Abstract

Understanding how the path of streamers is influenced by background electric fields is crucial in leader progression models and electrical breakdown models in long gaps. While numerous advanced models of streamers exist, applying them to leader progression models to track streamer movement remains computationally intensive and impractical. In this study, we employ one of the simplest streamer models available in the literature to investigate how streamers are deflected in the presence of background electric fields. Our analysis identifies the key parameters that govern this interaction. Additionally, we estimate the time and length scales over which streamers are diverted by a background electric field of a specified strength.

1. Introduction

The process leading to electrical discharges in air involves several complex events. When an electric field is applied, electrons begin gaining energy from the field. Once the background electric field exceeds a certain critical value, the energy gained by the electrons becomes large enough to ionize other molecules. This initiates a cascade of newly created electrons, known as an electron avalanche. As the avalanche grows, the space charge accumulated at its head modifies the electric field. This modification leads to the formation of another self-propagating discharge called the streamer discharge.

Streamers are characterized by a concentration of charge at the head, which generates a large electric field at the tip. Due to this electric field, streamers continue to propagate in air even at electric field strengths lower than the critical threshold required for electron avalanche formation. As the streamer propagates, it thermally ionizes its stem, creating a conductive channel known as a leader discharge. A leader can travel in air under electric fields even lower than those required for streamer propagation. However, the strong electric field at the tip of the leader produces streamer bursts that extend the leader channel by thermalizing new sections of the leader. The direction of propagation of the leader is somewhat controlled by the direction of the streamer propagation.

Several recent studies have assumed that streamers follow the background electric field [1,2,3]. However, the validity of this assumption and the electric fields required to divert the path of a streamer are still under investigation.

In this paper, we address these questions using a simple model for the streamer. While the model may not provide exact numerical values, it correctly identifies the parameters that control the streamer and offers a qualitative understanding of how the electric field influences the propagation of the streamer, as well as how quickly the streamer can respond to changes in the background electric field. Despite its simplicity, this model identifies the factors that influence the deflection of streamer channels in background electric fields.

2. Streamer Model

Streamer models typically involve solving a set of differential equations that describe the dynamics of electrons, positive ions, negative ions, and other chemical species, along with the corresponding source and sink terms, such as collisional ionization and photon-induced ionization. These equations are coupled with the Poisson equation, which accounts for both external and internal electric fields. Early models for describing streamers were developed by Dawson and Winn [4] and by Gallimberti [5]. Since then, streamer models have evolved to solve Drift-Diffusion-Reaction (DDR) equations for charged particles in 1D, alongside the Poisson equation in a 2D axisymmetric domain [6,7]. These models, often referred to as 1.5D models, have led to more realistic streamer simulations.

For even more accurate simulations, 2D and 3D fluid, particle, and hybrid models using methods such as the Finite Element Method (FEM), Finite Volume Method (FVM), and Particle-In-Cell (PIC) methods have been developed [8,9,10]. These higher-dimensional models overcome some of the self-inconsistencies present in 1.5D models. However, they require significantly more computational resources.

In this paper, we use a simplified model of the streamer, as proposed by Winn and Dawson [4]. The rationale for selecting a simplified model of the streamer in the analysis is as follows: As mentioned earlier, the goal of the model is to understand how the path of the streamer is influenced by the background electric field. A more advanced streamer model needs to conduct the analysis in three dimensions, which becomes a challenging task when utilizing such a model. Moreover, more advanced streamer models contain more input parameters and this makes it difficult to identify the basic streamer parameters that influence its propagation in a background electric field.

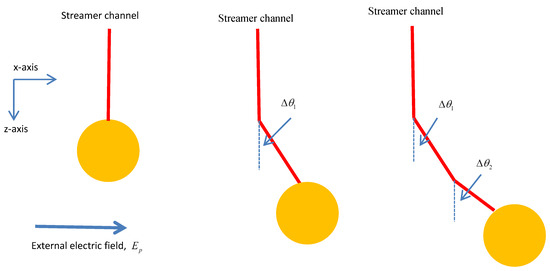

In the simplified streamer model developed by Dawson and Winn [4], the streamer discharge is treated as a positive charge blob with a well-defined radius at any given time. The region behind the streamer head is assumed to be nearly neutral, with equal amounts of positive and negative charge. The space charge blob generates a strong electric field at the head, which causes electrons ahead of the blob to initiate an avalanche toward it. As the avalanche reaches the streamer’s head, the negative charge neutralizes the streamer’s charge, creating an identical space charge blob ahead of the previous one. In this manner, the streamer advances in discrete steps. In the analysis, we assume that the avalanche reaches the head of the streamer from a direction along the maximum electric field in the space directly in front of the streamer head. Figure 1 illustrates this simple model, which was further developed by Gallimberti [5] into a more complex and detailed version of the streamer channel.

Figure 1.

The Dawson-Winn streamer model where the streamer is represented by a spherical charge connected to the high-voltage electrode with a thin channel. The secondary avalanches that neutralize the existing streamer head arrive towards it along the maximum electric field. The direction of maximum electric field is the sum of the electric field produced by the charge on the streamer head and the applied electric field.

3. Modeling the Deflection of the Streamer Channel in a Background Electric Field

Consider a streamer channel propagating along the z-axis. The combined effect of the charges located on the streamer generates an electric field, the maximum of which is also directed along the z-axis. Let the radius of the streamer head be , and the total charge in the streamer head be Q. The radius of the streamer channel head is governed by the radial diffusion of concentrated charges. As the charge density increases, the diffusion rate also increases, leading to a larger diffusion radius.

Suppose that, at a certain instant of time, an electric field is applied perpendicular to the direction of propagation of the streamer, i.e., the direction of the applied electric field is along the x-axis. Let the maximum electric field at the tip of the streamer before the application of the background field be . This electric field is given by

We assume that the streamer will maintain this self-generated electric field as it propagates. Let the speed of the streamer be . Let us denote the electric field applied perpendicular to the propagation of the streamer by Due to the applied electric field, the equivalent or effective electron avalanche generated ahead of the streamer head will approach the streamer channel at an angle given by (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Geometric definition of angles used in Equation (3) and subsequent expressions.

Since the applied electric field is much smaller than the streamer’s field (which is in the order of 107 V/m), we can approximate:

After the first avalanche, the streamer’s head will be slightly turned towards the applied electric field by this angle. In the next avalanche, the streamer will be turned towards the direction of the electric field by a similar angle, so in the second avalanche, the deflection of the streamer can be expressed as:

So in the nth avalanche, the amount of rotation of the streamer head is given by

This can be written as

In the above equation, is the angle between the z-axis (original direction of motion of the streamer) and the current direction of motion of the streamer. Observe that in deriving the above equation, we assume that the streamer head maintains the magnitude of the electric field as it deflects. Note also that at any given stage, the amount of deflection of the streamer channel is determined by the applied electric field , the charge at the head of the streamer head , the radius of the streamer channel , and the angle between the current direction of propagation of the streamer and the applied electric field. The equation shows that the larger the streamer head charge and the smaller the streamer radius, the larger the resistance to the turning motion of the streamer. It is important to point out that at each avalanche stage, the time necessary for the deflection of the streamer channel is , where is the speed of the streamer. Thus, the rate at which the streamer deflects at any given avalanche stage is controlled by the following equation:

This can be written as

Now, the speed of the streamer at any given time towards the direction of the applied field is

Note that the applied electric field is directed along the x-axis, and is the unit vector directed along the x-axis. Thus the rate of change of the speed of the streamer towards the applied electric field is given by

Substituting for from (8), we can write this equation as

This equation has the form of Newton’s law of motion, with the parameter inside the square bracket representing the ‘mass’ of the streamer, resisting its movement. This demonstrates that the resistance to the streamer’s turning motion increases with a larger streamer head charge and smaller streamer radius.

4. Results

For a given applied electric field perpendicular to the streamer channel, we can use the above equations to estimate how the streamer will deflect in space and time for different values of the electric field. For the calculations, we assume a typical streamer radius of 50 μm, a speed of 2.0 × 105 m/s and a charge of 108 ions at the head. However, results for other parameter values will also be presented.

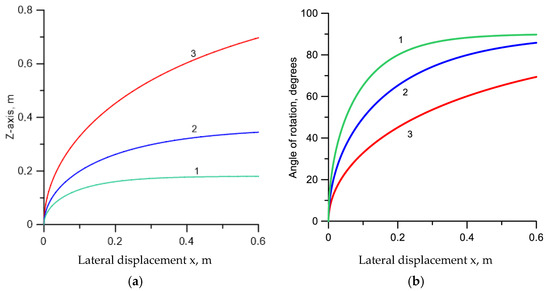

Figure 3a,b provides information concerning the lateral deflection of the streamer in the presence of an applied electric field. Before the application of the electric field, the streamer is moving along the z-axis. After the application of the electric field directed along the x-axis, the streamer head starts moving towards the x-axis. Figure 3a depicts the spatial movement of the streamer head in the z-x plane. Results are shown for three background electric fields. Figure 3b depicts how the angle between the direction of propagation of the streamer and the z-axis varies as a function of the distance traveled by the streamer along the x-axis. From the results, one can see that the distance that the streamer needs to travel before it deflects completely towards the applied field increases with decreasing applied electric field. For an applied electric field of 5 × 104 V/m, the streamer deflects towards the direction of the applied field over a distance of about 20 cm. This distance increases to over 60 cm for an applied field of 1.0 × 104 V/m.

Figure 3.

(a) Lateral deflection of the streamer head in the presence of an applied electric field. In the absence of an applied electric field the streamer moves along the z-axis. After the application of the electric field directed along the x-axis, the streamer starts moving towards the x-axis. The figure illustrates this movement of the streamer head for three different strengths of the applied electric field. (1) 5.0 × 104 V/m. (2) 2.5 × 104 V/m. (3) 1.0 × 104 V/m. (b) The angle of rotation of the streamer channel as it moves towards the direction of the applied electric field for the same three applied electric fields.

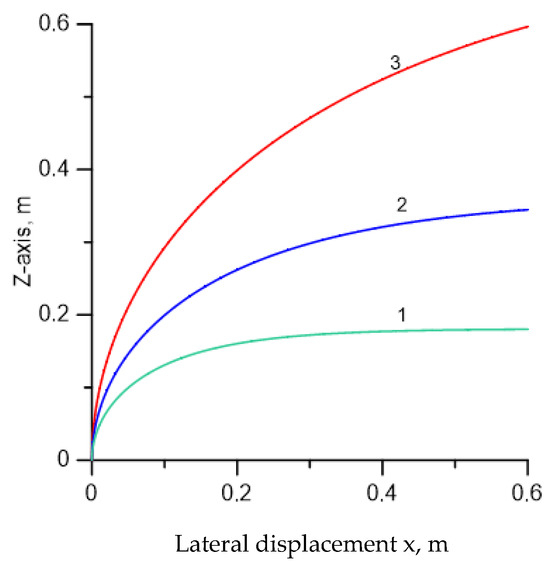

Figure 4 illustrates the deflection behavior of the streamer head in an applied electric field and how this motion is affected by the radius of the streamer. A streamer with a larger radius requires only a short distance to deflect, while a streamer with a small radius resists deflection more. This can be seen directly from Equation (11).

Figure 4.

Similar to Figure 3 except that the effect of the streamer radius is illustrated. The applied electric field is 2.5 × 104 V/m and remains the same in each case. (1) 100 μm radius. (2) 50 μm radius. (3) 25 μm radius.

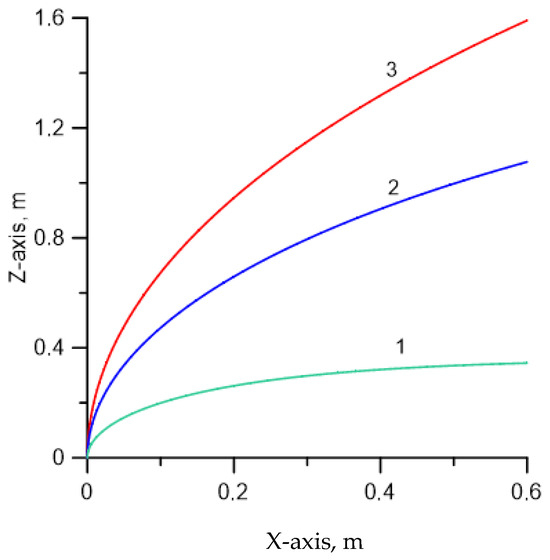

According to Equation (11), another parameter that resists the deflection movement of the streamer is the magnitude of the charge at its head. The larger the charge, the more difficult for the streamer to deflect in an applied electric field. This behavior is illustrated in Figure 5 where the deflection movement is depicted for three different values for the number of elementary charges at the streamer’s head. Observe how a larger charge increases the streamer’s resistance to deflection.

Figure 5.

Similar to Figure 3 except that the effect of the number of positive ions at the streamer’s head is illustrated. The applied electric field and the streamer radius remain the same in each case: 2.5 × 104 V/m and 50 μm. (1) 108 ions, (2) 5 × 108 ions (3) 109 ions.

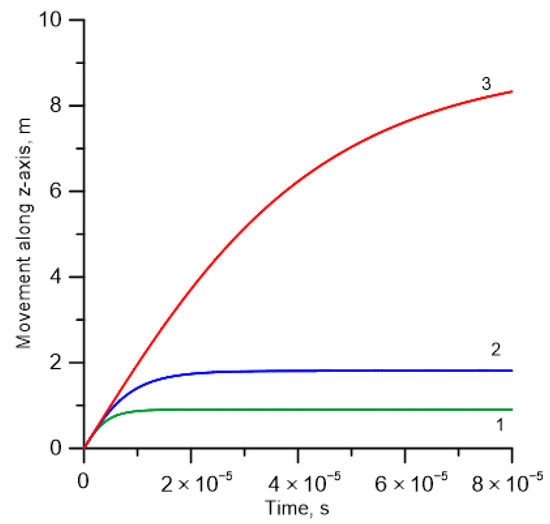

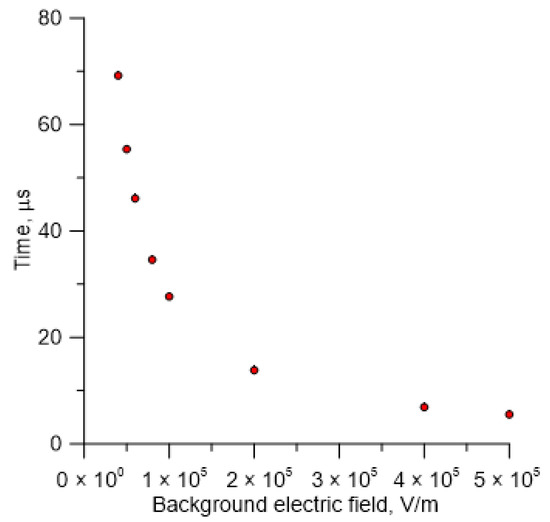

Another important question that requires an answer is the following: How fast does a streamer deflects towards an applied electric field? Of course, the answer to this question depends on the magnitude of the applied electric field. Figure 6 depicts the movement of the streamer along the z-axis after the application of the electric field. As one can understand, once the electric field is applied, the streamer starts deflecting towards the direction of the applied electric field. Figure 6 shows how fast this deflection takes place for electric fields of three different magnitudes. Note that, if the applied electric field is on the order of 10.0 × 104 V/m, the streamer deflects towards the applied electric field in a time interval of 5 to 10 μs. If the electric field is two times smaller, it will take about 10–20 μs for the streamer to deflect completely towards the direction of the applied electric field. If the electric field is ten times smaller, the time required for the streamer to deflect is more than about 80 μs. Since this information is relevant to leader progression models, Figure 7 shows the time at which the streamer has rotated 80 degrees toward the applied electric field, plotted as a function of the background field strength.

Figure 6.

The slowing of the movement along the z-axis, due to the deflection of the streamer towards the x-axis, as a function of time, for three different values of the applied electric field. (1) 10.0 × 104 V/m. (2) 5.0 × 104 V/m. (3) 1.0 × 104 V/m.

Figure 7.

The time necessary to turn the streamer by 80 degrees towards the applied electric field as a function of the applied field strength.

5. Discussion

It is important to recognize that the model used in this study is highly simplified, which means that the results offer only a qualitative understanding of how a streamer interacts with an applied electric field. In the present formulation, the streamer velocity appears independent of any sustaining applied electric field. This feature arises directly from the simplified representation of the streamer as a concentrated charge region, following the classical Dawson and Winn model. In this model, the electric field responsible for the streamer’s motion is generated primarily by the charge concentrated at the streamer head. Taken literally, this formulation implies that the streamer could continue propagating indefinitely, even in the absence of an applied electric field.

Dawson and Winn [4] were themselves aware of this limitation. In their refinements, they introduced a reduction in the streamer head charge as the streamer propagates, which effectively limits the propagation distance and prevents unphysical, infinite motion. This modification accounts for charge redistribution, energy loss, and decreasing field enhancement as the streamer extends.

It is important to note that a purely spherical charge distribution would generate an electric field that is uniformly distributed in the radial direction. However, in our analysis, we assume that the electric field associated with the spherical charge is directed along the direction of streamer propagation. This assumption is valid only if the total electric field includes not only the contribution from the spherical charge at the streamer head but also the field induced by the charge distributed along the streamer channel—particularly in the region near the head. In other words, our approach implicitly accounts for the influence of the charge located on the streamer channel. In the present work, we adopt the basic framework of the Dawson and Winn model not to describe the complete dynamics of streamer inception and propagation, but to investigate how a pre-existing, propagating streamer would deviate under the influence of an applied electric field. In other words, the present analysis assumes that the streamer already exists and is moving with a characteristic velocity determined by the inception field (not explicitly modeled here). The purpose is to isolate and study the effect of an external transverse field on its trajectory.

Because of this focus, the inherent limitation of the Dawson and Winn model—neglecting the diminishing head charge and field—does not significantly affect the conclusions of this work. The model serves as a first-order approximation to capture the essential electrodynamic interaction between the streamer’s self-field and an imposed applied field. Future refinements could incorporate charge attenuation or explicit coupling to the applied electric field to extend the model’s physical realism.

In the present model, we consider two electric field components: (i) the field generated by the space charge at the streamer head, and (ii) an externally applied field responsible for diverting the streamer from its original propagation direction. In reality, streamer inception and early propagation occur in the presence of an inception field, which is typically directed along the initial axis of streamer growth. This inception field is not explicitly included in the current formulation. However, its omission does not limit the validity of the analysis presented here. The reason is that the inception field can be regarded as one component of the total applied field acting on the streamer. In this study, we isolate and analyze the effect of a transverse (perpendicular) electric field in order to investigate, in the simplest possible configuration, how such a field modifies the streamer trajectory. If we were to include an additional field component aligned with the original propagation direction (i.e., the inception field), the resulting total electric field would simply be the vector sum of the two fields. This would not alter the qualitative behavior of the model; rather, it would reduce the apparent divergence angle of the streamer, since the longitudinal field component would dominate the motion along the primary axis. In principle, the same analytical framework can accommodate an applied electric field of arbitrary orientation with respect to the initial propagation direction. The present choice of a perpendicular configuration serves as a limiting case that allows a clear interpretation of the influence of transverse electric fields on streamer motion. Future extensions of the model could explicitly include both longitudinal and transverse components of the applied field to represent more realistic discharge environments.

In our analysis, we assume that electron avalanches propagate along the direction of the maximum electric field, which results from the superposition of the streamer head field and the applied external field. This assumption defines the deterministic trajectory of the streamer in the model. However, in reality, the initiation of avalanches depends on the random appearance of free electrons, which are generated primarily by photoionization and, to a lesser extent, by the detachment of negative ions. These processes are inherently stochastic, meaning that seed electrons can appear at various locations around the streamer head, not exclusively along the direction of the maximum field. Consequently, individual avalanches may develop in directions slightly deviating from the predicted maximum-field line. In this sense, the model should be interpreted as describing the most probable direction of streamer propagation rather than an exact deterministic path. The actual motion of the streamer head between successive steps would statistically fluctuate around this mean trajectory, depending on the local availability and spatial distribution of seed electrons. While these stochastic effects are not explicitly included in the present simplified model, their influence can be qualitatively understood as introducing small random deviations around the calculated trajectory. Incorporating such effects would require a probabilistic or Monte Carlo-type approach to simulate the statistical distribution of avalanche initiation sites, which is beyond the scope of the current analytical treatment but would be an important direction for future development.

In the present analysis, the formation of streamer branches has not been explicitly considered. In reality, the stochastic nature of avalanche initiation—driven by random variations in local ionization and seed electron availability—can lead to the development of multiple regions of enhanced space charge near the streamer head. When two or more such regions form simultaneously, they can evolve into separate streamer heads, resulting in branching [3,11,12]. Although branching is neglected in the current model for the sake of analytical simplicity, the theoretical framework developed here remains applicable to each branch individually once it has formed. In principle, the same analysis can be extended to describe the subsequent propagation and divergence of multiple streamer heads under the influence of local and applied electric fields. A more complete treatment of branching would require a probabilistic or spatially resolved model that accounts for local field enhancement, space charge interaction between branches, and stochastic photoionization effects. These aspects are beyond the scope of the present study but are currently under consideration for future work.

As stated earlier, the central concept developed in this paper is that a streamer propagates along the direction of the maximum electric field, which results from the superposition of the electric field at the streamer head and all externally applied fields in the system. This assumption provides a simple, yet physically meaningful way to describe streamer divergence. Laboratory experiments with high-voltage electrodes have shown that positive and negative streamers follow the curvature of the applied electric field, demonstrating that their trajectories are guided by the resulting field distribution. A comparison between this model’s assumption, namely that the streamers tend to propagate along electric field lines, and available experimental data was previously carried out by the present authors [3], demonstrating that the observed streamer trajectories [13] are consistent with propagation along the direction of maximum field intensity. The results presented here further substantiate that interpretation by providing a theoretical justification for this assumption. In addition, several theoretical and computational models of lightning leader propagation models explicitly assume that streamers advance along the direction of maximum local electric field [14,15], which is consistent with the results presented here. This combination of empirical and modeling evidence supports the fundamental assumption in the present analysis that the streamer’s motion is aligned with the electric field lines generated by the applied high-voltage configuration.

Since our analysis is based on positive streamers, the study provides preliminary data essential for understanding the movement of positive lightning leaders (both upward and downward). Lightning leaders, both positive and negative, advance with the assistance of streamer bursts that travel ahead of the leader’s tip, and the direction of propagation is determined by the movement of these streamer bursts. The regions through which the leaders travel contain various sources of electric fields, such as space charge pockets, charges induced on grounded objects, and charges present on connecting leaders. One key question in leader propagation models is the magnitude of the applied electric field required to alter the direction of the streamers associated with the leader, and consequently, the leader’s path. The results presented in this paper offer initial insights into this question. The procedure outlined here can also be extended, with appropriate modifications, to study the diversion of negative streamers in electric fields; the calculation procedure outlined here can be readily integrated into the numerical routines used in leader progression studies and their applications [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

The behavior of streamers in an electric field is also crucial in laboratory studies related to the electrical breakdown of discharge gaps [22,23]. This is particularly significant in multi-gap discharges, where different electrodes compete to attract the streamer discharges. Many such studies assume that streamers follow the applied electric field, based on the premise that streamers respond rapidly to changes in the field. However, as the results presented in this paper demonstrate, the validity of this assumption depends on the strength of the applied electric field. Specifically, within the region of interest for electrical breakdown, streamers may only follow the applied electric field when its magnitude exceeds a certain threshold.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we applied the simplified model developed by Dawson and Winn to explore the effects of lateral electric fields on the deflection of streamer channels. The results reveal that, depending on the strength of the applied electric field, a typical streamer can fully curve toward the field direction within a timespan ranging from microseconds to tens of microseconds, and over spatial distances ranging from tens of centimeters to hundreds of centimeters. These findings offer valuable insights for leader progression models and electrical breakdown models of long gaps.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C. and G.C.; Methodology, V.C. and G.C.; Formal analysis, V.C., G.C., H.J., F.R. and M.R.; Writing—original draft, V.C., G.C. and H.J.; Writing—review & editing, V.C., G.C., H.J., F.R. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cooray, V.; Arevalo, L. Modeling the Stepping Process of Negative Lightning Stepped Leaders. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, V. Origin of the Fine Scale Tortuosity in Sparks and Lightning Channels. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, V.; Jayasinghe, H.; Rubinstein, M.; Rachidi, F. The Geometry and Charge of the Streamer Bursts Generated by Lightning Rods under the Influence of High Electric Fields. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.A.; Winn, W.P. A model for streamer propagation. Z. Für Phys. 1965, 183, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallimberti, I. A computer model for streamer propagation. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1972, 5, 2179–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, R.; Lowke, J.J. Streamer propagation in air. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1997, 30, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.; Zeng, R. A local discontinuous galerkin method for 1.5-dimensional streamer discharge simulations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 219, 9925–9934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Teunissen, J.; Ebert, U.; Becker, M.M.; Chen, S.; Ducasse, O.; Eichwald, O.; Loffhagen, D.; Luque, A.; Mihailova, D.; et al. Comparison of six simulation codes for positive streamers in air. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27, 095002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, J.; Ebert, U. Simulating streamer discharges in 3d with the parallel adaptive afivo framework. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 474001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, A.; Teunissen, J. A comparison of particle and fluid models for positive streamer discharges in air. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2022, 31, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatov, N.A.; Kostinskiy, A.Y.; Syssoev, V.S.; Andreev, M.G.; Bulatov, M.U.; Sukharevsky, D.I.; Mareev, E.A.; Rakov, V.A. Experimental investigation of the streamer zone of long-spark positive leader using high-speed photography and microwave probing. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 123, e2019JD031826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Jin, H.; Peng, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Luo, B.; Dong, X. Study on the tortuosity of long air gap discharge channels at an altitude of 4650 m in China. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Li, Z.; Pei, X.; Zhao, X.; Lu, G.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Dong, X. Effects of applied voltage on branching of positive leaders in laboratory long sparks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellera, L.; Garbagnati, E. Lightning strike simulation by means of the Leader Progression Model: II. Exposure and shielding failure evaluation of overhead lines with assessment of application graphs. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1990, 5, 2023–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, V.; Ruhnke, L.H. Determining the striking distance of lightning through its relationship to leader potential. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H.R.; Whitehead, E.R. Field and analytical studies of transmission line shielding. IEEE Trans. 1968, 87, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, F. A model for switching impulse leader inception and breakdown of long air-gaps. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1989, 4, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.J. An improved electrogeometric model for transmission line shielding analysis. IEEE Trans. 1987, 2, 871–877. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra, M.; Cooray, V. A self-consistent upward leader propagation model. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006, 39, 3708–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Torres, H. On the development of a lightning leader model for tortuous or branched channels—Part I: Model description. J. Electrost. 2008, 66, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.; Torres, H. On the development of a lightning leader model for tortuous or branched channels—Part II: Model results. J. Electrost. 2008, 66, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallimberti, I. The mechanism of the long spark formation. J. De Phys. Colloq. 1979, 40, C7-193–C7-250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les Renardiéres Group. Research on long air gap discharges—1973 results. Electra 1974, 35, 47–155. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).