1. Introduction

The gravitational and centrifugal forces of the Earth–Moon system induce a westward propagating lunar semidiurnal tide M

2 with a period of 12.4206 h and a zonal wavenumber 2 in the Earth’s ocean and atmosphere. The lunar atmospheric tide is maximal at low latitudes where the small surface air pressure variation has amplitudes from 5 to 10 Pa [

1,

2,

3]. While lunar tidal winds are about 0.03 m/s at the Earth’s surface, they increase to amplitudes of 10 m/s or more in the ionospheric E region [

1,

4,

5,

6]. During sudden stratospheric warmings (SSWs), the lunar tide is amplified, and wind amplitudes of 40 to 50 m/s can occur in the dynamo region [

6]. The ionospheric effects of the lunar tide are most obvious in the equatorial ionosphere [

7,

8]. Generally, lunar tides should be taken into account in space weather models [

6,

9]. The electric field variations induced by the M

2 tide in the E region (100 to 110 km altitude) are projected along the geomagnetic field lines from the E region into the F region. The

plasma drift causes an electrodynamic lifting of the F region plasma at low magnetic latitudes leading to a periodic variation in the equatorial ionization anomaly (EIA) [

6,

10]. It was observed that parameters of the EIA crest in TEC are periodically influenced by the Moon phase with a period of 14.77 days. This is due to the beat of the solar and lunar semidiurnal tides in the ionosphere [

11]. The eccentricity of the Moon orbit causes an additional modulation of the lunar tide in TEC with the period of the anomalistic month (27.55455 days, which is the average time between two perigee transits of the Moon) [

12]. The equilibrium theory of tides shows that the lunar tide at apogee is smaller than the lunar tide at perigee.

The term “big L days” was first reported by Bartels and Johnston in 1940 [

13], who analyzed ground-based magnetic observations (horizontal intensity of geomagnetic field) at Huancayo in Peru. On big L days, the lunar influence in the ionospheric equatorial electrojet was considerably large and even comparable to the solar effects. The research works on the possible causes of the big L days in ground-based magnetometer data have been summarized by Siddiqui et al. [

14]. Generally, longitudinal and latitudinal dependences of the effects of big L days in ground-based magnetic observations are present, which can be due to both geographical variations in the vertical atmosphere profiles (affecting the upward propagation of the lunar tide) and horizontal gradients of electric conductivity in the lower ionosphere. Pekeris [

15] explained that the atmosphere is resonant for the solar semidiurnal tide where the strength of the resonance effect depends on the vertical profile of temperature. Following this resonance theory of Pekeris, Forbes and Zhang [

5] investigated the influence of the SSW of January 2009 on the lunar tide. They found that the resonance period of the atmosphere shifts to the period of the lunar semidiurnal tide, when a sudden stratospheric warming occurs. Thus, a SSW is able to amplify the lunar tide by a factor of 3 to 6, which was observed and simulated in case of the SSW of January 2009 [

5]. The amplification of the lunar tide by SSWs explains the reported correlation of big L days with the occurrence of SSWs [

14]. Both big L days and SSWs mostly happen during Northern hemispheric winter [

14]. The modification of the lunar semidiurnal tide by SSWs was firstly simulated by [

16], who found that a SSW changes the phase of the lunar tide. This simulation result agreed with radar observations of the lunar tide in the mesosphere.

While there are many studies about big L days in ground-based magnetic data, there are no studies about big L days in TEC data yet. Big L days in TEC are different from big L days in ground-based magnetic data since the excitation process of the lunar variation in TEC involves the electrodynamic lifting of the F region plasma of the EIA. The present study is an initial study which gives a first impression on big L days in GNSS TEC. An investigation of the relationship between big L days in magnetometer data and big L days in GNSS TEC data is certainly an interesting topic for a future study but is not investigated in the following. The long-term data set of world maps of GNSS TEC, established since 1998 and provided by the IGS, is a unique opportunity to study the characteristics of big L days in TEC. It was already found that the semidiurnal tide in TEC is enhanced after SSW events [

17,

18]; however, a separation between the lunar and solar tidal variation in TEC was not performed. Here, we focus on the lunar M

2 variation in TEC. An open question also concerns whether there are other reasons for big L days than the occurence of SSWs.

Section 2 describes the TEC dataset and the time series analysis. The results are shown in

Section 3, while

Section 4 contains the discussion and conclusions.

3. Results

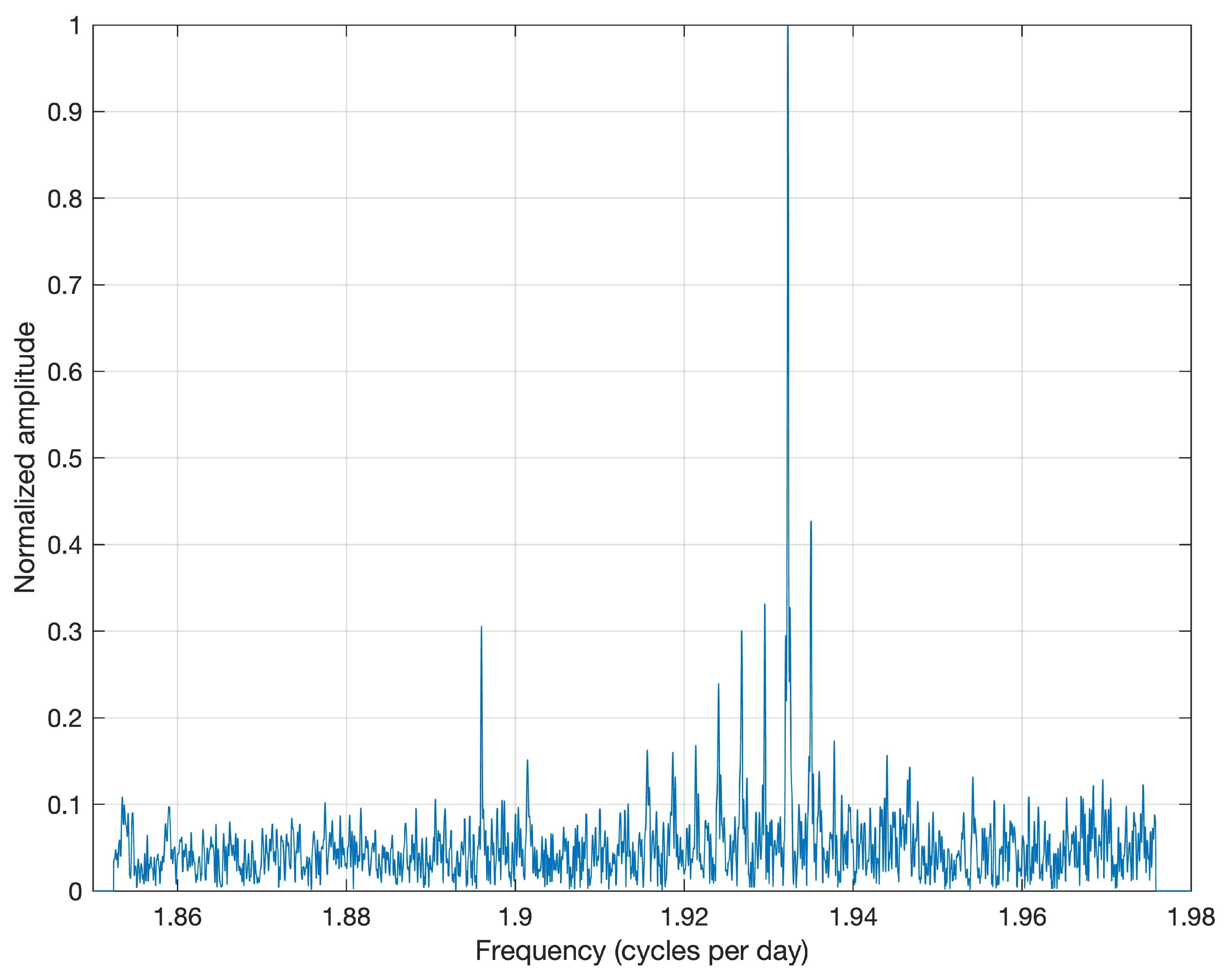

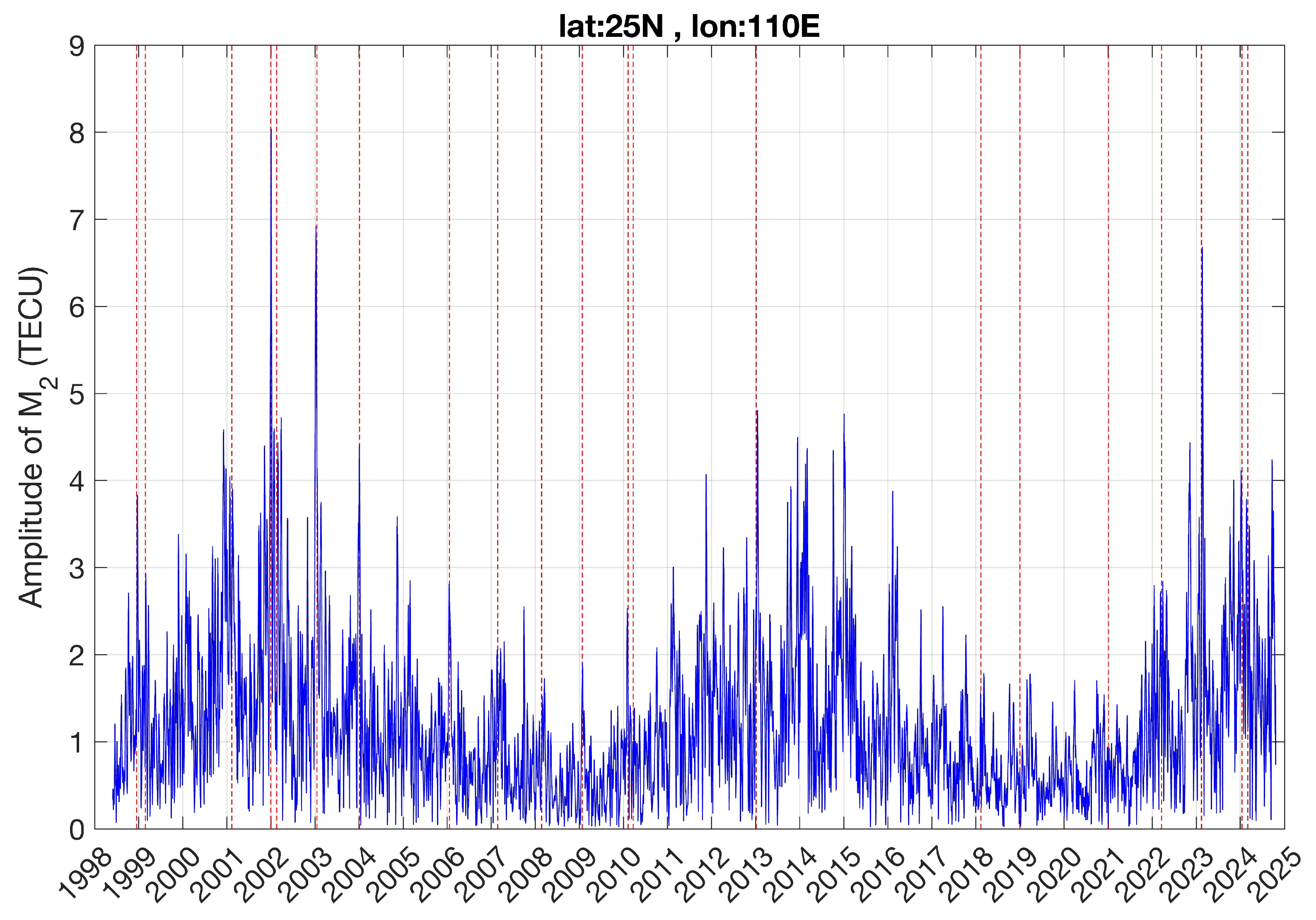

The derived time series of the M

2 amplitude in TEC in Southern China (25° N, 110° E) is depicted in

Figure 2. It can be seen that the M

2 amplitude increases during solar maximum and also in northern hemispheric winter. There are some spikes which we like to call big L days. These big L days often occur shortly after SSW events, which are indicated by the vertical red dashed lines in

Figure 2. The maximal M

2 amplitude is about 8 TECU and it is reached on 2 January 2002, three days after the SSW of 30 December 2001. The absolute amplitude might be not a necessary criterium for a big L day. For example, there is a small M

2 peak just after the SSW of 24 January 2009. We would also consider this peak a big L day. Indeed, the amplification of the M

2 tide after the SSW of 2009 was the subject of the studies by [

5,

6]. Thus, we suggest that every M

2 peak which is larger by a factor of 2 or more than its vicinity (e.g., monthly mean) might be considered as a big L day.

Figure 2 shows that some big L days are not accompanied by SSW events. Thus, an amplification of M

2 in TEC might be possible due to atmospheric and ionospheric processes other than SSW.

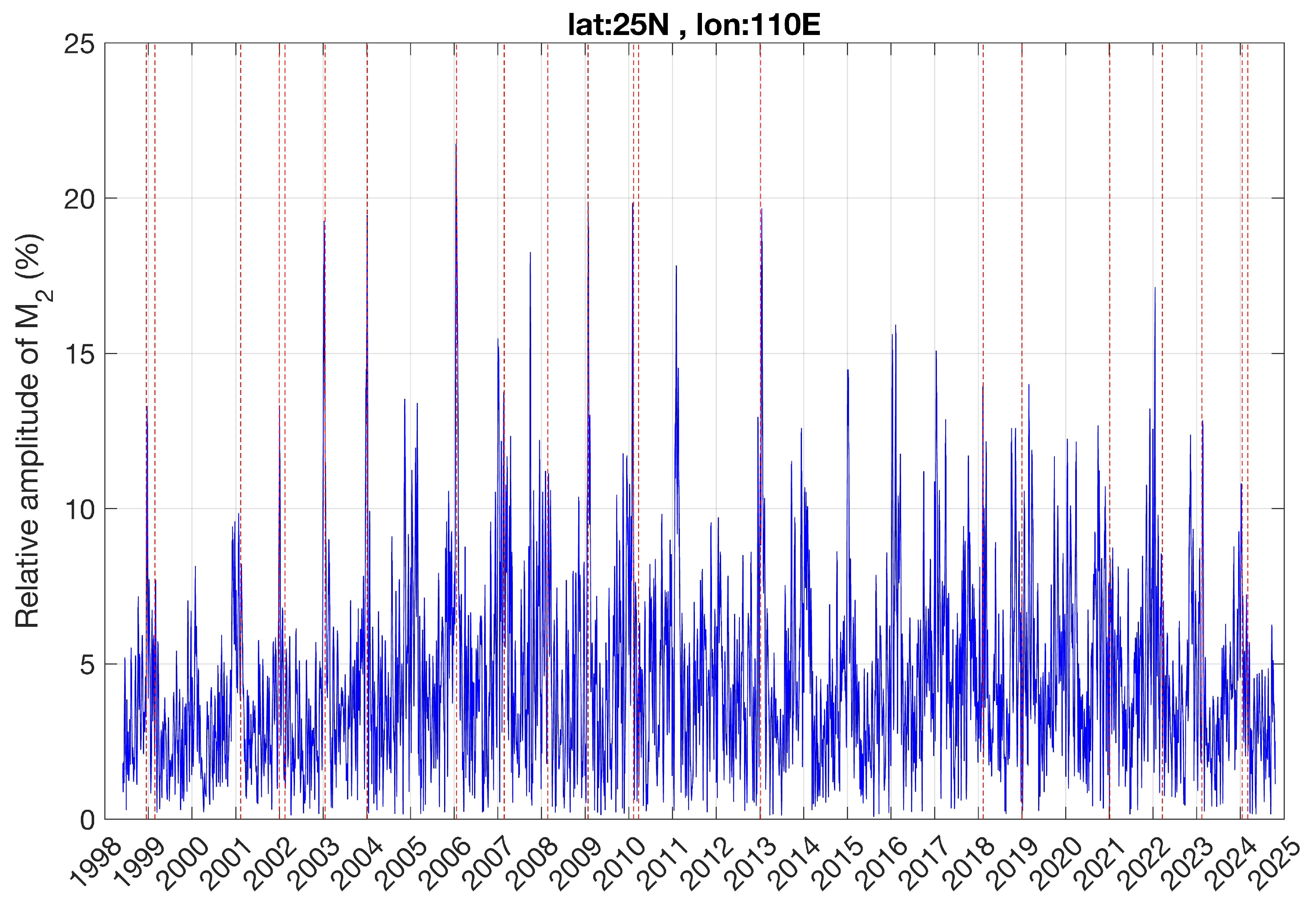

Past studies of lunar tides often discussed the relative amplitude of M

2 in TEC, where the relative variation was calculated with respect to a daily zonal mean or a monthly climatological mean [

5,

25,

26].

Figure 3 shows the relative M

2 amplitude in percent (with respect to the monthly mean of TEC) in Southern China (25° N, 110° E). The series of the monthly mean was determined by means of a 30-day low pass filter, which was applied to the TEC series at the selected location. The relative amplitude reaches amplitudes of about 20%, for example, at the SSWs of 2006 and 2009. The mean relative amplitude from 1994 to 2024 was 4.5%. This value is comparable with the relative M

2 amplitudes of 6 to 7%, as reported by [

26] for Brazil and by [

25] for the EIA region.

Figure 3 shows that the relative M

2 variation increases from about 4.5% to about 20% for several SSW events. This agrees with the amplification factor of 3 to 6 for the M

2 tide, which was found for the major SSW of 2009 by [

5] when analyzing CHAMP satellite observations and Global Scale Wave Model (GSWM) simulations of the thermosphere and ionosphere.

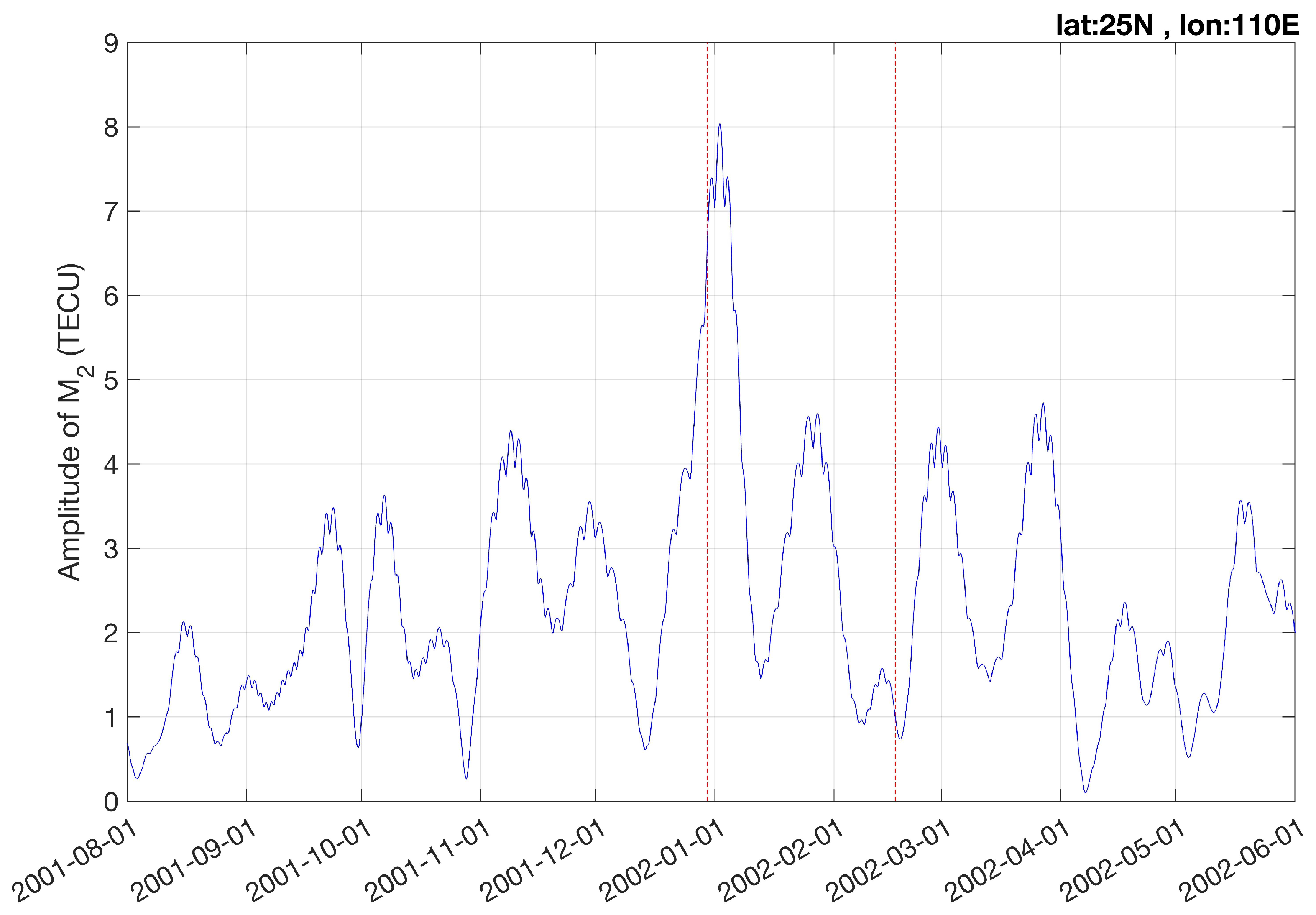

Figure 4 depicts a zoom of the M

2 amplitude in northern hemispheric winter 2001/2002. It is obvious that the M

2 peak just occurs after the SSW event of 30 December 2001. However, there is no clear M

2 peak related to the other SSW on 17 February 2002. So, an SSW can happen without an obvious effect on the M

2 amplitude.

Figure 4 also shows that the time resolution of the M

2 amplitude series is about 10 days. There are some small fluctuations with periods less than 10 days; however, this is just noise due to imperfect amplitude determination or small retrieval errors. The separation of the S

2 variation from the M

2 variation causes the limitation in the time resolution. It would be an interesting topic for future research if other data analysis methods could enhance the time resolution of the M

2 amplitude series. Chau et al. [

27] fitted sine waves of lunar and solar tides to mesospheric wind data and synthetic data. The results suggested that a data segment length of 21 days is the best choice. Shorter data window lengths of 11 and 15 days provided sometimes undesired artifacts in the retrieved parameters of the synthetic dataset.

The time series of the M

2 amplitude in TEC strongly depends on latitude and longitude. Thus, big L days can occur at one place while they do not happen at other places. As an example, we show the M

2 amplitude series in Chile (−30° N, −70° E) in

Figure 5. The maximal amplitude occurs on 12 February 2016. This big L day was not accompanied by a SSW event, and it was not obvious in the M

2 amplitude series in Southern China (

Figure 2). This example shows that the term big L day can be only used in a regional context.

Figure 6 shows the geographical distribution of the M

2 amplitude on the big L day of 2 January 2002. Large amplitudes are reached in the northern hemisphere close to the EIA. There are longitudinal variations with amplification of M

2 amplitude over Hawaii, North Africa, Arabia and Southern China. The maximum of about 8 TECU occurs in Southern China. A similar plot is shown in

Figure 7 for the big L day of 12 February 2016. Now, the maximum of the M

2 amplitude occurs above Chile where a value of 5 TECU and more is reached.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show that the geographical distribution of the M

2 amplitude can be quite different on different big L days.

It was obvious that big L days often occur after SSW events. Thus, it makes sense to compute composites of the M

2 amplitude with respect to epoch days, where epoch day 0 refers to the central date of the SSW. The composites contain the average results of the 21 major SSWs listed in

Table 1.

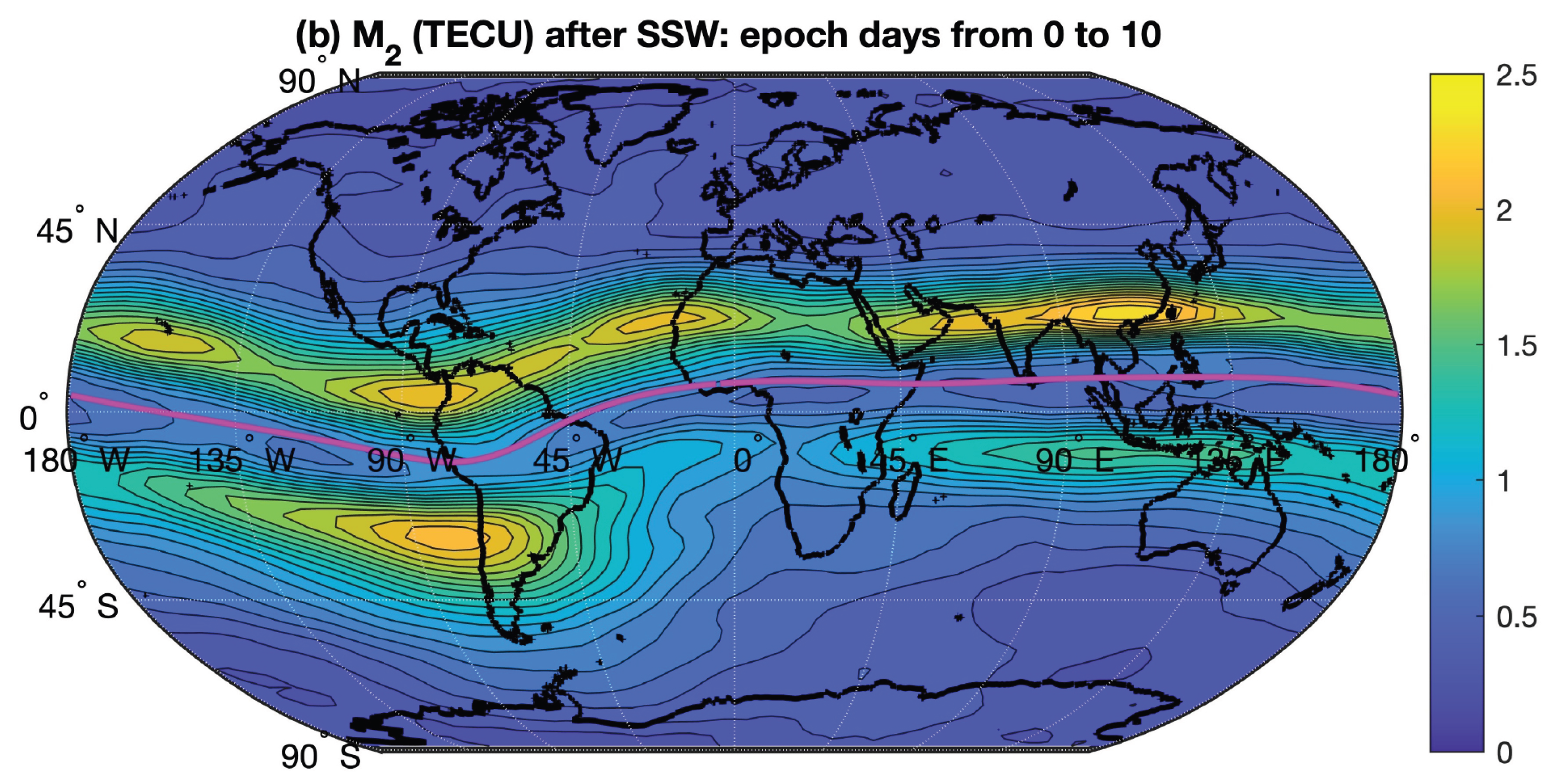

Figure 8a shows the M

2 amplitude averaged for the time interval of 20 to 10 days before the SSW event.

Figure 8b shows the M

2 amplitude averaged from epoch day 0 to 10 after the SSW. It is obvious that the M

2 amplitude is stronger after the SSW than before the SSW. Generally, the M

2 amplitude is strong along the EIA with maxima over the American longitude sector and Southern China.

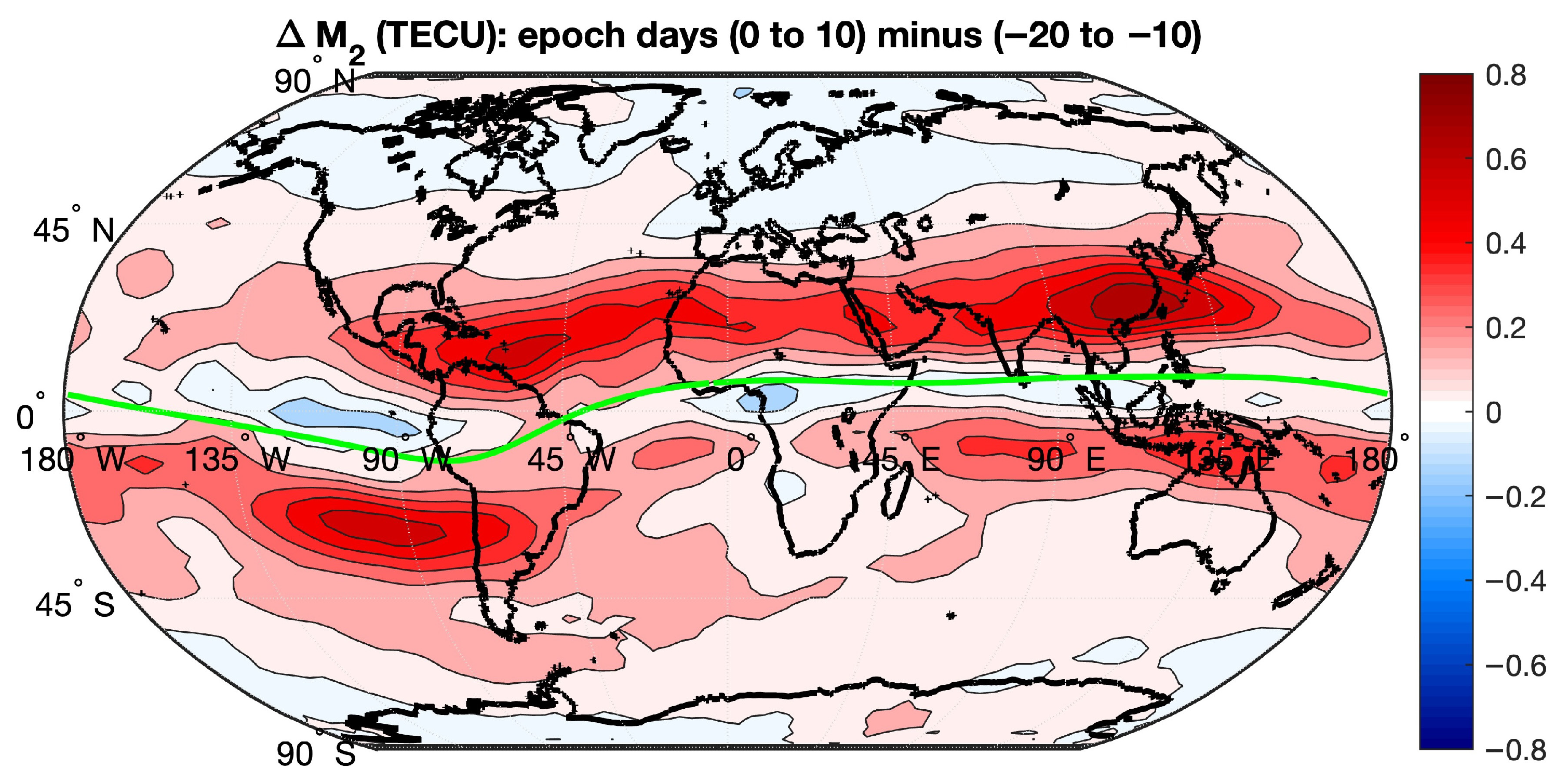

Figure 9 shows the difference of the composites before SSW (

Figure 8b minus

Figure 8a). The largest increase in the M

2 amplitude occurs after the SSW with about 0.8 TECU in Southern China.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In the past, research on big L days was restricted to the horizontal intensity of the geomagnetic field observed by ground-based magnetometers. It was supposed that the different vertical propagation conditions of the atmospheric tide M

2 and differences in the electric conductivity in the E region were responsible for the geographical distribution of the M

2 amplitude [

14]. In particular, a strong lunar M

2 variation was observed in Peru. The results of the magnetometer data cannot be directly transfered to the GNSS TEC results, since the generation of the lunar TEC variations further depend on the electrodynamic lifting processes of the equatorial ionospheric plasma and transport processes in the F region. Thus, it is worth studying the topic of big L days in GNSS TEC. Some of the obtained results are a bit similar to the results from the magnetometer data, since the electric field variations in the E region also play a crucial role in the GNSS TEC lunar variations.

The analysis of the GNSS TEC time series from 1998 to 2024 yielded the result that M

2 amplitudes of up to 8 TECU can be achieved during big L days. A higher value is likely, since the time resolution of our analysis was limited to about 10 days. However, there are other studies suggesting that a higher time resolution may cause artifacts [

27]. The amplitude values of the relative M

2 variations roughly agree with previous studies by [

5,

25,

26]. A mean value of about 4.5% was found for Southern China from 1998 to 2024. During several SSW events (e.g., SSWs of 2006 and 2009), the M

2 amplitude increased from about 4.5% to about 20%. Such an amplification of about 4 was also reported by [

5] for the SSW of 2009 and explained by means of the Pekeris resonance effect, since the resonance period of the atmosphere can shift to the period of the lunar semidiurnal tide during an SSW event.

Defining a big L day is difficult since the M

2 amplitude largely depends on the solar cycle and the seasonal cycle, with maximal values at solar maximum and northern hemispheric winter. It also makes a difference if one looks at the absolute or relative variations in the M

2 amplitude (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). It seems that the relationship between big L day and SSW event is better seen in the relative M

2 amplitude. We suggest that a sudden increase in the M

2 amplitude by a factor of 2 or more (relative to the monthly mean) at a certain location would indicate a big L day at this location. As an example, we found a big L day in Chile (12 February 2016) which was not extraordinary in Southern China. Further, there was a big L day in Southern China (2 January 2002) which was not strong in Chile.

By looking at the time series of the M

2 amplitude, it is evident that big L days often occur a few days after SSW events. It is likely that SSWs change the vertical propagation condition of the lunar tide, leading to stronger electric field variations in the dynamo region [

5,

6]. An amplification factor of 3 to 6 for the M

2 tide by an SSW, as reported by [

5], agrees with the spikes in the time series of

Figure 3 in the present study.

However, we found several SSWs which were not accompanied by big L days. Also, big L days can happen without a preceding SSW event. This indicates the existence of other reasons for big L days. In addition, the circulation changes in the middle atmosphere might be different for different SSW events, so some SSWs can amplify the lunar tide more than others. In spite of these considerations, the composite analysis of 21 major SSWs clearly shows that the M2 amplitude after the SSW event is larger than before the SSW event. We also found that the maximal SSW-induced increase in the M2 amplitude occurs in Southern China.

Generally, our study showed that big L days in GNSS TEC are an important topic. Because of the sudden amplification of the M2 amplitude by a factor of 4 or more and large absolute values of the M2 amplitude of up to 8 TECU, big L days should be considered in space weather research. The worldwide maps of GNSS TEC, available since 1998, provide excellent material for investigating the characteristics of big L days for case studies. Lunar effects are usually not included in atmospheric models. A characterization of big L days in TEC leads to progress in ionospheric research. The GNSS TEC data could help to verify the propagation of lunar tides in future space weather models. Another interesting target would be to characterize the differences and similarities of big L days in ground-based magnetometer data and TEC data.