Assessment of Accuracy of COSMIC and KOMPSAT GNSS Radio Occultation Temperature and Pressure Measurements over the Philippines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Method

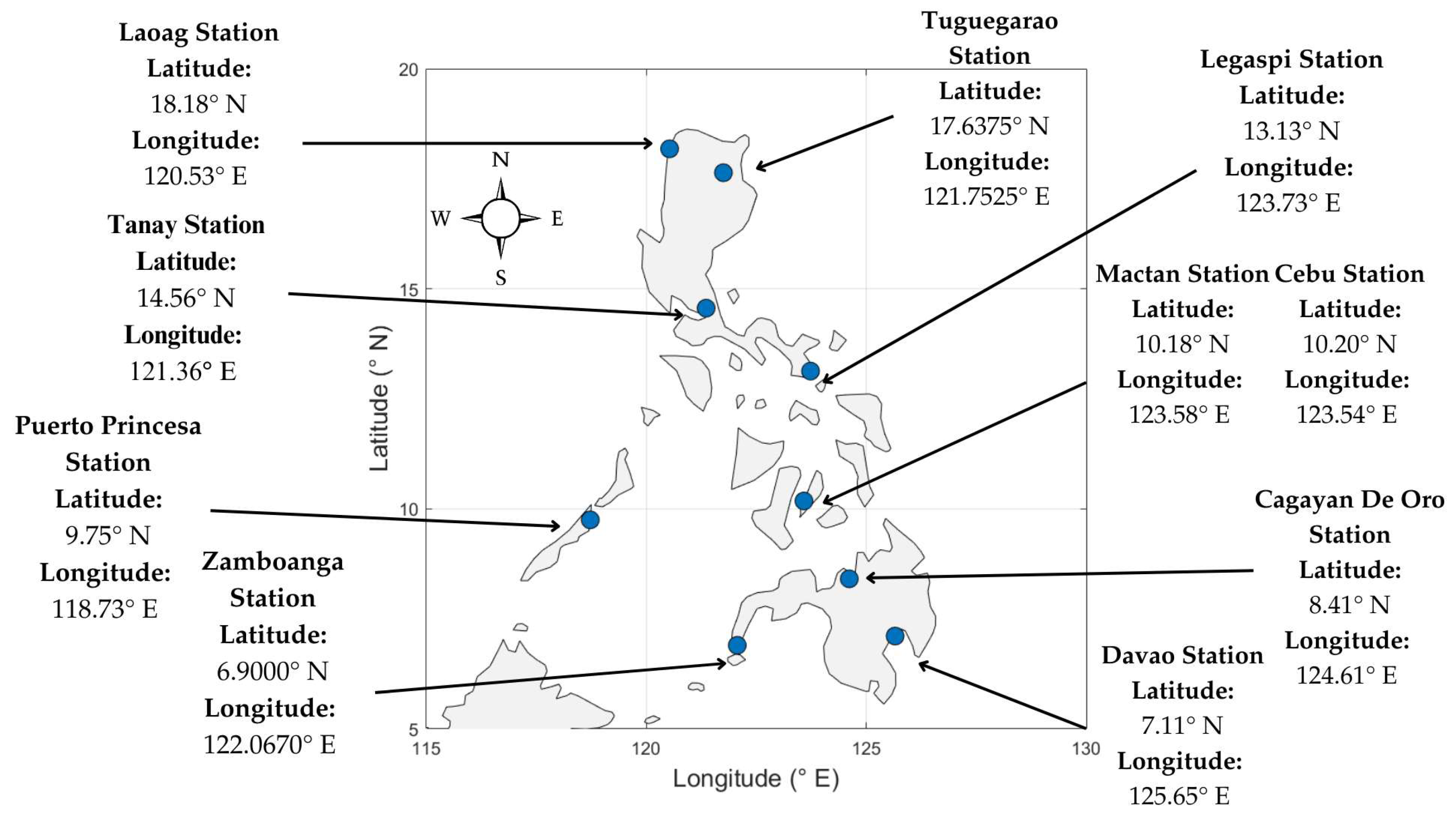

2.1. Radiosonde

2.2. COSMIC-2 and KOMPSAT-5

2.3. Collocation and Evaluation of RO Points with Radiosonde Profiles

2.4. Seasonal Variation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. COSMIC Versus Radiosonde Comparison

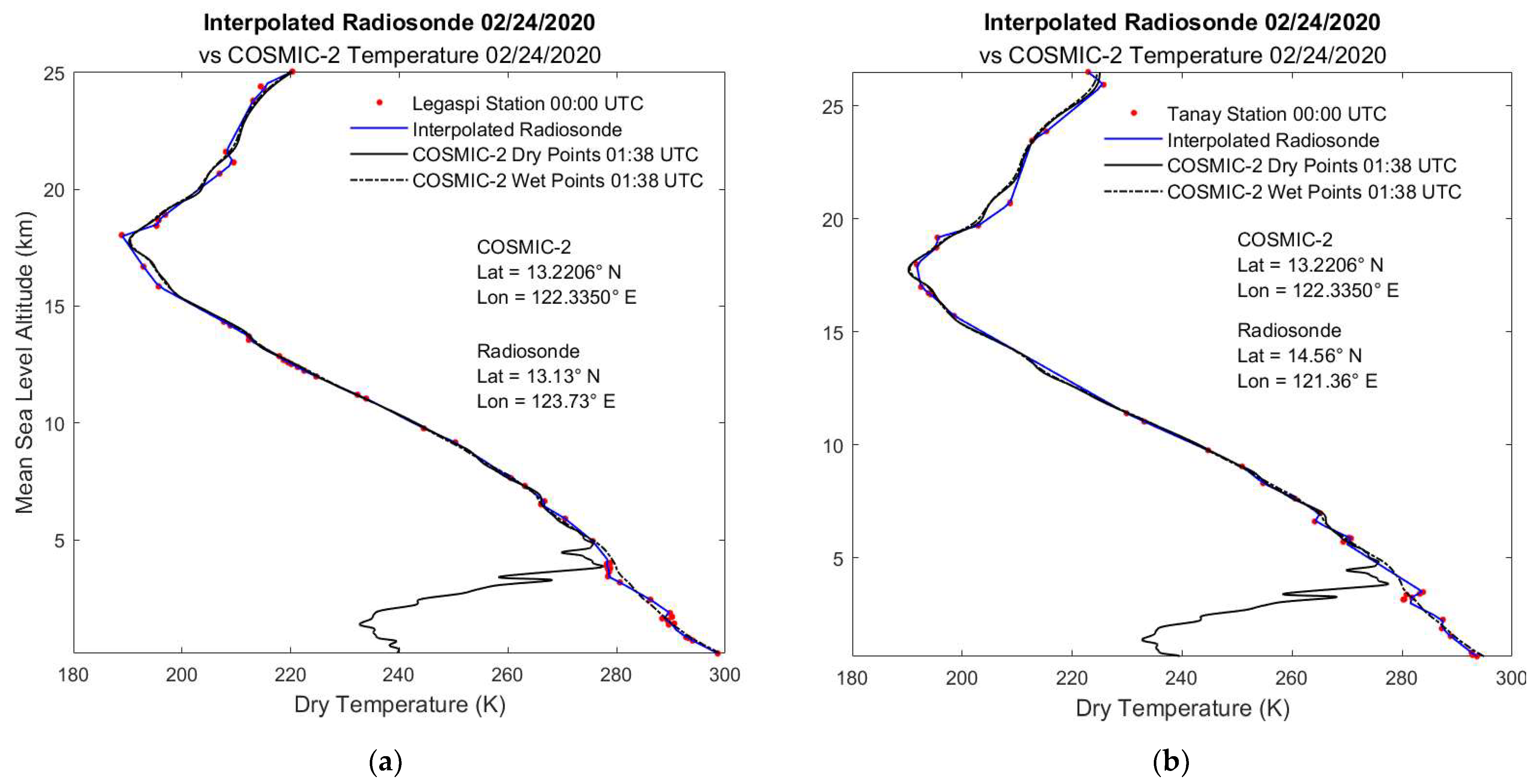

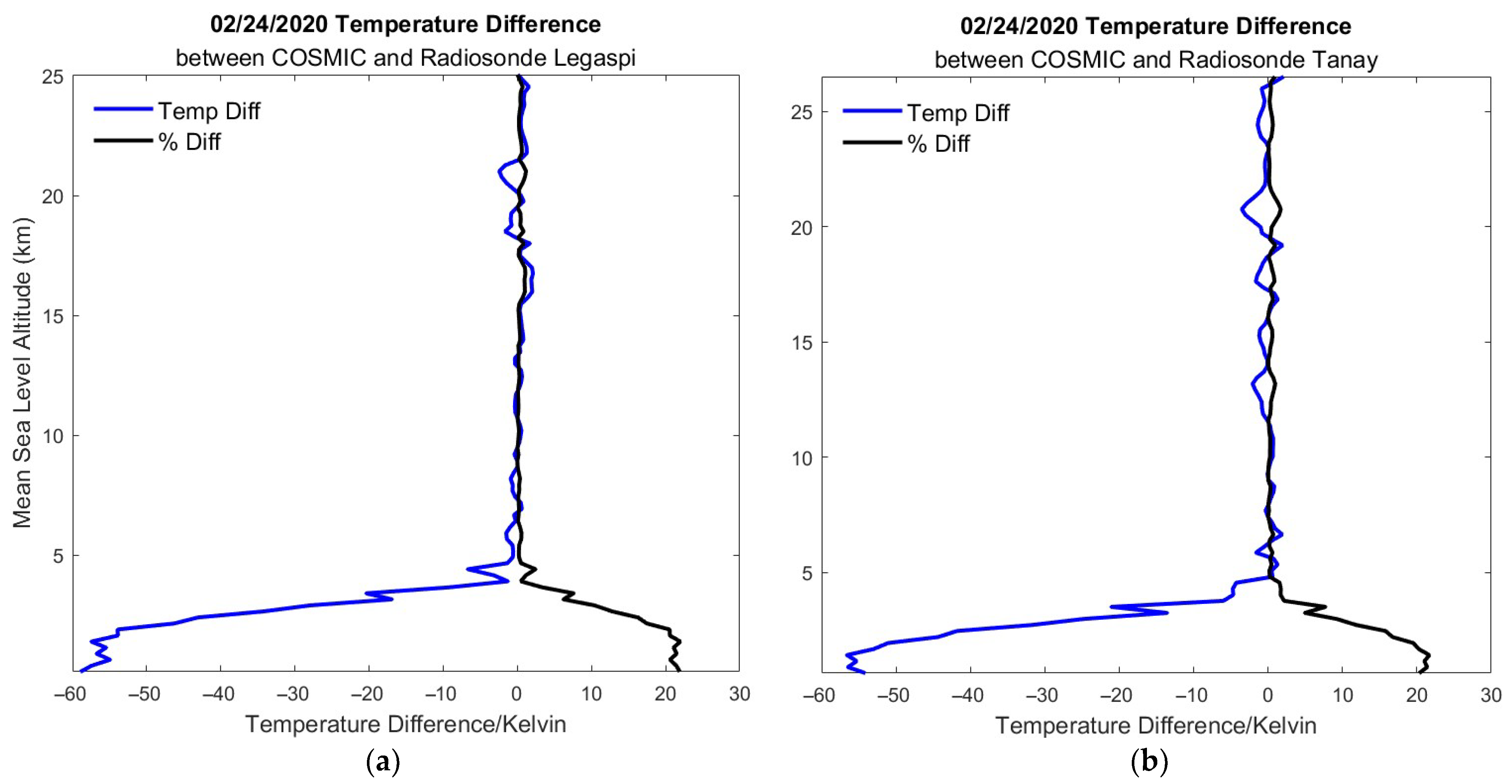

3.1.1. COSMIC v. Radiosonde Temperature

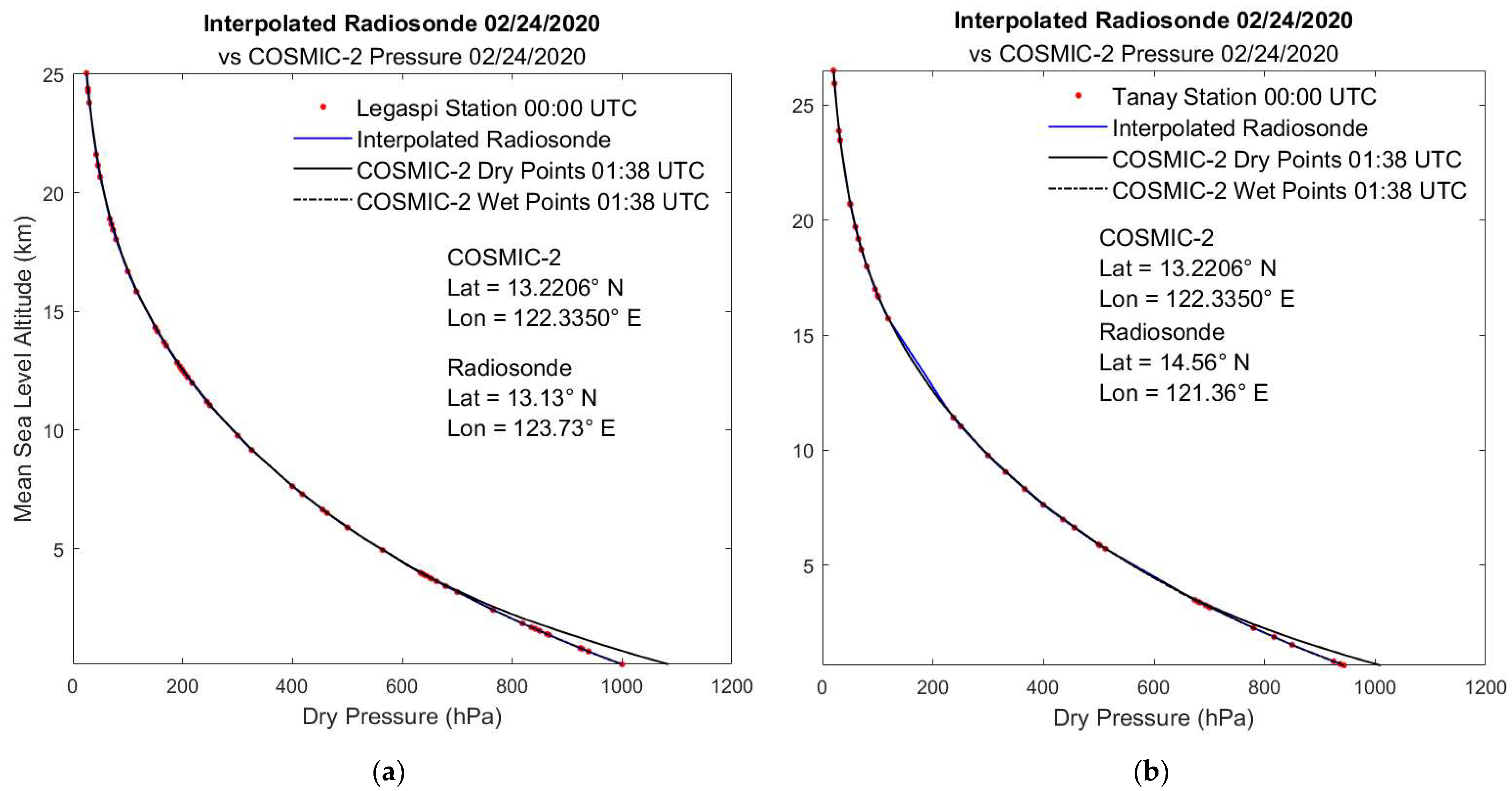

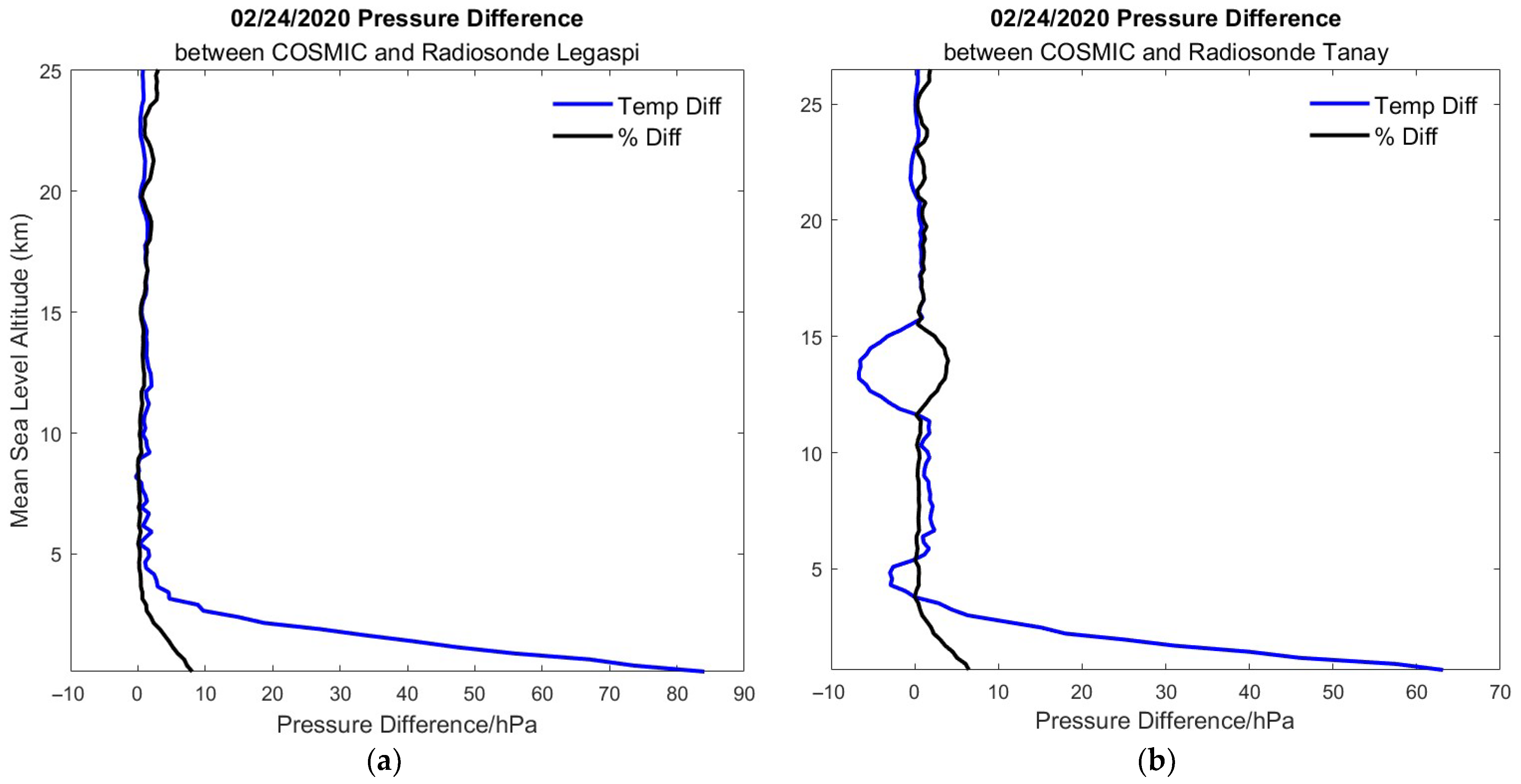

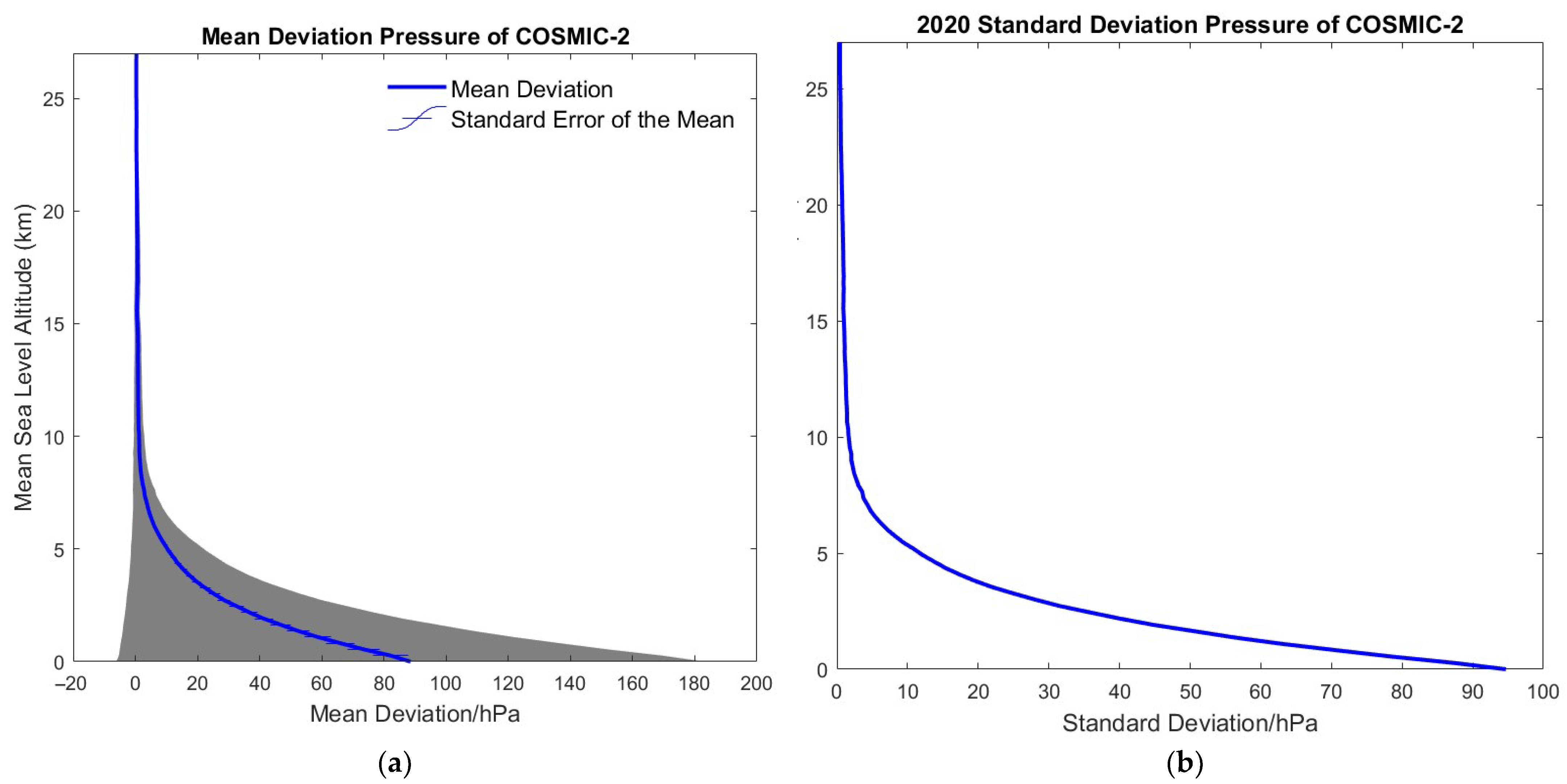

3.1.2. COSMIC v. Radiosonde Pressure

3.2. KOMPSAT Versus Radiosonde Comparison

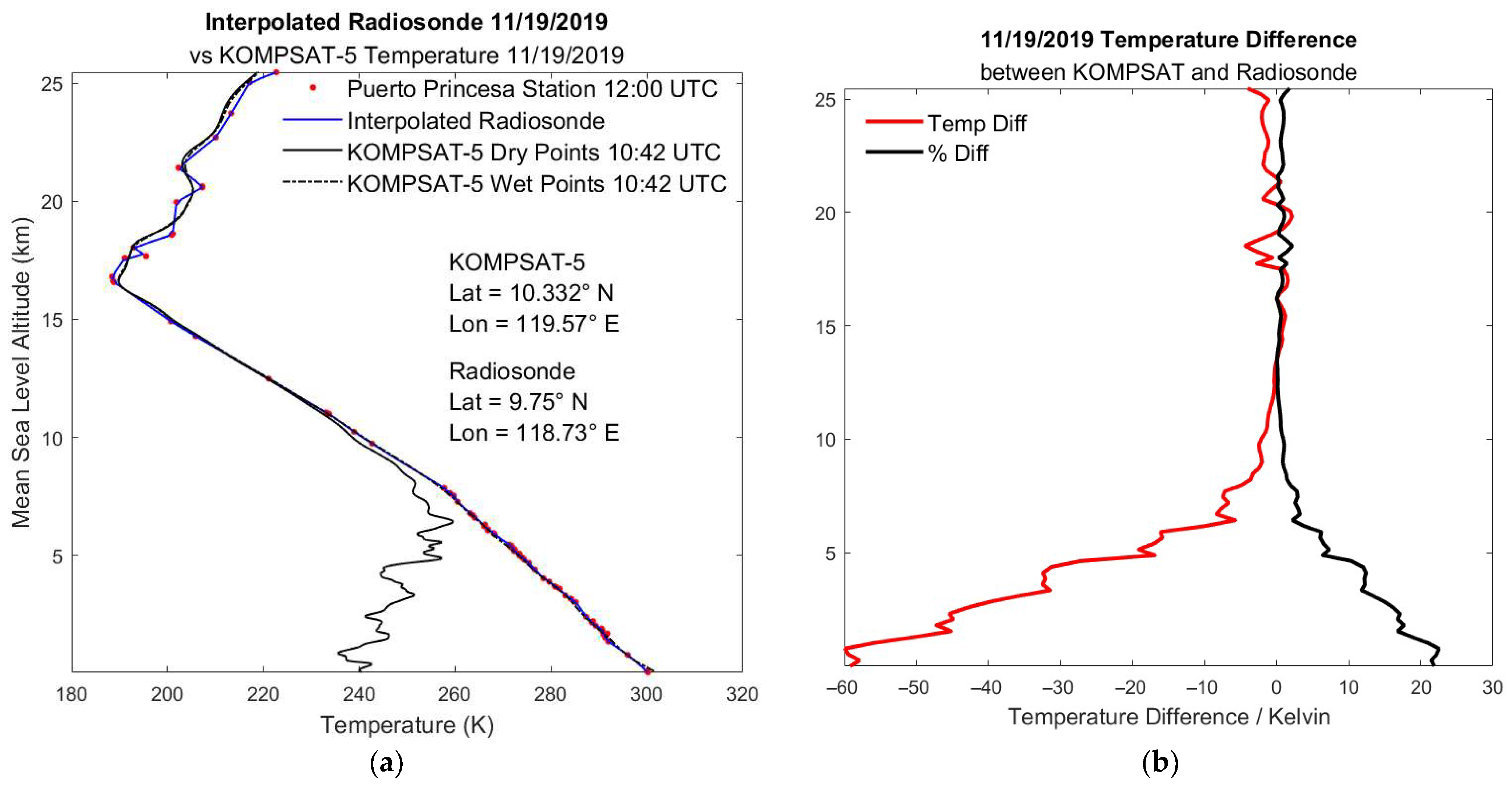

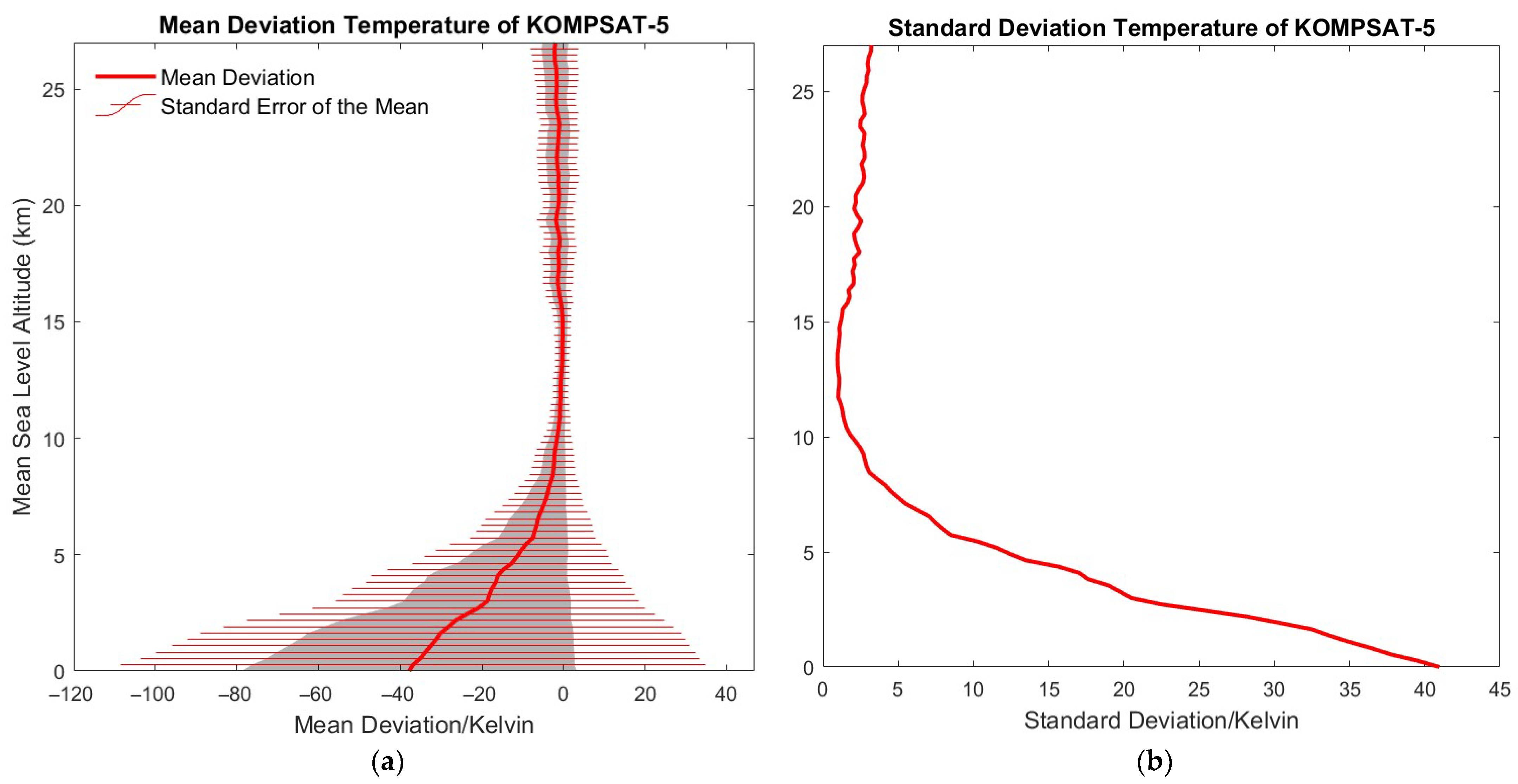

3.2.1. KOMPSAT v. Radiosonde Temperature

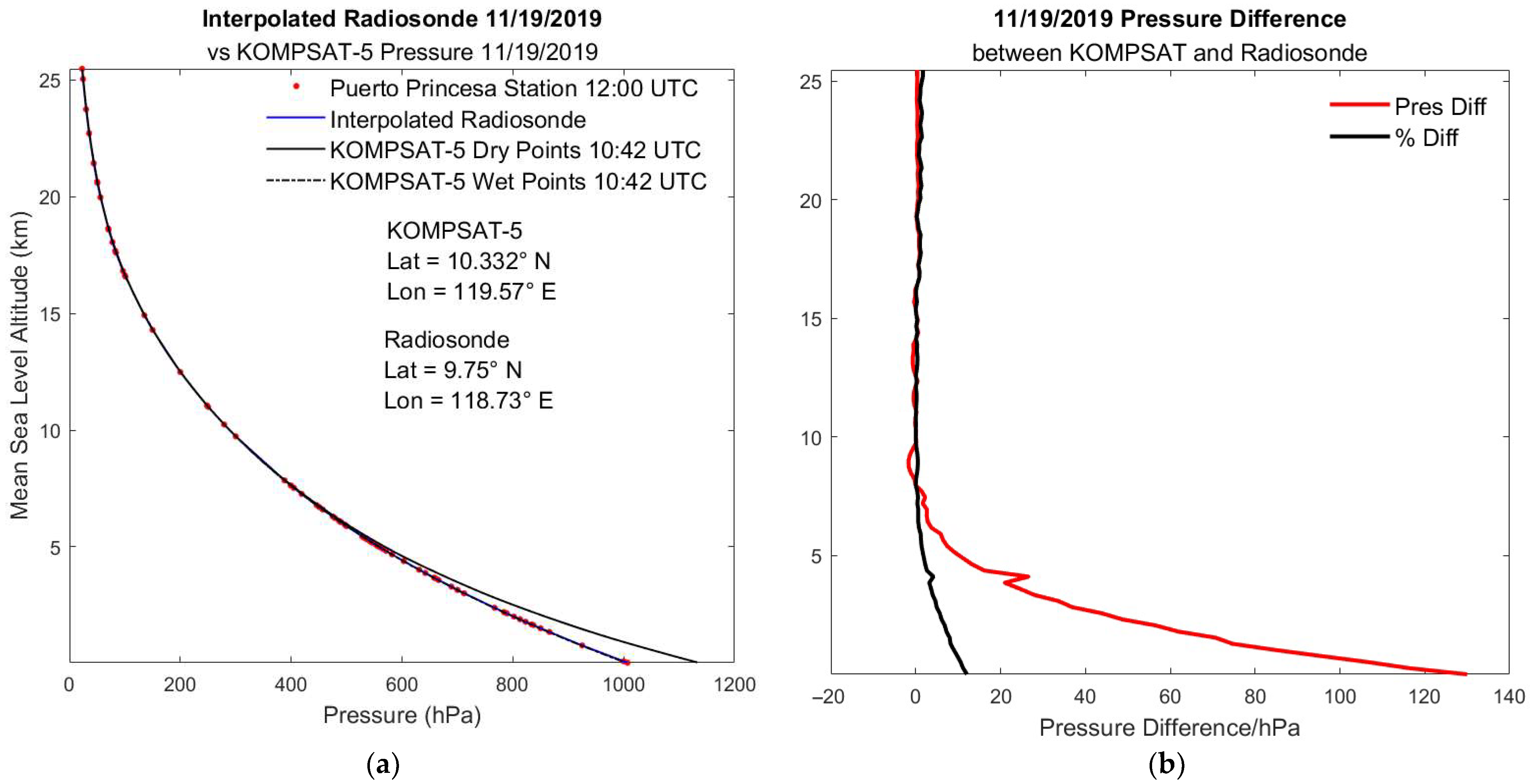

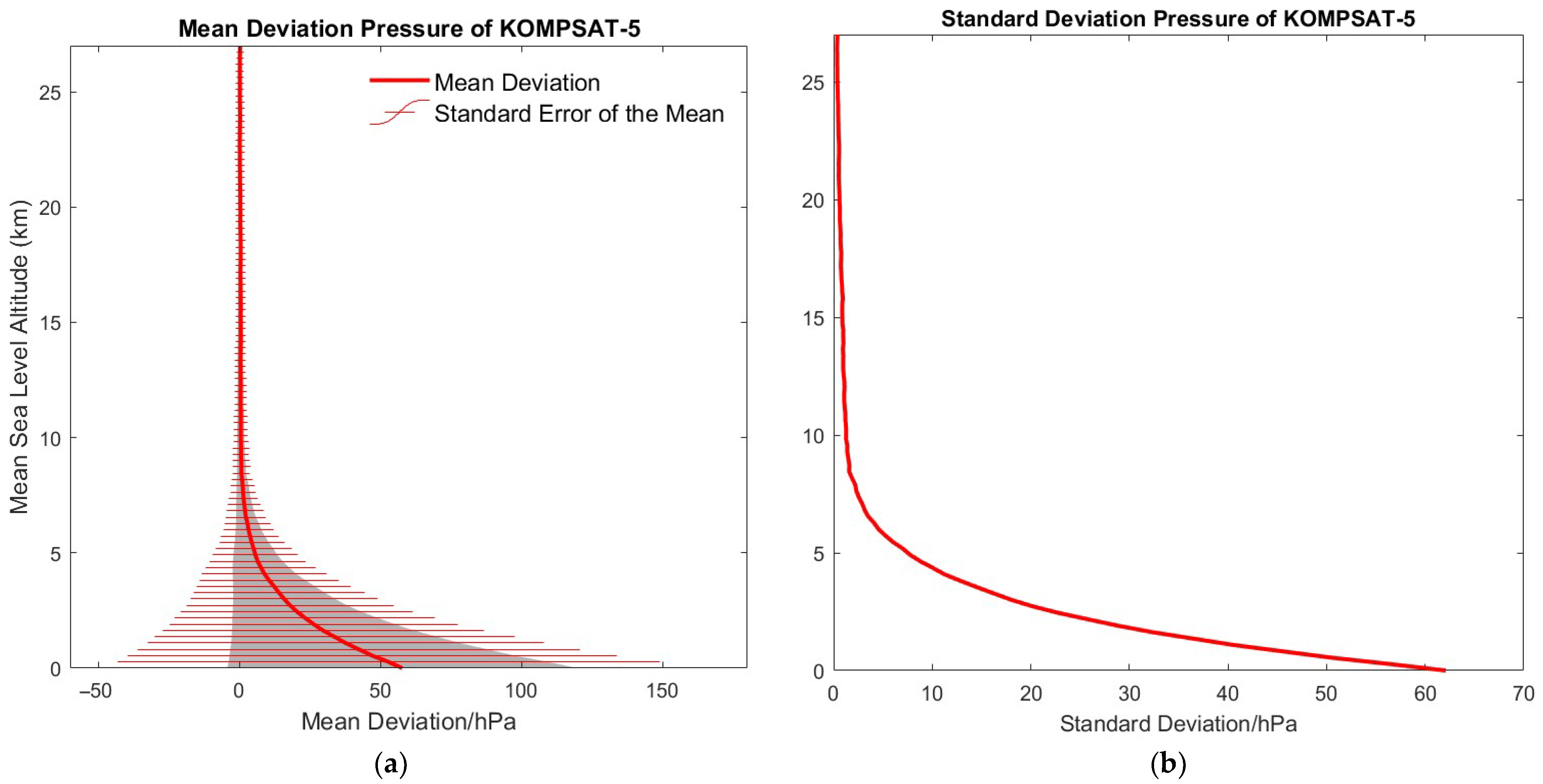

3.2.2. KOMPSAT v. Radiosonde Pressure

3.3. Seasonal Comparison

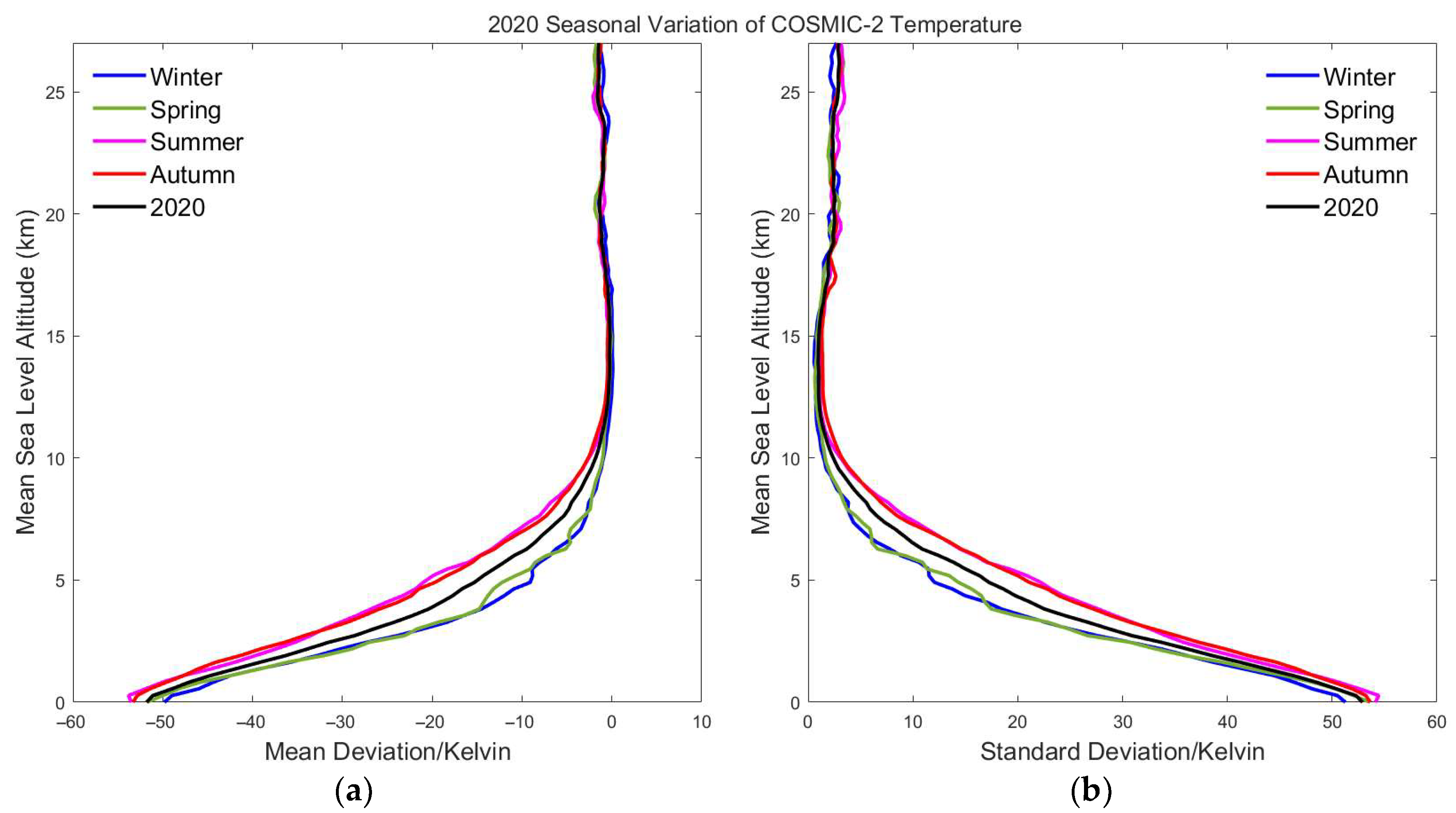

3.3.1. COSMIC v. Radiosonde

Temperature

Pressure

3.3.2. KOMPSAT v. Radiosonde

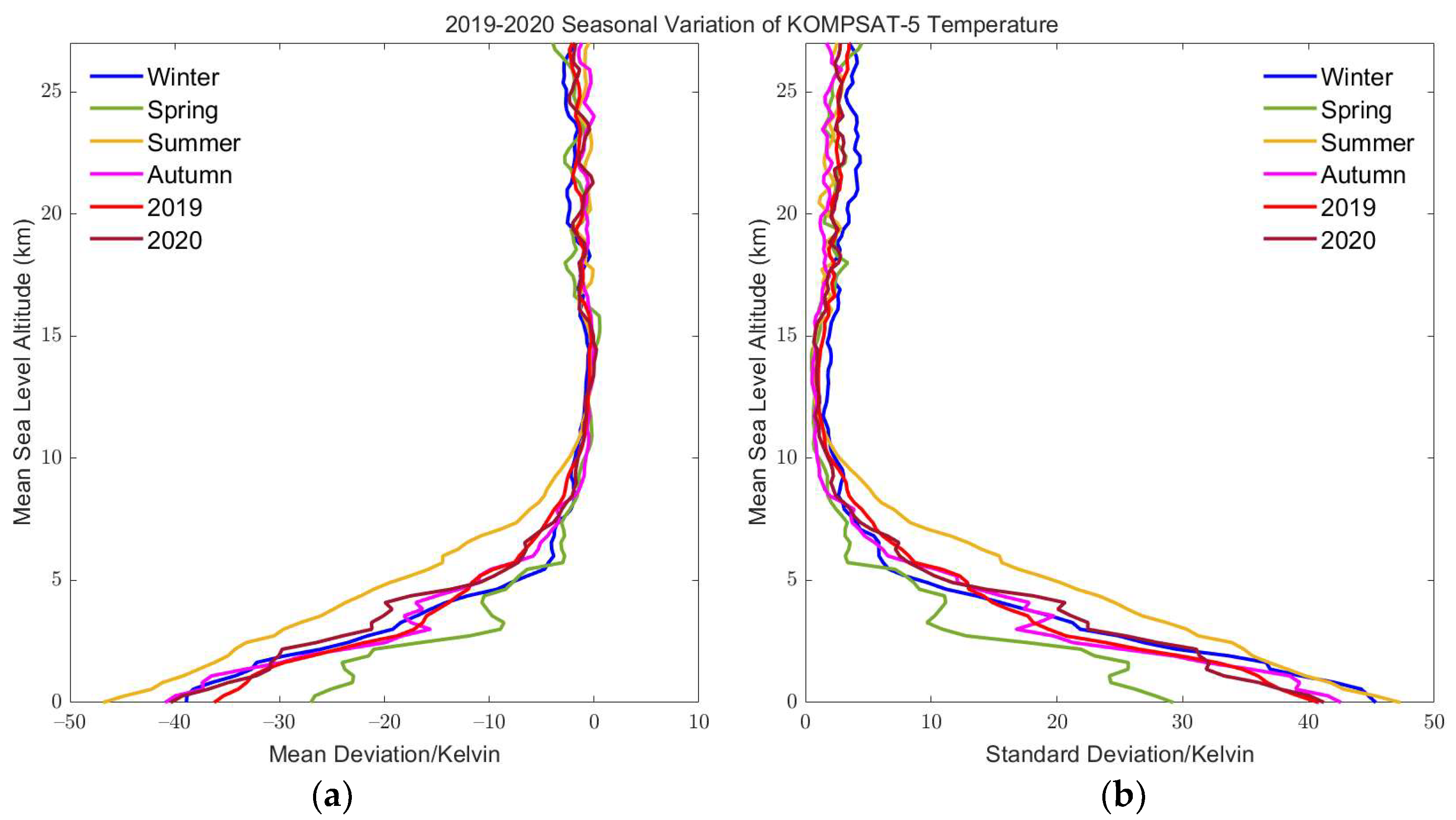

Temperature

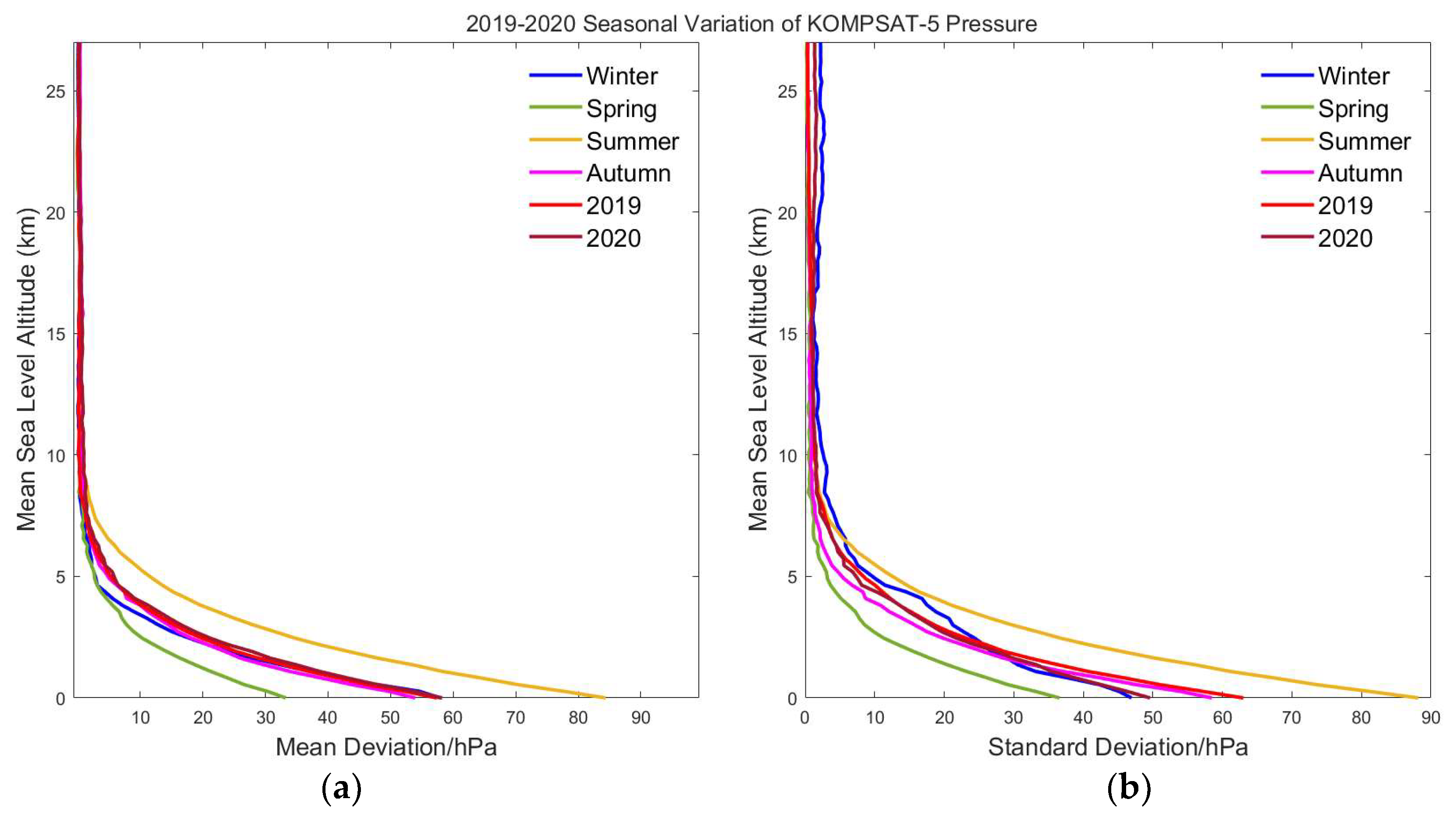

Pressure

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GNSS | Global Navigational Satellite System |

| RO | Radio Occultation |

| LEO | Low-Earth Orbit |

| COSMIC | The Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere and Climate |

| KOMPSAT | Korean Multi-Purpose Satellite |

References

- Durre, I.; Vose, R.S.; Wuertz, D.B. Overview of the Integrated Global Radiosonde Archive. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursinski, E.R. The GPS Radio Occultation Concept: Theoretical Performance and Initial Results. Bachelor’s Thesis, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursinski, E.R.; Hajj, G.A.; Bertiger, W.I.; Leroy, S.S.; Meehan, T.K.; Romans, L.J.; Schofield, J.T.; McCleese, D.J.; Melbourne, W.G.; Thornton, C.L.; et al. Initial results of radio occultation observations of Earth’s atmosphere using the global positioning system. Science 1996, 271, 1107–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, R.; Rocken, C.; Solheim, F.; Exner, M.; Schreiner, W.; Anthes, R.; Feng, D.; Herman, B.; Gorbunov, M.; Sokolovskiy, S.; et al. GPS Sounding of the Atmosphere from Low Earth Orbit: Preliminary Results. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1996, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lee, J.; Yoon, H.; Morton, Y.J.; Saltman, A. Performance Assessment of Radio Occultation Data from GeoOptics by Comparing with COSMIC Data. Earth Planets Space 2022, 74, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-P.; Zhou, X.; Shao, X.; Zhang, B.; Adhikari, L.; Kireev, S.; He, Y.; Yoe, J.G.; Xia-Serafino, W.; Lynch, E. Initial assessment of the COSMIC-2/FORMOSAT-7 neutral atmosphere data quality in NESDIS/STAR using in situ and satellite data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, D.; Yuan, H. Comparative Assessment of SpIRE and COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation Data Quality. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, W.S.; Weiss, J.P.; Anthes, R.A.; Braun, J.; Chu, V.; Fong, J.; Hunt, D.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Meehan, T.; Serafino, W.; et al. COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation Constellation: First Results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL086841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumul, G.P.; Cruz, N.A.; Servando, N.T.; Dimalanta, C.B. Extreme weather events and related disasters in the Philippines, 2004–2008: A sign of what climate change will mean? Disasters 2010, 35, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinco, T.A.; de Guzman, R.G.; Ortiz, A.M.D.; Delfino, R.J.P.; Lasco, R.D.; Hilario, F.D.; Juanillo, E.L.; Barba, R.; Ares, E.D. Observed trends and impacts of tropical cyclones in the Philippines. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 4638–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, B.; Camargo, S.J. The seasonally-varying influence of ENSO on rainfall and tropical cyclone activity in the Philippines. Clim. Dyn. 2008, 32, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.Q.; Sheng, Z.; Shi, H.Q.; Yi, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, E.Z. Comparative Assessment of COSMIC Radio Occultation Data and TIMED/SABER Satellite Data over China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2015, 54, 1931–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Biadeglgne, B.; Wu, F. A Comparison of Atmospheric Temperature and Moisture Profiles Derived from GPS Radio Occultation and Radiosonde in Australia. IEICE Tech. Rep. 2007, 107, 7–12. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1520009408590533632 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Wickert, J.; Reigber, C.; Beyerle, G.; König, R.; Marquardt, C.; Schmidt, T.; Grunwaldt, L.; Galas, R.; Meehan, T.K.; Melbourne, W.G.; et al. Atmosphere Sounding by GPS Radio Occultation: First Results from CHAMP. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 3263–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, R.G.; Macalalad, E.P. Monthly Observations of Cold-Point Tropopause Temperature and Height for 2008 in the Philippines Using COSMIC GPS Radio Occultations. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1936, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Liu, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hsu, S.-C.; Li, H.-W.; Lin, P.-H.; Cheng, J.-P.; Huang, C.-Y. An Analysis Study of FORMOSAT-7/COSMIC-2 Radio Occultation Data in the Troposphere. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Rohden, C.; Sommer, M.; Naebert, T.; Motuz, V.; Dirksen, R.J. Laboratory Characterisation of the Radiation Temperature Error of Radiosondes and Its Application to the GRUAN Data Processing for the Vaisala RS41. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randel, W.J.; Wu, F. Biases in Stratospheric and Tropospheric Temperature Trends Derived from Historical Radiosonde Data. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 2094–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Ho, S.; Chen, H.; Zhou, X.; Hunt, D.; Kuo, Y. Assessment of Radiosonde Temperature Measurements in the Upper Troposphere and Lower Stratosphere Using COSMIC Radio Occultation Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, 2009GL038712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Fu, E.; Silcock, D.; Wang, Y.; Kuleshov, Y. An Investigation of Atmospheric Temperature Profiles in the Australian Region Using Collocated GPS Radio Occultation and Radiosonde Data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2011, 4, 2087–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Reale, A.; Seidel, D.J.; Hunt, D.C. Comparing Radiosonde and COSMIC Atmospheric Profile Data to Quantify Differences among Radiosonde Types and the Effects of Imperfect Collocation on Comparison Statistics. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, 2010JD014457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Season | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month Division | D, J, F | M, A, M | J, J, A | S, O, N |

| Matching Pairs (KOMPSAT-5, 2019–2020) | 13 | 13 | 23 | 22 |

| Matching Pairs (COSMIC-2, 2020) | 54 | 44 | 62 | 73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Descalzo, K.P.A.; Macalalad, E.P. Assessment of Accuracy of COSMIC and KOMPSAT GNSS Radio Occultation Temperature and Pressure Measurements over the Philippines. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111285

Descalzo KPA, Macalalad EP. Assessment of Accuracy of COSMIC and KOMPSAT GNSS Radio Occultation Temperature and Pressure Measurements over the Philippines. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(11):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111285

Chicago/Turabian StyleDescalzo, Karl Philippe A., and Ernest P. Macalalad. 2025. "Assessment of Accuracy of COSMIC and KOMPSAT GNSS Radio Occultation Temperature and Pressure Measurements over the Philippines" Atmosphere 16, no. 11: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111285

APA StyleDescalzo, K. P. A., & Macalalad, E. P. (2025). Assessment of Accuracy of COSMIC and KOMPSAT GNSS Radio Occultation Temperature and Pressure Measurements over the Philippines. Atmosphere, 16(11), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111285