1. Introduction

The year 2024 marked a century since Anders Knutsson Ångström published his famous work [

1] correlating solar irradiation with sunshine duration. Technically, the Ångström equation linearly correlates the clear sky index

kcs with the relative sunshine

σ:

The clear sky index

is defined as the ratio of the solar irradiation

H recorded over the time interval

S to the estimated clear-sky solar irradiation

H0 over the same time interval. Relative sunshine

is defined as the ratio of the sunshine duration

S0 over the time interval

S.

obviously signifies the mean cloud transmittance in

S. From the computational perspective,

is an empirical parameter which is estimated based on measurements of

H and

S0. The original Ångström equation was developed based on monthly global solar irradiation and sunshine duration recorded in Stockholm, Sweden, finding

[

1].

Twenty years later, James Arthur Prescott removed the uncertainty associated with the estimation of the clear-sky solar irradiation from Equation (1) [

2]. Prescott replaced

H0 with extraterrestrial solar irradiation

He, a physical quantity deterministically calculated at the upper boundary of the atmosphere. In its general form, the resulting equation linearly correlates clearness index with the relative sunshine:

The fraction

defines the clearness index [

3] which accounts for all random meteorological influences, being a measure of the mean atmospheric transparency over the period

S. In recognition of the two pioneers’ contribution to the development of solar irradiance modeling, Equation (2) is called the Ångström–Prescott (A–P) equation.

Examining Equation (2) at the boundaries of the

domain (overcast and clear skies in

S), the empirical parameters

a and

b acquire the following meanings (e.g., [

4]):

and

. From these two relations, two useful equations for the climatological study of cloudless atmospheric transparency

and cloud transmittance

can be immediately deduced:

Over time, the Ångström and A–P equations have been the subject of many studies, and developments in the sense of replacing the linear equation with different non-linear equations, including other predictors, such as local latitude and altitude, season, and others. For a deeper explanation of the Ångström equation, the reader is directed to [

4]. The study substantiates the Ångström equation from a theoretical perspective and provide an intercomparison of different empirical Ångström equations [

4]. For more details on the A–P equation, the reader is directed to [

5,

6,

7]. Reference [

5] presents a comparative study on the influence of different parameters (latitude, altitude, season, local climatology) on the performance of 33 different A–P equations. The study concludes that an empirical A–P equation comprising relative sunshine, altitude, and the month index as input parameters can explain coarsely 90% of the variability in the clearness index data [

5]. By testing a wide variety of the A-P equations against data collected from 924 sites spread around the world, the review [

6] shows that some equations can achieve high-performance in many places around the globe. When estimating monthly global solar irradiation, it is already documented that the performance of simple A–P equations is comparable to that of online platforms NASA POWER, MERRA2, ERA5, and CAMS [

7]. A recent study [

8] used 33 linear and non-linear forms of the A–P equation for daily, monthly and annual estimation of solar irradiation in Athens, Greece. The in-depth analysis showed that at the three-time scales, the best performance is not secured by the same type of A–P equation. The A–P equation proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization for global applicability showed comparable accuracy with the best-performing model at the daily scale only [

8]. In an effort to broaden the applicability of the A–P equation, several studies have examined the possibility of replacing relative sunshine with air temperature, which is the atmospheric variable measured with the highest spatial coverage (e.g., [

9]). From all these references it can be concluded that over time most studies have focused on identifying a high-performance A–P equation over an extended geographical area and on increasing the accuracy of the A–P equation in estimating solar irradiation.

This study re-examines the A–P equation from a distinct perspective, namely its potential for deriving information on atmospheric climatology through radiometric measurements. Although the core idea is not entirely new, the literature that addresses this specific application is very limited. This scarcity is particularly evident when compared with the extensive body of research that uses the equation for estimating solar irradiation. Furthermore, most of the few available studies discuss this aspect only marginally. Some illustrative examples follow. At the high-mountain Izaña Atmospheric Observatory in Tenerife, Spain, Garcia et al. [

10] successfully reconstructed an 80-year time series of daily global solar irradiation from sunshine duration measurements collected between 1933 and 1991. This reconstruction was achieved using an A–P equation calibrated with pyranometric data recorded from 1992 to 2013 [

10]. Reference [

11] reports the use of a non-linear Ångström–Prescott-type equation to estimate daily to decadal variations in solar irradiation from sunshine duration measurements. The A–P equation has been applied to investigate the drivers of solar dimming and brightening at the Earth’s surface during the second half of the 20th century [

12]. The study [

13] examines how global dimming and brightening influence the estimation of A-P coefficients using geographically weighted regression across China. The authors report pronounced differences in the coefficients during the dimming and brightening periods. These findings indicate that the transition from darker to brighter atmospheric conditions substantially affect the estimation of solar irradiation from sunshine duration. Reference [

14] analyzes the evolution of the relationship between solar radiation and sunshine duration in six major urban areas of China. The study [

15] investigates the variability of atmospheric transmittance derived from radiometric records by applying the A–P equation.

Within this broader context, the present work contributes to a relatively underexplored area by emphasizing the relevance of the A–P equation in atmospheric climatology. Our approach departs from previous studies by providing a self-consistent derivation of the annual average atmospheric transparency at a given location, based on the A–P equation. What this study adds is a self-consistent reformulation of the annual average atmospheric transparency at a given location starting from the monthly A–P equation. In deriving the revised equation, the relative sunshine duration is naturally replaced by an effective relative sunshine duration weighted by the solar energy at the top of the atmosphere. The revised A–P equation, innovatively coupled with Gaussian process regression, is validated as a powerful tool for analyzing and predicting atmospheric transparency. Using this tool, a ten-year probabilistic prediction is produced for four atmospheric parameters: annual clear-sky atmospheric transparency, cloud transmittance, mean atmospheric transparency, and effective relative sunshine duration.

The reminder of this work is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the revised A–P equation. In

Section 3, the equation is coupled with Gaussian process regression and validated as a predictor of annual mean atmospheric transparency.

Section 4 is devoted to presenting and analyzing the results concerning the prediction of atmospheric transmittance using the new tool. The main conclusions are summarized in

Section 5.

2. A Revised Formulation of the Ångström–Prescott Equation

The A–P equation is applied in practice mainly for estimation purposes. When the sunshine duration in a period is known, the A–P equation estimates the global solar irradiation in that period. As summarized in the Introduction, there are some attempts to use the A–P equation as a proxy in deriving atmospheric transparency. When studying atmospheric transparency climatology, the A–P equation cannot be applied directly because sunshine duration is unknown in the future. Moreover, the A–P equation typically operates with monthly sampled quantities. In climatological studies, monthly sampling is often inappropriate. Sampling over longer periods, such as a calendar year, is convenient. But the empirical development of a proper A–P equation with annual sampling comes with a major deficiency in terms of the climatology of atmospheric transparency and cloud transmittance. The coefficients a and b in Equation (2) are typically derived from past records, kept fixed, and then applied in future years. Since and are expressed in terms of the parameters a and b (Equations (3) and (4)), it follows that the A–P equation with annual sampling will always assume a constant value of the two transmittances in the future. This prevents the A–P equation from being used on an annual basis in climatological studies aimed at evaluating changes in atmospheric transparency.

This study introduces a new annual formulation of the A–P equation derived from its monthly version. Although its formal structure is preserved, the revised formulation departs from the equation’s conventional purpose of estimating solar energy. In this revised form, the equation acquires a new functionality, enabling its use in the climatological prediction of atmospheric transparency and cloud transmittance. The new equation is mathematically derived from the standard monthly sampled A–P equation.

where the subscript

m indicates monthly sampling. Based on

and

measured in the year

y, the linear regression coefficients

and

are estimated. The subscript

y emphasizes that

and

are natively linked to measurements from year

y and only from year

y. Equation (5) can be written for each month

m of year

y. By summing over the 12 months of year

y, the following expression is obtained.

Let the global solar irradiation at ground level in year

y be denoted by

, the extraterrestrial solar irradiation by

and the annual clearness index

. The physical quantity:

will be denoted herein as effective relative sunshine duration. Finally, Equation (6) can be written in a compact form as follows:

Equation (8) represents a reformulation of the annually sampled A–P equation, which is suitable for the climatological study of atmospheric transparency. The coefficients and are specific to year , thus allowing the evaluation of the mean cloudless atmospheric transparency and mean cloud transmittance for year . The clearness index provides an annual quantification of the mean atmospheric transmittance integrated over all-sky conditions.

The quantity (Equation (7)) introduces an innovative definition of the annual relative sunshine duration. is computed as the weighted average of the monthly relative sunshine durations, with monthly extraterrestrial irradiation as weight. The weights are calculated deterministically, repeating year after year. It is noteworthy that is an effective physical quantity that naturally captures the monthly variation in day length. assigns greater weight to the relative sunshine during summer months than during winter months.

In conclusion, Equation (8) is formally an A–P equation that encapsulates the atmospheric transparency characteristics of an entire year based on monthly measurements of relative sunshine. The derivation of Equation (8) shows that the transition from the monthly to the annual A–P formulation is self-consistent and requires no simplifying assumptions.

3. Validation of the Revised Ångström–Prescott Equation for All-Sky Atmospheric Transparency Prediction

In this section, the revised A–P equation is integrated with a machine learning technique for probabilistic time series forecasting, namely Gaussian process (GP) regression [

16]. The GP regression was chosen because it can effectively handle complex scenarios and small datasets. Unlike many machine learning models, such as neural networks that typically require large datasets, GPs can perform reliably even with limited training data. Further in this section, the database used in this study is described. Next, the Gaussian process regression is introduced. The section concludes with the presentation of a newly assembled tool for predicting annual average atmospheric transmittance and with its validation against measurements.

3.1. Database

This study was conducted with radiometric data from the World Radiation Data Center (WRDC) [

17], the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) central repository for solar radiation observations. Located at the Main Geophysical Observatory in St. Petersburg, Russia, WRDC applies standardized quality-control procedures, and requests confirmation from participating stations to ensure the reliability of the archived data. Monthly averages of daily global solar irradiation and monthly averages of relative sunshine, measured over periods exceeding 30 years at 14 stations across Europe, are used in this study.

Table 1 lists these stations together with their geographical coordinates, altitude, observation period, record length, and climate. Additional details regarding instrumentation and calibration procedures can be found on the WRDC website [

17].

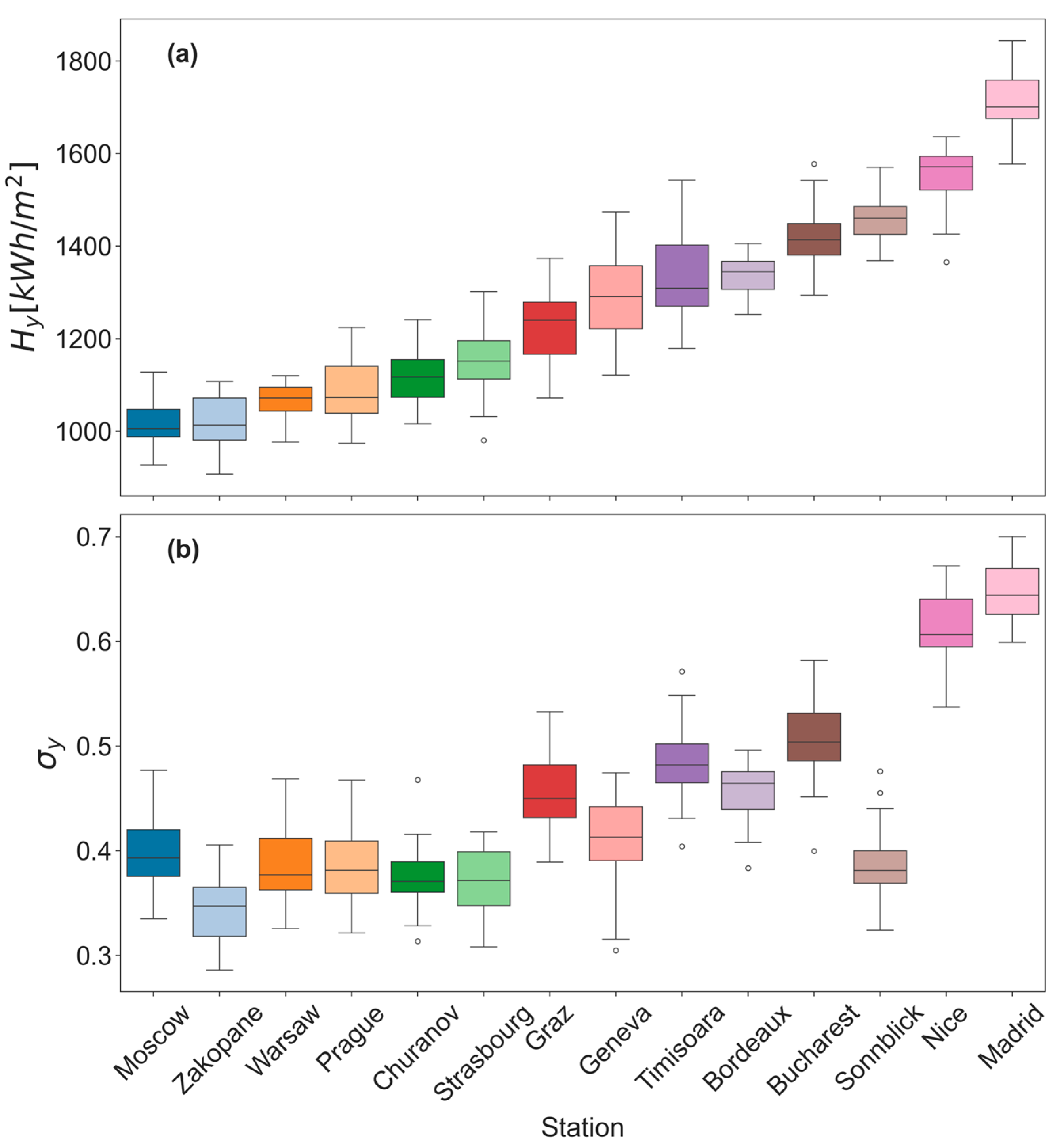

Since this study focuses on an annual-scale analysis of physical quantities related to mean atmospheric transparency,

Figure 1 provides boxplot representations of the relevant datasets. Specifically, it shows statistical summaries of the annual global solar irradiation

and the annual relative sunshine duration

for each station. A wide range of annually collectable solar energy on a horizontal surface of one square meter is observed, from just above 1000 kWh/m

2 in Moscow to approximately 1700 kWh/m

2 in Madrid. The variability of the

series differs across stations, with the smallest variability recorded in Warsaw and the largest in Timișoara.

As seen in

Figure 1, the stations are ordered by increasing annual solar irradiation

. If we consider an ideal A–P relationship with general applicability across Europe, the annual relative sunshine duration

would be expected to follow the same monotonically increasing trend as

. A comparison between

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b shows that the overall trend is preserved, although monotonicity is partially disrupted in

Figure 1b. Local altitude appears to reduce the relative sunshine duration, as observed for stations such as Zakopane, Sonnblick, and even Geneva. Conversely, some stations exhibit higher-than-expected values of

, notably Moscow and Graz. These deviations are likely driven by differences in atmospheric transparency and cloud transmittance, which are physical quantities that this study aims to evaluate and predict.

Returning to the strictly descriptive interpretation of

Figure 1, the variability in

is generally similar across stations. Three exceptions stand out: Zakopane, Churanov, and Sonnblick. At these mountain stations, the annual relative sunshine duration is noticeably more stable, and is roughly half that of the other sites. Overall,

Figure 1 shows that the radiometric records from the stations selected for this study capture the European diversity in the local

series and in the local relationship between

and

.

3.2. Gaussian Process Regression

A GP regression is a non-parametric Bayesian method that treats the input–output relationship as a probability distribution over possible functions. By conditioning this distribution on observed data, the method produces predictions that naturally incorporate quantified uncertainty. GP regression models an unknown function by assuming that any finite set of its values follows a joint multivariate Gaussian distribution. GP is fully characterized by a mean function and a covariance function (kernel), with the latter encoding relationships among input points and capturing structural properties such as smoothness, periodicity, or broader correlation patterns. When observational data are incorporated, the GP framework updates the prior assumptions to yield a posterior distribution over plausible functions, thereby providing both point predictions and associated uncertainty estimates. In essence, a GP returns the posterior predictive mean and standard deviation for each forecasted value. The choice of kernel—and its associated hyperparameters, such as characteristic length-scale and variance—determines the model’s expressiveness and capacity to fit the underlying process. Commonly used kernels include the radial basis function (RBF), white-noise, and rational quadratic kernels. It is worth mentioning that the GP regression is already used in solar energy modeling [

19].

In this study, the GP regression is employed to produce long-term forecasts of four annually averaged quantities: all-sky atmospheric transparency, clear-sky atmospheric transparency, cloud transmittance, and effective relative sunshine duration. The corresponding time series are generated using the revised Ångström–Prescott equation. In our implementation, the initial kernel configuration used for all extrapolations consisted of the sum of the three previously mentioned components: the RBF, white-noise, and rational quadratic kernels. The characteristic length-scale parameter was initialized to 1, while the scale-mixture parameter of the rational quadratic kernel was set to 0.5.

An advantage of GP regression is its ability to naturally accommodate missing data by conditioning predictions exclusively on the available observations. As a result, future projections are primarily driven by the inferred long-term trend rather than by individual missing years. As noted in

Table 1, some stations have incomplete records; however, because the missing observations constitute only a small fraction of the historical dataset, their influence on the inferred past and future trends is expected to be limited.

3.3. Predictive Effectiveness

To evaluate the effectiveness of the revised A–P equation (Equation (8)) in climatological studies, its performance in predicting the annual mean atmospheric transparency was assessed. The test was conducted for each station in

Table 1, using data recorded during 2014–2023. For every station, observations from years preceding the test period were used to estimate the coefficients of the A–P equation.

Three predictive methods were evaluated as follows:

Method 1. Typical A-P equation. The equation was calibrated using multi-annual sampling of historical data and then applied to the test period. This approach estimates from annual relative sunshine measurements. In essence, it tests the intrinsic accuracy of the A-P formulation itself, and the resulting performance should be viewed as a benchmark.

Method 2. Annual clearness index and GP regression. The historical series of the clearness index was derived from direct annual solar irradiance measurements. GP regression was then applied to forecast future values and quantify the associated uncertainty, providing a clear view of potential variability.

Method 3. Revised A–P equation and GP regression. The revised A–P equation (Equation (8)) was used to generate the historical annual time series. GP regression was then applied to predict future values and quantify the associated uncertainty, just as in Method 2.

The results of testing the three

prediction methods are presented in

Table 2. The deterministic predictions from Method 1 are compared with the mean predictions of the probabilistic Methods 2 and 3 in terms of three statistical indicators: normalized root mean square error (

nRMSE), normalized mean bias error (

nMBE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). In addition, the probabilistic Methods 2 and 3 are further evaluated using specific probabilistic metrics, namely negative log predictive density (

NLPD) and Continuous Ranked Probability Score (

CRPS). All five performance indicators are defined next.

where

c and

m refer to the estimated and measured values of a physical quantity, respectively, while

M denotes the number of measurements.

For a Gaussian predictive distribution with mean

µ and variance

σ2,

NLPD is defined as follows:

Mean

CPRS for

M observations and

M predictive distributions is calculated as follows:

where the variable is

, Φ denotes the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution, and

ϕ denotes the probability density function (PDF) of the standard normal distribution.

Table 2 shows that the three methods achieve relatively similar accuracy in predicting

. The

nRMSE ranges from 0.0175, reached by Method 2 in Bordeaux near the Atlantic coast, to 0.0985, obtained by Method 1 in Geneva, a city surrounded by the Jura Mountains. The evaluation in terms of

MAPE is consistent with the evaluation based on

nRMSE. The lowest

MAPE value (

MAPE = 0.018) is reached by Method 2 in Bordeaux, while the highest (

MAPE = 0.0925) is obtained by Method 1 in Geneva. Overall, the statistical indicators show a good predictive performance for all three methods, with

nRMSE values falling within the following ranges: 0.0201 ≤

nRMSE ≤ 0.0985 for Method 1, 0.0175 ≤

nRMSE ≤ 0.0798 for Method 2, and 0.0192 ≤

nRMSE ≤ 0.0855 for Method 3. When focusing exclusively on the accuracy of Methods 2 and 3,

nRMSE and

MAPE show a very close similarity in predicting

. This behavior is confirmed by specific performance indicators in probabilistic prediction,

NLPD and

CRPS in

Table 2. In terms of the percentage

P of measurements falling within the 95% confidence interval at eight stations, the validation is 100%, meaning that all measurements fall within the confidence interval. At ten of the fourteen stations, Method 2 and Method 3 achieve the same percentage

P in

Table 2.

This observation is significant and adds robustness to the study. Whereas Method 2 applies GP regression directly to the annually measured time series, Method 3 applies the same regression technique to time series generated using the revised A–P equation. The close agreement between the two methods lends substantial support to the validity of the revised A–P equation (Equation (8)) in its entirety. This outcome enables the extension of the analysis and prediction to the coefficients of Equation (8), from which—using Equations (3) and (4)—one can forecast the annual mean clear-sky atmospheric transparency and the annual mean cloud transmittance, respectively. Additionally, the effective relative sunshine duration can also be predicted. Thus, Method 3 functions as a versatile tool for a detailed investigation of the variability and the expected long-term evolution of atmospheric transparency.

4. Predicting Atmospheric Transparency in Europe Using the Revised Ångström–Prescott Equation

This section illustrates the application of the revised A–P equation (Equation (8)) to the analysis and prediction of the four annual parameters characterizing atmospheric transparency: mean clear-sky atmospheric transparency

, mean cloud transmittance

, mean atmospheric transparency

, and effective relative sunshine duration

. For each station listed in

Table 1, the historical time series of

,

,

and

were generated using Equation (8). The GP regression was then applied to produce annual predictions for the next ten years.

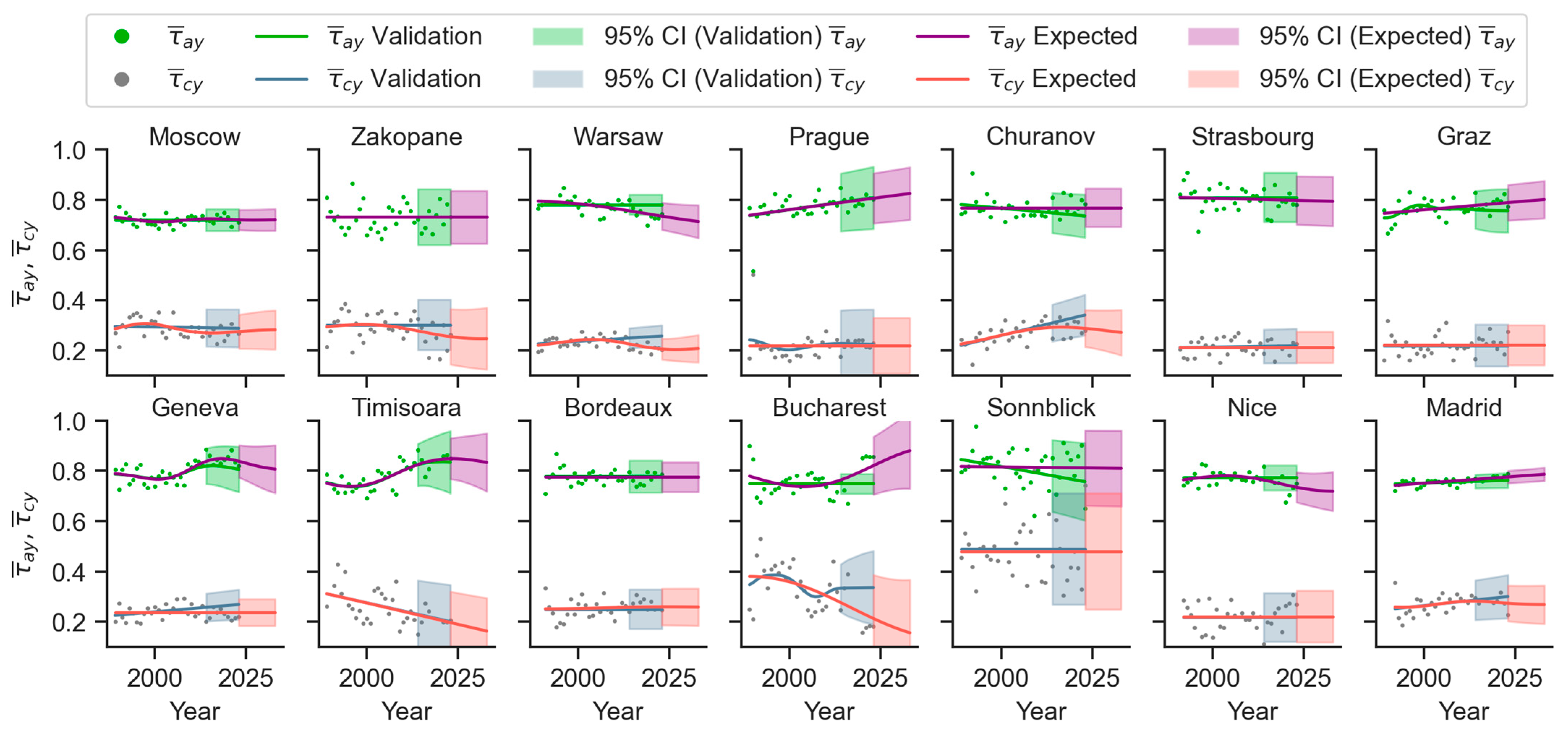

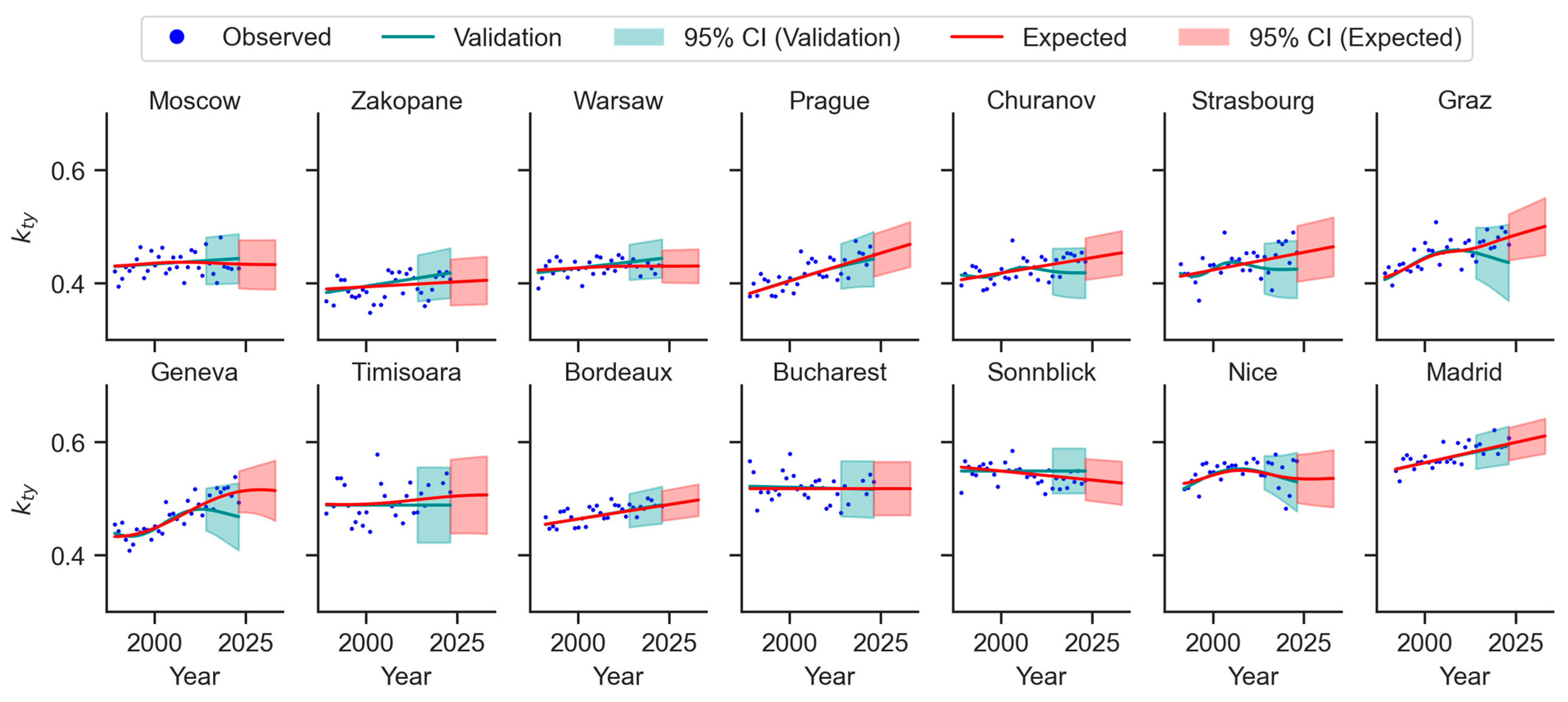

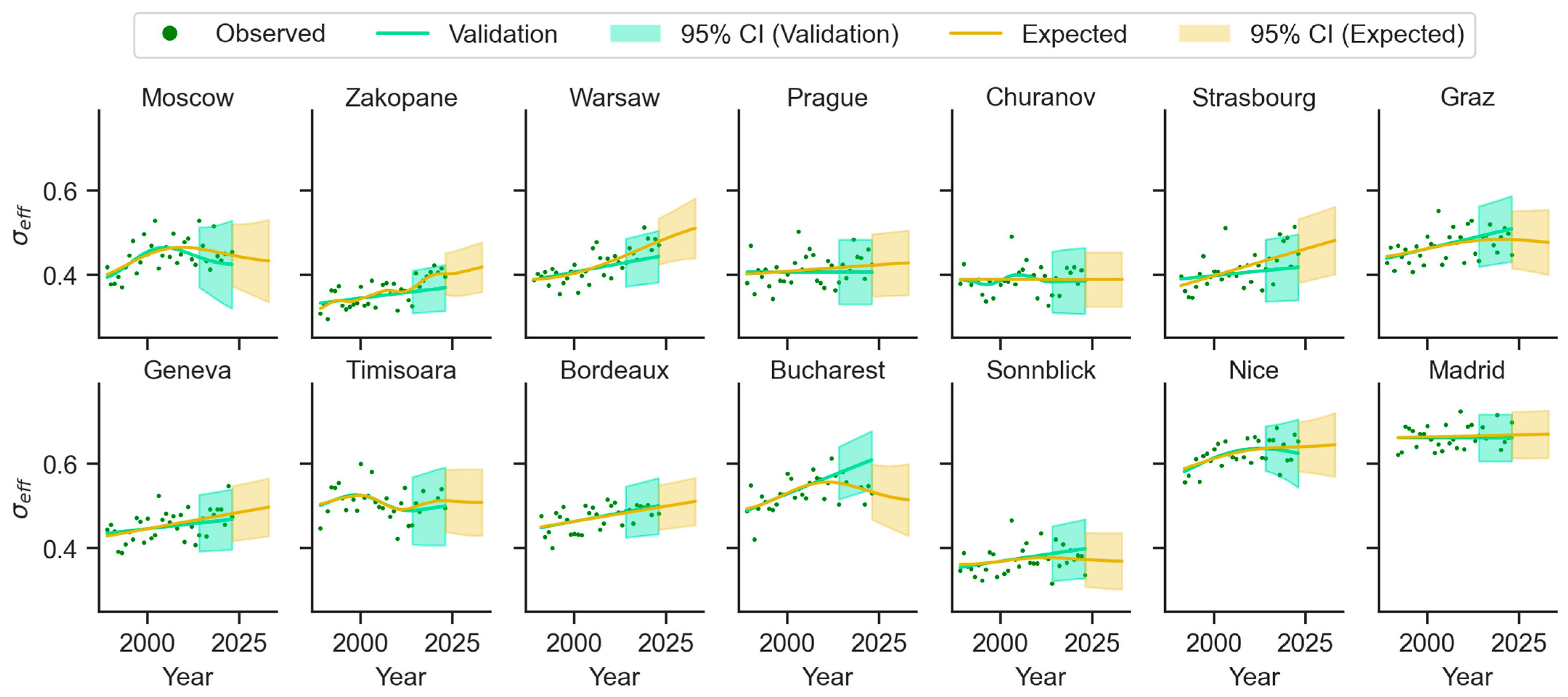

The resulting outcomes are illustrated in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, all adhering to an identical layout. Each panel corresponds to a specific station and presents the observed data, the model validation using the 2014–2023 interval as the test period, and the forecast for 2024–2033. In both the validation and forecasting phases, the predicted mean and the associated confidence interval are shown.

4.1. Climatology of the Cloudless Atmosphere Transparency and Cloud Transmittance

Figure 2 displays measured and predicted cloudless atmosphere transparency

and cloud transmittance

. Overall, the annual measurements of

and

fall within the predicted confidence intervals. For

exceptions occur at Bucharest and Warsaw, while for

the deviations appear at Bucharest, Warsaw (where the prediction uncertainty is the lowest), and Zakopane. The largest uncertainty is observed at Sonnblick. Madrid exhibits measurements that closely match the predicted mean and are associated with a narrow confidence interval. For the majority of the stations,

remains stable when projected into the future. Nice and Warsaw are predicted to experience lower

in the next decade. Prague, Graz, and Madrid are projected to undergo a linear increase in transparency, whereas Bucharest is characterized by a sharp increase accompanied by substantial uncertainty. Cloudless atmospheric transparency is strongly influenced by aerosol scattering. Accordingly, the observed differences in trends may be associated with changes in aerosol loading and properties. A detailed analysis of this relationship is beyond the scope of the present study and could be addressed in future work Cloud transmittance also remains largely steady. In Romania, the extrapolation indicates lower cloud transmittance at Timișoara and Bucharest, with high associated uncertainty and unpredictable lower boundary. At higher-altitude locations such as Zakopane and Churanov, a slight decrease in

is projected over the next 10 years, while Sonnblick exhibits extremely high prediction uncertainty, with clouds predicted to be more transparent than at any other station.

The projections for cloudless atmosphere transparency and cloud transmittance for the end of the forecast period (year 2033) are provided for each station in

Table 3. Each prediction is presented under three scenarios: medium (predicted mean), minimum (mean − 1.96·

SD), and maximum (mean + 1.96·

SD).

4.2. Climatology of the Mean Atmospheric Transparency

Figure 3 presents the measured and predicted mean atmospheric transparency

. The validation of the revised A–P equation for predicting

was previously presented and discussed in detail in

Section 3.3.

Figure 3 graphically summarizes the validation results in a layout consistent with

Figure 2. The confidence intervals produced by the GP regression encompass most of the measured values. The training period strongly influences extrapolation accuracy, as illustrated at Graz and Geneva, where the mean prediction substantially underestimates

. A key advantage of probabilistic GP regression is that the confidence interval adequately captures the underlying trend, even when the predicted mean deviates considerably from observations. Alongside the validation result, each panel in

Figure 3 presents, in probabilistic terms, the prediction for the period 2024–2033. For all stations, the mean atmospheric transparency

is predicted to remain stable or increase steadily over the entire period, with the exception of Sonnblick. It is worth noting that Sonnblick is the only station situated at an altitude above 3000 m a.s.l. and characterized by an Arctic climate, which may contribute to the observed difference in the mean atmospheric transparency trend. A persistent upward trend in atmospheric transparency over the past 35 years is evident in Prague, Bordeaux, and Madrid, and is expected to continue. The highest prediction uncertainty is found at Timisoara, while Bordeaux exhibits the lowest. The detailed projection of yearly mean atmospheric transparency at the end of the forecast period (2033) is provided for each station in

Table 3.

4.3. Climatology of Relative Sunshine

Figure 4 presents the measured and predicted effective relative sunshine duration

. Visual inspection of the validation period in each panel indicates that the annual

measurements fall within the predicted confidence intervals. In contrast to atmospheric transparency, the effective relative sunshine duration is more strongly constrained by the geographical setting of each radiometric station. The lowest values occur at the mountain stations Zakopane, Churanov, and Sonnblick, where the annual

σeff generally remains below 0.4. The highest values are recorded at Nice and Madrid, where annual

clusters around values exceeding 0.6.

During the validation period (2014–2023), most measurements fall within the confidence interval of the GP regression. Although the temporal evolution of is more complex than that of the atmospheric transparency, the effective relative sunshine duration is projected to remain stable or exhibit a slight increase over the next decade (2024–2033). Minor decreases in are anticipated only for Moscow, Graz (to a marginal extent), and Bucharest. The amplitude of predictive uncertainty shows less variability than that of the atmospheric transparency discussed in the previous subsections, reflecting the more intricate temporal behavior of .

5. Conclusions

In this study, the Ångström–Prescott equation is reexamined with the aim of deriving information on atmospheric climatology from radiometric measurements. A survey of the literature indicates that only a limited number of studies have addressed this topic. An annual formulation of the Ångström–Prescott equation (Equation (8)) is proposed, together with a self-consistent derivation. This formulation shifts the role of the equation from estimating solar irradiation to predicting long-term atmospheric transparency. The revised formulation naturally introduces an annual effective relative sunshine duration that places greater weight on relative sunshine during summer than during winter. This approach facilitates a more accurate representation of the seasonal variations in atmospheric conditions. To achieve predictive capability, the revised Ångström–Prescott equation is coupled with Gaussian Process regression. This combination yielded a robust framework for probabilistic predictions of atmospheric transparency. The Ångström–Prescott equation provides historical annual time series of the clearness index, while the Gaussian process regression model estimates future values and quantifies the associated uncertainty.

The innovative combination of the revised Ångström–Prescott equation and Gaussian process regression was validated as a powerful tool for long-term predictions of four atmospheric parameters: clear-sky atmospheric transparency, cloud transmittance, all-sky atmospheric transparency, and effective relative sunshine duration. The validation was performed using radiometric data collected at 14 stations across Europe for the period 1989–2023. The performance was assessed specifically for the interval 2014–2023. The results demonstrated that the revised equation is effective in predicting the mean cloudless atmospheric transparency, mean cloud transmittance, mean atmospheric transparency, and effective relative sunshine duration. For example, when predicting the annual clearness index, the normalized root mean square error ranges from 0.0192 to 0.0855 across all stations.

As an application of the proposed method, predictions for the upcoming decade (2024–2033) were generated for all stations. These predictions indicate that the all-sky atmospheric transparency is expected to remain stable or increase slightly at most stations. A particularly marked upward trend was identified at the stations of Prague, Bordeaux, and Madrid, and is expected to persist.

Overall, this study proposes a new methodological framework for examining atmospheric climatology. The predictive approach offers potential utility in climate research by improving the understanding of atmospheric transparency and its long-term evolution. Furthermore, the revised Ångström–Prescott equation may serve as a tool for investigating the drivers of solar dimming and brightening, thereby providing insight into the factors that influence atmospheric transparency.

The revised equation, coupled with Gaussian process regression, was tested at stations located in Europe, which may be regarded as a limitation of the present study. Comprehensive validation can only be achieved through external testing of the proposed method, including applications in harsher environments.

Future work will be devoted to investigating correlations between long-term aerosol loading trends and mean cloudless atmospheric transparency, mean cloud transmittance, mean atmospheric transparency, and effective relative sunshine duration. Although aerosols directly affect only mean cloudless atmospheric transparency, the proposed method enables the investigation of more subtle links between aerosol variability and all four parameters.