Assessment of Vertical Wind Characteristics for Wind Energy Utilization and Carbon Emission Reduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

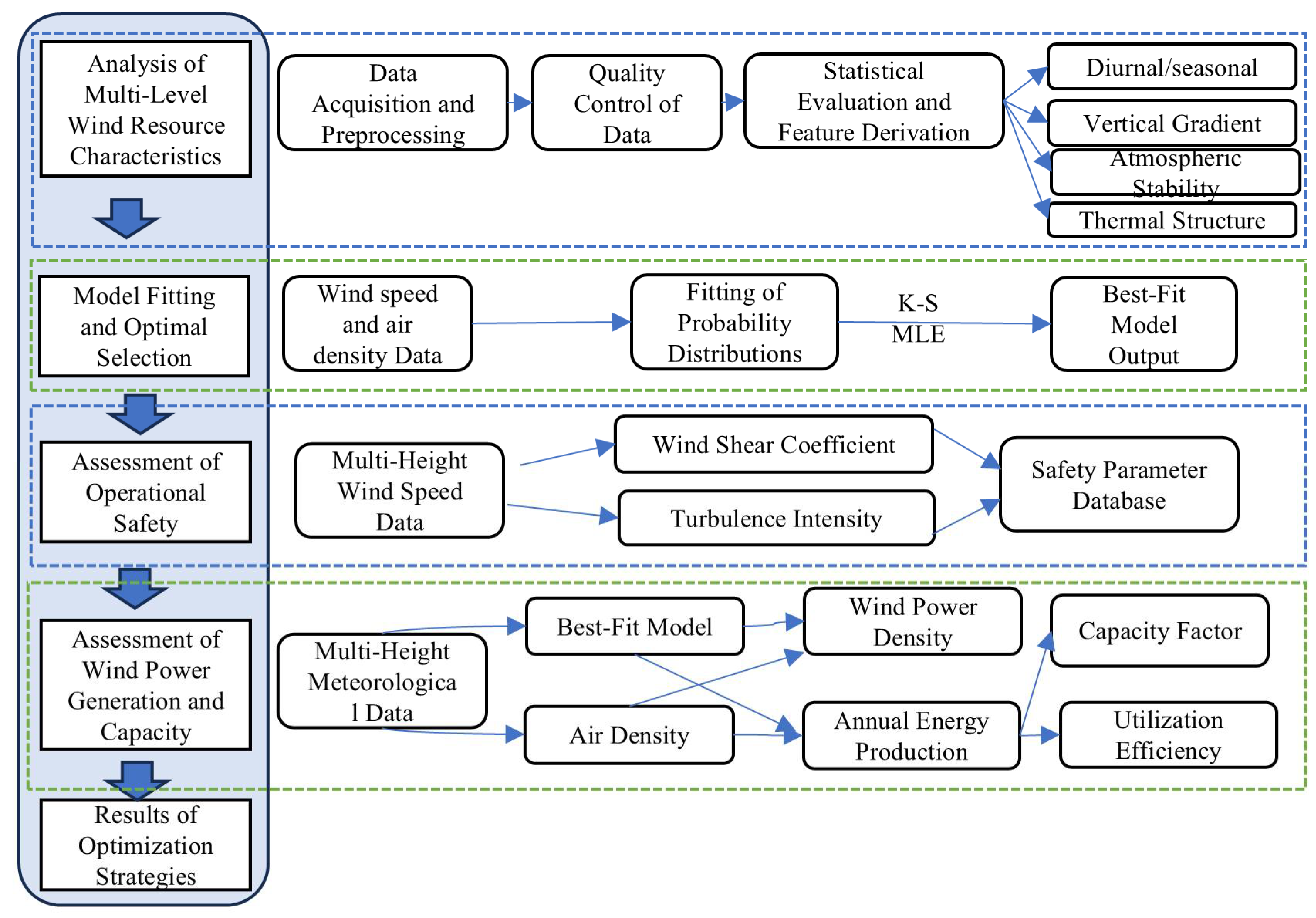

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

- (1)

- Removal of stagnant values: In the time series, if a measurement remains unchanged for a prolonged period, it usually indicates sensor malfunction, signal transmission failure, or operational faults of the instrument. These constant readings are defined as stagnant (or frozen) values. Data points that deviate from the stagnant value by more than 0.5 are identified, and the segment from the onset of the stagnant value up to the point immediately before the deviation is discarded.

- (2)

- Elimination of outliers: Based on historical climatic statistics of the study area, wind speeds greater than 50 m/s are considered unrealistic and directly excluded. For temperature data, acceptable ranges are defined by season: −23 to 25 °C (January–March), −5 to 45 °C (April–June), 0 to 50 °C (July–September), and −20 to 30 °C (October–December). Measurements falling outside these ranges are regarded as outliers and removed.

- (3)

- Temporal continuity control: For each data point, the difference between its value and the weighted average of the four consecutive neighboring points is calculated. If the difference exceeds the specified threshold (5 m/s for wind speed and 4 °C for temperature), the point is deemed discontinuous. Such values are replaced using the four-point central interpolation method, with the interpolated value computed from the weighted average.

- (4)

- Spatial continuity control: When outliers cannot be corrected using the four-point central interpolation method, the spatial continuity of the measurements is employed. Specifically, if valid data from other heights are available at the same time step, spline interpolation based on the surrounding height levels is applied to estimate and replace the missing or erroneous value.

2.2. Method

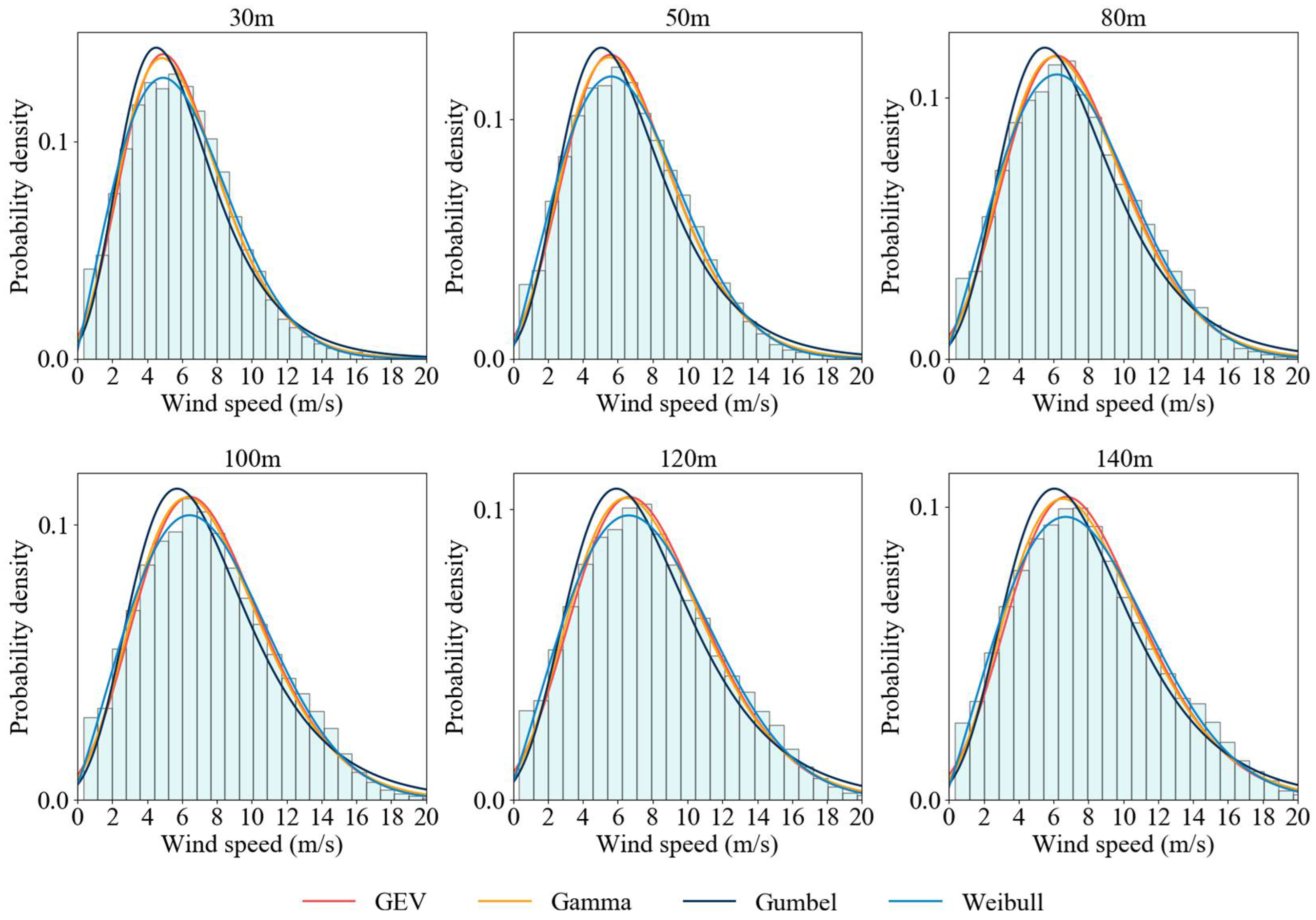

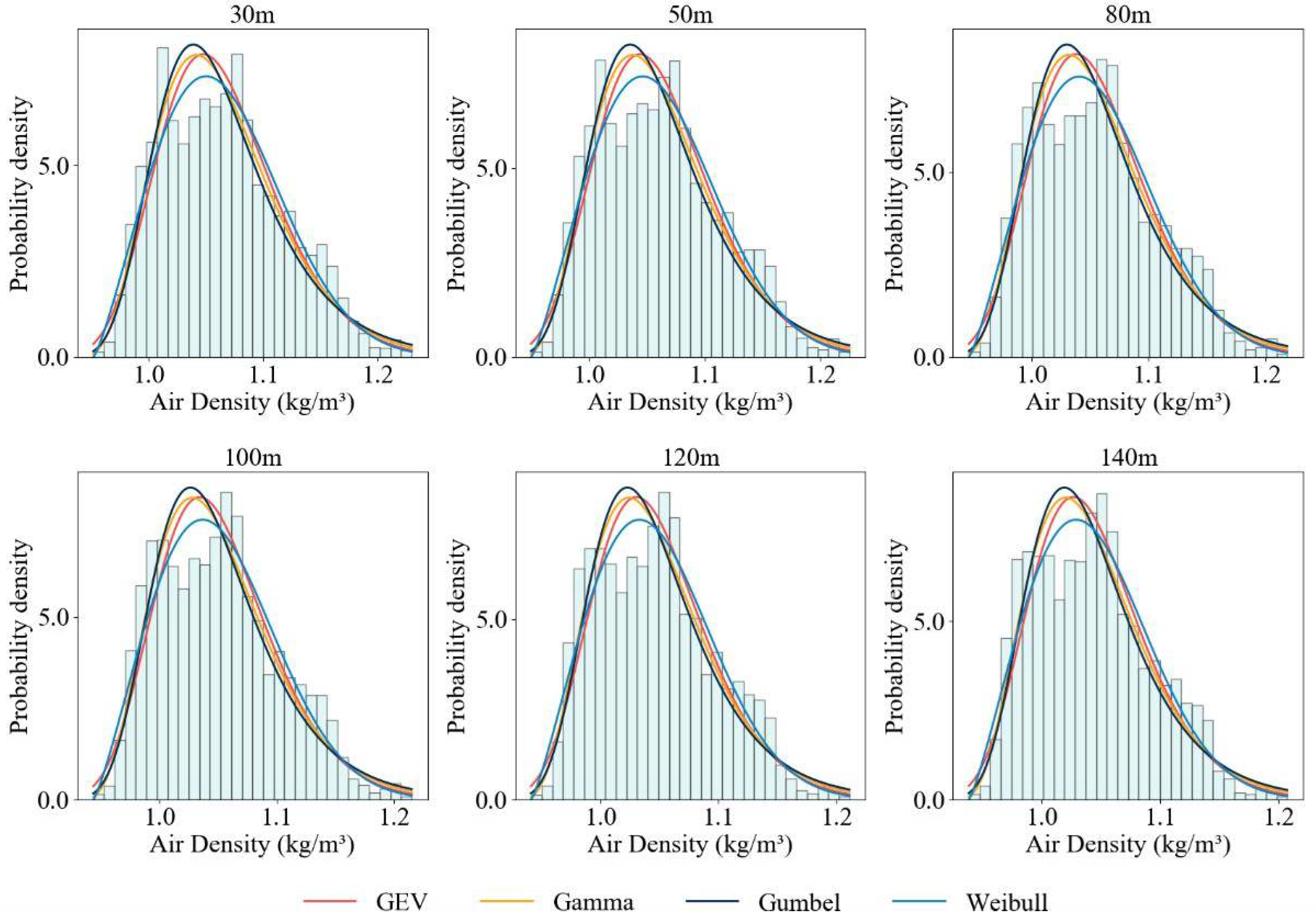

2.2.1. Multi-Level Wind Resource Characteristics and Model Fitting

2.2.2. Operational Security Assessment

2.2.3. Wind Farm Power and Capacity Evaluation

2.2.4. Estimation of Carbon Emission Reductions

3. Results and Discussion

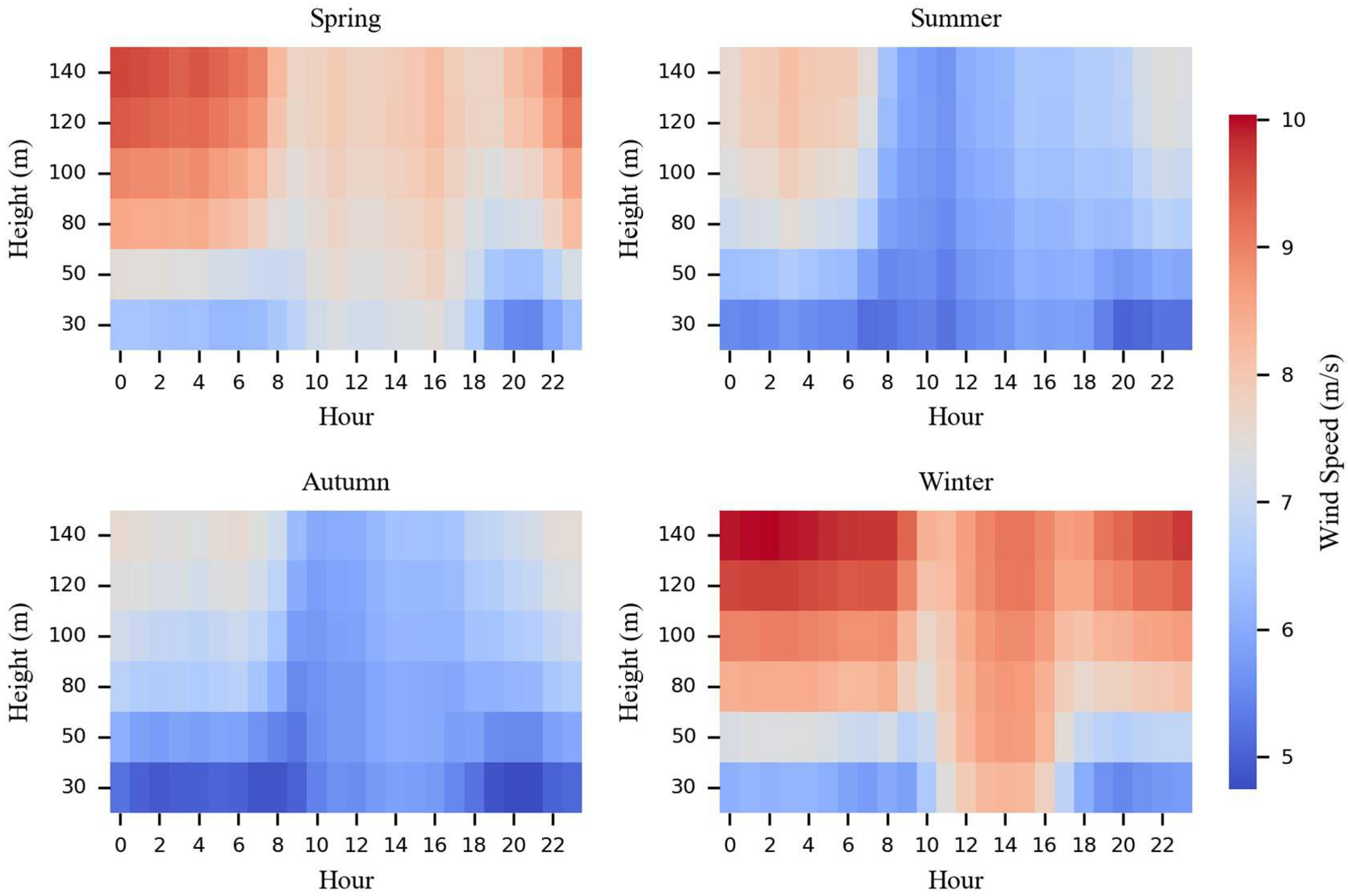

3.1. Wind Speed Characteristics

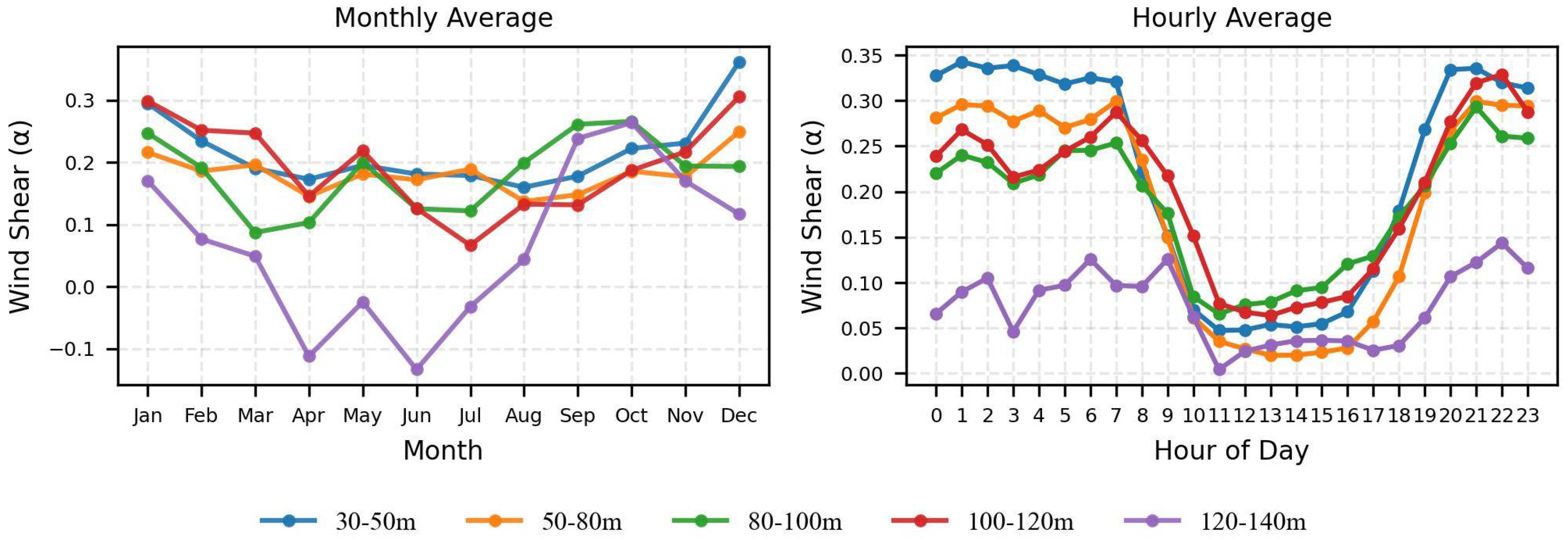

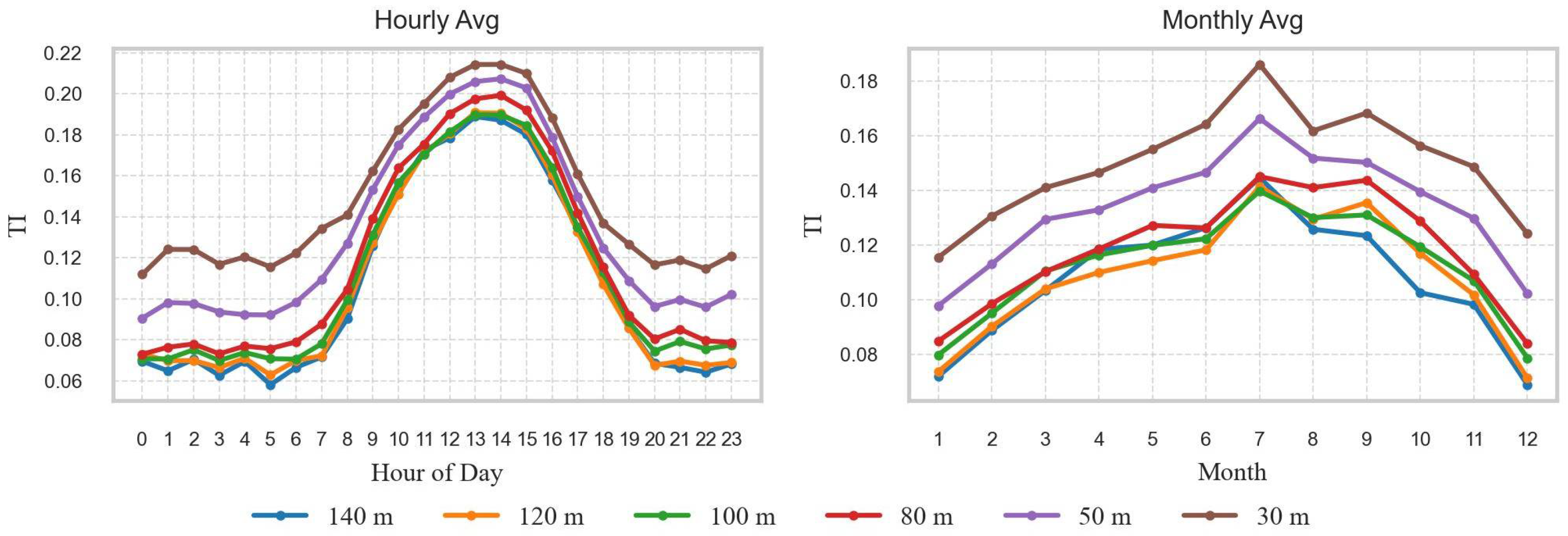

3.2. Vertical Wind Profile and Turbulence Analysis

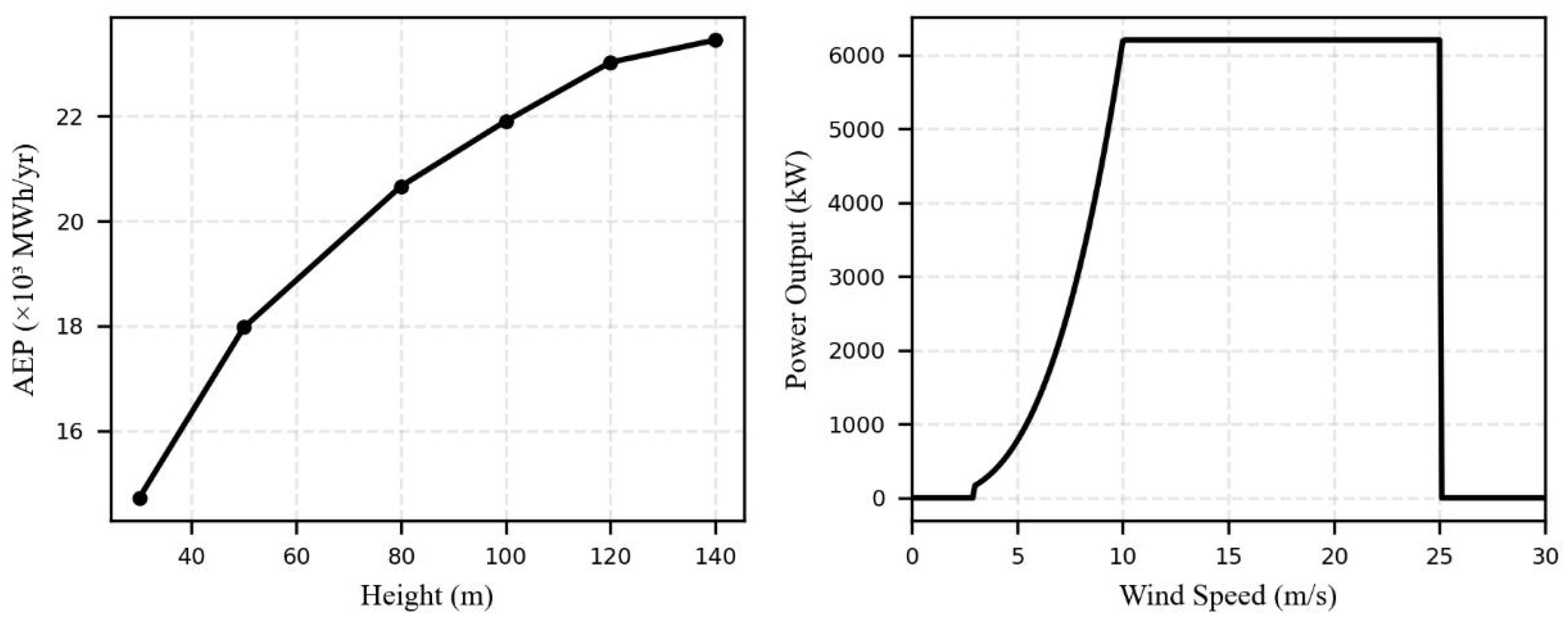

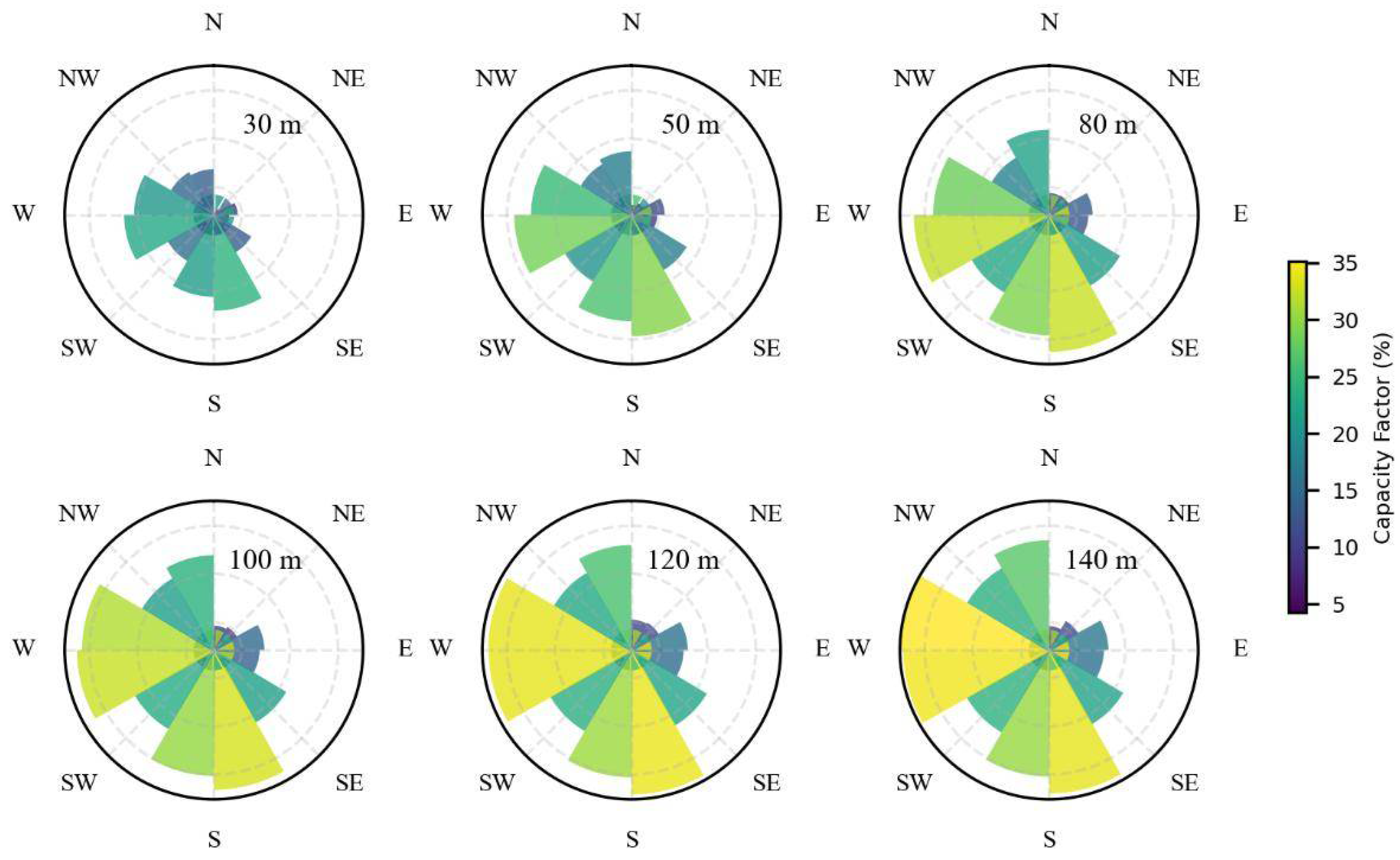

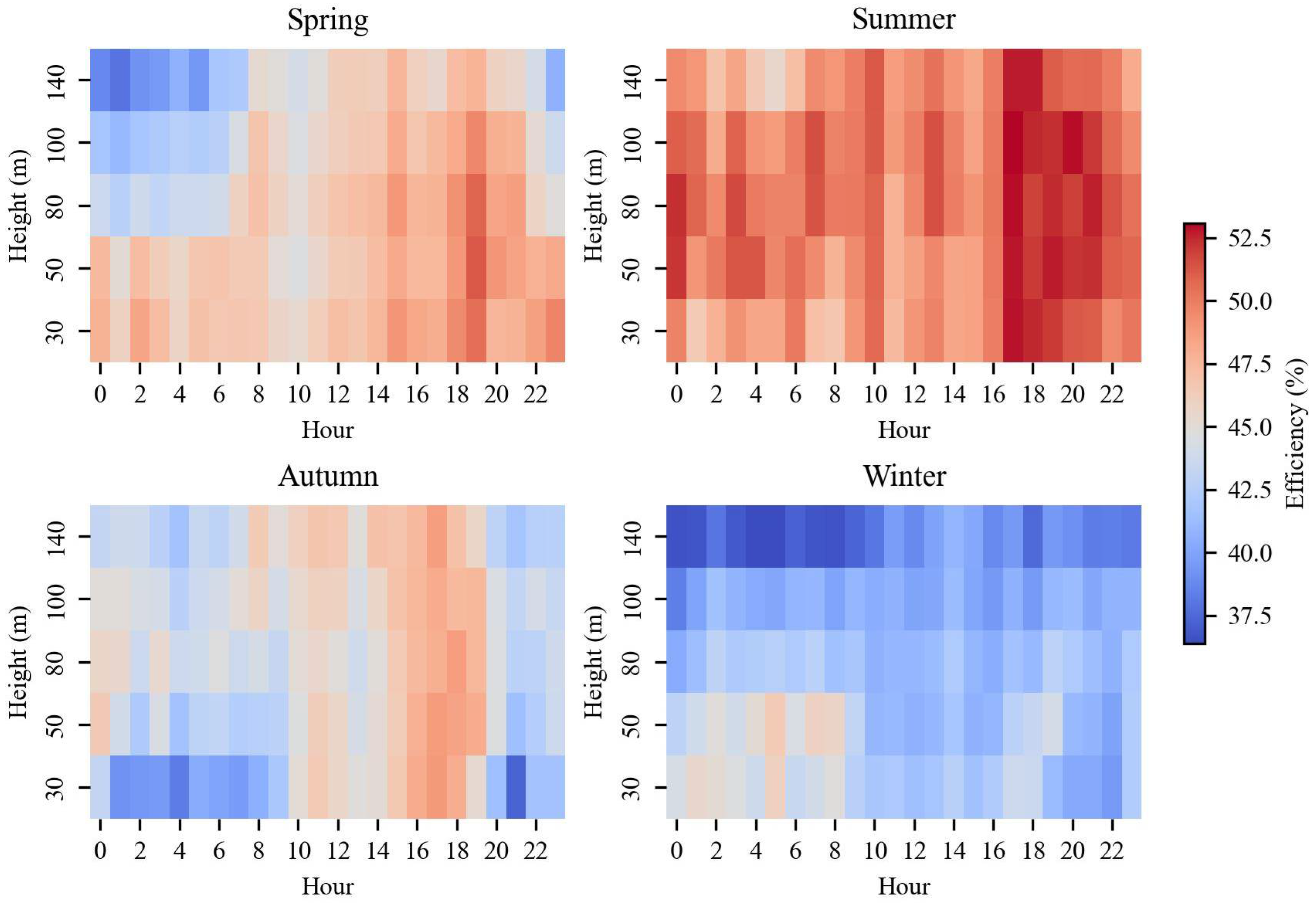

3.3. Performance Evaluation of Wind Power Utilization

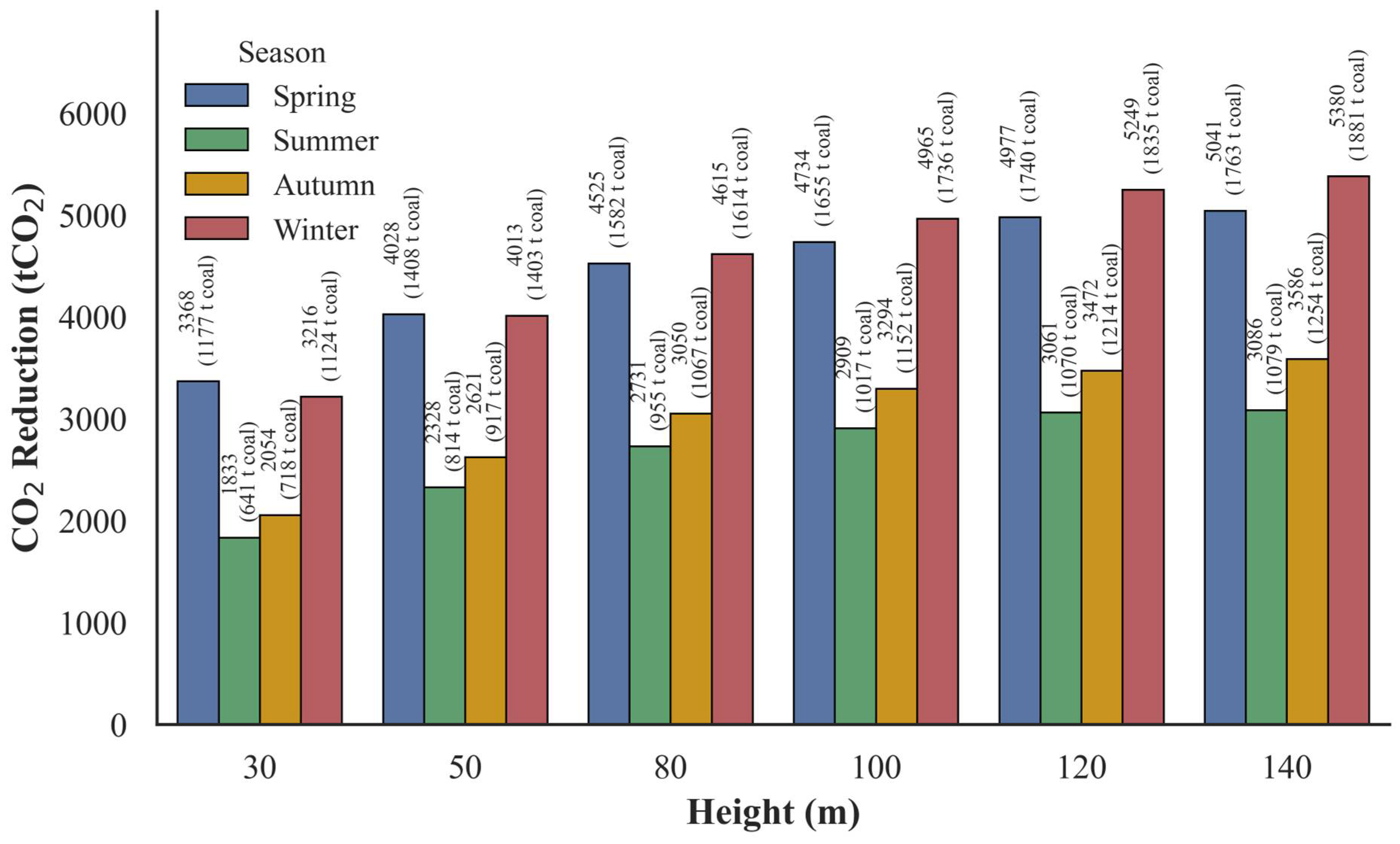

3.4. Carbon Emission Reduction Potential

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomas, B.; Costoya, X.; DeCastro, M.; Insua-Costa, D.; Senande-Rivera, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Downscaling CMIP6 climate projections to classify the future offshore wind energy resource in the Spanish territorial waters. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 433, 139860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qi, W.; Guo, P.; Li, J. Power prediction of a Savonius wind turbine cluster considering wind direction characteristics on three sites. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.; Nian, H.; Fan, W. Research on Evaluation Method of Wind Farm Wake Energy Efficiency Loss Based on SCADA Data Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, K.S.R.; Rahi, O.P. A comprehensive review of wind resource assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 1320–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouerghi, F.H.; Omri, M.; Menaem, A.A.; Taloba, A.I.; Abd El-Aziz, R.M. Feasibility evaluation of wind energy as a sustainable energy resource. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 106, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. China Hit New Record of Solar and Wind Power Capacity Additions in 2024; Climate Energy Finance location: Sydney, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, B.; Ma, Z.; Geng, Y.; Heck, P.; Ren, W.; Tobias, M.; Maas, A.; Jiang, P.; Puppim De Oliveira, J.A.; Fujita, T. A life cycle co-benefits assessment of wind power in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. Global trends of wind direction-dependent wind resource. Energy 2024, 304, 132235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelser, T.; Weinand, J.M.; Kuckertz, P.; McKenna, R.; Linssen, J.; Stolten, D. Reviewing accuracy & reproducibility of large-scale wind resource assessments. Adv. Appl. Energy 2024, 13, 100158. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, F.; Yalcin, M. Investigation of the importance of criteria in potential wind farm sites via machine learning algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Varum, C.; Botelho, A. Wind power and CO2 emissions in the Irish market. Energy Econ. 2019, 80, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Sun, L.; Wang, J. Monthly variation and correlation analysis of global temperature and wind resources under climate change. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 285, 116992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, B.; Yan, N.; Zhu, W.; Zeng, H.; Ma, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, X.; Pang, B. Quantifying the Contributions of Environmental Factors to Wind Characteristics over 2000–2019 in China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, R.; Ma, M. Research on ultra-short term forecasting technology of wind power output based on various meteorological factors. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafei, B.; Popov, A.; Giddings, D. Enhanced offshore wind resource assessment using hybrid data fusion and numerical models. Energy 2024, 310, 133208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhong, S.; Shen, L.; Li, D.; Zhao, J.; Hou, X. From potential to utilization: Exploring the optimal layout with the technical path of wind resource development in Tibet. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 304, 118231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta-Prieto, M.E.; Schell, K.R. Data-driven optimization for wind farm siting. Int. J. Electr. Power 2024, 155, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, K.K.; Cater, J.E.; Kingan, M.J.; Bellon, G.D.; Sharma, R.N. Wind resource assessment and energy potential of selected locations in Fiji. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, C.Y.; Ren, J.; Gao, Z.; Liang, H.; Wang, L. Wind resource potential assessment using a long term tower measurement approach: A case study of Beijing in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floors, R.; Nielsen, M. Estimating Air Density Using Observations and Re-Analysis Outputs for Wind Energy Purposes. Energies 2019, 12, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, C.; Ji, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Qin, Z. Estimation of the influences of spatiotemporal variations in air density on wind energy assessment in China based on deep neural network. Energy 2022, 239, 122210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulazia, A.; Sáenz, J.; Ibarra-Berastegi, G.; González-Rojí, S.J.; Carreno-Madinabeitia, S. Global estimations of wind energy potential considering seasonal air density changes. Energy 2019, 187, 115938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. Introducing a new approach for wind energy potential assessment under climate change at the wind turbine scale. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 225, 113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B. Changes in wind turbine power characteristics and annual energy production due to atmospheric stability, turbulence intensity, and wind shear. Energy 2021, 214, 119051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.H.; Wen, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y.; Yang, A.S. Numerical assessments of wind power potential and installation arrangements in realistic highly urbanized areas. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D.; Laible, J.; Buchholz, A. Introducing a system of wind speed distributions for modeling properties of wind speed regimes around the world. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 144, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Tan, Y.; Yang, W.; Wen, L.; Shen, X. Investigation of wind resource characteristics in mountain wind farm using multiple-unit SCADA data in Chenzhou: A case study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 148, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, W.; Xiong, X. Generation System Reliability Evaluation Incorporating Correlations of Wind Speeds With Different Distributions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.; Ni, G.; Yang, H.; Lei, Z. Numerical Analysis on the Contribution of Urbanization to Wind Stilling: An Example over the Greater Beijing Metropolitan Area. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2013, 52, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ji, X.D.; Yang, S.H.; Zhang, Z.Y. Assessment of wind resource potential at different heights in urban areas: A case study of Beijing. Renew. Energy 2025, 248, 123175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.Y.; Chan, P.W.; Li, Q.S.; Huang, T.; Yim, S.H.L. Assessment of urban wind energy resource in Hong Kong based on multi-instrument observations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo Díaz, A.; Herrera Moya, I.; Castellanos, J.E.; Garabitos Lara, E. Optimal Positioning of Small Wind Turbines Into a Building Using On-Site Measurements and Computational Fluid Dynamic Simulation. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2024, 146, 081801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Sander, L.; Schindler, D. Future global offshore wind energy under climate change and advanced wind turbine technology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, B. Capacity expansion model for multi-temporal energy storage in renewable energy base considering various transmission utilization rates. J. Energy Storage 2024, 98, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Fan, X.; He, Y. Comprehensive evaluation index system for wind power utilization levels in wind farms in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelletti, M.; Raimondo, D.M.; De Nicolao, G. Wind power curve modeling: A probabilistic Beta regression approach. Renew. Energy 2024, 223, 119970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Han, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J. A multivariable wind turbine power curve modeling method considering segment control differences and short-time self-dependence. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Z.; Heidari, A.A.; Chen, H.; Liang, G. Dual-weight decay mechanism and Nelder-Mead simplex boosted RIME algorithm for optimal power flow. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Hu, Y.; Fang, F.; Yao, L.; Liu, J. Wind farm power production and fatigue load optimization based on dynamic partitioning and wake redirection of wind turbines. Appl. Energy 2023, 339, 121000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, S.; Ma, Y.; Ling, Z.; Luo, Q. Combined wake control of aligned wind turbines for power optimization based on a 3D wake model considering secondary wake steering. Energy 2024, 308, 132900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Li, S.; Shangguan, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, H. Analysis of Wind Turbine Equipment Failure and Intelligent Operation and Maintenance Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howland, M.F.; Quesada, J.B.; Martínez, J.J.P.; Larrañaga, F.P.; Yadav, N.; Chawla, J.S.; Sivaram, V.; Dabiri, J.O. Collective wind farm operation based on a predictive model increases utility-scale energy production. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Pei, J.; Xu, D.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Coordinated control of a hybrid wind farm with DFIG-based and PMSG-based wind power generation systems under asymmetrical grid faults. Renew. Energy 2018, 127, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, H.S.; Deb, D. Wake management based life enhancement of battery energy storage system for hybrid wind farms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 130, 109912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Z. A holistic robust method for optimizing multi-timescale operations of a wind farm with energy storages. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Choi, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, Y.H. Understanding the Characteristics of Vertical Structures for Wind Speed Observations via Wind-LIDAR on Jeju Island. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, A.; Sillmann, J.; Vigo, I. Better seasonal forecasts for the renewable energy industry. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, S.; Jin, S.; Wu, J. Estimation methods review and analysis of offshore extreme wind speeds and wind energy resources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ji, X.; Tao, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L. Study on Non-Stationary Wind Speed Models and Wind Load Design Parameters Based on Data from the Beijing 325 m Meteorological Tower, 1991–2020. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, C.; Ji, X.; Xue, X.; Jiang, L.; Yang, S. Joint Probability Distribution of Extreme Wind Speed and Air Density Based on the Copula Function to Evaluate Basic Wind Pressure. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, C.G. Revisiting the Use of the Gumbel Distribution: A Comprehensive Statistical Analysis Regarding Modeling Extremes and Rare Events. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.P. Estimation of wind energy potential using different probability density functions. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. The role of air density in wind energy assessment—A case study from Germany. Energy 2019, 171, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Xue, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Ji, X. China’s future wind energy considering air density during climate change. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J. Potential capacity factor estimates of wind generating resources for transmission planning. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, D. Untangling global levelised cost of electricity based on multi-factor learning curve for renewable energy: Wind, solar, geothermal, hydropower and bioenergy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Farnham, D.J.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lewis, N.S.; Caldeira, K.; Davis, S.J. Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Han, M.; Chen, L.; Ai, C.; Liu, S.; Cao, S.; Wei, L. Life cycle carbon emission accounting of a typical coastal wind power generation project in Hebei Province, China. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 324, 119243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Sun, L. Investigation of the vertically-layered structure and surface roughness parameters of the urban boundary layer. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2023, 32, e2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Dickinson, R. Increase in Surface Friction Dominates the Observed Surface Wind Speed Decline during 1973–2014 in the Northern Hemisphere Lands. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 7421–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, A.; Bernalte Jimenez, B.; Gross, G.; Wulff, D.; Kenull, T. One-year observations of the wind distribution and low-level jet occurrence at Braunschweig, North German Plain. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Mamtimin, A.; Yang, F.; Huo, W.; Wang, M.; Pan, H.; He, Q.; Jin, L.; Yang, X. Dust uplift potential in the Taklimakan Desert: An analysis based on different wind speed measurement intervals. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 137, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y. Temperature analysis of steel box girder considering actual wind field. Eng. Struct. 2021, 246, 113020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, N.; Yi, X.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, G.; Zheng, Y. Assessing simulated summer 10-m wind speed over China: Influencing processes and sensitivities to land surface schemes. Clim. Dynam. 2018, 50, 4189–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Ko, H.; Liu, F.; Chen, P.; Chang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Jang, H.; Lin, T.; Chen, Y. Fractal dimension of wind speed time series. Appl. Energy 2012, 93, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.B. Use of spatio-temporal calibrated wind shear model to improve accuracy of wind resource assessment. Appl. Energy 2018, 213, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrt, L.; Richardson, S.; Stauffer, D.; Seaman, N. Nocturnal wind-directional shear in complex terrain. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 140, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Huang, J.; Guo, R.; Yu, H.; Lin, P.; Zhang, Y. Role of radiatively forced temperature changes in enhanced semi-arid warming in the cold season over east Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 13777–13786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Ge, M.; Zeng, C.; Cui, G.; Liu, Y. Influence of atmospheric stability on wind-turbine wakes with a certain hub-height turbulence intensity. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 055111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Liu, J.; Wan, J.; Li, F.; Guo, Y.; Yu, D. The analysis of turbulence intensity based on wind speed data in onshore wind farms. Renew. Energy 2018, 123, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, B. Differences in wind farm energy production based on the atmospheric stability dissipation rate: Case study of a 30 MW onshore wind farm. Energy 2022, 239, 122380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, W.; Gu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shu, Z. Investigation of hilly terrain wind characteristics considering the interference effect. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerod. 2023, 241, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, H.; Gao, X. Investigation into wind turbine wake effect on complex terrain. Energy 2023, 269, 126767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Szoeke, S.P.; Bretherton, C.S. Variability in the Southerly Flow into the Eastern Pacific ITCZ. J. Atmos. Sci. 2005, 62, 4400–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ho, L. Rainy Season of the Asian–Pacific Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 2005, 15, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment; National Bureau of Statistics. Announcement on the Release of 2023 Power Carbon Dioxide Emission Factors; Ministry of Ecology and Environment and National Bureau of Statistics: Beijing, China, 2025. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk01/202512/t20251231_1139517.html (accessed on 15 January 2026).

| Height | GEV | Gamma | Gumbel | Weibull |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 m | 0.0131 | 0.0149 | 0.0313 | 0.0099 |

| 50 m | 0.0123 | 0.0124 | 0.0275 | 0.0067 |

| 80 m | 0.0153 | 0.0146 | 0.0282 | 0.0074 |

| 100 m | 0.0141 | 0.0136 | 0.0274 | 0.0092 |

| 120 m | 0.0145 | 0.0125 | 0.0277 | 0.0097 |

| 140 m | 0.0157 | 0.0120 | 0.0245 | 0.0108 |

| Height | GEV | Gamma | Gumbel | Weibull |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 m | 0.0428 | 0.0338 | 0.0440 | 0.0333 |

| 50 m | 0.0430 | 0.0344 | 0.0441 | 0.0337 |

| 80 m | 0.0421 | 0.0358 | 0.0451 | 0.0329 |

| 100 m | 0.0410 | 0.0372 | 0.0460 | 0.0320 |

| 120 m | 0.0401 | 0.0365 | 0.0450 | 0.0305 |

| 140 m | 0.0392 | 0.0374 | 0.0454 | 0.0299 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhang, S.; Cao, L.; Meng, X.; Jiang, L.; Ji, X.; Zhao, T. Assessment of Vertical Wind Characteristics for Wind Energy Utilization and Carbon Emission Reduction. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010102

Jiang L, Shi C, Zhang S, Cao L, Meng X, Jiang L, Ji X, Zhao T. Assessment of Vertical Wind Characteristics for Wind Energy Utilization and Carbon Emission Reduction. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Li, Changqing Shi, Shijia Zhang, Lvbing Cao, Xiangdong Meng, Ligang Jiang, Xiaodong Ji, and Tingning Zhao. 2026. "Assessment of Vertical Wind Characteristics for Wind Energy Utilization and Carbon Emission Reduction" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010102

APA StyleJiang, L., Shi, C., Zhang, S., Cao, L., Meng, X., Jiang, L., Ji, X., & Zhao, T. (2026). Assessment of Vertical Wind Characteristics for Wind Energy Utilization and Carbon Emission Reduction. Atmosphere, 17(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010102