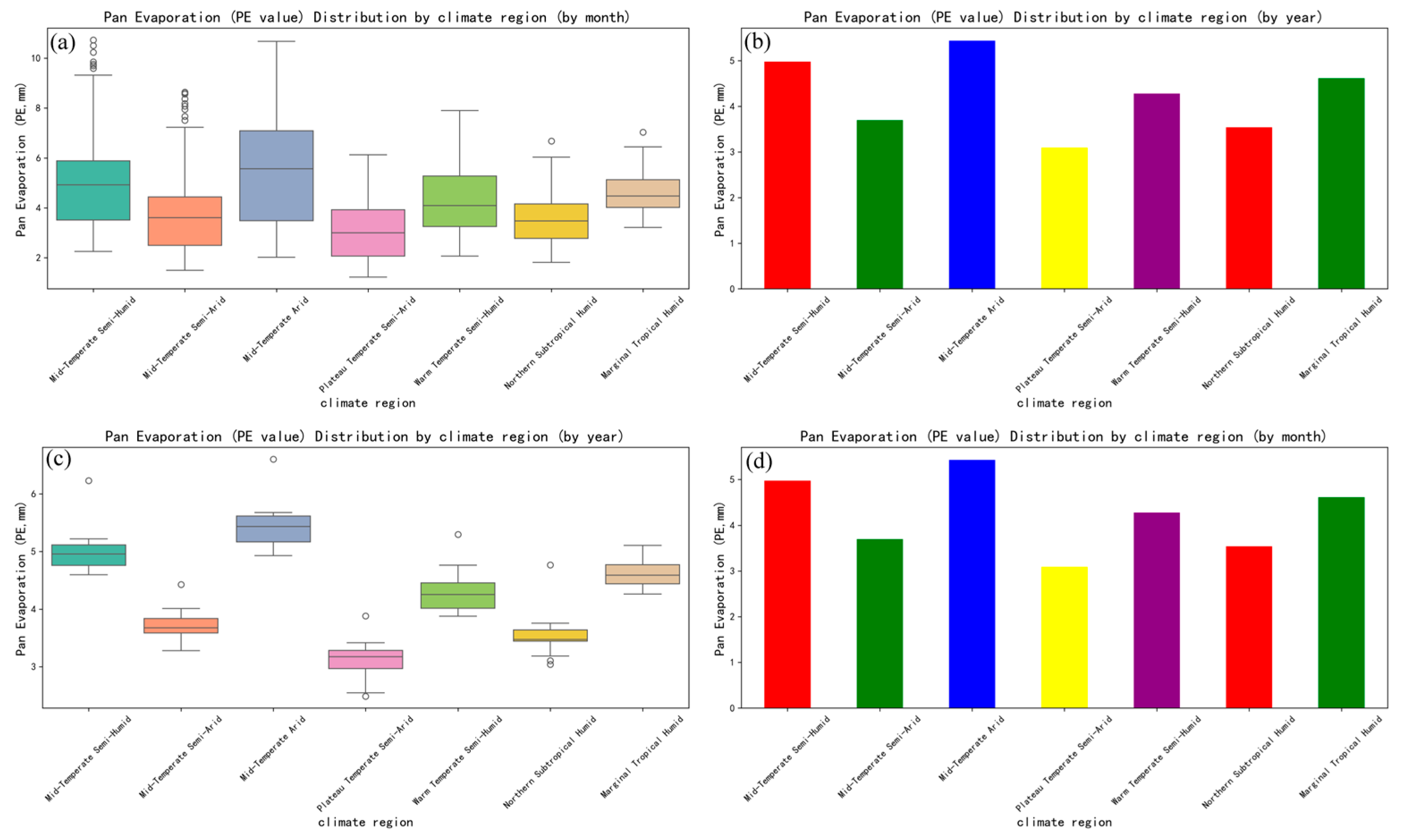

3.6. Zonal Characteristics of PE

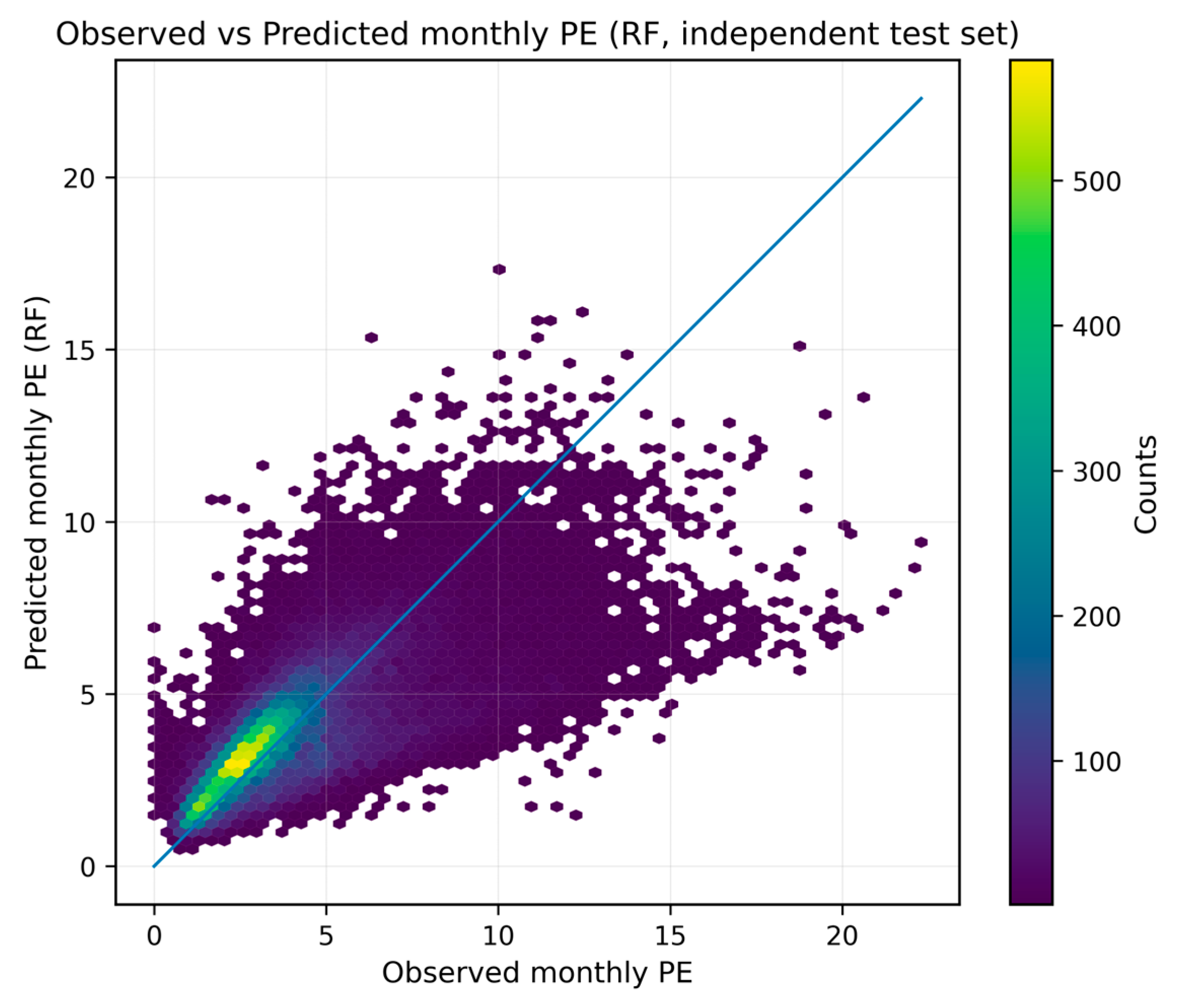

3.7. Performance Evaluation of Random Forest Model for Predicting PE

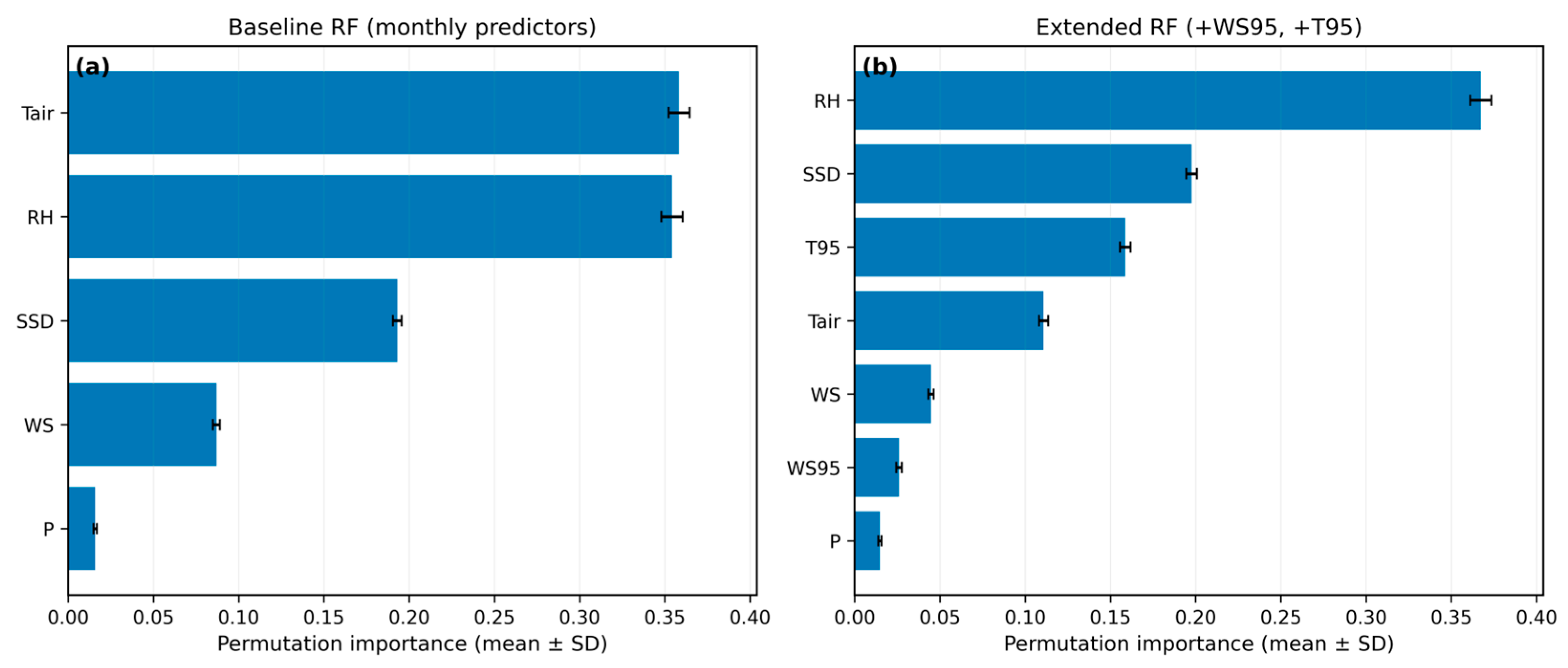

3.8. Sensitivity to Within-Month Extremes Derived from Daily Observations

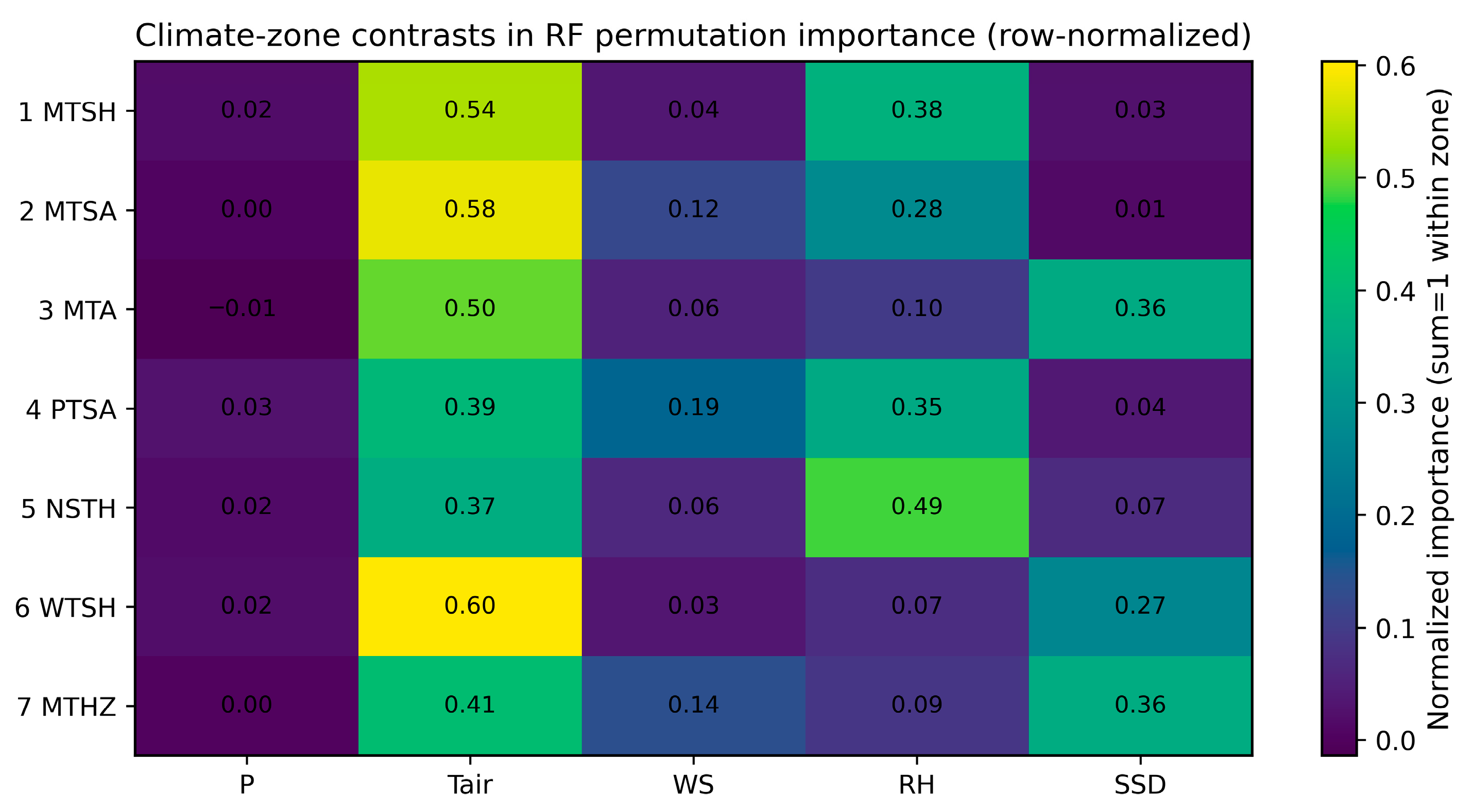

3.9. Climate-Zone RF Attribution and Model Performance

3.10. Urbanization Sensitivity Using Nighttime Lights

3.11. Meteorological Context of the 2018 PE Increase

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal Trends of PE

4.2. Climate Zone Specific Variability

4.3. Climatic Interpretation of EOF Modes and Local Spatial Autocorrelation

4.4. Meteorological Context of the 2018 PE Increase

4.5. Random Forest Model Performance

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roderick, M.L.; Rotstayn, L.D.; Farquhar, G.D.; Hobbins, M.T. On the Attribution of Changing Pan Evaporation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L17403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderick, M.L.; Farquhar, G.D. The Cause of Decreased Pan Evaporation over the Past 50 Years. Science 2002, 298, 1410–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Li, D.; Hu, Y.; Bao, Y.; Lü, S. Characteristics of Climatic Trends and Correlation between Pan-Evaporation and Environmental Factors in the Last 40 Years over China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2005, 50, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-Y.; Gong, L.; Jiang, T.; Chen, D.; Singh, V.P. Analysis of Spatial Distribution and Temporal Trend of Reference Evapotranspiration and Pan Evaporation in Changjiang (Yangtze River) Catchment. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Lu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, P.; Cheng, L. Reversed Trends in Pan and Actual Evaporation in China during 1960–2019. J. Hydrol. 2025, 653, 132810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, R.J.; Roderick, M.L.; McVicar, T.R. Can Dynamic Vegetation Information Improve the Accuracy of Budyko’s Hydrological Model? J. Hydrol. 2010, 390, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, G.; Li, P.; Mu, X. Variations of Pan Evaporation and Its Attribution from 1961 to 2015 on the Loess Plateau, China. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Feng, L. Spatiotemporal Distributions of Pan Evaporation and the Influencing Factors in China from 1961 to 2017. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 68379–68397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, F.; Wang, T.; Feng, Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, W. On the Pattern and Attribution of Pan Evaporation over China (1951–2021). J. Hydrometeorol. 2023, 24, 2023–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Charles, S.P.; Yu, J. A Critical Overview of Pan Evaporation Trends over the Last 50 Years. Clim. Change 2009, 97, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, D. Climatic Factors Influencing Changing Pan Evaporation across China from 1961 to 2001. J. Hydrol. 2012, 414–415, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, B. How Urbanization Affects Pan Evaporation in China? Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, J.J.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, X. Revealing the Response of Urban Heat Island Effect to Water Body Evaporation from Main Urban and Suburb Areas. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, D.; Cui, N. National-Scale Assessment of Pan Evaporation Models across Different Climatic Zones of China. J. Hydrol. 2018, 564, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Yu, H.; Liu, G.; Yang, R.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Effect of Urbanization on the Long-Term Change in Pan Evaporation: A Case Study of the Nanpan River Basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.M.; McVicar, T.R.; Johnson, F.M.; Marshall, L.A. Revisiting Pan Evaporation Trends in Australia a Decade On. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 11164–11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, J.J.; Dash, S.S.; McBean, E.; Wei, Y.; Li, H. Assessing the Impact of Urbanization on Urban Evapotranspiration and Its Components Using a Novel Four-Source Energy Balance Model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 316, 108853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Qin, M.; Tang, R.; Huang, X.; Hao, L.; Sun, G. Urban–Rural Interface Dominates the Effects of Urbanization on Watershed Energy and Water Balances in Southern China. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 3869–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z. Exploring the Spatial-Temporal Patterns, Drivers, and Response Strategies of Desertification in the Mu Us Desert from Multiple Regional Perspectives. Sustain 2024, 16, 9154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zou, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, J.; Liu, J.; Quan, B. Spatial-Temporal Variations of Terrestrial Evapotranspiration across China from 2000 to 2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 153951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Tian, S.; Wei, J.; Jia, S.; Song, Z. Multi-Scale Evaluation of Global Evapotranspiration Products Derived from Remote Sensing Images: Accuracy and Uncertainty. J. Hydrol. 2022, 611, 127982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezici, K.; Katipoğlu, O.M.; Şengül, S. Hybrid Machine Learning Models for Groundwater Level Prediction in a Snow-Dominated Region: An Evaluation of EEMD, VMD and EWT Decomposition Techniques. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Baetz, B. Evapotranspiration Estimation with the Budyko Framework for Canadian Watersheds. Hydrology 2024, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, E.; Mendoza Fierro, L.; Mohsenzadeh Karimi, S.; Pelak, N.; Tarouilly, E.; Chang, H.I.; Castro, C.L. Climate Change Projections of Potential Evapotranspiration for the North American Monsoon Region. Hydrology 2024, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Chen, H.; Cui, C.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Actual Evapotranspiration Changes and Their Climatic Causes in China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, P.; Lai, C.; Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal Variability of Reference Evapotranspiration and Contributing Climatic Factors in China during 1961–2013. J. Hydrol. 2017, 544, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zheng, C.; Ma, Y. Variations in Precipitation Extremes in the Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of China. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.J.; Sun, S.; Wang, M.; Li, N.; Wang, J.A.; Jin, Y.Y.; Gu, X.T.; Yin, W.X. Climate Change Regionalization in China (1961–2010). Sci. China Earth Sci. 2014, 57, 2676–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qi, T.; Li, J.; Singh, V.P.; Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal Variations of Pan Evaporation in China during 1960-2005: Changing Patterns and Causes. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, W.; Liu, W. Regionalization and Spatiotemporal Variation of Drought in China Based on Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (1961–2013). Adv. Meteorol. 2015, 2015, 950262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y.; Zheng, J. Climate Change Effects on Reference Crop Evapotranspiration across Different Climatic Zones of China during 1956–2015. J. Hydrol. 2016, 542, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Xia, J.; Luo, X.; Meng, L.; Zhang, S.; Cai, W.; Wang, W. Impacts of Climate Change-Related Flood Events in the Yangtze River Basin Based on Multi-Source Data. Atmos. Res. 2021, 263, 105819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xu, M.; Henderson, M.; Gong, W. A Spatial Analysis of Pan Evaporation Trends in China, 1955-2000. J. Geophys. Res. D Atmos. 2004, 109, D15102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.Y.; Liao, J.; Xu, B. Reconstruction of a Daily Large-Pan Evaporation Dataset over China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2012, 51, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Jin, J.; Xia, R.; Tian, S.; Yang, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, M.; Ma, T.; Jing, C.; Zhang, Y. CCAM: China Catchment Attributes and Meteorology Dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5591–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Liang, K. Spatial Patterns and Influence Factors of Conversion Coefficients between Two Typical Pan Evaporimeters in China. Water 2016, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yang, D. Revisiting the Pan Evaporation Trend in China During 1988–2017. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Hu, Q.; Qian, W. Quality Control of Daily Meteorological Data in China, 1951–2000: A New Dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 2004, 24, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolina, N.; Chang, Y.; Burningham, H. Gap Filling of Daily Weather Data Using Spatial Interpolation Techniques and Neural Network Methods. J. Coast. Res. 2024, 113, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrifa-Yamoah, E.; Mueller, U.A.; Taylor, S.M.; Fisher, A.J. Missing Data Imputation of High-Resolution Temporal Climate Time Series Data. Meteorol. Appl. 2020, 27, e1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawinkel, P.; Swinnen, E.; Lhermitte, S.; Verbist, B.; Van Orshoven, J.; Muys, B. A Time Series Processing Tool to Extract Climate-Driven Interannual Vegetation Dynamics Using Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD). Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 169, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Y. Interannual Variability of the Evaporation Duct over the South China Sea and Its Relations with Regional Evaporation. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2017, 122, 6698–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliengchuay, W.; Mingkhwan, R.; Kiangkoo, N.; Suwanmanee, S.; Sahanavin, N.; Kongpran, J.; Aung, H.W.; Tantrakarnapa, K. Analyzing Temperature, Humidity, and Precipitation Trends in Six Regions of Thailand Using Innovative Trend Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jin, J. Analysis of Water Yield Changes from 1981 to 2018 Using an Improved Mann-Kendall Test. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, J.; Jiang, W. Variation in Reference Evapotranspiration over the Tibetan Plateau during 1961–2017: Spatiotemporal Variations, Future Trends and Links to Other Climatic Factors. Water 2020, 12, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Zhao, K.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Quantifying the Spatio-Temporal Variations and Impacts of Factors on Vegetation Water Use Efficiency Using STL Decomposition and Geodetector Method. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition: A Noise-Assisted Data Analysis Method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 1, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, R.B.; Cleveland, W.S.; McRae, J.E.; Terpenning, I. STL: A Seasonal-Trend Decomposition. J. Off. Stat. 1990, 6, 3–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, A.; Jolliffe, I.T.; Stephenson, D.B. Empirical Orthogonal Functions and Related Techniques in Atmospheric Science: A Review. Int. J. Climatol. 2007, 27, 1119–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollife, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, C. Identification of Dominant Climate Factor for Pan Evaporation Trend in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z.M.; Al-Juboori, A.M.; Beyaztas, U.; Al-Ansari, N.; Chau, K.W.; Qi, C.; Ali, M.; Salih, S.Q.; Shahid, S. Prediction of Evaporation in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions: A Comparative Study Using Different Machine Learning Models. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2020, 14, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kisi, O.; Hu, B.; Bilal, M.; Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Li, H. Evaporation Modelling Using Different Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | R2 | MSE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.493 | 3.159 | 1.777 |

| Linear Regression | 0.429 | 3.559 | 1.886 |

| Ridge Regression (alpha = 100.0) | 0.429 | 3.559 | 1.887 |

| Model | R2 | MSE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (monthly predictors) [subset n_days ≥ 25] | 0.494 | 3.158 | 1.775 |

| Extended (+WS95 +T95) [subset n_days ≥ 25] | 0.503 | 3.097 | 1.759 |

| Climate_Zone | Stations | Station_Months | R2 | MSE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTSH | 79 | 16,020 | 0.577 | 2.267 | 1.506 |

| MTSA | 53 | 10,740 | 0.446 | 3.724 | 1.930 |

| MTA | 77 | 15,180 | 0.355 | 5.426 | 2.329 |

| PTSA | 84 | 16,872 | 0.183 | 2.899 | 1.703 |

| NSTH | 129 | 26,160 | 0.367 | 3.139 | 1.772 |

| WTSH | 270 | 54,790 | 0.423 | 2.250 | 1.500 |

| MTHZ | 67 | 13,572 | 0.186 | 2.762 | 1.662 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Li, X. Atmospheric Drivers and Spatiotemporal Variability of Pan Evaporation Across China (2002–2018). Atmosphere 2026, 17, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010073

Li S, Li X. Atmospheric Drivers and Spatiotemporal Variability of Pan Evaporation Across China (2002–2018). Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shuai, and Xiang Li. 2026. "Atmospheric Drivers and Spatiotemporal Variability of Pan Evaporation Across China (2002–2018)" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010073

APA StyleLi, S., & Li, X. (2026). Atmospheric Drivers and Spatiotemporal Variability of Pan Evaporation Across China (2002–2018). Atmosphere, 17(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010073