Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.d.S. and R.A.P.d.F.; methodology, R.B.d.S., R.A.P.d.F. and B.T.S.; software, R.A.P.d.F. and B.T.S.; validation, R.B.d.S., R.A.P.d.F. and B.T.S.; formal analysis, B.T.S., R.A.P.d.F. and R.B.d.S.; investigation, B.T.S.; resources, R.B.d.S.; data curation, R.A.P.d.F. and B.T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T.S.; writing—review and editing, R.B.d.S., R.A.P.d.F., M.A.N. and C.K.P.; visualization, B.T.S. and R.B.d.S.; supervision, R.B.d.S., R.A.P.d.F. and M.A.N.; project administration, R.B.d.S.; funding acquisition, R.B.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Averaged SST field for the study period along the 38° W transect during the PBR18-3 campaign, denoted by the black line. The radiosonde (white circles) and XBT (black circles) markers are the launching positions during both the northbound (n) and southbound (s) paths. The dashed grey lines separate the inside and outside of the ITCZ, as defined in

Section 3.1.

Figure 1.

Averaged SST field for the study period along the 38° W transect during the PBR18-3 campaign, denoted by the black line. The radiosonde (white circles) and XBT (black circles) markers are the launching positions during both the northbound (n) and southbound (s) paths. The dashed grey lines separate the inside and outside of the ITCZ, as defined in

Section 3.1.

Figure 2.

Meridional sections of the atmospheric mixing ratio () and the meridional component of the wind in the atmosphere up to 2000 m during the northbound (a) and southbound (b) paths of the ship’s route in the PBR18-3 campaign. The difference in between the two paths of the ship’s route can be seen in (c).

Figure 2.

Meridional sections of the atmospheric mixing ratio () and the meridional component of the wind in the atmosphere up to 2000 m during the northbound (a) and southbound (b) paths of the ship’s route in the PBR18-3 campaign. The difference in between the two paths of the ship’s route can be seen in (c).

Figure 3.

Map of the mean OLR in the WTAO during both northbound (a) and southbound (b) paths of the ship’s route in the PBR18-3 campaign. The difference in OLR between the two paths of the ship’s route (black line) can be seen in (c). The radiosonde (black circles) launching positions taken during the PBR18-3 campaign are also shown.

Figure 3.

Map of the mean OLR in the WTAO during both northbound (a) and southbound (b) paths of the ship’s route in the PBR18-3 campaign. The difference in OLR between the two paths of the ship’s route (black line) can be seen in (c). The radiosonde (black circles) launching positions taken during the PBR18-3 campaign are also shown.

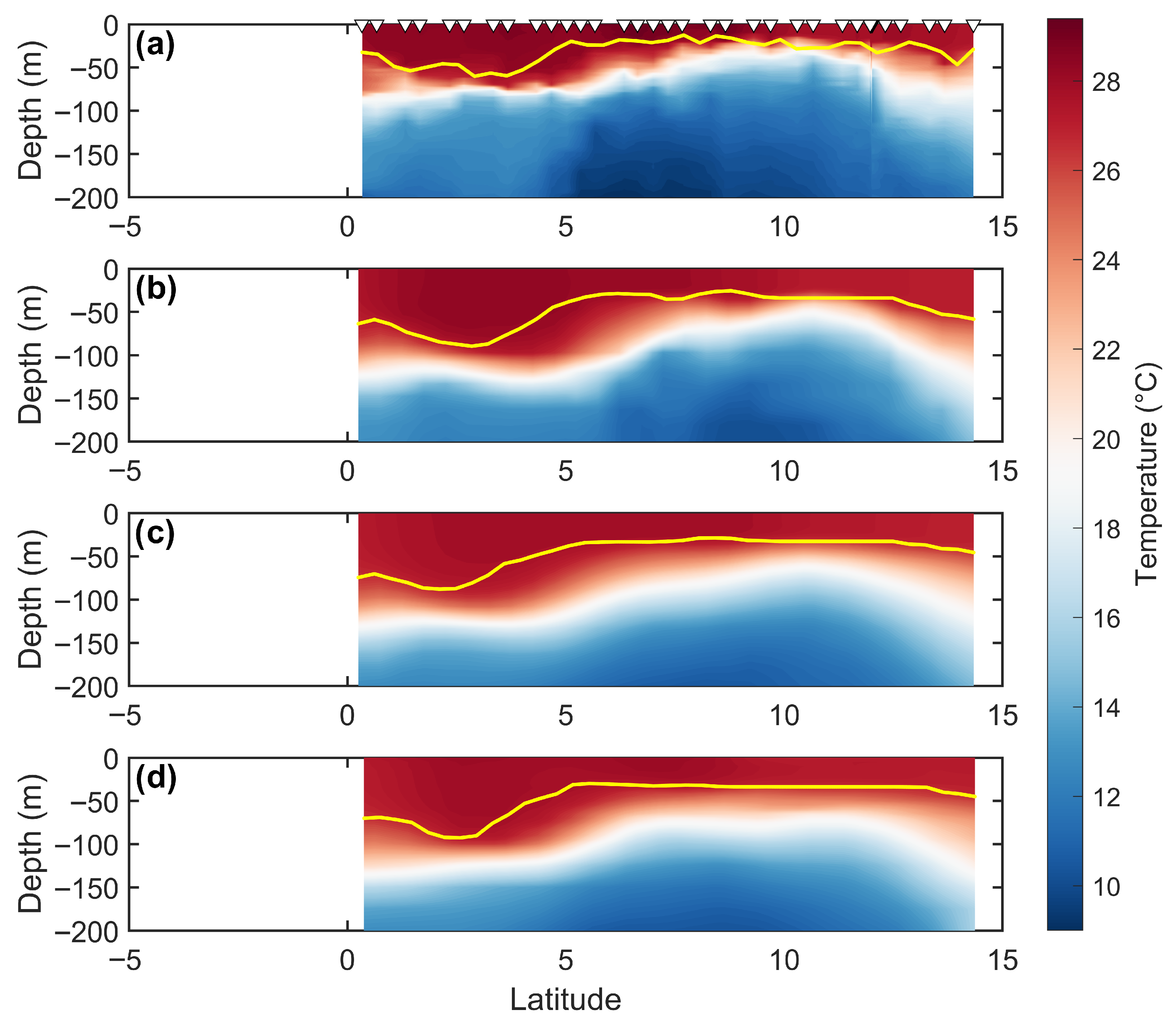

Figure 4.

Vertical water temperature transects at the 38° W meridian based on (a) XBT data obtained during the northbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign, (b) ORAS5 data for October 2018, (c) ORAS5 October climatology, and (d) WOA23 October climatology. The white triangles represent the launched XBTs, while the estimated ILD along the transects is shown as a yellow line for each dataset.

Figure 4.

Vertical water temperature transects at the 38° W meridian based on (a) XBT data obtained during the northbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign, (b) ORAS5 data for October 2018, (c) ORAS5 October climatology, and (d) WOA23 October climatology. The white triangles represent the launched XBTs, while the estimated ILD along the transects is shown as a yellow line for each dataset.

Figure 5.

Vertical water temperature transects at the 38° W meridian based on (a) XBT data obtained during the southbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign, (b) ORAS5 data for November 2018, (c) ORAS5 November climatology, and (d) WOA23 November climatology. The white triangles represent the launched XBTs, while the estimated ILD along the transects is shown as a yellow line for each dataset.

Figure 5.

Vertical water temperature transects at the 38° W meridian based on (a) XBT data obtained during the southbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign, (b) ORAS5 data for November 2018, (c) ORAS5 November climatology, and (d) WOA23 November climatology. The white triangles represent the launched XBTs, while the estimated ILD along the transects is shown as a yellow line for each dataset.

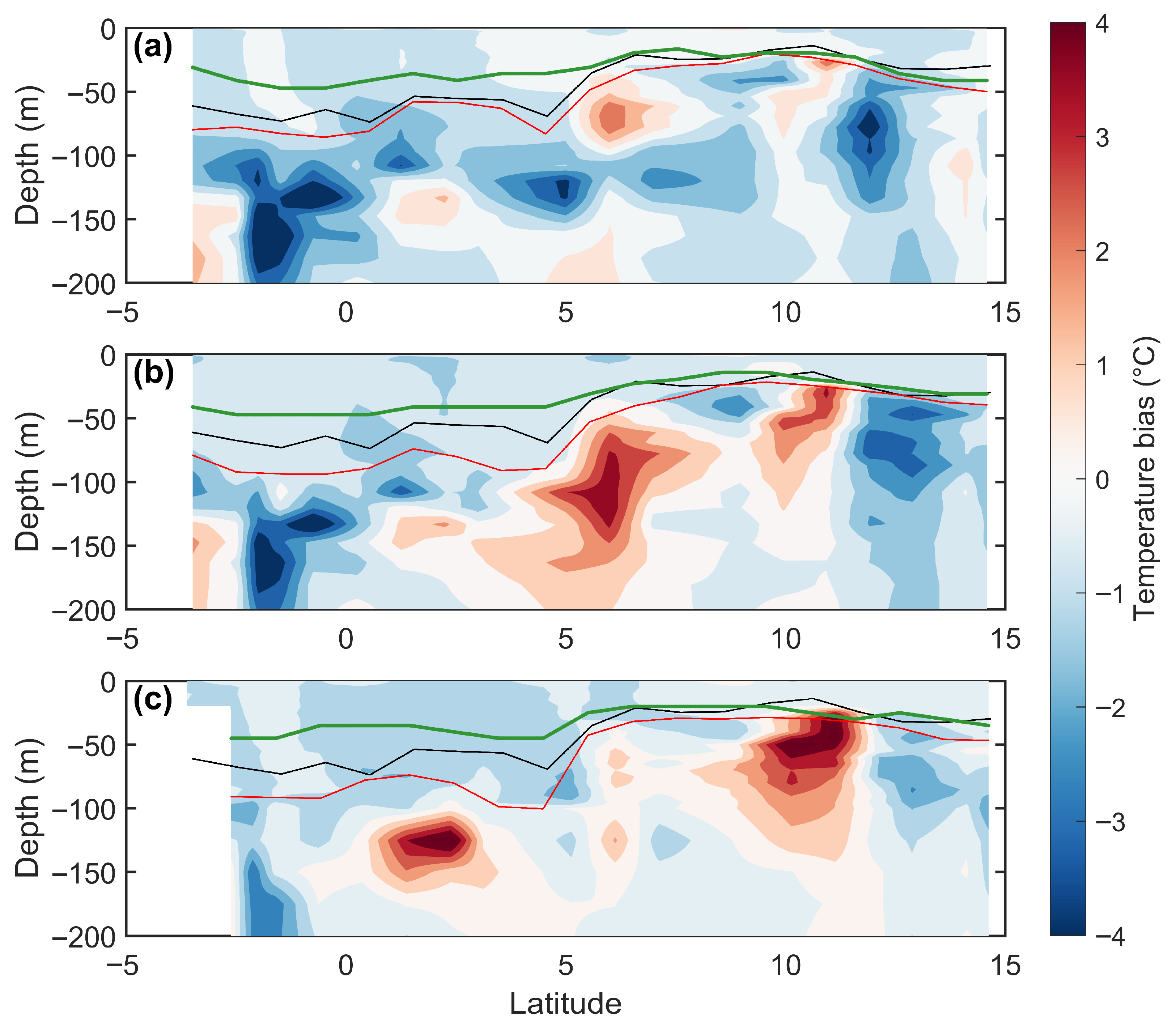

Figure 6.

Water temperature difference (biases) transects between observational (XBT) and other datasets obtained for the northbound path of the PRB18-3 campaign: (a) ORAS5 October 2018 average minus XBT; (b) ORAS5 October climatology minus XBT, and (c) WOA23 October climatology minus XBT. The ILD estimated from the XBT data is shown by the black line, while the ILD (MLD) estimated from each other dataset is shown by the red (green) line.

Figure 6.

Water temperature difference (biases) transects between observational (XBT) and other datasets obtained for the northbound path of the PRB18-3 campaign: (a) ORAS5 October 2018 average minus XBT; (b) ORAS5 October climatology minus XBT, and (c) WOA23 October climatology minus XBT. The ILD estimated from the XBT data is shown by the black line, while the ILD (MLD) estimated from each other dataset is shown by the red (green) line.

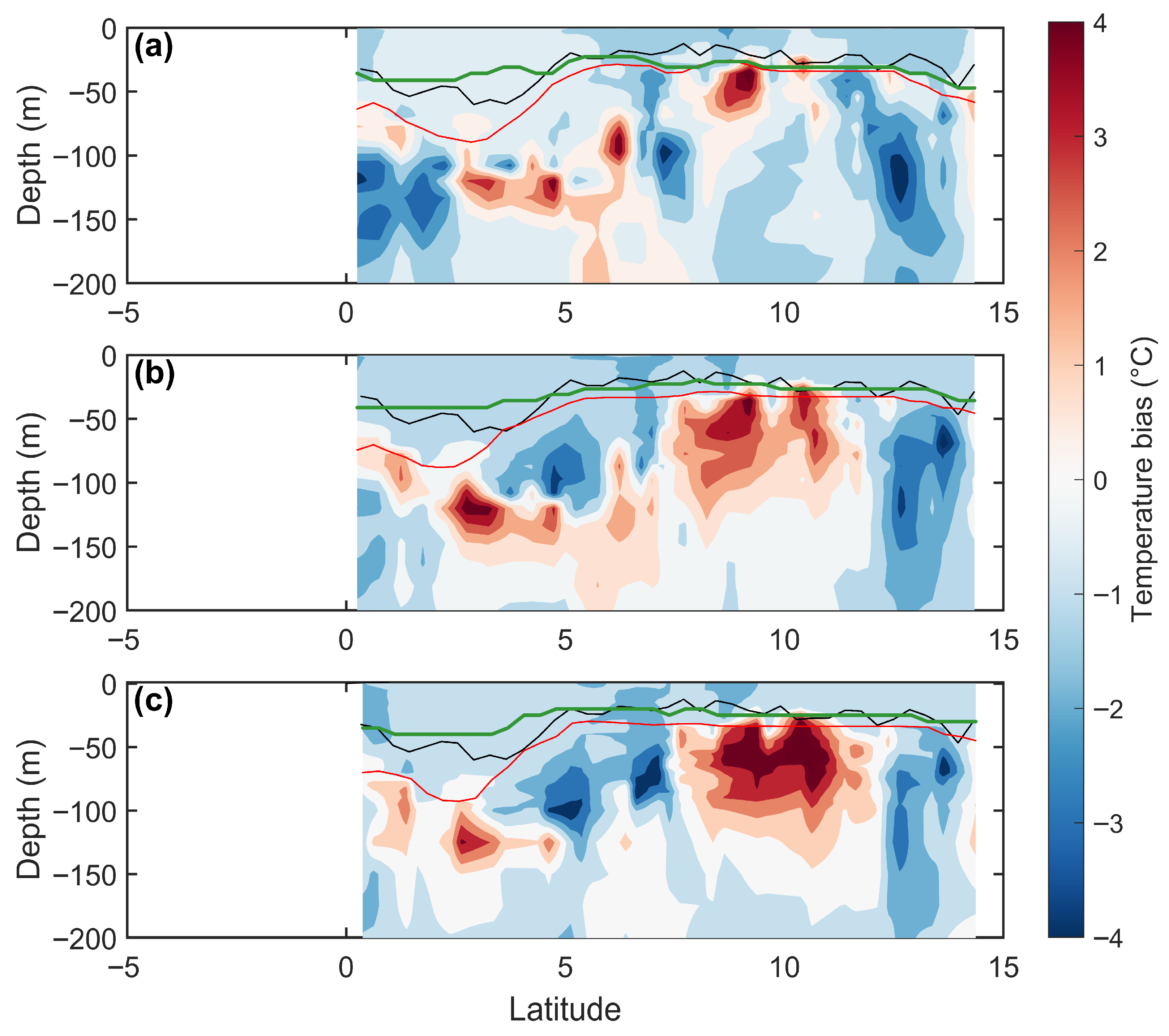

Figure 7.

Water temperature difference (biases) transects between observational (XBT) and other datasets obtained for the southbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign: (a) ORAS5 November 2018 average minus XBT; (b) ORAS5 November climatology minus XBT, and (c) WOA23 November climatology minus XBT. The ILD estimated from the XBT data is shown by the black line, while the ILD (MLD) estimated from each other dataset is shown by the red (green) line.

Figure 7.

Water temperature difference (biases) transects between observational (XBT) and other datasets obtained for the southbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign: (a) ORAS5 November 2018 average minus XBT; (b) ORAS5 November climatology minus XBT, and (c) WOA23 November climatology minus XBT. The ILD estimated from the XBT data is shown by the black line, while the ILD (MLD) estimated from each other dataset is shown by the red (green) line.

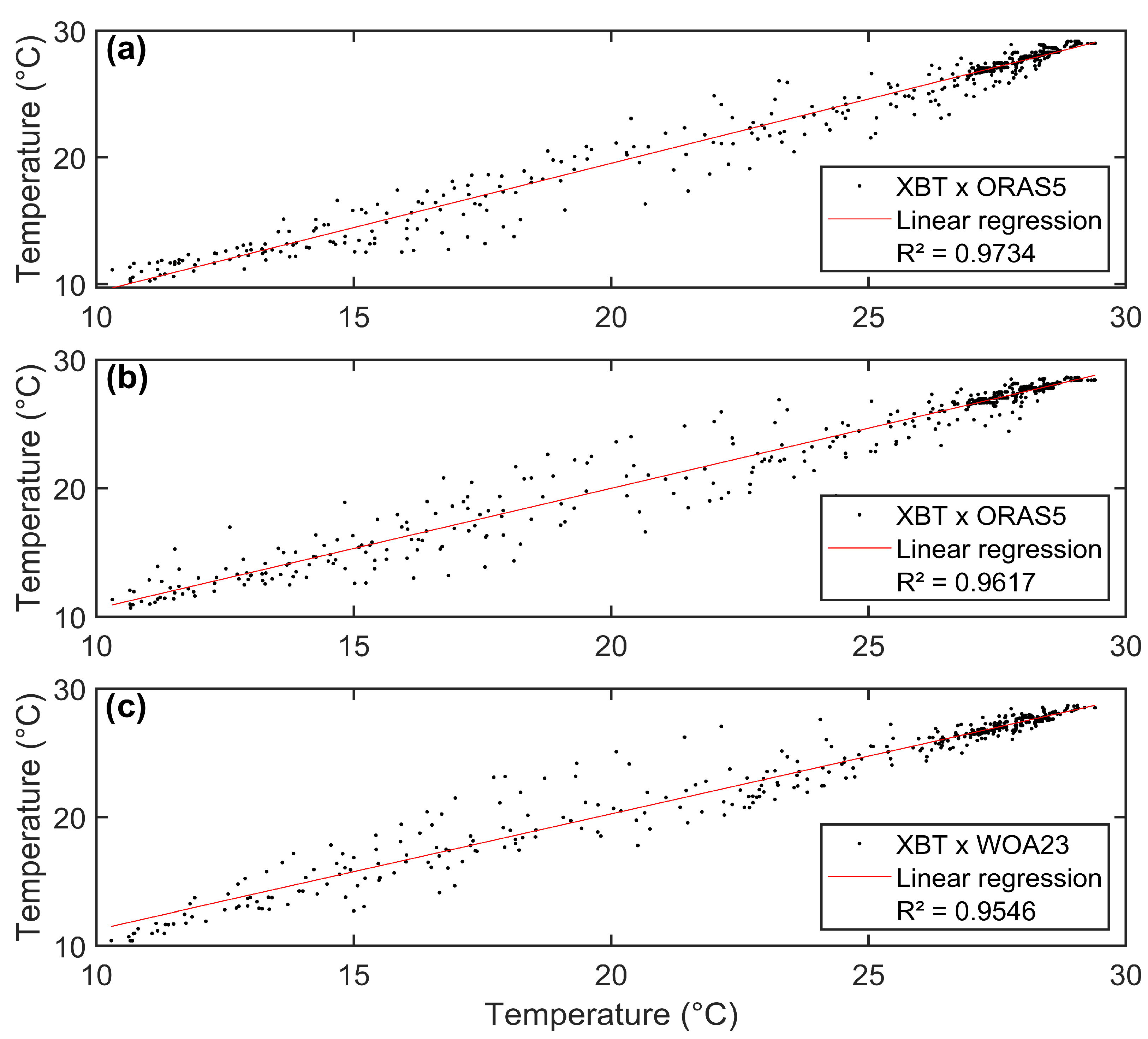

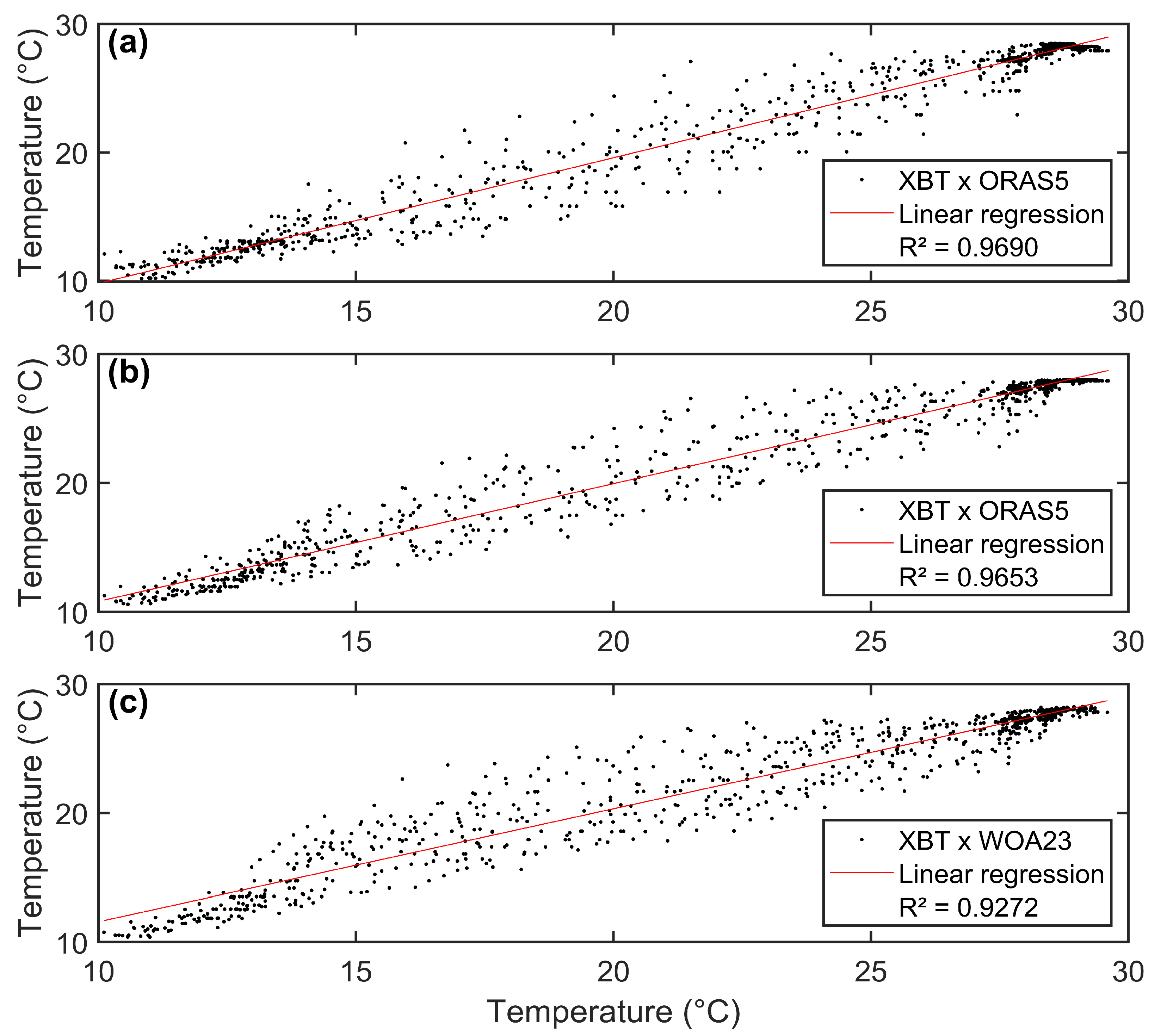

Figure 8.

Linear correlations between XBT and (a) ORAS5 October 2018; (b) ORAS5 October climatology; and (c) WOA23 October climatology for the northbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign.

Figure 8.

Linear correlations between XBT and (a) ORAS5 October 2018; (b) ORAS5 October climatology; and (c) WOA23 October climatology for the northbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign.

Figure 9.

Linear correlations between XBT and (a) ORAS5 November 2018; (b) ORAS5 November climatology; and (c) WOA23 November climatology for the southbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign.

Figure 9.

Linear correlations between XBT and (a) ORAS5 November 2018; (b) ORAS5 November climatology; and (c) WOA23 November climatology for the southbound path of the PBR18-3 campaign.

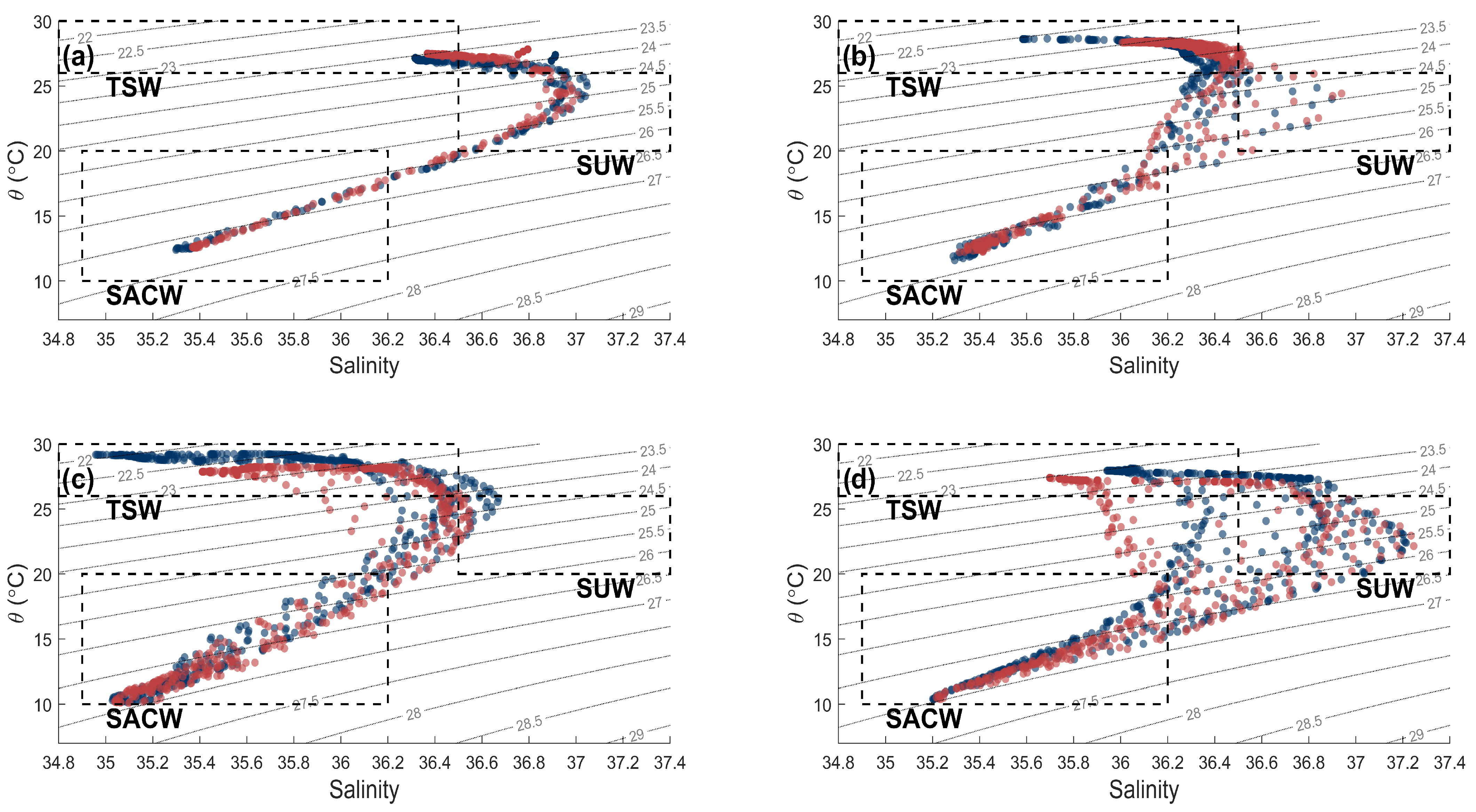

Figure 10.

θ-S diagrams of four latitudinal bands: 5° S–0° (a), 0°–5° N (b), 5° N–10° N (c), and 10° N–15° N (d), based on the ORAS5 October (dark blue) and November (dark red) climatologies. The dashed squares represent the θ and S ranges of each water mass: TSW, SUW and SACW.

Figure 10.

θ-S diagrams of four latitudinal bands: 5° S–0° (a), 0°–5° N (b), 5° N–10° N (c), and 10° N–15° N (d), based on the ORAS5 October (dark blue) and November (dark red) climatologies. The dashed squares represent the θ and S ranges of each water mass: TSW, SUW and SACW.

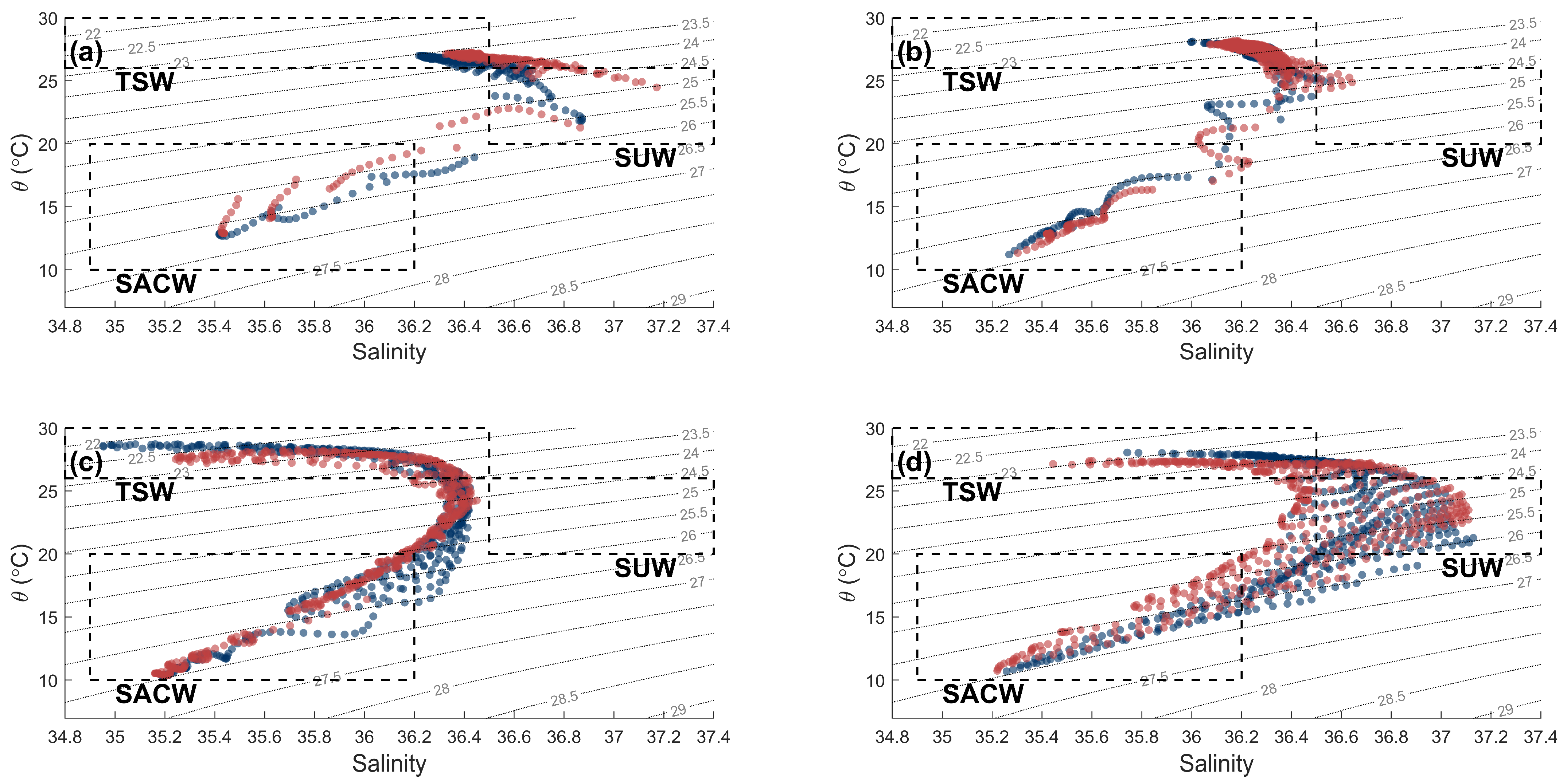

Figure 11.

θ-S diagrams of four latitudinal bands: 5° S–0° (a), 0°–5° N (b), 5° N–10° N (c), and 10° N–15° N (d), based on the WOA23 October (dark blue) and November (dark red) climatologies. The dashed squares represent the θ and S ranges of each water mass: TSW, SUW and SACW.

Figure 11.

θ-S diagrams of four latitudinal bands: 5° S–0° (a), 0°–5° N (b), 5° N–10° N (c), and 10° N–15° N (d), based on the WOA23 October (dark blue) and November (dark red) climatologies. The dashed squares represent the θ and S ranges of each water mass: TSW, SUW and SACW.

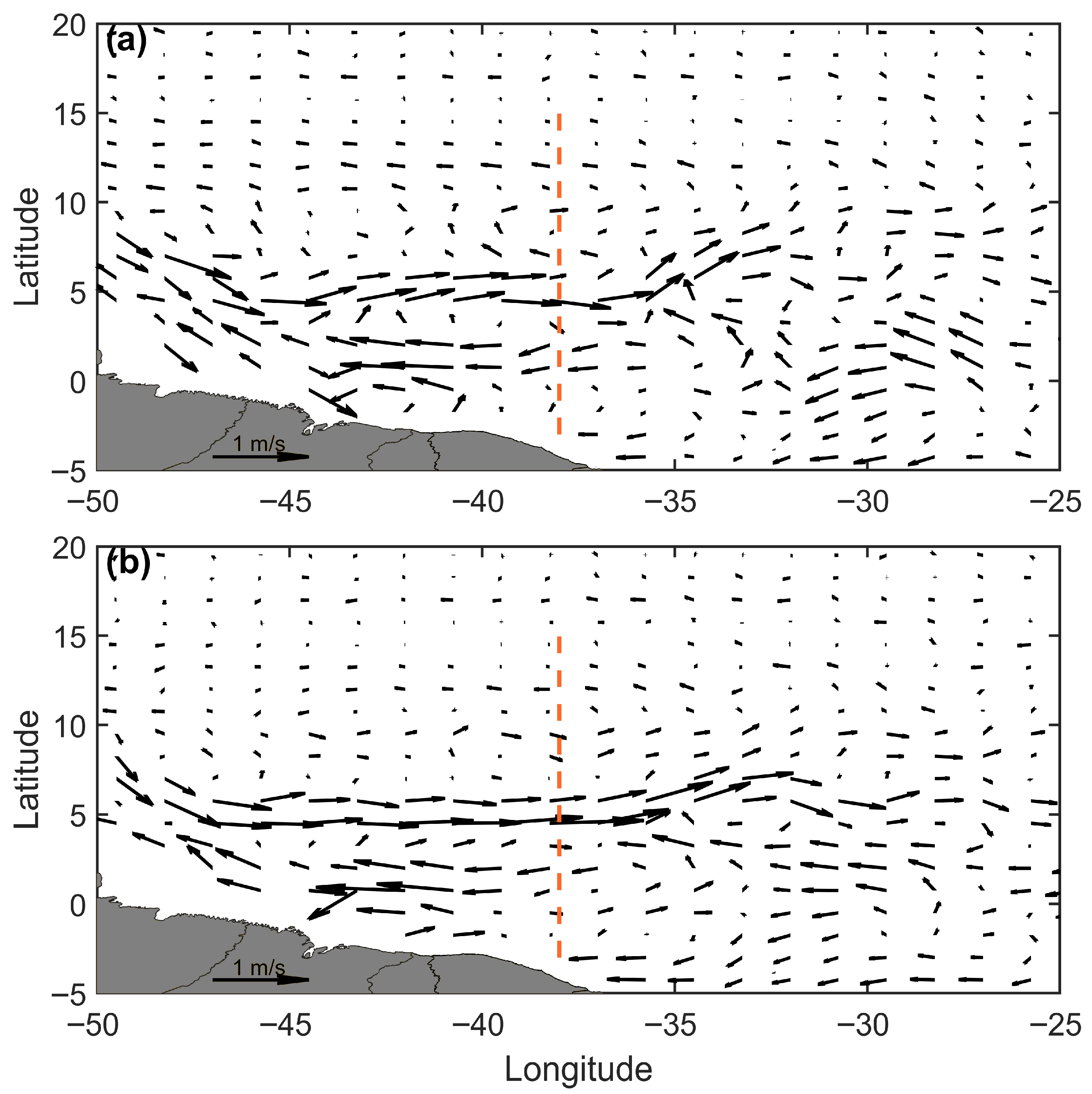

Figure 12.

Average ocean surface currents vectors (black arrows) for the northbound (a) and southbound (b) phases of the PBR18-3 campaign, based on data from Project OSCAR. The path sailed by the R/V Vital de Oliveira is represented by the dashed golden line.

Figure 12.

Average ocean surface currents vectors (black arrows) for the northbound (a) and southbound (b) phases of the PBR18-3 campaign, based on data from Project OSCAR. The path sailed by the R/V Vital de Oliveira is represented by the dashed golden line.

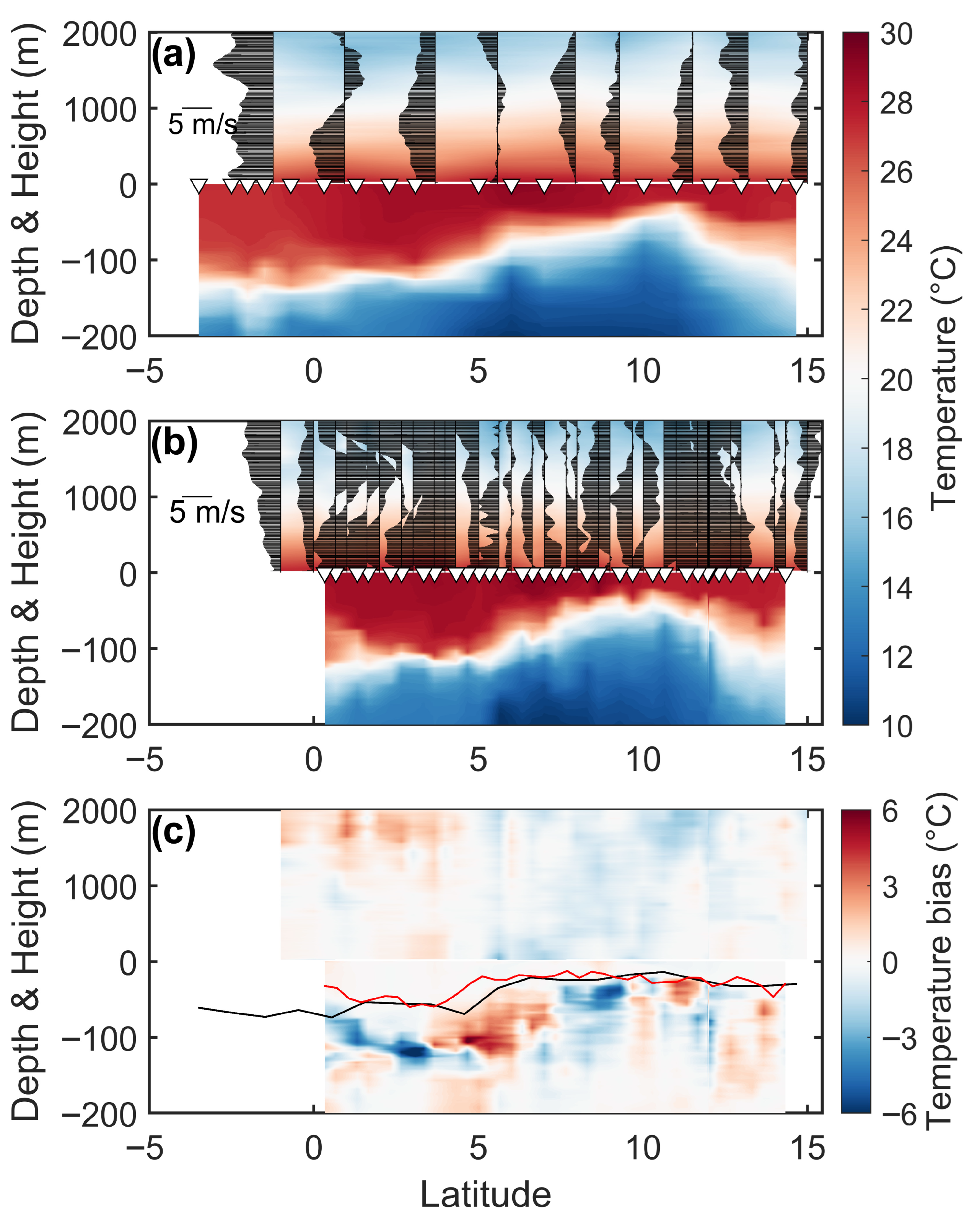

Figure 13.

Vertical water and air temperature transects at the 38° W meridian based on XBT and radiosonde data obtained during the northbound (a) and southbound (b) phases of the PBR18-3 campaign. The synoptic-scale difference between the southbound and northbound phases is also shown in (c), along with the white triangles representing the launched XBTs and the estimated ILD for each phase being represented by the black (northbound) and red lines (southbound).

Figure 13.

Vertical water and air temperature transects at the 38° W meridian based on XBT and radiosonde data obtained during the northbound (a) and southbound (b) phases of the PBR18-3 campaign. The synoptic-scale difference between the southbound and northbound phases is also shown in (c), along with the white triangles representing the launched XBTs and the estimated ILD for each phase being represented by the black (northbound) and red lines (southbound).

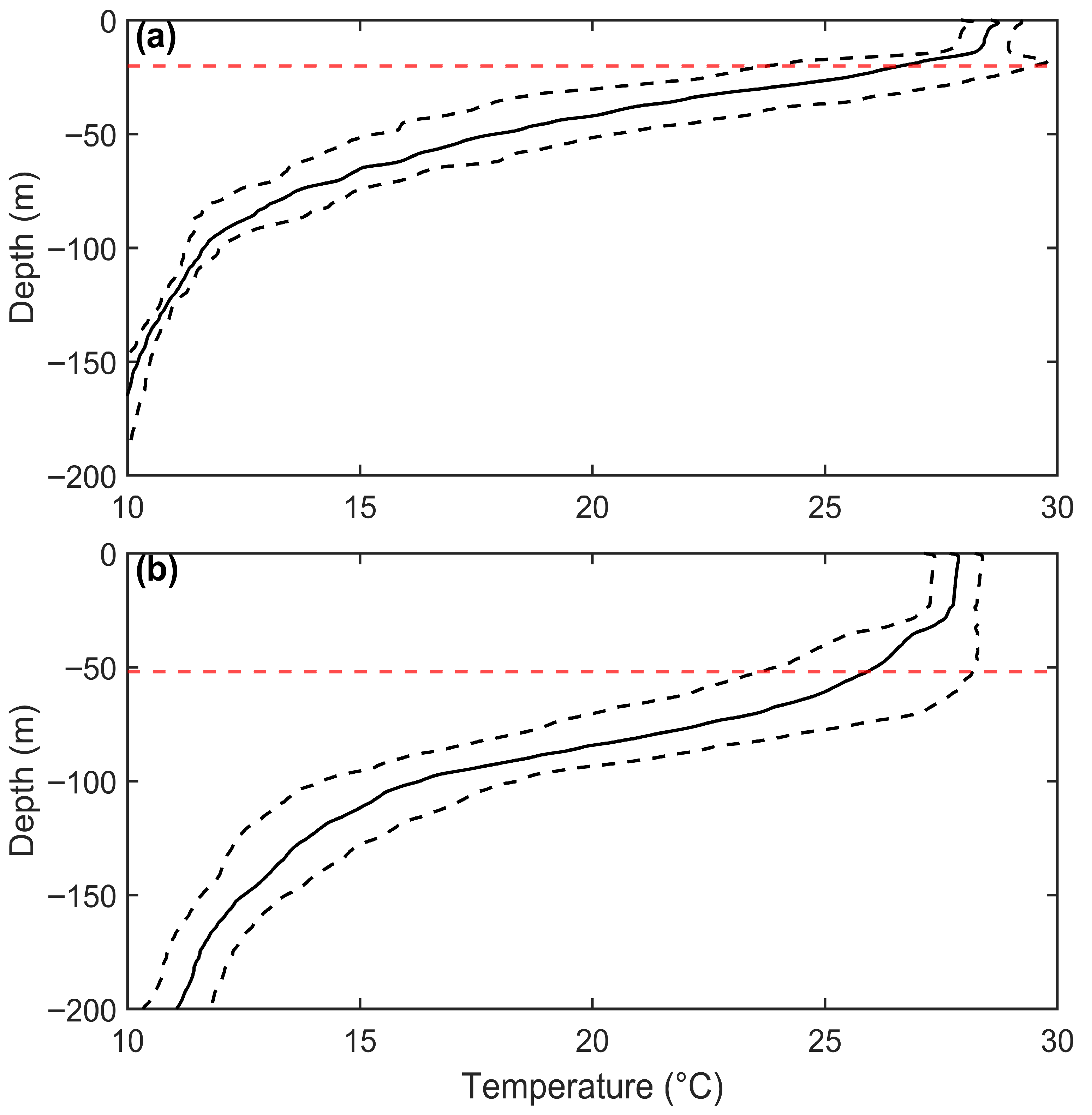

Figure 14.

Averaged XBT temperature (solid black lines) profiles (±standard deviation – dashed black lines) for inITCZ (a) and outITCZ (b) for the northbound phase. The red dashed line illustrates the average estimated ILD.

Figure 14.

Averaged XBT temperature (solid black lines) profiles (±standard deviation – dashed black lines) for inITCZ (a) and outITCZ (b) for the northbound phase. The red dashed line illustrates the average estimated ILD.

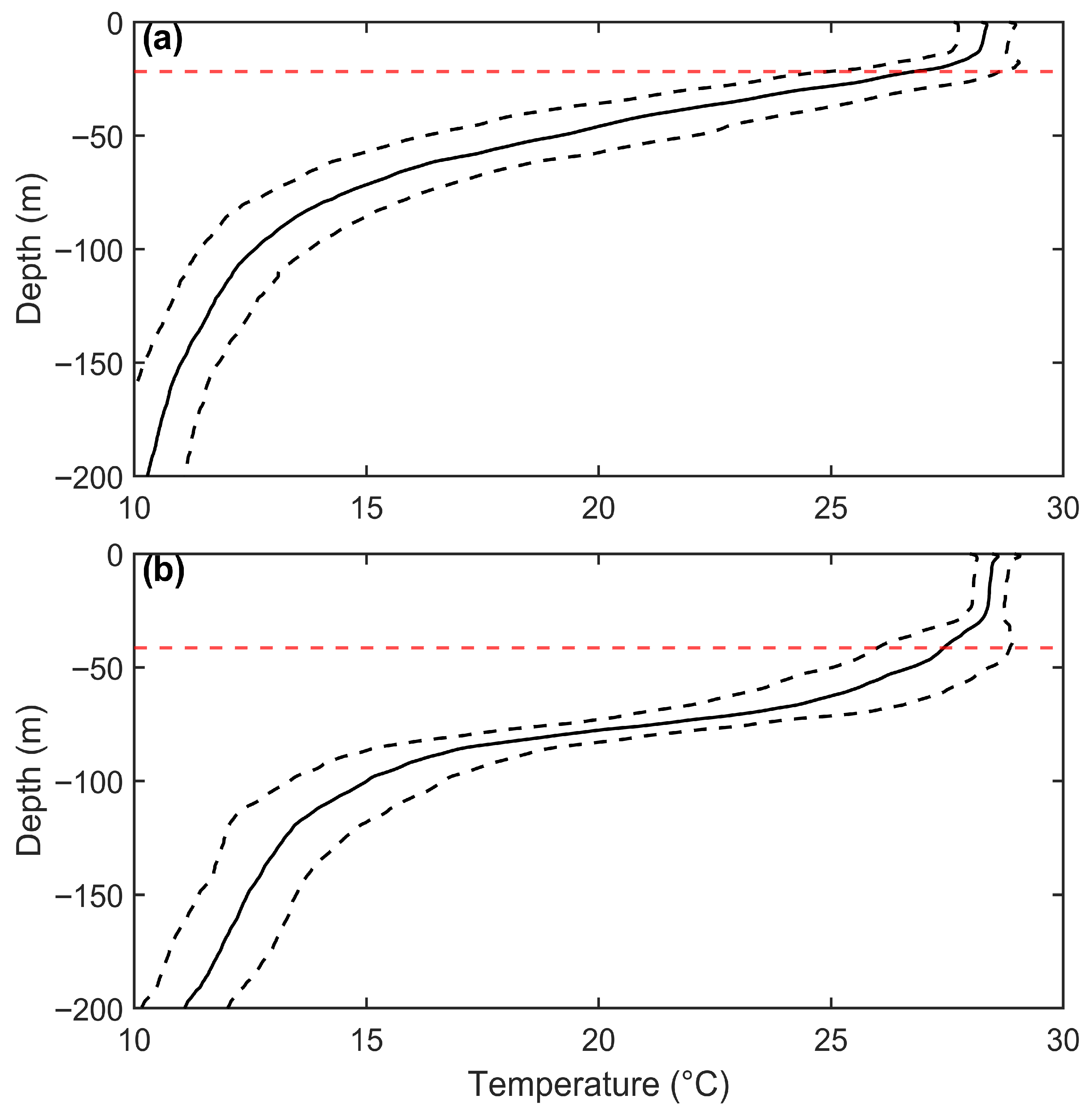

Figure 15.

Averaged XBT temperature (solid black lines) profiles (±standard deviation – dashed black lines) for inITCZ (a) and outITCZ (b) for the southbound phase. The red dashed line illustrates the average estimated ILD.

Figure 15.

Averaged XBT temperature (solid black lines) profiles (±standard deviation – dashed black lines) for inITCZ (a) and outITCZ (b) for the southbound phase. The red dashed line illustrates the average estimated ILD.

Table 1.

Radiosonde launching positions and dates for both northbound (R-1 to R-9) and southbound (R-10 to R-47) paths during the PBR18-3 campaign.

Table 1.

Radiosonde launching positions and dates for both northbound (R-1 to R-9) and southbound (R-10 to R-47) paths during the PBR18-3 campaign.

| Radiosonde | Date | Latitude | Longitude | Radiosonde | Date | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|

| R-1 | 18 October 2018 | −1.24 | −38.00 | R-25 | 1 November 2018 | 10.64 | −38.01 |

| R-2 | 19 October 2018 | 0.93 | −38.00 | R-26 | 1 November 2018 | 10.01 | −38.02 |

| R-3 | 20 October 2018 | 3.69 | −38.00 | R-27 | 1 November 2018 | 9.68 | −38.01 |

| R-4 | 21 October 2018 | 5.58 | −38.00 | R-28 | 2 November 2018 | 9.00 | −38.01 |

| R-5 | 22 October 2018 | 7.95 | −38.00 | R-29 | 2 November 2018 | 8.65 | −39.00 |

| R-6 | 23 October 2018 | 9.29 | −38.00 | R-30 | 2 November 2018 | 8.00 | −38.02 |

| R-7 | 24 October 2018 | 11.51 | −38.00 | R-31 | 3 November 2018 | 7.67 | −38.00 |

| R-8 | 25 October 2018 | 13.20 | −38.00 | R-32 | 3 November 2018 | 7.01 | −38.00 |

| R-9 | 26 October 2018 | 15.00 | −38.00 | R-33 | 4 November 2018 | 6.64 | −37.99 |

| R-10 | 26 October 2018 | 14.99 | −38.01 | R-34 | 4 November 2018 | 6.00 | −38.03 |

| R-11 | 27 October 2018 | 14.99 | −37.99 | R-35 | 4 November 2018 | 5.63 | −38.01 |

| R-12 | 27 October 2018 | 14.33 | −38.00 | R-36 | 5 November 2018 | 5.02 | −38.00 |

| R-13 | 27 October 2018 | 14.00 | −37.00 | R-37 | 5 November 2018 | 4.31 | −37.96 |

| R-14 | 28 October 2018 | 12.00 | −38.01 | R-38 | 5 November 2018 | 3.99 | −37.95 |

| R-15 | 28 October 2018 | 12.98 | −38.06 | R-39 | 5 November 2018 | 3.66 | −37.98 |

| R-16 | 29 October 2018 | 12.67 | −37.95 | R-40 | 6 November 2018 | 3.02 | −38.01 |

| R-17 | 30 October 2018 | 12.02 | −37.71 | R-41 | 6 November 2018 | 2.67 | −38.02 |

| R-18 | 30 October 2018 | 12.00 | −37.77 | R-42 | 6 November 2018 | 2.00 | −38.00 |

| R-19 | 30 October 2018 | 11.98 | −37.37 | R-43 | 7 November 2018 | 1.62 | −38.02 |

| R-20 | 30 October 2018 | 11.98 | −37.91 | R-44 | 7 November 2018 | 1.01 | −37.99 |

| R-21 | 31 October 2018 | 11.97 | −37.75 | R-45 | 7 November 2018 | 0.66 | −38.00 |

| R-22 | 31 October 2018 | 11.98 | −37.82 | R-46 | 8 November 2018 | −0.01 | −38.01 |

| R-23 | 31 October 2018 | 11.97 | −37.97 | R-47 | 8 November 2018 | −1.00 | −38.00 |

| R-24 | 31 October 2018 | 11.69 | −38.01 | | | | |

Table 2.

XBT launching positions and dates for both northbound (XBT-1 to XBT-19) and southbound (XBT-20 to XBT-58) paths during the PBR18-3 campaign.

Table 2.

XBT launching positions and dates for both northbound (XBT-1 to XBT-19) and southbound (XBT-20 to XBT-58) paths during the PBR18-3 campaign.

| XBT | Date | Latitude | Longitude | XBT | Date | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|

| XBT-1 | 17 October 2018 | −3.49 | −36.40 | XBT-30 | 31 October 2018 | 11.98 | −37.73 |

| XBT-2 | 18 October 2018 | −2.50 | −37.10 | XBT-31 | 31 October 2018 | 11.98 | −37.81 |

| XBT-3 | 18 October 2018 | −2.01 | −37.42 | XBT-32 | 31 October 2018 | 11.97 | −37.99 |

| XBT-4 | 18 October 2018 | −1.49 | −37.47 | XBT-33 | 31 October 2018 | 11.67 | −38.01 |

| XBT-5 | 18 October 2018 | −0.70 | −37.78 | XBT-34 | 1 November 2018 | 11.33 | −38.01 |

| XBT-6 | 19 October 2018 | 0.31 | −37.87 | XBT-35 | 1 November 2018 | 10.67 | −38.01 |

| XBT-7 | 19 October 2018 | 1.29 | −37.99 | XBT-36 | 1 November 2018 | 10.30 | −38.00 |

| XBT-8 | 19 October 2018 | 2.30 | −37.98 | XBT-37 | 2 November 2018 | 9.69 | −38.01 |

| XBT-9 | 20 October 2018 | 3.09 | −37.98 | XBT-38 | 2 November 2018 | 9.30 | −38.00 |

| XBT-10 | 21 October 2018 | 5.01 | −37.94 | XBT-39 | 2 November 2018 | 8.66 | −37.99 |

| XBT-11 | 21 October 2018 | 6.01 | −37.97 | XBT-40 | 2 November 2018 | 8.31 | −37.98 |

| XBT-12 | 21 October 2018 | 7.00 | −38.02 | XBT-41 | 3 November 2018 | 7.67 | −38.00 |

| XBT-13 | 23 October 2018 | 8.98 | −38.01 | XBT-42 | 3 November 2018 | 7.34 | −38.00 |

| XBT-14 | 23 October 2018 | 10.03 | −38.01 | XBT-43 | 3 November 2018 | 7.01 | −38.00 |

| XBT-15 | 24 October 2018 | 11.02 | −38.00 | XBT-44 | 4 November 2018 | 6.64 | −37.99 |

| XBT-16 | 24 October 2018 | 12.04 | −37.96 | XBT-45 | 4 November 2018 | 6.34 | −37.99 |

| XBT-17 | 25 October 2018 | 12.99 | −38.01 | XBT-46 | 4 November 2018 | 5.67 | −38.01 |

| XBT-18 | 25 October 2018 | 14.01 | −38.02 | XBT-47 | 4 November 2018 | 5.34 | −37.99 |

| XBT-19 | 25 October 2018 | 14.67 | −38.01 | XBT-48 | 5 November 2018 | 5.03 | −38.00 |

| XBT-20 | 27 October 2018 | 14.33 | −38.00 | XBT-49 | 5 November 2018 | 4.67 | −37.98 |

| XBT-21 | 27 October 2018 | 13.67 | −38.00 | XBT-50 | 5 November 2018 | 4.33 | −37.96 |

| XBT-22 | 28 October 2018 | 13.33 | −38.01 | XBT-51 | 5 November 2018 | 3.67 | −37.98 |

| XBT-23 | 28 October 2018 | 12.67 | −38.06 | XBT-52 | 6 November 2018 | 3.34 | −38.00 |

| XBT-24 | 29 October 2018 | 12.32 | −38.06 | XBT-53 | 6 November 2018 | 2.67 | −38.02 |

| XBT-25 | 29 October 2018 | 12.00 | −37.93 | XBT-54 | 6 November 2018 | 2.34 | −38.01 |

| XBT-26 | 30 October 2018 | 11.99 | −37.61 | XBT-55 | 7 November 2018 | 1.66 | −38.02 |

| XBT-27 | 30 October 2018 | 12.02 | −37.70 | XBT-56 | 7 November 2018 | 1.32 | −38.02 |

| XBT-28 | 30 October 2018 | 11.97 | −37.91 | XBT-57 | 7 November 2018 | 0.67 | −38.00 |

| XBT-29 | 30 October 2018 | 11.99 | −37.76 | XBT-58 | 7 November 2018 | 0.33 | −38.01 |

Table 3.

Specifications of the open-access datasets used in this paper.

Table 3.

Specifications of the open-access datasets used in this paper.

| Dataset | Horizontal Resolution | Vertical Resolution | Period | Climatology |

|---|

| ORAS5 | 0.25° × 0.25° | 75 | October and November 2018 | - |

| ORAS5 | 0.25° × 0.25° | 75 | October and November | 1981–2010 |

| WOA23 | 0.25° × 0.25° | 57 | October and November | 1981–2010 |

Table 4.

Average values (plus standard deviations) for , , and OLR in the ITCZ and out of ITCZ regions during both northbound and southbound phases.

Table 4.

Average values (plus standard deviations) for , , and OLR in the ITCZ and out of ITCZ regions during both northbound and southbound phases.

| Zone | (g/kg) | (°C) | OLR (W/m2) |

|---|

| Northbound | Southbound | Northbound | Southbound | Northbound | Southbound |

|---|

| inITCZ | 12.40 ± 1.15 | 12.39 ± 1.55 | 18.52 ± 1.33 | 17.87 ± 1.49 | 237.37 ± 4.97 | 214.96 ± 9.61 |

| outITCZ | 11.84 ± 1.88 | 10.32 ± 2.75 | 17.90 ± 1.37 | 18.28 ± 1.20 | 268.44 ± 26.10 | 274.35 ± 19.79 |

Table 5.

Average ILD and standard deviations (in meters) estimated from XBT, ORAS5, and WOA23 data during the northbound (October) and southbound (November) paths in the ITCZ and outside ITCZ regions.

Table 5.

Average ILD and standard deviations (in meters) estimated from XBT, ORAS5, and WOA23 data during the northbound (October) and southbound (November) paths in the ITCZ and outside ITCZ regions.

| Dataset | Zone | Northbound (October) | Southbound (November) |

|---|

| XBT | inITCZ | −20.2 ± 4.6 | −21.83 ± 5.23 |

| outITCZ | −51.97 ± 17.69 | −41.4 ± 12.91 |

| ORAS5 monthly | inITCZ | −26.81 ± 5.24 | −32.0 ± 3.25 |

| outITCZ | −63.03 ± 18.72 | −64.43 ± 16.87 |

| ORAS5 climatology | inITCZ | −28.79 ± 7.91 | −32.44 ± 1.97 |

| outITCZ | −69.47 ± 25.64 | −60.77 ± 19.67 |

| WOA23 climatology | inITCZ | −29.88 ± 1.23 | −32.65 ± 1.33 |

| outITCZ | −70.0 ± 25.35 | −61.02 ± 21.19 |

Table 6.

Average biases (±standard deviation), with t-test statistics for p < 0.05, p-value, upper and lower confidence intervals, and RMSE between ORAS5, WOA23, and the XBT data for the northbound phase of the PBR18-3 campaign.

Table 6.

Average biases (±standard deviation), with t-test statistics for p < 0.05, p-value, upper and lower confidence intervals, and RMSE between ORAS5, WOA23, and the XBT data for the northbound phase of the PBR18-3 campaign.

| Database | Zone | Bias (°C) | RMSE | T-Stat | p-Value | CI-Lower | CI-Upper |

|---|

| ORAS5 monthly | inITCZ | −0.17 ± 0.78 | 0.80 | −6.05 | 2.22 × 10−9 | −0.23 | −0.11 |

| outITCZ | −0.47 ± 0.76 | 0.89 | −23.67 | 4.75 × 10−105 | −0.51 | −0.43 |

| ORAS5 climatology | inITCZ | 0.25 ± 1.03 | 1.06 | 6.78 | 2.30 × 10−11 | 0.18 | 0.32 |

| outITCZ | −0.47 ± 0.81 | 0.94 | −22.24 | 1.43 × 10−94 | −0.51 | −0.43 |

| WOA23 climatology | inITCZ | 0.70 ± 1.28 | 1.46 | 13.69 | 1.78 × 10−37 | 0.60 | 0.80 |

| outITCZ | −0.50 ± 0.67 | 0.84 | −24.79 | 2.29 × 10−108 | −0.54 | −0.46 |

Table 7.

Average biases (±standard deviation), with t-test statistics for p < 0.05, p-value, upper and lower confidence intervals, and RMSE between ORAS5, WOA23, and the XBT data for the southbound phase of the PBR18-3 campaign.

Table 7.

Average biases (±standard deviation), with t-test statistics for p < 0.05, p-value, upper and lower confidence intervals, and RMSE between ORAS5, WOA23, and the XBT data for the southbound phase of the PBR18-3 campaign.

| Database | Zone | Bias (°C) | RMSE | T-Stat | p-Value | CI-Lower | CI-Upper |

|---|

| ORAS5 monthly | inITCZ | −0.03 ± 1.27 | 1.27 | −0.78 | 0.43 | −0.12 | 0.05 |

| outITCZ | −0.63 ± 0.90 | 1.09 | −20.31 | 7.15 × 10−75 | −0.69 | −0.57 |

| ORAS5 climatology | inITCZ | −0.43 ± 1.00 | 1.09 | −12.99 | 1.69 × 10−35 | −0.50 | −0.37 |

| outITCZ | −0.32 ± 0.76 | 0.82 | −12.15 | 2.22 × 10−31 | −0.37 | −0.27 |

| WOA23 climatology | inITCZ | 0.50 ± 1.93 | 2.00 | 7.03 | 4.94 × 10−12 | 0.36 | 0.65 |

| outITCZ | −0.58 ± 0.86 | 1.04 | −17.62 | 1.99 × 10−57 | −0.65 | −0.52 |

Table 8.

Average and SST values (with standard deviations) for the ITCZ and out of ITCZ regions during the northbound and southbound phases.

Table 8.

Average and SST values (with standard deviations) for the ITCZ and out of ITCZ regions during the northbound and southbound phases.

| Zone | (°C) | SST (°C) |

|---|

| Northbound | Southbound |

|---|

| inITCZ | 17.55 ± 6.40 | 17.88 ± 6.33 |

| outITCZ | 21.95 ± 5.95 | 21.83 ± 6.30 |